Abstract

Background

Identifying characteristics of primary care practices that perform well on cardiovascular clinical quality measures (CQMs) may point to important practice improvement strategies.

Objective

To identify practice characteristics associated with high performance on four cardiovascular disease CQMs.

Design

Longitudinal cohort study among 211 primary care practices in Colorado and New Mexico. Quarterly CQM reports were obtained from 178 (84.4%) practices. There was 100% response rate for baseline practice characteristics and implementation tracking surveys. Follow-up implementation tracking surveys were completed for 80.6% of practices.

Participants

Adult patients, staff, and clinicians in family medicine, general internal medicine, and mixed-specialty practices.

Intervention

Practices received 9 months of practice facilitation and health information technology support, plus biannual collaborative learning sessions.

Main Measures

This study identified practice characteristics associated with overall highest performance using area under the curve (AUC) analysis on aspirin therapy, blood pressure management, and smoking cessation CQMs.

Results

Among 178 practices, 39 were exemplars. Exemplars were more likely to be a Federally Qualified Health Center (69.2% vs 35.3%, p = 0.0006), have an underserved designation (69.2% vs 45.3%, p = 0.0083), and have higher percentage of patients with Medicaid (p < 0.0001). Exemplars reported greater use of cardiovascular disease registries (61.5% vs 29.5%,), standing orders (38.5 vs 22.3%) or electronic health record prompts (84.6% vs 49.6%) (all p < 0.05), were more likely to have medical home recognition (74.4% vs 43.2%, p = 0.0006), and reported greater implementation of building blocks of high-performing primary care: regular quality improvement team meetings (3.0 vs 2.2), patient experience survey (3.1 vs 2.2), and resources for patients to manage their health (3.0 vs 2.3). High improvers (n = 45) showed greater improvement implementing team-based care (32.8 vs 11.7, p = 0.0004) and population management (37.4 vs 20.5, p = 0.0057).

Conclusions

Multiple strategies—registries, prompts and protocols, patient self-management support, and patient-team partnership activities—were associated with delivering high-quality cardiovascular care over time, measured by CQMs.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT02515578

KEY WORDS: primary healthcare, quality indicators, practice facilitation, quality improvement, cardiovascular disease

INTRODUCTION

Clinical quality measures (CQMs) are now commonplace in healthcare as one source of measurement of the quality of care provided to patients. CQMs are required for prominent healthcare quality initiatives, including the Quality Payment Program from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid,1 the National Committee for Quality Assurance Patient Centered Medical Home recognition program,2 the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Uniform Data System program,3 and numerous national and regional programs.4 Ambulatory care practices use CQMs to measure quality improvement and to demonstrate value as part of alternative, value-based payment models.5 However, CQMs by themselves do not illustrate which types of practices do well on specific quality metrics or what practices do to achieve higher performance as measured by CQMs.6

In 2015, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) funded seven regional cooperatives to help primary care practices implement evidence to improve healthcare, build practice capacity to receive and incorporate new evidence, learn how external quality improvement support helps primary care practices, and improve the way practices work to improve the health of their patients.7 AHRQ was particularly interested in assessing and improving the delivery of cardiovascular care on four well-established guidelines: appropriate aspirin therapy, blood pressure control, cholesterol management, and smoking cessation. These four guideline have strong evidence for reducing patient risks of stroke or heart attack, or reducing the risk of developing heart disease.8–11

One of the funded cooperatives was EvidenceNOW Southwest, which aimed to improve the delivery of evidence-based guidelines in clinical practice in Colorado and New Mexico, using four cardiovascular care CQMs as one set of measures for evaluating outcomes.12, 13 Others have evaluated exemplary practices based on CQMs or colon cancer screening data using a single point in time.6, 14 The success of such pragmatic practice-based trials is often defined as the magnitude of improvement from baseline. In contrast, we sought to assess practice characteristics associated with CQM performance over time by including practices that both improved substantially or maintained high performance on CQMs. Practices began this initiative with varied levels of experience with quality improvement processes.15, 16 Some practices were novices in improving cardiovascular disease care; others had previously completed quality improvement initiatives, entering this study having already achieved high performance on one or more measures. Because practices began at different levels of CQMs, change over time on CQMs was not a good indicator of success that could be applied to all practices. Furthermore, practices value overall performance on quality measures and often seek guidance from other practices that maintain high performance or show great improvement in their measures.17, 18 Studying practices that include high improvers and high-achieving maintainers across multiple CQMs may point to important, changeable, and transferable tools and techniques for primary care practices.

