Abstract

Significance

Guidelines urge primary care practices to routinely provide tobacco cessation care (i.e., assess tobacco use, provide brief cessation advice, and refer to cessation support). This study evaluates the impact of a systems-based strategy to provide tobacco cessation care in eight primary care clinics serving low-income patients.

Methods

A non-randomized stepped wedge study design was used to implement an intervention consisting of (1) changes to the electronic health record (EHR) referral functionality and (2) expansion of staff roles to provide brief advice to quit; assess readiness to quit; offer a referral to tobacco cessation counseling; and sign the referral order. Outcomes assessed from the EHR include performance of tobacco cessation care tasks, referral contact, and enrollment rates for the quitline (QL) and in-house Freedom from Smoking (FFS) program. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) methods were used to compute odds ratios contrasting the pre-implementation vs. 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month post-implementation periods.

Results

Of the 176,061 visits, 26.1% were by identified tobacco users. All indicators significantly increased at each time period evaluated post-implementation. In comparison with the pre-intervention period, assessing smoking status (26.6% vs. 55.7%; OR = 3.7, CI = 3.6–3.9), providing advice (44.8% vs. 88.7%; OR = 7.8, CI = 6.6–9.1), assessing readiness to quit (15.8% vs. 55.0%; OR = 6.2, CI = 5.4–7.0), and acceptance of a referral to tobacco cessation counseling (0.5% vs. 30.9%; OR = 81.0, CI = 11.4–575.8) remained significantly higher 12 months post-intervention. For the QL and FFS, respectively, there were 1223 and 532 referrals; 324 (31.1%) and 103 (24.7%) were contacted; 241 (74.4%) and 72 (69.6%) enrolled; and 195 (80.9%) and 14 (19.4%) received at least one counseling session.

Conclusions

This system change intervention that includes an EHR-supported role expansion substantially increased the provision of tobacco cessation care and improvements were sustained beyond 1 year. This approach has the potential to greatly increase the number of individuals referred for tobacco cessation counseling.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-020-06030-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: tobacco cessation, primary care, community linkages, EHR, quitline

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the USA, killing more than 480,000 people each year.1 Smoking prevalence is higher among the socioeconomically disadvantaged, who are also less likely to successfully quit.2, 3 Telephone-based counseling for smoking cessation, or quitline (QL) counseling, is an effective, evidence-based treatment recommended by clinical guidelines.4–6 Quitlines offer free access to smoking cessation support for those interested in quitting and have the potential to reach a large segment of the population and reduce tobacco disparities.7 However, additional efforts are needed to increase the reach and impact of QL treatment in low-income populations.

Primary care providers (PCPs) are in a unique position to facilitate tobacco cessation, as 59% of US tobacco users report seeing a PCP at least once per year.8 Health system change interventions for tobacco cessation are recommended9 and have the potential to improve the provision of tobacco cessation support by integrating the identification of all tobacco users and the offering of cessation support into the routine delivery of care.10 Proactive clinical referrals to QLs, in which a PCP directly sends a referral to the QL, which then prompts the QL to call the patient, have shown promising enrollment rates.11, 12 Clinician implementation of this strategy has been low however,13 and clinicians and practices need additional help to take advantage of the opportunity to provide cessation assistance to patients who smoke.

System change interventions have the potential to address the systemic barriers within health systems by efficiently incorporating health information technology, engaging clinical support staff, and not adding significant time to clinical visits.14 Implementation strategies that engage multiple levels of leadership, build capacity through staff training, and effectively integrate documentation into new workflows are important for supporting the sustainability of the system change.15 The current study evaluates an approach to design and implement a sustainable, systems-based strategy to provide tobacco cessation care in eight primary care clinics serving low-income patients.

METHODS

Overview

This study represents an evaluation of a systems change intervention implemented in eight community-based Ohio primary care clinics within a health system and examines data from 3 months prior to the intervention to 12 months after the intervention. The intervention was modeled in part on an Ask-Advise-Connect (AAC) approach to tobacco cessation care,16, 17 and hereafter, we refer to the intervention as AAC. We use a non-randomized stepped wedge design with eight sites and roll out at 1-month intervals to evaluate the effect of the AAC intervention on the following: (1) processes variables including documentation of assessing tobacco use status, providing brief advice to quit, assessing readiness to quit, and patient acceptance of an offer to refer to tobacco cessation assistance; (2) patient contact and enrollment in a cessation assistance program (either the QL telephone counseling or the in-house Freedom from Smoking (FFS) group class.)

