Abstract

Background

A large proportion of individuals who use heroin report initiating opioid use with prescription opioids. However, patterns of prescription opioid use preceding heroin-related overdose have not been described.

Objective

To describe prescription opioid use in the year preceding heroin overdose.

Design

Case-control study comparing prescription opioid use with a heroin-involved overdose, non-heroin-involved opioid overdose, and non-overdose controls from 2015 to 2017.

Participants

Oregon Medicaid beneficiaries with linked administrative claims, vital statistics, and prescription drug monitoring program data.

Main Measures

Opioid, benzodiazepine, and other central nervous system depressant prescriptions preceding overdose; among individuals with one or more opioid prescription, we assessed morphine milligram equivalents per day, overlapping prescriptions, prescriptions from multiple prescribers, long-term use, and discontinuation of long-term use.

Key Results

We identified 1458 heroin-involved overdoses (191 fatal) and 2050 non-heroin-involved opioid overdoses (266 fatal). In the 365 days prior to their overdose, 45% of individuals with a heroin-involved overdose received at least one prescribed opioid compared with 78% of individuals who experienced a non-heroin-involved opioid overdose (p < 0.001). For both heroin- and non-heroin-involved overdose cases, the likelihood of receiving an opioid increased with age. Among heroin overdose cases with an opioid dispensed, the rate of multiple pharmacy use was the only high-risk opioid pattern that was greater than non-overdose controls (adjusted odds ratio 3.2; 95% confidence interval 1.48 to 6.95). Discontinuation of long-term opioid use was not common prior to heroin overdose and not higher than discontinuation rates among non-overdose controls.

Conclusions

Although individuals with a heroin-involved overdose were less likely to receive prescribed opioids in the year preceding their overdose relative to non-heroin opioid overdose cases, prescription opioid use was relatively common and increased with age. Discontinuation of long-term prescription opioid use was not associated with heroin-involved overdose.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-020-06192-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: prescription opioids, heroin, overdose

INTRODUCTION

The opioid epidemic has evolved over the last decade, shifting from being primarily related to prescription opioids (natural or semi-synthetic opioids) to heroin and illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids.1,2 Between 2008 and 2017, the rate of overdose deaths involving prescription opioids (natural or semi-synthetic opioids) increased 47% from 3.0 to 4.4 per 100,000.2 In contrast, deaths involving heroin increased nearly fivefold from 1 to 4.9 deaths per 100,000 during the same period.2 Heroin and synthetic opioids now account for the majority of all opioid-related fatalities in the USA.2

In contrast to the heroin epidemic of the 1960s, the recent rise in heroin use and overdose is closely related to the prescription opioid epidemic.3,4 Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicate that currently more than 80% of individuals who use heroin report initiating opioid use with prescription pain relievers.4,5 Expanding markets of lower cost, higher purity heroin can explain some of this transition.6 The epidemic continues to evolve and recent trends indicate the number of individuals who initiate opioid use with heroin has increased from 9% in 2005 to 32% in 2015.7 Despite this, there are growing concerns that efforts to reduce or place limits on opioid prescribing may be associated with substitution with other opioids including heroin. Epidemiologic trends in opioid overdose and studies of the abuse deterrent reformulation of oxycodone provide ecologic evidence suggesting that as prescription opioids become more difficult to misuse, individuals may substitute with other illicit opioids such as heroin.8–11

Despite being a purported gateway to heroin, little is known about patterns of prescription opioid use that predict the transition. Opioid dispensing patterns that increase the risk for overdose (e.g., high dose, benzodiazepine co-prescribing) are well documented.12 However, the extent to which these high-risk patterns are also present prior to heroin overdose is unclear. It is important to understand if these same predictors exist because 70% of individuals who report using heroin in the past year also report using prescription opioids.5 Furthermore, because disruption in access to prescribed opioids may hasten heroin use and overdose, other patterns that suggest discontinuation or dose reduction need to be explored. The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between opioid dispensing patterns (including high-risk use and discontinuation) and heroin overdose.

METHODS

Data Sources

We conducted a case-control study to investigate the relationship between opioid dispensing patterns and heroin-involved overdose. Our analytic data source was linked data from Oregon’s Medicaid, vital statistics (death certificate data), and prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) from 2014 to 2017. Oregon Medicaid claims data were linked to PDMP data using a previously described probabilistic linkage based on patient name, date of birth, and zip code.13,14 We linked vital statistics and Medicaid data using social security number.

Case Definitions

Cases comprised individuals with a fatal or non-fatal heroin-involved overdose between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2017. We used vital statistics to identify individuals with a fatal overdose with an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) 10th revision code indicating heroin involvement (S1 Table). To identify non-fatal overdoses, we used Medicaid medical claims data to identify emergency department (ED) encounters or hospitalizations with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for heroin-involved poisoning (any diagnosis code position). We selected the first overdose (fatal or non-fatal) as the case index event. If fatal and non-fatal events occurred on the same day, the case was designated as fatal.

