We deeply sequenced two pairs of widely used infectious clones (4 plasmids) of the bipartite begomoviruses African cassava mosaic virus (ACMV) and East African cassava mosaic Cameroon virus (EACMCV). The ACMV clones were quite divergent from published sequences. Raw reads, consensus plasmid sequences, and the infectious clones themselves are all publicly available.

ABSTRACT

We deeply sequenced two pairs of widely used infectious clones (4 plasmids) of the bipartite begomoviruses African cassava mosaic virus (ACMV) and East African cassava mosaic Cameroon virus (EACMCV). The ACMV clones were quite divergent from published sequences. Raw reads, consensus plasmid sequences, and the infectious clones themselves are all publicly available.

ANNOUNCEMENT

Infectious clones are a central tool of molecular virology. Circular single-stranded DNA viruses such as begomoviruses are often cloned in a two-step process to create partial tandem dimers containing two copies of the virus origin of replication, a configuration that enhances infection (1). Cloned isolates of African cassava mosaic virus (ACMV) and East African cassava mosaic Cameroon virus (EACMCV) provided conclusive proof of synergy between two major clades of cassava begomoviruses (2), which is a defining feature of the epidemic of mosaic disease that has devastated cassava production in sub-Saharan Africa (3, 4). Here, we announce new sequence resources for these frequently used clones, which confirm the EACMCV clones and clarify the identity of the ACMV clones.

Complete and accurate plasmid sequences considerably simplify the molecular analysis of infectious clones and the design of new constructs. To confirm the sequences of the four plasmids listed in Table 1, we grew transformed Escherichia coli DH5α cultures overnight at 37°C with ampicillin selection and purified each plasmid with the Qiagen plasmid maxi kit. Libraries were prepared from Covaris-sheared plasmid DNA in triplicate with the NEBNext Ultra II kit and sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 500 platform in the 150-bp paired-end read configuration.

TABLE 1.

GenBank and Addgene identifiers for the four previously described infectious clones and corresponding virus (monomer) sequencesa

| Virus segment | Data for viruses |

Data for plasmids |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GenBank accession no. | Segment length (nt)b | G+C content (%) | GenBank accession no. | SRA accession no. | Addgene ID | |

| ACMV DNA-Ac | MT858793 | 2,781 | 44.7 | MT856193 | SRX8853831 | 159134 |

| SRX8853832 | ||||||

| SRX8853835 | ||||||

| ACMV DNA-Bd | MT858794 | 2,725 | 40.8 | MT856194 | SRX8853836 | 159135 |

| SRX8853837 | ||||||

| SRX8853838 | ||||||

| EACMCV DNA-Ae | AF112354 | 2,800 | 45.1 | MT856195 | SRX8853839 | 159136 |

| SRX8853840 | ||||||

| SRX8853841 | ||||||

| EACMCV DNA-Bf | FJ826890 | 2,732 | 44.1 | MT856192 | SRX8853833 | 159137 |

| SRX8853834 | ||||||

| SRX8853842 | ||||||

These plasmids have been described (2, 5, 6) but not fully sequenced, so we deduced sequence maps (including partial tandem dimer virus segment inserts) based on the restriction sites used for cloning. Reads were trimmed with Cutadapt v1.16 (7) and aligned to these sequences, listed in Table 1, with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner MEM algorithm (BWA-MEM) v0.7.13 (8). Variants relative to each reference sequence were identified with SAMtools v1.8 (9) and VarScan v2.4.4 (10). We corrected each plasmid sequence and aligned reads to it a second time.

