Abstract

This paper summarizes the impact of COVID-19 (through mid-September 2020) on the U.S. labor market through the lens of measures found in monthly Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Situation releases. It describes the pandemic’s impact thus far by looking at payroll jobs, the unemployment rate, a broader measure of job disruptions, and disparities by race and sex. The conclusion discusses forces that will drive outcomes in the coming months. The findings are as follows: (1) The COVID-19 shock was very abrupt and deep by historical standards, and headline numbers understate the magnitude of job disruptions. (2) The pace of the jobs recovery has slowed markedly since June. (3) The share of disrupted workers with ties to employers, which began very high, is falling rapidly, dimming prospects for further rapid recovery. (4) Hispanic, African American and women workers’ jobs were more disrupted than others’. (5) Prospects for a speedy jobs recovery depend strongly on the path of the pandemic and degree of fiscal stimulus, both aided by official statistics to guide decisions at all levels during this critical time.

Keywords: COVID-19, Recession, Labor market, Unemployment, Jobs, Layoffs

Introduction

Perhaps only students of pandemics were not surprised by the rapid and massive impact of COVID-19 on the national and global economy. Certainly, few economists have analyzed policy and behavioral shocks of the breadth and depth that the U.S. has sustained since February 2020. The goal of this paper is to summarize, as of mid-September 2020, the impact of COVID-19 on a significant part of the U.S. economy, its labor market.

The labor market is the largest and most complex market in the country. Furthermore, its outcomes affect the living standards of virtually all Americans. Thus, by examining the labor market, we can begin to assess the impact of the pandemic beyond the direct suffering it has caused through illness, deaths, disability and more.

This article proceeds as follows. Section 2 lays the groundwork by reviewing the measurement of labor market conditions, primarily from the monthly Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Situation releases.

The main body addresses three big questions that help frame the discussion. The first question is what has happened so far to overall labor market conditions? To answer this, I look at measures of depth and abruptness, as well as the dimensions of the recovery since April, by looking at payroll jobs (Sect. 3) and the unemployment rate along with a broader measure of job disruptions (Sect. 4).

The second question is who has been affected most, by race and sex (Sect. 5).

Third, how does the information help inform expectations going forward? The conclusion (Sect. 6) summarizes the previous sections and then discusses the forces that will drive labor market outcomes in the coming months and some implications for official labor market statistics.

Measurement of labor market conditions

This paper relies largely on statistics contained in the monthly Employment Situation “jobs report,” issued by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). As the most timely, comprehensive, historically comparable and authoritative gauge of the state of the U.S. economy, this release always moves financial markets. Even in less turbulent times, no other statistical release gets anything close to the attention received by the Employment Situation.

The release includes two distinct “headline” indicators: (1) the national unemployment rate and (2) the change in payroll jobs. Drawn from separate surveys (of households and employers), both measure conditions at the middle of the month, but do it differently. Of course, in addition to the headline numbers, the Employment Situation reports thousands of other statistics. This paper uses that information to assess what share of U.S. workers’ primary jobs have been disrupted, how much has been recovered already and whether the disruption may be temporary or permanent.

One could ask whether there are better sources of timely labor market data than the Employment Situation. In my view, other sources offer valuable corroboration, additional detail or interim measures, but they are no substitute for these official statistics. To be specific, initial or continuing claims for unemployment insurance (published by the Employment and Training Administration) are more timely and frequent, but not as comprehensive, and are affected by operational and policy quirks. Alternatively, the increasing number of novel private sector measures add helpful color and may be more timely, but are less comprehensive, have less transparent methodologies and short histories.

The three general reasons to question the quality of a statistic are data integrity, methodological flaws, and response rates. Fortunately, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as an independent, professional, national statistical agency, is well-positioned to deal with these issues.

Beginning with integrity, BLS is headed by Commissioner William Beach, a presidential appointee with a scientific background and a 4-year fixed term, which means he does not serve at the pleasure of the president. The commissioner is the only appointee in the bureau and sees statistical estimates only after the staff declares them final. The staff maintains data integrity by fostering an exceptional internal culture via agency directives, practices and training; following Office of Management and Budget statistical policy directives, conducting background checks; and being subject to many forms of scrutiny, including the Department of Labor’s Office of the Inspector General, the General Accountability Office, and Congressional committees, not to mention media and public attention.1 Further reassurance about statistics from the Employment Situation comes from having independent employer and household surveys, whose patterns are generally mutually reinforcing. Manipulating either without detection would be basically impossible, and so much more so to tamper with both.

In addition, BLS maintains its world-class reputation by being transparent about its methods, engaging with experts and modernizing over time. Check out the documentation in its Handbook of Methods (https://www.bls.gov/opub/hom/) and the wealth of technical notes attached to every release. Since all data have limitations, the agency’s strategy is to be fully transparent about the methods, virtues and limitations of all of its products. To help improve its data, it has a number of advisory committees to provide input from technical, academic, and user communities.2

Of course, the pandemic has interfered with data collection and raised questions beyond the ones normally included in the jobs report. Thus, every month since March, the bureau has published an accompanying statement about COVID-19-related methodological issues and how it managed them. The recent adjustments to methodology include movement largely to electronic data collection, conversion from multiplicative to additive seasonal adjustment factors, adoption of a more sensitive birth–death model for the payroll survey, and adding COVID-19-related questions to the household survey.

In 2008, during the throes of layoffs from the developing financial crisis, policymakers relied heavily on monthly payroll job estimates to assess the depth of the downturn. Later, through its annual rebenchmarking process, BLS determined that the real-time estimates strongly underestimated actual job losses.3 Based on subsequent research, starting this April, the bureau began applying a new method to incorporate the impact of establishment births and deaths on payroll jobs estimates in order to account for COVID-19-related impacts. This change addresses the tendency of the normal methods of estimating establishment formations and dissolutions to underestimate payroll job changes around economic turning points.4 The goal is to avoid large downward rebenchmarking revisions for 2020.

The main ongoing challenges concern response rates and misclassification errors. For a discussion of misclassification errors see Sect. 4. With respect to response rates, as with most bureau surveys, participation in the two Employment Situation programs is voluntary. In general, the bureau obtains far higher survey response rates than those achieved in private sector polls.5 This high participation reflects respondents’ willingness to provide an important public service, and bureau efforts to educate them and minimize burden and risk. Not surprisingly, pandemic-related disruptions to families, employers and survey field operations suppressed response rates to both Employment Situation surveys beginning in March.6 Fortunately, the response rates have been sufficient to meet the bureau’s quality standards. In addition, participation has improved since April, particularly for the payroll survey, which has returned close to normal levels.

Payroll jobs: how job losses compare to past recessions

The number of payroll jobs measures how many workers were on employer payrolls each month, based on a monthly survey of about 530,000 workplaces, produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Employment Statistics program.7 This measure has many important virtues.8 This simple concept hews close to most people’s concerns about recessions. BLS has measured it essentially the same way since the 1940s. Payroll jobs correlate well with other measures of the business cycle, such as gross domestic product. And, jobs can be measured well across all parts of the economy. Finally, research shows that it is a reliable indicator of trends and comparisons to the past—and becomes even more so after it is revised and rebenchmarked.