We first compared heroin-involved overdose cases to opioid overdose cases that did not involve heroin. Similar to heroin-involved overdose cases, we used vital statistics and Medicaid claims data to identify non-heroin fatal and non-fatal opioid overdoses respectively (S2 Table). We excluded fatalities that reported an ICD-10 code indicating synthetic opioids (T40.4) because rates of overdose involving illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids in Oregon have been relatively low.15 We also excluded T40.6 (other and unspecified narcotics) because of a lack of specificity.

Exposures

We used Oregon’s PDMP data to identify controlled substance dispensing in the year preceding each patient’s index date. We characterized patterns of dispensing for opioids (excluding buprenorphine), benzodiazepines, and other central nervous system (CNS) depressants (i.e., carisoprodol, eszopiclone, suvorexant, zaleplon, zolpidem), using National Drug Codes.16 The complete list of drugs is summarized in S3 Table. For individuals with an overdose (heroin and non-heroin), our primary analysis characterized the proportion of individuals with an opioid, benzodiazepine, or other CNS depressant medication dispensed within 7, 30, 90, and 365 days of their overdose date.

Patterns of Opioid Dispensing

A secondary objective was to investigate specific opioid dispensing patterns among all opioid overdose cases (heroin involved and not involved) relative to individuals with one or more dispensed opioid who did not have an overdose (non-overdose controls). To increase comparability, we restricted overdose cases to those with one or more dispensed opioid in the year preceding their overdose. For each heroin-involved overdose case with an opioid dispensed in the year prior to overdose, we randomly selected four non-overdose control patients who had an opioid dispensed in the year preceding each case’s overdose date. Controls were matched on sex and age (in 10-year bins: < 20; 20–29; 30–39; 40–49; 50–59; ≥ 60 years). We assigned the case’s index date (overdose date) to each of their respective four controls to ensure that the exposure periods included the same calendar time period.

Within the subset of individuals with an opioid dispensed in the year before their index date, we compared high-risk dispensing patterns in those with a heroin-involved overdose to the non-overdose control group. High-risk opioid dispensing patterns included opioid-opioid overlap, opioid-benzodiazepine overlap, and opioid-non-benzodiazepine sedative overlap. Using dates and days’ supply variables in PDMP data, we identified overlap in cases in which two or more prescriptions overlapped by one or more days. We identified multiple provider episodes defined by having four or more prescribers or four or more pharmacies in a 180-day period.17 We also identified patients whose average opioid daily dose was more than 90 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) by dividing each patient’s total MME over the year by the number of opioid days’ supply dispensed in the year.16 We considered each prescription independently to estimate an average dose per day across all dispensed prescriptions.16

Finally, we explored the relationship between heroin-involved overdose and prescription opioid discontinuation among individuals who were on long-term opioid therapy prior to their index date. In the year preceding each individual’s index date, we first identified those who had 90 or more consecutive days (without gaps) with an opioid available using dispensing dates and days’ supply. Among individuals who had multiple 90-day episodes, we selected the first episode chronologically. We defined discontinuation of therapy if the individual had 45 or more consecutive days without an opioid dispensing after their 90-day continuous therapy episode.

Analysis

For our primary analysis, we compared antecedent opioid dispensing patterns for patients with a heroin-involved overdose to patients with a non-heroin opioid overdose by overdose disposition (fatal vs non-fatal), demographics (age, race, sex), and comorbidity. To characterize comorbidity, we used conditions and coding defined in the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index.18

Univariate comparisons were analyzed using chi-square, parametric, and non-parametric statistical tests as appropriate for categorical or continuous variables. To evaluate the relationship between opioid dispensing patterns and heroin involvement, we also used multivariate logistic regression analysis to control for demographics and comorbidity reporting both crude and adjusted odds ratios. We examined opioid dispensing pattern heterogeneity within demographic or overdose disposition subgroups (sex, age, urban/rural, year of overdose, fatal/non-fatal) using tests of interaction to determine if opioid dispensing patterns differed between these groups.

In a secondary analysis, we compared high-risk dispensing patterns in heroin-involved overdose cases with an opioid dispensed in the year preceding overdose to matched non-overdose controls using both univariate statistics and conditional multivariate logistic regression. We included variables in the multivariate models that were significant at the 0.25 level for univariate comparisons. We also report the subset of non-heroin opioid overdose cases which had an opioid dispensed in the prior year as a qualitative contrast. To ensure complete capture of comorbidity diagnoses, we re-analyzed multivariate logistic regression models restricting to individuals who had continuous Medicaid enrollment for the year preceding their index event. We conducted our statistical analysis using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

We obtained Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval before obtaining the data. The data were pre-existing de-identified health claims data, so we did not need to obtain informed consent.

