Abstract

The pepper-bark tree (Warburgia salutaris) is one of the most highly valued medicinal plant species worldwide. Native to southern Africa, this species has been extensively harvested for the bark, which is widely used in traditional health practices. Illegal harvesting coupled with habitat degradation has contributed to fragmentation of populations and a severe decline in its distribution. Even though the species is included in the IUCN Red List as Endangered, genetic data that would help conservation efforts and future re-introductions are absent. We therefore developed new molecular markers to understand patterns of genetic diversity, structure, and gene flow of W. salutaris in one of its most important areas of occurrence (Mozambique). In this study, we have shown that, despite fragmentation and overexploitation, this species maintains a relatively high level of genetic diversity supporting the existence of random mating. Two genetic groups were found corresponding to the northern and southern locations. Our study suggests that, if local extinctions occurred in Mozambique, the pepper-bark tree persisted in sufficient numbers to retain a large proportion of genetic diversity. Management plans should concentrate on maintaining this high level of genetic variability through both in and ex-situ conservation actions.

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Plant sciences

Introduction

Medicinal plants have been used worldwide since ancient times, being particularly relevant in the developing world where ca. 80% of the population rely on these resources to fulfil their basic health care needs1–4. Additionally, at the global level the importance of bio-based compounds continues to grow and phytochemical research towards the identification of new active compounds of medical and nutritional importance is among top research priorities (e.g.5–14).

Sub-Saharan Africa harbours a vast repository of plant biodiversity, with 45,000 known vascular plant species15, many of which are used in traditional medicine16–20. However, efforts to safeguard this biodiversity are often compromised by anthropogenic pressures, with proximal drivers being land transformation, synergistic impacts of fires, grazing, climate change and harvesting (c.f.17,21–27), and growing commercialisation of medicinal plant in high demand (c.f.17,28,29). The last is motivated by preferences for certain species due to cultural identity, traditions, and lower costs in comparison with modern pharmaceuticals, even under circumstances of access to modern medical facilities21,30. On the other hand, the conservation status of many endemic and native species is poorly understood31,32 and many natural populations may be at risk. Current exploitation rates, often in tandem with other pressures like fire, invasive species, browsing and land transformation, threaten wild populations unless management methods are established, including community-based approaches17,21,30.

Under the current scenario of climate change and human population growth, the use of genomic tools is valuable to understand species evolution and adaptation in natural ecosystems33,34. The importance of phylogenetic data, genetic diversity, and population structure analyses to characterize the biodiversity of wild species has been well-established in numerous studies (e.g.35–39). Microsatellites (Single Sequence Repeats, SSR) are amongst the most efficient and widely used markers for these studies as they are codominant and highly polymorphic loci40. Although these markers are species specific, the increasing accessibility to next-generation sequencing41 has enabled the development of SSRs for the so-called orphan, neglected or wild crop relative species (e.g.42–45), although sequencing large plant genomes still remains a challenge46.

The pepper-bark tree, Warburgia salutaris (Bertol.) Chiov. (Family Canellaceae) is one of the most widely used and traded medicinal plants in southern Africa47. This slow growing species is part of an early diverging group of basal angiosperms, thought to be native to eastern and southern Africa48. However, subsequent studies confined the distribution of W. salutaris to only a sub-region of southern Africa, i.e. South Africa21,49, Eswatini (previously known as Swaziland)24,50, Zimbabwe29,51–53, Malawi54 and Mozambique55. This species is commonly used to treat several ailments such as common colds, throat and mouth sores, or coughs47,48.

In the past, sustainable harvesting of medicinal plants was regulated through traditional practises such as taboos, restrictions and harvesting tools30. However, with commercial demand increasing, W. salutaris groves were repeatedly raided by harvesters that often debarked the whole tree, especially mature plants56. Severe harvesting resulted in high tree mortality in many areas and in the extinction of many local populations21,24,57 and consequently, W. salutaris is considered threatened throughout its range50,58,59, and listed as an Endangered Species in the IUCN Red List57. The most extreme case is that of Zimbabwe, where the species is listed as extinct in the wild29,60. That resulted in the import of bark supplies in the late 1990s from Mozambique and South Africa53 being later trafficked from the same countries29. For instance, in South Africa, 43% of W. salutaris bark in the Johannesburg main market originated from Mozambique, with annual traded amounts estimated at 500–1000 kg28. As a result, populations of W. salutaris in Mozambique are currently restricted to fragmented patches in the Lebombo Mountains, Tembe River and Futi Corridor (Fig. 1)48. According to the Red List classification for Mozambique, this species is considered Vulnerable VU A2 cd58. Despite this critical situation, only a few studies on the populations dynamics of W. salutaris are available; of the 60 research and review papers available in the Web of Science on W. salutaris on 05 February 2020, only seven addressed this topic21,24,48,61–63 while the vast majority are focused on the medicinal applications of this species. Nevertheless, amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLPs) have been used to solve genetic relationships between W. ugandensis, W. salutaris and W. stuhlmanni showing a high degree of genetic variation among individuals within populations as well as between populations62.

Figure 1.

Location of the Lebombo Mountains, Tembe River, and Futi Corridor areas and their respective villages in southern Mozambique. Maps were generated with Idrisi Selva v.17.02 environment (Clark Labs, Clark University, www.clarklabs.org).

In this work, we have developed SSRs markers for W. salutaris to investigate the genetic legacy of exploitation in this slow growing species and to contribute to future re-introduction actions. For that, we have used its best known area of occurrence, Mozambique (Fig. 1) to addressed the following questions: (1) How is genetic diversity distributed within and among individuals across geographical areas?; (2) Is the genetic structure associated with the geographical distribution?; and (3) Is there any evidence of inbreeding or lack of gene flow between populations?

Results

Genetic diversity

For each locus, the numbers of alleles varied from three (13-N1132836, 16-N1150626 and 18-N1173706 locus) to nine (31-N2284857 and 43-N1009973 locus) with an average of 5.8 ± 2.3 alleles per locus and a total of 58 alleles considering all loci (Table 1). The average observed and expected heterozygosis per loci varied from 0.299 ± 0.186 (16-N1150626) to 0.852 ± 0.062 (10-N1110523), and from 0.249 ± 0.109 (16-N1150626) to 0.812 ± 0.048 (31-N2284857), respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics and genetic diversity statistics of the 10 polymorphic microsatellite markers developed for Warburgia salutaris.

| Locus | Repeat motif | Accession number | Primer Sequence 5′–3′ | Size range | Na | Ho | He |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-N1002135 | (ATG)5 | MT515706 |