This subanalysis of the EvidenceNOW Southwest project specifically aimed to identify practice characteristics associated with overall highest performance and highest improvement on aspirin therapy, blood pressure management, and smoking cessation CQMs.

METHODS

EvidenceNOW Southwest was a pragmatic trial conducted in primary care practices with 15 or fewer clinicians, located in Colorado and New Mexico. Practices received 9 months of practice facilitation support from trained Practice Facilitators and Clinical Health IT advisors, plus biannual collaborative learning sessions.12, 15 The practice support included guidance and resources for foundational practice improvement tools and techniques as well as help to extract and meaningfully use CQMs.19 EvidenceNOW Southwest enrolled 211 family medicine, general internal medicine, and mixed-primary practices that participated in the study between January 2015 and June 2018. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and the University of New Mexico Human Research Protections Office. Primary outcomes are reported elsewhere.20

Data Sources

Clinical Quality Measures

The funding agency specified the four targeted CQMs for all practices participating in the national EvidenceNOW initiative.16 The CQMs for aspirin use, blood pressure control, cholesterol management, and smoking cessation aligned with the National Quality Forum and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (Table 1).13 Specifications included a 12-month measurement period for each report. Enrolled practices reported at least one of the four CQMs each quarter (baseline through 6 months post-intervention). Practices could report CQMs to the study team by manually entering numerators and denominators in an online portal or by securely transferring patient-level information to the DARTNet Institute21 through structured flat files or direct EHR data extraction. The DARTNet Institute normalized the clinical data, calculated the CQMs, and reported results on the practice’s behalf.

Table 1.

EvidenceNOW Cardiovascular Disease Clinical Quality Measure (CQM) Definitions and Reference Numbers

|

Aspirin use* CMS Measure ID: CMS164v6; Version 6 NQF Number: 0068 |

Percentage of patients 18 years of age and older who were diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) or percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in the 12 months prior to the measurement period, or who had an active diagnosis of ischemic vascular disease (IVD) during the measurement period, and who had documentation of use of aspirin or another antiplatelet during the measurement period. |

|

Blood pressure control† CMS Measure ID: CMS165v7; Version7 NQF Number: 0018 |

Percentage of patients 18–85 years of age who had a diagnosis of hypertension and whose blood pressure was adequately controlled (< 140/90 mmHg) during the measurement period. |

|

Cholesterol management‡ CMS Measure ID: CMS347v3; Version 3 NQF: not applicable |

Percentage of high-risk adult patients aged = 21 years who were previously diagnosed with or currently have an active diagnosis of clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; or adult patients aged = 21 years with a fasting or direct low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level = 190 mg/dL; or patients aged 40 to 75 years with a diagnosis of diabetes with a fasting or direct low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of 70 to 189 mg/dL; who were prescribed or are already on statin medication therapy during the measurement year. |

|

Smoking cessation§ CMS Measure ID: CMS138v6; Version 6 NQF Number: 0028 |

Percentage of patients aged 18 years and older who were screened for tobacco use one or more times within 24 months and who received tobacco cessation intervention if identified as a tobacco user. |

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, NQF National Quality Forum

*Source: eCQI Resource Center. Ischemic vascular disease (IVD): use of aspirin or another antiplatelet. https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqm/ep/2018/cms164v6. Accessed October 18, 2019

†Source: eCQI Resource Center. Controlling high blood pressure. https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqm/measures/cms165v6. Accessed October 18, 2019

‡Source: eCQI Resource Center. Statin therapy for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqm/ep/2020/cms347v3. Accessed October 18, 2019

§Source: eCQI Resource Center. Preventive care and screening: tobacco use: screening and cessation intervention. https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqm/measures/cms138v6. Accessed October 18, 2019

We used all available data reported by practices by June 1, 2018, the end of the final quarter for required CQMs for the analysis reported here. Not all practices were able to report CQMs by this date. These data did not comprise the final CQM dataset used in later project analyses, which included chart audit data for practices unable to report CQMs. The cholesterol management CQM was not included in this analysis due to insufficient data.

Practice Surveys

Baseline practice surveys and practice member surveys were completed during study enrollment. The surveys were designed in collaboration with the national EvidenceNOW evaluation team.15, 16 One 48-item practice survey per practice was completed by a lead administrator and lead clinician to gather descriptive information at the practice and organizational level. The practice survey included the Change Process Capability Questionnaire, an assessment of quality improvement strategies.22 All practice clinicians and staff members were asked to complete the Practice Member Survey, a 39-item survey designed to gather information about member characteristics and their perceptions of practice function. A minimum response rate of 70% of practice members was targeted from each practice.

