Abstract

The spatial template over which COVID-19 infections operate is a result of nested societal decisions involving complex political and epidemiological processes at a broad range of spatial scales. It is characterized by ‘hotspots’ of high infections interspersed within regions where infections are sporadic to absent. In this work, the sparseness of COVID-19 infections and their time variations were analyzed across the US at scales ranging from 10 km (county scale) to 2600 km (continental scale). It was found that COVID-19 cases are multi-scaling with a multifractality kernel that monotonically approached that of the underlying population. The spatial correlation of infections between counties increased rapidly in March 2020; that rise continued but at a slower pace subsequently, trending towards the spatial correlation of the population agglomeration. This shows that the disease had already spread across the USA in early March such that travel restriction thereafter (starting on March 15th 2020) had minor impact on the subsequent spatial propagation of COVID-19. The ramifications of targeted interventions on spatial patterns of new infections were explored using the epidemiological susceptible-infectious-recovered (SIR) model mapped onto the population agglomeration template. These revealed that re-opening rural areas would have a smaller impact on the spread and evolution of the disease than re-opening urban (dense) centers which would disturb the system for months. This study provided a novel way for interpreting the spatial spread of COVID-19, along with a practical approach (multifractals/SIR/spectral slope) that could be employed to capture the variability and intermittency at all scales while maintaining the spatial structure.

Keywords: COVID-19, Multifractality, Spectral analysis, Susceptible-infectious-recovered (SIR) model, Population agglomeration, Scaling

1. Introduction

The spread of COVID-19 has occurred over the whole globe with impact from the individual to the world. The spatial spreading and temporal evolution of the number of cases is a complex process that involves various sectors and individuals. The dynamic data dashboards demonstrated spatial heterogeneity in the infected cases and deaths caused by Covid-19 over a wide range of scales [41], [44]. Therefore, studies on the Covid-19 pandemic from a spatial perspective is critical to better understand the nationwide spread of disease. The spatial distribution of infections is also “patchy” and intermittent (Fig. 1 a and 1b), especially at the smaller scale (Fig. 1c). This is a unique signature of multifractal fields, such as the velocity fluctuations in turbulent flows [10], rainfall [39], [13], and soil properties [3], [9], [45]. In addition, the number of cases changed over time, with the total number of cases increasing from 0 to a million within six weeks (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

Contours of observed COVID-19 cases in the USA on (a) March 23rd 2020 and (b) May 5th 2020. (c) Bar graph of the Washington DC area (for illustration). (d) Simulated number of total cases using the parameter values of the Universal Multifractal model on May 5th 2020 (α = 1.7; c1 = 0.3; H = 0.3). (e) Number of passengers (https://www.tsa.gov/coronavirus/passenger-throughput) and number of COVID-19 cases starting from March 1st 2020 reflecting the effects of ‘shut-down’ in air travel, and consequently long-distance transport of COVID-19.

The evolution of the number of cases of diseases over time has been well captured using epidemiological models, which have been developed and widely used for characterizing the dynamics of the spread of infectious diseases since the seminal work of the Bernoulli (of the Bernoulli equation) [8], and expanded during 1920s for understanding disease transmission and for planning effective control strategies [19], [20], [37], [7], [18], [34]. A well-known approach is to use epidemic compartment models such as the susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) model [2], [6], [11]. The SIR model classifies individuals in the compartment as one of three classes: susceptible (S), infectious (I), and recovered or removed (R), which can be implemented using either a deterministic approach or a stochastic approach by incorporating, for example, a stochastic reaction–diffusion process [34].

Modeling efforts of the COVID-19 spread have started with short papers published in March 2020 [1], [12] including simplified fractal models [49]. These works have synthesized data of China COVID-19, but they relied on fitting a time series (at a location) the data. Detailed models known as agent-based network models, allow for travel between locations, and they have been used to model the spread of COVID-19 in China and Italy [5], [26]. A empirical analytical model adopted by the University of Washington is commonly discussed in the news [15]. These models are regularly recalibrated to better reproduce the data. In addition, some of them are designed to represent COVID-19 data at the continental scale and/or based on large metropolitan areas. As the scale decreases to below 100 km (e.g., at the county scale), these models could become unwieldy because the connectivity is proportional to the square number of communities. In addition, some of the data (of travelers) might not available, and there are societal concerns with the usage of individual information. Furthermore, as the number of connections increases, the problem could become ill-posed, whereby many combinations of values produce the same results (equifinality problem). One could also argue that even when fitting to data, the metric for the fitting would impact the prediction. For example, if the fitting emphasized matching large values (i.e., large cities), the prediction of the model is likely to be poor for small cities. Conversely, if the fitting is normalized by the population, then model prediction of the total number of cases might be poor (but good when normalized by the corresponding population).

