Abstract

Background

Greater physical activity (PA) is associated with lower heart failure (HF) risk. However, it is unclear whether this inverse association exists across all subgroups at high risk for HF, particularly among those with preexisting atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Methods and Results

We followed 13 810 ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study participants (mean age 55 years, 54% women, 26% black) without HF at baseline (visit 1; 1987–1989). PA was assessed using a modified Baecke questionnaire and categorized according to American Heart Association guidelines: recommended, intermediate, or poor. We constructed Cox models to estimate associations between PA categories and incident HF within each high‐risk subgroup at baseline, with tests for interaction. We performed additional analyses modeling incident coronary heart disease as a time‐varying covariate. Over a median of 26 years of follow‐up, there were 2994 HF events. Compared with poor PA, recommended PA was associated with lower HF risk among participants with hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome (all P<0.01), but not among those with prevalent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease, stroke, or peripheral arterial disease) (hazard ratio, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.74–1.13 [P interaction=0.02]). Recommended PA was associated with lower risk of incident coronary heart disease (hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.72–0.86), but not with lower HF risk in those with interim coronary heart disease events (hazard ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.78–1.04 [P interaction=0.04]).

Conclusions

PA was associated with decreased HF risk in patients with hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome. Despite a myriad of benefits in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, PA may have weaker associations with HF prevention after ischemic disease is established.

Keywords: epidemiology, exercise, heart failure, lifestyle, primary prevention

Subject Categories: Epidemiology, Lifestyle, Exercise, Primary Prevention, Heart Failure

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACCF

American College of Cardiology Foundation

- AHA

American Heart Association

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- ASCVD

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- BMI

body mass index

- BP

blood pressure

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HDL‐C

high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HF

heart failure

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- IQR

interquartile range

- LDL

low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MET

metabolic equivalent of task

- PA

physical activity

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This study demonstrates that higher levels of physical activity are associated with lower risk of heart failure (HF) in various high‐risk subgroups, including patients with hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome.

However, the majority of individuals with these high‐risk conditions are not achieving recommended physical activity levels.

The study also found that despite the numerous health‐related benefits of physical activity, it may be less effective for HF prevention once atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is established.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Physical activity should be strongly promoted as part of strategies for HF prevention among all high‐risk subgroups.

However, given the potentially weaker associations with HF prevention in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, additional evidence‐based strategies for HF prevention should be emphasized for this population.

Introduction

Improved survival of patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) and aging of the population have contributed to the rising prevalence of heart failure (HF).1 According to the American Heart Association (AHA), ≈1 000 000 new cases of HF occur yearly, resulting in more than 6.5 million Americans being affected by this syndrome.2 In addition to its high prevalence, HF is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.3 Despite advances in treatment, studies have shown that 50% to 75% of patients with HF will die within 5 years of diagnosis.4 Development of strategies to prevent HF is of utmost importance, with potential for a large public health impact.5 Specifically, refining and implementing targeted interventions focused on high‐risk individuals could have important clinical implications for HF prevention.

To emphasize the need for HF prevention, current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) and the AHA utilize a staging system, ranging from stage A (asymptomatic and without structural heart disease, but at high risk) to stage D (end‐stage) HF.6 The category of stage A HF includes patients with hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), each of which is a potent independent risk factor for HF.7 Current guidelines broadly recommend adherence to a heart‐healthy lifestyle, including engaging in recommended levels of physical activity (PA), as part of strategies to ideally prevent these HF risk factors from developing in the first place (primordial prevention), but, if already present, to prevent development of HF in these high‐risk subgroups.6 However, complex and distinct mechanisms underlie the HF risk associations for each of these subgroups. Therefore, it is unclear whether the same preventive strategies will be uniformly protective across these high‐risk groups.

Observational studies have consistently shown a dose‐dependent inverse association between PA and incident HF.8 In addition to favorable effects on traditional risk factors, PA may improve insulin resistance, inflammation, subclinical myocardial damage, and the adverse ventricular remodeling that underlie the associations between HF and cardiometabolic conditions such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome.9, 10 While PA is known to protect against the development of ASCVD and likely improves survival after ischemic events, PA may be less effective in preventing HF as a result of myocyte death and replacement fibrosis as a consequence of established ischemic heart disease. The relative impact of adhering to guideline‐recommended levels of PA among the various subgroups at high risk for HF has not been determined.

In this analysis of the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study, we sought to evaluate the associations of PA with incident HF among subgroups considered at high risk for incident HF in the current ACCF/AHA guidelines. A priori, we hypothesized that PA would be less strongly associated with reduced HF risk among individuals with prevalent self‐reported ASCVD than in other high‐risk subgroups.

