SUMMARY:

The middle meningeal artery is the major human dural artery. Its origin and course can vary a great deal in relation, not only with the embryologic development of the hyostapedial system, but also because of the relationship of this system with the ICA, ophthalmic artery, trigeminal artery, and inferolateral trunk. After summarizing these systems in the first part our review, our purpose is to describe, in this second part, the anatomy, the possible origins, and courses of the middle meningeal artery. This review is enriched by the correlation of each variant to the related embryologic explanation as well as by some clinical cases shown in the figures. We discuss, in conclusion, some clinical conditions that require detailed knowledge of possible variants of the middle meningeal artery.

The middle meningeal artery (MMA) is one of the largest branches of the external carotid artery and the most important dural artery because it supplies more than two-thirds of the cranial dura.1 However, the most interesting aspects of this artery are not its size or its clinical importance but its embryologic development and its numerous anatomic variations. An understanding of the anatomy and variants of the MMA provides a good knowledge and understanding of the hyostapedial system and of the vascular anatomy of the middle ear. The aim of this article is to summarize, through a narrative review based on the literature and clinical examples, the possible anatomic variations of the MMA. Each variant will be related to its embryologic explication, which we treated in detail in part 1 of this article. The knowledge of these variants is important especially for neuroradiologists to treat dural pathologies and also for surgeons who approach the middle ear pathologies.

Origin of the Artery

In almost all cases, the MMA arises from the internal maxillary artery (IMA), but it could also originate from the ICA or, more surprisingly, from the basilar artery. Possible origins of the MMA are listed in Table 1, with their respective embryologic explanation. The detailed description of the MMA embryologic development was analyzed in part 1 of our article.

Table 1:

Different origin of the MMA with modifications associated and embryologic explanation

| Variations in the Origin of the MMA |

Embryologic Implications |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Associated Changes | Embryologic Explanation | Embryo Size (mm) |

| IMA origin | Normal anatomy | Normal embryology | |

| Basilar artery origin | Absence foramen spinosum | Anastomosis between SA and trigeminal artery; anastomosis between SA and lateral pontine artery | 12 |

| Cavernous ICA origin | Absence foramen spinosum | Anastomosis between inferolateral trunk and SA | 16 |

| Partial persistent SA | Absence foramen spinosum; enlargement of the facial canal | Regression of the proximal part of the maxillomandibular branch; persistence of the intratympanic segment of the SA | 24 |

| Complete persistent SA | Enlargement of the facial canal | Lack of annexation of the maxillomandibular branch by the ventral pharyngeal artery; persistence of the intratympanic segment of the SA | 24 |

| Pseudopetrous ICA origin | Absence foramen spinosum; enlargement of the facial canal; absence of the exocranial opening of the carotid canal | Agenesis of the first and second segments of the ICA; intratympanic anastomosis between inferior tympanic and caroticotympanic arteries; persistence of the intratympanic segment of the SA | 4–5; 24 |

| Cervical ICA origin | Absence foramen spinosum; enlargement of the facial canal | Intratympanic anastomosis between inferior and superior tympanic arteries; regression of the proximal part of the maxillomandibular branch; persistence of the intratympanic segment of the SA | 16; 24 |

| Occipital artery origin | Absence foramen spinosum; enlargement of the facial canal | No clear explanation | |

| Distal petrous ICA origin | Absence foramen spinosum | Lack of annexation of the mandibular artery (first aortic arch) by the SA (second aortic arch) | 9 |

IMA Origin.

The classic origin of the MMA is usually described on the first segment of the IMA into the infratemporal fossa, just behind the condylar process of the mandible.1,2 The MMA is the largest and usually the first ascending branch of the IMA,2 but it could also have a common trunk with the accessory meningeal artery, depending on the position of the IMA course with regard to the external pterygoid muscle.3 When the IMA passes superficially to the muscle, the MMA and accessory meningeal artery have a common origin from the IMA, and the inferior dental and posterior deep temporal arteries have a separate origin. On the contrary, when the IMA passes deep to the external pterygoid muscle, the MMA, and the accessory meningeal artery have distinct origins from the IMA, and the inferior dental and the posterior deep temporal arteries share a common trunk.2

Low4 described an interesting cadaveric case of distal (third segment) IMA origin of the MMA. In his study, he inspected the osseous grooves of the skull and noted that, associated with the absence of the foramen spinosum, the osseous grooves of the MMA converge to the superior orbital fissure.4 He concluded that the MMA takes its origin in the pterygoid fossa from the distal IMA and passes through the inferior and superior orbital fissures.4 Probably, in his description, he misinterpreted an ophthalmic artery (OA) origin of the MMA, not already known at its publication.3

Basilar Artery Origin.

Altmann5 was the first investigator to describe a case of basilar artery origin of the MMA in his monumental article about anomalies of the carotid system but failed to give clear embryologic explanation of the anatomic variation. Surprisingly, he described the origin of the artery between the AICA and PICA, and its course as “accompanying the acoustic-facial nerve,” passing through the internal acoustic canal to reach the superior branch of the stapedial artery (SA). After this initial description, <10 cases of basilar artery origin of the MMA were successively published.6-12 Usually, the MMA originates from the distal third of the basilar artery between the superior cerebellar artery and the AICA. It courses anteriorly along the trigeminal nerve to reach the gasserian region, where it anastomoses with the petrosal branch of the MMA. Usually, only the posterior (parieto-occipital) branch of the MMA arises from the basilar artery and the anterior (frontal) branch keeps its normal origin from the IMA6,9-11,13; however, in a few cases,6,8,12 the complete territory of the MMA had a basilar artery origin.