Implementation Tracker

The conceptual and operational framework for the practice facilitation intervention was based on six foundational Building Blocks for High-Performing Primary Care: engaged leadership, data-driven improvement, empanelment, team-based care, patient-team partnership, and population management.23 To assist practice facilitators in rating practices’ progress on the six building blocks, the study team developed the 24-item Implementation Tracker to document quarterly progress (at baseline, 3, 6, and 9 months) on each building block as: “not started or no activity”; “in progress, working toward”; or “completed or is now regular, ongoing.”

CQM Analysis

Area under the curve (AUC) analysis assessed overall performance to identify practices that showed greater improvement or greater sustained high performance on CQMs.24 To operationalize a measure representing performance in practices with varying trajectories, we calculated total area under the curve over the reporting periods for each CQM for practices that had reported at least three quarters of data (standardized to 12 months) and averaged across the three CQMs, thus capturing patients’ overall exposure to high-quality care across the reporting periods. We used random coefficient models (general linear mixed models) to generate individual baseline and slope estimates, which were used in standard mathematical formulas to compute AUCs. Other clinical studies have used AUC to combine multiple measures over time to reflect total quantity of a variable for a specified time span and then used the combined measure as an outcome or predictor.25–27 In this context, where some practices have already met high benchmarks for quality measures and are focused on sustaining their quality improvement achievements, an easily calculated measure of cumulative performance to identify “exemplar” practices has distinct advantages over traditional approaches that often base success only on improvement (i.e., slopes). For this analysis, “exemplar” practices were defined as the top quartile based on the combined AUC across all three CQMs; non-exemplar practices were below the top quartile.

A second analysis identified practices that demonstrated overall greater improvement on their CQMs using random coefficient models (general linear mixed models), which can generate individual slope estimates for each practice. Practices that had an average improvement across the three CQMs of 5% or more per year were selected as “high improvers.” The high improver group included five exemplar practices identified in the AUC analysis. Practices that were previously identified as “exemplars” were excluded from the comparison group for high improvers.

Survey Analysis

To compare characteristics of exemplar and non-exemplar practices or high improver and non-high improver practices, we used baseline practice survey responses. We calculated summary statistics (frequencies and means) for all participating practices by exemplar or improver status. Practice survey items described ownership, practice size (number of clinicians), payer mix, medically underserved area designation, use of patient registries for chronic disease prevention and management, adoption of clinical guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention and management (agreed upon, posted, standing orders, or EHR prompts), accountable care organization membership, patient-centered medical home designation, use of an empanelment and panel management system, participation in stage one of meaningful use, and past experience with a practice support organization. The practice survey also included items reporting practice activity related to the building blocks of high-performing primary care. We categorized practices’ geographic area as rural or non-rural using the US Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes associated with practice ZIP code.28 We examined the differences between exemplar and non-exemplar practices on multiple practice-level variables of interest using chi-square tests and t tests. All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical software (Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

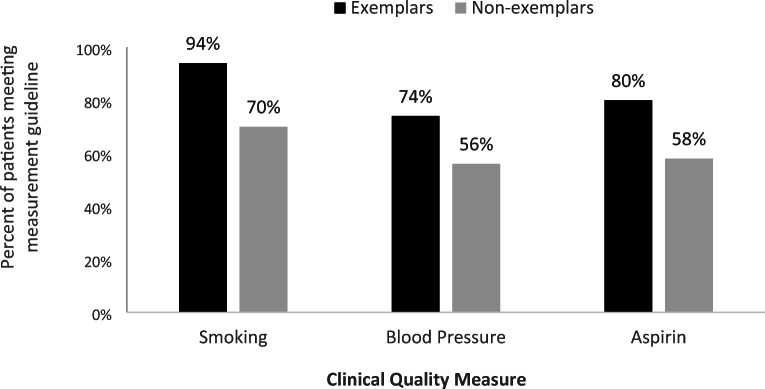

Of the 211 enrolled EvidenceNOW Southwest practices, 211 (100%) completed baseline surveys and 178 (84.4%) submitted sufficient data for inclusion in the AUC analysis. Based on the AUC analysis, 39 practices were identified as exemplars; that is, practices that showed greatest improvement or greatest sustained high performance. The mean AUC for each of the three measures differed between the two groups, with exemplars exhibiting notably higher percentages of patients meeting or exceeding the measurement guideline (Fig. 1). Although the maximum AUC for some non-exemplars were similar to exemplars on individual measures, they did not appear in the exemplar group because they did not have a high enough combined AUC from all three measures in our analysis. The AUC represents cumulative performance over time, standardized to a 12-month period (per year) for interpretability.

