INTRODUCTION

Re-hospitalization of patients receiving post-acute care (PAC) in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) has emerged as a leading health policy issue. PAC is the greatest source of geographic variation in Medicare spending.1 Among hospitalized Medicare fee-for-services beneficiaries, over 20% are discharged to SNFs2 and nearly a quarter of these patients are re-hospitalized.3 SNFs are segregated along racial lines4 and previous research has shown that there are marked racial variations in the odds of re-hospitalization among select surgical patients discharged to these facilities.5 It is not clear how widespread racial disparities in re-hospitalizations among SNF patients are and whether other factors such as Medicaid participation influence the risk of them. We used a national dataset to examine risk-adjusted SNF re-hospitalization rates stratified by the racial composition and the proportion of Medicaid patients in these facilities.

METHODS

We used 2011–2015 data from “Long Term Care: Facts on Care in the US” which include facility-level measures aggregated from the Minimum Data Set (MDS), Medicare Fee-for-Service claims, and the Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting System (now known as CASPER). The data include demographic and clinical characteristics of SNF patients and facility characteristics. 6

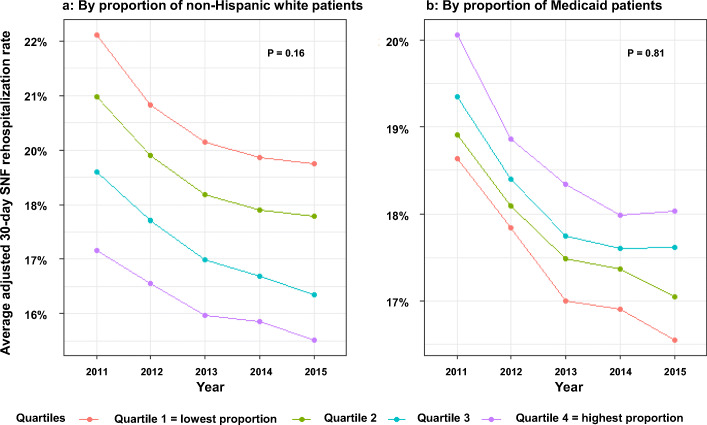

To analyze temporal trends, we stratified the adjusted 30-day SNF re-hospitalization rates by (1) quartiles based on the distribution of the proportions of non-Hispanic white patients and (2) quartiles based on the distribution of the proportion of Medicaid patients, reflecting dual eligibility, where the first quartile represents the lowest percentages and the fourth quartile the highest percentages. The re-hospitalization rate was adjusted for patient demographics, functional status, prognosis, clinical conditions, diagnoses, and services received.6 Trends were analyzed by comparing differences in re-hospitalization rates between the first and fourth quartiles over time using linear regression. Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 3.5.3.

RESULTS

Changes in patient and facility characteristics were observed over the study period (Table 1). The total number of SNFs declined from 15,564 in 2011 to 15,282 in 2015 (− 1.8%, P = 0.04). Total SNF beds declined by 1.2% (P = 0.10) and the proportion of hospital-based SNFs declined from 6.1 to 5.2% (P = 0.37). The mean proportion of white patients declined by 1.7% (P < 0.001), and patients under age 65 increased by 2.3% (P < 0.001). The median proportion of Medicare beneficiaries and Medicaid patients declined by 5.0% (P = 0.01) and 2.0% (P = 0.02), respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of US Skilled Nursing Facilities and patients 2011–2015

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | P value for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNF | ||||||

| Number | 15,564 | 15,551 | 15,515 | 15,383 | 15,282 | 0.04 |

| Beds per SNF, mean (SD) | 107 (62) | 107 (62) | 107 (62) | 107 (62) | 107 (62) | 0.37 |

| Total SNF beds | 1,545,696 | 1,544,823 | 1,543,170 | 1,534,724 | 1,526,993 | < 0.001 |

| For-profit SNFs, % | 69.2 | 69.1 | 69.6 | 69.9 | 69.3 | 0.76 |

| Multi-facility SNFs, % | 54.9 | 54.7 | 55.2 | 56.0 | 56.8 | 0.01 |

| Hospital-based SNFs, % | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 0.02 |