Two distinct embryologic explanations are postulated by investigators to explain this anatomic variation. Seeger and Hemmer6 and Lasjaunias et al3,7 explained it by an anastomosis in the gasserian region between the basilar remnant of the trigeminal artery and the persistent SA. Consequently, after regression of the proximal stem of the SA at the level of the stapes, the MMA takes its origin from the basilar artery. Other investigators postulated that an enlarged lateral pontine artery develops during the embryologic life and anastomoses with the SA.8,9,14 A rare case of MMA origin from an enlarged pontine artery is presented in Fig 1. Kuruvilla et al10 described a particular case in which the MMA arose directly from the PICA and not from the basilar artery. No embryologic explanation was found to explain such an origin.

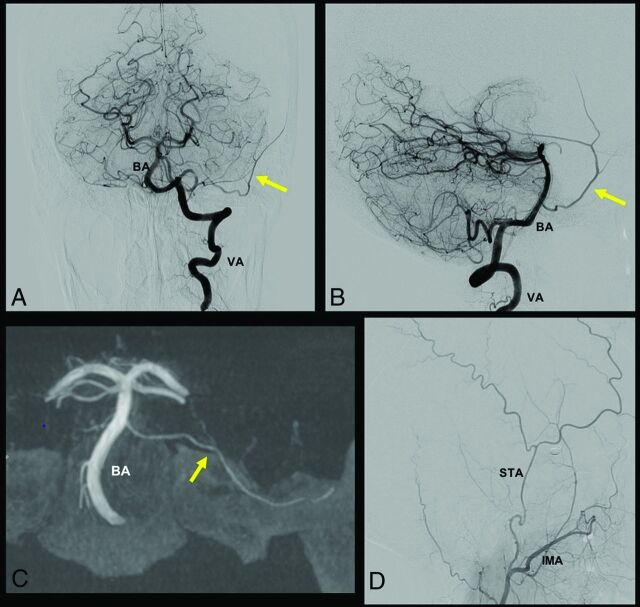

FIG 1.

A case of MMA origin from basilar artery (BA) pontine perforating branch. In this case, the MMA originates from a pontine branch of the BA, as indicated by the yellow arrow in A, B, and C. A and B, A frontal and lateral view of left vertebral artery (VA) injection, respectively. C, A frontal XperCT (Philips Healthcare) reconstruction with the same MMA origin. D, A distal external carotid artery injection, where the superficial temporal artery (STA) and the IMA are visible, without the typical MMA origin from the IMA.

OA Origin.

The MMA could also originate from the OA instead of the IMA. The incidence of this vascular variation is estimated to be 0.5% by Dilenge and Ascherl,15 based on a large angiographic series. Few cases of MMA that arose from the OA are described in the literature.7,16-24 The first case was presented by Curnow25 and, in the same period, Meyer26 also cited 4 cadaveric cases originally described by Zuckerkandl in 1876,27 during a congress presentation. This vascular anomaly is considered as the consequence of 2 different embryologic processes.7 The first is the failure of the supraorbital branch (SA) to regress. The second is the absence of anastomosis between the maxillomandibular branch of the SA and the IMA.28 Consequently, the MMA origins from the OA passing through the lateral part of the superior orbital fissure and the foramen spinosum are usually absent.

Maiuri et al29 proposed 3 different types of this vascular variation, as highlighted in Table 2. The first type is the complete MMA territory taken over by the OA through the superficial recurrent OA. The second type is only the anterior branch of the MMA with an OA origin; the posterior branch of the MMA keeps its origin from the IMA. The third type is not really an OA origin of the MMA but an anastomosis between the OA and the accessory meningeal artery (through the deep recurrent OA), and, consequently, the anterior meningeal territory is supplied by both the MMA and the OA, without any communication. Two cases of complete and partial origins of the MMA from the OA are reported in Fig 2. It is still a matter of debate if the MMA originates from the OA directly or from the proximal part of the lacrimal artery.28

Table 2:

Different types of OA origin of the MMAa

| Type | Vascular Anatomy | Foramen Spinosum |

|---|---|---|

| I | Complete OA origin of the MMA | Absence |

| II | Partial OA origin of the MMA; anterior division from the OA; posterior division from the IMA | Reduced in size |

| III | OA origin of the accessory meningeal artery | Normal |

From Ref.28

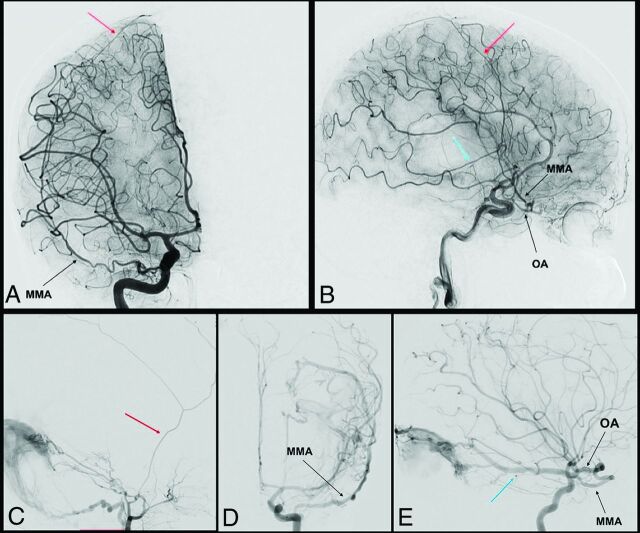

FIG 2.

