Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the toxicity of azithromycin in neonates, infants, and children.

Methods

A systematic review was performed for relevant studies using Medline (Ovid), PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, CINAHL, and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts. We calculated the pooled incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with azithromycin based on prospective studies (RCTs and prospective cohort studies) and analyzed the risk difference (RD) of ADRs between azithromycin and placebo or other antibiotics using meta-analysis of RCTs.

Results

We included 133 studies with 4243 ADRs reported in 197,675 neonates, infants, and children who received azithromycin. The safety of azithromycin as MDA in pediatrics was poorly monitored. The main ADRs were diarrhea and vomiting. In prospective non-MDA studies, the most common toxicity was gastrointestinal ADRs (938/1967; 47.7%). The most serious toxicities were cardiac (prolonged QT or irregular heart beat) and idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS). Compared with placebo, azithromycin did not show increased risk ADRs based on RCTs (risk difference − 0.17 to 0.07). The incidence of QT prolonged was higher in the medium-dosage group (10–30 mg/kg/day) than that of low-dosage group (≤ 10 mg/kg/day) (82.0% vs 1.2%).

Conclusion

The safety of azithromycin as MDA needs further evaluation. The most common ADRs are diarrhea and vomiting. The risk of the most serious uncommon ADRs (cardiac-prolonged QT and IHPS) is unknown.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00228-020-02956-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Azithromycin, Safety, Pediatrics, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Azithromycin is an acid-stable orally administered macrolide antimicrobial drug, structurally related to erythromycin [1]. Due to its broad antibacterial spectrum against Streptococcus pneumonia, Moraxella catarrhalis, and atypical pathogens, azithromycin has been used extensively for the treatment of pediatric infectious diseases and became one of the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in children [2–6]. During the last 20 years, azithromycin mass drug administration (MDA) has been used to control trachoma with over 700 million doses of azithromycin being prescribed to children in areas of active trachoma programs [7]. Recent large trials have suggested that periodical azithromycin MDA may reduce post-neonatal infant and child mortality [8]. However, the long-term rationale for mass antibiotic distribution for trachoma is still the subject of debate with concerns of potential toxicity with azithromycin in pediatrics [9, 10].

A systematic review that evaluated the tolerance or toxicity of azithromycin in children with asthma found that gastrointestinal adverse reactions such as nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal pain were the main adverse events [11]. Another systematic review of azithromycin use in neonates highlighted the risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS) [12]. This systematic review aims to evaluate the toxicity of azithromycin both as MDA or non-MDA in neonates, infants, and children from birth to 18 years old. This systematic review was proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO), as one of the systematic reviews in support of developing a guideline of azithromycin use in pediatrics to help national and international policymakers in determining the role of prophylactic azithromycin in reducing child mortality [10].

Methods

This systematic review conformed to the PRISMA statement and was registered on PROSPERO (CRD 42018112629) [13]. We have reported the methods of literature search, risk of bias assessment, data abstraction, and data analysis in the published protocol [14].

Search strategy and literature search

In brief, we performed a comprehensive search using Medline (Ovid), PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, CINAHL, and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts. We reported the search strategies for each database in the published protocol [14]. We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case–control studies, cross-sectional studies, case series, and case reports that included pediatric patients (aged from birth to 18 years old) using azithromycin as periodic MDA or as therapeutic agent for any disease till March 2019, and updated the search in September 2019. We had no restriction on language. We excluded editorials, conference abstracts, and reviews. We searched for adverse drug reactions (ADRs) reported in spontaneous reporting systems or safety communication announcements as planned. However, since none of the spontaneous reporting systems provided detailed information for individual ADRs (e.g., age of patient, dosage of azithromycin) and none of the announcements was based on evidence in patients younger than 16 years old, we did not present the result in this paper.

Data extraction and analysis

We abstracted study design, characteristic of patients, interventions, methods used for safety monitoring, and ADRs from the eligible studies. We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool to assess risk of bias in RCTs, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for case–control study and cohort studies, and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tools for case series, case reports, and analytical cross-sectional studies [15–17]. We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) to assess the certainty of body of evidence [18]. We categorized ADRs by systems according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Terminology (version 21.1) [19] and by frequencies according to the Council for International Organization of Medical Science (CIOMS) as very common (≥ 10%), common (≥ 1% and < 10%), uncommon (≥ 0.1% and < 1%), and rare (< 0.1%) [20]. When the primary study explicitly reported zero ADR or when the study had the capacity to detect the ADR but did not report any event, we counted it as a zero event [21].

We calculated the pooled incidence of ADRs associated with azithromycin based on RCTs and prospective cohort studies to determine the risk of individual ADRs [22, 23]. We categorized ADRs into those that needed specific investigations (e.g., “decreased white blood cells” needs to be detected by a blood test; “prolonged QT” needs to be detected by an electrocardiograph (ECG)) and those that could be observed without specific investigations (e.g., diarrhea, vomiting). We analyzed risk difference (RD) of ADRs between azithromycin and placebo or other antibiotics using meta-analysis of RCTs. We did not use relative risk (RR) or odds ratio (OR) as planned in the protocol, as one cannot use inverse-variance methods to calculate RR or OR, when the number of events is zero in either group. One can, however, still calculate RD [24].

