Abstract

This study examined the development and continuity of teacher-student relationship quality across the formal schooling years (grades 1 to 12) and investigated how variations (i.e., differential trajectories) in teacher-student relationship quality were longitudinally associated with children’s conduct problems across childhood and adolescence. Participants consisted of 784 students (Mage = 6.57 in grade 1; 47% girls, 37.4% Latino or Hispanic, 34.1% European American, and 23.2% African American) who were identified as being academically at risk (i.e., had low literacy scores at school entry). Distinct subgroups of children were identified based on variations in their teacher-student warmth and conflict trajectories, and patterns of continuity and change were also assessed across the transition to middle school. The findings provided insights into how the duration, magnitude, and timing of teacher-student relationship quality were associated with children’s conduct problems. More specifically, relationships characterized by early-onset deficits, chronic and persistent relationship difficulties, or adolescent-onset conflict were associated with distinct patterns of conduct problems throughout childhood and adolescence.

Keywords: teacher-student relationships, teacher-child relationships, conduct problems, externalizing problems, school transitions

The quality of children’s interpersonal relationships with teachers has a significant impact on their social-emotional and academic outcomes (Davis, 2003; Nurmi, 2012; Pianta, 1999; Roorda, Koomen, Spilt, & Oort, 2011). Moreover, high quality teacher-student relationships (TSR) are particularly impactful for students at risk for academic problems (Baker, Grant, & Morlock, 2008; Bosman, Roorda, van der Veen, & Koomen, 2018; McGrath & van Bergen, 2015; Murray & Zvoch, 2011). For these students, a warm and supportive relationship may serve as an important protective factor which may alleviate or reduce some of their risks for scholastic and academic difficulties and their behavioral (i.e., conduct) problems. Consequently, it is imperative for researchers, educators, and practitioners to better understand the quality and development of TSR. Building on this area of research, the aims of the present study were twofold: (a) to examine the developmental trajectories and continuity of teacher-student relationships (TSR) across the formal schooling years (grades 1 to 12), and (b) to examine how individual differences in teacher-student relationship qualities are longitudinally associated with children’s conduct problems. For both aims, developmental differences were assessed by comparing the findings during the primary (grades 1 to 5) and secondary (grades 6 to 12) school years. Moreover, these aims were investigated in a sample of children who were identified to be academically at risk at school entry.

Theoretical Perspectives on Teacher-Student Relationships

Reformulations of attachment theory have been proposed to explain the nature of teacher-student relationship quality and its impact on children’s social development and adjustment within school contexts (Pianta, 1999; Sabol & Pianta, 2012). According to this perspective, close and supportive TSR, which are characterized by open communication, trust, and responsiveness, provide children with the emotional security to more effectively cope with academic and social stressors and to feel a sense of belonging in the classroom context (Bosman et al., 2018; Hughes & Cao, 2018). Applying this perspective, researchers have primarily assessed two dimensions of TSR, consisting of teacher-student warmth (also referred to as closeness) and conflict. Teacher-student warmth is characterized by relationships which are supportive, mutually responsive, and high in positive affect and emotional closeness. In contrast, teacher-student conflict reflects relationships that are discordant, unresponsive, and high in negative affect and hostility (O’Connor, Collins, & Supplee, 2012). Although these dimensions are interrelated, they reflect distinct facets of TSR, such that a high-quality relationship consists of high warmth and low conflict. Consistent with this conceptualization of multiple dimensions of TSR, in the current study we differentiated the development of warmth and conflict. Notably, some investigators have also considered dependency as a third dimension of TSR. However, this construct appears to be more developmentally salient for younger children in comparison to older children and adolescents (Baker et al., 2008), thus it was not assessed in the present study.

One of the primary assumptions of attachment theory is that, over time, children’s interpersonal interactions and relationships influence the formation of internal working models, or generalized cognitive representations (e.g., schemas) pertaining to their interpretations and expectations in significant relationships (Bowlby, 1988; Davis, 2003; Howes, Hamilton, & Philipsen, 1998). Although students must form relationships with new and unfamiliar teachers as they transition between grades and schools, one of the implications of this perspective is that prior experiences with teachers may continue to have a profound influence on the quality of subsequent TSR. Moreover, investigators have posited that as children’s expectations are reinforced by their relational experiences over time, their internal working models become more stable and less flexible to change (Howes, Phillipsen, & Peisner-Feinberg, 2000). Thus, the quality of TSR may exhibit greater stability and continuity as children mature.

Development and Continuity of Teacher-Student Relationships

Existing studies, conducted with both low-risk and at-risk populations, have reported moderate stability rates in TSR over time (Jerome, Hamre, & Pianta, 2009; O’Connor, 2010), with findings indicating that teacher-student conflict has relatively higher rates of stability than warmth (Howes et al., 2000; Jerome et al., 2009; Silver, Measelle, Armstrong, & Essex, 2005; Spilt, Hughes, Wu, & Kwok, 2012). In addition to variable-centered studies that have reported on rank-order stability, investigators have also used latent growth curve modeling to examine intra-individual trajectories over time. These studies have typically taken two approaches. The first approach has been to examine normative developmental trends over time, and the second has been to examine heterogeneity (i.e., individual differences) in the developmental trajectories of TSR.

With respect to normative (i.e., average or mean-level) trends, Jerome and colleagues (2009) found that teacher-student conflict and closeness exhibited distinct non-linear trends from Kindergarten to Grade 6. More specifically, conflict increased from kindergarten to Grade 4 and then decreased from Grade 4 to Grade 6 (i.e., an inverse u-shaped trajectory). In contrast, closeness decreased from Kindergarten to Grade 6, with the rate of decline becoming more pronounced in later grades (for similar results, see Crockett, Wasserman, Rudasill, Hoffman, & Kalutskaya, 2018; Lee & Bierman, 2018). Examining a relatively longer developmental period and utilizing a sample of children at risk for academic problems, Wu and Hughes (2015) also reported a declining trend for teacher-student warmth from Grades 1 to 9, with rates of decline being more pronounced during the transition to middle school. However, teacher-student conflict exhibited a modest linear decline over this same time period. Taken together, results from these investigations indicated significant mean-level changes in the quality of TSR throughout the primary school years and as children transition to middle school.

In addition to examining normative trends, several researchers have used person-centered methods to identify distinct subgroups of children who exhibit heterogeneous developmental trajectories of warmth and conflict. Notably, these studies have relied primarily on teachers’ perceptions (reports) of TSR and have been conducted with both typical (low-risk) and at-risk samples. With respect to teacher-student warmth (and closeness), results from three studies (see Bosman et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2012; Spilt et al., 2012) collectively indicated between two to four distinct trajectory classes, spanning from Pre-kindergarten to Grade 6 (for additional examples of studies which examined relationship quality more broadly, see Miller-Lewis et al., 2014; O’Connor & McCartney, 2007). More specifically, all three of these studies identified a high-decreasing trajectory and a low/moderate increasing trajectory. Two studies identified a high stable trajectory and one study reported a low-stable trajectory. Although the majority of children were either in the high-stable or high-declining trajectories, a smaller proportion of children exhibited lower levels of warmth over time.

These three studies also examined trajectories of teacher-student conflict during early and middle childhood and identified three to six distinct trajectory classes. Results indicated that the majority of children (from 57% to 88%) had low-stable levels of conflict. Moreover, all three studies identified a subset of children exhibiting either increasing or decreasing trajectories over time (e.g., low- or moderate-increasing, high- or moderate-decreasing). Finally, two of these studies reported that some children had chronically high levels of conflict over time.

In contrast to studies which investigated normative trends, findings from person-centered studies have implied that there is considerable heterogeneity in developmental trajectories of warmth and conflict during elementary school (i.e., inter-individual differences in intra-individual changes). Taken together, findings from these studies revealed that far more is known about developmental trajectories and normative trends among elementary school aged children compared to high schoolers. An important question that remains understudied pertains to how trajectories, identified during the secondary school years (i.e., Grades 6 to 12), compare with those identified in primary school. On the one hand, according to attachment perspectives, children’s internal working models become more stable over time and generalize to other relationships. Thus, it would be expected that there would be considerable continuity or stability in relationship quality over time. Stated differently, children who experience persistently high-quality relationships in primary school are likely to have similar experiences in secondary school, and children with chronically conflictual relationships in the earlier years are more likely to experience sustained conflict in adolescence (middle and high school).

On the other hand, it is plausible that TSR are influenced by the significant developmental and contextual changes that coincide with the middle school transition. From a developmental perspective, the transition to middle school occurs when early adolescents are also experiencing considerable biological (pubertal) and cognitive changes, the need to become more emotionally and behaviorally autonomous, and spending increasing amounts of time with peers. These changes typically motivate adolescents to rely less on adults, including their parents and teachers, for emotional support (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1997). In addition to these developmental processes, there are significant contextual (i.e., school- and classroom-based) challenges that most adolescents face as they transition to middle school. Some of the more salient challenges include more rigorous academic demands, an emphasis on instruction and performance, having multiple teachers, and larger classes and student-to-teacher ratios, collectively resulting in less time and fewer opportunities to interact with teachers and form supportive TSR (Maldonado-Carreño & Votruba-Drzal, 2011; O’Connor & McCartney, 2007; Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000).