Complete and partial MMA origin from OA. The anteroposterior and lateral view angiograms (A and B respectively) show a rare case of a complete MMA origin from the OA. The OA, through the superficial recurrent OA, gives origin to the MMA, that passes through the lateral part of the superior orbital fissure, and bifurcates into its anterior (red arrow) and posterior division (blue arrow). In the angiograms C, D, and E, a rare case of a partial origin of the MMA from the OA is shown. D and E, Angiograms of a left ICA injection in the frontal and lateral views, where the posterior branch of the MMA (blue arrow) originates at the OA and feeds a tentorial AVF. After the external carotid artery injection (C), only the anterior branch of the MMA is enhanced (red arrow).

Cavernous ICA Origin.

The lone case of a cavernous ICA origin of the MMA was described by Lasjaunias et al7 in one of their most famous articles that summarized distinct vascular anomalies encountered at the base of the skull. They published, at another time, the same case in their textbook3 to illustrate this very rare anatomic variant. In this case, all branches of the MMA were filled during ICA injection, and its origin arose from the horizontal portion of the cavernous ICA. Lasjaunias et al7 elegantly explained this variation by the anastomosis during embryologic life between the posterior branch of the inferolateral trunk and the SA; consequently, the proximal stem of the MMA regressed (or was not formed) and the foramen spinosum was absent.

Petrous ICA Origin (Complete and Partial Persistence of the SA).

The complete persistence of the SA is a very rare variant, only 2 cases were published in the context of an ICA aneurysm30 or PHACE (posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta/cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities) syndrome.3 In these cases, the SA keeps its embryonic origin from the petrous ICA, passes through the middle ear, and gives it 2 branches: one intracranial, which corresponds to the MMA, and the other extracranial, which leaves the cranial cavity through the foramen spinosum. Consequently, the foramen spinosum is enlarged, the cochlear promontory is eroded, and the IMA arises from the SA instead of the external carotid artery. Such an anatomic variant could easily be explained by the absence of an embryologic annexation of the maxillomandibular branch (of the SA) by the ventral pharyngeal artery, details of which are described in part 1 of our article.

The partial persistence of the SA is more frequent,1,5,7,28,31-36 and, in this case, only the intracranial branch of the SA keeps its origin from the petrous ICA. The foramen spinosum is absent or reduced in size and the MMA arises from the SA instead of the IMA. This variant is explained by the regression of the proximal part of the maxillomandibular artery instead of the proximal part of the SA.3

Pseudopetrous ICA Origin (Persistence of the SA Associated with Aberrant Flow of the ICA).

In rare cases, the persistence of the SA and the consequent origin of the MMA from the petrous ICA are associated with an intratympanic course of the ICA (also known as “aberrant flow of the ICA”).7,14,28,32,37,38 The intratympanic course of the ICA is explained by the agenesis of the first 2 segments of the primitive carotid artery, with a hypertrophied inferior tympanic artery that maintains the anastomosis between the ascendant pharyngeal artery and the caroticotympanic artery (a branch of the ICA) into the tympanic cavity. Therefore, the cervical and intratympanic segments of this artery do not derivate from the carotid system but from the pharyngo-occipital and hyostapedial systems (pseudo-ICA).3,7,28 In these cases, the MMA arises from the ICA in its tympanic segment and passes through the stapes to have the same course described in the previous paragraph. This variant is described in detail in part 1 of our article.

Cervical ICA Origin (Pharyngotympanostapedial Artery).

The MMA could also arise from the cervical segment of the ICA. This very rare variant was first described by Lasjaunias et al7 in their original publication. The same case served as an illustration in the textbook “Surgical Neuroangiography”3 and only 1 similar case was published by Baltsavias et al.39 The MMA arises from the cervical portion of the ICA, ascends along the cervical ICA, enters into the tympanic cavity through the inferior tympanic canal, and follows the usual course of the SA. The 2 cases described were presented as “partial” persistence of the SA, with only the MMA arising from the SA and the absence of the foramen spinosum. In this variant, an annexation of the SA by the inferior tympanic artery (the branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery), with regression of the proximal part of the SA explains this vascular configuration. Therefore, the SA arises from the cervical instead of the petrous segment of the ICA.

Occipital Artery Origin.

Diamond40 described a remarkable case of partial persistent SA found during a temporal bone dissection. The peculiarity of this case was that the SA arose from the occipital artery instead of the petrous ICA passing through a “special foramen” to enter into the petrous part of the temporal bone between the styloid process and the carotid canal. After passing through the posterior wall of the tympanic cavity and through the stapes, the SA entered the facial canal to reach the petrous apex and to give rise to the future branches of the MMA. In this article, Diamond40 did not give a clear embryonic explanation or a hypothesis of the variant he found.

Distal Petrous ICA Origin (Mandibular Artery Origin).