While not fully solving the dilemma of multiple objectives, our approach provides a “regularization” [38] for these models using the constraint that the data are multifractal, reasonably captured using the multifractality class (represented by the parameter of the UM model discussed below), and the spatial structure (represented by the spectral slope) of the infection. Simulations of COVID-19 case numbers that do not maintain these constraints imposed by the kernel of the data could fluctuate wildly with time, and are not reliable.

The goals of the current manuscript are: 1) analyze the COVID-19 cases at the level of US counties over time using the multifractal approach, 2) estimate the parameter values of the SIR model as applied to US counties, 3) develop an SIR/multifractal approach that captures the heterogeneity of the data and its time evolution and 4) explore scenarios of re-opening either rural or urban areas (without determining the actual location).

2. Methodology

2.1. Multifractals

Multifractality occurs when the exceedance probability (Pr) of a field, Gc, such as the total number of infectious cases, scales according to where is the scale ratio (ratio of large scale to the scale of observation), is the order of singularity (a positive quantity), ~ implies proportionality within slowly changing quantities such as Ln [29]. The term is the codimension of the field, and is an increasing function of [14], [39]. As increases, the probability of exceedance of decreases. This is intuitive, and captured by a decrease in the fractal dimension of the set indexed by , where N is the Euclidian dimension of space (=2 for infections in a 2D plane). While the multifractal properties can be estimated based on the exceedance probability [25], it is easier (and more reliable) to use the statistical moments of the field at various scales , , which can be obtained from the exceedance probability using the Legendre transform [10], [29]. Note that brackets imply ensemble averaging and the value of Gc at scales larger than the smallest scale of observation is obtained by coarsening the field through averaging [24], [3]. Then, if Gc is multifractal, its moments satisfy:

| (1) |

where K(q) is the moment scaling function and is nonlinear convex (i.e., upward looking) if the field is multifractal. For monofractal fields, K(q) is a linear function of q. The usage of various q values is needed because the probability density function of Gc is not known, and thus one varies q to obtain different information on the field Gc. For example, q = 1 gives information on the mean value of the field; large q values provide information on the large values in the field (as it magnifies the large values), while q < 1 provides information on the small values in the field. Some studies used also negative q values to further magnify (and subsequently analyze) the small values in the field (for better quantification), but this is not going to be considered herein.

The usage of a model allows realizations to be generated that could be used for further scrutiny of policy interventions and public health measures. Multiplicative cascades are the prominent approach for generating multifractals, and various statistical distributions have been adopted for the sub-generator (i.e., the logarithm of the field), including Gaussian [48], binomial [28], and Poisson [42]. A generalization of the Gaussian to Levy-stable was adopted for turbulence [39], [21] and for quark-gluon plasma phase transition [4]. This generalization was expanded on by Schertzer and Lovejoy [28], who developed the Universal Multifractal (UM) model, which is adopted here. The UM model yields:

| (2) |

where α is the multifractality parameter (), representing the underlying statistics of Ln Gc fields. The Ln Gc field is only Gaussian when , and smaller values produce α-stable probability distributions [33]. As decreases the field becomes more “spotty” and the large values tend to be clumped together. The parameter c1 is the codimension of the mean field, and is equal to half of the variance for and plays a similar role for other values.

Many fields, G, exhibit scaling of the type [39]:

| (3) |

that is, they are obtained from the fields Gc by a fractional integration of order H, where H is a parameter that represents the redistribution of singularities with an average shift of -H. The H is sometimes known as the Hurst coefficient, and was found to be 1/3 for turbulence velocity increments [17] in agreement with the −5/3 spectral exponent from Kolmogorov’s theory in the absence of intermittency corrections [31]. Fields with H = 0 are known as conservative fields, because the mean value does not change with scale [27] (hence, the index “c”).

The Fourier spectrum of the field G (Eq. (3)), E G, has a power law form:

| (4) |

where k is the wave number in Fourier space, and β is labelled as the “slope”, as it would be the slope in a log–log plot of vs . For multifractal fields:

| (5) |

where K(2) represents the intermittency of the data (discussed below). The value of H represents also the “distance” to conservative multifractals. It is equal to 0 for the kinetic energy dissipation rate [10]. It is equal to 1/3 for the velocity fluctuations in turbulent flow fields [29], and becomes an empirical coefficient for other geophysical fields such groundwater permeability [45] and rain [46].