RESULTS

Between 2015 and 2017, we identified 3508 individuals who experienced a fatal (n = 457, 13%) or non-fatal (n = 3051, 87%) opioid overdose. As summarized in Table 1, 1458 individuals had an overdose with a diagnosis or contributing cause involving heroin and 2050 did not. Compared with individuals with a non-heroin opioid overdose, individuals with heroin-involved overdose were more likely to be male (68% vs 38%; p < 0.001), live in an urban area (78% vs 62%; p < 0.001), and be younger than 30 years of age (45% vs 22%; p < 0.001). Individuals with heroin-involved overdose were less likely to be White (55% vs 63%; p < 0.001), though missing data were substantial. With the exception of misuse of alcohol (28% vs 20%; p < 0.001) and drugs (80% vs 49%; p < 0.001), individuals with heroin involvement had fewer comorbid conditions compared to those without heroin involvement (3.1 vs 4.3; p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and Comorbid Diagnoses for Individuals with Opioid-Related Overdose

| Heroin involved | Non-heroin involved | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1458 | 2050 | |

| Overdose | 0.91 | ||

| Fatal | 191 (13.1) | 266 (13.0) | |

| Non-fatal | 1267 (86.9) | 1784 (87.0) | |

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||

| Female | 472 (32.4) | 1270 (62.0) | |

| Male | 986 (67.6) | 780 (38.1) | |

| Race | < 0.001 | ||

| White | 805 (55.2) | 1284 (62.6) | |

| Black | 35 (2.4) | 79 (3.9) | |

| Asian | 6 (0.4) | 13 (0.6) | |

| Native American | 31 (2.1) | 56 (2.7) | |

| Other | 119 (8.2) | 105 (5.1) | |

| Unknown | 462 (31.7) | 513 (25.0) | |

| ZIP code designation | < 0.001 | ||

| Urban | 1140 (78.2) | 1260 (61.5) | |

| Rural | 318 (21.8) | 790 (38.5) | |

| Age in years | < 0.001 | ||

| < 30 | 654 (44.9) | 456 (22.2) | |

| 30–49 | 597 (41.0) | 814 (39.7) | |

| ≥ 50 | 207 (14.2) | 780 (38.1) | |

| Elixhauser diagnoses | |||

| AIDS | 12 (0.8) | 21 (1.0) | 0.54 |

| Alcohol misuse | 406 (27.8) | 408 (19.9) | < 0.001 |

| Deficiency anemia | 115 (7.9) | 327 (16.0) | < 0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 22 (1.5) | 129 (6.3) | < 0.001 |

| Blood loss anemia | 8 (0.5) | 47 (2.3) | < 0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 33 (2.3) | 166 (8.1) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 241 (16.5) | 702 (34.2) | < 0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 49 (3.4) | 98 (4.8) | 0.04 |

| Depression | 408 (28.0) | 954 (46.5) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 42 (2.9) | 129 (6.3) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 37 (2.5) | 225 (11.0) | < 0.001 |

| Drug misuse | 1163 (79.8) | 1007 (49.1) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 223 (15.3) | 769 (37.5) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, complicated | 3 (0.2) | 17 (0.8) | 0.02 |

| Hypothyroidism | 37 (2.5) | 208 (10.1) | < 0.001 |

| Liver disease | 263 (18.0) | 307 (15.0) | 0.02 |

| Lymphoma | 3 (0.2) | 14 (0.7) | 0.05 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 278 (19.1) | 595 (29.0) | < 0.001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 3 (0.2) | 44 (2.1) | < 0.001 |

| Other neurological disorders | 537 (36.8) | 783 (38.2) | 0.44 |

| Obesity | 64 (4.4) | 419 (20.4) | < 0.001 |

| Paralysis | 9 (0.6) | 64 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 22 (1.5) | 124 (6) | < 0.001 |

| Psychoses | 325 (22.3) | 613 (29.9) | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 23 (1.6) | 70 (3.4) | < 0.001 |

| Renal failure | 27 (1.9) | 153 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 1 (0.1) | 77 (3.8) | < 0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 2 (0.1) | 30 (1.5) | < 0.001 |

| Valvular disease | 43 (2.9) | 81 (4) | 0.11 |

| Weight loss | 53 (3.6) | 136 (6.6) | < 0.001 |

| Average no. conditions (SD) | 3.1 (2.5) | 4.3 (3.2) | < 0.001 |

Percentages are in parentheses

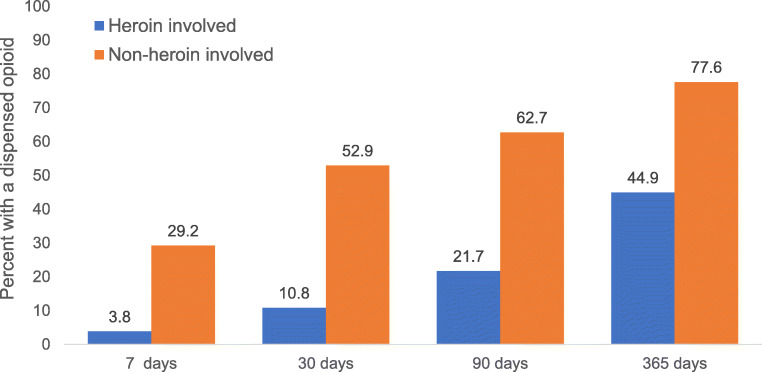

Figure 1 summarizes opioid dispensing patterns within 7, 30, 90, and 365 days of an individual’s overdose date. In the year prior to overdose, 45% of heroin-involved overdose cases had an opioid dispensed to them compared with 78% of non-heroin opioid overdose cases (p < 0.001). While opioid dispensing was lower among heroin-involved overdose cases compared with non-heroin opioid overdoses at all time intervals, the difference was particularly large in the 7 days (4% vs 29%; p < 0.001) and 30 days (11% vs 53%; p < 0.001) prior to overdose. The use of benzodiazepines (18% vs 42%; p < 0.001) and other CNS depressants (4% vs 12%; p < 0.001) was also less common among heroin-involved cases in the 365 days preceding overdose (S4 Table).