Lasjaunias et al3 were the only investigators to show a case of a distal petrous ICA origin of the MMA near the normal origin of the vidian artery. In this case, the MMA did not follow an intratympanic course.3 The investigators explained this variant by the absence of annexation of the first aortic arch by the second aortic arch (the SA); therefore, the mandibular artery retains its primary territory, which is the MMA territory.3

Course of the Artery

The first extracranial segment of the MMA is from its origin to its entry into the foramen spinosum. The more anterior the origin of the MMA is, the more oblique backward is the extracranial segment. At the level of the foramen spinosum, the artery bends anteriorly and laterally to follow the temporal fossa. This bend is responsible for the characteristic aspect of the MMA on DSA. After its entry into the cranial cavity, the MMA has a lateral course grooving the greater sphenoid wing. Merland et al2 described 3 intracranial segments of the MMA. The first is the temporobasal segment, where the artery follows the temporal fossa and curves upward, where it becomes the second or temporopterional segment. After passing the pterional region, the artery enters in its coronal segment where the artery follows the coronal suture to end at the region of the bregma. Martins et al1 considered the course of the artery shorter and simpler. They described the termination of the MMA, where it divides into anterior and posterior divisions at the pterional region. The anterior division of the MMA is classically the coronal segment previously described by Merland et al.2

Branches of the Artery

The 2 most precise and complete publications that describe the branches of the MMA were published by Merland et al2 and Martins et al.1 One description is based on cerebral angiographies; the other is based on cadaveric dissections. Before these publications, Salamon et al41,42 paid particular attention to correlate the anatomy with the angiographic images. As noted in the previous paragraph, these 2 investigators (Merland and Martins) used a different naming of the branches, even if the terminology used by Martins et al1 seems to be the most comprehensive. Different branches of the MMA with the dural territory associated and possible anastomosis with other dural arteries are shown in Table 3.41

Table 3:

Different branches of the MMA with their respective anastomosis

| MMA Branches | Origin from the MMA | Territory (Dural and Neural) | Possible Anastomosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Petrosal branch | Foramen spinosum | Trigeminal ganglion and nerves; posteromedial floor of the middle fossa; insertion of tentorium (medial half); superior petrosal sinus | Ascending pharyngeal artery (carotid branch); medial and lateral tentorial arteries (ICA) |

| Superior tympanic artery | Petrosal branch | Greater superficial petrosal nerve; geniculate ganglion; tympanic cavity (superior part) | Inferior tympanic artery (ascending pharyngeal artery); caroticotympanic artery (ICA); anterior tympanic artery (IMA); stylomastoid artery (posterior auricular artery) |

| Cavernous branch | Petrosal branch | Lateral wall of the cavernous sinus | Accessory meningeal artery; inferolateral trunk (ICA) |

| Anterior division or frontal branch | Pterional region | Frontal and anterior parietal convexity; superior sagittal sinus; anterior and middle fossa (lateral part) | Anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries (OA); contralateral MMA |

| Falcine arteries | Anterior and posterior division | Falx cerebri | Anterior falcine artery (OA); anterior cerebral artery; posterior meningeal artery (vertebral artery) |

| Medial branch or sphenoidal branch | Anterior division | Lesser sphenoid wing; superior orbital fissure; peri-orbital (lateral) | Recurrent meningeal branches (OA); inferolateral trunk (ICA) |

| Petrosquamosal branch | Posterior division | Posterolateral floor of the middle fossa; insertion of tentorium (lateral half); superior petrosal sinus; transverse and sigmoid sinuses; dura of the posterior fossa (superior part) | Ascending pharyngeal artery (jugular branch); lateral tentorial artery (ICA); occipital artery (mastoid branch) |

| Parieto-occipital branch | Posterior division | Temporosquamous dura; parieto-occipital convexity; superior sagittal sinus | Posterior meningeal artery (vertebral artery) |

The course and branches of MMA are indicated on the DSA, shown in Fig 3. The MMA divides, at the pterional region, into 2 divisions: anterior and posterior. Before its bifurcation, the MMA gives 2 branches that supply the dura of the temporal fossa.2,19,28 The first is the petrosal branch, which courses on the petrous apex and supplies the dura of this region (including the gasserian ganglion) and also the superior part of the tympanic cavity via the superior tympanic artery passing through the facial canal. The second basal branch of the MMA is the cavernous branch, which supply the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus and anastomoses with branches of the inferolateral trunk.

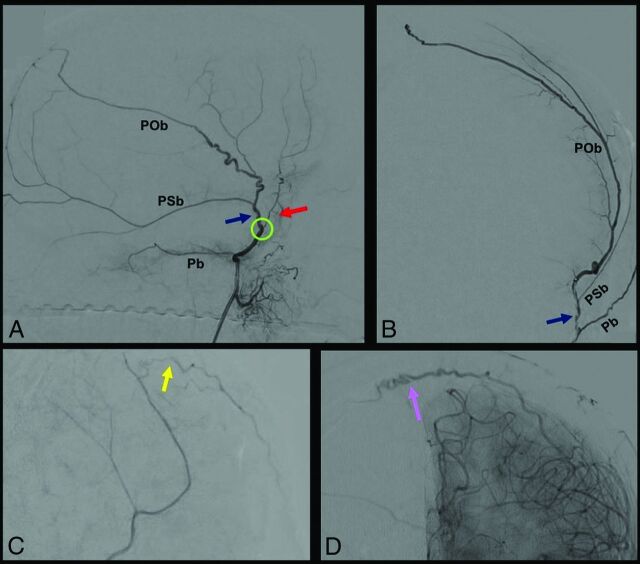

FIG 3.

DSA, showing segments and branches of the MMA. A and B, show selective MMA injection from a lateral (A) and frontal (B) view. The MMA bifurcates at the pterional region (green circle) into 2: an anterior (red arrow) and posterior (blue arrow) division. Before its bifurcation, the MMA gives the petrosal branch (Pb), which courses on the petrous apex. The posterior division gives 2 principal branches: the petrosquamosal branch (PSb) and the parieto-occipital branch (POb). The anterior division ends with 2 kinds of terminal branches, visible after common carotid artery injection: the falcine arteries (yellow arrow) (C), which anastomose with branches of the anterior falcine artery from the OA, and contralateral branches (purple arrow) (D) that cross the midline to anastomose with a contralateral MMA.