Methods

Anonymized data from the ARIC study are available through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center. Interested researchers may additionally contact the ARIC study Coordinating Center to access the study data.

Study Design and Population

The ARIC study is an ongoing prospective observational cohort of mostly black and white adults from 4 US communities (Forsyth Country, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; suburban Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Washington County, Maryland). Between 1987 and 1989, 15 792 participants aged 45 to 64 years were enrolled in the study. After the baseline visit, 3 more study visits occurred triennially (visit 2 in 1990–1992, visit 3 in 1993–1995, and visit 4 in 1996–1999), and a fifth and a sixth study visit were completed in 2011–2013 and 2016–2017, respectively. Participants were also followed by annual or semiannual telephone interviews and active surveillance of ARIC community hospitals. Further details on study design have been previously published.11 The institutional review boards for each study site reviewed and approved the study protocol and all participants provided informed consent. After excluding participants who were not of black or white race (n=48), those with prevalent HF or no HF information at visit 1 (n=1035), those missing data on PA (n=14), and those missing data on high‐risk subgroups at baseline (n=885), 13 810 individuals were included in the current analysis.

Physical Activity

The primary exposure variable was exercise PA assessed at visit 1, which was evaluated by the interviewer‐administered Baecke questionnaire that has been previously described.12 Participants answered questions about participation in up to 4 sports or exercise activities, as well as the frequency in which they engaged in such activities. Commuting and other leisure time activities were not considered in this study. Each activity was assigned a metabolic equivalent of task (MET), corresponding to those found in the compendium of PAs, and the total volume of PA was converted into MET×minutes per week.13

We then categorized PA according to AHA and the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommendations14, 15 as poor (0 min/wk of moderate or vigorous PA), intermediate (>0 min/wk of moderate or vigorous PA but less than recommended), and recommended (≥75 min/wk of vigorous or ≥150 min/wk of moderate and/or vigorous PA). Moderate PA was defined as a workload of 3 to 6 METs and vigorous PA as >6 METs. We also modeled PA as a continuous variable in MET×minutes per week, with scaling per 1 SD. PA was additionally assessed at visit 3 (n=11 387; 6 years after baseline).

High‐Risk Subgroups and Additional Covariates

We defined the subgroups at high risk for HF according to the most recent ACCF/AHA guidelines.6 Individuals with hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and prevalent ASCVD at baseline (visit 1) were considered at high risk for HF. Blood pressure (BP) was measured 3 times after 5 minutes of rest and recorded as the average of the last 2 measurements. Hypertension was defined as a systolic BP ≥130 mm Hg, a diastolic BP ≥80 mm Hg, or the use of antihypertensive medications.16 Height and weight were measured by trained personnel and used to calculate body mass index. Obesity was defined as a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2.

Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed by the presence of fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL, random blood glucose ≥200 mg/dL, use of hypoglycemic agents, and/or a self‐reported prior diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Metabolic syndrome was defined according AHA/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines as the presence of 3 of the following 5 components: (1) abdominal obesity (waist circumference ≥102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women); (2) elevated BP (systolic BP ≥130 mm Hg, diastolic BP ≥85 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive medications; (3) impaired fasting glucose (fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL), without a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus; (4) low high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (≤40 mg/dL in men or 50 mg/dL in women); and (5) elevated triglycerides (≥150 mg/dL). Prevalent ASCVD was defined as a self‐reported prior physician diagnosis of CHD or stroke, or peripheral arterial disease diagnosed by a measured arterial‐brachial index ≤0.9.

Sex and race were self‐identified. Smoking status was self‐reported and participants were categorized as current, former, or never smokers. Average alcohol consumption was also self‐reported and subsequently converted to grams per week. High‐sensitivity cardiac troponin T and N‐terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide were measured from plasma samples collected at visit 2 using the sandwich immunoassay method on the Roche Elecsys 2010 Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics Corporation). Elevated high‐sensitivity cardiac troponin T was defined as ≥14 ng/L and elevated N‐terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide was defined as ≥100 pg/mL, as in prior ARIC studies.

Outcome Assessment

The primary outcome of interest was incident HF, defined as a HF‐associated hospitalization or death occurring after the baseline examination (visit 1) until December 31, 2016. Incident HF was diagnosed from hospitalizations or deaths with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) discharge code, in any position, beginning with 428 in early follow‐up, or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10) I50 in later follow‐up, and from deaths with either of these codes as the underlying cause of death.

Statistical Analysis

We performed univariate comparisons of baseline characteristics of study participants according to PA category (poor, intermediate, or recommended) at visit 1. ANOVA was used for continuous variables and chi‐square test for categorical variables.

We constructed Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the association of each high‐risk subgroup (hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and prevalent ASCVD) with incident HF. Our regression models were adjusted for the confounders of age, sex, race, smoking status (never, former, or current smoker), and alcohol intake.