Intervention Design

The development of the intervention and implementation strategy, including the research team—healthcare organization co-design of the approach, is reported elsewhere.18 Briefly, in preparation for this study, the capacity to send an electronic referral from the Epic electronic health record (EHR) system to the state’s QL provider was established with a real-time, closed-loop referral such that data about the disposition of the referral (e.g., contact, enrollment, the number of counseling sessions received) are provided through a secure exchange and become part of the patient’s EHR record. Prior to the start of this study, medical assistants and nurses (MA/RNs), the clinic staff who room patients and assess vital signs before the patient is seen by their clinician, were responsible for assessing and documenting smoking status. With the intervention, their role expanded to the following: (1) advising those who use tobacco to quit using a brief scripted phrase; (2) asking tobacco users if they were interested in quitting in the next 30 days; (3) asking those who indicated that they were interested in quitting now if they would like assistance to quit from a coach or counselor; and (4) if the patient wanted assistance with quitting, ordering a referral for assistance that was electronically sent to either the QL or to the FFS program. (See the Appendix Table 4 for change in EHR functionality and role expectations.) Eligibility for free QL services included being aged 18 or older with Medicaid insurance or no insurance or being pregnant. The QL included up to 5 telephonic counseling sessions and access to web and online chat support. Individuals that were not eligible for the QL were referred to the in-system FFS program—an in-person 8-session group tobacco cessation class offered by the healthcare system. The EHR automatically generated the correct referral order using patient payer data. Therefore, regardless of eligibility, the process was seamless for both the MA/RN and the patient.

Intervention Implementation

The MA/RN training included a presentation about the goal of the project, a detailed description of the new features in the EHR and the eReferral capacity, a description of the new role/steps for accomplishing the AAC tasks, and an opportunity to ask questions. Support materials, including a tip sheet detailing how to use the new EHR sections and the overall AAC process, were developed with the assistance of local Epic EHR trainers to match the standard format and style of documents used by the health system for implementation of other EHR changes. Following the 30-min presentation, a 30-min hands-on session allowed MA/RNs to try the process and new EHR features with fictional test patients. The study team addressed questions that staff raised as they interacted with the new EHR sections. The EHR capacity to provide an eReferral was enabled at each clinic on the day of the intervention training. The training and implementation approach were the same for each site.

Beginning approximately 1 month after implementation, a performance feedback report showing data at the site level, and aggregate data from the 7 other participating sites, was shared with the practice manager of each site. The data were presented numerically and graphically. This report was generated and shared every 2 months for the 6 months following implementation. We allowed practice managers to share and discuss the report information with staff in whatever way they chose (e.g., at staff meetings or monthly quality improvement meetings).

Participants

All 81 MA/RNs at the eight clinics who were involved in routinely rooming patients and assessing vital signs participated in the study. All patients 18 and older seen by participating MA/RNs during the observation period at the eight clinics were eligible for tobacco assessment as part of routine clinical care.

Measures

Patient characteristics including age, gender, race, ethnicity, and insurance type were assessed from the EHR. The main variables for this study include the process variables of asking about tobacco status, providing advice, assessing readiness to quit, patient acceptance of a referral to the QL or FFS for tobacco cessation support, and connection to the QL or FFS. EHR data were used to assess these variables for both the pre- and post-implementation periods. Because eReferrals to the QL were not able to be documented prior to the implementation of the study, referrals to the in-house FFS program were used as the estimate of baseline tobacco cessation referrals. Referral outcome data from the QL and FFS included whether the referred individual was contacted and enrolled in the program and, if enrolled, the number of counseling sessions received. Data collection took place from December 2017 to December 2018. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the MetroHealth System.

Analyses

We describe the patient samples in the baseline and post-intervention periods. Process variables are reported by time period. Using the 3 months prior to implementation as the reference, generalized estimating equations (GEE) models estimated odds ratios describing the intervention’s effect for each process indicator for 1, 3, 6 and 12 months post-intervention, adjusting for clustering of visits within clinic sites and for the timing of each clinic’s transition from pre-implementation to post-implementation per the study design. Process variable performance is graphically displayed for each of the five time points and eight intervention sites.