The EACMCV DNA-A and DNA-B clones had four and two single-nucleotide differences, respectively, relative to their corresponding sequences in GenBank (accession numbers AF112354.1 and FJ826890.1, respectively). Relative to the new sequences (in the standard coordinate system starting from the virus replication origin nick site), these differences were T139A, G161R, T181TC, and A206AC for DNA-A and T1671G and A2724AT for DNA-B. The consensus sequences of the ACMV clones, however, were 3.1% and 5.8% divergent from the sequences (GenBank accession numbers AF112352.1 and AF112353.1) originally reported by Fondong et al. (2), as calculated with Sequence Demarcation Tool v1.2 (11). This difference was not entirely unexpected, because of the parallel history of two sets of ACMV clones; infectious partial tandem dimer clones were made via restriction digestion/ligation from sap-inoculated Nicotiana benthamiana plants, whereas the monomer segment unit clones were cloned with PCR from the same original cassava field sample (2). We expect that these complete infectious clone sequences will be of great utility to the community, given that many follow-up publications (12–23) specifically referenced the related but nonidentical monomer sequences (AF112352.1 and AF112353.1).

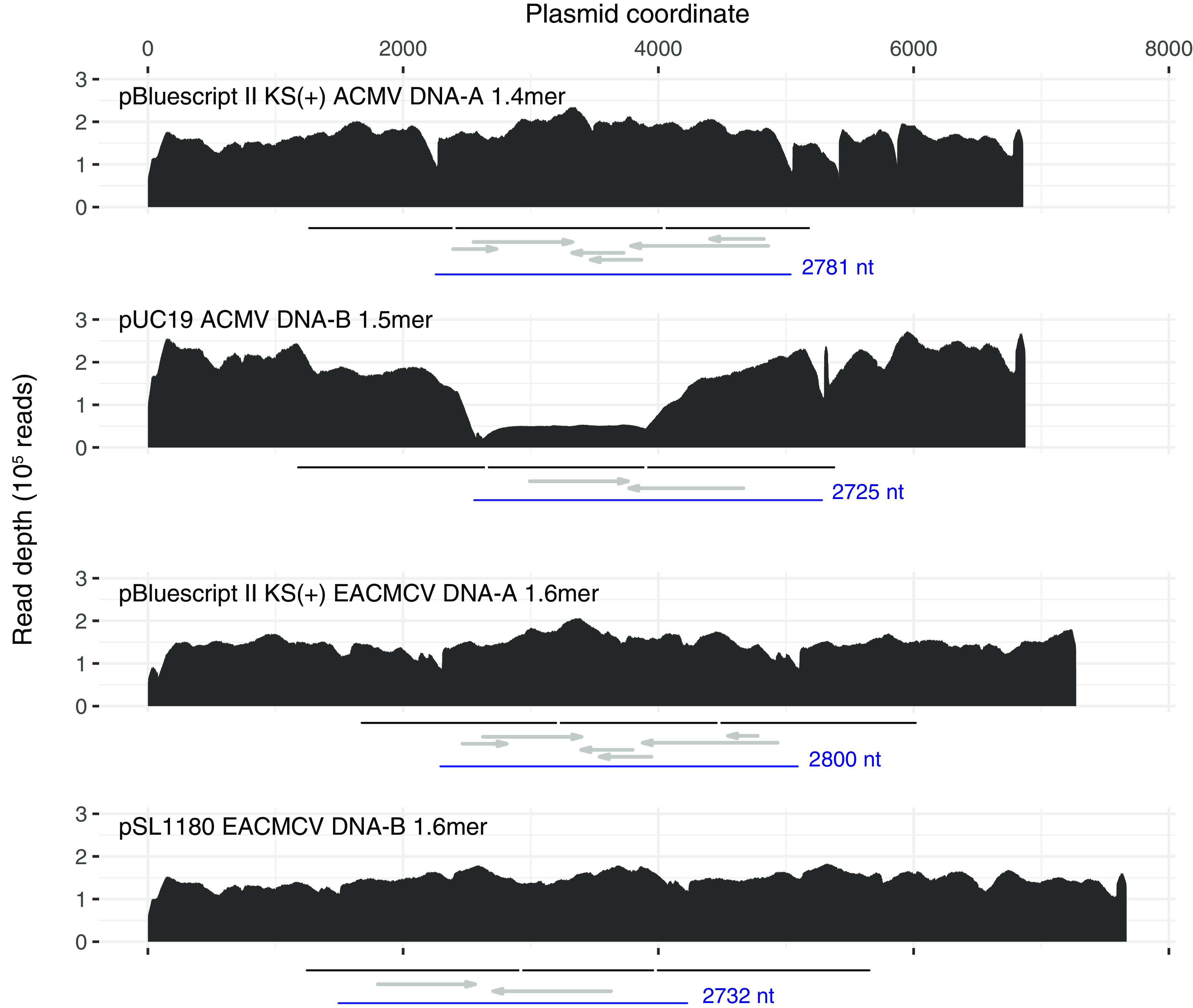

We obtained deep coverage, over 18,000-fold across all positions for all four plasmids, with an average of 157,000-fold coverage (Fig. 1). This read depth was consistent across three separate libraries for each plasmid and ensures the correctness of the partial tandem dimer sequences. Our results underscore the value of confirming the sequences of molecular clones.

FIG 1.

Plots of Illumina read depth across the length of the four infectious clone plasmids. One of three libraries is shown for each plasmid (Sequence Read Archive accession numbers SRR12354432, SRR12354427, SRR12354424, and SRR12354421). The region in each plasmid corresponding to each virus segment partial tandem dimer unit is indicated with a black line under each graph. Vertical white lines demarcate the boundaries of the unique and duplicated regions of each concatemer. Each virus segment monomer unit (between two replication origin nick sites) is shown in blue. Canonical virus genes are indicated with gray arrows, left to right for virus sense (AV1, AV2, and BV1) and right to left for complementary sense (AC1 to AC4 and BC1). The uneven read depth for the ACMV DNA-B plasmid is due to instability (truncation), which is evident in single-cut restriction digests (not shown). Such partial deletion of tandem duplicated regions in E. coli is not uncommon (24).

Data availability.