| SNF patient characteristics, % | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white, mean (SD) | 82.4 (21.5) | 82.1 (21.5) | 82.0 (21.4) | 81.3 (21.5) | 81.0 (21.6) | < 0.001 |

| Female, mean (SD) | 69.2 (12) | 68.8 (12) | 68.2 (12) | 67.7 (12) | 67.1 (12) | < 0.001 |

| Under 65, mean (SD) | 21.7 (19.7) | 21.8 (19.5) | 21.9 (19.3) | 22.1 (18.9) | 22.2 (18.6) | < 0.001 |

| Ventilator support, mean (SD) | 34.2 | 31.9 | 35.2 | 35.9 | 37.8 | 0.01 |

| Medicare, mean (SD) | 15.8 (15.9) | 15.6 (15.7) | 15.6 (15.5) | 15.1 (14.8) | 14.3 (14.2) | 0.01 |

| Medicaid, mean (SD) | 60.2 (23.3) | 60.2 (23.2) | 59.8 (23.3) | 59.6 (23.2) | 59.1 (23.3) | 0.02 |

Downward trends in SNF 30-day re-hospitalization rates were observed for all quartiles based on the percentages of non-white patients and Medicaid patients (Fig. 1). However, these trends were not statistically significant (P = 0.16 for percent white; P = 0.81 for percent Medicaid). Thus, while overall 30-day SNF re-hospitalization rates have declined since 2011 (P = 0.02), differences in these rates have not narrowed between SNFs with high and low proportions of non-white patients or with high and low proportions of Medicaid patients.

Figure 1.

Trends in average adjusted 30-day skilled nursing facility re-hospitalization ratesϮ by the proportion of white patients and the proportion of Medicaid patients. ϮAdjusted SNF 30-day re-hospitalization rates calculated as a SNF’s actual re-hospitalization rate divided by expected re-hospitalization rate multiplied by the national average, where the expected re-hospitalization rate is adjusted in a multi-variate logistic model using 33 demographic and clinical covariates taken from Minimum Data Set assessments: age > 65 years, male, Medicare payer, total bowel incontinence, eating dependence, need for 2 person assist, cognitive impairment, hospice care, history of respiratory failure, recent re-hospitalization, poor end stage prognosis, presence of daily pain, ulcers, diagnoses of anemia, diabetes, heart failure, history of sepsis, hepatitis or internal bleeding; services received including dialysis, insulin, ostomy care, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, intravenous medication, oxygen, or tracheostomy care.

DISCUSSION

We found an overall decline in SNF re-hospitalization rates over the period 2011 to 2015. However, when stratified by patients’ race and Medicaid coverage, differences between top and bottom quartiles did not narrow over time.

Although there were overall declines in SNF re-hospitalization rates, our findings suggest persistent disparities associated with race and Medicaid participation. This has important policy implications because financial penalties assessed through the SNF Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program are based solely on re-hospitalization rates, suggesting that SNFs with disproportionate shares of non-white and Medicaid patients may face larger penalties as an unintended consequence.

Important limitations of our study include the use of administrative data with a cross-sectional study design. It is possible that unobserved patient characteristics may have biased estimates. Future studies should examine the impact of penalties from the SNF VBP on disparities in SNF re-hospitalization rates by racial and Medicaid composition.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Ghosh is supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant KL2-TR-002385 of the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Dr. Jung is the recipient of a Mentored Research Scientist Development Award from the National Institute on Aging (K01AG057824).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Newhouse JP, Garber AM, Graham RP, McCoy MA, Mancher M, Kibria A. Variation in Health Care Spending: Target Decision Making, Not Geography. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in Post-Acute Care Use Among Medicare Beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319:1616–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2010;29:57–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno JM, Miller SC. Driven to tiers: socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. The Milbank quarterly. 2004;82:227–56. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang M, Hume E, Ibrahim S. Race, Bundled Payment Policy, and Discharge Destination After TKA: The Experience of an Urban Academic Hospital. Geriatric orthopaedic surgery & rehabilitation. 2018;9:2151459318803222. doi: 10.1177/2151459318803222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LTCfocus Brown University. (Accessed September 12th 2019, at http://ltcfocus.org/.)