The multifractal scaling properties were analyzed for the number of daily COVID-19 cases in the US counties from 23rd March 2020 to 7th May 2020. The eastern part of the US (east of 100° W) was selected to analyze multifractal scaling properties at relatively small scale (i.e., 10 km). The moments, moment scaling function K(q), and power spectral density of daily total confirmed cases were computed at a sample spacing of 10 km along the east–west and north–south directions, respectively. Similar patterns were observed in both directions, and thus, isotropy was assumed to explore daily multifractal scaling properties of spatial COVID-19 spreading. The spatial multifractal properties were also analyzed for the total population in corresponding eastern part of the US. The data of daily COVID-19 cases were acquired from Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resources Center (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu) last interrogated on May 07, 2020. The multifractal scaling properties of the corresponding county population were also obtained based on data acquired from the United States Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/data.html). To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze multifractal scaling properties of COVID-19 cases, and incorporate such properties into the SIR modeling.

2.2. Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered (SIR) model

The dynamical system describing the SIR equations subject to mass action mixing is given as [16]:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

where S is the number of susceptibles, I is the number of infected, and R is the number of removed (healed or dead). The term N is the total population in a particular location, and is thus N = S + I + R. In the current investigation, N is taken as time invariant, as we are not accounting for travel into and out of the region of interest. The terms and are known as the transition rates of infection and recovery, respectively; is the force of infection, and is expressed as R 0, defined as the basic reproduction number, representing the average number of secondary infections caused by a primary case. The term R 0, called reproduction number, is probably the most important parameter in the SIR model. A value of R 0 smaller than 1.0 indicates that the disease does not spread and large R 0 values reflect high infectivity. Values of R 0 vary from 0.5 for SARS [22] to 9.2 for measles [23]. The COVID-19 R 0 values range from 2.0 to 7.0.

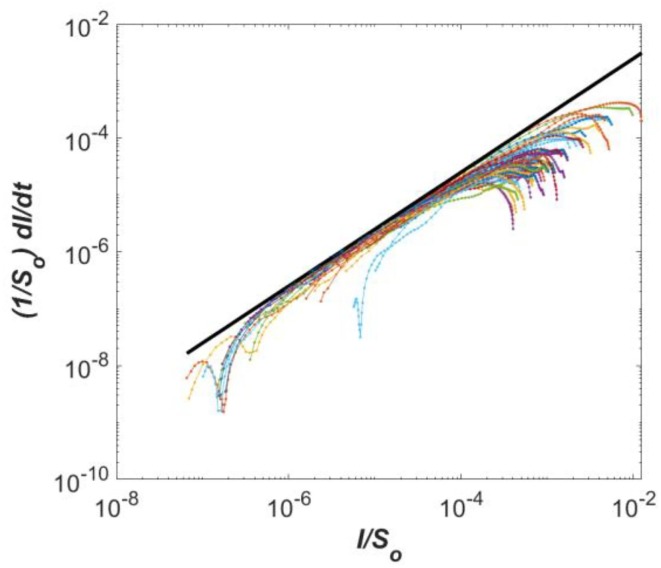

The simulation period of the SIR model in this work was 200 days from March 10th, 2020 through Sep. 25th, 2020. The model calculations assume that counties are isolated ‘compartments’ in agreement with the effective travel restriction in mid-March 2020 (Fig. 1e), with susceptibles, infected, and removed interacting using mass action mixing within each county. The SIR model predicts the time evolution of infections in each county based on the local population and two externally supplied epidemiological parameters: the basic reproduction number (R 0) and the mean duration of recovery . The value of R 0 from March 10th through March 30th, was estimated from all US States using the approach of applied at the beginning of the pandemic on worldwide data. The approach relies on plotting as function of in log–log scale. A straight-line behavior provides the value of R 0-1, and thus one extracts Ro.

Fig. 2 shows that R 0 ≈4.5 from March 10 through March 30th 2020. This value was reduced to 2.0 starting April 2020 to reflect curfews and local distancing, which is commensurate with values reported for South Korea initially after social distancing was implemented there [43]. The parameter is generally interpreted as the inverse of the mean recovery time D. For COVID-19, the best information on the speed of recovery is derived from a World Health Organization study examining more than 55,000 cases in China. It found that for mild illnesses, the time from the onset of symptoms to natural recovery is, on average, 2 weeks (i.e., D = 14 days). The initial infectious population Io was assumed maximally 1% of So, which is expressed as Ru × 1% × So, where Ru is a uniformly distributed random number between 0 and 1. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using Ro ± 0.5 during the first 20-day and Io ± 50%.