F: TATGTTGGGAGAGGGTGAGG R: GTTTAACGACTGCATCATCCCA |

132–174 | 6 | 0.487 ± 0.139 | 0.394 ± 0.101 |

| 7-N1082598 | (AAT)9 | MT515707 |

F: GTTGATCATAGACACGCCAAGG R: GTCGTGCAACCTAGAGGTCC |

161–182 | 7 | 0.633 ± 0.085 | 0.700 ± 0.029 |

| 10-N1110523 | (TTA)9 | MT515708 |

F: AACCATTGGCACCTCAAGTC R: GTTGAAGTTGAGGGAAGGGATG |

244–262 | 7 | 0.852 ± 0.060 | 0.786 ± 0.023 |

| 12-N1126672 | (TTG)7 | MT515709 |

F: GTTAAATCTGGACCCACTTGCC R: GGGTGAATTAGTGAACGTCTTG |

161–180 | 7 | 0.805 ± 0.125 | 0.718 ± 0.074 |

| 13-N1132836 | (AAG)7 | MT515710 |

F: GTTCCTGCTCCGAGACCTAGAA R: TCATGAAGAAATCGCAACCA |

138–144 | 3 | 0.304 ± 0.087 | 0.296 ± 0.086 |

| 16-N1150626 | (TGG)5 | MT515711 |

F. GTCTTTGGCGAAATCAGTTGGT R: GAAGGTTTCCAGGTTGGTGA |

149–159 | 3 | 0.299 ± 0.186 | 0.249 ± 0.109 |

| 18-N1173706 | (AAG)6 | MT515712 |

F: GAGCTGCCTCGATATGGACT R: GTTATCCAATGGCCAAGAAACC |

164–170 | 3 | 0.398 ± 0.105 | 0.421 ± 0.078 |

| 31-N2284857 | (TTC)12 | MT515713 |

F: GTCTCTTGCTATCATGCGGTCA R: CAGATTGGAGAATCCAGACCA |

207–263 | 9 | 0.771 ± 0.138 | 0.812 ± 0.078 |

| 33-N3477883 | (TGA)6 | MT515714 |

F: GTACAAGATTCATGTGACCGGC R: GCAAGGCATCATATTCACGA |

184–200 | 4 | 0.550 ± 0.171 | 0.472 ± 0.124 |

| 43-N1009973 | (AT)10 | MT515715 |

F: GTTGCGCTCATCGATCTGTA R: GTGCGAACTATGATCGGACGAA |

146–185 | 9 | 0.439 ± 0.102 | 0.778 ± 0.027 |

For each loci, the repeat motif, Genbank accession number, primer sequence, and size range (bp) is indicated. Na refers to the number of alleles, Ho to observed heterozygosity (mean ± SE) and He to expected heterozygosity (mean ± SE).

From the three sampling areas of W. salutaris 156 alleles were found in the 48 individuals sampled, being the number of alleles higher in LM than in the other two areas (Table 2). The average Shannon’s diversity index (I) was also higher in LM than in TR and FC. Observed and expected heterozygosis had similar average values in LM and TR being slightly lower in FC. The polymorphic information content (PIC) had high average values while inbreeding coefficients (FIS) were low and showing negative values in the three sampling areas.

Table 2.

Genetic diversity of Warburgia salutaris in the three study areas.

| Locus | Lebombo Mountains (LM) | Tembe River (TR) | Futi Corridor (FC) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | I | Ho | He | PIC | Na | I | Ho | He | PIC | Na | I | Ho | He | PIC | |

| 1-N1002135 | 3 | 0.809 | 0.579 | 0.499 | 0.499 | 3 | 0.840 | 0.667 | 0.491 | 0.491 | 2 | 0.340 | 0.214 | 0.191 | 0.191 |

| 7-N1082598 | 7 | 1.457 | 0.526 | 0.672 | 0.672 | 9 | 1.764 | 0.800 | 0.758 | 0.758 | 8 | 1.516 | 0.571 | 0.671 | 0.671 |

| 10-N1110523 | 9 | 1.942 | 0.895 | 0.832 | 0.832 | 5 | 1.480 | 0.733 | 0.762 | 0.762 | 7 | 1.649 | 0.929 | 0.763 | 0.763 |

| 12-N1126672 | 7 | 1.716 | 0.842 | 0.795 | 0.795 | 7 | 1.739 | 1.000 | 0.789 | 0.789 | 4 | 1.061 | 0.571 | 0.569 | 0.569 |

| 13-N1132836 | 2 | 0.576 | 0.421 | 0.388 | 0.388 | 2 | 0.245 | 0.133 | 0.124 | 0.124 | 2 | 0.562 | 0.357 | 0.375 | 0.375 |

| 16-N1150626 | 3 | 0.455 | 0.158 | 0.234 | 0.234 | 2 | 0.637 | 0.667 | 0.444 | 0.444 | 2 | 0.154 | 0.071 | 0.069 | 0.069 |

| 18-N1173706 | 3 | 0.942 | 0.579 | 0.564 | 0.564 | 3 | 0.680 | 0.400 | 0.407 | 0.407 | 2 | 0.469 | 0.214 | 0.293 | 0.293 |

| 31-N2284857 | 14 | 2.429 | 0.947 | 0.895 | 0.895 | 9 | 1.884 | 0.867 | 0.816 | 0.816 | 6 | 1.487 | 0.500 | 0.727 | 0.727 |

| 33-N3477883 | 4 | 0.954 | 0.526 | 0.517 | 0.517 | 3 | 0.468 | 0.267 | 0.238 | 0.238 | 3 | 1.090 | 0.857 | 0.661 | 0.661 |

| 43-N1009973 | 11 | 1.980 | 0.632 | 0.801 | 0.810 | 9 | 1.827 | 0.400 | 0.798 | 0.798 | 5 | 1.438 | 0.286 | 0.724 | 0.724 |

| Average ± SE | 6.300 ± 1.274 | 1.326 ± 0.213 | 0.611 ± 0.075 | 0.620 ± 0.068 | 0.621 ± 0.216 | 5.200 ± 0.952 | 1.156 ± 0.203 | 0.593 ± 0.089 | 0.563 ± 0.081 | 0.563 ± 0.256 | 4.100 ± 0.722 | 0.977 ± 0.175 | 0.457 ± 0.089 | 0.504 ± 0.080 | 0.504 ± 0.252 |

Na refers to the number of alleles, I to Shannonʼs diversity index, Ho to observed heterozygosity (mean ± SE), He to expected heterozygosity (mean ± SE) and PIC to polymorphic information content.

Population genetic structure and differentiation

The Bayesian clustering program STRUCTURE found the highest LnP(D) and ΔK values for K = 2 (Fig. 2; Fig. S1). One cluster was predominantly found across LM and TR areas, while a second one characterized the FC area. Nevertheless, some individuals in this last area showed signs of genetic admixture between the two genetic groups (* indicated in Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Population structure of Warburgia salutaris based on 10 SSRs and using the best assignment result retrieved by STRUCTURE (K = 2). Each individual sample is represented by a thin vertical line divided into K coloured segments that represent the individual’s estimated membership fractions in K clusters. Populations and main geographical areas are indicated below following Table 4. Asterisks indicate individuals with a probably of membership lower than 90% to the main genetic cluster, as revealed by STRUCTURE.

