Abstract

Background

Effects of sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on reducing hospitalization for heart failure have been reported in randomized controlled trials, but their effects on patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are unknown. This study aimed to evaluate the drug efficacy of luseogliflozin, a sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and HFpEF.

Methods and Results

We performed a multicenter, open‐label, randomized, controlled trial for comparing luseogliflozin 2.5 mg once daily with voglibose 0.2 mg 3 times daily in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus suffering from HFpEF (left ventricular ejection fraction >45% and BNP [B‐type natriuretic peptide] concentrations ≥35 pg/mL) in a 1:1 randomization fashion. The primary outcome was the difference from baseline in BNP levels after 12 weeks of treatment between the 2 drugs. A total of 173 patients with diabetes mellitus and HFpEF were included. Of these, 83 patients were assigned to receive luseogliflozin and 82 to receive voglibose. There was no significant difference in the reduction in BNP concentrations after 12 weeks from baseline between the 2 groups. The ratio of the mean BNP value at week 12 to the baseline value was 0.79 in the luseogliflozin group and 0.87 in the voglibose group (percent change, −9.0% versus −1.9%; ratio of change with luseogliflozin versus voglibose, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.78–1.10; P=0.26).

Conclusion

In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and HFpEF, there is no significant difference in the degree of reduction in BNP concentrations after 12 weeks between luseogliflozin and voglibose.

Registration

URL: https://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm; Unique identifier: UMIN000018395.

Keywords: B‐type natriuretic peptide, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor

Subject Categories: Heart Failure; Diabetes, Type 2

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BNP

B‐type natriuretic peptide

- EF

ejection fraction

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESC

European Society of Cardiology

- E/e′

ratio of early mitral inflow velocity to mitral annular early diastolic velocity

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- MUSCAT‐HF

Management of Diabetic Patients with Chronic Heart Failure and Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

- SGLT2

sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

The MUSCAT‐HF (Management of Diabetic Patients with Chronic Heart Failure and Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction) study is the first prospective, multicenter, open‐label, randomized controlled trial to investigate the drug effect of an sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, luseogliflozin, on BNP (B‐type natriuretic peptide) concentrations as the primary outcome compared with an alpha‐glucosidase inhibitor, voglibose.

We found that BNP concentrations decreased after initiation of either luseogliflozin or voglibose; however, there was no significant difference in the degree of reduction in BNP concentrations after 12 weeks for luseogliflozin and voglibose (percent change, −9.0% versus −1.9%; ratio of change with luseogliflozin versus voglibose, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.78–1.10; P=0.26).

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Our findings support no clear evidence of the effect of sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in reducing BNP concentrations at 12 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and a requirement of further investigations including ongoing larger randomized controlled trials.

For the past 2 decades, a better prognosis was able to be achieved than was previously possible in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (EF) because of the advent of guideline‐based medicine and device therapy. However, the effectiveness of these therapeutic agents has not been clarified in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in clinical trials.1, 2, 3, 4 Furthermore, recent guidelines suggest no effective medication for HFpEF.5, 6

Sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which are antidiabetic drugs for promoting urinary glucose excretion, have been suggested to reduce hospitalization for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in recent randomized controlled trials.7, 8, 9 Recently, a randomized study showed that dapagliflozin decreased worsening heart failure in patients with heart failure and a reduced EF, regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes mellitus.10 SGLT2 inhibitors are being studied in large trials for HFpEF, but no detailed data on the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in HFpEF have been obtained.

To investigate whether an SGLT2 inhibitor has preventative effects on heart failure beyond glucose‐lowering effects in patients with HFpEF, we prospectively compared luseogliflozin and alpha‐glucosidase in the MUSCAT‐HF (Management of Diabetic Patients with Chronic Heart Failure and Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction) trial. We compared the drug efficacy of luseogliflozin (an SGLT2 inhibitor) with voglibose (an alpha‐glucosidase inhibitor), which have established safety for cardiovascular events11 as control agents. BNP (B‐type natriuretic peptide) was used as the index of the therapeutic effect in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and HFpEF. This study aimed to determine the therapeutic effect of this SGLT2 inhibitor on HFpEF in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Design

Details of the study design have been published previously12 (Data S1 through S3).The MUSCAT‐HF trial was a multicenter, prospective, open‐label, randomized controlled trial for assessing the effect of luseogliflozin (2.5 mg once daily) compared with voglibose (0.2 mg 3 times daily) on left ventricular load in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and HFpEF. The change in ratio of BNP concentrations after administration of the study drug from baseline was used as a surrogate biomarker for heart failure (Figure S1 and Table S1). This study was approved by the Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Density and Pharmaceutical Sciences and the Okayama University Hospital Ethics Committee, as well as the ethics committee of each participating center. The investigation conforms with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. This trial was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN000018395).

Members of the steering committee also designed the study and are responsible for its conduction. Significant adverse events that occurred within 30 days after final administration of the study drug or after 30 days with a suspicion of association with the study drug, as well as all pregnancies, were immediately reported to the steering committee and the sponsor by the investigators, in accordance with the guidelines for good clinical practice.