Fig. 2.

(1/So)(dI/dt) as a function of I/So for all US states (New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/article/coronavirus-county-data-us.html, accessed on May 7th 2020). The fitted slope is estimated to be 3.5, which is equal to (Ro −1). Therefore, the value of Ro is estimated to be 4.5.

The multifractal properties of the population were used to generate the number of the susceptibles in the SIR model. This was done by generating multifractal fields, based on the UM model which gives continuous cascades [39], [35]. The generated fields were obtained over 512 × 512 cells each of size 10 km × 10 km resolution. Then, the central 256 × 256 cells were extracted and used for epidemic modeling using the SIR (susceptible, infected, removed) model.

Simulations were also conducted to explore potential scenarios of re-opening of rural and urban areas after May 15th, 2020. For these simulations, rural and urban areas were selected from the simulated domain through a threshold of the population, less than 20th percentile and larger than 80th percentile, respectively. The re-opening is implemented by adjusting Ro of the selected regions from 2.0 to 4.5 on May 15th, 2020. The value = 1/14 d−1 was unaltered.

3. Results

3.1. Multifractal analysis

The statistical moments of a multifractal field are generally summarized by the moment scaling function, K(q), which is a convex (upward facing) function of the analyzing statistical moment q reflecting the fact that large values of the field change faster with scale than those close to the mean.

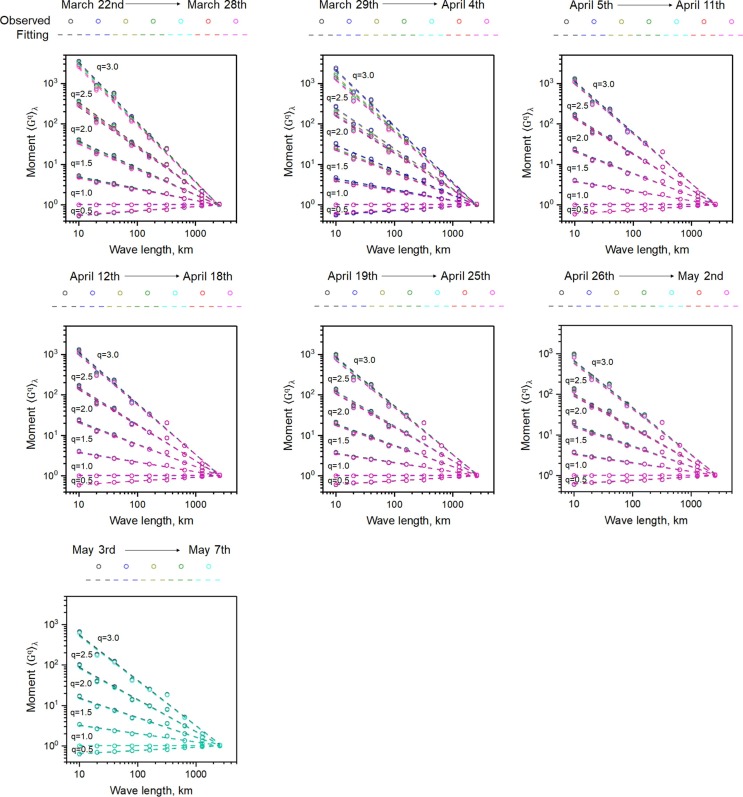

Analysis of the daily moments of county data (available March 23rd through May 7th 2020) revealed consistent scaling from 10 km to 2600 km (Fig. 3 ). Eastern US data (see divide on Fig. 1a, b) were selected for illustration because they are in closer proximity thereby allowing higher resolution to capture the 10 km scale variability. The daily moments exhibit relatively large divergence at early stage of the disease spreading (e.g., March 22nd – April 4th), and tend to converge at the later time. In particular, the orders of the moments calculated between May 3rd and May 7th almost coincide at all spatial scales, indicating that the system reached an apparent steady-state spatial correlation at that time. This is most likely due to the fact that after the travel restriction, the spatial evolution of infectious cases was mainly constrained by the spatial correlation of the population, and therefore, once the spatial patterns of the total infectious cases become close to that of the total population, the spatial correlation tends to be steady.

Fig. 3.