Plasmids are available from Addgene, and sequences for full plasmids and ACMV segments are available in GenBank (Table 1). The raw Illumina data are available from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA649777; Table 1). Data processing code has been archived as Zenodo record 4075362 (https://zenodo.org/record/4118067).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NSF award OIA-1545553 to L.H.-B. and S.D.

We thank the NC State University Genomic Sciences Laboratory (Raleigh, NC, USA) for excellent sequencing services. We thank the staff of the Office of Advanced Research Computing (OARC) at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, for access to and maintenance of the Amarel cluster. We thank Getu Beyene (Donald Danforth Plant Science Center) for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stenger DC, Revington GN, Stevenson MC, Bisaro DM. 1991. Replicational release of geminivirus genomes from tandemly repeated copies: evidence for rolling-circle replication of a plant viral DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:8029–8033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.8029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fondong VN, Pita JS, Rey MEC, de Kochko A, Beachy RN, Fauquet CM. 2000. Evidence of synergism between African cassava mosaic virus and a new double-recombinant geminivirus infecting cassava in Cameroon. J Gen Virol 81:287–297. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-1-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pita JS, Fondong VN, Sangaré A, Otim-Nape GW, Ogwal S, Fauquet CM. 2001. Recombination, pseudorecombination and synergism of geminiviruses are determinant keys to the epidemic of severe cassava mosaic disease in Uganda. J Gen Virol 82:655–665. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-3-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mbewe W, Hanley-Bowdoin L, Ndunguru J, Duffy S. 2020. Cassava viruses: epidemiology, evolution, and management, p 133–157. In Ristaino JB, Records A (ed), Emerging plant diseases and global food security. The American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, MN. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fondong VN, Chen K. 2011. Genetic variability of East African cassava mosaic Cameroon virus under field and controlled environment conditions. Virology 413:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chowda Reddy RV, Dong W, Njock T, Rey MEC, Fondong VN. 2012. Molecular interaction between two cassava geminiviruses exhibiting cross-protection. Virus Res 163:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin M. 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. Embnet J 17:10–12. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H. 2013. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv:13033997 [q-bio] https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997.