Participants

Patients aged ≥20 years with requirement of additional treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus, despite ongoing treatment, and HFpEF were eligible for participation. HFpEF was defined as a left ventricular EF ≥45%, BNP concentrations ≥35 pg/mL, and any symptoms, such as shortness of breath, orthopnea, and leg edema. The criterion of BNP concentrations was based on the fact that the definition of chronic heart failure according to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines includes BNP concentrations ≥35 pg/mL.13 Patients with BNP concentrations <35 pg/mL; treatment with alpha‐glucosidase inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors, glinides, or high‐dose sulfonylurea; renal insufficiency (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2); a history of severe ketoacidosis or diabetic coma within 6 months before participation; poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus (hemoglobin A1c >9.0%); and hypertension were excluded (see full exclusion criteria in Data S1). All participants provided written informed consent before participation. Study candidates were assessed for eligibility within 4 weeks before enrollment.

Interventions and Study Procedures

Patients fulfilling all criteria who provided written informed consent to participate in this study were enrolled and subsequently randomized (1:1) to receive luseogliflozin (2.5 mg once daily) or voglibose (0.2 mg 3 times daily) in addition to their background medication. Luseogliflozin is an SGLT2 inhibitor, which has 1600‐fold selectivity of SGLT2 to SGLT1,14 and is currently approved or marketed in Japan, but not in North America and European countries. Randomization was performed using a computer‐generated random sequence web response system. Patients were stratified by age (<65 years, ≥65 years), baseline hemoglobin A1c values (<8.0%, ≥8.0%), baseline BNP concentrations (<100 pg/mL, ≥100 pg/mL), baseline renal function (eGFR ≥60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2), use of thiazolidine (yes or no), and presence or absence of atrial fibrillation and flutter at screening.

Laboratory data, ECGs, echocardiography, and patients’ vital signs, body weight, and waist circumference were evaluated at 4 and 12 weeks after initiation of study treatment. Safety and tolerability were assessed during the treatment period. After 12 weeks, expansion of follow‐up for an additional 12 weeks was continued in patients who agreed. If a patient's glycemic control worsened after 4 weeks, the investigator increased the dose of allocated treatment (luseogliflozin 5 mg once daily or voglibose 0.3 mg 3 times daily) and other specific antidiabetic drugs, except for sulfonylureas. Investigators were also encouraged to treat all other cardiovascular risk factors according to the local standard of care. Under the following circumstances, the investigators evaluated the data and patient's vital signs: (1) discontinuation of study treatment; (2) dose increase of specific treatment for heart failure; (3) initiation of new treatment for heart failure; and (4) withdrawal from the study. The permitted medications for treatment of heart failure included angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta‐blockers, diuretics, and mineralocorticoid/aldosterone receptor antagonists.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was the change in ratio of BNP concentrations after 12 weeks of treatment from baseline. The main safety outcomes were adverse events, including major adverse cardiovascular events, hypoglycemic adverse events (requiring any intervention), and urinary tract infection. Major adverse cardiovascular events included cardiovascular death, acute coronary syndrome, hospitalization for heart failure, and stroke. Details of the main safety outcomes are shown in Data S3. The main secondary outcomes of this study were the differences in the following parameters between 12 weeks and baseline: the ratio of early mitral inflow velocity to mitral annular early diastolic velocity (E/e′), left ventricular EF, body weight, and hemoglobin A1c values. Further exploratory analysis is listed in Data S1. We also conducted analyses of exploratory clinical outcomes, including changes in systolic blood pressure, heart rate, eGFR, NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐BNP) concentrations, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein concentrations, the ratio of early to atrial mitral inflow velocity, mitral annular early diastolic velocity, left atrial diameter, left atrial volume index, and left ventricular mass index.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated that the change in ratio of BNP concentrations in the luseogliflozin group would be 30% lower compared with that in the voglibose group according to previous studies of the effect of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors on heart failure.15, 16, 17 The standard deviation of the natural logarithmic transformation of BNP was estimated as 0.83 on the basis of a previous study.17 A minimum of 172 patients (86 patients per group) were required to provide 80% power with a 2‐sided α level of 0.05 by the Student t test between 2 groups. With 10% of patients estimated to withdraw from participation during the study period, the final enrollment target was set at 190 patients (95 patients per group).

Efficacy analysis was performed according to the treatment to which patients were randomly assigned based on the intention‐to‐treat analysis. The primary outcome analysis was based on analysis of covariance for the change in ratio of BNP concentrations after 12 weeks from baseline. Adjusted covariates included the assigned treatment (luseogliflozin, voglibose), baseline age (<65 or ≥65 years), baseline hemoglobin A1c values (<8.0% or ≥8.0%), baseline BNP concentrations (<100 or ≥100 pg/mL), baseline renal function (eGFR ≥60 or <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2), use of thiazolidine at baseline, and presence or absence of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter at baseline as stratified factors of randomization. A similar method was used to analyze the secondary outcomes. Furthermore, the same analysis as that for the primary outcome was performed for the change in ratio of BNP concentrations after 4 and 24 weeks from baseline as sensibility analyses. For safety analysis, the primary population was all patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug. Analysis of safety outcomes (major adverse cardiovascular events, hypoglycemia, and urinary tract infection) was performed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test with the same stratification factors as those for the primary outcome. The consistency of drug effects was examined across 6 prespecified subgroups as stratified factors of randomization and the presence or absence of prior atherosclerotic cardiovascular events. All comparisons and analyses were 2‐sided with P<0.05 considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and Stata/SE 15.1 for Mac (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Study Population