Jobs lost and regained

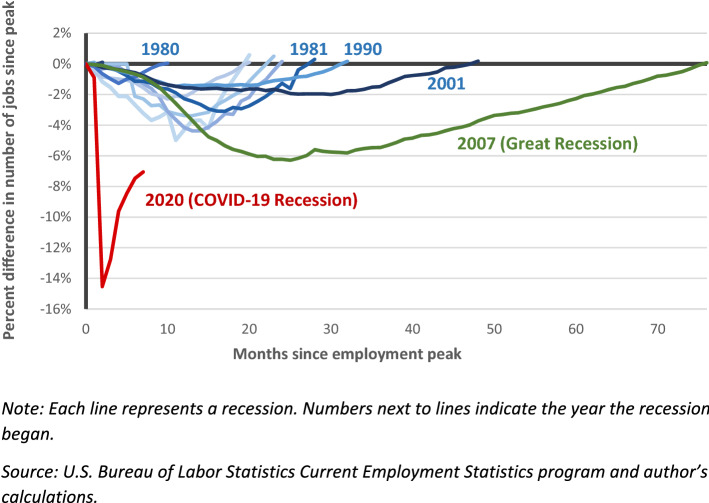

How does the jobs impact to date of the COVID-19 recession compare to previous downturns? Economists often track recessions by comparing their impact on key indicators to previous downturns’ patterns. Each recession has a different depth, speed of job loss and speed of job recovery. To see this, the Fig. 1 lines track all the post-war recessions. For each recession, we begin with the month before payroll job losses began; we call that the “peak month.” Then we can track the percentage of jobs lost during the downturn until the month that the number of jobs returns to its pre-recession peak.

Fig. 1.

Payroll job losses during COVID-19 recession compared to post-WWII recessions

Figure 1 labels the current recession and the previous three. First, we can focus on the declines in jobs after the peak. This identifies two features of the COVID-19 recession job losses:

Deepest ever: By April, about fifteen percent of peak jobs were gone, compared to the previous maximum of six percent during the Great Recession. That reflects the loss of 22 million jobs from February to April.

Most abrupt: Previous recessions built up over time. Job losses continued for at least five months for previous recessions, while (if we have no further large-scale shutdowns) this recession reached its deepest point after just two months of losses.

Turning to the recovery of jobs, note that after the jobs troughs, regaining jobs took far more time than losing them. Indeed, the most recent downturns (1990, 2001 and 2007) were termed “jobless recoveries,” because they had very slow job growth after the losses stopped. The April to September jobs recovery during the COVID recession has three key features:

Fastest job regaining pace ever: So far, we’ve added a higher percentage of jobs per month than in previous recessions. This is no doubt due to pervasive temporary layoffs and recalls stemming from virus-related shutdowns.

Hole is still deep: Although half (52 percent) of lost jobs are back, we are still down about seven percent from the peak. Although this means that almost half of the jobs lost have been recovered, we still have more losses than the six percent losses at the jobs low point of the Great Recession.

Pace now slowing noticeably: The strong early pace of COVID-19 jobs recovery weakened noticeably in July, August and September.

Industry impact

Not surprisingly, COVID-19’s impact varied strongly by industrial sector. The impact of the COVID-19 recession varies among industries for at least four reasons:

Restrictions, relaxations and cautious behavior affected industries differently;

Some industries always tend to be cyclical;

Industries that are currently growing tend to be more protected and recover quickly while those that are shrinking tend to be vulnerable and slow to recover; and

The pandemic altered needs and trade patterns for some products and services, perhaps permanently.

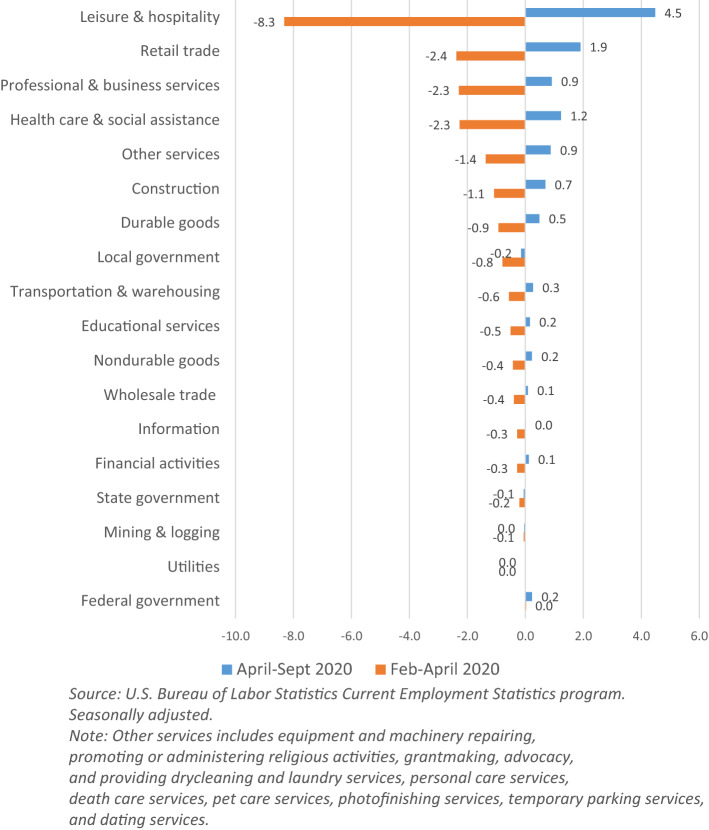

Looking by industry sector shows that most of the post-April job growth reversed pre-April losses, as the first reason suggests. Figure 2 shows net job changes by major industry sector for two periods, from February to April (the shutdown period) and from April to September (the rebound so far). Industries are sorted by job losses from February to April. The chart shows the strong symmetry between job losses during the shutdown and subsequent growth. As about half of the lost jobs returned, most sectors showed gains around half of their losses during the shutdown. The correlation coefficient between the losses and gains is − 0.97, very close to a perfect correlation of − 1.9

Fig. 2.

COVID-19 job losses and rebound by major industry sector (in millions), February–September 2020

The shutdown affected jobs in four sectors most strongly: leisure and hospitality, retail trade, professional and business services, and healthcare and social services. These are the large sectors, where many employers closed because they were non-essential and had high contact with the public. These sectors accounted for 49% of jobs in February, 69% of jobs lost in March and April, and 75% of the jobs gained from April to September. That is, they suffered disproportionate losses and then rebounded more than proportionally.

Thus, one way to describe the labor market situation as of September 2020 is that the economy has emerged about halfway from the shutdown. At least three factors supported the rebound: relaxation of restrictions after April, slowing of the initial spread of the virus from April to June, and strong relief policies, particularly from the CARES Act and Federal Reserve System policies. The CARES Act’s provisions included issuing checks to most US households, expanding eligibility and generosity of unemployment insurance benefits, and funding retention or recalling of workers by small employers.

The major exceptions to the overall rebound pattern are federal, state and local government jobs. Continued gains in federal government jobs are due largely to temporary hiring for the 2020 Census. Losses in state and local government jobs continued into September, including cuts to public education, health and social services. State and local governments received little support from the CARES Act while their revenues contracted as many expenses rose.