We subsequently assessed the associations between PA and HF in the overall sample and with stratification by each high‐risk subgroup. We used Poisson regression to calculate HF incidence rates within each PA category at mean levels of age, sex, race, smoking status, and alcohol intake, and calculated the P for trend across PA categories. Using patients with poor PA as the reference group, we also constructed multivariate Cox regression models to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) for HF associated with intermediate and recommended levels of PA for the overall study sample and among participants with and without each high‐risk characteristic. We additionally evaluated the continuous association of PA (per 1‐SD, 874.8 MET×min/wk) with incident HF among patients with and without each high‐risk characteristic. We used multiplicative interaction terms to test for interactions between each high‐risk subgroup and PA category (recommended versus poor) on the outcome of incident HF.

To further evaluate the association between PA and incident HF among patients with ASCVD, we performed several sensitivity analyses. First, we repeated the analyses above excluding any HF events in the first 2 years of follow‐up to address possible reverse causation. We conducted analyses using restricted cubic spline models to explore possible nonlinear associations of continuous PA (MET×min/wk) with incident HF among participants with and without ASCVD. We compared the baseline characteristics of participants in the 3 PA categories stratified by the presence of ASCVD. We also performed analyses defining patients with CHD (rather than the broader population with ASCVD) at visit 1 as a high‐risk subgroup.

We performed additional regression analyses to evaluate the relationship between PA, incident CHD, and HF subsequent to ischemic events. We constructed Cox regression models to assess the association between higher categories of PA and the risk of incident CHD. Then, modeling incident CHD as a time‐varying covariate, to account for incident ischemic events preceding the development of HF, we performed Cox regression analyses assessing the association of PA with HF risk with time‐varying CHD included in the model. We used this model to estimate the association of PA with HF among patients who did and did not experience interim CHD events. We additionally tested for an interaction between PA category (recommended versus poor) and incident CHD on the outcome of HF.

In further sensitivity analyses, we used visit 3 as a new baseline and evaluated the associations of cross‐categories of PA at visits 1 and 3 (poor at both time points, recommended at both time points, or another combination) with incident HF among patients with and without CHD at visit 3. The definition of prevalent CHD at visit 3 included the presence of prevalent CHD at visit 1 and adjudicated CHD cases (fatal and nonfatal MI, silent MI, or coronary revascularization procedure) from visit 1 through visit 3.

All P values presented are 2‐sided. The analyses were performed using STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Of the 13 810 participants included in this study, 37% reported poor, 25% intermediate, and 39% recommended levels of PA at baseline (visit 1). The mean age of participants was 55 years, 54% were women, and 26% were black. Individuals in the highest versus the lowest category of PA were less likely to be women, of black race, current smokers, to have hypertension or diabetes mellitus, and had lower body mass index and higher high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample at Visit 1 (1987–1989) by PA

| PA Category | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Intermediate | Recommended | ||

| No. (%) | 5084 (36.8) | 3411 (24.7) | 5315 (38.5) | |

| Age, y | 54.4 (5.7) | 54.4 (5.7) | 54.8 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Black, No. (%) | 2015 (39.6) | 750 (22.0) | 806 (15.2) | <0.001 |

| Women, No. (%) | 2931 (57.7) | 2001 (58.7) | 2559 (48.1) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.5 (5.7) | 27.4 (5.1) | 26.8 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | |||

| Never smoker, No. (%) | 2075 (40.9) | 1510 (44.3) | 2232 (42.0) | |

| Former smoker, No. (%) | 1391 (27.4) | 1074 (31.5) | 2028 (38.2) | |

| Current smoker, No. (%) | 1613 (31.8) | 826 (24.2) | 1053 (19.8) | |

| Alcohol intake, g/wk | 41.5 (107.5) | 39.6 (87.4) | 45.1 (85.3) | 0.022 |

| Diabetes mellitus, No. (%) | 716 (14.1) | 349 (10.2) | 472 (8.9) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive, No. (%) | 1588 (31.2) | 893 (26.2) | 1290 (24.3) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 123.4 (19.9) | 120.0 (18.0) | 119.2 (17.5) | <0.001 |

| HDL‐C, mg/dL | 51.2 (17.1) | 51.8 (16.5) | 52.0 (17.3) | 0.033 |

| LDL‐C, mg/dL | 138.4 (40.1) | 137.8 (38.8) | 137.0 (38.3) | 0.204 |

| Triglycerides, median (IQR), mg/dL | 111 (79–157) | 109 (78–154) | 107 (76–154) | 0.018 |

| eGFR, median (IQR), mL/min per 1.732 | 105 (96–115) | 103 (95–111) | 101 (94–109) | <0.001 |

Values are means and SDs or number and proportion unless otherwise indicated. BMI indicates body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; IQR, interquartile range; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; and PA, physical activity.