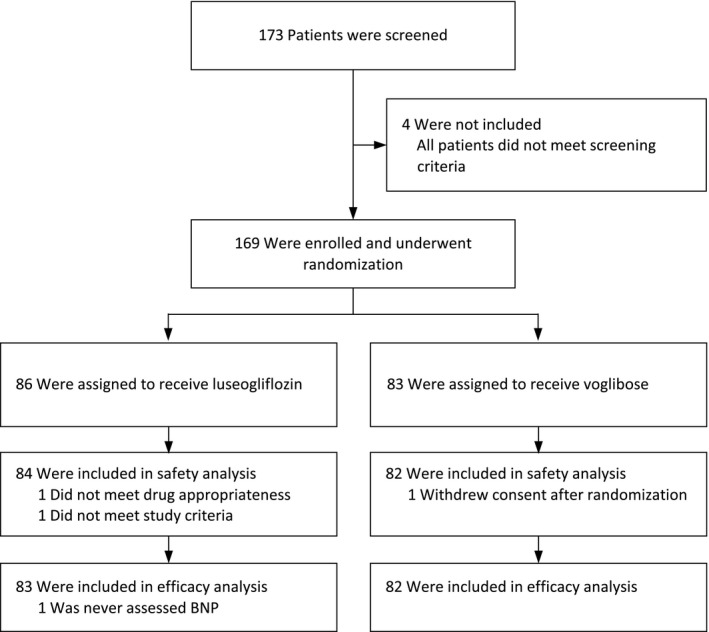

Between December 2015 and September 2018, a total of 173 patients from 16 hospitals and clinics had been screened for this study. A total of 169 patients were enrolled in this study. Of these patients, 86 were assigned to receive luseogliflozin and 83 to receive voglibose. Three (1.8%) patients did not receive any doses of a study drug and were prospectively excluded from all analyses. The safety analyses included a total of 166 patients. A total of 165 patients, with 83 in the luseogliflozin group and 82 in the voglibose group, who had BNP measurements assessed at least once were included in the efficacy analyses (Figure 11). High study drug adherence was observed in each hospital visit among the study population; the mean administration rate was 96.8% (luseogliflozin: 98.3%, voglibose: 95.2%).

Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

BNP indicates B‐type natriuretic peptide.

The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 11. The baseline variables were similar between the luseogliflozin and voglibose groups, except for the patients’ age because the majority of patients included in the study were aged ≥65 years. The mean age was significantly younger in patients in the luseogliflozin group than in the voglibose group (P=0.017). The rate of male sex was 66% and 59%, and the rate of patients with prior atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease was 59% and 62% in the luseogliflozin and voglibose groups, respectively. The majority of patients had mild heart failure symptoms at baseline. A total of 160 (97%) patients were classified as New York Heart Association class II, with no significant difference between the 2 groups. There was no significant difference in baseline medications between the 2 groups. More than half of the patients of this study were treated with specific heart failure treatment drugs, such as angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and beta‐blockers. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists were used in almost 20% of the patients. Antidiabetic medication was administered in 103 (62%) patients.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients

| Luseogliflozin (n=83) | Voglibose (n=82) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 71.7±7.7 | 74.6±7.7 | 0.017 |

| Median (interquartile range) | 72 (67–78) | 75 (70–79) | 0.027 |

| >60 y, n (%) | 77 (93) | 80 (98) | 0.152 |

| Male, n (%) | 55 (66) | 48 (59) | 0.31 |

| Body weight, kg | 64.6±12.7 | 63.5±13.1 | 0.57 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.4±4.3 | 25.3±4.4 | 0.85 |

| Waist circumflex, cm | 92.6±11.4 | 91.1±12.1 | 0.45 |

| NYHA class, n (%) | 0.44 | ||

| I | 0 | 0 | |

| II | 79 (96) | 81 (99) | |

| III | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| IV | 0 | 0 | |

| Duration of diabetes mellitus, mo | 72 (22–130) | 72 (36–138) | 0.90 |

| Prior diagnoses, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 72 (89) | 64 (79) | 0.087 |

| Hyperuricemia | 20 (25) | 24 (30) | 0.48 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 48 (59) | 50 (62) | 0.75 |

| Dyslipidemia | 65 (80) | 61 (75) | 0.45 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 29 (36) | 27 (33) | 0.74 |

| Hepatic disorder | 9 (11) | 3 (3.7) | 0.072 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 18 (22) | 15 (18) | 0.59 |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 51 (61) | 47 (57) | 0.59 |

| Beta‐blocker | 53 (64) | 47 (57) | 0.39 |

| MRA | 19 (23) | 20 (24) | 0.82 |

| Loop diuretic | 19 (23) | 19 (23) | 0.97 |

| Hydralazine | 5 (6.0) | 5 (6.1) | 0.98 |

| Antidiabetic medication | 53 (65) | 50 (61) | 0.74 |

| Hemodynamic parameters | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 131±17 | 128±14 | 0.168 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 71±11 | 71±10 | 0.52 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 69±13 | 70±12 | 0.53 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 7.0±0.7 | 6.9±0.8 | 0.52 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.5±1.6 | 13.1±1.6 | 0.114 |