Although many of these developmental and contextual changes are viewed as being normative, when applying the stage-environment fit theory researchers have proposed that there is a mismatch between students’ psychological and developmental needs and the traditional middle school structure (Eccles & Midgely, 1989; Lynch & Cicchetti, 1997). For instance, although early adolescents strive for increased autonomy and independent decision-making, they are confronted with an academic environment that is more competitive, performance oriented and structured, and less flexible to student input (Davis, 2003). Consistent with this perspective, many students may view their teachers as being less available and emotionally supportive relative to their teachers in elementary school. Indeed, investigators have found that the middle school transition is associated with a significant drop in teacher-student warmth, over and above the normative rate of decline occurring prior to this transition (Hughes & Cao, 2018). Moreover, this decline has been substantiated in studies that have relied on teacher-reports (Hughes & Cao, 2018) and students’ perceptions (Niehaus, Rudasill, & Rakes, 2012). Considering that these developmental and contextual processes may contribute to a sensitive period in which adolescents reevaluate and redefine their expectations pertaining to their TSR, we propose that the middle school transition may mark a significant shift for some children in their developmental trajectories of teacher-student warmth and conflict. Furthermore, this is an important period to better understand the heterogeneity in teacher-student relationship trajectories as teachers may function as crucial assets in supporting adolescents, particularly those adolescents at risk for academic and behavioral problems based on the challenges they may experience during this transition (Murray & Zvoch, 2011; Roorda et al., 2011; Sabol & Pianta, 2012).

Children’s Conduct Problems and Teacher-Student Relationship Quality

There is a substantial body of evidence demonstrating that children’s conduct and externalizing problems, characterized by aggressive and disruptive behaviors, are strongly associated with lower quality TSR (Hamre, Pianta, Downer, & Mashburn, 2007; Henricsson & Rydell, 2004; McGrath & Van Bergen, 2015; Mejia & Hoglund, 2016; Nurmi, 2012). Children who engage in these behaviors are more likely to display antagonistic and hostile interaction styles with classmates and teachers and disrupt classroom learning activities, resulting in more frequent disciplinary and academic problems (Miles & Stipek, 2006).

The empirical evidence pertaining to the longitudinal associations between TSR and conduct problems has been garnered from multiple studies which have utilized both variable-centered and person-centered approaches. Taken together, several general conclusions can be drawn from variable-centered studies on TSR and conduct problems. Although these studies corroborate the premise that there are strong concurrent and prospective associations between TSR and conduct problems (Doumen et al., 2008; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Ly & Zhou, 2018; Mejia & Hoglund, 2016; Pakarinen et al., 2018; Skalická, Stenseng, & Wichstrøm, 2015; Zhang & Sun, 2011), there are stronger and more consistent associations between conduct problems and conflict than warmth (Ly & Zhou, 2018; Mejia & Hoglund, 2016) and for teacher as compared to parent-reported conduct problems (Crockett et al., 2018; Skalická et al., 2015). However, most of these studies have been based on short-term longitudinal designs to investigate discrete developmental periods or stages (e.g., within a school year or across a few grade levels) and have been conducted in early and middle childhood. Thus, far less is known about the long-term associations between TSR and conduct problems, particularly in adolescence.

Expanding on the findings from variable-centered studies, several investigators have used person-centered designs to examine how children’s conduct problems are associated with varying trajectories of teacher-student warmth and conflict across time. These studies have primarily addressed three aims: (a) to examine the predictive effects of conduct problems on children’s relationship trajectories, (b) to examine conduct problems as an outcome of children’s relationship trajectories, and (c) to examine dynamic or co-occurring development of TSR and conduct problems across time. With respect to the first aim, Bosman and colleagues (2018) found that externalizing behaviors in Kindergarten were positively associated with elevated levels of conflict from Kindergarten to Grade 6 (i.e., increased membership in high-decreasing and low-increasing trajectory groups compared to the low-stable group). Similarly, examining a sample of children at-risk for academic problems, Spilt and colleagues (2012) and Spilt and Hughes (2015) found that higher conduct problems in Grade 1 increased the likelihood of children having high-stable, high-declining, and low-increasing conflict trajectories from Grades 1 to 5 in comparison to low-stable conflict. These investigators also reported that early conduct problems were associated with less adaptive and positive teacher-student warmth trajectories throughout elementary school. With respect to the second aim, O’Connor and colleagues (2012) found that compared to children with low-stable conflict trajectories from Pre-kindergarten to Grade 5, those in any of the five more maladaptive conflict trajectory groups exhibited higher levels of externalizing problems in Grade 5. However, Grade 5 externalizing problems were not associated with children’s closeness trajectories. With respect to the third aim, O’Connor and colleagues (2011) examined how differential trajectories of TSR in elementary school were associated with children’s externalizing trajectories during the same time period. They found that compared to children with more positive relationship trajectories, those with more problematic relationship trajectories were more likely to exhibit higher levels of co-occurring externalizing problems. However, these investigators used a composite measure of TSR which did not differentiate the conflict and warmth dimensions.

Study Aims and Hypotheses

Building on these findings, the primary purpose of the current study was to apply a person-centered approach to investigate the long-term, dynamic, and co-occurring associations between TSR and conduct problems across the entirety of primary and secondary schooling (Grades 1 to 12). More specifically, the first aim of this study was to identify subgroups of children who exhibited heterogeneous developmental patterns (i.e., continuity and changes) in their teacher-student conflict and warmth across the formal schooling years. Moreover, to assess potential developmental differences before and after the middle school transition, developmental trajectories were examined separately from Grades 1 to 5 and 6 to 12.

Based on these previously described studies that have examined warmth and conflict trajectories during elementary school, we hypothesized identifying at least four distinct classes for each form of relationship quality in elementary school: two classes characterized by continuity (i.e., low-stable and high-stable classes), and two classes characterized by change or discontinuity (i.e., low- or moderate-increasing and high- or moderate-decreasing). Although we hypothesized that the number and types of trajectory classes were similar for warmth and conflict, we expected different class proportions for these two forms of TSR. That is, the majority of children were expected to be in the high warmth and low conflict trajectories, and smaller subgroups were expected in the remaining classes. In light of findings which indicate normative declines in warmth as children get older, particularly in middle school, we expected that the high warmth class would exhibit a decline after the transition to middle school. Exactly how the nature of children’s increasing or decreasing trajectories would change or stabilize after the transition to middle school remained a more exploratory question. It is plausible that the transition to middle school may introduce additional stressors that would further exacerbate the quality of TSR, thus leading to greater declines in warmth and increases in conflict. Conversely, with fewer opportunities to interact and build relationships with teachers in middle school, it is plausible that there would be less variability in TSR, and thus trajectories may converge (i.e., become more similar) as children progressed through secondary school. To assess the individual characteristics of children in each trajectory class, we also examined the associations among the differential trajectory classes and children’s gender, ethnicity, race, socioeconomic status, early conduct problems, early academic performance, and grade retention.

The second aim of this study was to assess continuity and changes in conduct problems across Grades 1 to 12 based on differences in children’s relationship trajectories (i.e., those identified in the first aim). Although it is well established that conduct problems and TSR are associated, less is known about the duration, magnitude and timing of these associations across childhood and adolescence. Accordingly, in light of current theory and evidence, we proposed several alternative hypotheses pertaining to how variations in the duration, timing, and magnitude of TSR may coincide with distinct patterns of continuity and changes in children’s conduct problems across childhood and adolescence.

First, given the well-established associations between early conduct problems and TSR (e.g., in preschool, kindergarten, and early elementary school), we expected that children with initially high conflict or low warmth trajectories would exhibit early-onset conduct problems. Second, researchers have differentiated early- and adolescent-onset conduct problems and have theorized that adolescent-onset conduct problems are more strongly impacted by environmental and interpersonal stressors (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001). Although adolescent-onset conduct problems typically have been studied in relation to the peer and parent-child context (Ettekal & Ladd, 2015; Moffitt & Caspi, 2001), it is possible that teachers are an additional source of stress (conflict) or support (warmth) which promote (or deter) the development of adolescent-onset conduct problems. Thus, we evaluated the hypothesis that increasing conflict and decreasing warmth may be associated with increases in conduct problems in adolescence.

Third, in light of chronic stress perspectives which suggest that longer and more severe exposure to a risk factor increases resultant maladjustment (Ladd, Ettekal, & Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2017; Lin & Ensel, 1989), we expected that children with persistently higher levels of conflict would exhibit sustained conduct problems in childhood and adolescence. Fourth, as a corollary to chronic stress perspectives, investigators (e.g., Ladd et al., 2017) also have proposed a recovery hypothesis. According to a recovery hypothesis, as relational stressors diminish over time, there are co-occurring improvements (recovery) in children’s adjustment. Thus, it may be the case that children with declining conflict also would exhibit reductions in conduct problems. Although the chronic stress and recovery perspectives have been typically applied to conditions of stress exposure that align more closely with teacher-student conflict, we also considered the implications of these perspectives for teacher-student warmth. That is, children who persistently lack warm and supportive relationships with teachers may be at greater risk for sustained conduct problems. Alternatively, increases in teacher-student warmth across time may provide children with the relational supports to improve their behavioral adjustment and exhibit declines in conduct problems.