The anterior division of the MMA is in the dura of the convexity and follows the coronal suture until the bregma. This anterior division of the MMA has 2 types of terminal branches: 1) falcine arteries, which anastomose with branches of the anterior falcine artery, and 2) contralateral branches, which cross the midline to anastomose with branches of the contralateral MMA. Near the pterional region, the anterior division gives a medial branch that runs under the lesser sphenoid wing that supplies the dura of anterior part of the temporal fossa, the superior orbital fissure, and could anastomose with the recurrent meningeal branches of the OA.1,2 The posterior division of the MMA also supplies the dura of the convexity and gives 2 principal branches: the petrosquamosal branch and the parieto-occipital branch.1 These 2 branches participate in the vascularization of the parieto-temporo-occipital dura, the transverse sinuses, and also the posterior two-thirds of the tentorium.43 Branches of the posterior division of the MMA anastomose with dural branches of the occipital, ascending pharyngeal, subarcuate, and vertebral arteries.41,43

Dural Territory

The MMA supplies most of the dura of the cranial convexity via its anterior and posterior divisions, and usually participates in the vascularization of the superficial half of the falx cerebri. The frontomedial dura and the occipitomedial dura, on the contrary, are usually supplied by the anterior meningeal artery from the OA and by the posterior meningeal artery from the vertebral artery, respectively.1 The supra-tentorial dural territory of the convexity is in balance among these 3 arteries; therefore, the territory of the MMA could be variable.1,2,41 The dura of the superior sagittal sinus is also supplied by branches of the MMA but also branches of the anterior meningeal artery (anterior part) and branches of the posterior meningeal artery (posterior part).7 The MMA could also supply the torcular region via its posterior division.1

At the skull base, it supplies the middle cranial fossa and the lateral part of the anterior cranial fossa41 and also the inferior part of the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus via its cavernous branch. Its participation in the vascularization of the tentorium is limited to the insertion of the tentorium and to the superior sagittal sinus.44 The anterior division of the MMA through its medial branch supplies the dura of the lesser sphenoid wing and the superior orbital fissure region.2 These branches also participate in the vascularization of the lateral wall of the periorbita and could also participate in the vascularization of orbital branches by anastomoses with the lacrimal artery (through the deep recurrent meningeal artery of the OA).19

Through its posterior division, the MMA also gives branches destined to the dura of the superolateral part of the cerebellar fossa. Moret et al43 showed the importance of the MMA in the vascularization of the posterior fossa dura, always in balance with branches of the ascending pharyngeal and occipital arteries. The MMA also partially supplies the trigeminal and facial nerves.1-3 Indeed, the petrosal branch gives branches to the gasserian ganglion and to the maxillary and mandibular divisions of the trigeminal nerve in their cavernous portion. The greater superficial petrosal nerve and the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve also receive branches from the petrosal branch of the MMA.1 Also, the superior tympanic artery, which is the petrosal remnant of the SA and, therefore, a branch of the petrosal branch, supplies the superior part of the tympanic cavity.42

Possible Anastomoses

The dural vascular territory of the MMA is in balance between numerous arteries coming from ICA, external carotid artery, and also from the vertebrobasilar system. Therefore, the MMA presents a lot of anastomoses with branches arising from the other arteries. The 3 major anatomic regions of vascular anastomoses are the following: the peri- and the cavernous region, the frontomedial region, and the posterior fossa (Fig 4).1

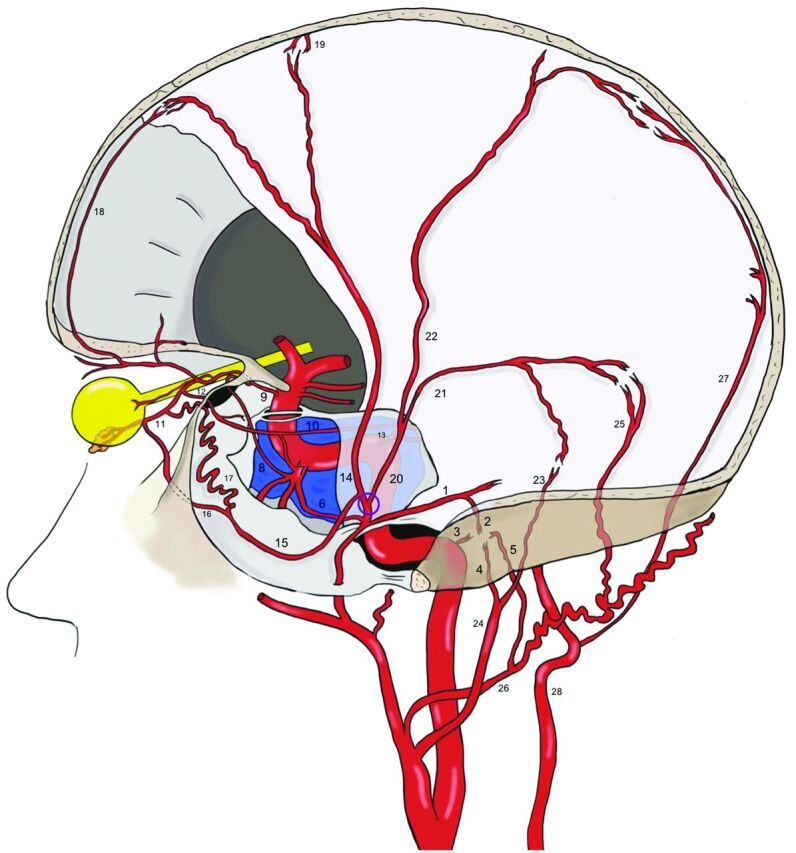

FIG 4.