| Hematocrit, % | 41.4±4.8 | 40.4±4.2 | 0.159 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 17.7±5.5 | 19.1±6.0 | 0.119 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.94±0.30 | 0.96±0.29 | 0.70 |

| Estimated GFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 60.6±19.4 | 56.8±16.5 | 0.185 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 63.7 (46.8–115.8) | 75.1 (42.4–120) | 0.87 |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 203 (123–389) | 200 (121–502) | 0.70 |

| High‐sensitivity CRP, mg/L | 0.91 (0.41–1.79) | 0.73 (0.25–1.66) | 0.48 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | |||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 57±9.4 | 58±9.4 | 0.41 |

| ≥50% | 53/73 (73) | 52/65 (80) | 0.31 |

| E/A | 0.77±0.21 | 0.85±0.29 | 0.094 |

| e′, cm/s | 5.4±1.5 | 5.6±1.8 | 0.66 |

| <8 cm/s | 68/71 (96) | 61/66 (92) | 0.40 |

| E/e′ | 13.0±4.5 | 13.3±5.6 | 0.67 |

| ≥13 | 24/71 (34) | 30/66 (46) | 0.163 |

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 42.0±7.4 | 42.5±7.9 | 0.69 |

| Left atrial volume index, mL/m2 | 37.9±16.3 | 38.4±13.5 | 0.84 |

| >34 mL/m2 | 35/68 (52) | 32/59 (54) | 0.76 |

| Left ventricular mass index, mL/m2 | 93.0±23.2 | 91.3±27.5 | 0.71 |

| ≥115 g/m2 for men or ≥95 g/m2 for women | 15/70 (21) | 13/63 (21) | 0.91 |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation, n (%), or median (interquartile range). ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin‐receptor blocker; BNP, B‐type natriuretic peptide; CRP, C‐reactive protein; E/A, ratio of early to atrial mitral inflow velocity; E/e′, ratio of early mitral inflow velocity to mitral annular early diastolic velocity; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; and NYHA, New York Heart Association.

The mean systolic blood pressure and heart rate were not significantly different between the 2 groups. At baseline, the median BNP concentration was 63.7 (interquartile range, 46.8–115.8) versus 75.1 pg/mL (interquartile range, 42.4–120) and the median NT‐proBNP concentration was 203 (interquartile range, 123–389) versus 200 pg/mL (interquartile range, 121–502) between the luseogliflozin and voglibose groups, respectively. No significant differences were observed in any cardiac‐related or other biomarker concentrations and echocardiographic parameters between the 2 groups.

Among all patients, the proportions of a left ventricular mass index ≥115 g/m2 for men or ≥95 g/m2 for women, left atrial volume index >34 mL/m2, e′ <8 cm/s, and E/e′ ≥13 were 21%, 53%, 94%, and 39%, respectively. The baseline echocardiographic parameters were similar between the luseogliflozin and voglibose groups.

Primary Outcome

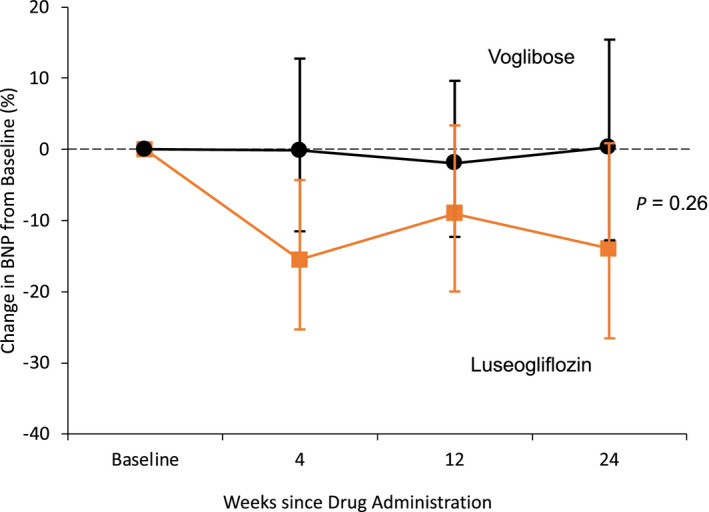

BNP concentrations decreased over time in the luseogliflozin group. A consistent decrease in BNP concentrations in the luseogliflozin group was observed after 4 and 24 weeks from baseline (Table 22). However, there was no significant difference in the reduction in BNP concentrations after 4 or 12 weeks compared with baseline between the 2 groups. The ratio of the mean BNP value at week 12 to the baseline value was 0.79 in the luseogliflozin group and 0.87 in the voglibose group (percent change, −9.0% versus −1.9%; ratio of change with luseogliflozin versus voglibose, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.78–1.10; P=0.26) (Figure 22).

Table 2.