Moments for daily total confirmed cases in the eastern US counties. Scaling is evident from 10 km up to 2600 km at all dates that were analyzed.

The function K(q) of the UM model (Fig. 4 ) was fitted to the COVID-19 daily moment scaling exponents up to q = 1.5 due to the occurrence of phase transition [40] at q ≈ 2.0, which reflects the divergence of “dressed” moments [47]. The convex shape (upward looking) of the observed moment scaling exponents along with the fitting ones is consistently observed over the entire investigation period from later March to early May, indicating multifractal spatial correlation for the total infectious cases. Similar to the moments, the daily K(q) function evolves, and eventually reaches a steady form after May. These results deliver a strong message that the spatial correlation of the infectious cases during the contagious period can be decently characterized using multifractals.

Fig. 4.

Moment scaling function K(q) for daily total confirmed cases in the eastern US counties at various times.

Fig. 5 a and 5b depict the daily moments averaged over the duration of observation (March 20th through May 7th 2020), and temporal evolution of daily moment scaling exponents, respectively. The linear shape of moments and concave shape of moment scaling exponents consistently evidence the multifractal scaling properties from 10 km to 2600 km.

Fig. 5.

(a) The q-moments of the COVID-19 cases and their scaling from 10 km up to 2500 km used in the determination of K(q). (b) The moment scaling function K(q) is concave (upward facing) indicating multifractality.

The population variation in space was also found to be multifractal over the same scales as those of COVID-19 cases (Fig. 6 ). Power-law scaling has been reported for city sizes [32]. However, our study is first to point out multifractality. The K(q) function of the US population was obtained from Fig. 6a and is reported in Fig. 5b for comparison with those of COVID-19. The spectral slope and multifractality (α, c1, and H) are estimated to be 1.2, and (1.78, 0.15, 0.21), respectively. As the value of K(2) represents the spatial intermittency of the disease map, and one notes that this intermittency in COVID-19 cases decreased with time trending towards K(2) of the population. That is, spatial intermittency in infections exceeded the population intermittency, as expected.

Fig. 6.

(a) Moments and (b) power spectral density for the population in the eastern US counties.

The Fourier power spectrum’s slope of total COVID-19 cases (i.e., β) increased with time from 0.6 to 1.11, approaching that of the population, 1.2 (Fig. 7, Fig. 8 ). The increase was rapid until March 30th and exhibited a slow-down starting April 1st 2020. An increase in β reflects an increase in the spatial correlation, and thus it appears that COVID-19 infectious cases became spatially “distributed” based on the local population. As (Eq. (5)), its increase in time reflects both the decrease in K(2) (Fig. 5b) and the increase in H, which increased from ≈ 0.17 on March 22nd 2020 to ≈ 0.3 on May 7th 2020. The value H = 0.3 implies that only 30% of the spatial variability at a specific location is “spilled” over to neighboring locations.

Fig. 7.

Power spectral density function for daily total confirmed cases in the eastern US counties.

Fig. 8.

The fitted spectral slope of COVID-19 cases β = 1-K(2) + 2H increases with time reflecting increased spatial correlation asymptoting the spectral slope of the population. The findings here indicate that local and long-distance travel only acted as initiation ‘seeds’ of infections at the county scale, but thereafter, the natural cycle of the disease dominated the infection (mainly due to short-range human interactions within counties).

The parameter () of K(q) of total COVID-19 cases was essentially invariant in time at a value of 1.7 (Fig. 9 ) and is commensurate with that of the population, suggesting that the kernel of generation of COVID-19 is that of the population. An value smaller than 2.0 indicates that the underlying statistics are Levy-based (i.e., non-Gaussian). Also, as decreases, the likelihood of large values increases. The c1 value represents the degree of intermittency (c1 is equal to half of the variance when ). For COVID-19, c1 decreased over time from 0.42 to reach 0.3 on May 7th 2020, which is double that of the population c1 = 0.15.

Fig. 9.

Temporal evolution of (a) α and β and (b) c1 and H for total confirmed cases. The corresponding parameter values for the population are shown as dashed lines.

3.2. SIR modeling

The spectral slope of the total infected of the SIR/multifractal (Fig. 10 a) increased with time to converge to the “saturation spectrum” represented by that of the population in close agreement with the analyses of moments observations reported above. The model overshot the data in late March, possibly due to under-reporting of cases. The continuous increase in the spectral slopes of the observed new cases (Fig. 10b) in comparison with the SIR model may be reflecting the increased testing capacity in several regions in the Eastern US and the obvious deficiency in the current SIR representation, which does not allow for the number of susceptibles to change due to travel or exposure. Nevertheless, the SIR/multifractal framework showed that a reduction of R o extends the duration of a large spectral slope (i.e., a higher duration of strong spatial correlation) in agreement with observation.