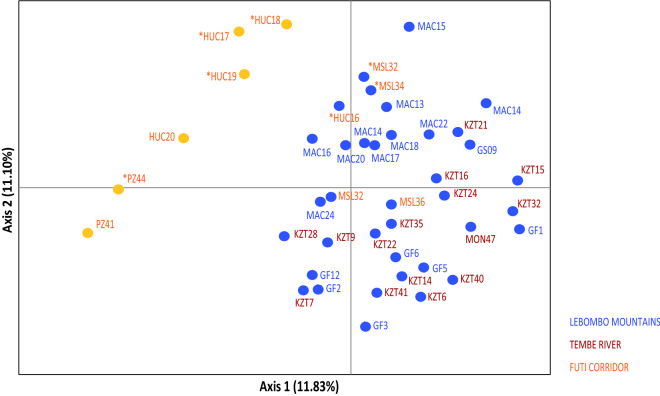

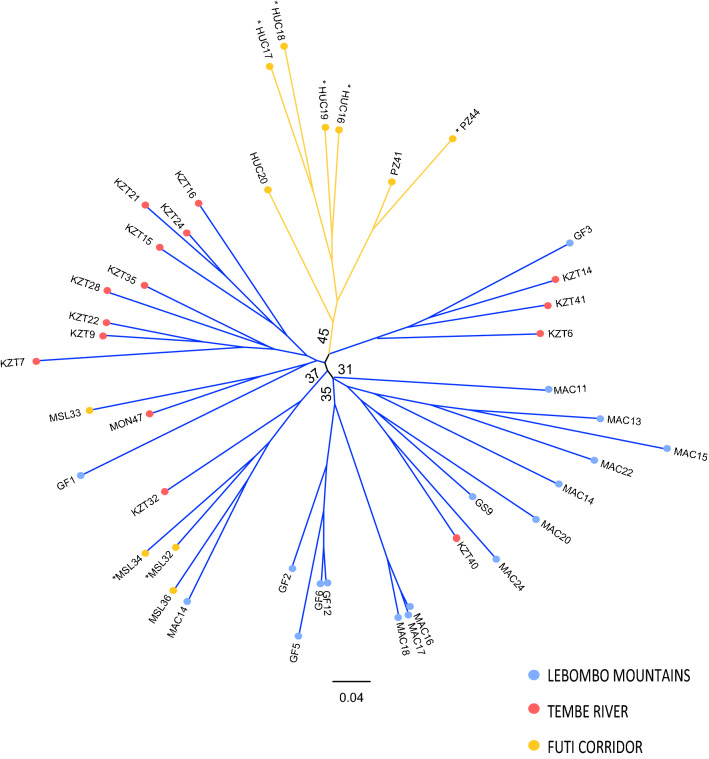

The first two coordinates of the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) explained 22.9% of the total variation, and populations were spatially separated into the two main groups found by STRUCTURE (Fig. 3). The neighbour-joining tree revealed several small clusters although mostly with a very low support (< 30% BS) and overall, with no association between the clusters found and the three geographic areas (Fig. 4) as reported in the other analyses. However, a clear cluster grouped all the FC geographical area.

Figure 3.

Principal Coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the studied Warburgia salutaris using the scored SSRs markers. Percentage of explained variance of each axis is given in parentheses. Population labels follow Table 4. Colour of symbols (circles) indicate the two genetic groups identified by STRUCTURE. Colour of labels follow the three main geographic areas as depicted in Fig. 1. Asterisks as in Fig. 2.

Figure 4.

Unrooted neighbour-joining tree of the studied Warburgia salutaris based on Nei’s Da genetic distance. Numbers associated with branches indicate bootstrap values (BS) based on 1000 replications. Only BS above 30 are shown. Colours of branches indicate the two genetic groups identified by STRUCTURE. Colour of circles near each label indicate the three main geographic areas as depicted in Fig. 1. Asterisks as in Fig. 2.

The pairwise population FST values varied from 0.049 (TR vs. LM) to 0.114 (FC vs. TR) revealing moderate levels of genetic differentiation between FC and TR and between FC and LM and lower levels between TR and LM (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pairwise population FST values for Warburgia salutaris in the three study areas.

| Population | Lebombo Mountains | Tembe River | Futi Corridor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lebombo Mountains | 0.000 | ||

| Tembe River | 0.049 | 0.000 | |

| Futi Corridor | 0.084 | 0.114 | 0.000 |

Discussion

High genetic diversity and admixture in Warburgia salutaris

Assessment of genetic diversity is critical to understand the ability of a species to cope with changing conditions and environments, especially for threatened species39,64–68. In this study, we reported for the first time the development of Single Sequence Repeats (SSR) markers in W. salutaris by employing next generation sequencing (Illumina platform). The 10 SSRs markers were validated and found to be highly polymorphic, with values similar to the ones found in other threatened species such as Acer miaotaiense (PIC = 0.604)69 or Corylus avellana (PIC = 0.778)70. These markers are now available to extend W. salutaris population studies to a worldwide level. Additionally, the SSRs developed during this work might potentially be suitable to study genetic diversity in other species within the genus Warburgia, since only a limited number of studies is available and based on Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP)62,71, a time-consuming and costly technique. To the best of our knowledge, the present study represents the first genome size estimation of W. salutaris and only the second within the Canellaceae family having a genome size 4 × smaller than Canella winterana (2C = 11.7 pg72,73). The relatively small genome size of W. salutaris (see methods) is within the range of the non-expanded genomes of currently known magnoliids (Fig. S2) and may facilitate future genomic initiatives although further analyses are needed to determine its ploidy level.

Due to the heavy harvesting pressure to which W. salutaris is subjected in Mozambique28,48, genetic diversity levels were expected to be low. However, we found high levels of genetic diversity in the three surveyed areas in comparison to other narrowly distributed species, as for instance, the tropical tree Paypayrola blanchetiana (Na: 2–5 alleles per locus; Ho: 0.063–0.563 in the two populations; He: 0.063–0.567 in the first population and 0.063–0.627 in the second)39. However, genetic diversity indices of W. salutaris were similar to other species where bark has been heavily-exploited, such as Cinchona officinalis (Na: 5.2–7.6 alleles per locus; Ho: 0.580–0.680; He: 0.616–0.717)74 or even lower than Himatanthus drasticus (Na: 6–24; Ho: 0–0.847, He: 0–0.864)34.

High levels of heterozygosis may be due to factors including the reproductive system such as self-incompatibility75 or high gene flow65,76. Results from this work revealed a range of the inbreeding coefficient of -0.492 (TR) to -0.363 (LM), which is much lower than those found in e.g. H. drasticus (0.248–0.303)34, Calotropis gigantea (0.167), C. procera (0.177)77, or Phoenix theophrasti (0.9)78. The negative inbreeding values found here suggest the existence of random mating79 among individuals of W. salutaris and might also explain the levels of heterozygosis found here. Indeed, the related species Warburgia ugandensis has a mixed mating system being predominantly outcrossing62. Additionally, insect pollinators of W. salutaris such as bees are probably able to travel over the large agricultural blocks separating the three geographical areas studied here, promoting gene flow. Genetic admixture between sites might also be facilitated by frugivorous birds that often eat the berries thereby facilitating the dispersion of seeds. In accordance, we found high levels of genetic admixture between populations with only two genetic clusters being found, one grouping the northern populations and the other one, the southern populations.

Our study suggests that, although some local populations might have been severely affected by harvesting, the pepper-bark tree might have persisted in sufficient numbers in Mozambique to allow outcrossing between sites, retaining a large proportion of genetic diversity. Although there are no records of the historical distribution of this species, the studied populations could be relicts of once much larger populations that persisted in specific locations. In addition, recent conservation efforts might have diminished trade in Mozambique, avoiding severe barking in these populations. Further research should focus on understanding the factors limiting the regeneration of W. salutaris trees.