Anastomoses of the MMA. Before the MMA bifurcation (purple circle), the petrous branch (1), from which the superior tympanic artery (2) originates, anastomoses into the middle ear with the caroticotympanic artery (3, from the ICA), and with the inferior tympanic artery (4, from the ascending pharyngeal artery), with the posterior tympanic artery (5, from the occipital artery). The cavernous branch of the MMA (6) on the other side anastomoses with the inferolateral trunk (ILT) (7), which is itself connected to the OA (9) through the deep recurrent OA (8). The ILT, the MMA, and the OA are also linked to each other through the marginal tentorial artery (10), whose origin can vary from the lacrimal artery (11), via superficial recurrent OA (12), to the meningohypophyseal trunk (13). After the MMA bifurcation at the pterion, its frontal division (14) gives a medial branch (15), which can bifurcate intracranially into a lateral meningolacrimal artery (16), and a medial sphenoidal artery (17). Both branches reach the lacrimal artery, even if the meningolacrimal artery more distal than the sphenoidal artery. The anastomoses with the OA and the ILT represent the most dangerous connections in the case of MMA transarterial embolization because of the risk of particle embolism into these arteries. The frontal division of the MMA reaches the convexity, following the coronal suture and anastomoses with the anterior falcine artery (18, OA–anterior ethmoidal artery) and with branches of the contralateral MMA (19). The posterior division of the MMA (20) divides into a petrosquamosal branch (21) and a parieto-occipital branch (22). The former anastomoses with the jugular branch (23) of the ascending pharyngeal artery (24) and with the mastoid branch (25) of the occipital artery (26). The latter is linked to the posterior meningeal artery (27), from the vertebral artery (28) at the border areas.

On the skull base,45 its petrosal branch anastomoses with the accessory meningeal artery, the ascending pharyngeal artery (via its carotid branch), the inferolateral trunk, the meningohypophyseal trunk, and the recurrent meningeal artery of the OA.19,41 At the frontal region, the anterior division of the MMA anastomoses principally with the dural branches of the OA: the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries and also the anterior falcine artery.15,41 In the posterior fossa, it anastomoses, principally with the posterior meningeal artery and with the mastoid branch of the occipital artery.43 The last natural anastomosis to be noted is between the MMAs of both sides on the midline.1

Clinical Implications

The understanding of the vascular anatomy of the dura mater has a major importance both for neuroradiologists and neurosurgeons because this artery is involved in many diseases.

Chronic Subdural Hematomas.

During the past 5 years, the MMA has been of interest to neuroradiologists and neurosurgeons in the treatment of recurrent chronic subdural hematomas. Mostly in patients > 65 years old, under anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy, and with mild head trauma bridging vein injury can cause chronic subdural hematoma.46 Traditional treatment consists of burr-hole evacuations, with a high rate of recurrence (2–37%).46,47 This trend is attributed to the inflammatory response caused by residual blood, which causes the formation of membranes around the hematoma. Membranes are also stimulated by angiogenic factors to neoangiogenesis, which results in the formation of fragile microcapillaries, with a high recurrent bleeding risk. In this context, some investigators, for example, Link et al,46 proposed the management of recurrent chronic subdural hematoma through endovascular MMA embolization. The MMA represents the principal blood supply of the bleeding membranes; thus, its occlusion allows the collection to be resorbed.46-48 These investigators described a recurrence rate similar to surgical evacuation but with a less-invasive procedure.46-48 Thus, this technique could represent an alternative treatment option, especially for elderly patients with recurrent chronic subdural hematoma.

Meningeal Tumors.

Meningiomas are the most common benign intracranial tumors, mostly located at the skull vault or at the skull base. Because MMA is the major dural artery, most cranial meningiomas receive its supply. Surgery represents the first-line treatment for symptomatic meningiomas, but preoperative MMA embolization could be used to reduce the blood supply of the meningioma to limit the blood loss during resection. Meningiomas, depending on their locations, can be supplied by ICA dural branches, external carotid artery dural branches, or a combination of these. Richter and Schachenmayr49 classified meningiomas into 4 types, depending on their vascular supply: type I, with exclusive external carotid artery vascularization; type II, with a mixed ICA–external carotid artery blood supply with external carotid artery prevalence; type III, with a mixed supply with an ICA prevalence; and type IV, with an exclusive ICA supply. Usually, anterior cranial fossa meningiomas are supplied by the MMA and anterior falcine artery from the OA; middle cranial fossa meningiomas are fed by MMA and dural branches of petrous and cavernous ICA.

However, posterior fossa meningiomas are rarely supplied by the MMA but from the posterior meningeal artery from the vertebral artery and from other external carotid artery branches. For these reasons, MMA embolization should be reserved for meningiomas type I or II of the Richter classification, with typical DSA blush, for middle cranial fossa and selective cases of anterior cranial fossa lesions.50 During the procedure, the neuroradiologist should keep in mind the possible anastomoses between MMA and ICA branches to avoid complications. After MMA embolization, surgery can be performed with very variable timing (from 0 to 30 days after the procedure).51 Also, the neurosurgeon has to keep in mind the general organization of the dural vascularization, which gives important help for meningioma surgery and other meningeal tumors.15

Dural AVF.