Figure 1.

Average (mean) clinical quality measure cumulative performance over time (measured by the area under the curve) by exemplar (n = 39) and non-exemplar practices (n = 139). Bars represent the percentage of patients meeting or exceeding the measurement guideline for the smoking cessation, blood pressure control, and aspirin therapy clinical quality measures.

Characteristics of Exemplar Versus Non-exemplar Practices

Exemplars and non-exemplars did not differ in practice size, rurality, empanelment, previous “meaningful use” participation, previous work with a practice facilitation support organization, or membership in an accountable care organization (Table 2). Exemplars were more likely to be a Federally Qualified Health Center and have a higher percentage of patients covered by Medicaid, commercial payers, or no insurance (all p < 0.05). Among characteristics that might be changeable through practice improvement efforts, exemplar practices were more likely to have implemented cardiovascular disease-related registries, implemented cardiovascular disease guideline prompts and standing orders, held regular quality improvement team meetings, used regular patient experience surveys to guide care improvements, and provided patients with resources for self-management between office visits (all p < 0.05). Exemplar practices were also more likely to report higher scores on change management processes. Practice facilitators rated implementation of the patient-team partnership and population management building blocks higher among exemplar practices at baseline.

Table 2.

Baseline Practice Characteristics, Overall and by Exemplar and Non-exemplar Practices

| All practices N = 211 |

Non-exemplar N = 139 |

Exemplar N = 39 |

p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % or mean (SD) | % or mean (SD) | % or mean (SD) | ||

| Practice size (number of clinicians) | 3.5 (2.6) | 3.41 (2.97) | 3.79 (3.01) | 0.4004 |

| Geographic area | ||||

| Rural | 28.9% | 31.7% | 23.1% | 0.301 |

| Urban/suburban | 71.1% | 68.4% | 76.9% | |

| System for empanelment | 78.2% | 78.4% | 82.1% | 0.621 |

| “Meaningful use” stage 1 participation (yes) | 67.8% | 66.2% | 66.7% | 0.955 |

| Previous work with support organization (yes) | 65.4% | 61.9% | 74.4% | 0.15 |

| Accountable care organization member (yes) | 47.4% | 41.0% | 56.4% | 0.087 |

| Practice ownership | ||||

| Clinician | 47.9% | 52.2% | 28.2% | < 0.001 |

| Hospital/academic center | 15.6% | 12.2% | 2.6% | |

| Federally Qualified Health Center or similar | 36.5% | 35.3% | 69.2% | |

| Payers (% of patients covered) | ||||

| Commercial | 37.55 (25.23) | 38.05 (24.74) | 24.29 (3.88) | 0.005 |

| No insurance | 11.21 (13.89) | 11.28 (14.37) | 17.04 (14.31) | 0.035 |

| Medicaid | 27.43 (22.08) | 25.58 (18.73) | 41.48 (25.54) | < 0.001 |

| Medicare | 18.74 (13.99) | 19.74 (17.18) | 15.91 (20.30) | 0.164 |

| Underserved designation | 45.0% | 45.3% | 69.2% | 0.008 |

| Registries | ||||

| Risk | 35.1% | 33.8% | 53.9% | 0.023 |

| Diabetes | 64.0% | 60.4% | 76.9% | 0.058 |

| Cholesterol | 44.6% | 46.0% | 66.7% | 0.023 |

| Hypertension | 54.0% | 55.4% | 71.8% | 0.066 |

| Ischemic vascular disease | 37.9% | 29.5% | 61.5% | < 0.001 |

| Prevention | 53.6% | 48.9% | 66.7% | 0.05 |

| Number of registries | 2.89 (2.38) | 2.74 (2.42) | 3.97 (2.47) | 0.006 |

| Adoption of CVD clinical guidelines for prevention | ||||

| Posted | 26.4% | 22.3% | 41.0% | 0.019 |

| Agreed upon | 54.5% | 54.0% | 56.4% | 0.786 |

| EHR prompt | 59.6% | 51.1% | 89.7% | < 0.001 |

| Standing orders | 30.3% | 25.2% | 48.7% | 0.005 |

| Adoption of CVD clinical guidelines for management | ||||

| Posted | 32.7% | 24.5% | 41.0% | 0.042 |

| Agreed upon | 55.5% | 48.9% | 59.0% | 0.267 |

| EHR prompt | 56.4% | 49.6% | 84.6% | < 0.001 |

| Standing orders | 29.9% | 22.3% | 38.5% | 0.042 |

| Sum of above | 1.74 (1.37) | 1.45 (1.22) | 2.23 (1.35) | < 0.001 |

| PCMH recognized | 44.6% | 43.2% | 74.4% | < 0.001 |

| Practice survey “building blocks” | ||||

| Quality improvement team meets regularly | 2.41 (1.46) | 2.19 (1.46) | 3.00 (1.06) | 0.002 |