Within the study population, there were 6896 (49.9%) participants with hypertension, 3662 (26.5%) with obesity, 1537 (11.1%) with diabetes mellitus, 3110 (22.5%) with metabolic syndrome, and 1251 (9.1%) with prevalent ASCVD. Within each of the high‐risk groups, the number and proportion of individuals reporting recommended PA was 2397 (34.8%) in those with hypertension, 1075 (29.4%) in those with obesity, 472 (30.7%) in those with diabetes mellitus, 1207 (38.8%) in those with metabolic syndrome, and 495 (39.6%) in those with prevalent ASCVD. Over a median 26.0 years of follow‐up, there were 2994 incident HF events. As expected, each high‐risk characteristic was strongly associated with incident HF when compared with those without the high‐risk characteristic, with HRs for HF ranging from 2.04 to 3.14 (Table 2).

Table 2.

HRs and 95% CI for Incident HF Associated With Each High‐Risk Subgroupa

| ASCVD (n=1251) | 2.54 (2.30–2.80) |

| Hypertension (n=6896) | 2.04 (1.89–2.21) |

| Obesity (n=3662) | 2.04 (1.89–2.20) |

| Diabetes mellitus (n=1537) | 3.14 (2.88–3.43) |

| Metabolic syndrome (n=3110) | 2.08 (1.91–2.26) |

ASCVD indicates atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; and HRs, hazard ratios.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

Each high‐risk subgroup was modeled separately and compared with pastients without that respective high‐risk feature.

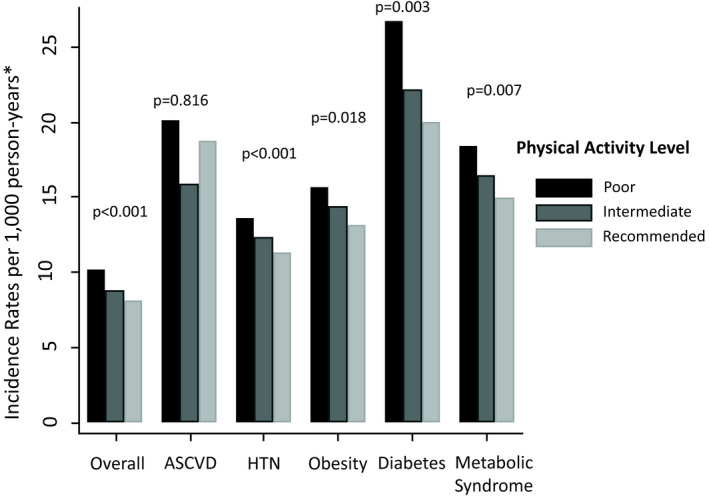

Adjusted incidence rates for HF (per thousand person‐years) in the overall study sample were 10.2 for patients with poor PA, 8.8 for patients with intermediate PA, and 8.1 for patients with recommended PA. As shown in the Figure, higher levels of PA were associated with lower rates of incident HF among participants with hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome (all P for trend <0.01). However, among patients with prevalent ASCVD, incident HF rates were not significantly lower at higher PA (P for trend=0.82).

Figure 1. Adjusted incidence rates of heart failure according to physical activity category, overall and within high‐risk subgroups.

*At mean age, sex, race, smoking status, and alcohol intake. ASCVD indicates atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

In multivariate Cox regression analyses, in the overall study sample, we found that patients with recommended levels of PA had a HR of 0.78 (95% CI, 0.72–0.85) for incident HF compared with those with poor PA (Table 3). Compared with poor PA, recommended PA was associated with lower HF risk among those with hypertension (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73–0.91), obesity (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.71–0.95), diabetes mellitus (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.60–0.87), and metabolic syndrome (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69–0.92), as well as among those without these conditions. A significant interaction was present between diabetes mellitus and PA, although recommended PA was associated with significantly lower HF risk among those with and without diabetes mellitus.

Table 3.