Population differentiation between geographic areas

Population differentiation of endangered species is variable. For example, low differentiation was found between populations of Platanthera leucophaea (FST < 0.02 over distances < 2 km80) while in H. drasticus the differentiation levels were high (FST from 0.036 to 0.077 over short distances)34. In contrast, the endangered Paeoma rockii revealed a high differentiation between populations (FST varied from 0.780 to 0.982)81. Despite the narrow distributional area of W. salutaris in Mozambique, this study revealed a high genetic differentiation between the northern populations located in LM and TR and the southern populations located in FC (Fig. 1). Pairwise FST comparisons showed lower genetic differentiation between LM and TR (0.049), which are separated by only 28 km, than either between LM and FC areas (0.084, separated by 81 km) or between TR and FC (0.114, separated by 49 km). STRUCTURE analyses also found a distinct genetic cluster in the FC area, which was also supported by PCoA analyses and the NJ tree. Contrary to LM and TR areas, where W. salutaris occurs in slopes and forest patches, in the FC area this species occurs near seasonal pans in thicket vegetation associated with termitaria on clay soils82,83. This might imply differences in reproductive ecology, particularly regarding flowering phenology and the activity of pollinators, which would affect gene flow with the other sites, explaining the genetic structure and population differentiation found between the studied sites. Thus, the differentiated FC genetic clusters could be harbouring novel and important alleles and should be given priority in in situ and ex situ conservation strategies in Mozambique77,84,85.

How to conserve a species widely exploited and needed?

Several populations of W. salutaris are threatened by fire from slash and burn agriculture, as they occur in adjacent patches or in agricultural lands48. Equally, burning of natural vegetation to improve livestock fodder, poaching, and opening of new areas for settlements are also potential threats to the species (e.g.86–88). Vegetative propagation of W. salutaris is possible through tissue culture63 although expensive. This species is being largely cultivated ex situ in South Africa89 and in small scale in Zimbabwe53 and Mozambique (unpublished data), to encourage the sustainable use of the species. Home gardening would also be important for this species although that requires the involvement of local communities and understanding their perceptions towards the conservation of this species.

Considering the confined distribution and threatened status, the long-term persistence of W. salutaris should be secured by conserving the maximum genetic diversity of the species. As it is impossible to designate every natural wild plant habitat as a protected area, nurseries could be implemented to ensure production stability. The disclosure of genetic variation and understanding of genetic relatedness within populations is useful for their sustainable uses90. Knowledge of genetic diversity from other countries as the one reported here would also help to implement conservation strategies including re-introduction programs, selecting the most suitable material to be used. Understanding the degree of genetic variation between Mozambique and the neighbouring countries would facilitate transborder conservation actions. Further studies must also be conducted to detect and understand how reductions of natural regeneration or fitness are affected by harvesting. Finally, efforts to educate the local population and landowners on the importance of conserving the natural populations of W. salutaris should continue.

Methods

Study species

Warburgia salutaris is an evergreen tree, generally 5–10 m tall, but occasionally up to 20 m57. The flowers are small (< 7 mm in diameter), white to greenish in colour, generally solitary or in tight, few-flowered heads, borne on short, robust stalks in the axils of the leaves from autumn to winter (April–June). Flowers are bisexual, actinomorphic (having symmetrically arranged perianth parts of similar size or shape that are divisible into 3 or more equal halves). Flowers are visited by many insect species, most especially bees. The flowers develop rounded, oval berries (30 mm in diameter), usually dark-green and turning purple during ripening that occurs throughout winter an into early summer (July to December). Dispersion occurs by frugivorous birds that disperse the seeds, although fruits can also drop near the maternal tree. Leaves are glossy and dark green, with a bitter, peppery taste. The stem is covered by a brown bark marked with corky lenticels and is bitter and peppery and is widely used medicinally. The active compounds (drimanes and sesquiterpenoides) are mostly found in the inner part of the stem and root bark.

Study area

The present study was carried out in the districts of Matutuine and Namaacha (Mozambique), in the three areas of known occurrence of W. salutaris48: (1) Lebombo Mountains (LM) also named the western area, (2) Tembe River (TR) or centre, and (3) Futi Corridor (FC) or eastern area (Fig. 1). The climate is subtropical to tropical, encompassing a wet (October–April) and dry season (May–September). The mean annual temperature ranges from 21 to over 24 °C, and the mean annual rainfall from 600 to 1000 mm88,91. In LM, W. salutaris is accompanied by Acacia nigrescens Oliv., Acacia burkei Benth. and Combretum apiculatum Sond, although Aloe marlothii A. Berger, Ficus spp. and Euphorbia spp. are found in shallow soils, and Olea africana Miller and Combretum spp. in steeper stony slopes92,93. In TR, W. salutaris is found in sand forest patches together with Pteleopsis myrtifolia (M.A.Lawson) Engl. & Diels, Cleistanthus schlechteri Pax (Hutch.), Hymenocardia ulmoides Oliv. and Monodora junodii Engl. & Diels94. The open savanna woodland links the patches of W. salutaris, being composed mainly by Strychnos spp., Terminalia sericea Burch. ex DC., Acacia burkei Benth., Combretum molle R. Br. ex G.Don and Albizia versicolor Oliv.95. In FC, W. salutaris occurs near seasonal pans96 in thicket vegetation associated to termitaria in clay soils82. Common tree species found in this community include Berchemia zeyheri (Sond.) Grubov, Pappea capensis Eckl. & Zeyh. and Olea europaea subsp. africana (Miller) P.S. Green97. The primary economic activities of local residents are subsistence agriculture, livestock rearing, trade of non-timber forest products and migrant labour to South Africa87,98,99.

Population sampling, DNA extraction, genome size value, and SSR development

Based on the areas of occurrence (Senkoro et al., unpublished data), 48 individuals were sampled: 19 individuals from LM, 15 from TR and 14 from LM (Table 4). Fresh, young undamaged leaves were collected for each individual plant and frozen at − 80 °C until DNA isolation. Total genomic DNA was extracted from 50 mg of ground leaves using the InnuSPEED Plant DNA Kit (Analytik Jena Innuscreen GmbH, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The average yield and purity were assessed spectrophotometrically by OD230, OD260 and OD280 readings (Nanodrop 2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and visualized by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels under UV light. Normalized DNA from five individuals of each population was used to develop the SSR markers at CD Genomics (cd-genomics.com/hi-ssrseq.html).

Table 4.

Sampled accessions and locations of Warburgia salutaris sorted by geographical area.

| Accessions | Location | ID | Lat | Long | Accessions | Location | ID | Lat | Long |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GF1 (1) | Goba Fronteira | LM | − 26.23266 | 32.09810 | KZT16 (27) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.40994 | 32.35490 |

| MAC13 (2) | Macanda | LM | − 26.03522 | 32.12181 | KZT21 (28) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.40391 | 32.36711 |

| MAC14 (3) | Macanda | LM | − 26.03577 | 32.12150 | KZT22 (29) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.40059 | 32.35109 |

| MAC15 (4) | Macanda | LM | − 26.03778 | 32.12730 | KZT24 (30) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.40206 | 32.36188 |

| MAC16 (5) | Macanda | LM | − 26.03692 | 32.12772 | KZT28 (31) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.36735 | 32.37323 |

| MAC17 (6) | Macanda | LM | − 26.05158 | 32.11803 | KZT35 (32) | Kazimat | TR | 26.36737 | 32.37266 |

| MAC18 (7) | Macanda | LM | − 26.05159 | 32.11565 | KZT40 (33) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.36873 | 32.37078 |