Method

Participants

Participants were 784 children who were part of a multi-ethnic, predominantly low SES sample recruited when they were in the first grade from three different school districts (one urban and two small cities) in Texas as part of a larger longitudinal study called ‘Project Achieve’. Because the broader aims of this project were to examine educational outcomes in an academically at-risk sample, children were eligible to participate in this study if they scored below the median in their school district on a district-administered test of literacy (administered in the spring of kindergarten or the fall of Grade 1). Additional eligibility criteria included not receiving special education services, speaking English or Spanish as a first language, and not having been previously retained in first grade. A total of 1374 first graders were recruited to participate and were provided with parental consent forms, of which 1200 consent forms were returned with 784 parents agreeing to have their children participate in the study. Chi-square tests indicated that there were no significant differences between the eligible participants with and without parental consent on literacy test scores, age, gender, ethnicity, family income, or bilingual class placement (for additional details on sampling procedures, see Hill & Hughes, 2007; Hughes & Kwok, 2007).

The average age of participants was 6.57 years when they were in Grade 1. About 47.0% of children were girls, 37.4% were Latino/Hispanic, 34.1% were European American, 23.2% were African American, and about 5.4% were Asian, Native American, or Pacific Islander. About 65.0% of participants were low SES as indicated by income-based eligibility for free or reduced lunch, and 42.5% had parents with a high school diploma or less educational attainment. Due to the sampling design and eligibility criteria to select children who were at risk for academic problems, children were recruited from a large number of classrooms and schools, and also became increasingly dispersed over time. Data from this project are publically available for secondary data analysis at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Data and Specimen Hub (DASH; https://dash.nichd.nih.gov/study/14412).

Procedure

As part of the longitudinal research design, data collection was performed on an annual basis over 12 years (from Grade 1 to Grade 12; however, no assessments were collected in Grade 11). For the purposes of the present study, multi-informant data from school districts, individually administered standardized tests, teacher-reports, and parent-reports were used. Participating school districts provided the research staff with information on participants’ demographic background (i.e., age, gender, race, ethnicity, and eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch) and classes (e.g., bilingual class placement). Trained research staff administered standardized tests to assess children’s academic (math and reading) performance (in Grade 1).

Parents completed questionnaires annually (with the exception of Grade 11) on their child’s behavioral adjustment (conduct problems). If children were enrolled in a bilingual education program or spoke any Spanish (as reported by their teachers), the children’s parents were mailed both English and Spanish versions of the questionnaires. Spanish assessments were translated and back translated using standard translation procedures. Overall, there was a small percentage of parents who completed Spanish versions of the questionnaires, and this percentage declined over time (i.e., from 8.5% in Grade 1 to 1.5% in Grade 12).

Annually (i.e., in the spring of each year from Grades 1 to 12, with the exception of Grade 11), teachers completed questionnaires assessing students’ behavioral adjustment (i.e., conduct problems) and the teachers’ relationship quality with participating students. In the elementary grades, the students’ primary classroom teacher completed the questionnaire. After the transition to middle school, questionnaires were completed by the student’s language arts teacher (93%) or a teacher named by the language arts teacher as having greater knowledge of the student (7%). The choice of relying on language arts teachers was based primarily on the rationale that all students were required to take language arts courses annually and would be evaluated in a similar instructional context as other participants. Across Grades 1 to 12, on average, there were 231 teachers (range: 147–358) from 69 schools (range: 34–118) participating in data collection each year. Most teachers were female (range: 70.1%−98.3%) and White (range: 76.7%−91.0%), with smaller percentages of Hispanic/Latino (range: 1.1%−16.1%) and African American teachers (range: 2.1%–16.8%). Across each year’s data collection, teachers who had Bachelor’s degrees ranged from 33.2% to 67.8% and those with Master’s degrees ranged from 12.8% to 43.5%. Teachers with less than three years of teaching experience ranged from 13.1% to 28.8%, teachers with 4–6 years of experience ranged from 10.4% to 28.9%, teachers with 7–12 years of experience ranged from 14.6% to 30.9%, and teachers with more than 12 years of experience ranged from 25.9% to 47.2%. Teachers reported spending a range of 1.1 to 6.3 hours with their students on a daily basis across years of data collection, consistent with the varying classroom structures of primary and secondary schools.

Measures

Teacher-student relationship quality

Each year, teachers completed the 22-item Teacher Network of Relationships Inventory (TRNI; Hughes & Kwok, 2006). For the current study, the Warmth (13 items; e.g., ‘I enjoy being with this child’; ‘This child gives me many opportunities to praise him or her’) and Conflict (6 items; e.g., ‘This child and I often argue or get upset with each other’; ‘I often need to discipline this child’) subscales were used. Teachers rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = “not at all true” to 5 = “very true”) with higher scores indicating higher levels of warmth and conflict. Previous studies with this sample have demonstrated that these subscales exhibit construct, factorial, and predictive validity, longitudinal invariance, and measurement invariance across gender and ethnicity (Hughes, 2011; Wu & Hughes, 2015). Both subscales exhibited adequate reliability over time (alphas ranged from .94 to .96 for warmth and .91 to .94 for conflict). Descriptive statistics and scale reliabilities are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Variable | Wave | N | Min | Max | M | SD | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 784 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.50 | - | |

| African American | 784 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.23 | 0.42 | - | |

| Hispanic | 784 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 0.48 | - | |

| Academic performance | 757 | −2.89 | 3.12 | 0.00 | 1.00 | - | |

| Socioeconomic adversity | 776 | −1.27 | 1.66 | 0.04 | 0.74 | - | |

| Grade retention | 784 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.47 | - | |

| Teacher-child warmth | G1 | 699 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.01 | 0.81 | 0.95 |

| G2 | 623 | 1.08 | 5.00 | 3.93 | 0.85 | 0.95 | |

| G3 | 547 | 1.15 | 5.00 | 3.94 | 0.85 | 0.96 | |

| G4 | 528 | 1.15 | 5.00 | 3.90 | 0.88 | 0.95 | |

| G5 | 541 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.85 | 0.86 | 0.94 | |

| G6 | 439 | 1.31 | 5.00 | 3.74 | 0.95 | 0.96 | |

| G7 | 430 | 1.08 | 5.00 | 3.59 | 0.96 | 0.96 | |

| G8 | 438 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.44 | 1.01 | 0.96 | |

| G9 | 406 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.53 | 0.92 | 0.95 | |

| G10 | 436 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.52 | 0.91 | 0.95 | |

| G12 | 390 | 1.08 | 5.00 | 3.49 | 0.93 | 0.95 | |

| Teacher-child conflict | G1 | 702 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.88 | 1.02 | 0.92 |

| G2 | 623 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.84 | 1.00 | 0.92 | |

| G3 | 547 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.79 | 0.95 | 0.92 | |

| G4 | 528 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.74 | 0.91 | 0.91 | |

| G5 | 541 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.73 | 0.92 | 0.93 | |

| G6 | 439 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.67 | 0.93 | 0.94 | |

| G7 | 430 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.66 | 0.96 | 0.94 | |

| G8 | 438 | 1.00 | 4.67 | 1.61 | 0.87 | 0.92 | |

| G9 | 406 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.55 | 0.79 | 0.92 | |

| G10 | 436 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.56 | 0.82 | 0.93 | |

| G12 | 391 | 1.00 | 4.75 | 1.47 | 0.79 | 0.92 | |

| Conduct problems (PR) | G1 | 495 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 2.03 | 1.96 | 0.69 |

| G2 | 480 | 0.00 | 9.00 | 1.97 | 1.97 | 0.72 | |

| G3 | 477 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 1.82 | 1.97 | 0.72 | |

| G4 | 446 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.74 | 1.97 | 0.73 | |

| G5 | 432 | 0.00 | 9.00 | 1.71 | 1.84 | 0.69 | |

| G6 | 363 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.63 | 1.77 | 0.65 | |

| G7 | 335 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.61 | 1.84 | 0.71 | |

| G8 | 352 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.68 | 1.92 | 0.73 | |

| G9 | 352 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.57 | 1.92 | 0.73 | |

| G10 | 345 | 0.00 | 9.00 | 1.59 | 1.81 | 0.67 | |

| G12 | 281 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.20 | 1.61 | 0.67 | |

| Conduct problems (TR) | G1 | 675 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.83 | 2.42 | 0.84 |

| G2 | 619 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.81 | 2.47 | 0.83 | |

| G3 | 547 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.73 | 2.33 | 0.82 | |

| G4 | 528 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.71 | 2.35 | 0.82 | |

| G5 | 541 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.65 | 2.35 | 0.84 | |

| G6 | 439 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.59 | 2.31 | 0.84 | |

| G7 | 430 | 0.00 | 9.00 | 1.47 | 2.05 | 0.79 | |

| G8 | 437 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.39 | 2.07 | 0.80 | |

| G9 | 406 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 1.15 | 1.73 | 0.77 | |

| G10 | 435 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 1.24 | 1.91 | 0.77 | |

| G12 | 390 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 1.01 | 1.76 | 0.80 |

Note: Gender, African American, Hispanic, and grade retention variables were dichotomized scores. Socioeconomic adversity and academic performance were standardized scores. G = Grade; PR = parent report; TR = teacher report