GEE models also examined the effect of the AAC implementation contact by the FFS or QL and FFS or QL enrollment. These analyses examine pre- vs post-AAC implementation and adjust for the time that the site entered the active intervention period and for clustering of visits within the site. Finally, we examined the heterogeneity of intervention effect for sex, age, race, ethnicity, and insurance type using a characteristic × time period interaction.

RESULTS

Among the 176,061 patient visits for the pre- and post-intervention periods, 26.1% were identified as tobacco users. Patient characteristics for the two time periods are shown in Table 1 and there are no substantial differences in patient characteristics between the two periods. Table 2 shows the uptake in the key process variables for the 3 months before implementing the AAC strategy and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after AAC implementation. The pre-implementation period serves as the baseline group and, as shown in Table 2, the intervention had a 2-fold increase in asking about tobacco use status across the eight sites at the 1-month post-intervention time point. This level of impact increased at each of the subsequent time points and OR = 3.72 (95% CI 3.56–3.89) at 12 months post-implementation.

Table 1.

Characteristics for Pre-AAC and Post-AAC Implementation Groups

| Description | Category | Overall, 176,061 (100.0%) | Pre-AAC Implementation, 36,677 (20.8%) | Post-AAC Implementation, 139,384 (79.2%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 53,518 (30.4%) | 11,338 (30.9%) | 42,180 (30.3%) |

| Female | 122,542 (69.6%) | 25,338 (69.1%) | 97,204 (69.7%) | |

| Age in years | 18–34 | 43,804 (24.9%) | 9099 (24.8%) | 34,705 (24.9%) |

| 35–64 | 100,851 (57.3%) | 21,400 (58.3%) | 79,451 (57.0%) | |

| 65+ | 31,406 (17.8%) | 6178 (16.8%) | 25,228 (18.1%) | |

| Race | White | 79,138 (50.0%) | 15,867 (48.0%) | 63,271 (50.5%) |

| African American | 73,320 (46.3%) | 16,048 (48.6%) | 57,272 (45.7%) | |

| Other | 5802 (3.7%) | 1108 (3.4%) | 4694 (3.7%) | |

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | 150,782 (87.9%) | 31,531 (88.2%) | 119,251 (87.8%) |

| Hispanic | 20,840 (12.1%) | 4209 (11.8%) | 16,631 (12.2%) | |

| Primary insurance class | Commercial | 51,484 (29.9%) | 10,470 (29.5%) | 41,014 (30.1%) |

| Medicaid | 68,714 (40.0%) | 14,736 (41.5%) | 53,978 (39.6%) | |

| Medicare | 41,014 (23.9%) | 8285 (23.3%) | 32,729 (24.0%) | |

| Self-pay | 10,540 (6.1%) | 1979 (5.6%) | 8561 (6.3%) | |

| Other | 206 (0.1%) | 34 (0.1%) | 172 (0.1%) | |

| Smoking status | Current tobacco user | 37,909 (26.1%) | 8167 (26.7%) | 29,742 (25.9%) |

| Former tobacco user | 40,732 (28.0%) | 8525 (27.8%) | 32,207 (28.0%) | |

| Never smoked | 66,873 (45.9%) | 13,953 (45.5%) | 52,920 (44.3%) | |

| Not assessed* | 30,547 (17.4%) | 6032 (16.4%) | 24,515 (17.6%) | |

| MH health center | A | 14,299 (8.1%) | 3003 (8.2%) | 11,296 (8.1%) |

| B | 31,704 (18.0%) | 5899 (16.1%) | 25,805 (18.5%) | |

| C | 22,053 (12.5%) | 3727 (10.2%) | 18,326 (13.1%) | |

| D | 21,348 (12.1%) | 4521 (12.3%) | 16,827 (12.1%) | |

| E | 5434 (3.1%) | 2573 (7.0%) | 2861 (2.1%) | |

| F | 21,757 (12.4%) | 4680 (12.8%) | 17,077 (12.3%) | |

| G | 33,526 (19.0%) | 6862 (18.7%) | 26,664 (19.1%) | |

| H | 20,587 (11.7%) | 4399 (12.0%) | 16,188 (11.6%) | |

| I | 5353 (3.0%) | 1013 (2.8%) | 4340 (3.1%) |

*Not included in the denominator for smoking status

Table 2.