| System for empanelment | 2.07 (1.43) | 1.97 (1.41) | 2.64 (1.38) | 0.012 |

| Patient experience survey to monitor performance | 2.43 (1.60) | 2.24 (1.97) | 3.13 (1.36) | 0.002 |

| Patients provided with resources to manage health | 2.47 (1.11) | 2.32 (2.13) | 2.97 (0.85) | 0.001 |

| Strategies to improve CVD care (from the Change Process Capability Questionnaire) | ||||

| Total score | 7.12 (12.58) | 4.97 (12.79) | 13.36 (8.80) | < 0.001 |

| Information and skills training | 3.85 (0.97) | 3.68 (1.00) | 4.24 (0.68) | 0.002 |

| Opinion leaders, role modeling to encourage support for changes | 3.39 (1.18) | 3.27 (1.20) | 3.42 (1.18) | 0.524 |

| Systems to provide high-quality care | 3.94 (1.07) | 3.83 (1.08) | 4.33 (0.87) | 0.008 |

| Remove/reduce barriers | 3.82 (1.05) | 3.72 (1.11) | 4.03 (0.75) | 0.113 |

| Teams for change process | 3.72 (1.21) | 3.57 (1.22) | 4.11 (0.97) | 0.014 |

| Delegating to non-clinicians | 3.30 (1.34) | 3.18 (0.12) | 3.61 (1.38) | 0.089 |

| Power to authorize and make change | 3.58 (1.08) | 3.54 (1.10) | 3.50 (0.91) | 0.854 |

| Periodic measurement | 3.63 (1.20) | 3.44 (1.24) | 4.27 (0.69) | < 0.001 |

| Reporting practice performance | 3.50 (1.43) | 3.24 (1.43) | 4.47 (0.92) | < 0.001 |

| Goals and benchmarking | 3.46 (1.48) | 3.23 (1.47) | 4.42 (1.06) | < 0.001 |

| Customize implementation of CVD prevention care changes to practice | 3.22 (1.36) | 3.04 (2.81) | 3.84 (3.45) | 0.001 |

| Rapid-cycling, piloting, pre-testing | 2.89 (1.26) | 2.72 (1.23) | 3.47 (1.02) | 0.001 |

| Design improvements for less clinician work | 2.21 (1.23) | 3.07 (1.21) | 3.69 (1.09) | 0.006 |

| Designing improvements more beneficial to patients | 3.56 (1.20) | 3.39 (1.20) | 3.89 (1.05) | 0.022 |

| Implementation tracking note “building blocks” (rated by practice facilitator) | ||||

| Engaged leadership | 45.08 (23.84) | 44.30 (25.03) | 47.95 (18.94) | 0.398 |

| Data-driven improvement | 37.73 (27.57) | 39.23 (26.98) | 32.31 (29.33) | 0.167 |

| Empanelment | 66.30 (40.44) | 63.73 (41.39) | 75.64 (36.04) | 0.104 |

| Team-based care | 48.69 (32.15) | 47.62 (31.30) | 52.56 (35.26) | 0.397 |

| Patient-team partnership | 32.04 (22.31) | 27.93 (19.50) | 47.01 (25.54) | < 0.001 |

| Population management | 36.19 (32.05) | 32.04 (29.91) | 51.28 (35.33) | < 0.001 |

CVD cardiovascular disease, EHR electronic health record, PCMH patient-centered medical home

*Italic text indicates significance with p value of less than 0.05 at 95% confidence interval

Characteristics of High Improver Versus Non-high Improver Practices

The second analysis specifically sought to identify and characterize practices that improved by more than 5% per year, on average, by examining average slopes of the CQMs over time. These 45 EvidenceNOW Southwest practices were designated as high improvers (Table 3). Five of the 45 practices that were identified as high improvers in the slopes analysis had also been identified as exemplars in the AUC analysis. To better understand important practice characteristics, we compared high improvers (which included 40 non-exemplars and 5 exemplars for a total of 45) to the remaining practices after excluding exemplars that were not designated as high improvers (n = 99).

Table 3.