Conduct problems

Each year, teachers and parents completed the 25-item Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997) using a 3-point Likert-scale (0 = “not true”, 1 = “somewhat true”, 2 = “certainly true”). The five items (e.g., often fights, lies or cheats, steals from home, school or elsewhere, loses temper) from the Conduct Problems subscale were aggregated (summed) to form a composite scale score. The SDQ has been widely used in educational and psychological research and has demonstrated adequate validity and reliability (Goodman, 1997; Goodman & Goodman, 2009; Stone et al., 2010). Within the current sample, the conduct problems scale exhibited adequate reliability over time (alphas ranged from .77 to .84 for teacher reports and from .65 to .73 for parent reports). Teacher- and parent-reports were moderately and significantly correlated within each wave (rs ranged from .33 to .46, p < .001), with the exception of grade 12 (r = .10, p = .13).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess longitudinal measurement invariance for teacher- and parent-reports of conduct problems across time. For each informant, three measurement models were specified. In the first set of models, factor loadings and intercepts were unconstrained (configural invariance for teacher reports: χ2 = 2078.88, df = 1314, RMSEA = .27, SRMR = .055, CFI = .915; for parent reports: χ2 = 1596.08, df = 1089, RMSEA = .026, SRMR = .057, CFI = .921). In the second set of models, factor loadings were constrained for similar items over time (metric invariance: for teacher reports: χ2 = 2195.62, df = 1354, RMSEA = .028, SRMR = 0.066, CFI = .907; for parent reports: χ2 = 1643.812, df = 1129, RMSEA = .026, SRMR = .064, CFI = .920). In the third set of models, factor loadings and intercepts were constrained for similar items over time (i.e., scalar invariance: for teacher reports: χ2 = 2371.052, df = 1404, RMSEA = .030, SRMR = .069, CFI = .893; for parent reports: χ2 = 1742.41, df = 1179, RMSEA = 0.027, SRMR = 0.066, CFI = 0.913). Using ΔCFI < −.01 to establish measurement invariance (see Cheung & Rensvold, 2001) the results indicated that teacher reports exhibited metric invariance (ΔCFI = −.008) and parent reports exhibited scalar invariance (ΔCFI = −.007). Model comparisons were also used to assess measurement models for parents who completed the SDQ in English compared to those who completed the Spanish version. The results indicated that the SDQ exhibited scalar invariance (ΔCFI = −.008), thus this measure exhibited similar psychometric properties for the two versions.

Covariates

Academic performance was calculated using the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement Third Edition (WJ-III ACH; Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001). If children were more proficient in Spanish than in English, they were administered the comparable Spanish version of this test. A composite score for academic performance was created by first averaging the reading (consisting of letter-word identification, reading fluency, and passage comprehension) and broad math standard scores (consisting of calculations, math fluency, and math calculation skills) and then computing a standardized score. Extensive research documents the reliability and validity of these measures to assess children’s academic performance (Woodcock et al., 2001).

Annually, information was collected pertaining to whether children were retained in school (i.e., repeated the same grade level). Overall, approximately 33% of children were retained at some point, with grade retention primarily occurring in the earlier grades (i.e., 21.4% were retained in grade 1, 5.0% in grade 2, 4.0% in grade 3, 3.7% in grade 4, 1.2% in grade 5, and 1.3% in grade 6). To assess the effects of grade retention, a dichotomized variable was created (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Based on both school records and parents’ reports, family socioeconomic adversity was calculated as the mean of the standardized scores on five domains: (a) eligibility for free or reduced lunch, (b) single parent status, (c) rental status, (d) occupational level of any adult in the home (coded 1–9; e.g., 9 = farm laborers/menial service workers; 5 = clerical and sales work; 1 = higher executives, proprietors of large businesses), and (e) highest education level of any adult in the home (reverse coded).

Race and ethnicity were assessed as mutually exclusive categories. Two dichotomized variables were created reflecting children who indicated being either African American (0 = no, 1 = yes) or Hispanic or Latino (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Data Analysis Plan

The analysis plan for this study consisted of several aims. First, preliminary analyses assessed patterns of missing data and descriptive statistics. Second, growth mixture modeling (GMM) was performed to examine patterns of stability and change in children’s conflict and warmth trajectories and to identify distinct and heterogeneous trajectory classes from Grades 1 to 12. Third, the individual characteristics of children in each of the conflict and warmth trajectory classes were assessed by examining a set of potential covariates including gender, ethnicity, race, socioeconomic status, early conduct problems, early academic skills, and grade retention. Fourth, conditional latent growth models were used to examine the development of conduct problems based on children’s conflict and warmth trajectories. Analyses were performed using Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Because of the nested data structure (i.e., children nested within classrooms within schools), the type = complex command was used in Mplus to reduce potential biases in standard errors that could arise as a result of data non-independence.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Missing data analyses

An examination of missing data and participant attrition revealed that for all study variables attrition increased with the passage of time. To assess whether there were any observable or systematic patterns of missing data, a series of univariate t-tests were performed to examine the associations among children’s gender, race, ethnicity, socio-economic adversity, early academic performance, and grade retention on rates of missing data over time. With respect to the teacher-reported data on teacher-student relationship quality and conduct problems, the results indicated that none of these variables were systematically associated with participant attrition or missing data. With respect to the parent-reported data on conduct problems, the analyses indicated that lower early academic performance, socioeconomic adversity, and being Hispanic were associated with greater rates of missing data over time. Missing data were handled in Mplus using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation. This approach is advantageous compared to more traditional missing data techniques because it includes all participants in the analyses regardless of whether they had missing data or dropped out of the study (Enders, 2010). For FIML to provide accurate and unbiased parameter estimates, observable causes of missing data should be included within the specified models. Consequently, the specified models included ethnicity, early academic performance, and socioeconomic adversity as covariates to help meet this condition.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for study variables are reported in Table 1. Overall, rates of teacher-child warmth were high and exhibited a gradual decline over time (M = 4.01 in Grade 1 and M = 3.49 in Grade 12, with scores ranging from 1 to 5). Rates of teacher-child conflict were relatively lower and also exhibited a gradual decline over time (e.g., M = 1.88 in Grade 1 and M = 1.47 in Grade 12, with possible scores ranging from 1 to 5). Overall rates of parent- and teacher-reported conduct problems were comparable and exhibited declines over time (for parent reports: M = 2.03 in Grade 1 and M = 1.20 in Grade 12; for teacher-reports: M = 1.83 in Grade 1, M = 1.01 in Grade 12, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 10).

Developmental Trajectories of Teacher-Student Warmth and Conflict

To identify distinct developmental trajectories (classes) of teacher-student warmth and conflict from Grades 1 to 12, growth mixture models (with 2- thru 6-classes) were specified. These models were specified as piecewise models with one intercept and two slope (growth) factors to account for potential variations in children’s trajectories in primary and secondary school. More specifically, one slope factor measured growth trends from Grades 1 to 5 and the second slope factor measured growth from Grades 6 to 12. The rationale for selecting these grade ranges was based on school transition data which indicated that essentially all children made the transition to middle or junior high school beginning in Grade 5 or 6 (24% and 75%, respectively), with the majority making the transition in Grade 6.

To determine the optimal number of trajectory classes, multiple fit indices were evaluated in addition to examining whether the trajectory classes appeared substantively and conceptually meaningful (Ram & Grimm, 2009). Fit indices consisted of a combination of multiple information criteria (AIC, BIC, and sample-size adjusted BIC or SABIC), the likelihood ratio test (i.e., Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test; LMR-LRT), and classification accuracy. Models with smaller AIC, BIC, and SABIC values indicate better solutions. A significant p value on the LMR-LRT indicates that a model with k classes has better fit to the observed data than a model with k – 1 classes. Classification accuracy was assessed by examining the entropy and class assignment probabilities for each model (with values closer to 1 indicating more precise classification).