Outcomes of the Patients in the 2 Groups

| Luseogliflozin (n=83) | Voglibose (n=82) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome, % (95% CI) | |||

| Change in ratio of BNP | |||

| After 4 wk from baseline | −15.48 (−25.32 to −4.33) | −0.13 (−11.56 to 12.78) | 0.108 |

| After 12 wk from baseline | −9.0 (−20.0 to 3.4) | −1.94 (−12.3 to 9.6) | 0.26 |

| After 24 wk from baseline | −13.99 (−26.65 to 0.85) | 0.31 (−12.80 to 15.38) | 0.133 |

| Main secondary efficacy outcomes, % (95% CI) | |||

| Change in E/e′ | 5.20 (−5.83 to 16.24) | 1.32 (−5.82 to 8.47) | 0.85 |

| Change in left ventricular ejection fraction | 2.78 (−2.66 to 8.21) | 2.95 (−1.38 to 7.30) | 0.62 |

| Change in body weight | −0.84 (−2.54 to 0.85) | −0.57 (−1.98 to 0.85) | 0.67 |

| Change in hemoglobin A1c | −1.87 (−3.31 to −0.44) | −1.19 (−3.18 to −0.81) | 0.71 |

| Safety outcomes | n=84 | n=82 | |

| Major adverse cardiovascular outcome | 0 | 0 | |

| Hypoglycemic adverse events | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0.49 |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0.49 |

| Any infection | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 1.0 |

| Severe hypotension | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1.0 |

| Elevation of blood pressure | 2 (2.3) | 0 | 0.50 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 0 | 6 (7.3) | 0.013 |

| Bone fracture | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0.49 |

| Fatigue | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 0.62 |

| Thirst | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1.0 |

| Exploratory hemodynamic and biomarker outcomes, % (95% CI) | |||

| Change in systolic blood pressure | −3.96 (−6.89 to −1.03) | 0.54 (−2.23 to 3.32) | 0.036 |

| Change in heart rate | 0.49 (−3.48 to 4.45) | 2.62 (−1.56 to 6.80) | 0.39 |

| Change in estimated GFR | −4.26 (−7.20 to −1.32) | −0.83 (−3.35 to 1.69) | 0.061 |

| Change in NT‐pro‐BNP | −8.43 (−19.84 to 4.60) | −5.50 (−15.17 to 5.27) | 0.56 |

| Change in high‐sensitivity CRP | 22.47 (−1.65 to 52.52) | 9.97 (−18.13 to 47.71) | 0.55 |

| Change in E/A | 3.42 (−2.48 to 9.33) | 6.95 (−1.78 to 15.7) | 0.57 |

| Change in e′ | 1.22 (−9.08 to 11.5) | 2.46 (−6.26 to 11.2) | 0.82 |

| Change in left atrial diameter | 2.37 (−1.23 to 5.96) | −1.34 (−5.17 to 2.49) | 0.105 |

| Change in left atrial volume index | −4.49 (−14.6 to 5.62) | −0.62 (−11.8 to 10.6) | 0.51 |

| Change in left ventricular mass index | −4.23 (−11.9 to 3.41) | 2.29 (−3.66 to 8.24) | 0.31 |

Data are presented as 95% CIs or n (%). BNP indicates B‐type natriuretic peptide; CRP, C‐reactive protein; E/A, ratio of early to atrial mitral inflow velocity; E/e′, ratio of early mitral inflow velocity to mitral annular early diastolic velocity; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; and NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide.

Figure 2. Change in BNP concentrations.

No significant difference was observed in the reduction in BNP concentrations after 12 weeks compared with baseline between the two groups. The ratio of the mean BNP value at week 12 to the baseline value was 0.79 in the luseogliflozin group and 0.87 in the voglibose group (percent change, −9.0% vs −1.9%, ratio of change with luseogliflozin vs voglibose, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.78–1.10; P=0.26). BNP indicates B‐type natriuretic peptide.

Secondary and Safety Outcomes

The change in E/e′, left ventricular EF, body weight, and hemoglobin A1C levels after 12 weeks in the luseogliflozin group were not significantly different from those in the voglibose group (Table 22). The main safety outcomes, including major adverse cardiovascular events, hypoglycemic adverse events, and urinary tract infection, were not significantly different between the groups (Table 22). No significant difference was observed in other adverse events between the groups. However, the rate of gastrointestinal symptoms in the voglibose group was significantly higher than that in the luseogliflozin group (P=0.013). Exploratory hemodynamic and biomarker outcomes are shown in Table 22. No significant differences were observed in the change in heart rate, eGFR, NT‐proBNP concentrations, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein concentrations, E/A, e′, left atrial diameter, left atrial volume index, and left ventricular mass index between the groups. However, a significantly greater reduction in systolic blood pressure after 12 weeks compared with baseline was observed in the luseogliflozin group than in the voglibose group (P=0.036).