Building Block Implementation Mean Scores for Exemplar, Non-exemplar, High Improvers, and Non-high Improvers at Baseline and from Baseline to 9 Months

| Implementation tracking note building blocks | Exemplars vs. non-exemplars based on AUC analysis* |

High improvers vs. non-high improvers based on average slopes* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exemplar N = 39 | Non-exemplar N = 137† | p value‡ | High improver N = 45 |

Non-high improver N = 99 |

p value | |

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | |||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Leadership | 47.95 | 45.04 | 0.502 | 45.11 | 45.15 | 0.992 |

| Data-driven improvement | 32.31 | 39.42 | 0.16 | 34.44 | 40.93 | 0.187 |

| Team-based care | 52.56 | 48.36 | 0.474 | 35.83 | 53.87 | 0.001 |

| Patient-team partnership | 47.01 | 28.22 | < 0.001 | 22.41 | 30.84 | 0.016 |

| Population management | 51.28 | 32.48 | 0.001 | 24.07 | 36.60 | 0.02 |

|

Mean change N = 39 |

Mean change N = 131 |

p value |

Mean change N = 45 |

Mean change N = 91 |

p value | |

| Baseline to 9 months | ||||||

| Leadership | 37.69 | 30.99 | 0.222 | 32.44 | 31.32 | 0.846 |

| Data-driven improvement | 54.87 | 36.72 | 0.007 | 44.67 | 34.62 | 0.117 |

| Team-based care | 22.44 | 17.94 | 0.431 | 32.78 | 11.68 | < 0.001 |

| Patient-team partnership | 14.74 | 16.48 | 0.516 | 19.26 | 15.29 | 0.167 |

| Population management | 29.06 | 25.19 | 0.515 | 37.41 | 20.51 | 0.006 |

*AUC, area under the curve; less than 5% missing data on any given variable. Ns represent the number of practices with available survey data, which may be slightly lower than the total number of practices in other analyses

†Five exemplar practices were also high improvers (there were no practices in this group designated exemplar)

‡Italic text indicates significance with p value of less than 0.05

High improvers had almost no significant differences from non-high improvers on baseline characteristics (same list as in Table 2). High improvers had lower baseline percentages (p < 0.01) of implementing standing orders for “cardiovascular disease clinical guidelines for management” and “cardiovascular disease clinical guidelines for prevention.” High improvers were also significantly lower on their baseline implementation of three of five building blocks (Table 3) than non-high improvers (excluding exemplars). In contrast, exemplar practices were, at baseline, significantly higher than non-exemplars on their implementation of two of the five building blocks, patient-team partnership and population management.

Change over Time on Building Blocks of High-Performing Primary Care

At 9 months from baseline, all four (non-mutually exclusive) groups—exemplars, non-exemplars, high improvers, and non-high improvers—reported improvements in their combined mean building block scores (all p < 0.01). Compared to non-exemplars, exemplars showed greater improvement on data-driven improvement (p = 0.0066). Compared to non-high improvers, high improvers showed greater improvement on team-based care (p = 0.0004) and population management (p = 0.0057).

DISCUSSION

Based on AUC analysis of cardiovascular disease-related CQM performance, exemplar practices in EvidenceNOW Southwest were more likely to use patient registries, formally adopt and implement specific actions around cardiovascular disease guidelines, have patient-centered medical home recognition, implement foundational building blocks of high-performing primary care, and exhibit more advanced patient-team partnerships and population management activities (Table 4). Exemplar practices also improved more on the data-driven quality improvement building block of high-performing primary care. These results demonstrate that practices with higher cumulative performance on CQMs through the EvidenceNOW Southwest initiative started with relative advantages (i.e., having multiple processes, policies, tools, and support systems already in place) and may have devoted extra attention to data-driven quality improvement.

Table 4.

Summary of Characteristics and Improvement Strategies of High-Performing Practices

|

Characteristics • Federally Qualified Health Center • Higher proportion of Medicaid or no insurance | |

|

Improvement tools and strategies • EHR prompts • Standing orders • Registries • Teams for change process • Quality improvement team meets regularly • System for empanelment • Patient experience survey to monitor performance • Patients provided with resources to manage health • Periodic measurement • Reporting practice performance • Goals and benchmarking • Customize implementation of cardiovascular disease prevention care changes to practice • Rapid-cycling, piloting, pre-testing • Design improvements for less clinician work • Designing improvements more beneficial to patients | |

|

Building blocks of high-performing primary care • Team-based care • Data-driven improvement • Patient-team partnership • Population management |

Meanwhile, practices that improved more on CQMs through EvidenceNOW Southwest started with no relative advantages but were able to improve their CQMs while showing greater implementation of two of five building blocks of high-performing primary care. The high improvers built practice team-based care systems and established population management systems, which might have accounted for their greater improvement.