We used chi-square test of contingency table to identify the difference of pooled incidence of ADRs between different dosage groups (≤ 10 mg/kg/day, 10–30 mg/kg/day, > 30 mg/kg/day). The number of studies in each category did not meet the criteria for conducting regression (at least 10 events per category of dependent variables and 10 events per category of independent variables).

Results

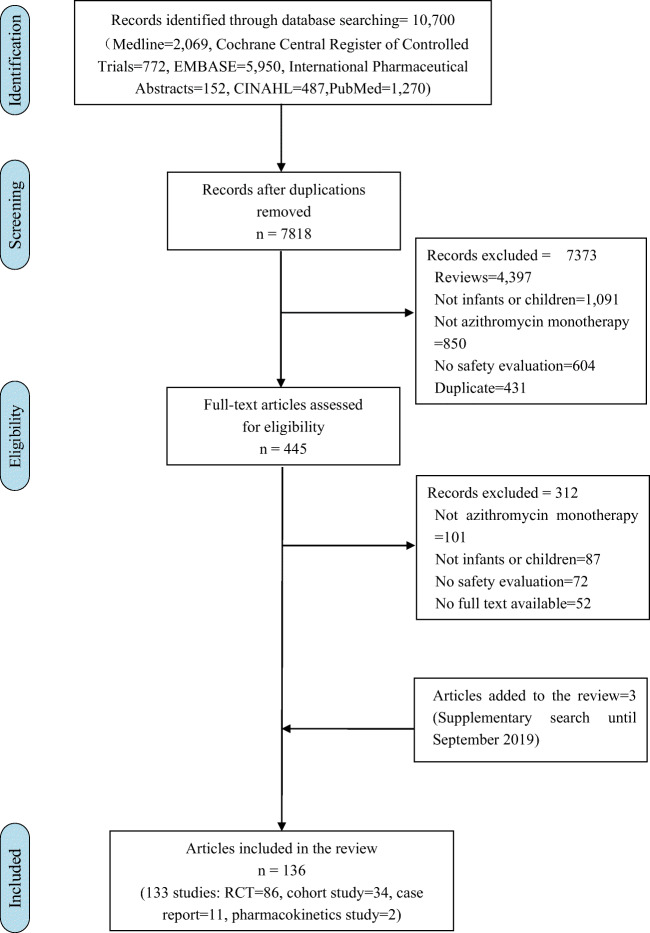

Of 10,700 titles identified, 445 proved potentially eligible after reviewing abstracts for the systematic reviews; 131 studies (133 articles) proved eligible following full text review. The updated search until September 2019 found two new trials (three articles) (Fig. 1). ESM Appendix 1 presents the characteristics of eligible studies. Risk of bias of individual RCTs was mainly due to unblinding of participants (high risk or unclear 65.1%, 56/86) or unblinding of outcome assessment (high risk or unclear 70.9%, 61/86). Risk of bias of individual cohort studies was mainly due to the lack of demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study (55.9%, 19/34) and the lack of comparability of cohorts (76.5%, 26/34) (ESM Appendix 2). Among all types of studies, 4243 ADRs were reported from 197,675 pediatric patients who received azithromycin. The majority of ADRs (56.1%, 2382/4243) were reported from RCTs not as MDA, 14.2% (603/4261) from retrospective cohort studies, and 6.5% (274/4243) from prospective cohort studies (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for screened articles

Table 1.

Summary of all articles

| Study type | Number of studies | Number of ADRs (%) | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCT not as MDA | 77 | 2382 (56.1) | 9830 (5.0) |

| Studies of MDA | 10* | 948 (22.3) | 154,180 (78.0) |

| Prospective cohort | 25 | 274 (6.5) | 2374 (1.2) |

| Retrospective cohort | 8** | 603 (14.2) | 31,209 (15.8) |

| Case report | 11 | 13 (0.3) | 12 (0.01) |

| Pharmacokinetics | 2 | 23 (0.5) | 70 (0.04) |

| Total | 133 | 4243 | 197,675 |

ADR, adverse drug reaction; MDA, mass drug distribution; RCT, randomized controlled trials

*Nine RCTs and one prospective cohort study

**One retrospective cohort study (n = 5039) focused on cardiac arrest in pediatric patients receiving azithromycin, and another retrospective cohort study (n = 15,073) focused on tendon or joint disorders

Azithromycin as MDA

We included eight RCTs and one prospective cohort study for azithromycin as MDA. Five RCTs reported no serious ADRs [25–29]. The incidence of ADRs was slightly higher in mass oral azithromycin communities compared with the untreated communities, and the most common ADRs were abdominal pain and vomiting in surveillance for adverse events during a large RCT [30]. The MORDOR study reported 11 cases of serious ADRs including 4 malaria, 1 respiratory infection, 1 ileus, 1 coma, and 4 deaths among 97,047 children through spontaneous reporting system reported by village informants and health facilities [31]. A cluster RCT of biannual mass azithromycin in Niger among preschool children found that the most common guardian-reported ADRs were diarrhea (110/571 in the azithromycin group, 321/1141 in the placebo group, P = 0.03), vomiting (91/571 in the azithromycin group, 240/1141 in the placebo group, P = 0.07), and rash (70/571 in the azithromycin group, 155/1141 in the placebo group, P = 0.07). This study found no statistically significant difference in the incidence of ADRs between azithromycin as MDA and placebo (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.10, P = 0.23) [32, 33]. A pilot cohort study in Ghana reported that 45 out of 14,548 children (0.3%) in azithromycin as MDA had mild to moderate self-limiting ADRs including abdominal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting reported by trained volunteers [34].