Figure 1.

Opioid dispensing in the 7, 30, 90, and 365 days preceding opioid overdose; all differences statistically significant (p < 0.001).

As shown in Table 2, the association between opioid dispensing patterns and heroin-involved overdose did not differ significantly across subgroups. In general, individuals with an opioid overdose that did not involve heroin were consistently more likely to have an opioid dispensed across all subgroups analyzed. Although the proportion of heroin-involved overdose cases with a dispensed opioid for individuals age 50 and over was nearly twice that of individuals less than 30, this trend was similar for overdose cases that did not involve heroin (the test of interaction p = 0.67).

Table 2.

Percentage of Overdose Cases with a Dispensed Opioid in the Year Preceding Overdose by Demographic Subgroup

| Heroin involved | Non-heroin involved | Crude OR (95% CI) | Interaction p value | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Interaction p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall percentage | 44.9 | 77.6 | 0.24 (0.20, 0.27) | 0.43 (0.36, 0.51) | ||

| By sex | 0.81 | 0.80 | ||||

| Female | 49.8 | 79.8 | 0.25 (0.20, 0.32) | 0.43 (0.33, 0.56) | ||

| Male | 42.6 | 74.0 | 0.26 (0.21, 0.32) | 0.41 (0.33, 0.52) | ||

| By age category | 0.39 | 0.67 | ||||

| < 30 | 36.2 | 63.4 | 0.33 (0.26, 0.42) | 0.47 (0.36, 0.63) | ||

| 30–49 | 49.6 | 78.5 | 0.27 (0.21, 0.34) | 0.4 (0.31, 0.53) | ||

| ≥ 50 | 58.9 | 84.9 | 0.26 (0.18, 0.36) | 0.41 (0.27, 0.61) | ||

| By urbanicity | 0.04 | 0.18 | ||||

| Urban | 45.0 | 75.4 | 0.27 (0.22, 0.32) | 0.46 (0.38, 0.57) | ||

| Rural | 44.7 | 81.0 | 0.19 (0.14, 0.25) | 0.35 (0.25, 0.49) | ||

| Race | 0.81 | 0.37 | ||||

| White | 48.2 | 79.3 | 0.24 (0.20, 0.29) | 0.46 (0.36, 0.58) | ||

| Other | 40.9 | 74.7 | 0.23 (0.19, 0.29) | 0.39 (0.3, 0.51) | ||

| Year | 0.49 | 0.83 | ||||

| 2015 | 46.8 | 77.1 | 0.26 (0.20, 0.33) | 0.46 (0.34, 0.61) | ||

| 2016 | 45.8 | 80.1 | 0.21 (0.16, 0.27) | 0.40 (0.3, 0.55) | ||

| 2017 | 41.9 | 75.4 | 0.24 (0.18, 0.3) | 0.43 (0.31, 0.58) | ||

| Fatality | 0.47 | 0.32 | ||||

| Yes | 41.4 | 77.4 | 0.21 (0.14, 0.31) | 0.35 (0.22, 0.55) | ||

| No | 45.5 | 77.6 | 0.24 (0.21, 0.28) | 0.45 (0.37, 0.54) |

p values reflect subgroup differences between overdose type

*Logistic regression models adjusted for sex, race, urbanicity, age category, and the following Elixhauser comorbidities: alcohol misuse; deficiency anemia; rheumatoid arthritis; blood loss anemia; congestive heart failure; chronic lung disease; coagulopathy; depression; diabetes, uncomplicated; diabetes, complicated; drug misuse; hypertension, uncomplicated; hypertension, complicated; hypothyroidism; liver disease; lymphoma; fluid and electrolyte disorders; metastatic cancer; obesity; paralysis; peripheral vascular disorders; psychoses; pulmonary circulation disorders; renal failure; solid tumor without metastasis; peptic ulcer disease; valvular disease; weight loss

Opioid Dispensing Patterns

In Table 3, we summarize demographics and comorbid conditions among overdose cases (with and without heroin involvement) and age- and sex-matched non-overdose controls with one or more opioids dispensed in the year preceding their index date. We specifically compared heroin-involved overdose cases (n = 655) to age- and sex-matched non-overdose controls with one or more dispensed opioids (n = 2620). Relative to non-overdose controls, heroin-involved overdose cases were more likely to be White (59% vs 55%; p = 0.027) and live in an urban area (78% vs 60%; p < 0.001). Although individuals with a heroin-involved overdose had fewer comorbid diagnoses than overdose cases without heroin involvement, they had more comorbid diagnoses than non-overdose controls (3.7 vs 0.9; p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Demographic and Comorbid Diagnoses Among Individuals with an Opioid Overdose (with and without Heroin Involvement) and Age- and Sex-Matched Non-overdose Controls with One or More Opioid Dispensed in the Year Preceding Index Date