The presence of multiple components and capabilities upon entry into an intervention may be particularly important when assessing the care that patients receive. Federally Qualified Health Centers comprised the largest proportion of exemplar practices in our sample (69%), which may reflect well-established quality improvement efforts and sustained quality measure reporting under the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Uniform Data System for grantee health centers.3 While Federally Qualified Health Centers and system practices were the majority of exemplars, smaller, independent practices comprised more than one quarter of the 39 exemplars.

Though our analyses examined overall performance and change in quality measures, the results are consistent with other reports on attributes of high-performing primary care practices. A study of primary care archetypes and characteristics of high-performers on clinical guidelines noted important commonalities: use of multiple strategies, a leader who prioritized performance, and use of care plans and patient education to ensure patient role in guideline adherence.29 Another study of exemplars (defined there as top tertile in guideline care at a single point in time) found that reported use of EHR reminders, standing orders, staff education, and patient education were positively correlated with quality measure performance for some measures, including cardiovascular disease measures.6 Similarly, our data demonstrated that multiple strategies were implemented among high-performing practices (e.g., registries, prompts and protocols, patient self-management support resources, and patient-team partnership activities). A European study among general practitioners found higher implementation of five practice-level prevention service activities were associated with higher cardiovascular disease performance scores both independently and as a combined score.30 Our results further align with a qualitative study of a family medicine medical group, which found exemplars had, among their attributes, a strong team orientation, strong change and improvement orientation, support for physician-patient relationship, and emphasis on patient-centeredness.31 Lastly, our study provides empirical support that implementing the 10 building blocks of high-performing care23 (including data-driven improvement, team-based care, patient-team partnership, and population management) improves performance on cardiovascular CQMs. For patients with cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular disease risks, the results suggest that implementing principles of the patient-centered medical home2 may improve important care processes for reducing their risk of stroke and heart attack, as well as improving CQMs increasingly being used as indications of value in alternative payment models.

Limitations

Reporting CQMs is difficult.13 Practices not reporting CQMs over time were excluded because AUC requires multiple data points per practice; however, excluded practices may have been providing high-quality care to their patients. If further statistical analyses are required after practices are identified as exemplars, a sufficient number of practices will be needed in the exemplar group to conduct these analyses. Setting a benchmark too high may identify too few exemplar practices for analysis; adjusting the benchmark criteria lower may be needed. This analysis did not establish which combinations of characteristics are essential for exemplary performance, though the analysis suggests that implementing more than one CVD-related registry and implementing guidelines in multiple ways were important distinguishing features of exemplary practices. The cost of implementing PCMH or quality improvement activities may be a barrier for primary care practices.32, 33 Finally, CQMs are not the only important or relevant measures of high-quality primary care. There may be other more relevant, patient-valued methods to assess quality in complex adaptive systems such as primary care.34

Conclusions

AHRQ’s EvidenceNOW initiative aimed to “build practice capacity to receive and incorporate evidence in the future” and “improve the way they work and improve the health of their patients.” Our analysis suggests that primary practices with well-established capacity or that build capacity in multiple improvement strategies are more likely to demonstrate higher performance on clinical quality measures of cardiovascular care. These strategies include building blocks of high-performing care, such as registries, prompts and protocols, patient self-management support, and patient-team partnership activities. While further research may identify the specific combinations of characteristics and associated mechanisms leading to sustained improvements, primary care practices and their patients may well benefit from continued support to establish and maintain multiple improvement processes, policies, tools, and support systems.

Funding Information

This research was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (Grant No. R18HS023904).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program. https://qpp.cms.gov. Published 2019. Accessed 08/28/2019.

- 2.National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). NCQA Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) Standards and Guidelines. 2017 Edition, Version 2 (Effective September 30, 2017) ed. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA); 2017.

- 3.Health Resources and Services Administration. Uniform Data System: Reporting Tables for the 2019 Health Center Data. In: Bureau of Primary Health Care, ed: Health Resources and Services Administration; 2019.