| MAC19 (8) | Macanda | LM | − 26.81118 | 32.64545 | KZT41 (34) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.36929 | 32.37334 |

| MAC20 (9) | Macanda | LM | − 26.04696 | 32.11979 | KZT46 (35) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.36935 | 32.37321 |

| MAC22 (10) | Macanda | LM | − 26.04508 | 32.11982 | MON47 (36) | Monucua | TR | − 26.36952 | 32.32288 |

| MAC24 (11) | Macanda | LM | − 26.03521 | 32.12181 | Huc16 (44) | Huco | FC | − 26.85013 | 32.60338 |

| GF2 (12) | Goba Fronteira | LM | − 26.26867 | 32.10719 | Huc17 (45) | Huco | FC | − 26.86159 | 32.60604 |

| GF5 (13) | Goba Fronteira | LM | − 26.23250 | 32.09818 | Huc18 (46) | Huco | FC | − 26.86169 | 32.60353 |

| GF6 (14) | Goba Fronteira | LM | − 26.23241 | 32.09815 | Huc19 (47) | Huco | FC | − 26.86129 | 32.60282 |

| GF12 (15) | Goba Fronteira | LM | − 26.23240 | 32.09822 | Huc20 (48) | Huco | FC | − 26.86025 | 32.60309 |

| GS09 (16) | Goba Sede | LM | − 26.23238 | 32.09822 | MSL32 (49) | Massale | FC | − 26.83979 | 32.88339 |

| MAC11 (17) | Macanda | LM | − 26.04509 | 32.11983 | MSL33 (50) | Massale | FC | − 26.86458 | 32.60790 |

| GF3 (18) | Goba Fronteira | LM | − 26.26879 | 32.10747 | MSL34 (51) | Massale | FC | − 26.80948 | 32.64368 |

| GF4 (19) | Goba Fronteira | LM | − 26.23233 | 32.09818 | MSL36 (52) | Massale | FC | − 26.80590 | 32.63823 |

| KZT6 (22) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.41303 | 32.36338 | Pz41 (53) | Phuza | FC | − 26.78824 | 32.67368 |

| KZT7 (23) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.41190 | 32.36422 | Pz42 (54) | Phuza | FC | − 26.78817 | 32.67434 |

| KZT9 (24) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.40960 | 32.36578 | Pz43 (55) | Phuza | FC | − 26.78814 | 32.67383 |

| KZT14 (25) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.40414 | 32.35073 | Pz44 (56) | Phuza | FC | − 26.78760 | 32.67419 |

| KZT15 (26) | Kazimat | TR | − 26.38806 | 32.35008 | Pz45 (57) | Phuza | FC | − 26.81144 | 32.66415 |

LM Lebombo Mountains, TR Tembe River, FC Futi Corridor.

For the development of the markers, we first estimated the nuclear DNA content of W. salutaris by flow cytometry using fresh young leaves that were chopped using a razor blade together with an internal standard in a Petri dish containing 1 mL of Woody Plant Buffer100 following the protocol described in101. Solanum lycopersicum ‘Stupické’ (2C = 1.96 pg)102 was used as internal standard. The nuclear suspension was then filtered through a 30 μm nylon filter, and 50 μg/mL of propidium iodide (PI; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and 50 μg/mL of RNase (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to stain the DNA only. The fluorescence intensity of nuclei was analysed using a CyFlow Space flow cytometer (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan). Four independent replicates collected from Kazimat (TR) were measured. Conversion of mass values into numbers of base pairs was done according to the factor 1 pg = 978 Mbp103. The mean 2C-value of W. salutaris was found to be 2.91 pg (± 0.068), corresponding to an average genome size of 2845 Mbp (Fig. S2). Samples had an average coefficient of variation of 4.18%.

Genomic libraries were constructed using the KAPAHyper prep kit and sequenced by Illumina Hiseq 2500. We firstly used SSRHunter1.3 to screen the potential SSRs from the sequenced data that had at least five repeats (penta-) for 3–5 bp units. Based on the obtained sequences, primers were designed with Primer Premier 5.0 software (Table 1). Fourteen geographically representative samples of W. salutaris (LM, TR and FC; Fig. 1) were first used to test microsatellite amplification and to troubleshoot amplification conditions. Amplifications were performed in 15 μl reactions containing: 1.25U TaKaRa Hot startTaq polymerase, 1X Buffer I, 1 mM dNTPs, 5 μM Primer F and R and 100 ng DNA. The PCR amplification conditions were run as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, 94 °C for 30 s, 30 cycles of 56 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, 94 °C for 30 s, 10 cycles of 53 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s and final extension at 60 °C for 30 min. We then considered 10 markers that presented > 20% polymorphism, which were used to amplify all samples within this study (Table 1). The amplified fragments were analysed on a 3730 × 1 gene analyzer (Thermo Fischer Scientific) and examined manually for microsatellite peaks. Allele sizes were determined using GeneMapper 3.2 (Applied Biosystems).

Estimates of genetic diversity

For each microsatellite locus, genetic polymorphism was assessed in 48 individuals by calculating the number of alleles (Na), observed heterozygosis (Ho), expected heterozygosis (He), Shannon’s diversity index (I), and inbreeding coefficient (FIS) using GenALEX software version 6.5104. The polymorphic information content (PIC) was calculated as PIC = 1 − ΣPi2, where Pi is the allele frequency for each SSR marker locus105,106. Values of PIC above 0.5 were considered highly informative, between 0.5 and 0.25 moderately informative, and below 0.25 less informative107.

Population genetic structure and differentiation

The Bayesian program STRUCTURE v.2.3.4108 was used to infer the population structure and to assign individual plants to subpopulations. Models with a putative numbers of populations (K) from 1–5, imposing ancestral admixture and correlated allele frequencies priors, were considered. Ten independent runs with 50 000 burn-in steps, followed by run lengths of 1 000 000 interactions for each K, were computed. The number of clusters in the data was estimated using STRUCTURE HARVESTER109, which identifies the optimal K based both on the posterior probability of the data for a given K and the ΔK110. To correctly assess the membership proportions (q values) for clusters identified in STRUCTURE, the results of the replicates at the best fit K were post-processed using CLUMPP 1.1.2111. GenALEX software version 6.5104 was used to calculate the Nei’s genetic distance112 among individuals. A Principle Coordinate Analysis (PCoA)113 was performed to detect genetic variations between W. salutaris individuals. POPULATION 1.2114 was used to construct an unrooted neighbour-joining tree with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The Wright’s FST value was computed to estimate population differentiation104. Lower genetic differentiation was considered for FST below 0.05, moderate from 0.05 to 0.15 and high genetic differentiation above 0.25115.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), Russell E. Train Education for Nature Program, World Wildlife Fund (Agreement #SS20), Camões, I.P. (Portugal), and the Portuguese Science and Technology Foundation through the research units UIDB/00239/2020 (CEF) and UID/04129/2020 (LEAF), and the contribution to the International Rice Research Institute. We would also like to thank our field guides Antonio Tembe, Ernesto Bié, Filimone Cossa, Luis Cossa, Massale Tembe, Ricardo Mundlovu and Sifiso Masuko for their support during sample collection. We are also grateful to our colleagues, Domingos Maguengue, Ivete Maquia, and Ana Gomes during the initial phase of the work and to José Alfredo Amanze for providing the study area map.