Azithromycin not as MDA

Prospective studies

For azithromycin administered not as MDA, a total of 1967 ADRs were reported in 10,132 patients from 63 RCTs and 22 prospective cohort studies. Gastrointestinal (GI) ADRs were most common, accounting for almost half of the ADRs (938/1967, 47.7%), followed by abnormal investigations (239/1967, 12.2%) and respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal ADRs (186/1967, 9.4%) (Tables 2 and 3). Diarrhea was the most common event among GI ADRs, accounting for 18.3% of all ADRs with a risk of 3.56 per 100 patients. Other common ADRs included vomiting (2.56 per 100 patients), abdominal pain (1.37 per 100 patients), and nausea (0.71 per 100 patients) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Risk of ADRs of azithromycin not as MDA from RCTs and prospective cohort studies (total number of participants = 10,132)

| ADRs | No. of events | Pooled incidence of ADRs per 100 participants |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||

| Diarrhea | 361 | 3.56 |

| Vomiting | 259 | 2.56 |

| Abdominal pain | 139 | 1.37 |

| Nausea | 72 | 0.71 |

| Loose stools | 69 | 0.68 |

| Abdominal pain upper | 19 | 0.19 |

| Flatulence | 6 | 0.06 |

| Stomachache | 6 | 0.06 |

| Gastrointestinal adverse event | 7 | 0.07 |

| Subtotal | 938 | |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | ||

| Cough | 75 | 0.74 |

| Nasal congestion | 46 | 0.45 |

| Pharyngolaryngeal pain | 29 | 0.29 |

| Rhinorrhoea | 25 | 0.25 |

| Cough productive | 11 | 0.11 |

| Subtotal | 186 | |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | ||

| Fever | 165 | 1.63 |

| Fatigue | 10 | 0.10 |

| Subtotal | 175 | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | ||

| Rash | 111 | 1.10 |

| Hives | 10 | 0.10 |

| Dermatitis | 8 | 0.08 |

| Fungal dermatitis | 5 | 0.05 |

| Subtotal | 134 | |

| Nervous system disorders | ||

| Headache | 49 | 0.48 |

| Dizziness | 7 | 0.07 |

| Somnolence | 6 | 0.06 |

| Subtotal | 62 | |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | ||

| Anorexia | 22 | 0.22 |

| Decreased appetite | 10 | 0.10 |

| Subtotal | 32 | |

| Immune system disorders | ||

| Jarisch–Herxheimer’s reaction | 13 | 0.13 |

| Subtotal | 13 | |

| Miscellaneous* | 102 | 1.01 |

| Total | 1642 | |

We excluded 14 RCTs and 3 prospective cohorts from the calculation of pooled incidences of ADRs due to the lack of detailed description of ADRs

ADR, adverse drug reaction; MDA, mass drug administrations

*ADRs with pooled incidence less than 5 per 100 participants

Table 3.

Risk of special ADRs of azithromycin not as MDA from RCTs and prospective cohort studies

| ARDs | No. of events | No. of studies | No. of participants | Pooled incidence of ARDs per 100 participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal investigations | ||||

| Increased eosinophils | 67 | 52 | 5278 | 1.27 |

| Decreased white blood cells | 52 | 53 | 5360 | 0.97 |

| Decreased neutrophils | 35 | 52 | 5278 | 0.66 |

| Increased glutamic-pyruvic transaminase | 31 | 50 | 5044 | 0.61 |

| Increased aspartate aminotransferase | 11 | 49 | 5009 | 0.22 |

| Thrombocytosis | 9 | 50 | 5120 | 0.18 |

| Abnormal liver function test | 8 | 51 | 5034 | 0.16 |

| Pulmonary function decreased | 14 | 5 | 448 | 3.13 |

| Increased white blood cell counts | 4 | 53 | 5361 | 0.07 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 | 50 | 5120 | 0.06 |

| Increased platelet count | 3 | 50 | 5120 | 0.06 |

| Pseudomonas test positive | 2 | 1 | 110 | 1.82 |

| Subtotal | 239 | |||

| Cardiac disorders | ||||

| Electrocardiogram QT prolonged* | 54 | 5 | 277 | 19.49 |

| Electrocardiogram QT shortened | 11 | 4 | 157 | 7.01 |

| Irregular heart beat | 10 | 2 | 157 | 6.37 |

| Elevated heart rate | 4 | 2 | 157 | 2.55 |

| Subtotal | 79 | |||

| Miscellaneous*** | 7 | 51 | 5154 | 0.14 |

| Total | 325 | |||

ADR, adverse drug reaction; MDA, mass drug administrations; RCT, randmised controlled trial

*Including borderline QT

**We excluded 14 RCTs and 3 prospective cohorts from the calculation of pooled incidences of ARDs for the lack of detailed description of ADRs