Tobacco Assistance and Referral Outcomes by Ask-Advice-Connect (AAC) Implementation Period for Eight Sites

| 1–3 months before AAC | 1 month after AAC | 3 months after AAC | 6 months after AAC | 12 months after AAC | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | OR (95% CI) | N | % | OR* (95% CI) | N | % | OR (95% CI) | N | % | OR (95% CI) | N | % | OR (95% CI) | |

| Total visits | 36,677 | 12,274 | 12,012 | 11,605 | 11,991 | ||||||||||

| % asked | 9742 | 26.6% | ---- | 5035 | 41.0% | 1.93 (1.85, 2.00) | 5437 | 45.3 | 2.33 (2.24, 2.43) | 5976 | 51.5 | 3.08 (2.95, 3.22) | 6674 | 55.7% | 3.72 (3.56, 3.89) |

| Visits by smoker | 2775 | 1729 | 1890 | 1891 | 2117 | ||||||||||

| % advised | 1243 | 44.8% | ---- | 1430 | 82.7% | 4.71 (4.06, 5.48) | 1490 | 78.8 | 3.72 (3.23,4.28) | 1589 | 84.0 | 5.16 (4.44, 6.00) | 1877 | 88.7 | 7.76 (6.61, 9.12) |

| % assess readiness | 438 | 15.8% | ---- | 1283 | 74.2% | 14.90 (12.80, 17.33) | 1244 | 65.8 | 9.87 (8.56, 11.39) | 1225 | 64.8 | 9.29 (8.08, 10.69) | 1164 | 55.0% | 6.15 (5.37, 7.03) |

| Visits by smoker ready to quit in 30 days | 184 | 484 | 437 | 399 | 301 | ||||||||||

| % accepted referral | 1 | 0.5% | ---- | 285 | 58.9% | 260.51 (36.87, 1840.52) | 245 | 56.1 | 230.97 (32.66, 1633.34) | 151 | 37.8 | 110.17 (15.55, 780.34) | 93 | 30.9% | 80.95 (11.38, 575.80) |

*All OR are in contrast to 1–3 months before AAC implementation

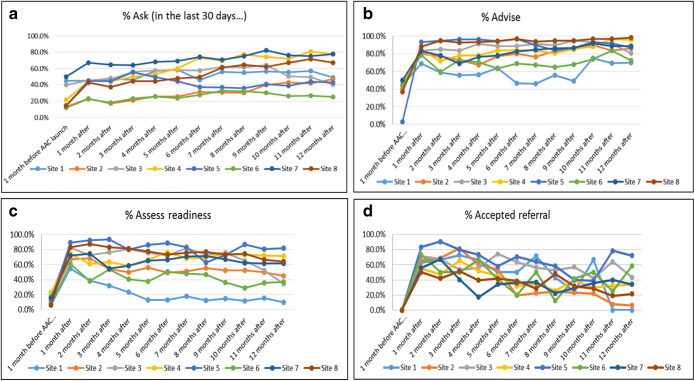

Provision of a brief advice statement to quit smoking increased more than 4-fold (OR = 4.71 (95%CI 4.06–5.48)) 1 month after the implementation of the AAC intervention. Performance rates increased from 44.8% at baseline to 82.7% and with the exception of the 3-month post-implementation time point (78.8%), maintained performance above 80%. For assessing readiness, the baseline rate of 15.8% increased to 74.2% 1 month after AAC implementation (OR = 14.90 (95% CI 12.80–17.33)). The rate at the 12-month follow-up period was 55% (OR 6.15 (95% CI 5.37–7.03)). All patients documented as ready to quit in the next 30 days were offered a referral to tobacco cessation counseling (i.e., QL or FFS). We report on patient acceptance of that referral. Compared with baseline, acceptance of referral increases dramatically post-implementation and then gradually decreases over the 12-month follow-up period. The pre-AAC acceptance rate of referrals was 0.5% (1 person) and 1-month post AAC implementation was 58.9% (OR = 260.51 (38.87–1840.52)). By 12 months post AAC, the rate had decayed to 30.9% which is still considerably higher than the pre-AAC period (OR = 80.95 (95% CI 11.38–575.80)). Figure 1 panels a–d show the effect of the intervention at each of the eight clinical sites. Six sites improved and generally maintained their improvement, while two made only marginal improvements and then declined back to baseline.

Figure 1.

a–d Performance of ask, advise, assess readiness, and patient acceptance of a referral for 8 sites for 12 months post-implementation.