| Non-heroin involved | Heroin involved | Non-overdose | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1590 | 655 | 2620 | |

| Overdose | ||||

| Fatal | 206 (13.0) | 79 (12.1) | NA | |

| Non-fatal | 1384 (87.0) | 576 (87.9) | NA | |

| Sex | 1.000 | |||

| Female | 1013 (63.7) | 235 (35.9) | 940 (35.9) | |

| Male | 577 (36.3) | 420 (64.1) | 1680 (64.1) | |

| Race | .027 | |||

| White | 1018 (64.0) | 388 (59.2) | 1447 (55.2) | |

| Black | 52 (3.3) | 21 (3.2) | 54 (2.1) | |

| Asian | 9 (0.6) | 3 (0.5) | 38 (1.5) | |

| Native American | 50 (3.1) | 16 (2.4) | 52 (2.0) | |

| Other | 70 (4.4) | 41 (6.3) | 210 (8.0) | |

| Unknown | 391 (24.6) | 186 (28.4) | 819 (31.3) | |

| ZIP designation | < .001 | |||

| Urban | 950 (59.8) | 513 (78.3) | 1568 (59.9) | |

| Rural | 640 (40.3) | 142 (21.7) | 1052 (40.2) | |

| Age | 1.000 | |||

| < 30 | 289 (18.2) | 237 (36.2) | 948 (36.2) | |

| 30–49 | 639 (40.2) | 296 (45.2) | 1184 (45.2) | |

| ≥ 50 | 662 (41.6) | 122 (18.6) | 488 (18.6) | |

| Elixhauser diagnoses | ||||

| AIDS | 16 (1.0) | 7 (1.1) | 5 (0.2) | .004 |

| Alcohol misuse | 320 (20.1) | 212 (32.4) | 149 (5.7) | < .001 |

| Deficiency anemia | 288 (18.1) | 72 (11.0) | 78 (3.0) | < .001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 117 (7.4) | 20 (3.1) | 42 (1.6) | .015 |

| Blood loss anemia | 40 (2.5) | 4 (0.6) | 28 (1.1) | .287 |

| Congestive heart failure | 146 (9.2) | 18 (2.7) | 22 (0.8) | < .001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 571 (35.9) | 152 (23.2) | 253 (9.7) | < .001 |

| Coagulopathy | 88 (5.5) | 29 (4.4) | 27 (1.0) | < .001 |

| Depression | 770 (48.4) | 238 (36.3) | 286 (10.9) | < .001 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 112 (7.0) | 28 (4.3) | 54 (2.1) | .001 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 198 (12.5) | 28 (4.3) | 64 (2.4) | .011 |

| Drug abuse | 761 (47.9) | 515 (78.6) | 202 (7.7) | < .001 |

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 663 (41.7) | 147 (22.4) | 287 (11.0) | < .001 |

| Hypertension, complicated | 14 (0.9) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.04) | .104 |

| Hypothyroidism | 181 (11.4) | 27 (4.1) | 77 (2.9) | .122 |

| Liver disease | 257 (16.2) | 165 (25.2) | 58 (2.2) | < .001 |

| Lymphoma | 13 (0.8) | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.04) | .027 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 492 (30.9) | 163 (24.9) | 87 (3.3) | < .001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 41 (2.6) | 3 (0.5) | 9 (0.3) | .716 |

| Other neurological disorders | 605 (38.1) | 276 (42.1) | 92 (3.5) | < .001 |

| Obesity | 372 (23.4) | 42 (6.4) | 209 (8.0) | .178 |

| Paralysis | 58 (3.7) | 8 (1.2) | 11 (0.4) | .037 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 106 (6.7) | 16 (2.4) | 27 (1.0) | .004 |

| Psychoses | 499 (31.4) | 178 (27.2) | 164 (6.3) | < .001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 60 (3.8) | 13 (2.0) | 7 (0.3) | < .001 |

| Renal failure | 135 (8.5) | 21 (3.2) | 20 (0.8) | < .001 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 66 (4.2) | 1 (0.2) | 20 (0.8) | .100 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 25 (1.6) | 2 (0.3) | 11 (0.4) | 1.000 |

| Valvular disease | 72 (4.5) | 25 (3.8) | 17 (0.7) | < .001 |

| Weight loss | 115 (7.2) | 33 (5.0) | 43 (1.6) | < .001 |

| Average no. conditions (SD) | 4.5 (3.3) | 3.7 (2.8) | 0.9 (1.6) | < .001 |

p values reflect differences between heroin-involved overdose and non-overdose controls

Table 4 summarizes the prevalence of opioid dispensing patterns known to increase the risk of overdose. In the univariate analysis, several opioid dispensing patterns were significantly more prevalent among heroin-involved overdose cases compared with matched controls. After statistical adjustment, only multiple pharmacy episodes remained statistically significant (aOR 3.21; 95% CI 1.48 to 6.95). High-risk opioid dispensing patterns were uniformly more prevalent among non-heroin overdose cases compared with both heroin-involved cases and non-overdose controls.

Table 4.