Adjusted HRs and 95% CI for Incident HF Associated With Higher Category of PA, Overall and Among Participants With or Without a High‐Risk Characteristica

| PA Category | P for Interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Intermediate | Recommended | ||

| Overall (N=13 810) | Reference (1) | 0.86 (0.78–0.94) | 0.78 (0.72–0.85) | |

| No ASCVD (n=12 559) | Reference (1) | 0.87 (0.79–0.96) | 0.74 (0.68–0.82) | 0.02 |

| ASCVD (n=1251) | Reference (1) | 0.78 (0.61–1.01) | 0.91 (0.74–1.13) | |

| No hypertension (n=6914) | Reference (1) | 0.83 (0.70–0.97) | 0.79 (0.69–0.92) | 0.45 |

| Hypertension (n=6896) | Reference (1) | 0.91 (0.81–1.02) | 0.82 (0.73–0.91) | |

| No obesity (n=10 148) | Reference (1) | 0.88 (0.78–0.99) | 0.84 (0.75–0.94) | 0.81 |

| Obesity (n=3662) | Reference (1) | 0.93 (0.80–1.08) | 0.82 (0.71–0.95) | |

| No diabetes mellitus (n=12 273) | Reference (1) | 0.90 (0.81–1.00) | 0.83 (0.75–0.91) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n=1537) | Reference (1) | 0.82 (0.68–1.01) | 0.72 (0.60–0.87) | |

| No metabolic syndrome (n=10 700) | Reference (1) | 0.87 (0.77–0.97) | 0.81 (0.73–0.90) | 0.70 |

| Metabolic syndrome (n=3110) | Reference (1) | 0.89 (0.76–1.04) | 0.79 (0.69–0.92) | |

ASCVD indicates atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; HRs, hazard ratios; and PA, physical activity.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

In contrast, among patients with prevalent ASCVD, there was no significant association between higher PA categories and incident HF (HR for recommended versus poor PA, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.74–1.13) (Table 3). Additionally, a significant statistical interaction was found between prevalent ASCVD and PA on the outcome of incident HF (P=0.02). Results were similar after exclusion of HF events in the first 2 years of follow‐up (Table S1). Similar findings were also seen when PA was modeled continuously, with a significant inverse association present among all high‐risk subgroups (P≤0.01), except for those with ASCVD (HR per 1‐SD, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.86–1.04). We found no significant interactions of continuously modeled PA with age, sex, or race on the outcome of HF among patients with or without ASCVD. Given the appearance of a possible U‐shaped association between PA and HF among patients with ASCVD in our categorical analysis, we constructed restricted cubic spline models to assess for deviations from linearity in the PA and HF association. We found a near‐linear inverse association between increasing PA and incident HF among patients without ASCVD, and a linear nonsignificant association between PA and HF among patients with ASCVD (Figure S1).

We performed additional analyses to further evaluate the relationship of PA with incident HF among patients with ASCVD. We examined the baseline characteristics of the study population according to ASCVD status and PA category, as displayed in Table S2. Among patients with prevalent ASCVD at visit 1, patients performing recommended versus poor levels of PA were older, less likely to be of black race, and had an overall healthier cardiovascular risk profile with lower body mass index, less current smoking and alcohol use, and a lower prevalence of diabetes mellitus. However, a higher prevalence of antihypertensive medication use and lower high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol were seen among participants with recommended versus poor activity. Recommended PA was associated with a lower prevalence of elevated high‐sensitivity cardiac troponin T among patients without ASCVD (P<0.01) but not among patients with ASCVD (P=0.44). Recommended PA was also associated with a lower prevalence of elevated N‐terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide among patients without ASCVD (P=0.01), but with a trend towards a higher proportion with elevated N‐terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide among patients with ASCVD (P=0.07).

In Cox regression analyses focused on the subgroup with prevalent CHD at visit 1 (instead of all participants with ASCVD), we found similar results as in the primary analysis, with no significant inverse association between higher levels of PA and incident HF (HR for recommended versus poor activity, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.69–1.20) (Table S3).

We also explored the associations of PA with incident CHD and HF following ischemic events. Compared with participants who reported poor PA, those with recommended PA had a significantly lower risk of incident CHD (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.72–0.86). In analyses evaluating the association of higher categories of PA with incident HF with consideration of CHD as a time‐varying covariate (Table 4), we found that recommended PA at baseline was associated with lower HF risk among patients without incident CHD events (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.67–0.83) but not among patients who did have CHD events (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.78–1.04), with a significant interaction between PA category and time‐varying CHD (P for interaction=0.04).

Table 4.

Adjusted HRs and 95% CI for Incident HF Associated With Higher Category of PA Among Participants With a High‐Risk Characteristic, Stratified According to Time‐Varying CHDa

| PA Category | P for Interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Intermediate | Recommended | ||

| No CHD (n=11 317) | Reference (1) | 0.86 (0.77–0.96) | 0.75 (0.67–0.83) | 0.04 |

| Incident CHD after visit 1 (n=2493) | Reference (1) | 0.88 (0.74–1.05) | 0.90 (0.78–1.04) | |

CHD indicates coronary heart disease; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratios; and PA, physical activity.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

When using visit 3 as the baseline for incident HF events and considering cross‐categories of PA at visits 1 and 3, we found that among patients without prevalent ASCVD, compared with patients with persistently poor PA, those with recommended PA at both visits had a significantly lower risk of HF (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.60–0.79). There was a nonsignificant association of persistently recommended levels of PA with incident HF among patients with prevalent ASCVD (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.53–1.06) (Table S4).