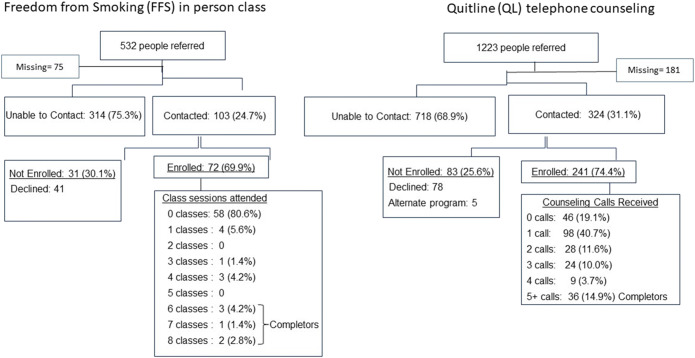

Among the 532 individuals referred to the FFS program, 417 had outcome data. A total of 103 (25%) were contacted by the program, 72 (70%) enrolled and only 14 (19%) attended 1 or more classes. (See Fig. 2.) Among 1223 patients referred to the QL, 30% were contacted by the QL; of those contacted, 74.4% enrolled and 80.7% of those enrolled received 1 or more counseling calls. However, 99 (40.6%) of those that enrolled received only 1 of the recommended 5 counseling calls before disenrolling or becoming unreachable by the QL.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of referrals and enrollment for Freedom from Smoking and the quitline.

Finally, we assess the heterogeneity of the AAC intervention effect across subgroups for each of the process indicators. As shown in Table 3, the percent of visits for males where ASK was documented was 23% pre-implementation and this increased to 53% after the AAC implementation, whereas the documentation of ASK at visits for females was 27% and 50% after the AAC implementation. The sex × time period interaction was significant (p < .001) which indicates that the intervention had a greater positive impact on documentation of smoking status for visits by male patients vs. female patients. For ASK, each of the characteristics examined resulted in a statistically significant interaction effect. We interpret an observed 10% difference in changes as clinically meaningful. With these criteria, one variable, “other race” showed a much smaller increase in ASK than did whites and African Americans (12.0 vs. 24.2 and 27.9, respectively).

Table 3.

Tobacco Assessment and Assistance by Time Period and Test of Heterogeneity of Effect for Sex, Age, Race, Ethnicity, and Insurance Type

| Description | Category | Pre-AAC implementation, n = 36,676 | Post-AAC implementation, n = 139,384 | Pre-post-AAC difference | Significant interaction effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||||