Opioid Dispensing Patterns Among Individuals with an Opioid Overdose (with and without Heroin Involvement) and Age- and Sex-Matched Non-overdose Controls with One or More Opioid Dispensed in the Year Preceding Index Date. Crude and Adjusted Odds Ratios Reflect Conditional Logistic Regressions Comparing Heroin-Involved Overdose Cases and Matched Control Group

| Non-heroin involved | Heroin involved | Non-overdose | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)‡ | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1590 | 655 | 2620 | |||

| Average number of opioid prescriptions dispensed, M (SD) | 11.9 (11.7) | 4.5 (6.0) | 3.3 (5.3) | 1.03 (1.02, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) | .83 |

| Average MME per day, M (SD) | 55.9 (49.1) | 43.6 (31.7) | 39.4 (26.6) | 1.05 (1.02, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.09) | .48 |

| Any opioid over 90 MME per day | 224 (14.1) | 37 (5.7) | 101 (3.9) | 1.49 (1.01, 2.19) | 1.62 (0.69, 3.81) | .27 |

| Overlapping prescriptions* | ||||||

| Opioid/opioid overlap | 993 (62.5) | 178 (27.2) | 482 (18.4) | 1.71 (1.39, 2.10) | 0.95 (0.63, 1.42) | .79 |

| Opioid/benzodiazepine overlap | 674 (42.4) | 113 (17.3) | 254 (9.7) | 1.97 (1.54, 2.51) | 0.80 (0.50, 1.29) | .36 |

| Opioid/sedative overlap | 185 (11.6) | 22 (3.4) | 57 (2.2) | 1.58 (0.95, 2.61) | 0.78 (0.29, 2.08) | .62 |

| Multiple prescriber episode | 503 (31.6) | 124 (18.9) | 189 (7.2) | 3.10 (2.41, 4.00) | 1.44 (0.87, 2.37) | .15 |

| Multiple pharmacy episode | 216 (13.6) | 71 (10.8) | 49 (1.9) | 6.23 (4.27, 9.08) | 3.21 (1.48, 6.95) | < .01 |

| ≥ 90 consecutive days of a dispensed opioid | 469 (29.5) | 47 (7.2) | 123 (4.7) | 1.59 (1.12, 2.27) | 1.49 (0.76, 2.89) | .24 |

| Discontinuation† | 27 (5.8) | 2 (4.3) | 10 (8.1) | 1.99 (0.42, 9.45) | 0.33 (0.03, 3.44) | 0.35 |

Statistical analyses reflect comparison between heroin-involved overdose cases and the non-overdose control group

MME morphine milligram equivalents

*One or more days of overlap

†45 consecutive days of no dispensed opioids available; odds ratios are from unconditional logistic regressions

‡Logistic regression model adjusted for race, urbanicity, and the following Elixhauser comorbidities: alcohol misuse; deficiency anemia; rheumatoid arthritis; blood loss anemia; congestive heart failure; chronic lung disease; coagulopathy; depression; diabetes, uncomplicated; diabetes, complicated; drug misuse; hypertension, uncomplicated; hypertension, complicated; hypothyroidism; liver disease; lymphoma; fluid and electrolyte disorders; metastatic cancer; obesity; paralysis; peripheral vascular disorders; psychoses; pulmonary circulation disorders; renal failure; solid tumor without metastasis; peptic ulcer disease; valvular disease; weight loss

Long-term opioid therapy was uncommon among heroin-involved overdose cases (7%) and non-overdose controls (5%). Among individuals with long-term opioid therapy, 4% of those with a heroin-involved overdose discontinued opioids prior to overdosing compared with 8% of controls (p = 0.35).

Our findings were generally similar when we restricted our sample to individuals with continuous Medicaid enrollment in the year prior to their index date (S5–S9 Tables).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically contrast opioid dispensing patterns between individuals with a heroin-involved or non-heroin-involved opioid overdose. Nearly half of individuals (45%) who experienced a heroin overdose had an opioid dispensed in the year prior to the overdose. However, opioid dispensing was less common in the period immediately preceding the overdose. Only 11% of individuals who experienced heroin overdose had an opioid dispensed in the 30 days prior to overdose. In contrast, 53% of individuals with a non-heroin opioid overdose had an opioid dispensed in the 30 days prior to overdose. Those experiencing a heroin-involved overdose were also substantially less likely to have a benzodiazepine dispense prior to overdose. With the exception of age, exposure to prescribed opioids was generally uniform across all demographic characteristics. For both heroin-involved and non-heroin overdose groups, opioid dispensing increased with age. Among individuals who were dispensed opioids prior to overdose, the only high-risk dispensing pattern that was elevated relative to non-overdose controls was controlled substances dispensed from four or more pharmacies in a 180-day period. Although long-term opioid therapy was uncommon, we found no evidence that discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy was associated with heroin-involved opioid overdose.