The path ahead will no doubt depend largely on pandemic, policy and recessionary dynamics. If infection rates rise, illnesses, restrictions, and cautious behavior will no doubt constrain economic activity. Policy support from the CARES Act ended in July, so its influence is waning. Along with these factors, large economic shocks like COVID-19 trigger recessionary dynamics. Self-reinforcing widespread uncertainty and economic distress suppresses activity, which fuels more uncertainty and distress, and so on. Consumers and businesses are both affected. Countercyclical policy helped dampen this dynamic early on, but fiscal policy efforts have lapsed for now.

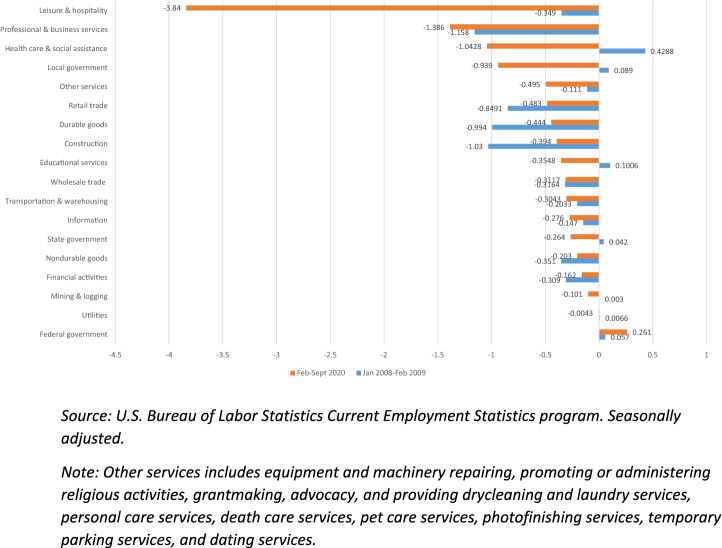

To frame thinking about the path that job losses may take going forward, we can compare current job losses to those during the most recent downturn, the Great Recession. Industrial sectors strongly affected by that downturn are likely to be at risk now as the recession gathers steam. Figure 3 compares COVID-19’s current net job losses (from February to September) to losses sustained from January 2008 to February 2009 (labor market peak to trough)—sorted by the size of current losses. The overall correlation (0.14) between the cycles is positive, but not strong. This is consistent with strong COVID-19-specific job losses and relatively mild recessionary dynamics thus far.

Fig. 3.

COVID-19 February-September job losses (in millions) compared to Great Recession job losses, by major industry sector

COVID-19-specific effects include large losses of education and healthcare and social assistance jobs, which have been largely recession-proof until now. The outsize job losses in leisure and hospitality, other services, and transportation and warehousing also fit into this story. Absent reinstated widespread restrictions, these are areas where further losses are unlikely. Indeed, there is reason to expect more job rebounds.

There is a big risk that rebounds in those sectors will be offset by stronger recessionary influences. What would a deeper recession look like? It would most likely entail further job losses in sectors that lost many jobs during the Great Recession. Consistent with recessionary belt-tightening by consumers and employers, Great Recession job losses were more severe in construction and durable goods manufacturing. Retail jobs could suffer also as the recession would push the least modern, labor-intensive firms out of business. Finally, government employment is likely to shrink. Closing out the 2020 Census will end many temporary federal jobs. State and local jobs normally contract most after the employment trough, when budget shortfalls are highest. Therefore, further losses are likely without federal policy to support the services they provide, including education, hospitals, law enforcement, social services, and more.

Unemployment and job disruptions: share of the workforce with jobs disrupted

Official unemployment rate

The unemployment rate, the other headline indicator from the Employment Situation, tells us the share of the labor force that is unemployed, based on the monthly Current Population Survey of about 60,000 households.10 It also has a long history. In addition, it is never revised (except for minor nudges due to seasonal or population adjustments), provides demographic detail, and covers people who are not on payrolls (that is, those who are self-employed, unemployed or out of the labor force). For these reasons, the unemployment rate is widely referenced in policy decisions, and used to trigger various government funding programs. Its long history, policy relevance, comprehensiveness, and demographic detail are key reasons to track the unemployment rate.

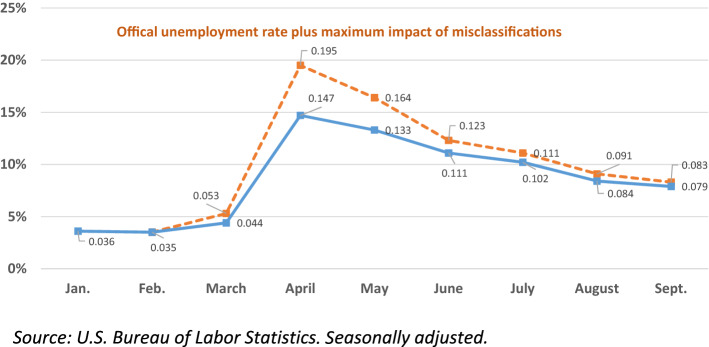

As shown in the solid line in Fig. 4, from February to April shutdowns across the U.S. ballooned the official unemployment rate from 3.5% to 14.7%. The jump of 10.2 percentage points from March to April was historically unprecedented. It also raised unemployment to a post WWII high, almost half again as high as the worst joblessness rate seen during the Great Recession (10%). In May, the unemployment rate began to recede. The first two months reduced the rate to 11.1%, and by September the rate was down to 7.9%.

Fig. 4.

Contrasting unemployment rate estimates, January–September 2020

Yet, there are at least two ways in which the official unemployment rate clearly underestimates the impact of COVID-19 on jobs. The first is due to a data-collection error. The second issue concerns the wide variety of ways that employers and workers responded to the shutdown, not all of which are captured in traditional unemployment. I consider both below.

Misclassifications and the unemployment rate

Since March, BLS has noted that the true unemployment rate is likely higher than the official rate because many workers have been misclassified. Some workers on temporary layoff have responded to survey questions as if they were ‘employed, but not at work.’11 This problem persisted through September, albeit much abated.

Essentially, the category of employed but not at work refers to workers who are away from the job for an employee-initiated reason, such as illness, vacation, family leave, jury duty, national guard service, etc. Employees off work due to pandemic-related shutdowns belong in the category ‘unemployed on temporary layoff.’ They do not need to search for other work to be in this category.

Neither the questions nor the interviewers changed. However, when circumstances changed from anything encountered previously, people responded to the survey in a way that led them to be misclassified. Back in October 2013, the bureau encountered this misclassification problem during the federal government shutdown. Of course, the duration and magnitude of the COVID-19 shock means that this issue is far more consequential now than in 2013 or ever before.

In advance of the March survey, remembering the misclassifications in October 2013, the bureau issued special COVID-19 guidance to the Census Bureau interviewers who field the survey to ensure that temporary layoffs would be properly counted as such.

When the March survey responses arrived, BLS staff checked the data and estimated that as many as 1.4 million workers on furlough may have answered questions as if they were employed but out on some kind of leave. With the benefit of hindsight, this makes sense if many employers and employees had informal arrangements (with no name to call the situation), or agreed to charge the time to some leave category. Many probably had no prior experience with temporary layoffs. Self-employed workers or contractors with no work may also have answered in this way. And, many interviewers may not have seen this situation before.