The principal dural pathology treated by neuroradiologists is the dural AVF. Also, for these procedures, a good knowledge of the precise anatomy of the MMA, of its variations, and its vascular anastomoses, helps in the avoidance of complications.3 Transarterial embolization through MMA has been described as a successful option for dural AVF treatment.52-54 According to Griessenauer et al,52 a robust MMA supply is the best predictor for successful embolization. Other factors that make the MMA a favorable way to perform transarterial embolization are its long straight course, which facilitates the penetration of Onyx, (Covidien) its quite large diameter, which allows the introduction of catheters, and its large dural territory, which often reaches dural AVFs in various locations. As already noted, the presence of an SA also has an important impact on the technical difficulty for performing a stapedectomy.49,55 The middle ear surgeon could avoid excessive blood loss by knowing the presence of such a vascular variation during the surgical planning.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- IMA

internal maxillary artery

- MMA

middle meningeal artery

- OA

ophthalmic artery

- SA

stapedial artery

References

- 1.Martins C, Yasuda A, Campero A, et al. . Microsurgical anatomy of the dural arteries. Neurosurgery 2005;56:211–51; discussion 211–51 10.1227/01.neu.0000144823.94402.3d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merland JJ, Theron J, Lasjaunias P, et al. . Meningeal blood supply of the convexity. J Neuroradiol 1977;4:129–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lasjaunias P, Bereinstein A, ter Brugge K. Surgical Neuroangiography KG. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Low FN. An anomalous middle meningeal artery. Anat Rec 1946;95:347–51 10.1002/ar.1090950310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altmann F. Anomalies of the internal carotid artery and its branches; their embryological and comparative anatomical significance; report of a new case of persistent stapedial artery in man. Laryngoscope 1947;57:313–39 10.1288/00005537-194705000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seeger JF, Hemmer JF. Persistent basilar/middle meningeal artery anastomosis. Radiology 1976;118:367–70 10.1148/118.2.367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasjaunias P, Moret J, Manelfe C, et al. . Arterial anomalies at the base of the skull. Neuroradiology 1977;13:267–72 10.1007/BF00347072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz M, Wisoff HS, Zimmerman RD. Basilar-middle meningeal artery anastomoses associated with a cerebral aneurysm. Case report. J Neurosurg 1981;54:677–80 10.3171/jns.1981.54.5.0677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah QA, Hurst RW. Anomalous origin of the middle meningeal artery from the basilar artery: a case report. J Neuroimaging 2007;17:261–63 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2007.00108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuruvilla A, Aguwa AN, Lee AW, et al. . Anomalous origin of the middle meningeal artery from the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. J Neuroimaging 2011;21:269–72 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2010.00475.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S, Mishra NK. Middle meningeal artery arising from the basilar artery: report of a case and its probable embryological mechanism. J Neurointerv Surg 2012;4:43–44 10.1136/jnis.2010.004465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salem MM, Fusco MR, Dolati P, et al. . Middle meningeal artery arising from the basilar artery. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg 2014;16:364–67 10.7461/jcen.2014.16.4.364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waga S, Okada M, Yamamoto Y. Basilar-middle meningeal arterial anastomosis. Case report. J Neurosurg 1978;49:450–52 10.3171/jns.1978.49.3.0450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steffen TN. Vascular anomalites of the middle ear. Laryngoscope 1968;78:171–97 10.1288/00005537-196802000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dilenge D, Ascherl GF Jr.. Variations of the ophthalmic and middle meningeal arteries: relation to the embryonic stapedial artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1980;1:45–54 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabriele OF, Bell D. Ophthalmic origin of the middle meningeal artery. Radiology 1967;89:841–44 10.1148/89.5.841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brucher J. Origin of the ophthalmic artery from the middle meningeal artery. Radiology 1969;93:51–52 10.1148/93.1.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Royle G, Motson R. An anomalous origin of the middle meningeal artery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1973;36:874–76 10.1136/jnnp.36.5.874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moret J, Lasjaunias P, Théron J, et al. . The middle meningeal artery. Its contribution to the vascularisation of the orbit. J Neuroradiol 1977;4:225–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diamond MK. Homologies of the meningeal-orbital arteries of humans: a reappraisal. J Anat 1991;178:223–41 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Q, Rhoton AL Jr.. Middle meningeal origin of the ophthalmic artery. Neurosurgery 2001;49:401–06; discussion 406-07 10.1097/00006123-200108000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plas B, Bonneville F, Dupuy M, et al. . Bilateral ophthalmic origin of the middle meningeal artery. Neurochirurgie 2013;59:183–86 10.1016/j.neuchi.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cvetko E, Bosnjak R. Unilateral absence of foramen spinosum with bilateral ophthalmic origin of the middle meningeal artery: case report and review of the literature. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2014;73:87–91 10.5603/FM.2014.