***ADRs that only has one event reported

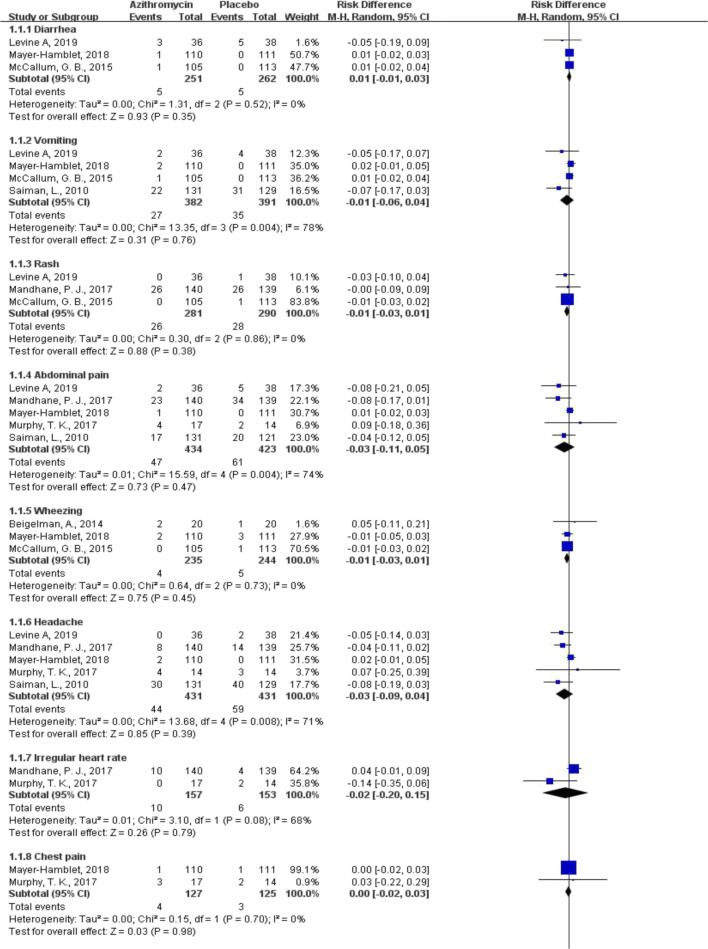

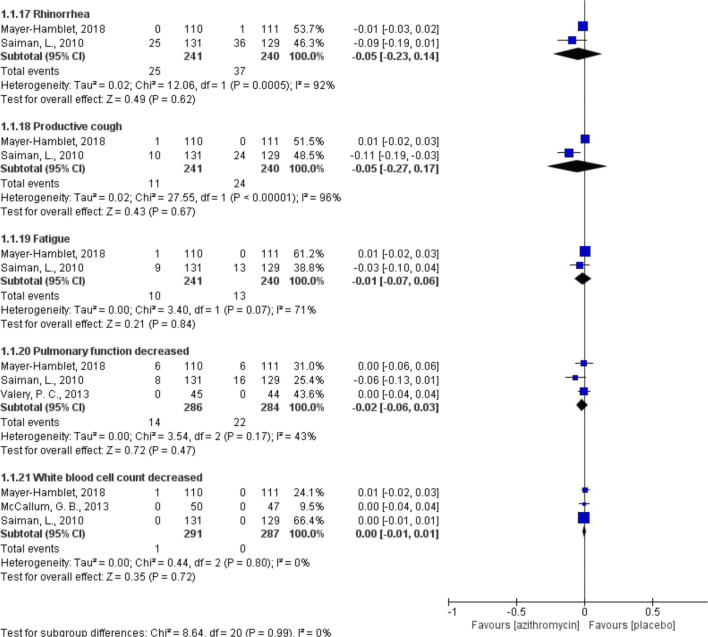

Compared with placebo, azithromycin showed no statistically significant difference in terms of incidence of ADRs (risk difference [RD] − 0.17 to 0.07; low to moderate certainty of evidence) (Fig. 2). Similar results were found when azithromycin was compared with cephalosporins and other macrolides (ESM Appendix 3). Azithromycin showed a decreased risk of diarrhea, when compared with amoxicillin/clavulanate (RD − 0.11, 95% CI − 0.15 to − 0.07, P < 0.001; low certainty of evidence), but an increased risk of diarrhea when compared with penicillin V (RD 0.03, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.05, P = 0.005; high certainty of evidence) (ESM Appendix 3). ESM Appendix 4 presents certainty of evidence of each pooled estimate.

Fig. 2.

Risk difference of ADRs between azithromycin not as MDA and placebo

Retrospective studies

Three hundred and six ADRs were reported in 31,221 patients from eight retrospective cohort studies and 11 case report studies (ESM Appendix 1). The ADRs reported in retrospective studies were generally consistent with those in prospective studies. GI ADRs were still the most common events accounting for 44.9% (145/323) of all ADRs, followed by musculoskeletal and connective tissue ADRs (36.5%, 118/323). However, some ADRs that were not detected in prospective studies were reported by retrospective studies including tendon or joint disorders (TJDs) (n = 118), infantile IHPS (n = 8), and ventricular tachycardias (n = 4). The full list is shown in ESM Appendix 4.

Cardiac toxicity

Most prospective studies in children did not evaluate the risk of cardiac toxicity. Cardiac toxicity was only studied or reported in eight studies (six prospective, one retrospective, and one case report). Among prospective studies, five RCTs and one prospective cohort study reported 79 cardiac adverse events (Table 4) [35–40]. One prospective study where children received weekly azithromycin for 6 months reported statistically significant QT prolongation [35]. QT prolongation was also noted in two other studies. Two studies reported irregular heart rates and two studies reported no adverse events. A retrospective cohort study that compared azithromycin (n = 5039) with penicillin or cephalosporin (n = 77,943) in pediatric patients found that the rate of cardiac arrest in the azithromycin group was lower than that of the penicillin or cephalosporin groups (0.04% vs 0.14%, P = 0.04) [41]. A case report described severe bradyarrhythmia in a 9-month-old infant who received over 50 mg/kg azithromycin intravenously over 20 min [42].