Discussion

In the current analysis of the ARIC study we found that higher levels of PA were associated with less incident HF in the overall study sample and among the high‐risk subgroups of hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome. However, the majority of individuals within each of these high‐risk subgroups did not meet recommended levels of PA. We did not find an association between recommended PA and lower HF risk among patients with existing ASCVD. Additionally, there was a significant interaction between PA and ASCVD on incident HF, suggesting PA may have a weaker association with HF risk among patients with versus patients without prevalent ASCVD.

While recommended PA was associated with a lower risk of incident CHD, it was not associated with a reduced risk of future HF among patients who experienced incident CHD events. Overall, our study demonstrates that PA is broadly associated with a lower likelihood of incident HF in most high‐risk subgroups, although most high‐risk individuals do not engage in recommended PA. While PA is associated with reduced risk of incident CHD, it may be less protective against HF once ASCVD is already established.

Current ACCF/AHA guidelines identify subgroups at high risk for developing HF and generally recommend adherence to a heart‐healthy lifestyle, including engaging in regular PA, for reducing HF risk.6 While several studies have demonstrated an association between higher PA and lower HF risk in the general population,8 there are limited data regarding this association in high‐risk subgroups and particularly among patients with ASCVD. An analysis of postmenopausal women in the WHI (Women's Health Initiative) similarly indicated that higher levels of PA may be associated with less HF risk reduction among patients with prevalent CHD, compared with those without CHD.17 Although several clinical trials have demonstrated a benefit of exercise‐based cardiac rehabilitation in reducing the risk of cardiovascular death and rehospitalization among patients with CHD, to date no study has assessed whether exercise‐based cardiac rehabilitation postmyocardial infarction is effective in reducing the risk of developing HF.18, 19 This analysis extends prior research by demonstrating within a diverse population of men and women, inverse associations of PA with long‐term HF in most high‐risk subgroups, with, however, little associations among patients with existing ischemic heart disease.

Different mechanisms underlie the associations of ASCVD, hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome with HF. PA may help to reverse several of the processes leading to HF among patients with hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and the metabolic syndrome. Among patients with hypertension, in addition to lowering BP, PA is associated with favorable cardiac remodeling, with prevention or regression of left ventricular hypertrophy.20, 21 PA also has beneficial effects on metabolic profiles though improvements in insulin resistance, glucose homeostasis, and reductions in weight,22 all of which contribute to the development of HF among patients with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome. Obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension are strongly associated with subclinical myocardial damage as assessed by elevated levels of high‐sensitivity cardiac troponin T, a potent predictor of future HF, and prior data suggest that regular PA is independently associated with lower high‐sensitivity troponin T levels.9, 10 Additional potential mechanisms by which PA may reduce HF risk include reductions in ectopic fat deposition and systemic inflammation.23

While cardiometabolic diseases and hypertension are frequently associated with HF with preserved ejection fraction,24, 25, 26 several studies have demonstrated stronger associations of CHD with HF with reduced ejection fraction than HF with preserved ejection fraction. ASCVD principally leads to HF through ischemic injury and myocyte death, resulting in a lower number of functional myocytes, more replacement fibrosis, and related systolic dysfunction, which may in part be irreversible.27, 28, 29 Although in the current study we did not have the data available to investigate the associations of PA with HF with preserved ejection fraction and HF with reduced ejection fraction, our results are consistent with data of recent studies that demonstrate a stronger inverse association of PA with HF with preserved ejection fraction, and modest or no association between PA and HF with reduced ejection fraction.30, 31

While we did not find a statistically significant inverse association between PA and HF risk among patients with ASCVD, there is a large body of literature demonstrating its beneficial associations with several health outcomes among patients with established vascular disease, including improvements in traditional CVD risk factors and reduced risk of recurrent ASCVD events.32, 33 Additionally, regular PA among patients with ASCVD is associated with improved survival.18, 34 Therefore, there are a myriad of reasons to recommend and promote PA among patients with existing ASCVD, even if it is less effective for HF risk reduction. In our study, analyses incorporating PA levels over a 6‐year period demonstrated a slight tendency towards lower HF risk with persistently high PA among those with ASCVD, potentially indicating that high levels of activity over prolonged periods could lead to some HF risk reduction in this subgroup.