- 9.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup . 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. 2012. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res 22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muhire BM, Varsani A, Martin DP. 2014. SDT: a virus classification tool based on pairwise sequence alignment and identity calculation. PLoS ONE 9:e108277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanitharani R, Chellappan P, Fauquet CM. 2003. Short interfering RNA-mediated interference of gene expression and viral DNA accumulation in cultured plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:9632–9636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733874100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanitharani R, Chellappan P, Pita JS, Fauquet CM. 2004. Differential roles of AC2 and AC4 of cassava geminiviruses in mediating synergism and suppression of posttranscriptional gene silencing. J Virol 78:9487–9498. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9487-9498.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chellappan P, Vanitharani R, Pita J, Fauquet CM. 2004. Short interfering RNA accumulation correlates with host recovery in DNA virus-infected hosts, and gene silencing targets specific viral sequences. J Virol 78:7465–7477. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7465-7477.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chellappan P, Vanitharani R, Fauquet CM. 2005. MicroRNA-binding viral protein interferes with Arabidopsis development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:10381–10386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504439102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chellappan P, Vanitharani R, Ogbe F, Fauquet CM. 2005. Effect of temperature on geminivirus-induced RNA silencing in plants. Plant Physiol 138:1828–1841. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.066563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin I, Patil BL, Briddon RW, Mansoor S, Fauquet CM. 2011. A common set of developmental miRNAs are upregulated in Nicotiana benthamiana by diverse begomoviruses. Virol J 8:143. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reyes MI, Nash TE, Dallas MM, Ascencio-Ibáñez JT, Hanley-Bowdoin L. 2013. Peptide aptamers that bind to geminivirus replication proteins confer a resistance phenotype to tomato yellow leaf curl virus and tomato mottle virus infection in tomato. J Virol 87:9691–9706. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01095-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ndunguru J, León LD, Doyle CD, Sseruwagi P, Plata G, Legg JP, Thompson G, Tohme J, Aveling T, Ascencio-Ibáñez JT, Hanley-Bowdoin L. 2016. Two novel DNAs that enhance symptoms and overcome CMD2 resistance to cassava mosaic disease. J Virol 90:4160–4173. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02834-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patil BL, Bagewadi B, Yadav JS, Fauquet CM. 2016. Mapping and identification of cassava mosaic geminivirus DNA-A and DNA-B genome sequences for efficient siRNA expression and RNAi based virus resistance by transient agro-infiltration studies. Virus Res 213:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beyene G, Chauhan RD, Wagaba H, Moll T, Alicai T, Miano D, Carrington JC, Taylor NJ. 2016. Loss of CMD2-mediated resistance to cassava mosaic disease in plants regenerated through somatic embryogenesis. Mol Plant Pathol 17:1095–1110. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuria P, Ilyas M, Ateka E, Miano D, Onguso J, Carrington JC, Taylor NJ. 2017. Differential response of cassava genotypes to infection by cassava mosaic geminiviruses. Virus Res 227:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chauhan RD, Beyene G, Taylor NJ. 2018. Multiple morphogenic culture systems cause loss of resistance to cassava mosaic disease. BMC Plant Biol 18:132. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1354-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveira PH, Prather KJ, Prazeres DMF, Monteiro GA. 2009. Structural instability of plasmid biopharmaceuticals: challenges and implications. Trends Biotechnol 27:503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Plasmids are available from Addgene, and sequences for full plasmids and ACMV segments are available in GenBank (Table 1). The raw Illumina data are available from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA649777; Table 1). Data processing code has been archived as Zenodo record 4075362 (https://zenodo.org/record/4118067).