Our findings have several implications. First, we found a large proportion of individuals who are actively using heroin are also receiving opioids dispensed through the healthcare system. Ethnographic data suggest that individuals who inject heroin often supplement with prescription opioids.19 The source of these opioids is likely a mix of diverted and prescribed.20 Because these individuals are receiving opioids through traditional healthcare channels, there may be opportunities for clinicians to screen and engage these patients in treatment. Second, in contrast to non-heroin overdose cases, traditional high-risk opioid dispensing patterns (e.g., dose, opioid/benzodiazepine overlap) were not associated with heroin-involved overdose, suggesting alternative pathways to overdose. The possible misuse- or diversion-related indicator of multiple pharmacy use was the only dispensing pattern that remained significant in our models after statistical adjustment. Finally, we found no association between discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy and heroin-involved overdose. There are growing concerns that misapplication of patient-centered prescribing guidelines by healthcare systems, insurers, and pharmacy benefit managers may be forcing involuntary discontinuations or dose reductions that lead to harms, including overdose, suicide, or substitution with illicit opioids.21,22 In a study of over 100,000 individuals on chronic opioid therapy with commercial or Medicare Advantage coverage, Fenton et al. reported the percentage of patients tapering their dose more than doubled between 2008 and 2017.23 Emerging data suggest that rapid tapering or abrupt discontinuation of chronic opioid therapy can harm patients.24–27 Using data from the Vermont Medicaid program, Mark et al. reported that rapid opioid tapering was associated with a significant increase in opioid-related adverse events.24 Glanz et al. used a nested case-control study of people with long-term opioid therapy from a large integrated healthcare system and found that while sustained opioid discontinuation was associated with a reduced odds of opioid overdose, dosing variability, possibly reflecting attempted tapering, was associated with a significant increase in overdose.25 A recently published large cohort analysis in the Veterans Health Administration observed that discontinuing opioid therapy was associated with a significant increase in the risk of overdose or suicide and that the risk increased as the duration of opioid therapy increased.26 However, none of these studies specifically evaluated the relationship between dose reduction or discontinuation and heroin-related outcomes.

Our results have several limitations. First, this study was a case-control design which precludes firm conclusions about causality. Our study uses data from the Oregon Medicaid program and may not reflect the overdose or prescription opioid use epidemiology for other parts of the country. There is considerable variation in both opioid prescribing and rates of heroin-involved overdose across the USA.28,29 Rates of heroin-related overdose are three to five times higher in the Northeast and Midwest than Western states,30 and in 2017, Oregon had among the lowest heroin-involved overdose death rates in the country, although county-level trends vary markedly.15 We used matching and multivariate logistic regression models to control for measured confounders for our comparison of heroin-involved overdose and non-overdose controls. However, we recognize that unmeasured factors that are difficult to measure using administrative data (e.g., tobacco use, weight, socioeconomic disparities) may remain as residual confounders. We relied on Oregon Medicaid administrative claims data and vital statistics to identify overdose cases. A recent validation work suggests that administrative codes have very high predictive ability (positive predictive value = 95%; negative predictive value = 98%) for identifying heroin-involved overdose.31 Oregon has a centralized medical examiner system model to certify deaths, which has been shown to provide more consistent and specific reporting of implicated drugs.32,33 Finally, although we observed low rates of long-term opioid therapy and lower discontinuation rates, our study only captured opioid use in the year immediately preceding an overdose. Although quantitative data are sparse, findings from a community-based sample of 383 people using non-prescribed opioid analgesics suggest that the rate of heroin initiation is less than 3% per year.34 Because of the limited window of ascertainment in our study, the extent to which we can determine whether reductions in opioid prescribing contribute to new heroin use remains uncertain. Longitudinal studies with an extended follow-up period may be needed.

Although it is clear that prescription opioid misuse greatly increases the risk of, and often precedes, heroin initiation and use,5,6,35 the premise that supply-side restrictions for prescription opioids are driving the rise in heroin use and overdose is not strongly supported by the existing literature. Although we found that disruption of long-term opioid therapy was uncommon and not associated with a heroin-involved overdose, our analyses are not definitive. A growing literature suggests that disruption or discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy is associated with overdose, suicide, and other harms. As the trajectory of prescription opioid use in the country continues to decline, there is urgent need to identify harms associated with opioid dose reduction and discontinuation.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 57 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kun Zhang, PhD, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U01 CE00278).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval before obtaining the data. The data were pre-existing de-identified health claims data, so we did not need to obtain informed consent.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Hartung reports grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, during the conduct of the study and grants from National Multiple Sclerosis Society, outside the submitted work. Ms. Johnston reports grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, during the conduct of the study. Ms. Hallvik reports grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, during the conduct of the study. Ms. Leichtling reports grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, during the conduct of the study. Mr. Geddes has nothing to disclose. Dr. Hildebran reports grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Keast reports grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, during the conduct of the study, grants from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and grants from Amgen, outside the submitted work. Dr. Chan has nothing to disclose. Dr. Korthuis reports grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, during the conduct of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jalal H, Buchanich JM, Roberts MS, Balmert LC, Zhang K, Burke DS. Changing dynamics of the drug overdose epidemic in the United States from 1979 through 2016. Science. 2018:21:361(6408). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Hedegaard H, Minino AM, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS data brief 2018:1–8. [PubMed]