Our findings have important implications for clinical practice. Prevention of risk factors through a healthy lifestyle, including regular PA, is the ideal approach. Among most of the high‐risk subgroups, we found consistent inverse associations between PA and lower HF risk; however, the majority of individuals in each of these subgroups were not achieving recommended PA levels. This highlights the need for multilevel and multidisciplinary interventions to assess and promote regular PA, particularly in high‐risk populations.35, 36 PA should be strongly promoted among patients with ASCVD for a myriad of reasons. However, given the potentially weaker associations with incident HF in this subgroup, additional evidence‐based strategies, such as initiation of β‐blockers and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, particularly in the setting of structural heart disease, should also be considered.37

Study Limitations

It is important to highlight some of our study limitations. Given its observational nature there is the potential for residual and unmeasured confounding. PA was assessed via a questionnaire with possible reporting error, and only measured at 2 time points. It is possible that the presence of ASCVD before the assessment of PA may have influenced reporting of PA. Additionally, the directionality of the associations between PA and prevalent ASCVD are unknown; however, analyses using incident CHD events did not have this limitation and demonstrated similar findings. While prevalent ASCVD at baseline was defined in part on the basis of self‐reported data, our findings were similar in time‐varying analyses where PA was assessed before incident CHD events. The group with ASCVD at visit 1 was the smallest high‐risk subgroup, but analyses incorporating incident adjudicated CHD events provided a significantly larger sample and showed similar results.

It is also possible that among individuals with ASCVD certain high‐risk characteristics influenced PA and thereby affected our results, although we did not consistently find more adverse risk profiles among individuals with ASCVD who engaged in higher PA levels. We also cannot exclude the possibility that premature mortality among patients with ASCVD affected the relationship between PA and HF. Additionally, the use of HF discharge codes for ascertainment of HF events could have led to case misclassification, although this would be consistent across all of the subgroups studied. Furthermore, this analysis did not account for the use of medical therapies or later PA patterns that could have influenced the risk of HF.

Study Strengths

Our study has several strengths including the use of a large, prospective, predominantly biracial, community cohort of middle‐aged adults that has been well characterized with direct measurement of several cardiovascular risk factors, allowing reliable categorization of patients with high‐risk conditions. Additionally, this analysis utilizes extended follow‐up with a large number of HF events that allowed for stratification by key characteristics and multiple sensitivity analyses. Regardless, clinical trials would ultimately be needed to prove that PA reduces HF risk in most high‐risk subgroups.

Conclusions

In the current analyses of the ARIC study we found that higher PA is associated with lower HF risk among several subgroups known to be at high risk for HF, including patients with hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome. However, while PA is associated with reduced ASCVD risk and has multiple established cardioprotective benefits for patients with ischemic heart disease, it may be less effective in preventing HF once ASCVD is already established.

Sources of Funding

The ARIC study has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI); the National Institutes of Health (NIH); and the Department of Health and Human Services, under contract numbers HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700005I, and HHSN268201700004I. Dr Selvin was supported by NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants K24DK106414 and R01DK089174. Dr Ndumele was supported by NIH/NHLBI grants K23 HL12247 and R01 HL146907, and by AHA grant 20SFRN35120152.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S4 Figure S1

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014885 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014885.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