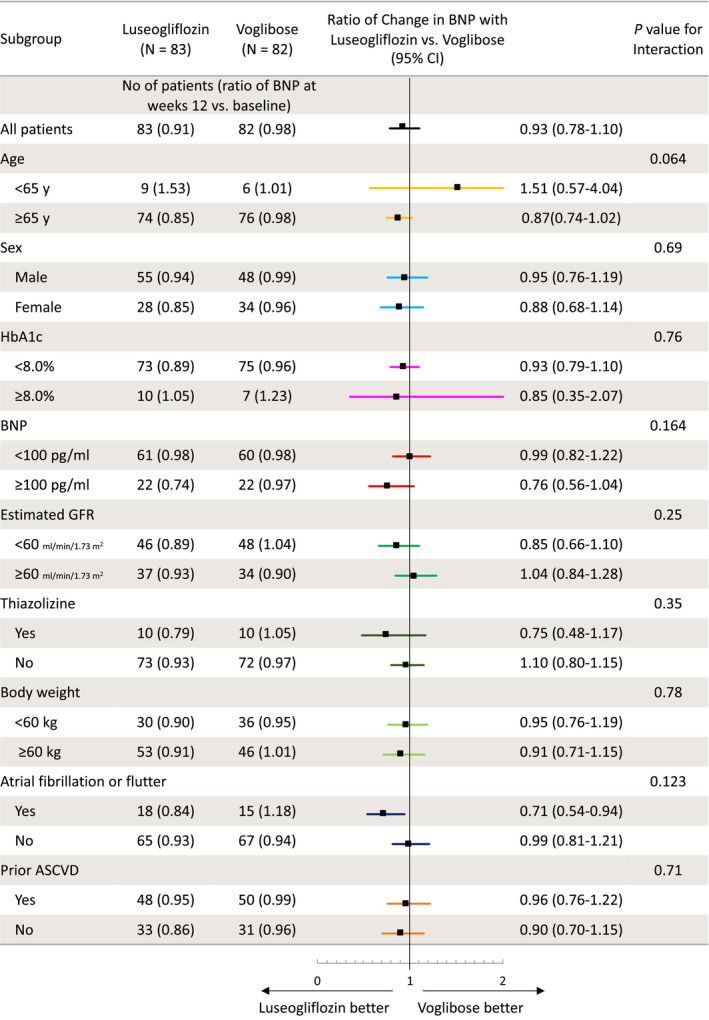

Subgroup Analyses

No statistical significance was observed in the interaction between the effect of study drugs and prespecified patient subgroups (Figure 33).

Figure 3. Subgroup analyses of the change in BNP concentrations.

Data on the change in ratio of BNP concentrations from baseline to 12 weeks with each treatment according to subgroup are shown. ASCVD indicates atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BNP, B‐type natriuretic peptide; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; and HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

Discussion

The MUSCAT‐HF study is the first prospective, multicenter, open‐label, randomized, controlled trial to investigate the drug effect of an SGLT2 inhibitor, luseogliflozin, on BNP concentrations as the primary outcome compared with an alpha‐glucosidase inhibitor, voglibose. We found that BNP concentrations decreased after initiation of either luseogliflozin or voglibose. There was no significant difference in the degree of reduction in BNP concentrations after 12 weeks for luseogliflozin and voglibose. There were no significant differences in the main secondary and safety outcomes, except for gastrointestinal symptoms, between the groups.

Some randomized controlled trials reported that SGLT2 inhibitors robustly reduced cardiovascular adverse events, including hospitalization of heart failure, in patients with diabetes mellitus.7, 8, 9 In an exploratory analysis from DECLARE‐TIMI 58 (Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 58), hospitalization for heart failure in patients with heart failure with reduced EF (<45%) at baseline was significantly reduced, while this reduction in hospitalization for heart failure was not observed in patients with HFpEF.18 A recent randomized trial showed that dapagliflozin decreased worsening heart failure in patients with heart failure with reduced EF, regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes mellitus.10 However, the benefit of an SGLT2 inhibitor in patients with HFpEF on hospitalization for heart failure remains unestablished. This study specifically focused on patients with HFpEF using BNP concentrations. Although BNP was a surrogate end point for heart failure, use of the primary outcome of the change in ratio of BNP concentrations after 12 weeks of treatment from baseline was a strength of this study. Additionally, selection of participants to clearly target patients with HFpEF was an advantage of this study. Under this specific study design, this study showed no significant effect on the change in BNP concentrations from baseline with an SGLT2 inhibitor compared with an alpha‐glucosidase inhibitor.

We consider that there were various factors that reduced the effect of an SGLT2 inhibitor in this study. First, the majority of patients who were enrolled in our study were at low risk. Almost all patients had New York Heart Association class II symptoms and low BNP levels at baseline. Only 23% of patients were receiving a loop diuretic at baseline, and had relatively lower use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin‐receptor blockers at baseline. Additionally, a total of 40% patients did not have prior atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Previous reports have shown greater effectiveness of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with prior myocardial infarction or a high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease than in those without these conditions.19, 20 Therefore, patients without these conditions may have had less effectiveness of SGLT2 inhibitors in this study. Second, in our study, luseogliflozin and voglibose reduced BNP levels by 9.0% and 1.9%, respectively, but this difference was not significant. One explanation for this lack of significance is that this study was not sufficiently powered for moderate differences that were actually observed. With a power of 80% and a sample size of 86 per group, we could statistically detect up to a 30% difference between the 2 groups. Underpowered analysis is susceptible to a type II error. The effect size of a reduction in BNP concentrations in this study was lower than we expected, probably attributable to patients with mild heart failure.