- 3.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between Nonmedical Prescription-Opioid Use and Heroin Use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1508490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA psychiatry. 2014;71:821–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones CM. Heroin use and heroin use risk behaviors among nonmedical users of prescription opioid pain relievers - United States, 2002-2004 and 2008-2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciccarone D. The triple wave epidemic: Supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;71:183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Cicero TJ, Kasper ZA, Ellis MS. Increased use of heroin as an initiating opioid of abuse: Further considerations and policy implications. Addict Behav. 2018;87:267–71. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell D, Alpert A, Pacula RL. A Transitioning Epidemic: How The Opioid Crisis Is Driving The Rise In Hepatitis C. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2019;38:287–294. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS. Abuse-Deterrent Formulations and the Prescription Opioid Abuse Epidemic in the United States: Lessons Learned From OxyContin. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:424–430. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Harney J. Shifting Patterns of Prescription Opioid and Heroin Abuse in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1789–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1505541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL. Effect of abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:187–189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1204141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. Jama. 2016;315:1624–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deyo RA, Hallvik SE, Hildebran C, et al. Association of Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Use With Opioid Prescribing and Health Outcomes: A Comparison of Program Users and Nonusers. J Pain. 2018.19:166–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Hartung DM, Ahmed SM, Middleton L, et al. Using prescription monitoring program data to characterize out-of-pocket payments for opioid prescriptions in a state Medicaid program. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:1053–1060. doi: 10.1002/pds.4254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1419–1427. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. CDC compilation of benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, stimulants, zolpidem, and opioid analgesics with oral morphine milligram equivalent conversion factors, 2018 version. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/resources/data.html. Accessed 9/10/2020

- 17.Pharmacy Quality Alliance: Opioid Core Measurement Set [online]. Available at: https://www.pqaalliance.org/assets/Measures/PQA_Opioid_Core_Measure_Set_Description.pdf. Accessed Jun 16, 2019.

- 18.Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying Increased Risk of Readmission and In-hospital Mortality Using Hospital Administrative Data: The AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55:698–705. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollini RA, Banta-Green CJ, Cuevas-Mota J, Metzner M, Teshale E, Garfein RS. Problematic use of prescription-type opioids prior to heroin use among young heroin injectors. Subst Abus Rehabil. 2011;2:173–180. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S24800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM. Prescription Opioid Use, Misuse, and Use Disorders in U.S. Adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:293–301. doi: 10.7326/M17-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Alford DP, Argoff C, Canlas B, Covington E, Frank JW et al. Challenges with Implementing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Opioid Guideline: A Consensus Panel Report. Pain Medicine. 2019. Pain Med. 2019;20:724-735. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Dowell D, Haegerich T, Chou R. No Shortcuts to Safer Opioid Prescribing. N Engl J Med 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Fenton JJ, Agnoli AL, Xing G, Hang L, Altan AE, Tancredi DJ, et al. Trends and Rapidity of Dose Tapering Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioid Therapy, 2008-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1916271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Mark TL, Parish W. Opioid medication discontinuation and risk of adverse opioid-related health care events. J Subst Abus Treat. 2019;103:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glanz JM, Binswanger IA, Shetterly SM, Narwaney KJ, Xu S. Association Between Opioid Dose Variability and Opioid Overdose Among Adults Prescribed Long-term Opioid. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e192613–e192613. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliva EM, Bowe T, Manhapra A, Kertesz S, Hah JM, Henderson P, et al. Associations between stopping prescriptions for opioids, length of opioid treatment, and overdose or suicide deaths in US veterans: observational evaluation. BMJ. 2020;368:m283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.James JR, Scott JM, Klein JW, Jackson S, McKinney C, Novack M, et al. Mortality After Discontinuation of Primary Care-Based Chronic Opioid Therapy for Pain: a Retrospective Cohort Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2749–55. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05301-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guy GP, Jr, Zhang K, Schieber LZ, Young R, Dowell D. County-Level Opioid Prescribing in the United States, 2015 and 2017County-Level Opioid Prescribing in the United States, 2015 and 2017Letters. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:574–576. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unick GJ, Ciccarone D. US regional and demographic differences in prescription opioid and heroin-related overdose hospitalizations. The International Journal on Drug Policy 2017;46:112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Guy GP, Pasalic E, Zhang K. Emergency Department Visits Involving Opioid Overdoses, U.S., 2010–2014. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54:e37–e39. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green CA, Perrin NA, Hazlehurst B, et al. Identifying and classifying opioid-related overdoses: A validation study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Buchanich JM, Balmert LC, Williams KE, Burke DS. The Effect of Incomplete Death Certificates on Estimates of Unintentional Opioid-Related Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999-2015. Public Health Rep. 2018;133:423–431. doi: 10.1177/0033354918774330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warner M, Paulozzi LJ, Nolte KB, Davis GG, Nelson LS. State Variation in Certifying Manner of Death and Drugs Involved in Drug Intoxication Deaths. Academic Forensic Pathology. 2013;3:231–237. doi: 10.23907/2013.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlson RG, Nahhas RW, Martins SS, Daniulaityte R. Predictors of transition to heroin use among initially non-opioid dependent illicit pharmaceutical opioid users: A natural history study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:127–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States. CBHSQ Data Review. Published August 2013. Accessed September 10, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 57 kb)