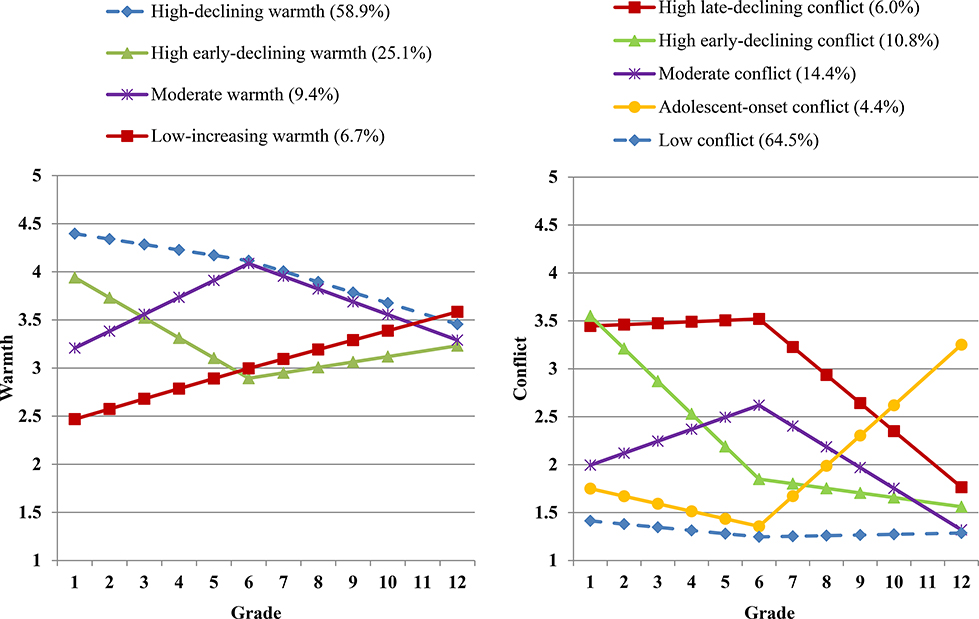

The first set of models examined developmental trajectories of teacher-student warmth from Grades 1 to 12. Fit indices for the models with varying classes are reported in Table 2. The 5-class solution had the lowest BIC, and the 4-class solution had the second lowest BIC. The AIC and SABIC decreased as the number of classes increased, thus favoring a 6-class solution. The LMR-LRT favored the 2-class solution, and the entropy values were comparable between the 2- to 4-class solutions but appeared to decline in the 5- and 6-class solutions. Taken together, the fit indices did not consistently identify an optimal solution. Thus, it was imperative to plot models with varying classes in order to assess their interpretability. Results indicated that the 4-class model yielded four distinct and conceptually meaningful classes. Comparing the 4- and 5-class solutions, four of the identified classes were similar in both models, however, the additional class identified in the 5-class solution was not very distinguishable from the other identified classes (i.e., this model identified two trajectory classes with high initial rates of warmth that declined over time). Thus, the 4-class solution was selected as a more parsimonious model. The 4-class model (see Figure 1) consisted of 58.9% of children with initially high warmth trajectories that steadily declined over time (labelled high-declining), 25.1% of children with initially high warmth trajectories that exhibited a sharp decline in elementary school (labelled high early-declining), 9.4% with initially moderate trajectories that increased in primary school and subsequently decreased in secondary school (labelled moderate), and 6.7% with initially low warmth trajectories that steadily increased over time (labelled low-increasing).

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Models Examining Teacher-Student Warmth and Conflict Trajectories in Grade 1 to 12

| Model | LogL | AIC | BIC | SABIC | Entropy | LMR-LRT | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warmth | |||||||

| 2-Class | −6850.72 | 13737.44 | 13821.31 | 13764.15 | 0.71 | 579.86 | < .001 |

| 3-Class | −6800.56 | 13645.12 | 13747.63 | 13677.77 | 0.70 | 96.69 | 0.10 |

| 4-Class | −6778.28 | 13608.56 | 13729.70 | 13647.13 | 0.69 | 42.96 | 0.22 |

| 5-Class | −6759.81 | 13579.62 | 13719.40 | 13624.13 | 0.61 | 35.60 | 0.33 |

| 6-Class | −6751.86 | 13571.71 | 13730.13 | 13622.16 | 0.58 | 15.33 | 0.56 |

| Conflict | |||||||

| 2-Class | −6532.31 | 13100.62 | 13184.49 | 13127.33 | 0.89 | 1443.30 | < .001 |

| 3-Class | −6394.94 | 12833.87 | 12936.37 | 12866.51 | 0.85 | 264.81 | 0.15 |

| 4-Class | −6325.13 | 12702.25 | 12823.39 | 12740.83 | 0.84 | 134.57 | 0.27 |

| 5-Class | −6273.25 | 12606.50 | 12746.28 | 12651.01 | 0.83 | 100.00 | 0.29 |

| 6-Class | −6226.08 | 12520.17 | 12678.58 | 12570.62 | 0.82 | 90.92 | 0.28 |

Note. LogL = Loglikelihood, AIC = Akaike information criteria, BIC = Bayesian information criteria, SABIC = Sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criteria; LMR-LRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test. G = grade. Class solutions highlighted in bold were selected as the optimal model for each set of analyses.

Figure 1.

Developmental trajectories (and class percentages) for teacher-student warmth and conflict from grades 1 to 12.

The second set of models examined developmental trajectories of teacher-student conflict from Grades 1 to 12. Comparing models with varying numbers of classes, the model fit indices indicated that the AIC, BIC and SABIC all decreased as the number of classes increased. However, comparing the 5- and 6-class models, it appeared that the additional class (in the 6-class model) was not conceptually distinct from the classes that were identified in the 5-class model, therefore the 5-class model appeared to be more parsimonious. The 5-class model (see Figure 1) consisted of 6.0% of children with initially high conflict trajectories that were stable in elementary school but declined in secondary school (labelled high late-declining), 10.8% with initially high conflict trajectories that exhibited a sharp decline in elementary school (labelled high early-declining), 14.4% with initially moderate trajectories that increased in primary school and subsequently decreased in secondary school (labelled moderate), 64.5% with initially low and stable trajectories (labelled low), and 4.4% with initially low levels of conflict in primary school which increased in secondary school (labelled adolescent-onset).

Early Childhood Characteristics Associated with Teacher-Student Warmth and Conflict Trajectories

We examined the individual characteristics (i.e., gender, ethnicity, race, socioeconomic adversity, early conduct problems, early academic performance, and grade retention) among the identified trajectory classes. These variables were assessed at Grade 1 as predictors of the trajectory classes. Effects were estimated using multinomial logistic regression and interpreted as odds ratios (OR). This approach allowed for an examination of potential additive effects (i.e., a simultaneous examination of multiple main effects in one model controlling for the effects of other variables). Because the introduction of additional variables (i.e., predictors) can impact the nature of the trajectory classes that are identified and class assignments, methodologists have recommended the 3-step approach which estimates these effects without having them influence class membership (Vermunt, 2010). Accordingly, the R3step function was used in Mplus (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014).

Using the high-declining warmth trajectory class as the reference group, the results (see Table 3) indicated that teacher-reported conduct problems increased the likelihood of being in the moderate, high early-declining and low-increasing warmth trajectory classes. Furthermore, boys had increased odds of being in the moderate and high early-declining classes, and African American children were highly unlikely to be in the moderate class. All other effects were not statistically significant (at p < .05).

Table 3.

Odds Ratios Examining Effects of Early Childhood Characteristics (in Grade 1) on Teacher-Child Warmth and Conflict Trajectories from Grades 1 to 12

| Trajectory class | Conduct problems (TR) | Conduct problems (PR) | Academic performance | Gender (male) | African American | Hispanic | Socioeconomic adversity | Grade retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate warmth | 2.20* | 1.23 | 0.73 | 6.84* | 0.00*** | 0.14 | 2.20 | 2.26 |

| High early-declining warmth | 1.63*** | 1.21 | 1.18 | 3.77** | 3.02 | 0.39 | 1.63 | 0.38 |

| Low-increasing warmth | 3.30*** | 1.23 | 0.98 | 0.77 | 22.33 | 1.75 | 0.20 | 0.93 |

| High late-declining conflict | 2.80** | 1.39 | 0.84 | 6.56* | 13.40 | 0.08 | 1.69 | 0.30 |

| High early-declining conflict | 3.02** | 1.04 | 1.76 | 1.73 | 4.86 | 0.50 | 0.71 | 3.61 |

| Adolescent-onset conflict | 1.60 | 0.86 | 1.16 | 4.88* | 2.60 | 0.24* | 2.07 | 1.20 |

| Moderate conflict | 1.35* | 1.06 | 0.81 | 9.99*** | 2.80* | 0.63 | 2.28* | 2.17* |

Notes: TR = teacher report; PR = parent report. The high-declining warmth and low conflict trajectory classes were used as the reference groups in their respective models.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

The results pertaining to the teacher-student conflict trajectories (see Table 3) indicated that compared to the low conflict trajectory class, teacher-reported early conduct problems increased the likelihood of being in the high late- and early-declining and moderate conflict trajectory classes. Boys were more likely to be in the high late-declining, moderate, and adolescent-onset classes. African American children were more likely to be in the moderate conflict class, and Hispanic children were less likely to be in the adolescent-onset class. Socioeconomic adversity and grade retention increased the odds of being in the moderate conflict class.

Children’s Conduct Problems and Teacher-Student Relationship Quality

The final set of analyses assessed the dynamic and co-occurring longitudinal associations between children’s conflict and warmth trajectories with their conduct problems. Conditional piecewise latent growth models were specified to examine continuity and changes in children’s conduct problems. All models were specified with one intercept and two slope (growth) factors, such that one slope factor measured changes in conduct problems from Grades 1 to 5 and the second slope factor measured changes from Grades 6 to 12. Class assignments derived from the conflict and warmth trajectory analyses were used to compute a series of dummy coded grouping variables that were then regressed on the latent intercept and slope factors. The low conflict and high-declining warmth trajectories served as the reference groups in their respective models. Models were specified three times by adjusting the intercept to estimate group differences in children’s conduct problems in Grades 1, 6, and 12. Notably, adjusting the intercept in these models did not change model fit or the form of the trajectory that was estimated. Fit for all growth models was deemed adequate if RMSEA < .06, and SRMR < .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Because software packages may use an inappropriate baseline model to compute the CFI in growth curve models (Wu, West, & Taylor, 2009), this index was not interpreted for these models. In addition to examining the effects of children’s conflict and warmth trajectories, these models also controlled for gender, ethnicity, race, socioeconomic status, early academic performance, and grade retention. With the inclusion of covariates, there were more parameter estimates than clusters in the models. To ensure that this did not introduce errors in the estimation of the standard errors, a comparison was made across models which included and excluded controlling for clustering (i.e., type = complex command). Results indicated that the estimated standard errors and significance tests were similar across these models.