In this study, HFpEF was defined as a left ventricular EF ≥45%, BNP concentrations ≥35 pg/mL, and any symptoms. This definition was modified according to the 2012 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) heart failure guidelines.13 The cutoff of the EF for definition of HFpEF in other clinical trials varied from 40% to 50%.1, 4, 21, 22 The 2012 ESC heart failure guidelines stated that patients with HF and an EF ≥50% are considered as having HFpEF, while patients with an EF ranging from 35% to 50% represent a “gray area.”13 The 2013 US guideline stated that HFpEF included an EF >40%.5 Based on these documents, we recruited patients with an EF ≥45% as HFpEF. With regard to the relevance of structural heart disease, a comprehensive echocardiographic examination was recommended at enrollment in the study. We checked the presence of structural and functional echocardiographic measures as listed in the 2012 ESC heart failure guidelines.13 Patients who had at least 1 of these measurements, including left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, comprised 97% of the study population. Therefore, we consider that almost all of the study population fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of HFpEF in the 2012 ESC heart failure guidelines.13

Our study showed a reduction in BNP concentrations in the luseogliflozin group at 4 weeks, which suggested that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce cardiac load immediately after their introduction. Further, luseogliflozin significantly reduced systolic blood pressure compared with voglibose. However, echocardiographic parameters of left ventricular systolic or diastolic function (eg, left ventricular EF and E/e′) were similar between the groups. Interestingly, the left atrial volume index and left ventricular mass index appeared to be reduced after luseogliflozin, but this was not significant. Our research group has reported that an SGLT2 inhibitor ameliorated cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in hypertensive rats that were fed a high‐fat diet.23 Some studies have also shown that SGLT2 inhibition improves arterial stiffness and achieves lowering of blood pressure in patients with diabetes mellitus.24, 25, 26 From the results of subgroup analyses, luseogliflozin use tended to be higher in patients with an older age, BNP levels >100 pg/mL at baseline, and atrial arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation or flutter). We consider that these patients’ characteristics are representative of heart failure with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Therefore, selectively using SGLT2 inhibitors might be beneficial for such patients with severe left ventricular diastolic dysfunction or cardiac afterload, even those with HFpEF. Further detailed studies are required, including ongoing randomized controlled trials.27, 28, 29

This study has several limitations. First, this study was not blinded and was an open‐label study. Second, the primary outcome of this study was the change in BNP concentrations after 12 weeks of treatment from baseline. This was a surrogate end point, and the follow‐up duration was short. Third, the predefined sample size of 190 was not achieved. We started the study, which was designed to be conducted for almost 2 years, for the enrollment period from December 2015. However, the study population did not reach a number required for sufficient statistical power during the prespecified enrollment period. Therefore, we extended the enrollment period to 3 years until September 2018. Unfortunately, the study included only 169 patients. We could not continue enrollment of new patients because of a shortage of funds. Fourth, there were more patients with mild heart failure in this study than expected. Therefore, differences between study groups might have been diminished. Furthermore, the effect of luseogliflozin on BNP levels in patients with diabetes mellitus and HFpEF might have been overestimated, and the sample size calculation might not have been sufficient for estimating differences between the study groups. Finally, the latest definition of HFpEF in the ESC heart failure guidelines has changed since 2012. In the 2016 ESC heart failure guidelines,6 patients with a left ventricular EF ranging from 40% to 49% are newly defined as HF with midrange EF. On the basis of the latest ESC heart failure guidelines,6 24% of patients with a left ventricular EF of <50% in this study did not fulfill the definition of HFpEF.

In conclusion, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and HFpEF, initiation of luseogliflozin does not significantly reduce BNP concentrations over a 12‐week follow‐up compared with voglibose.

Appendix

The MUSCAT‐HF Study Investigators

Kentaro Ejiri (Tamano City Hospital and Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Density and Pharmaceutical Sciences); Toru Miyoshi, Kazufumi Nakamura, and Hiroshi Ito (Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Density and Pharmaceutical Sciences); Hajime Kihara (Kihara Cardiovascular Clinic); Yoshiki Hata (Minamino Cardiovascular Hospital); Toshihiko Nagano (Iwasa Hospital); Atsushi Takaishi (Mitoyo General Hospital); Hironobu Toda (Okayama East Neurosurgery Hospital and Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Density and Pharmaceutical Sciences); Seiji Namba (Okayama Rosai Hospital); Yoichi Nakamura (Specified Clinic of Soyokaze Cardiovascular Medicine and Diabetes Care); Satoshi Akagi (Akaiwa Medical Association Hospital and Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Density and Pharmaceutical Sciences); Satoru Sakuragi (Iwakuni Clinical Center); Taro Minagawa (Minagawa Cardiovascular Clinic); Yusuke Kawai (Okayama City Hospital); Nobuhiro Nishii (Yoshinaga Hospital and Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Density and Pharmaceutical Sciences); Tetsuya Sato and Soichiro Fuke (Japanese Red Cross Okayama Hospital); Masaki Yoshikawa and Hiroyasu Sugiyama (Fukuyama City Hospital); Michio Imai (Imai Heart Clinic); Naoki Gotoh (Gotoh Clinic); Tomonori Segawa (Asahi University Hospital); Toshiyuki Noda (Gifu Prefectural General Medical Center); and Masatoshi Koshiji (Gifu Seiryu Hospital).

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by Novartis Pharma K. K.