Table 4.

RCTs and prospective cohort studies that monitored cardiac ADRs

| Study ID | Study design | Cardiac ADRs | Incidence in the AZ group | Incidence in the control group | Who monitored the cardiac ADRs | Methods for monitoring cardiac ADRs | Severity of the cardiac ADRs | Duration of follow-up (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murphy T K 2017 | RCT | Heart beat irregular or pounding | 17.6%, 3/17 | Placebo 14.2%, 2/14 | Pediatric cardiologists | ECG in the AZ and control groups | Mild, no medication discontinuation | 28 |

| QT borderline | 11.8%, 2/17 | Placebo 0%, 0/14 | ||||||

| Elevated heart rate | 23.5%, 4/17 | Placebo 7.1%, 1/14 | ||||||

| Mandhane P J 2017 | RCT | Irregular heart rate | 7.1%, 10/140 | Placebo 2.9%, 4/139 | NR | ECG in the AZ and control groups | No serious or life-threatening adverse events | 35 |

| El Hennawi D E D 2017 | RCT | QT prolongation | 82.0%, 50/61 | Benzathine penicillin: not monitored | NR | ECG only in the AZ group | The mean of QT rose significantly from 41.6 + 1.7 ms before treatment to 43.8 + 2.9 ms (P = 0.007) after treatment in the AZ group | 180 |

| QT shortening | 18.0%, 11/61 | |||||||

| Mayer-Hamblett N 2018 | RCT | Prolongation of QTc | 1.8%, 2/110 | Placebo 6.3%, 7/111 | NR | ECG | No clinically significant prolongation of QTc |

AZ 11.5 ± 6.1 months Placebo 10.8 ± 6.3 months |

| Levine A 2019 | RCT | No cardiac ADR | 0%, 0/35* | Metronidazole 0%, 0/38 | Physician | ECG in the AZ and control groups | – | 56 |

| Liu S 2018 | Prospective cohort** | No cardiac ADR | 0%, 0/44 | – | Pediatric cardiologists | ECG in the AZ group | – | 10 |

AZ, azithromycin; ADR, adverse drug reaction; ECG, electrocardiograph; NR, not reported; RCT, randomized controlled trial

*AZ plus metronidazole

**Single-arm cohort

Pyloric stenosis

A retrospective cohort study utilized a large health system database and evaluated 1,074,236 children born over a period of 12 years [43]; 2466 infants developed IHPS and 4875 infants received azithromycin in the first 90 days of life and eight of these infants (all boys) developed IHPS. The study demonstrated an increased risk following exposure to azithromycin in the first 2 weeks of life (adjusted OR [aOR] of 8.26, 95% CI 2.62–26.0) [43]. Azithromycin exposure between 15 and 42 days also increased the risk of IHPS (aOR of 2.98, 95% CI 1.24–7.20).

Subgroup analysis of dosage

The incidence of diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and rash was higher in the high-dosage group compared with the low- or medium-dosage group (P < 0.01) (Table 5). The incidence of prolonged QT and increased eosinophils was higher in the medium-dosage group than in the low-dosage group (P < 0.01) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pooled incidence of ADRs from RCTs and prospective cohort studies in different dose groups

| ADRs | Low dosage (≤ 10 mg/kg) | Medium dosage (10–30 mg/kg) | High dosage (> 30 mg/kg) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADRs that did not need specific investigations* | ||||

| Diarrhea | 147 (2.5%)a | 85 (3.5%)a | 42 (9.3%)b | < 0.001 |

| Vomiting | 113 (1.9%)a | 65 (2.6%)a | 48 (10.7%)b | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 98 (1.7%)a | 28 (1.1%)a | 11 (2.4%)a | 0.059 |

| Fever | 9 (0.2%)a | 0 (0.0%)a | 7 (1.6%)b | < 0.001 |

| Rash | 73 (1.3%)a | 15 (0.6%)b | 23 (5.1%)c | < 0.001 |

| ADRs that needed specific investigation | ||||

| QT prolongedα | 4 (1.2%)a | 50 (82.0%)b | – | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary function decreasedβ | 14 (4.3%)a | 0 (0.0%)a | – | 0.10 |

| Increased eosinophilγ | 38 (0.9%)a | 31 (3.0%)b | – | < 0.001 |

There was no statistical difference between the two groups with the same letter a, b, or c in the following table. Otherwise, there is a statistical difference

ADR, adverse drug reaction; RCT, randomized controlled trial

*The total number of patients was 5811 in the low-dosage group, 2454 in the medium-dosage group, and 450 in the high-dosage group

Discussion

Our review found that the main toxicity of azithromycin in pediatrics was gastrointestinal toxicity, specifically diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Based on available data, the main ADRs of azithromycin as MDA were diarrhea and vomiting. However, the reporting of ADRs in RCTs of MDA was very variable. Concerns about the reporting of ADRs in RCTs involving children have been reported by several groups [44, 45]. For azithromycin not as MDA, our review highlighted that the most common toxicity was GI adverse reactions, and the most serious toxicities were cardiac adverse reactions and IHPS. The risk of cardiac toxicity and IHPS following MDA is unknown and can only be determined by prospective surveillance studies. The dose of azithromycin was associated with the risk of ADRs. The higher the dosage, the higher the risk of an ADR.