Before subsequent data collections, BLS transmitted concerns to interviewers, provided more training, and reiterated the previous COVID-19 guidance. No doubt these were received in the midst of many other disruptions during that chaotic time. Unfortunately, the intervention failed to resolve the problem immediately. Employers temporarily laid off a huge share of the workforce in April, and BLS estimates that as many as 7.5 million workers were misclassified.

Each month, BLS has released their estimate of the maximum impact of this misclassification on the unemployment rate. Figure 4 shows these estimates in the red dashed line. The impact of the misclassifications has been consequential in both levels and changes, albeit it has diminished, due to further BLS efforts and improvements in the economy. Most starkly, without misclassification, the unemployment rate in April would have approached 20%, almost double the 10% maximum of the Great Recession, and approaching levels last seen during the Great Depression (often estimated at 25%). BLS’s maximum estimate would put the April unemployment rate at 19.5%, reflecting a total of 31 million unemployed workers.

Despite providing this information, the bureau does not use its misclassification estimates to adjust the official unemployment rate for at least three reasons.

BLS notes that changing respondent answers violates its practices. Changing answers received carries the real risk of setting an unwelcome precedent, putting the BLS at the edge of the proverbial slippery slope. The future could see a rash of recoding demands for less legitimate reasons. In addition, the public could rightfully be less certain that published statistics reflect the underlying data collected.

BLS cannot identify exactly which respondents made the errors. If it were to recode responses, staffers would have to select whose answers to change. So, any recoding would be essentially arbitrary and risk biasing other measures throughout the report, such as detail by race, sex, region, etc. Alternatively, if the agency adjusted the top line without changing underlying microdata, many other statistics would no longer add up to the total properly or be internally consistent.

The BLS method for estimating the impact of misclassifications yields a maximum rather than a best estimate. Official statistics methods are normally subject to rigorous review before they are used in government reports. However, in these circumstances, BLS conducted no cognitive research with respondents, published no papers and consulted no advisory committee. Experienced, world-class professional staff produced useful and credible impact estimates in a short amount of time. But this is not the normal process for producing an official statistic.

So, which unemployment rate should one use, official, or with correction for misclassifications?

Using the official rate is probably the best advice in most cases. This avoids confusion and ensures consistency with local or demographic subgroup unemployment rates, which are not adjusted for misclassification.

However, for the purposes of exercises like this one, it is important to recognize that the official rate understated the severity of the recession for at least 3 months.

Disruptions beyond unemployment

The second reason that the official unemployment rate has understated the labor market impact of COVID-19 concerns the many ways that jobs can be disrupted beyond simple unemployment. A more comprehensive understanding of the impacts on labor input to the economy should reflect these other impacts.

Many of BLS’s regular monthly indicators can be used to track these broader effects. Indeed, other indicators point to large effects, including the following:

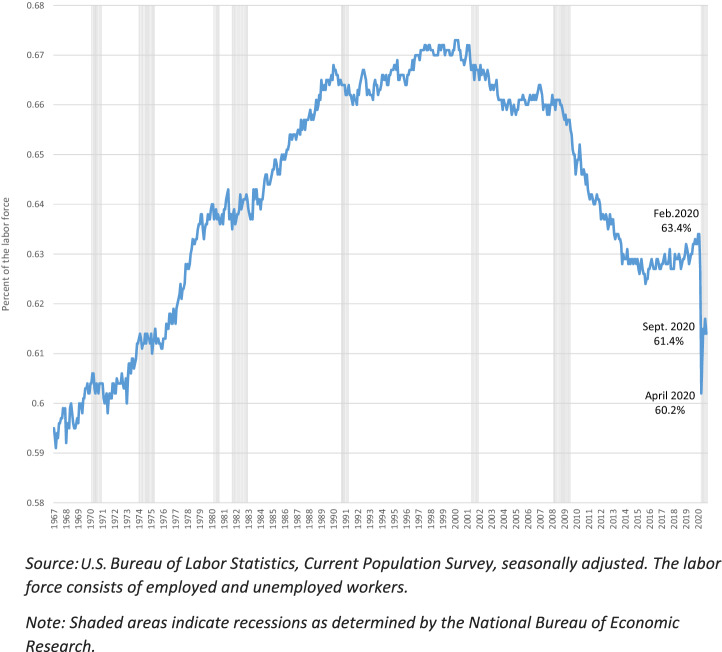

Labor force participation: The pandemic reduced the share of the population (age 16 and over) that was either working or unemployed, at least temporarily. The labor force participation rate (see Fig. 5), which was 63.4% in February, fell to 60.2% in April (the lowest rate since 1972). Although it had rebounded partially to 61.7% by August, it declined to 61.4% in September, led by the exit of women from the labor force, likely in order to care for school-age children during the pandemic. Such exits lower the unemployment rate because they reduce the size of the labor force.

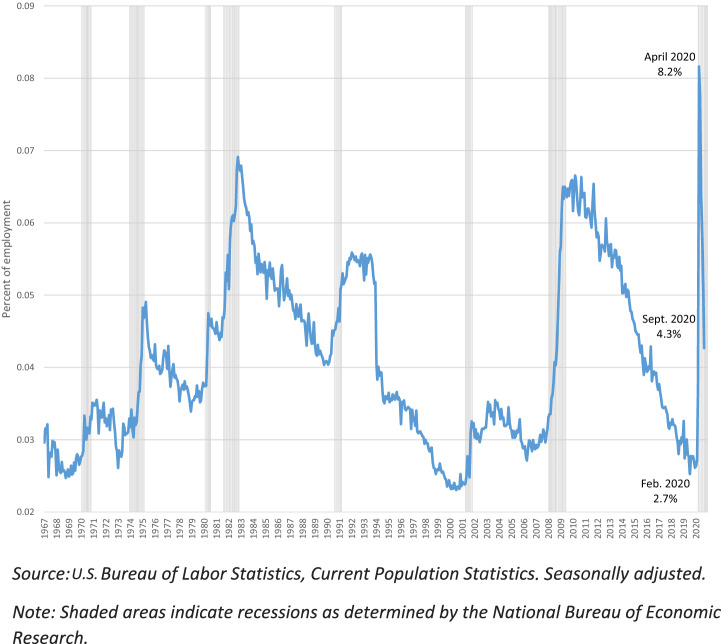

Involuntary part-time work: In addition to cutting jobs, many employers reduced workers’ hours per week in response to COVID-19, as they often do during recessions. This approach retains the connection between employers and workers. An increasing number of states now have Unemployment Insurance “work-sharing” programs that pay benefits to workers whose hours are reduced temporarily, to compensate them for some of their lost wages. The BLS measure of how many people are working part-time for economic reasons (that is, involuntarily) can be seen in Fig. 6. In February, just 2.7% of workers had constrained hours, down from rates about double that during the Great Recession. With the advent of the pandemic, by April, 8.2% of workers were working reduced hours. Interestingly, this share has rebounded more than many other labor market indicators and stood at 4.3% as of September (Fig. 5).