- 4.Panzer RJ, Gitomer RS, Greene WH, Webster PR, Landry KR, Riccobono CA. Increasing demands for quality measurement increasing demands for quality measurement. JAMA. 2013;310(18):1971–1980. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litvin CB, Ornstein SM, Wessell AM, Nemeth LS. “Meaningful” clinical quality measures for primary care physicians. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(10):e583–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ornstein SM, Nemeth LS, Nietert PJ, Jenkins RG, Wessell AM, Litvin CB. Learning from primary care meaningful use exemplars. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(3):360–370. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.03.140219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen DJ, Balasubramanian BA, Gordon L, et al. A national evaluation of a dissemination and implementation initiative to enhance primary care practice capacity and improve cardiovascular disease care: the ESCALATES study protocol. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0449-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):435–443. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siu AL. for the USPSTF. Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):622–634. doi: 10.7326/M15-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith Sidney C, Benjamin Emelia J, Bonow Robert O, et al. AHA/ACCF Secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update. Circulation. 2011;124(22):2458–2473. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318235eb4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ C. Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.English AF, Dickinson LM, Zittleman L, et al. A community engagement method to design patient engagement materials for cardiovascular health. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(Suppl 1):S58–S64. doi: 10.1370/afm.2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knierim KE, Hall TL, Dickinson LM, et al. Primary care practices’ ability to report electronic clinical quality measures in the EvidenceNOW Southwest initiative to improve heart health primary care practice reporting of electronic clinical quality measures. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198569–e198569. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemeth LS, Nietert PJ, Ornstein SM. High performance in screening for colorectal cancer: a Practice Partner Research Network (PPRNet) case study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(2):141–146. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.02.080108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall TL, Knierim KE, Nease DE, Jr, et al. Primary care practices’ implementation of patient-team partnership: findings from EvidenceNOW Southwest. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(4):490–504. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindner S, Solberg LI, Miller WL, et al. Does ownership make a difference in primary care practice? J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(3):398–407. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.03.180271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKee MD, Alderman E, York DV, et al. A learning collaborative approach to improve primary care STI screening. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2018;57(8):895–903. doi: 10.1177/0009922817733702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubenstein LV, Stockdale SE, Sapir N, et al. A patient-centered primary care practice approach using evidence-based quality improvement: rationale, methods, and early assessment of implementation. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(Suppl 2):S589–597. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2703-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernald D, Wearner R, Dickinson WP. Supporting primary care practices in building capacity to use health information data. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2014;2(3):1094. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickinson WP, Nease DE Jr, Rhyne RL, et al. Practice Transformation support and patient engagement to improve cardiovascular care: a report from EvidenceNOW Southwest. J Am Board Fam Med. In Press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.DARTNet Institute. DARTNet website. http://www.dartnet.info/. Accessed August 16, 2018

- 22.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Margolis KL, Whitebird RR. Measuring an organization’s ability to manage change: the change process capability questionnaire and its use for improving depression care. Am J Med Qual. 2008;23(3):193–200. doi: 10.1177/1062860608314942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):166–171. doi: 10.1370/afm.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Britton J, Tattersfield A. Comparison of cumulative and non-cumulative techniques to measure dose-response curves for beta agonists in patients with asthma. Thorax. 1984;39(8):597–599. doi: 10.1136/thx.39.8.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joerger M, Huitema AD, Krahenbuhl S, et al. Methotrexate area under the curve is an important outcome predictor in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: a pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis from the IELSG no. 20 trial. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(4):673–677. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeh S. Using trapezoidal rule for the area under a curve calculation. In: Proceedings of the 27th Annual SAS Users Group International Conference.2002

- 27.Whitelaw DC, Clark PM, Smith JM, Nattrass M. Effects of the new oral hypoglycaemic agent nateglinide on insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2000;17(3):225–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comartie J. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/ Published 2016. Accessed

- 29.Feifer C, Nemeth L, Nietert PJ, et al. Different paths to high-quality care: three archetypes of top-performing practice sites. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(3):233–241. doi: 10.1370/afm.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ludt S, Campbell SM, Petek D, et al. Which practice characteristics are associated with the quality of cardiovascular disease prevention in European primary care? Implement Sci. 2013;8:27. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solberg LI, Hroscikoski MC, Sperl-Hillen JM, Harper PG, Crabtree BF. Transforming medical care: case study of an exemplary, small medical group. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(2):109–116. doi: 10.1370/afm.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel MS, Arron MJ, Sinsky TA, et al. Estimating the staffing infrastructure for a patient-centered medical home. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):509–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magill MK, Ehrenberger D, Scammon DL, et al. The cost of sustaining a patient-centered medical home: experience from 2 states. Ann Family Med. 2015;13(5):429–435. doi: 10.1370/afm.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young RA, Roberts RG, Holden RJ. The challenges of measuring, improving, and reporting quality in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):175–182. doi: 10.1370/afm.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]