| ASK∞, % yes | |||||

| Gender | Male | 24.1 | 52.6 | 28.5 | ** |

| Female | 27.6 | 49.9 | 22.3 | ||

| Age in years | 18–34 | 22.6 | 43.1 | 20.5 | |

| 35–64 | 27.8 | 53.1 | 26.0 | ||

| 65+ | 27.9 | 53.7 | 25.8 | ||

| Race | White | 33.4 | 56.5 | 23.1 | *** |

| Black | 21.6 | 48.7 | 27.1 | ||

| Other | 22.3 | 34.2 | 11.9 | ||

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | 27.7 | 52.7 | 25.0 | |

| Hispanic | 18.4 | 35.9 | 17.5 | ||

| Primary insurance class | Commercial | 29.8 | 52.2 | 22.4 | ** |

| Medicaid/self-pay | 23.5 | 47.6 | 24.1 | ||

| Medicare | 28.6 | 55.2 | 26.6 | ||

| ADVISE, % yes | |||||

| Gender | Male | 22.2 | 40.9 | 18.7 | |

| Female | 12.9 | 30.4 | 17.5 | ||

| Age in years | 18–34 | 15.3 | 30.3 | 15.0 | |

| 35–64 | 17.4 | 38.3 | 20.9 | ||

| 65+ | 9.4 | 23.1 | 13.7 | ||

| Race | White | 16.1 | 36.2 | 20.1 | |

| African American | 16.3 | 32.9 | 16.6 | ||

| Other | 5.7 | 21.4 | 15.7 | ||

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | 15.8 | 34.7 | 18.9 | |

| Hispanic | 11.8 | 22.7 | 10.9 | ||

| Primary insurance class | Commercial | 12.2 | 28.1 | 15.9 | |

| Medicaid/self-pay | 20.7 | 41.1 | 20.4 | ||

| Medicare | 12.5 | 29.8 | 17.3 | ||

| Assess readiness, % yes | |||||

| Gender | Male | 6.4 | 26.8 | 20.4 | |

| Female | 4.2 | 18.7 | 14.5 | ||

| Age in years | 18–34 | 4.8 | 17.5 | 12.7 | |

| 35–64 | 5.5 | 25.4 | 19.9 | ||

| 65+ | 2.4 | 12.5 | 10.1 | ||

| Race | White | 4.4 | 21.1 | 16.7 | |

| African American | 5.9 | 23.5 | 17.6 | ||

| Other | 1.2 | 7.7 | 6.5 | ||

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | 5.1 | 22.0 | 16.9 | |

| Hispanic | 2.6 | 13.7 | 11.1 | ||

| Primary insurance class | Commercial | 2.7 | 15.3 | 12.6 | |

| Medicaid/self-pay | 7.3 | 28.3 | 21.0 | ||

| Medicare | 4.2 | 18.2 | 14.0 | ||

| Accept connect, % yes | |||||

| Gender | Male | 0 | 43.7 | 43.7 | |

| Female | 0.8 | 43.6 | 42.8 | ||

| Age in years | 18–34 | 0 | 41.5 | 41.5 | |

| 35–64 | 0 | 44.6 | 44.6 | ||

| 65+ | 12.5 | 40.0 | 27.5 | ||

| Race | White | 0 | 40.4 | 40.4 | |

| African American | 0.7 | 45.8 | 45.1 | ||

| Other | 0 | 48.1 | 48.1 | ||

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | 0.6 | 42.9 | 42.3 | |

| Hispanic | 0 | 52.0 | 52.0 | ||

| Primary insurance class | Commercial | 0 | 41.8 | 41.8 | |

| Medicaid/self-pay | 0 | 44.1 | 44.1 | ||

| Medicare | 3.0 | 42.9 | 39.9 | ||

∞analyses for ASK include smoking status as a covariate

**indicates significant interaction effect p < 0.001

***indicates significant interaction effect p < 0.001 and greater than 10 difference in the proportion

DISCUSSION

This health systems change intervention increased the provision of tobacco cessation care, and these improvements were sustained over 12 months. Several implementation strategies likely contributed to the success of this intervention. The most robust uptake and sustained performance were for the provision of brief advice to quit smoking, which may be a result of the study team extensively engaging MA/RNs as the frontline users of the approach during the development of the wording and the implementation phase.18 This engagement resulted in a phrase that they were comfortable using during routine care. It was also likely motivating and empowering for MA/RNs to sign the referral order for external tobacco cessation counseling15 which, at the time of this study, was the only referral order that MA/RNs had permissions to place and sign. Other essential steps were engaging practice managers in-person at each of the eight sites to prepare for the training sessions and scheduling the training during routine monthly staff meetings. This facilitated attendance and minimized workflow interruption. Finally, receiving approval from healthcare system leadership, specifically from population health and primary care leaders, signaled the importance of the study to the frontline staff and increased staff buy-in at each of the practices. The approach could be sustained beyond the research project because the process was entirely up to the clinical staff.

The pre- and post-implementation performance of ASK is of interest for several reasons. As the only tobacco assessment indicator that was in place as part of the MA/RN role prior to this project, the pre-implementation rate (26%) appears low. Also, although Ask continued to improve over the 12-month post-implementation period, it remained relatively low, with just over half of the visits with ASK documented. Although this health system implemented a policy of asking smoking status for “every patient at every visit,” others and especially MA/RNs may find that policy uncomfortable or impractical. However, research indicates that health providers’ concerns of alienating tobacco users by offering cessation advice and assistance are unsupported.19, 20 Patients who use tobacco expect and value their providers’ regular assessment of tobacco use status,21 and satisfaction with care is highest among tobacco users who receive cessation assistance or follow-up.19, 22 Informing healthcare teams of these findings from patient reports may help to alleviate concerns about assessing tobacco use status for every patient at every visit.

Importantly, our analyses found that the improvements observed for the tobacco assistance indicators resulted in improvements across all subgroups studied including age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance type. Performance improved equally for all subgroups with the exception of ASK being performed less frequently for other race vs. whites and blacks. One possible explanation is that language limitations, e.g., patients for whom English was a second language or non-English speakers, may have presented challenges to MA/RNs for assessing behaviors like tobacco use status. While translation services are generally available, assuring that they are present for the check-in phase of the visit when the tobacco assessment occurs may help close this gap.