Disclosures

Dr Miyoshi received a trust research/joint research fund from Novartis Pharma K. K. Dr Nishii is affiliated with the endowment department of Medtronic Japan. Dr Ito received a trust research/joint research fund from Novartis KK. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1–S3 Figure S1 Table S1 References 15–17

Acknowledgments

We thank Tetsutaro Hamano, MS, for his assistance in the study's design and statistical analysis.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015103 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015103.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

See Editorial by Silva Enciso

Contributor Information

Toru Miyoshi, Email: miyoshit@cc.okayama-u.ac.jp.

MUSCAT‐HF Study Investigators:

Tetsuya Sato, Hiroyasu Sugiyama, Michio Imai, Naoki Gotoh, Tomonori Segawa, Toshiyuki Noda, and Masatoshi Koshiji

References

- 1. Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, et al. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1383–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cleland JGF, Bunting KV, Flather MD, Altman DG, Holmes J, Coats AJS, Manzano L, McMurray JJV, Ruschitzka F, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Beta‐blockers for heart failure with reduced, mid‐range, and preserved ejection fraction: an individual patient‐level analysis of double‐blind randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cleland JG, Tendera M, Adamus J, Freemantle N, Polonski L, Taylor J. The perindopril in elderly people with chronic heart failure (PEP‐CHF) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2338–2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Zile MR, Anderson S, Donovan M, Iverson E, Staiger C, et al. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2456–2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, Gonzalez‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Law G, Desai M, Matthews DR. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:644–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, Silverman MG, Zelniker TA, Kuder JF, Murphy SA, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Kober L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Anand IS, Belohlavek J, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Karasik A, Laakso M. Acarbose treatment and the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: the STOP‐NIDDM trial. JAMA. 2003;290:486–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ejiri K, Miyoshi T, Nakamura K, Sakuragi S, Munemasa M, Namba S, Takaishi A, Ito H. The effect of luseogliflozin and alpha‐glucosidase inhibitor on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in diabetic patients: rationale and design of the MUSCAT‐HF randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez‐Sanchez MA, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Washburn WN, Poucher SM. Differentiating sodium‐glucose co‐transporter‐2 inhibitors in development for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22:463–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rousseau MF, Gurne O, Duprez D, Van Mieghem W, Robert A, Ahn S, Galanti L, Ketelslegers JM. Beneficial neurohormonal profile of spironolactone in severe congestive heart failure: results from the RALES neurohormonal substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1596–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsutamoto T, Wada A, Maeda K, Mabuchi N, Hayashi M, Tsutsui T, Ohnishi M, Sawaki M, Fujii M, Matsumoto T, et al. Effect of spironolactone on plasma brain natriuretic peptide and left ventricular remodeling in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1228–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Solomon SD, Zile M, Pieske B, Voors A, Shah A, Kraigher‐Krainer E, Shi V, Bransford T, Takeuchi M, Gong J, et al. The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a phase 2 double‐blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1387–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kato ET, Silverman MG, Mosenzon O, Zelniker TA, Cahn A, Furtado RHM, Kuder J, Murphy SA, Bhatt DL, Leiter LA, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on heart failure and mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2019;139:2528–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Furtado RHM, Bonaca MP, Raz I, Zelniker TA, Mosenzon O, Cahn A, Kuder J, Murphy SA, Bhatt DL, Leiter LA, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and previous myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2019;139:2516–2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, Im K, Goodrich EL, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, Furtado RHM, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet. 2019;393:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J; Investigators C . Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left‐ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM‐Preserved Trial. Lancet. 2003;362:777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Redfield MM, Anstrom KJ, Levine JA, Koepp GA, Borlaug BA, Chen HH, LeWinter MM, Joseph SM, Shah SJ, Semigran MJ, et al. Isosorbide mononitrate in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2314–2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kimura T, Nakamura K, Miyoshi T, Yoshida M, Akazawa K, Saito Y, Akagi S, Ohno Y, Kondo M, Miura D, et al. Inhibitory effects of tofogliflozin on cardiac hypertrophy in Dahl salt‐sensitive and salt‐resistant rats fed a high‐fat diet. Int Heart J. 2019;60:728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heerspink HJ, Perkins BA, Fitchett DH, Husain M, Cherney DZ. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: cardiovascular and kidney effects, potential mechanisms, and clinical applications. Circulation. 2016;134:752–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chilton R, Tikkanen I, Cannon CP, Crowe S, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Johansen OE. Effects of empagliflozin on blood pressure and markers of arterial stiffness and vascular resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:1180–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cherney DZ, Perkins BA, Soleymanlou N, Har R, Fagan N, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, von Eynatten M, Broedl UC. The effect of empagliflozin on arterial stiffness and heart rate variability in subjects with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos GS, Jamal W, Salsali A, Schnee J, Kimura K, Zeller C, George J, Brueckmann M, et al. Evaluation of the effects of sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 inhibition with empagliflozin on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: rationale for and design of the EMPEROR‐Preserved Trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1279–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dapagliflozin evaluation to improve the LIVEs of patients with preserved ejection fraction heart failure. (DELIVER). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03619213. Accessed May 10, 2020.

- 29. Dapagliflozin in preserved ejection fraction heart failure (PRESERVED‐HF). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03030235. Accessed May 10, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1–S3 Figure S1 Table S1 References 15–17