Author contributions

A.M.S., C.M.S., R.A.V., and A.I.R.B. conceived the work and the experimental design. A.M.S., C.M.S., and R.A.V. performed the field data survey and sample collection. A.M.S., P.B.S., F.S., and P.T. performed the laboratorial analysis. P.T. performe the flow cytometry data analysis. A.M.S., F.S., I.M. and A.I.R.B. performed the microsatellite data analysis. A.M.S., I.M., and A.I.R.B. wrote the first draft and final version of the manuscript, which has been thoroughly reviewed by all authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Isabel Marques, Email: isabelmarques@isa.ulisboa.pt.

Ana I. Ribeiro-Barros, Email: aribeiro@isa.ulisboa.pt

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-76654-6.

References

- 1.Mukherjee PW. Quality Control of Herbal Drugs: An Approach to Evaluation of Botanicals. New York: Business Horizons Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodeker C, et al. WHO Global Atlas of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandaranayake WM. Quality control, screening, toxicity, and regulation of herbal drugs. In: Ahmad I, Aqil F, Owais M, editors. Modern Phytomedicine, Turning Medicinal Plants into Drugs. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2006. pp. 25–57. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO). Traditional and Complementary Medicine Policy. Management Science for Health. https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19582en/s19582en.pdf (2012). Accessed 13 May 2020.

- 5.Mulaudzi RB, Ndhlala AR, Kulkarni MG, Finnie JF, van Staden J. Antimicrobial properties and phenolic contents of medicinal plants used by the Venda people for conditions related to venereal diseases. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wangchuck P, Keller PA, Pyne SG, Willis AC, Kamchonwongpaisan S. Antimalarial alkaloids from Bhutanese traditional medicine plant Corydalis dubia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012;143:310–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangal M, Sagar P, Singh H, Raghava GPS, Agarwal SM. NPACT: naturally occurring plant-based anti-cancer compound-activity-target database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1124–D1129. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munodawafa T, Chagonda LS, Moyo SR. Antimicrobial and phytochemical screening of some Zimbabwean medicinal plants. J. Biol. Active Prod. Nat. 2013;3:323–330. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gechev TS, et al. Natural products from resurrection plants: potential for medical applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014;32:1091–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lalisan JA, Nuñeza OM, Uy MM. Brine Shrimp (Artemia salina) bioassay of the medicinal plant Pseudelephantopus spicatus from Iligan City, Philippines. Int. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 2014;3:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du K, et al. Labdane and clerodane diterpenoids from Colophospermum mopane. J. Nat. Prod. 2015;78:2494–2504. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moyo B, Mukanganyama S. Antiproliferative activity of T. welwitschii extract on Jurkat T cells in vitro. BioMed Res. Int. 2015;2015:817624. doi: 10.1155/2015/817624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Idris OA, Wintola OA, Afolayan AJ. Phytochemical and antioxidant activities of Rumex crispus L. in treatment of gastrointestinal helminths in eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2017;7:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iqbal J, et al. Plant-derived anticancer agents: a green anticancer approach. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2017;7:1129–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linder HP. The evolution of plant diversity. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2014;2:38. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2014.00038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ribeiro A, Romeiras MM, Tavares J, Faria MT. Ethnobotanical survey in Canhane village, district of Massingir, Mozambique: medicinal plants and traditional knowledge. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moyo M, Adeyemi O, Aremu AO, van Staden J. Medicinal plants: an invaluable, dwindling resource in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;174:595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moura I, Maquia I, Rija AA, Ribeiro N, Ribeiro-Barros AI. Biodiversity studies in key species from the African Mopane and Miombo woodlands. In: Bitz L, editor. Genetic Diversitycxs. Rijeka: Intech; 2017. pp. 92–109. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alaribe FN, Motaung KSCM. Medicinal plants in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine in the African continent. Tissue Eng. 2019;A25:827–829. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2019.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burlando B, Palmero S, Cornara L. Nutritional and medicinal properties of underexploited legume trees from West Africa. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019;59:S178–S188. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1551776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Botha J, Witkowski ETF, Shackleton CM. The impact of commercial harvesting on Warburgia salutaris (‘pepper-bark tree’) in Mpumalanga, South Africa. Biodivers. Conserv. 2004;13:1675–1698. doi: 10.1023/B:BIOC.0000029333.72945.b0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouki J, Arnold K, Martikainen P. Long-term persistence of aspen—a key host for many threatened species—is endangered in old growth conservation areas in Finland. J. Nat. Conserv. 2004;12:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2003.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giam X, Bradshaw CAJ, Tan HTW, Sodhi NS. Future habitat loss and the conservation of plant biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2010;143:1594–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dludlu MN, Dlamini PS, Sibandze GS, Vilane VS, Dlamini CS. The distribution and conservation status of the endangered pepperbark tree Warburgia salutaris (Canallaceae) in Swaziland. Oryx. 2017;51:441–454. doi: 10.1017/S0030605316000302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng G, Mao L, Benito BM, Swenson NG, Svenning J-C. Historical anthropogenic footprints in the distribution of threatened plants in China. Biol. Conserv. 2017;210:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pramanik M, Paudel U, Mondal B, Chakraborti S, Deb P. Predicting climate change impacts on the distribution of the threatened Garcinia indica in the Western Ghats, India. Clim. Risk Manag. 2018;19:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2017.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudley A, Butt N, Auld TD, Gallagher RV. Using traits to assess threatened plant species response to climate change. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019;28:1905–1919. doi: 10.1007/s10531-019-01769-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krog, M., Falcão, M. & Olsen, C. S. Medicinal plant markets and trade in Maputo, Mozambique (Danish Center for Forest, Landscape and Planning, KVL, 2006).

- 29.Mukamuri BB, Kozanayi W. Commercialization and institutional arrangements involving tree species harvested for bark by smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. In: Cunningham AB, Campbell BM, Luckert MK, editors. Bark Use, Management and Commerce in Africa. New York: The New York Botanical Garden Press; 2014. pp. 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunningham, A. B. African Medicinal Plants: Setting Priorities at the Interface Between Conservation and Primary Health Care (UNESCO, 1993).