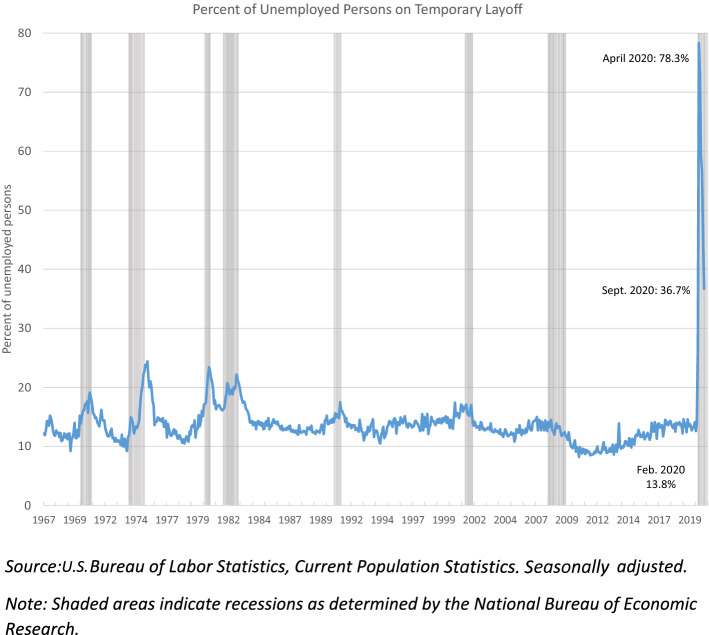

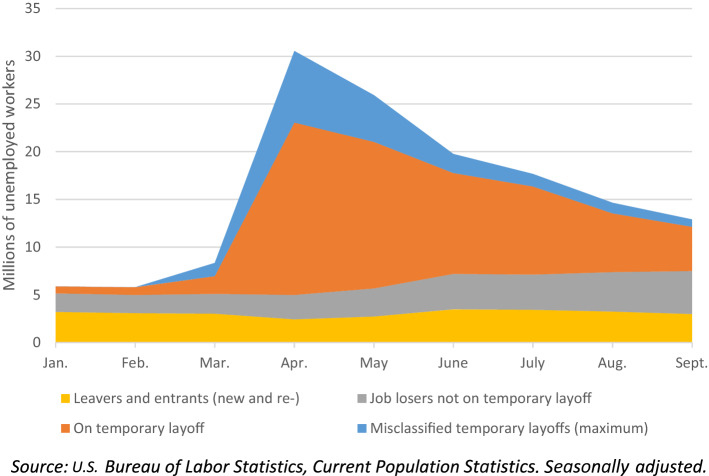

Temporary furloughs versus permanent layoffs: One of many signs of the exceptional nature of the COVID-19 shock was how much of the job loss was due to temporary layoffs. In April, the share of all unemployed workers on temporary layoff leaped to a historically unprecedented 78.3%, compared to 13.8% in February (see Fig. 7). Even as of September, the share was still very high, at 36.7%, well above the previous peak of 24% in June 1975. This really matters for our eventual recovery from this recession. While furloughs are signals of employer distress and cause hardship for workers, they have some clear advantages over permanent layoffs for workers, employers, and the speed of economic recoveries. In the past, most workers on temporary layoff have been recalled to their former jobs. When they are, they can show up for work and be immediately productive because there’s no need for job search, recruitment, background checks, onboarding, training, getting to know teammates, etc. No firm-specific knowledge is lost. Furthermore, while they await recall, workers likely will not delay as much consumption as if they faced the greater uncertainty of needing to find a new job. By the same token, employers are spared the uncertainties of getting the skilled workforce they need, so they can make the purchases they need to be ready to start up again. For reasons not clearly established, during the last three recessions, employers made mostly permanent layoffs (as seen in Fig. 7). This new tendency toward permanent layoffs no doubt contributed to the recent “jobless” recoveries so apparent in Fig. 1. In stark contrast, the key reason the labor market could rebound as quickly as it did from May to August was the high rate of temporary furloughs rather than permanent layoffs in March and April. Figure 8 shows how the composition of unemployed workers has changed from January to September, including the potentially misclassified workers. Clearly the first two months saw a dramatic jump in temporary layoffs, which are now declining, while traditional unemployment rises.

Fig. 5.

Percent of the population participating in the labor force

Fig. 6.

Percent of employed persons working part-time involuntarily (“for economic reasons”)

Fig. 7.

Percent of unemployed persons on temporary layoff

Fig. 8.

Unemployed workers on temporary layoff or not, January–September 2020

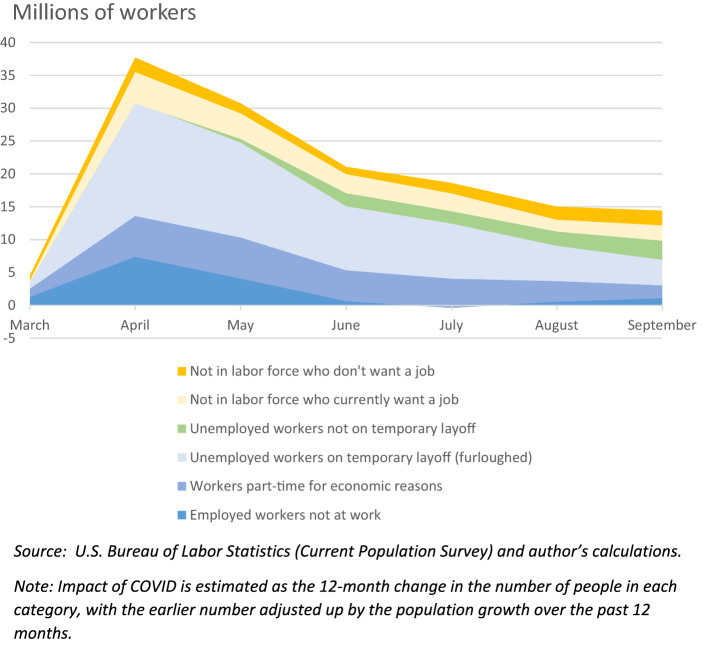

To move beyond the unemployment rate to a broader handle on the labor market effects of COVID-19, we can combine indicators that reflect the issues noted above. This will be a measure of disruptions, not unemployment, because some disrupted workers are employed—albeit less well than before (that is, those who are on leave or short hours) and other disrupted workers have left the labor force. Note that this is a marginal measure; it compares conditions to those prevailing before the pandemic. We are intentionally excluding the “normal” or pre-COVID-19 amount of distressed workers.

To help judge prospects going forward, we can divide disrupted jobs between those where the workers remain connected to their employers, and those where the tie is severed. To estimate the impact of the pandemic, we compare each month’s numbers with those for 12 months ago. This takes care of seasonal effects. To account for population growth, we adjust the numbers from 12 months ago by population growth during that time. Then, we add up all of changes in the following indicators:

Employed workers not at work: Workers on leave from their employer, whether paid or not (for illness, family reasons, vacation, etc.)