Our study has several strengths. Using rigorous systematic review methods, we did a comprehensive search of the literature and evaluated the safety of azithromycin as both MDA and not as MDA. Our review included recently published studies which were not included in prior reviews, and thus, summarized all of the available evidence, providing optimal insight into the safety of azithromycin in pediatrics. We assessed the risk of bias of each primary study using risk of bias assessment tools based on study design. We detected the incidence of adverse events based on prospective studies from which the data are more reliable, and explored uncommon events from the larger retrospective studies.

This review also has some limitations. First, the ADRs were poorly reported in primary studies which led to the probable underestimate of the incidence of ADRs in this review. Even the meta-analysis might still be underpowered to detect potential differences between azithromycin and placebo or other antibiotics. The lack of ADR reporting is more common in studies of azithromycin as MDA and we were unable to conclude the safety of azithromycin as MDA compared with placebo. Second, we did not perform analysis of different age groups as planned in the protocol since most primary studies did not report the outcomes for each age group separately.

To our knowledge, the ADRs of azithromycin as MDA in children have not been evaluated in previous systematic reviews [46]. For azithromycin not as MDA, cardiac toxicity of azithromycin has been a concern for a long time. Previous studies and reviews found the risk of azithromycin appears to depend on age and prior cardiovascular risk in adults. However, none of them evaluated the risk in pediatric patients. In our review, cardiac adverse events were found in pediatric patients, but the difference between the azithromycin group and the control group was not significant in most of the studies. Only one study found a statistically significant increase in QT prolongation, but this study involved weekly administration of azithromycin for 6 months and only children who received azithromycin received ECGs [35]. Additionally, the data from some studies must be questioned because the method for safety surveillance was poorly reported [26, 27, 35]. Future studies in pediatric patients should be conscious of using robust methods for safety monitoring.

Previous studies have demonstrated the association between erythromycin exposure early in life and IHPS [47–52]. Only one retrospective study was found in our review that evaluated the association between azithromycin and IHPS. Since azithromycin and erythromycin are slightly different in molecular structure, further studies are required to determine the relationship between early exposure to azithromycin in life and IHPS [12]. The risk of IHPS following MDA is unknown and should be considered in future studies of MDA. However, prospective surveillance following MDA with larger numbers of patients is more likely to be beneficial.

Conclusion

The main ADRs of azithromycin whether used as MDA or not were gastrointestinal, specifically diarrhea, abdominal pain, and vomiting. For azithromycin not as MDA, the most serious toxicities were cardiac adverse reactions and IHPS. Increasing dose proved to increase the risk of ADRs.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 22.3 kb)

(DOCX 21 kb)

(PDF 1044 kb)

(DOC 132 kb)

(DOCX 21.1 kb)

Author contributions

IC, LNZ, PPE, LLZ, TX, and SAQ designed the study. XCP, WYL, PPX, and XFN screened the literatures independently in two pairs. PPX, XCP, WYL, PPX, XFN, CC, and LSH abstracted data and cross-checked the data in pairs. LNZ and TX resolved discrepancies in literature screening and data abstraction. ZYB, LNZ, and PPX analyzed the data. LZN, PPX, and IC interpreted the data. LNZ, IC, TX, SAQ, DZM, and LLZ drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content and have given final approval of the version published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding information

This project was funded by the Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health of World Health Organization (WHO Registration 2018/859230-0) and Key Program of Science and Technology Agency, Sichuan Province (No. 2017JY0067).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Peters DH, Friedel HA, McTavish D. Azithromycin. Drugs. 1992;44:750–799. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199244050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laopaiboon M, Panpanich R, Swa MK. Azithromycin for acute lower respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD001954. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001954.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clavenna A, Bonati M. Differences in antibiotic prescribing in paediatric outpatients. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:590–595. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.183541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franchi C, Sequi M, Bonati M, Nobili A, Pasina L, Bortolotti A, Fortino I, Merlino L, Clavenna A. Differences in outpatient antibiotic prescription in Italy’s Lombardy region. Infection. 2011;39:299–308. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grijalva CG, Nuorti JP, Griffin MR. Antibiotic prescription rates for acute respiratory tract infections in US ambulatory settings. JAMA. 2009;302:758–766. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langtry HD, Balfour JA. Azithromycin. A review of its use in paediatric infectious diseases. Drugs. 1998;56:273–297. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199856020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emerson PM, Hooper PJ, Sarah V. Progress and projections in the program to eliminate trachoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keenan JD, Bailey RL, West SK, Arzika AM, Hart J, Weaver J, Kalua K, Mrango Z, Ray KJ, Cook C, Lebas E, O'Brien KS, Emerson PM, Porco TC, Lietman TM, MORDOR Study Group Azithromycin to reduce childhood mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1583–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaynor BD, Yi E, Lietman T. Rationale for mass antibiotic distribution for trachoma elimination. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2002;42:85–92. doi: 10.1097/00004397-200201000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Presumptive use of azithromycin. Guideline in development. Available at: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/guidelines/development/provision-of-azithromycin-to-infants/en/. Accessed 10 Feb 2020