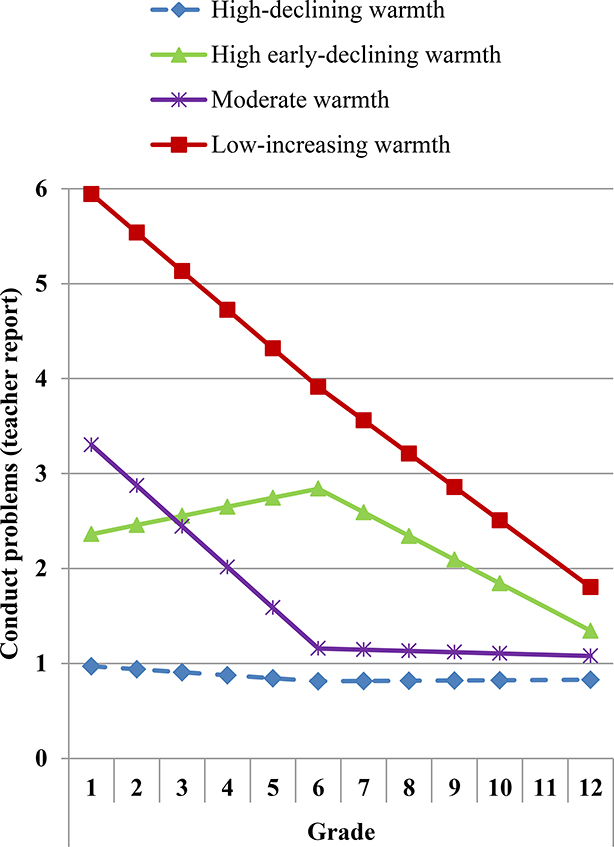

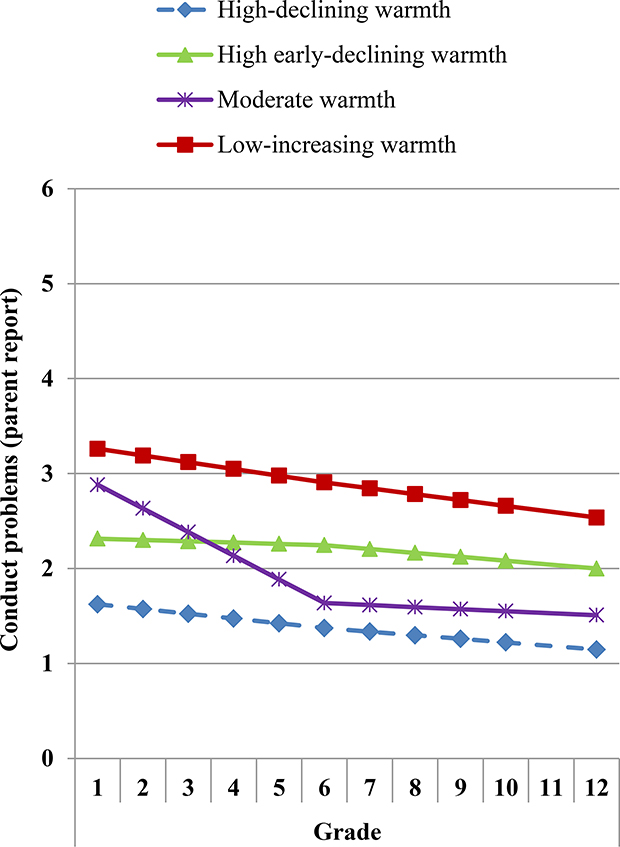

Estimates and significance tests for the teacher-student warmth trajectory groups and conduct problems are reported in Table 4 and illustrated for interpretative purposes in Figure 2. Compared to the high-declining warmth group (i.e., the reference group), the low-increasing warmth group had significantly higher levels of teacher- and parent-reported conduct problems in Grades 1, 6, and 12. Slope effects indicated that children in this group had a significant decline in conduct problems from Grades 1 to 5 and 6 to 12, but only for teacher-reports. The moderate warmth group also had significantly higher (teacher- and parent-reported) conduct problems in Grade 1, but not in Grades 6 or 12. Consistent with this pattern, the slope effects indicated that the moderate warmth group had a significant decrease in (teacher- and parent-reported) conduct problems in Grades 1 to 5. Finally, the high early-declining warmth group had significantly higher levels of conduct problems (teacher- and parent-reported) in Grades 1, 6, and 12. However, the slope effects (for teacher-reports) indicated that this group exhibited a significant increase in conduct problems in Grades 1 to 5, followed by a decrease in Grades 6 to 12.

Table 4.

Estimates for Conditional Growth Models Examining Children’s Conduct Problems by Teacher-student Warmth Trajectory Class

| Conduct problems (parent reports) | Conduct problems (teacher reports) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects | Est | SE | p | Est | SE | p |

| Grade 1 | ||||||

| Moderate warmth | 1.26 | 0.28 | *** | 2.33 | 0.27 | *** |

| High early-declining warmth | 0.69 | 0.18 | *** | 1.39 | 0.17 | *** |

| Low-increasing warmth | 1.64 | 0.34 | *** | 4.97 | 0.33 | *** |

| Grade 6 | ||||||

| Moderate warmth | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.21 | ||

| High early-declining warmth | 0.87 | 0.17 | *** | 2.03 | 0.17 | *** |

| Low-increasing warmth | 1.54 | 0.39 | *** | 3.10 | 0.44 | *** |

| Grade 12 | ||||||

| Moderate warmth | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.26 | ||

| High early-declining warmth | 0.85 | 0.24 | *** | 0.52 | 0.22 | * |

| Low-increasing warmth | 1.39 | 0.49 | ** | 0.98 | 0.49 | *** |

| G1-G5 slope | ||||||

| Moderate warmth | −1.99 | 0.54 | *** | −3.97 | 0.58 | *** |

| High early-declining warmth | 0.36 | 0.38 | 1.27 | 0.45 | ** | |

| Low-increasing warmth | −0.21 | 0.87 | −3.75 | 1.05 | *** | |

| G6-G12 slope | ||||||

| Moderate warmth | 0.16 | 0.43 | −0.16 | 0.48 | ||

| High early-declining warmth | −0.03 | 0.40 | −2.52 | 0.46 | *** | |

| Low-increasing warmth | −0.24 | 0.84 | −3.54 | 1.15 | ** | |

Notes: G = grade. The high-declining warmth trajectory class was used as the reference group. These models also included effects for gender, ethnicity, race, socioeconomic status, early academic performance, and grade retention, however these estimates are not reported in the table to simplify the presentation of results.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Figure 2.

Children’s predicted conduct problems by teacher-student warmth trajectory classes