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimball D, Kimball H, Tubbs RS, et al. . Variant middle meningeal artery origin from the ophthalmic artery: a case report. Surg Radiol Anat 2015;37:105–08 10.1007/s00276-014-1272-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curnow J. Two instances of irregular ophthalmic and middle meningeal arteries. J Anat Physiol 1873;8(pt 1):155–56 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer F. About the anatomy of orbital arteries. Morph Jahr 1887;12:414–58 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuckerkandl E. Zur Anatomie der Orbita Arterien. Med Jahr 1876:343 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lasjaunias P, Moret J. Normal and non-pathological variations in the angiographic aspects of the arteries of the middle ear. Neuroradiology 1978;15:213–19 10.1007/BF00327529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maiuri F, Donzelli R, de Divitiis O, et al. . Anomalous meningeal branches of the ophthalmic artery feeding meningiomas of the brain convexity. Surg Radiol Anat 1998;20:279–84 10.1007/BF01628491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodesch G, Choi IS, Lasjaunias P. Complete persistence of the hyoido-stapedial artery in man. Case report. Intra-petrous origin of the maxillary artery from ICA. Surg Radiol Anat 1991;13:63–65 10.1007/BF01623146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher AG. A case of complete absence of both internal carotid arteries, with a preliminary note on the developmental history of the stapedial artery. J Anat Physiol 1913;48(pt 1):37–46 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guinto FC Jr, Garrabrant EC, Radcliffe WB. Radiology of the persistent stapedial artery. Radiology 1972;105:365–69 10.1148/105.2.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teal JS, Rumbaugh CL, Bergeron RT, et al. . Congenital absence of the internal carotid artery associated with cerebral hemiatrophy, absence of the external carotid artery, and persistence of the stapedial artery. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1973;118:534–45 10.2214/ajr.118.3.534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLennan JE, Rosenbaum AE, Haughton VM. Internal carotid origins of the middle meningeal artery. The ophthalmic-middle meningeal and stapedial-middle meningeal arteries. Neuroradiology 1974;7:265–75 10.1007/BF00344246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheikh BY, Coates R, Siqueira EB. Stapedial artery supplying sphenoid wing meningioma: case report. Neuroradiology 1993;35:537–38 10.1007/BF00588716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawai K, Yoshinaga K, Koizumi M, et al. . A middle meningeal artery which arises from the internal carotid artery in which the first branchial artery participates. Ann Anat 2006;188:33–38 10.1016/j.aanat.2005.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koenigsberg RA, Zito JL, Patel M, et al. . Fenestration of the internal carotid artery: a rare mass of the hypotympanum associated with persistence of the stapedial artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995;16(suppl):908–10 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silbergleit R, Quint DJ, Mehta BA, et al. . The persistent stapedial artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:572–77 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baltsavias G, Kumar R, Valavanis A. The pharyngo-tympano-stapedial variant of the middle meningeal artery. A case report. Interv Neuroradiol 2012;18:255–58 10.1177/159101991201800302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diamond MK. Unusual example of a persistent stapedial artery in a human. Anat Rec 1987;218:345–54 10.1002/ar.1092180316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salamon G, Grisoli J, Paillas JE, et al. . Arteriographic study of the meningeal arteries. (role of selective injections, of subtraction and of radio-anatomical correlations). Neurochirurgia (Stuttg) 1967;10:1–19 10.1055/s-0028-1095333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salamon G, Guérinel G, Demard F. Radioanatomical study of the external carotid artery. Ann Radiol (Paris) 1968;11:199–215 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moret J, Lasjaunias P, Vignaud J, et al. . The middle meningeal blood supply to the posterior fossa (author's transl). Neuroradiology 1978;16:306–07 10.1007/BF00395283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silvela J, Zamarron MA. Tentorial arteries arising from the external carotid artery. Neuroradiology 1978;14:267–69 10.1007/BF00418627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Margolis MT, Newton TH. Collateral pathways between the cavernous portion of the internal carotid and external carotid arteries. Radiology 1969;93:834–36 10.1148/93.4.834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Link TW, Boddu S, Marcus J, et al. . Middle meningeal artery embolization as treatment for chronic subdural hematoma: a case series. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2018;14:556–62 10.1093/ons/opx154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fiorella D, Arthur AS. Middle meningeal artery embolization for the management of chronic subdural hematoma. J Neurointerv Surg 2019;11:912–15 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-014730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haldrup M, Ketharanathan B, Debrabant B, et al. . Embolization of the middle meningeal artery in patients with chronic subdural hematoma-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020;162:777–84 10.1007/s00701-020-04266-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richter HP, Schachenmayr W. Preoperative embolization of intracranial meningiomas. Neurosurgery 1983;13:261–68 10.1227/00006123-198309000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dubel GJ, Ahn SH, Soares GM. Contemporary endovascular embolotherapy for meningioma. Semin Intervent Radiol 2013;30:263–77 10.1055/s-0033-1353479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah A, Choudhri O, Jung H, et al. . Preoperative endovascular embolization of meningiomas: update on therapeutic options. Neurosurg Focus 2015;38:E7 10.3171/2014.12.FOCUS14728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Griessenauer CJ, He L, Salem M, et al. . Middle meningeal artery: gateway for effective transarterial Onyx embolization of dural arteriovenous fistulas. Clin Anat 2016;29:718–28 10.1002/ca.22733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayashi K, Ohmoro Y, KY, et al. . Non-sinus-type dural arteriovenous fistula cured by transarterial embolization from middle meningeal artery: two case reports. J Neuro Endovasc Ther 2018;12:542–45 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hlavica M, Ineichen BV, Fathi AR, et al. . Parasagittal dural arteriovenous fistula treated with embozene microspheres. J Endovasc Ther 2015;22:952–55 10.1177/1526602815604464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maran AG. Persistent stapedial artery. J Laryngol Otol 1965;79:971–75 10.1017/s0022215100064665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]