See Editorial by Pandey and Kitzman

References

- 1. McCullough PA, Philbin EF, Spertus JA, Kaatz S, Sandberg KR, Weaver WD; Resource Utilization Among Congestive Heart Failure (REACH) Study . Confirmation of a heart failure epidemic: findings from the Resource Utilization Among Congestive Heart Failure (REACH) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheng RK, Cox M, Neely ML, Heidenreich PA, Bhatt DL, Eapen ZJ, Hernandez AF, Butler J, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction in the Medicare population. Am Heart J. 2014;168:721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shah KS, Xu H, Matsouaka RA, Bhatt DL, Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, Devore AD, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5‐year outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2476–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schocken DD, Benjamin EJ, Fonarow GC, Krumholz HM, Levy D, Mensah GA, Narula J, Shor ES, Young JB, Hong Y, et al. Prevention of heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Epidemiology and Prevention, Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, and High Blood Pressure Research; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2008;117:2544–2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Writing Committee Members , Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. He J, Ogden LG, Bazzano LA, Vupputuri S, Loria C, Whelton PK. Risk factors for congestive heart failure in US men and women: NHANES I epidemiologic follow‐up study. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pandey A, Garg S, Khunger M, Darden D, Ayers C, Kumbhani DJ, Mayo HG, de Lemos JA, Berry JD. Dose‐response relationship between physical activity and risk of heart failure: a meta‐analysis. Circulation. 2015;132:1786–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ndumele CE, Coresh J, Lazo M, Hoogeveen RC, Blumenthal RS, Folsom AR, Selvin E, Ballantyne CM, Nambi V. Obesity, subclinical myocardial injury, and incident heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:600–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Florido R, Ndumele CE, Kwak L, Pang Y, Matsushita K, Schrack JA, Lazo M, Nambi V, Blumenthal RS, Folsom AR, et al. Physical activity, obesity, and subclinical myocardial damage. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Richardson MT, Ainsworth BE, Wu HC, Jacobs DR Jr, Leon AS. Ability of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC)/Baecke Questionnaire to assess leisure‐time physical activity. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR Jr, Tudor‐Locke C, Greer JL, Vezina J, Whitt‐Glover MC, Leon AS. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, Nieman DC, Swain DP; American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand . Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1334–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, George SM, Olson RD. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018;138:e426–e483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. LaMonte MJ, Manson JE, Chomistek AK, Larson JC, Lewis CE, Bea JW, Johnson KC, Li W, Klein L, LaCroix AZ, et al. Physical activity and incidence of heart failure in postmenopausal women. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:983–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, Taylor RS. Exercise‐based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. West RR, Jones DA, Henderson AH. Rehabilitation after myocardial infarction trial (RAMIT): multi‐centre randomised controlled trial of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation in patients following acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2012;98:637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hegde SM, Solomon SD. Influence of physical activity on hypertension and cardiac structure and function. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kokkinos PF, Narayan P, Colleran JA, Pittaras A, Notargiacomo A, Reda D, Papademetriou V. Effects of regular exercise on blood pressure and left ventricular hypertrophy in African‐American men with severe hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1462–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aune D, Norat T, Leitzmann M, Tonstad S, Vatten LJ. Physical activity and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose‐response meta‐analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30:529–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vella CA, Allison MA, Cushman M, Jenny NS, Miles MP, Larsen B, Lakoski SG, Michos ED, Blaha MJ. Physical activity and adiposity‐related inflammation: the MESA. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49:915–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wilner B, Garg S, Ayers CR, Maroules CD, McColl R, Matulevicius SA, de Lemos JA, Drazner MH, Peshock R, Neeland IJ. Dynamic relation of changes in weight and indices of fat distribution with cardiac structure and function: the Dallas Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005897 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kalogeropoulos A, Georgiopoulou V, Psaty BM, Rodondi N, Smith AL, Harrison DG, Liu Y, Hoffmann U, Bauer DC, Newman AB, et al. Inflammatory markers and incident heart failure risk in older adults: the Health ABC (Health, Aging, and Body Composition) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2129–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glezeva N, Baugh JA. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and its potential as a therapeutic target. Heart Fail Rev. 2014;19:681–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ho JE, Lyass A, Lee DS, Vasan RS, Kannel WB, Larson MG, Levy D. Predictors of new‐onset heart failure: differences in preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:279–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee DS, Gona P, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Wang TJ, Tu JV, Levy D. Relation of disease pathogenesis and risk factors to heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction: insights from the Framingham Heart Study of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2009;119:3070–3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ather S, Chan W, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Ramasubbu K, Zachariah AA, Wehrens XH, Deswal A. Impact of noncardiac comorbidities on morbidity and mortality in a predominantly male population with heart failure and preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:998–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kraigher‐Krainer E, Lyass A, Massaro JM, Lee DS, Ho JE, Levy D, Kannel WB, Vasan RS. Association of physical activity and heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction in the elderly: the Framingham Heart Study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:742–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pandey A, LaMonte M, Klein L, Ayers C, Psaty BM, Eaton CB, Allen NB, de Lemos JA, Carnethon M, Greenland P, et al. Relationship between physical activity, body mass index, and risk of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1129–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lavie CJ, Arena R, Swift DL, Johannsen NM, Sui X, Lee DC, Earnest CP, Church TS, O'Keefe JH, Milani RV, et al. Exercise and the cardiovascular system: clinical science and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Res. 2015;117:207–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sattelmair J, Pertman J, Ding EL, Kohl HW III, Haskell W, Lee IM. Dose response between physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta‐analysis. Circulation. 2011;124:789–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stewart RAH, Held C, Hadziosmanovic N, Armstrong PW, Cannon CP, Granger CB, Hagström E, Hochman JS, Koenig W, Lonn E, et al. Physical activity and mortality in patients with stable coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1689–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. AuYoung M, Linke SE, Pagoto S, Buman MP, Craft LL, Richardson CR, Hutber A, Marcus BH, Estabrooks P, Sheinfeld Gorin S. Integrating physical activity in primary care practice. Am J Med. 2016;129:1022–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grandes G, Sanchez A, Sanchez‐Pinilla RO, Torcal J, Montoya I, Lizarraga K, Serra J; PEPAF Group . Effectiveness of physical activity advice and prescription by physicians in routine primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bahit MC, Kochar A, Granger CB. Post‐myocardial infarction heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S4 Figure S1