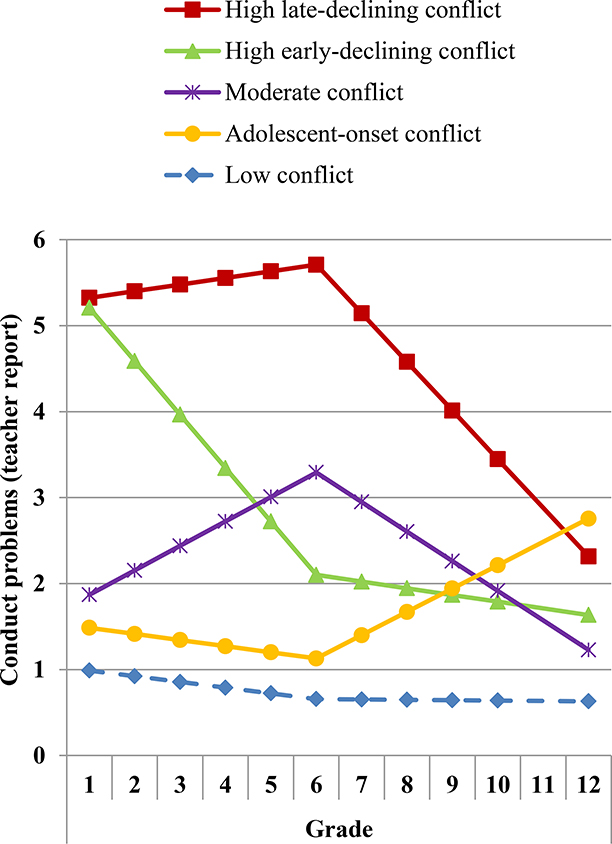

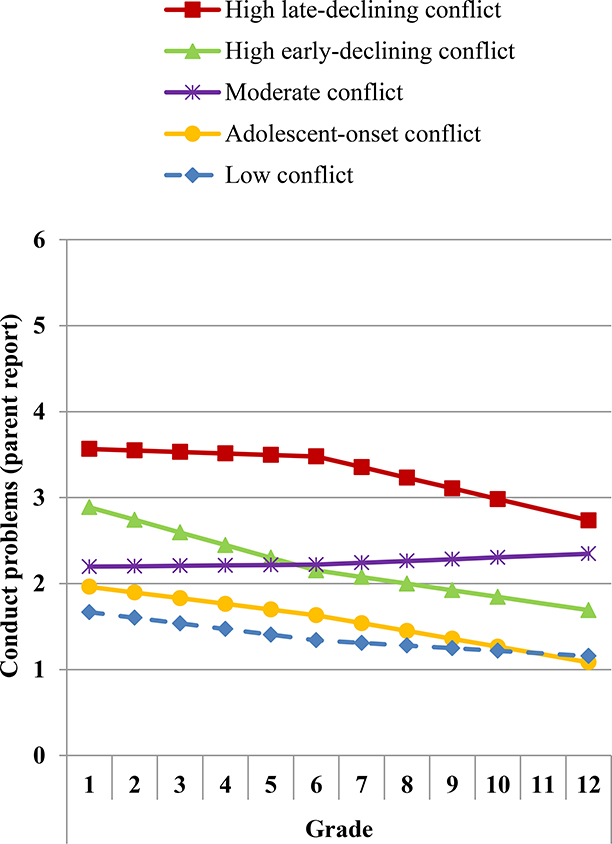

Associations among the teacher-student conflict trajectory groups and conduct problems are reported in Table 5 and illustrated in Figure 3. Compared to the low conflict group (i.e., the reference group), the high late-declining conflict group had significantly higher levels of conduct problems (teacher- and parent-reported) in Grades 1, 6, and 12. Slope effects indicated that children in this group had a significant decline in conduct problems from Grades 6 to 12, but only for teacher-reports. The moderate conflict group also had significantly higher levels of conduct problems (teacher- and parent-reported) in Grades 1, 6, and 12. However, the slope effects indicated that the moderate group exhibited a significant increase in teacher-reported conduct problems in Grades 1 to 5, followed by a significant decrease in Grades 6 to 12. The adolescent-onset conflict group had significantly higher teacher-reported conduct problems in Grade 12 (but not in Grades 1 or 6), and consistent with this pattern, the slope effects indicated that there was a significant increase in conduct problems in Grades 6 to 12. However, group differences for the adolescent-onset group were not significant with respect to parent-reports. Finally, the high early-declining conflict group had significantly higher levels of conduct problems (teacher- and parent-reported) in Grades 1, 6, and 12; however, the slope effects indicated that children in this group had a significant decline in teacher-reported conduct problems in Grades 1 to 5.

Table 5.

Estimates for Conditional Growth Models Examining Children’s Conduct Problems by Teacher-student Conflict Trajectory Class

| Conduct problems (parent reports) | Conduct problems (teacher reports) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects | Est | SE | p | Est | SE | p |

| Grade 1 | ||||||

| High late-declining conflict | 1.90 | 0.40 | *** | 4.34 | 0.35 | *** |

| Moderate conflict | 0.53 | 0.22 | * | 0.88 | 0.19 | *** |

| Adolescent-onset conflict | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.50 | 0.30 | ||

| High early-declining conflict | 1.22 | 0.25 | *** | 4.22 | 0.25 | *** |

| Grade 6 | ||||||

| High late-declining conflict | 2.14 | 0.38 | *** | 5.05 | 0.34 | *** |

| Moderate conflict | 0.88 | 0.21 | *** | 2.64 | 0.17 | *** |

| Adolescent-onset conflict | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.28 | ||

| High early-declining conflict | 0.81 | 0.26 | ** | 1.44 | 0.22 | *** |

| Grade 12 | ||||||

| High late-declining conflict | 1.58 | 0.45 | *** | 1.69 | 0.46 | *** |

| Moderate conflict | 1.19 | 0.32 | *** | 0.60 | 0.26 | * |

| Adolescent-onset conflict | −0.07 | 0.37 | 2.13 | 0.49 | *** | |

| High early-declining conflict | 0.53 | 0.25 | * | 1.01 | 0.32 | ** |

| G1-G5 slope | ||||||

| High late-declining conflict | 0.48 | 0.91 | 1.44 | 1.04 | ||

| Moderate conflict | 0.70 | 0.49 | 3.51 | 0.50 | *** | |

| Adolescent-onset conflict | −0.01 | 0.70 | −0.05 | 0.89 | ||

| High early-declining conflict | −0.81 | 0.56 | −5.55 | 0.58 | *** | |

| G6-G12 slope | ||||||

| High late-declining conflict | −0.94 | 0.80 | −5.61 | 1.04 | *** | |

| Moderate conflict | 0.51 | 0.57 | −3.40 | 0.56 | *** | |

| Adolescent-onset conflict | −0.61 | 0.75 | 2.76 | 0.92 | ** | |

| High early-declining conflict | −0.47 | 0.42 | −0.73 | 0.64 | ||

Notes: G = grade. The low conflict trajectory class was used as the reference group. These models also included effects for gender, ethnicity, race, socioeconomic status, early academic performance, and grade retention, however these estimates are not reported in the table to simplify the presentation of results.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Figure 3.

Children’s predicted conduct problems by teacher-student conflict trajectory classes

As previously indicated, all of the models also controlled for gender, ethnicity, race, socioeconomic status, early academic performance, and grade retention. With respect to the parent-reported conduct problems, the results indicated that boys had significantly higher rates of conduct problems in Grade 1 (b = .39, p < .01 in warmth model and b = .32, p = .03 in conflict model), but gender differences were attenuated across time. Hispanic children had higher rates of conduct problems in Grade 1 (b = .42, p = .01 in warmth model and b = .46, p < .01 in conflict model), but these effects were non-significant in Grades 6 and 12. Socioeconomic adversity was significantly associated with conduct problems in Grades 1, 6 and 12 (bs ranged from .30 to .48, p < .01). With respect to teacher-reported conduct problems, African American children had higher rates of conduct problems in Grades 1 and 6 (bs ranged from .34 to .63, p < .05). Socioeconomic adversity was significantly associated with conduct problems in Grades 1 and 12 (bs ranged from .21 to .40, p < .05). Low academic performance was associated with conduct problems in Grade 1 (b = −.15, p = .03 in warmth model and b = −.23, p < .001 in conflict model).

Discussion

This study makes several novel contributions to extant research on TSR. We were able to map variations (i.e., individual differences) in the development of TSR across a longer developmental period than previously examined, which provided new insights into the long-term development of TSR across the formal schooling years as children experienced multiple classroom and school transitions. Towards this end, the findings contribute to our understanding of the continuities and changes in TSR before and after the middle school transition. Although the transition to middle school is a dynamic period, the majority of children who were characterized as having low conflict trajectories exhibited patterns indicative of continuity as they made this transition to secondary schools. However, for the majority of children who were characterized as having high-declining warmth trajectories, it appeared that their rates of decline intensified in secondary school. Perhaps the most novel contribution of the current study was to chart the continuity and changes in conduct problems across Grades 1 to 12, based on differences in children’s relationship trajectories. Findings elucidated how the duration, magnitude, and timing of children’s relationship trajectories were associated with differential growth patterns in conduct problems. More specifically, relationships characterized by early-onset deficits, chronic and persistent relationship difficulties, or adolescent-onset conflict were associated with variations in the development of children’s conduct problems throughout childhood and adolescence. Finally, the findings have implications for better understanding the development of TSR and their long-term associations with children’s conduct problems among children who are racially and ethnically diverse, primarily low-income, and who exhibited early academic risks (i.e., low early literacy skills).

Development of Teacher-Student Relationships

Teacher-student warmth

The findings revealed four distinct trajectory classes for teacher-student warmth. As hypothesized, the majority of children (roughly 59%) exhibited high initial rates of warmth in elementary school that declined as they progressed through school (i.e., a high-declining class). This developmental pattern was consistent with, and extends, findings from studies on low-risk and at-risk samples which have documented a normative decline in teacher-student warmth across the elementary and middle school years (Jerome et al., 2009; Wu & Hughes, 2015). Although the rate of decline was fairly steady over time, it became somewhat steeper in the secondary school grades. These findings imply that rates of teacher-student warmth continue to decline for most students in high school, even among those students who initially experienced warm relationships. One explanation for this trend is that the typical classroom context in middle and high schools, in which students have multiple teachers and larger classes, may afford fewer opportunities and time for students to form warm and close relationships with teachers. Alternatively, it is possible that secondary school students prioritize relationships with peers and rely less on adults for support. Considering that the sample examined in the current study was academically at risk, this developmental trend may be particularly concerning given its implications that at-risk students may rely less on teachers as they progress through formal schooling, even though they may benefit the most from having warm and supportive TSR (Baker et al., 2008; Bosman et al., 2018; McGrath & van Bergen 2015; Murray & Zvoch, 2011).

Roughly 1 in 4 children (25%) had high initial rates of warmth in Grade 1, which appeared to decline relatively quickly through elementary school (i.e., a high early-declining class). For these students, it appeared that the declining trend in warmth preceded their transition to middle school, and by the start of middle school, these students exhibited the lowest rates of warmth which remained low throughout high school. As previously noted, extant research on the developmental trajectories of TSR has focused on the elementary grades, thus limiting our ability to make direct comparisons with the findings reported by other investigators. Nonetheless, the developmental pattern this class exhibited was consistent with a class identified by O’Connor and colleagues (2012) who had examined a lower-risk sample from preschool through Grade 5. More specifically, these investigators identified a class consisting of 20% of children who exhibited high initial rates of teacher-student closeness that declined through elementary school.