Workers part-time for economic reasons: Workers who prefer to work full-time but only found a part-time job, or who usually work full-time but had their hours reduced by their employer

Unemployed workers on temporary layoff (furloughed): Laid-off workers who expect a recall within 6 months

Unemployed workers not on temporary layoff: Includes workers permanently laid off, new and re-entrants and job leavers

People out of the labor force who currently want a job: People without a job who are not looking for work but say they want a job

People out of the labor force who do not want a job: Largely students, retirees, and people with disabilities or caring for family members

The first three categories capture workers whose relationships with an employer are intact despite disruptions, in contrast to the latter three. Table 1 and Fig. 9 present the results of this exercise.

February to April downturn: The first column of Table 1 shows that by this metric the pandemic was disrupting 37.7 million workers’ jobs in April. Non-temporary-layoff unemployment was essentially unchanged. All the disruptions flowed into other categories, reflecting employers’, workers’ and policy choices. About 6.8 million of the disrupted group no longer had a connection to an employer, while 30.9 million still did. The last row shows that April’s disruptions affected 23.1% of the pre-COVID labor force. If we add this percentage to the official unemployment rate in February (3.5%) we get that as of April, 26.6% of the labor force faced serious job disruptions. If we go beyond unemployment to include the impact on labor force exit, leaves from work and reductions in hours, more than a quarter of the US labor force were experiencing a serious disruption in their job in April.

April to September rebound: Figure 9 traces the path of disruptions from March to September. As in the other measures shown earlier, May and June showed strong improvements, and the pace has slowed since then. Furthermore, the composition of disruptions has changed markedly. The largest decline was in workers on temporary layoff (from 17.3 million to 3.9 million). This reflects both the recalling of workers from temporary layoff (an encouraging reason) or the conversion of temporary layoffs to permanent ones (a concerning reason). Most of the other categories also showed improvement, with two exceptions: those unemployed not on temporary layoff (which increased) and those not in the labor force who do not want a job (which was unchanged). The figure also shows that the pace of improvement has slowed substantially since May.

Status as of September: The third and fourth columns of Table 1 show that, by mid-September, COVID-19 was still disrupting the jobs of 14.4 million workers, or about 9% of the labor force. Only 6.8 million (less than half) of those workers are classified officially as unemployed. Thus focusing solely on changes in the unemployment rate understates the severity of the disruptions caused by COVID-19. Once again, if we add this to a pre-COVID unemployment rate of 3.5%, the total rate is over 12%. Over time, though, an increasing number of the COVID-19 job disruptions are in the category of traditional unemployment. It is concerning that, while there are many fewer disrupted workers who are connected to an employer, the number without a connection has actually risen from 6.8 million to 7.5 million. In addition, the stability of the intentions of workers out of the labor force as the result of COVID-19 who do not want a job suggests potential trouble. It suggest that we could face a long-term decline in labor force participation going forward.

Table 1.

How COVID-19 labor market disruptions are distributed

| As of April 2020 | As of September 2020 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Millions of disrupted workers | Share of disrupted workers (%) | Millions of disrupted workers | Share of disrupted workers (%) | |

| Category of job disruption | ||||

| Employed workers not at work | 7.4 | 20 | 1.1 | 8 |

| Workers part-time for economic reasons | 6.2 | 16 | 1.9 | 14 |

| Unemployed workers on temporary layoff (furloughed) | 17.3 | 46 | 3.9 | 27 |

| Unemployed workers not on temporary layoff | − 0.2 | − 1 | 2.9 | 20 |

| Not in labor force who currently want a job | 4.8 | 13 | 2.3 | 16 |

| Not in labor force who don't want a job | 2.2 | 6 | 2.2 | 16 |

| Disrupted workers connected to employer | 30.9 | 82 | 6.9 | 48 |

| Disrupted workers without connection to employer | 6.8 | 18 | 7.5 | 52 |

| Total disrupted workers | 37.7 | 100 | 14.4 | 100 |

| Total disrupted workers as a share of pre-COVID labor forcea | 23% | 9% | ||

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (Current Population Survey) and author’s calculations. Disrupted workers are estimated as the 12-month change in the category (NSA), where the number from 12 months ago is multiplied by the percent increase in population (age 16 +) over the last 12 months

aFor each month, the pre-COVID labor force is estimated as the labor force 12 months ago (SA) multiplied by the percent increase in population (age 16 +) over the last 12 months

Fig. 9.

COVID-19 labor market disruptions, March-September 2020

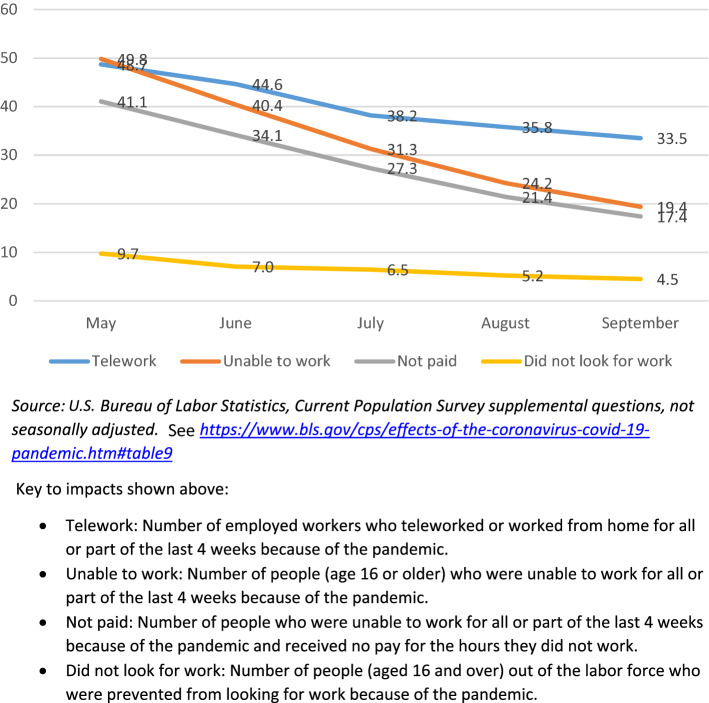

Recovery from disruptions, using CPS special questions

Starting in May, BLS added a set of special COVID-19 questions to the CPS to aid in judging broader pandemic impacts. The questions yield the following monthly estimates, shown in Fig. 10:

Telework: Number of employed workers who teleworked or worked from home for all or part of the last 4 weeks because of the pandemic.

Unable to work: Number of people (age 16 or older) who were unable to work for all or part of the last 4 weeks because of the pandemic.

Not paid: Number of people who were unable to work for all or part of the last 4 weeks because of the pandemic and received no pay for the hours they did not work.

Did not look for work: Number of people (aged 16 and over) out of the labor force who were prevented from looking for work because of the pandemic.

Fig. 10.

COVID-19 impacts on telework, lack of work and ability to look for work (in millions), May-September 2020

Overall, these results show the wide impacts of COVID-19. They remain high, even though they have been declining since April. Two of these indicators (inability to work or look for work because of COVID) also support the estimates of impact listed in the previous section.

The most persistent and largest impact has been a transition to telework or work from home—as seen in Fig. 10. In May, almost 50 million US workers (close to a third of the February labor force) teleworked or otherwise worked from home because of the pandemic, for at least some part of the month. By September, this number had fallen by about a third. For most involved, this was likely the most benign outcome. Nevertheless, for some the change imposed difficulties, particularly in the short run.