- 11.Tian BP, Xuan N, Wang Y, Zhang G, Cui W. The efficacy and safety of azithromycin in asthma: a systematic review. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:1638–1646. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith C, Egunsola O, Choonara I, Kotecha S, Jacqz-Aigrain E, Sammons H. Use and safety of azithromycin in neonates: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008194. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu P, Zeng L, Xiong T, Choonara I, Qazi S, Zhang L. Safety of azithromycin in paediatrics: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2019;3:e000469. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2019-000469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: The Cochrane Library, Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D et al (2011) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 16 Jul 2020

- 17.Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical appraisal tools. Available at: https://joannabriggs.org/ebp/critical_appraisal_tools. Accessed 16 Jul 2020

- 18.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:382–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown EG, Wood L, Wood S. The medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA) Drug Saf. 1999;20:109–117. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199920020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neubert A, Dormann H, Prokosch HU, Bürkle T, Rascher W, Sojer R, Brune K, Criegee-Rieck M. E-pharmacovigilance: development and implementation of a computable knowledge base to identify adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(Suppl 1):69–77. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortese S. Guidance on conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of completed comparative pharmacoepidemiological studies of safety outcomes: the gap is now filled. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25:425–427. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egunsola O, Choonara I, Sammons HM. Safety of lamotrigine in paediatrics: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007711. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egunsola O, Choonara I, Sammons HM. Safety of levetiracetam in paediatrics: a systematic review. PlosOne. 2016;11:e0149686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Efthimiou O. Practical guide to the meta-analysis of rare events. Evid Based Mental Health. 2018;21:72–76. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amza A, Kadri B, Nassirou B, Stoller NE, Yu SN, Zhou Z, West SK, Mabey DCW, Bailey RL, Keenan JD, Porco TC, Lietman TM, Gaynor BD. A cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effects of mass azithromycin treatment on growth and nutrition in Niger. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:138–143. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West SK, Bailey R, Munoz B, Edwards T, Mkocha H, Gaydos C, Lietman T, Porco T, Mabey D, Quinn TC. A randomized trial of two coverage targets for mass treatment with azithromycin for trachoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melese M, Alemayehu W, Lakew T, Yi E, House J, Chidambaram JD, Zhou Z, Cevallos V, Ray K, Hong KC, Porco TC, Phan I, Zaidi A, Gaynor BD, Whitcher JP, Lietman TM. Comparison of annual and biannual mass antibiotic administration for elimination of infectious trachoma. JAMA. 2008;299:778–784. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.7.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Brien KS, Cotter SY, Amza A, et al. Childhood mortality after mass distribution of azithromycin: a secondary analysis of the PRET cluster-randomized trial in Niger. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37:1082–1086. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keenan JD, Gebresillasie S, Stoller NE, Haile BA, Tadesse Z, Cotter SY, Ray KJ, Aiemjoy K, Porco TC, Callahan EK, Emerson PM, Lietman TM. Linear growth in preschool children treated with mass azithromycin distributions for trachoma: a cluster-randomized trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayele B, Gebre T, House JI et al. Adverse events after mass azithromycin treatments for trachoma in Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:291–294. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keenan JD, Tadesse Z, Gebresillasie S, Shiferaw A, Zerihun M, Emerson PM, Callahan K, Cotter SY, Stoller NE, Porco TC, Oldenburg CE, Lietman TM. Mass azithromycin distribution for hyperendemic trachoma following a cluster-randomized trial: a continuation study of randomly reassigned subclusters (TANA II) PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oldenburg CE, Arzika AM, Maliki R, Kane MS, Lebas E, Ray KJ, Cook C, Cotter SY, Zhou Z, West SK, Bailey R, Porco TC, Keenan JD, Lietman TM, MORDOR Study Group Safety of azithromycin in infants under six months of age in Niger: a community randomized trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arzika AM, Maliki R, Boubacar N, Kane S, Cotter SY, Lebas E, Cook C, Bailey RL, West SK, Rosenthal PJ, Porco TC, Lietman TM, Keenan JD, for the MORDOR Study Group Biannual mass azithromycin distributions and malaria parasitemia in pre-school children in Niger: a cluster-randomized, placebo controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdulai AA, Agana-Nsiire P, Biney F, Kwakye-Maclean C, Kyei-Faried S, Amponsa-Achiano K, Simpson SV, Bonsu G, Ohene SA, Ampofo WK, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Addo KK, Chi KH, Danavall D, Chen CY, Pillay A, Sanz S, Tun Y, Mitjà O, Asiedu KB, Ballard RC. Community-based mass treatment with azithromycin for the elimination of yaws in Ghana-results of a pilot study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Hennawi DED, Geneid A, Zaher S, et al. Management of recurrent tonsillitis in children. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38:371–374. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy TK, Brennan EM, Johnco C, Parker-Athill EC, Miladinovic B, Storch EA, Lewin AB. A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled pilot study of azithromycin in youth with acute-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27:640–651. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayer-Hamblett N, Retsch-Bogart G, Kloster M, Accurso F, Rosenfeld M, Albers G, Black P, Brown P, Cairns AM, Davis SD, Graff GR, Kerby GS, Orenstein D, Buckingham R, Ramsey BW, Retsch-Bogart G, Accurso FJ, Buckingham R, Howenstine M, Jacob S, Kronmal R, Kuhn R, Mayer-Hamblett N, McCoy K, Nichols D, Ramsey BW, Rosenfeld M, Sagel S, Saiman L, Sheridan J, Wilfond B, Zemanick E, Bondick I, Braam L, Brassil M, Buckingham R, Cianciola M, Heltshe S, Jacob S, Johnson M, Kirihara J, Kloster M, Kong A, Ma S, McNamara S, Mann L, Moormann K, Myers M, Mayer-Hamblett N, Ramsey BW, Retsch-Bogart G, Seidel K, Skalland M, Ufret-Vincenty C, VanDalfsen J, Goss CH, Horne DJ, Kross EK, Leary PJ, Ramos KJ, Roush P, Salerno JC, Omlor G, Ouellette D, Green D, Hosler K, Savant A, Ashrafi Z, Berlinski A, Ross A, Sawicki G, Fowler R, Ulles M, Albers G, Branch F, Kirchner K, DiBenardo K, Kerby G, Anthony M, Keens T, Franquez A, Reyes C, Abdulhamid I, van Wagnen C, Orenstein D, Hartigan E, Mihlo C, Williams R, Lessard M, Sass L, McAndrews E, Parrott J, Noe J, Hastings P, Kump T, Clancy J, Niehaus S, Saiman L, Zhou J, Mueller G, Bartosik S, Fullmer J, Millian C, Stecenko A, Dangerfield J, Graff G, Kitch D, Cairns AM, Milliard C, Zanni R, Marra B, McCoy K, Guittar P, Smith M, Schaeffer D, DeLuca E, Welter J, Gallagher M, Ramirez A, Cornell A, Simeon E, Roberts D, Nelson K, Chmiel J, Schaefer C, Davis SD, Shively L, Wallace J, Richter A, Ramsey B, McNamara S, Pittman J, Hicks T, Brown P, Durham D, Milla C, Zirbes J, Fortner C, Suttmore V, Black P, Thompson R, Daines C, Varela M, Starner T, Teresi M, Nasr S, Kruse D, Thomas H, Houdesheldt L, Retsch-Bogart G, Barlow C, Cunnion R, Srinivasan S, Horobetz C, Asfour F, Francis J, Rock M, Makholm L, Egan M, Guzman C. Azithromycin for early pseudomonas infection in cystic fibrosis the OPTIMIZE randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1177–1187. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201802-0215OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandhane PJ, de Silbernagel PPZ, Aung YN, et al. Treatment of preschool children presenting to the emergency department with wheeze with azithromycin: a placebo-controlled randomized trial. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine A, Kori M, Kierkus J, Sigall Boneh R, Sladek M, Escher JC, Wine E, Yerushalmi B, Amil Dias J, Shaoul R, Veereman Wauters G, Boaz M, Abitbol G, Bousvaros A, Turner D. Azithromycin and metronidazole versus metronidazole-based therapy for the induction of remission in mild to moderate paediatric Crohn’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2019;68:239–247. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu S, Zheng Y, Wu X, Xu B, Liu X, Feng G, Sun L, Shen C, Li J, Tang B, Jacqz-Aigrain E, Zhao W, Shen A. Early target attainment of azithromycin therapy in children with lower respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:2846–2850. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valery PC, Morris PS, Byrnes CA, Grimwood K, Torzillo PJ, Bauert PA, Masters IB, Diaz A, McCallum GB, Mobberley C, Tjhung I, Hare KM, Ware RS, Chang AB. Long-term azithromycin for indigenous children with non-cystic-fibrosis bronchiectasis or chronic suppurative lung disease (Bronchiectasis Intervention Study): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:610–620. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tilelli JA, Smith KM, Pettignano R. Life-threatening bradyarrhythmia after massive azithromycin overdose. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:147–150. doi: 10.1592/phco.2006.26.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eberly MD, Eide MB, Thompson JL, Nylund CM. Azithromycin in early infancy and pyloric stenosis. Pediatrics. 2015;135:483–488. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson M, Choonara I. A systematic review of safety monitoring and drug toxicity in published randomised controlled trials of antiepileptic drugs in children over a 10-year period. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:731–738. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.165902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Vries TW, van Roon EN. Low quality of reporting adverse drug reactions in paediatric randomised controlled trials. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:1023–1026. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.175562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oldenburg CE, Arzika AM, Amza A, Gebre T, Kalua K, Mrango Z, Cotter SY, West SK, Bailey RL, Emerson PM, O’Brien KS, Porco TC, Keenan JD, Lietman TM. Mass azithromycin distribution to prevent childhood mortality: a pooled analysis of cluster-randomized trials. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;100:691–695. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.SanFilippo A. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis related to ingestion of erythromycine estolate: a report of five cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1976;11:177–180. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(76)90283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stang H. Pyloric stenosis associated with erythromycin ingested through breastmilk. Minn Med. 1986;69:669–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in infants following pertussis prophylaxis with erythromycin--Knoxville, Tennessee. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:1117–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Honein MA, Paulozzi LJ, Himelright IM, Lee B, Cragan JD, Patterson L, Correa A, Hall S, Erickson JD. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis after pertussis prophylaxis with erythromcyin: a case review and cohort study. Lancet. 1999;354:2101–2105. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)10073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahon BE, Rosenman MB, Kleiman MB. Maternal and infant use of erythromycin and other macrolide antibiotics as risk factors for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J Pediatr. 2001;139:380–384. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.117577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooper WO, Griffin MR, Arbogast P, Hickson GB, Gautam S, Ray WA. Very early exposure to erythromycin and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:647–650. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.7.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 22.3 kb)

(DOCX 21 kb)

(PDF 1044 kb)

(DOC 132 kb)

(DOCX 21.1 kb)