Among those for whom a referral order for tobacco cessation counseling was placed, the contact rate was 24% for FFS and 30% for the QL. These contact rates are similar to those reported in other studies.17 Few have identified reasons for not being able to contact individuals referred for tobacco cessation which include minimal knowledge about services provided by quitlines.21, 23 Others have found concerns about talking with a stranger over the phone and lack of trust especially about providing personal information over the phone among low-income populations.24 Identifying ways to reduce these barriers is important because connecting individuals with assistance in a timely manner when they have expressed an interest in quitting can increase the engagement in receiving support to do so.

In this study, among those who were contacted, the enrollment rate was 69% and 74% for FFS and QL, respectively. Few other studies report enrollment rates.17, 25 In our study, we see a substantial divergence in receipt of counseling for the two services available. First, the in-person class had a very poor attendance rate—17% of those enrolled attended one or more counseling sessions. This may be due to barriers of transportation, child care, or the elapsed time from the referral to the opportunity to attend a class. Because of limited resources to offer the class, there could be a wait of eight or more weeks to get into the next class offered. For those enrolled in QL telephone counseling, 80.7% received at least one counseling session. However, one call was the mode with 40.6% of enrolled individuals receiving only one QL counseling session before disenrolling or becoming unreachable for subsequent counseling sessions. Others have reported similar engagement and retention challenges.26, 27 Prioritizing tobacco cessation counseling calls among busy, stressful, and sometimes chaotic life events can be difficult even for those who strongly express the desire to get cessation assistance.21 Improving the contact and enrollment of individuals is important for the sustainability of strategies that rely on a referral to cessation support outside of the visit. Future research should also investigate alternative and/or additional referral options, particularly to serve disadvantaged populations.24, 28 Strategies that follow up with individuals who expressed interest in assistance, but who did not connect with the referral organization, may increase engagement in tobacco cessation support and sustain the patient-clinic relationship.

The approach to training and technical assistance to implement the AAC strategy had good fidelity across each of the eight community health centers. The implementation process, trainers, and materials were the same for each of the practices. Similar to other studies,29 however, there was variation in the uptake of assessing readiness and therefore offering referral to the QL across the eight health centers. While beyond the scope of this paper, the examination of practice features associated with uptake of the processes is important to understand how to improve the implementation approach. For systems to benefit long term from consistent use of tools like AAC, more research is needed to understand the impact of implementation supports such as ongoing training for new employees and providing feedback about performance and patient outcomes to staff.

Limitations

This study was conducted in one healthcare system that serves a predominately low-income patient population with a 26% patient tobacco use rate. The observed effects of the intervention on tobacco cessation support and patient engagement in tobacco cessation assistance may not generalize to other settings with different characteristics. The baseline performance of advise, assess, and refer/connect is likely to be exclusively performed by clinicians. The observed changes between baseline and subsequent follow-up points are attributed to our intervention, but it is possible that some of the increase could have been due to clinicians. However, there was no systematic intervention provided to clinicians during this study period. Pharmacotherapy is an important part of supporting tobacco cessation; no information on use of cessation pharmacotherapy was assessed. Finally, it was necessary to rely on documentation of referral to FFS as the estimate of assistance offered in the pre-implementation period because documentation of eReferrals to the QL was available prior to the implementation of the study. With only one documented person accepting a referral to the FFS program in the pre-implementation period, interpretation of the OR for the intervention effect for comparator time periods should be done with caution.

CONCLUSIONS

A systems change intervention that includes an EHR-supported role expansion for the clinical support staff can substantially increase the provision of tobacco cessation support; however, there is considerable room for improving enrollment and completion of cessation programs. The sustained performance observed in this study is likely due to the implementation strategy designed in partnership with health system leadership, and with representation and real input from frontline staff to ensure thoughtful integration into the workflow. Furthermore, since the AAC process documentation is embedded in the EHR, the healthcare system has practical functionality for ongoing monitoring of the process to sustain and increase improvements.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 12 kb)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Elvira Ordillas, RN, Georgene Bosich, RN, Jay Koren, RN, Teodoro Rosati, and Versie Owens, MPA, who contributed to making this project possible.