In May the pandemic rendered a similar number of workers (almost 50 million–also close to one third of the pre-COVID-19 workforce) unable to work at all for at least some part of the month. By September, the number was about 19 million, down by three-fifths. Most of these workers were not paid for hours not worked, as can be seen in the gray line. The share paid has been fairly stable, in the range between 8 and 9% (Fig. 10).

The lowest line shows the number of workers prevented from searching for work because of COVID-19. From May to September, this declined by more than half from almost 10 million to 4.5 million. For BLS to count someone as unemployed, they must have looked for work during the past month or be temporarily laid off. This is consistent with the story that a large number of workers lost jobs permanently early on, but were unable to search for new work right away. Thus, they were counted as having exited the labor force, rather than as unemployed. Only the newly furloughed workers added to the ranks of the unemployed in the first two months. Since then, more sidelined workers have been able to search and reenter the labor force.

In short, the COVID-19 special questions help round out our understanding of the rebound period. Telework shot up and is declining quite slowly. Inability to work was very high but has declined by three-fifths; less one in ten of these workers are paid for work-time lost. Many jobless workers cannot search for work because of the pandemic, so suppressed labor force participation is an important part of the pandemic’s impact on the labor market.

Who has been affected most?

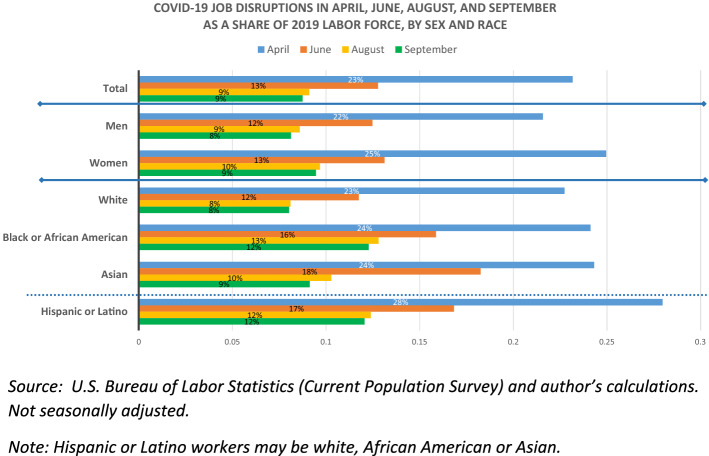

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the work of U.S. workers unequally. This section examines disparities in how those job disruptions affected men versus women, white workers versus African American, Asian, and Hispanic workers.

Male and white workers continue to fare better than female, African American, Asian, and Hispanic workers. By faring better, I mean both that fewer jobs have been disrupted and/or that more workers whose jobs have been disrupted retain a tie to an employer.

Figure 11 shows the share of the labor force with disrupted jobs in April, June, August and September. Note that I do not have standard errors for these estimates. Small differences, particularly for the smaller population segments, could easily be due to sampling error.

The top set of bars in Fig. 11 show the share disrupted by months noted for the entire labor force. As we saw above, in September, COVID-19 was still disrupting the jobs of nine percent of the U.S. labor force, a substantial decrease from the 23% of jobs disrupted in April.

The next sets of bars in Fig. 11 repeat the exercise separately for men and women. By April, women’s jobs were more disrupted by COVID-19 than men’s jobs. Improvements since then have narrowed the gap.

Continuing down the figure, jobs held by white workers have been less disrupted than jobs held by African American or Hispanic workers, and they recovered faster between April and June. White and Asian workers saw about the same improvement from April to September.

-

African American and Hispanic worker have seen much less improvement in disruptions than white workers. Along with high death rates from COVID-19, these two groups of American workers have seen particularly dire labor market impacts from COVID-19.12

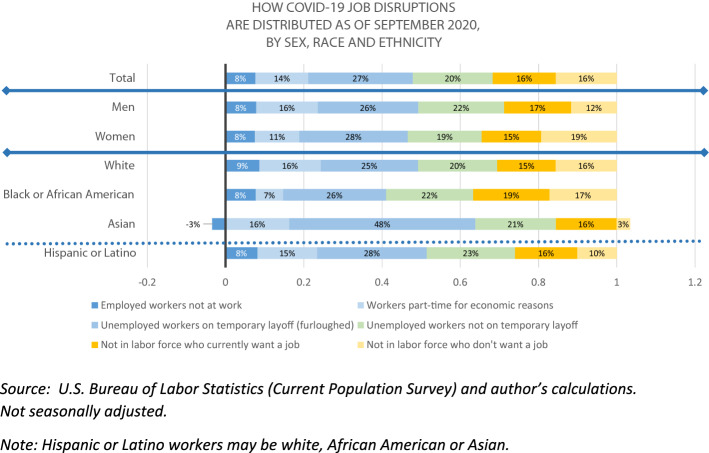

Figure 12 shows how each group’s job disruptions are distributed as of September 2020. The percentages shown are each type’s disruption as a share of all disruptions for the group. The disruptions that preserve the relationship between worker and employer are shown in the bottom three sections of each bar. The most striking difference is that more disrupted women and African-American workers have left the labor force than is true of the other demographic groups.

As of September, women workers have the highest share of disruptions in the form of leaving the labor force and reporting that they do not want a job. This is consistent with expanded childcare and family responsibilities because of the pandemic.

The share of disrupted African American workers retaining a tie to an employer is the smallest (only 41%) of any group. The share of disrupted African American workers who want a job, but who have not actively looked for work yet (nineteen percent), is the highest of all the demographic groups. This suggests the presence of continuing barriers to job searches for this group.

Asian workers have the smallest share (19%) of disrupted workers who have left the labor force and the largest share (48%) on temporary furloughs, which explains their high percentage of workers with continuing ties to employers.

Hispanic workers’ distribution of disruptions is quite similar to the overall distribution, even though, as noted above, the share of Hispanic workers disrupted is higher than average.

Fig. 11.

Race and sex disparities in COVID-19 job disruptions in April, June, August and September 2020 as a share of the labor force

Fig. 12.

Race and sex disparities in how COVID-19 job disruptions are distributed, September 2020

Conclusion

In sum, COVID-19 has affected the U.S. labor market in the following ways:

The initial shock was very abrupt and deep by all historical standards. About 15% of payroll jobs (22 million) were lost in March and April. Despite recovery of about half of the payroll jobs lost by September, labor market conditions remain dire. Indeed, looking only at changes in payroll jobs and unemployment understates the scale of COVID-19 job disruptions substantially. A broader look indicates that COVID-19 disruptions affected more than a quarter of the US labor force in April. Particularly at the outset, more workers entered other disrupted states (employed but away from work, involuntary part-time and out of the labor force) than joined the ranks of the officially unemployed. Beyond that, many workers switched work locations. In May, close to 50 million workers (almost a third of the pre-COVID labor force) worked remotely at least part-time as a consequence of COVID-19.

The pace of the jobs recovery has slowed markedly since June. This likely reflects fewer business reopenings, some reversals, along with mounting recessionary influences (from bankruptcies, delinquencies and cautionary behavior on the part of consumers, state and local governments, companies and investors).