Roughly 1 in 10 students (9%) were characterized by initially moderate rates of warmth which increased through elementary school and subsequently declined after the transition to middle school (i.e., a moderate class). Interestingly, the developmental trajectory of this class was quite distinct from the high-declining class in the elementary school years, but by the start of middle school, these two classes exhibited very similar trajectories. In large part, the identification of this class was consistent with prior research on TSR in elementary school. More specifically, findings from three studies which examined both low-risk and at-risk samples similarly identified a class (ranging from 12% to 15% of students) who exhibited a moderate-increasing warmth trajectory in elementary school (Bosman et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2012; Spilt et al., 2012). Extending these prior findings, it appears that students in this trajectory class may actually exhibit a ‘peak’ in their warmth in Grade 5, followed by a subsequent decline after the transition to middle school. Thus, students in this class appear susceptible to the middle school transition and may experience similar contextual challenges as children in the high-declining class (e.g., fewer opportunities and time to form warm relationships with teachers).

Finally, a small proportion of children (about 7%) exhibited persistently low warmth in elementary school, which steadily increased into secondary school (a low-increasing class). The developmental pattern exhibited by students in this class during the elementary school years was very consistent with a class identified by O’Connor and colleagues (2012), which consisted of 3% of children who exhibited stable-low teacher-student closeness from preschool through Grade 5. However, it is notable that children in this group had some modest improvements in warmth over time, which continued through secondary school. Indeed, by Grade 12, overall differences among the four classes in levels of teacher-student warmth were negligible.

Teacher-student conflict

The findings for teacher-student conflict revealed five distinct trajectory classes. As hypothesized, the majority of children (roughly 65%) exhibited low initial rates of conflict with teachers in the elementary school grades that remained stable as they progressed through secondary school (i.e., a low class). The identification of a stable low class is consistent with attachment perspectives, according to which children’s internal working models contribute to stability and continuity in their relationship quality over time (Pianta, 1999; Sabol & Pianta, 2012). Moreover, among three studies that examined conflict trajectories in elementary school (i.e., Bosman et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2012; Spilt et al., 2012), a stable low conflict class was identified in each study, consisting of 57% to 88% of children. Taken together, these findings imply that regardless of sampling variations across studies (e.g., differences in academic risk, income, socioeconomic status, ethnicity or race), the majority of children experience low levels of teacher-child conflict. With respect to developmental and contextual changes, children in this group did not appear to be significantly impacted by the transition to middle school and maintained persistently low conflict in subsequent grade levels.

The finding that most children have stable low levels of conflict throughout their formal schooling is also consistent with the premise that teacher-student conflict represents a maladaptive relational experience which disproportionately impacts a substantial minority of students. However, among students who experienced more conflictual relationships, there was considerable heterogeneity in their conflict trajectories. We identified four distinct trajectory patterns which revealed qualitative differences in maladaptive conflict experiences across childhood and adolescence. These differences were reflected by variations in the magnitude or severity of conflict, its chronicity (i.e., duration), and developmental timing.

Although roughly 1 in 6 children (17%) exhibited initially high rates of conflict in Grade 1, there were variations in the duration and continuity of their conflict. For some, there was a relatively rapid decline in conflict through elementary school (i.e., a high early-declining class), and by the transition to middle school, children in this class exhibited consistently low levels of conflict. For others, conflict with teachers persisted through elementary school and subsequently declined after the middle school transition (i.e., a high late-declining class). Thus, these children had a more maladaptive relational context characterized by chronic conflict, particularly in the elementary grades. To some degree, both of these developmental trajectories appear to be consistent with prior research. For instance, studies conducted on elementary school students have consistently identified a moderate/high-declining class, ranging from 5% to 20% of children (Bosman et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2012; Spilt et al., 2012). Moreover, Spilt and colleagues (2012) and O’Connor and colleagues (2012) also identified a class of children with chronic (high-stable) conflict in elementary school. Expanding on their findings, our results imply that even among children with chronic conflict in elementary school, there may be a subsequent decline after the middle school transition. Perhaps the changing classroom structure in secondary school may be beneficial to the extent that having multiple teachers and spending less time interacting with individual teachers may reduce opportunities for conflict.

In addition to students who experienced early-onset conflict, a relatively small group of students (roughly 4%) was identified who had initially low rates of conflict in elementary school but exhibited increasing levels of conflict through secondary school (i.e., an adolescent-onset class). For students in this class, the middle school transition reflected a period in which there was a sharp increase in conflict. Notably, the identification of an adolescent-onset conflict class appears to be rather novel. Considering that its identification necessitates a long-term longitudinal design that spans childhood and adolescence, this class has not been previously identified in studies focusing on the elementary grades. Moreover, the extent to which this trajectory class is unique to students who are academically at risk is unclear. Consequently, additional research is warranted to replicate and validate these findings in other populations.

The final trajectory class consisted of roughly 14% of children with relatively moderate levels of conflict. More specifically, children in this class exhibited a slight increase in conflict throughout the elementary grades, followed by a decrease in secondary school. The nature of this class appears to be rather consistent with several studies that have identified a low- or moderate-increasing conflict class in elementary school (Bosman et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2012; Spilt et al., 2012). However, what distinguishes the findings reported in the current study from those previously reported is that for students in this trajectory class, it appeared that the middle school transition reflected an important period in which their conflict with teachers subsided.

Early Childhood Characteristics Associated with Teacher-Student Warmth and Conflict Trajectories

To ascertain the individual (child) characteristics associated with the warmth and conflict trajectories, we investigated the effects of children’s gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic adversity, grade retention, early academic performance, and early conduct problems. Taken together, the results indicated that children’s early conduct problems and gender were significantly associated with multiple warmth and conflict trajectories. Race, ethnicity, socioeconomic adversity, and grade retention were less consistently associated with TSR, but some notable findings are discussed below.

Perhaps the most salient findings pertained to role of early conduct problems. With respect to warmth, when compared to the high-declining trajectory class, early (teacher-reported) conduct problems increased the likelihood of class membership in all of other identified trajectory classes. With respect to conflict, children’s early (teacher-reported) conduct problems were significantly associated with the high (late- and early-declining) and moderate conflict classes, but not with the adolescent-onset class. These findings support and extend a large body of evidence gleaned from both variable-centered (Nurmi, 2012) and person-centered studies. For instance, applying a similar person-centered methodology as the current study, Bosman and colleagues (2018) and Spilt and colleagues (2015) reported that early conduct problems were strongly associated with high-stable, high-decreasing, and low-increasing conflict trajectories in elementary school. Extending these prior findings, the results of the current study imply that higher rates of early conduct problems may have lasting associations with students’ warmth and conflict trajectories as they progress into secondary school.

The findings also indicated that boys had a greater likelihood of high early-declining and moderate warmth trajectories, as well as high late-declining, adolescent-onset, and moderate conflict trajectories. For the most part, these findings are consistent with extant evidence. Variable-centered studies have consistently demonstrated that, on average, boys have lower teacher-student warmth and higher conflict than girls (McGrath & Van Bergen, 2015). Moreover, Bosman and colleagues (2018) applied a similar person-centered methodology as the current study and reported that gender and externalizing problems were more strongly associated with closeness and conflict trajectories in elementary school, in comparison to children’s SES, ethnicity, or early verbal abilities. Thus, regardless of sampling differences across studies, gender remains a persistent risk factor across multiple developmental periods and over and above the effects of conduct problems. Although the gender effects were mostly consistent with expectations, it was unexpected that boys were not more likely to be in the low-increasing warmth class. The reasoning for this finding is unclear; however, it may be reflective of the stronger impact of conduct problems. That is, once conduct problems (and other covariates) were taken into account, gender differences may have become less pronounced in this group.

An examination of other demographic factors indicated that African American children and those with greater socioeconomic adversity were more likely to exhibit moderate conflict trajectories. With respect to race, it is also notable that the odds ratios in the other conflict classes were quite high, but not statistically significant. Although the reasoning for this pattern is unclear, these findings may reflect low statistical power (e.g., small frequencies of African American children in some of the identified trajectory classes). An alternative explanation is that the effects of race may have been less consistently associated with conflict once other factors such as conduct problems and gender were taken into account (Gallagher, Kainz, Vernon-Feagans, & White, 2013). Although extant findings on race and teacher-student conflict have been mixed and inconsistent (see Hamre et al., 2007; Murray & Murray, 2004; Saft & Pianta, 2001; Spilt et al., 2012; Spilt & Hughes, 2015), investigators have proposed several explanations for their presumed associations. There is evidence that relationship quality is impacted by teacher-student racial and ethnic similarities, such that Caucasian teachers are more likely than African American teachers to report conflict with African American students (McGrath & Van Bergen 2015; Saft & Pianta, 2001). Moreover, African American students are disproportionately disciplined for school conduct violations, have their academic skills underestimated by teachers, and are more likely to be referred or placed in special education (Bradshaw, Mitchell, O’Brennan, & Leaf, 2010). This differential treatment is likely to result from implicit biases which may also contribute to lower quality relationships with African American students. Furthermore, these processes may be exacerbated in youth who are academically at risk.