- 31.Maquia I, et al. Diversification of African tree legumes in Miombo-Mopane woodlands. Plants. 2019;6:182. doi: 10.3390/plants8060182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribeiro-Barros AI, Catarino S, Moura I, Ramalho JC, Romeiras MM, Ghodhbane-Gtari F. Actinorhizal trees and shrubs from Africa: distribution, conservation and uses. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2019;112:31–46. doi: 10.1007/s10482-018-1174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scribner KT, Meffe GF, Groom MJ. Conservation genetics: the use and importance of genetic information. In: Groom MJ, Meffe GK, Carroll CR, editors. Principles of Conservation Biology. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers; 2006. pp. 375–415. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baldauf C, Ciampi-Guillardi M, dos Santos FAM, de Souza AP, Sebbenn AM. Tapping latex and alleles? The impacts of latex and bark harvesting on the genetic diversity of Himatanthus drasticus (Apocynaceae) For. Ecol. Manag. 2013;310:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2013.08.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Sousa VA, et al. Genetic diversity and biogeographic determinants of population structure in Araucaria angustifolia (Bert.) O. Ktze. Conserv. Genet. 2020;21:217–229. doi: 10.1007/s10592-019-01242-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu J, et al. Comparative analysis of genetic diversity in sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.) using AFLP and SSR markers. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012;39:3637–3647. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1138-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maquia I, et al. Genetic diversity of Brachystegia boehmii Taub. and Burkea africana Hook. f. across a fire gradient in Niassa National Reserve, northern Mozambique. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2013;48:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2012.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bessega C, Cony M, Saidman BO, Aguilo A, Vilardi JC. Genetic diversity and differentiation among provenances of Prosopis flexuosa DC (Leguminosae) in progeny trial: implication for arid land restoration. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019;44:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2019.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braun M, Esposito T, Huette B, Harand AP. Development and characterization of eleven microsatellite loci for the tropical understory tree Paypayrola blanchetiana Tul. (Violaceae) Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019;46:529–2532. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-04622-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zane L, Bargelloni L, Patarnello T. Strategies for microsatellite isolation: a review. Mol. Ecol. 2002;11:1–16. doi: 10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackson SA, Iwata A, Lee S-H, Schmutz J, Shoemaker R. Sequencing crop genome: approaches and applications. New Pathol. 2011;191:915–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Camacho LMD, et al. Development, characterization and cross-amplification of microsatellite markers for Chrysolaena obovata, an important Asteraceae from Brazilian Cerrado. J. Genet. 2017;96:47–53. doi: 10.1007/s12041-017-0812-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dantas LG, Alencar L, Huettel B, Pedrosa Harandet A. Development of ten microsatellite markers for Alibertia edulis (Rubiaceae), a Brazilian savanna tree species. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019;46:4593. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-04819-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eom SH, Na J-K. Leaf transcriptome data of two tropical medicinal plants: Sterculia lanceolata and Clausena excavate. Data Brief. 2019;25:104297. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2019.104297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mercati F, et al. Transcriptome analysis and codominant markers development in caper, a drought tolerant orphan crop with medicinal value. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:10411. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46613-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kyriakidou M, Tai HH, Anglin NL, Ellis D, Strömvik MV. Current strategies of polyploid plant genome sequence assembly. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1660. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Wyk B-E, Wink W. Medicinal Plants of the World. Pretoria: Briza Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Senkoro AM, Shackleton CM, Voeks RA, Ribeiro AI. Uses, knowledge, and management of the threatened pepper-bark tree (Warburgia salutaris) in southern Mozambique. Econ. Bot. 2019;73:304–324. doi: 10.1007/s12231-019-09468-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hannweg K, Sippel A, Hofmeyr M, Swemmer L, Froneman W. Strategies for the conservation of Warburgia salutaris (family: Canellaceae), a red data list species - development of propagation methods. Acta Hortic. 2016;1125:33–40. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2016.1125.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dlamini, T. S. & Dlamini, G. M. Swaziland in Southern African Plant Red Data Lists (ed. Golding, J. S.) 121–134 (National Botanic Institute, 2002).

- 51.Maroyi A. Community attitudes towards the reintroduction programme for the endangered pepperbark tree Warburgia salutaris: implications for plant conservation in south-east Zimbabwe. Oryx. 2012;46:213–218. doi: 10.1017/S0030605311000767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veeman MM, Cocks ML, Muwonge F, Chonge SK, Campbell BM. Markerts for three bark products in Zimbabwe: a case study of markets for Adansonia digitata, Berchemia discolor and Warburgia salutaris. In: Cunningham AB, Campbell BM, Luckert MK, editors. Bark Use, Management and Commerce in Africa. New York: The New York Botanical Garden Press; 2014. pp. 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Veeman TS, Cunningham AB, Kozanayo W. The economics of production of rare medicinal species introduced in southwestern Zimbabwe: Warburgia salutaris. In: Cunningham AB, Campbell BM, Luckert MK, editors. Bark Use, Management and Commerce in Africa. New York: The New York Botanical Garden Press; 2014. pp. 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Msekandiana, G. & Mlangeni, E. Malawi in Southern African Plant Red Data Lists (ed. Golding, J. S.) 135–156 (National Botanic Institute, 2002).

- 55.Jansen, P. C. M. & Mendes, O. Plantas medicinais: seu uso tradicional em Moçambique (Imprensa do Partido, 1990).

- 56.Coates-Palgrave M. Trees of Southern Africa. Cape Town: Struik Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hilton-Taylor, C., Scott-Shaw, R., Burrows, J. & Hahn N. Warburgia salutaris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 1998.10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T30364A9541142.en. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- 58.Izidine, S. & Bandeira, S. O. Mozambique in Southern African Plant Red Data Lists (ed. Golding, J. S.) 43–60 (National Botanic Institute, 2002).

- 59.Mapaura, A. & Timberlake, J. R. Zimbabwe in Southern African Plant Red Data Lists (ed. Golding, J. S.) 158–182 (National Botanic Institute, 2002).

- 60.Maroyi A. Ethnobotanical study of two threatened medicinal plants in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2008;4:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 61.William VL, Witkowski ETF, Balkwill K. Relationship between bark thickness and diameter at the breast height for six tree species used medicinally in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2007;73:449–465. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2007.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Muchugi A, et al. Genetic structuring of important medicinal species of genus Warburgia as revealed by AFLP analysis. Tree Genet. Genomes. 2008;4:787–795. doi: 10.1007/s11295-008-0151-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hannweg, K., Hofmeyer, M. & Grove, T. The pepperbark initiative: are we closer to efficiently propagating Warburgia salutaris?https://www.sanparks.org/assets/docs/conservation/scientific_new/savanna/ssnm2015/the-pepperbark-initiative-are-we-any-closer-to-efficiently-propagating-warburgia-salutaris.pdf (2015). Accessed 13 May 2020.