The share of disrupted workers who have maintained relationships with employers, which began very high, is declining, dimming prospects for further rapid recovery. Now, in contrast to April (when only a fifth of disrupted workers were disconnected from their employers), more than half of the workers whose jobs are disrupted have been cut loose permanently; they are either searching for a new job or have left the labor force.

The jobs of Hispanic, African American and women workers are more disrupted than others. Women and African American workers have exited the labor force disproportionately. This could be a signal of a troubling long-term decline in labor force participation due to the pandemic.

Going forward, what will the recovery and the post-COVID labor market look like? Without quantifying the effects, we can list the key forces that will interact to shape the path going forward. Two influences will be temporary and two more permanent, all of which can mitigated at least partially by policy.

Pandemic-related restraints and resumptions: These will cause uncertainty, constrain the recovery, and persist to some degree until the virus is contained. Policy can help speed the search for ways to protect lives at least cost to wellbeing. This includes supporting health research and the development and distribution of a vaccine, and all the steps to protect and support the population until there is sufficient immunity.

Business cycle dynamics: COVID-19 has shocked the economy, triggering well-known national and global recessionary dynamics. Loss of confidence in business conditions going forward causes belt-tightening, which further slows growth and future prospects, etc. These effects, which are only now growing stronger, can be mitigated by countercyclical policy monetary and fiscal policy.

Ongoing structural changes: Recessions tend to speed the pace of structural changes in response to new technologies, trade pressures, and consumption trends. Workforce development policy can ease workers’ adjustments to these changes.

COVID-19-related adaptations that persist beyond the pandemic: The experience of the pandemic will likely change trends for some of all of the following: home-schooling, retirement age, telework, online shopping, congregate living arrangements, urban real estate, business and leisure travel, scientific research, and more.

When the virus is under control, will we have another long jobless recovery, like that after the Great Recession? The paths of recent recoveries suggest that the answer may be yes. Over the coming months, recessionary forces are likely to gather steam, causing further job losses in sectors such as construction and durable goods manufacturing, retail jobs, and government. If so, we might expect six years or more before we return to the employment level we had in February 2020. And, of course, getting the pandemic under control may take another year or so. That could mean a long path to recovery.

On the other hand, policy lessons from the last downturn may help policymakers to avoid a prolonged recovery. The Federal Reserve’s monetary response has been very rapid and robust so far. Early in the year, fiscal policymakers seemed poised to follow suit with fiscal actions stronger than those enacted early during the Great Recession. However, the support from the CARES Act is largely exhausted with no follow-up in sight. Instead of withdrawing support, there is room for fiscal policy to take a stronger hand this time to help speed the recovery—supporting consumption, investment and provision of services to disadvantaged populations. If we take those actions, we have an opportunity to achieve a faster recovery than we did during the most recent recessions and keep more of our workers in the labor force.

Thus, the prospects for a speedy jobs recovery is most likely to depend on two key factors—the path of the pandemic (including the success of public health policy) and the robustness of fiscal stimulus for the economy.

Another more subtle contributor to a robust recovery will be gold-standard official statistics to guide policymakers, investors, companies, researchers, and families as they make critical decisions. COVID-19 has lessons for this important public good as well. First, it demonstrates once again that official statistics are essential public infrastructure. For example, no other source of labor market information was broad and authoritative enough to have alerted observers to May’s rebound before the jobs report came out. Public dollars invested in official statistics have a large payoff. Second, producing gold-standard statistics is difficult, especially during extraordinary times. BLS, in particular, deserves high praise for perseverance and innovation during this critical time. It dealt transparently and authoritatively with issues such as response rates and misclassification. Even during an extreme shock, BLS accurately collected, processed and vetted huge amounts of data on its usual tight timeframe. Third, public trust in official statistics matters. Fortunately, the practices that preserve the BLS independence and data integrity have served it well during the COVID-19 crisis and helped to direct societal attention to important labor market issues. Strengthening our national statistical agencies’ resources and independence will be critical to help our country recover from this shock and to prepare for the next one.

Erica L. Groshen

is Senior Labor Economics Advisor at Cornell University—ILR, Research Fellow at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, and serves as a member of the Federal Economic Statistics Advisory Council and the Committee on National Statistics of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine. From 2013 to 2017, she served as 14th Commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the principal federal agency responsible for measuring labor market activity, working conditions, and inflation. Before that she was Vice President in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Her research centers on employers’ roles in labor market outcomes. She coedited Improving Employment and Earnings in Twenty-First Century Labor Markets, from RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Science, co-authored How New is the “New Employment Contract”? from W.E. Upjohn Institute Press and co-edited Structural Changes in U.S. Labor Markets: Causes and Consequences, from M.E. Sharpe, Inc. Dr. Groshen received the 2017 Susan C. Eaton Outstanding Scholar-Practitioner Award from the Labor and Employment Relations Association and was appointed a Fellow of the American Statistical Association in 2020. She holds a Ph.D. in economics from Harvard University and a B.S. in mathematics and economics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Footnotes

For more detail, see https://www.bls.gov/bls/data_integrity.htm.

For more information, see https://www.bls.gov/bls/infohome.htm.

For more information, see https://www.bls.gov/ces/publications/benchmark/ces-benchmark-revision-2009.pdf.

For more information, see https://www.bls.gov/ces/notices/2020/birth-death-notice.htm and https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cesbd.htm.

For more information, see https://www.bls.gov/osmr/response-rates/.

For more information, see https://www.bls.gov/covid19/effects-of-covid-19-pandemic-and-response-on-the-employment-situation-news-release.htm.

For information on the Current Employment Statistics Program, see https://www.bls.gov/ces/.

Since no single method can answer all questions, it is also important to understand the limitations of this approach. First, the number of jobs on payrolls misses some important labor market complexities. For example, it does not take factor in self-employed workers, or adjust for hours worked or earnings. Second, as we add up jobs all across the country, we do not consider that impacts will often differ substantially by geography or demographics. So, we are not looking at inequality of any sort. Third, by looking at the total number of jobs we take no account of dynamics or churning (that is, how much job creation and destruction underlies the smaller net change). Fourth, we are not looking directly at how much of the value created by these workers has been lost or restored. Fifth, we have not adjusted for the growth in jobs that would have occurred in the absence of the recession. Thus, the time to recovery shown here is underestimated by the extra time it would take to return to a long-term trend. This is particularly important for deep recessions with slow recoveries, as is likely in this case.

The relative sizes of these sectors plays some role, but the correlation coefficient between losses and gains expressed as percentages of February employment is only slightly smaller: − 0.84.

For more information about the Current Population Survey, see https://www.bls.gov/cps/.

For the BLS description of the misclassification problem see https://beta.bls.gov/labs/blogs/2020/06/29/update-on-the-misclassification-that-affected-the-unemployment-rate/. Also see https://www.ilr.cornell.edu/work-and-coronavirus/work-and-jobs/will-true-unemployment-rate-please-stand.

Seehttps://www.statnews.com/2020/06/15/whos-dying-of-covid19-look-to-social-factors-like-race/?utm_source=STAT+Newsletters&utm_campaign=cb569725ae-Daily_Recap&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_8cab1d7961-cb569725ae-152361770 and https://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e2externalicon.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.