Funding Information

The research reported in this manuscript was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI ®) Award (IHS-1503-29879). The statements presented in this work are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI ®), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the MetroHealth System.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.U S Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA; 2014. NBK179276

- 2.Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler JA, Munafò M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1248:107–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, et al. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(2):53–59. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6702a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaza S, Lawrence RS, Mahan CS, et al. Scope and organization of the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1S):27–34. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Stead LF, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8(8):CD002850. 10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Fiore M, Jaen C, Baker T, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu SS, van Ryn M, Nelson D, et al. Proactive tobacco treatment offering free nicotine replacement therapy and telephone counselling for socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers: a randomised clinical trial. Thorax. 2016;71(5):446–453. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey, 2011 Data Release. ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Datasets/NHIS/2011/samadult.zip. Published 2012.

- 9.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TR, et al. A Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 update. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:158–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas D, Mj A, Bonevski B, George J. System change interventions for smoking cessation ( Review ). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;(2). 10.1002/14651858.CD010742.pub2.www.cochranelibrary.com [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Rothemich SF, Woolf SH, Johnson RE, et al. Promoting Primary Care Smoking-Cessation Support with Quitlines. The QuitLink Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warner DD, Land TG, Rodgers AB, Keithly L. Integrating tobacco cessation quitlines into health care: Massachusetts, 2002-2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E133. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathew M, Goldstein AO, Kramer KD, Ripley-Moffitt C, Mage C. Evaluation of a direct mailing campaign to increase physician awareness and utilization of a quitline fax referral service. J Health Commun. 2010;15(8):840–845. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rojewski AM, Bailey SR, Bernstein SL, et al. Considering Systemic Barriers to Treating Tobacco Use in Clinical Settings in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;(July):1-9. 10.1093/ntr/nty123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Whittet M, Capesius T, Zook H, Keller P. The Role of Health Systems in Reducing Tobacco Dependence. Am J Accountable Care. 2019;7(2):4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vidrine JI, Shete S, Cao Y, et al. Ask-Advise-Connect A New Approach to Smoking Treatment Delivery in Health Care Settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):458–464. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vidrine JI, Shete S, Li Y, et al. The ask-advise-connect approach for smokers in a safety net healthcare system: A group-randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(6):737–741. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flocke S, Seeholzer E, Lewis S, et al. Designing for sustainability: an approach to integrating staff role changes and electronic health record functionality within safety-net clinics to address provision of tobacco cessation care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2019;In Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Quinn VP, Stevens VJ, Hollis JF, et al. Tobacco-cessation services and patient satisfaction in nine nonprofit HMOs. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halladay JR, Vu M, Ripley-moffitt C, Gupta SK, Meara CO, Goldstein AO. Patient Perspectives on Tobacco Use Treatment in Primary Care. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12(E14):1–8. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albert EL, Rose JC, Gill IJ, Flocke SA. Patient experience of electronic referrals to quitlines. Health Educ Behav. 2019;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Conroy MB, Majchrzak NE, Regan S, Silverman CB, Schneider LI, Rigotti NA. The association between patient-reported receipt of tobacco intervention at a primary care visit and smokers’ satisfaction with their health care. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1(Suppl_1)):S29–34. doi: 10.1080/14622200500078063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters EA, McQueen A, Caburnay CA, et al. Perceptions of the US National Tobacco Quitline among adolescents and adults: A qualitative study, 2012-2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12(8). 10.5888/pcd12.150139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Sheffer C, Brackman S, Lercara C, et al. When free is not for me: Confronting the barriers to use of free quitline telephone counseling for tobacco dependence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;13(1). 10.3390/ijerph13010015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Piñeiro B, Wetter DW, Vidrine DJ, et al. Quitline treatment dose predicts cessation outcomes among safety net patients linked with treatment via Ask-Advise-Connect. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13(April 2018):262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burns EK, Levinson AH, Deaton EA. Factors in Nonadherence to Quitline Services: Smoker Characteristics Explain Little. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39(5):596–602. doi: 10.1177/1090198111425186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lien RK, Schillo BA, Mast JL, et al. Tobacco User Characteristics and Outcomes Related to Intensity of Quitline Program Use: Results From Minnesota and Pennsylvania. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(5):36–46. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McQueen A, Roberts C, Garg R, et al. Specialized tobacco quitline and basic needs navigation interventions to increase cessation among low income smokers: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;80(December 2018):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarthy DE, Adsit RT, Zehner ME, et al. Closed-loop electronic referral to SmokefreeTXT for smoking cessation support: a demonstration project in outpatient care. Transl Behav Med. 2019. 10.1093/tbm/ibz072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 12 kb)