- 64.Tonguç M, Griffiths PD. Genetic relationships of Brassica vegetables determined using database derived simple sequence repeats. Euphytica. 2004;137:193–201. doi: 10.1023/B:EUPH.0000041577.84388.43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao X, Ma Y, Sun W, Wen X, Milne R. High genetic diversity and low differentiation of Michelia coriacea (Magnoliaceae), a critically endangered endemic in Southeast Yunnan, China. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13:4396–4411. doi: 10.3390/ijms13044396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Paliwal R, et al. Development of genomic simple sequence repeats (g-SSR) markers in Tinospora cordifolia and their application in diversity analyses. Plant Genes. 2016;5:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.plgene.2016.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tian Z, Zhang F, Liu H, Gao Q, Chen S. Development of SSR markers for a Tibetan medicinal plant, Lancea tibetica (Phrymaceae), based on RAD sequencing. Appl. Plant Sci. 2016;4:1600076. doi: 10.3732/apps.1600076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li Z-Z, Gichira AW, Wang Q-F, Che JM. Genetic diversity and population structure of the endangered basal angiosperm Brasenia schreberi (Cabombaceae) in China. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5296. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li X, et al. De novo transcriptome assembly and population genetic analyses for an endangered Chinese endemic Acer miaotaiense (Aceraceae) Genes. 2018;9:378. doi: 10.3390/genes9080378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martins S, et al. Western European wild landraces hazelnuts evaluated by SSR markers. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2015;33:1712–1720. doi: 10.1007/s11105-015-0867-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gacheri N, Wanjala BW, Jamnadass R, Muchugi A. Analysis of the impact of domestication of Warburgia ugandensis (Sprague) on its genetic diversity based on amplified fragment length polymorphism. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2016;15:1673–1680. doi: 10.5897/AJB2016.15282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Bennett MD, Leitch IJ. Evolution of genome size in the angiosperms. Am. J. Bot. 2003;90:1596–1603. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.11.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leitch IJ, Hanson L. DNA C-values in seven families fill phylogenetic gaps in the basal angiosperms. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2002;140:175–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1095-8339.2002.00096.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cueva-Agila A, et al. Genetic characterization of fragmented populations of Cinchona officinalis L. (Rubiaceae), a threatened tree of the northern Andean cloud forests. Tree Genet Genomes. 2019;15:81. doi: 10.1007/s11295-019-1393-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang S, Xue S, Kang W, Qian Z, Yi Z. Genetic diversity and population structure of Miscanthus lutarioriparius, an endemic plant of China. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0211471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.George S, Sharma J, Yadon VL. Genetic diversity of the endangered and narrow endemic Piperia yadonii (Orchidaceae) assessed with ISSR polymorphisms. Am. J. Bot. 2009;96:2022–2030. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Muriira NG, Muchugi A, Yu A, Xu J, Li A. Genetic differentiation and strong population structure in Calotropis plants. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:7832. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26275-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vardareli N, Doğaroğlu T, Doğaç E, Taşkın V, Taşkı BG. Genetic characterization of tertiary relict endemic Phoenix theophrasti population in Turkey and Phylogenetic relations of the species with other palm species revealed by SSR markers. Plant Syst. Evol. 2019;305:415–429. doi: 10.1007/s00606-019-01580-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun R, Lin F, Huang P, Zheng Y. Moderate genetic diversity and genetic differentiation in the relict tree Liquidambar formosana Hance revealed by genic simple sequence repeat markers. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1411. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Paul J, Budd C, Freeland JR. Conservation genetics of an endangered orchid in eastern Canada. Conserv. Genet. 2013;1:195–204. doi: 10.1007/s10592-012-0443-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yuan J-H, Cheng F-Y, Zhou S-L. The phylogeographic structure and conservation genetics of the endangered tree peony, Paeonia rockii (Paeoniaceae), inferred from chloroplast gene sequences. Conserv. Genet. 2011;12:1539–1549. doi: 10.1007/s10592-011-0251-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matthew WS, van Wyk AE, van Rooyen N, Botha GA. Vegetation of the Tembe Elephant Park, Maputaland, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2001;67:573–594. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6299(15)31188-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Joseph GS, et al. Large termitaria act as refugia for tall trees, deadwood and cavity-using birds in a miombo woodland. Landsc. Ecol. 2011;26:439–448. doi: 10.1007/s10980-011-9572-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ge X-J, Zhang L-B, Yuan Y-M, Hao G, Chiang T-Y. Strong genetic differentiation of the East Himalayan Megacodon stylophorus (Gentianaceae) detected by Inter-Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSR) Biodivers. Conserv. 2005;14:849–861. doi: 10.1007/s10531-004-0655-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zheng W, Wang L, Meng L, Liu J. Genetic variation in the endangered Anisodus tanguticus (Solanaceae), an alpine perennial endemic to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Genetica. 2008;132:123–129. doi: 10.1007/s10709-007-9154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Halafo, J. Estudo da Planta Warburgia salutaris na floresta de Licuati: estado de conservação e utilização pelas comunidades locais. (Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, 1996).

- 87.Governo do Distrito de Matutuine (GDM). Plano estratégico do desenvolvimento do distrito de Matutuine (2009–2013) (Governo do Distrito de Matutuine, 2008).

- 88.Ministério de Administração Estatal (MAE). Perfil do distrito de Namaacha, província de Maputo. Portal do Governo de Moçambique. https://www.portaldogoverno.gov.mz/Informacao/distritos/ (2005). Accessed 13 May 2020.

- 89.Mbambezeli, G. Mbambezeli, G., Warburgia salutaris (Bertol.f.) Chiov. https://pza.sanbi.org/ (2004).

- 90.Pan L, et al. Genetic diversity among germplasms of Pitaya based on SSR markers. Sci. Hortic. 2017;225:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.06.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ministério de Administração Estatal (MAE). Perfil do distrito de Matutuine, província de Maputo. Portal do Governo de Moçambique.https://www.portaldogoverno.gov.mz/Informacao/distritos/ (2005). Accessed 13 May 2020.

- 92.Kirkwood, D. Southeastern Africa: Mozambique, Swaziland, and So. Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forests.https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/at0119 (2014). Accessed 13 May 2020.

- 93.Burrows J, Burrows S, Lotter M, Schmidt E. Trees and Shrubs: Mozambique. Cape Town: Print Matters Heritage; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Izidine SA. Licuáti Forestry Reserve, Mozambique: Flora, Utilization and Conservation. Pretoria: University of Pretoria; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moll EJ. Terrestrial plant ecology. In: Bruton MN, Cooper KH, editors. Studies on the Ecology of Maputaland. Cape Town: Cape and Transvaal Printers (Pty) Ltd; 1980. pp. 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ministerio de Turismo (MITUR). Proposta de demarcação do Corredor de Futi.https://conservationcorridor.org/cpb/Transfrontier_Conservation_Areas_2002.pdf (2002). Accessed 13 May 2020.

- 97.van Rooyen N. Die plantegroei van die Roodeplaatdam-natuurreservaat II. Die plantgemeenskappe. South-Africa Tydskrif Plant. 1983;2:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Estatísticas do distrito de Namaacha (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2013).

- 99.Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Estatísticas do distrito de Matutuine (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2013).

- 100.Loureiro J, Rodriguez E, Doležel J, Santos C. Two new nuclear isolation buffers for plant DNA flow cytometry: a test with 37 species. Ann. Bot. 2007;100:875–888. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Guilengue N, Alves S, Talhinhas P, Neves-Martins J. Genetic and genomic diversity in a Tarwi (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet) germplasm collection and adaptability to Mediterranean climatic conditions. Agronomy. 2020;10:2. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Doležel J, Sgorbati S, Lucretti S. Comparison of three DNA fluorochromes for flow cytometric estimation of nuclear DNA content in plants. Physiol. Plant. 1992;85:625–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb04764.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Doležel J, Bartoš J. Plant DNA flow cytometry and estimation of nuclear genome size. Ann. Bot. 2005;95:99–110. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Peakall R, Smouse PE. GENALEX 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2006;6:288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Benor S, Zhang M, Wang Z, Zhang H. Assessment of genetic variation in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) inbred lines using SSR molecular markers. J. Genet. Genomics. 2008;35:373–379. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chesnokov YV, Artemyeva AM. Evaluation of the measure of polymorphism information of genetic diversity. Agric. Biol. 2015;50:571–578. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Botstein D, White RL, Skolnick MS, Davis RW. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1980;62:314–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Earl DA, vonHoldt BM. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2012;4:359–361. doi: 10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA. CLUMPP: a cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with labels switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure. Bioinformatics. 2007;15:1801–1806. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nei M. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics. 1978;89:583–590. doi: 10.1093/genetics/89.3.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gower JC. Some distance properties of latent root and vector methods used in multivariate analysis. Biometrika. 1966;53:325–338. doi: 10.1093/biomet/53.3-4.325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Langella, O. Populations, 1.2.30 (CNRS UPR9034, 1999).

- 115.Wright S. Evolution and the Genetics of Populations: Variability Within and Among Natural Populations. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.