Fig. 10.

Times series of observed and simulated spectral slopes of (a) total and (b) new COVID-19 cases. The simulated spectral slopes (i.e., β, Fig. 2) are based on SIR model calculations with a multifractal human population across the USA. The basic reproductive number Ro took three values prior to April 1st: 4, 4.5, and 5 then took the value of 2.0 until May 15th 2020. (a) The SIR/multifractal spectral slope agreed with the observed slope, and both converge to the population spectrum. (b) The SIR/multifractal model undershot the data possibly due to increased testing capacity across the Eastern US. Re-opening rural areas by setting Ro = 4.5 on May 15th 2020 would disturb the system through mid-July 2020, but re-opening urban centers would offset the system and the impact would be felt past September 2020.

Two hypothetical scenarios were considered within the SIR model, each to represent a top-down policy decision (e.g. at the federal level). Scenario 1 is to “re-open” all rural counties (lower 20th percentile) and Scenario 2 is to re-open all urban centers (i.e., highly populated counties), represented by the upper 20th percentile. Fig. 10b shows that both scenarios accelerate the convergence of the spatial structure of the total number of COVID-19 cases to that of the population. The SIR/Multifractal approach predicted that re-opening rural areas would be felt in the system after a few weeks (June 1st) and the impact would persist through mid-July 2020. Re-opening urban centers only (Scenario 2) would also take a few weeks to be felt in the spatial patterns of infection, but its impact would be much longer-lasting, extending throughout November 2020 (though Fig. 10b show only through September 30th for clarity). The constancy of the spectral slope of Scenario 2 during June-July indicates that the spatial correlation would maintain a dynamic equilibrium, most likely due to the abundant supply of new cases from urban centers with a large susceptible population, but then the system decays slowly over the subsequent months.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Our main finding was that COVID-19 cases obtained from US counties are multifractal, and the East of the USA (2600 km × 2000 km) exhibited consisting scaling from 10 km to 2600 km, while manifesting strong intermittency at the smaller scales (Fig. 1c, and Fig. 5). The areas of eastern counties allowed us to obtain information at the 10 km scale, but the pattern of multifractality was the same for all US counties. The ability of the UM model to simulate COVID-19 cases was illustrated in Fig. 1d, but one could also generate conditional simulations of COVID-19 cases and distribute them on county centers [30], [36]. One might be tempted to employ the travelling wave model [34] to model rapid ‘invasion’ of COVID-19 infections. However, diffusion is space-filling (i.e. it occupies the whole 2D space), and is likely to remove the intermittent behavior of COVID-19 cases over longer times.

We found that COVID-19 cases belong to a well-defined multifractality class as represented byin the Universal Multifractal model, that was essentially invariant with time, and equal to that of the human population in US (Fig. 9), which was also found to be multifractal (Fig. 6). This suggests that the kernel for the disease and the population is the same. We found that the spectral exponent of total COVID-19 cases increased with time from = 0.6 to 1.1, reflecting increases in the spatial correlation (=0 implies no spatial correlation). The increase was rapid in March 2020, slowing down subsequently with an asymptote to a population value of 1.2 (Fig. 10). Thus, the population provides a “saturation” spectrum of the total COVID-19 cases, that is, it modulates the spread the disease based on the number of susceptible people. As travel restriction was in effect since mid-March 2020, the tendency towards the population slope reflects that the seeds of the disease were already spread by that date, and that each community had COVID-19 cases and autonomously operated towards its population carrying capacity thereafter.

While the “saturation spectrum” evokes a thermodynamic limit (of spatial correlation) for the total COVID-19 cases, the kinetics of the disease are well captured using the spectrum of new cases (Fig. 10b). The SIR/multifractal framework introduced herein predicts that, under the present configuration of curfew and travel restriction, the system will be close to an equilibrium in September 2020, where the number of new cases would be sufficiently dispersed such that it would resemble uncorrelated “white noise”. This is in a qualitative agreement with the IHME prediction [15].

The approach here predicts that re-opening rural areas only would be felt in the USA after a few weeks (June 1st) and would persist through mi-July 2020 (Fig. 10b). Re-opening urban centers, on the other hand, would offset the system in a major way throughout November 2020; the ‘relaxation’ time of patterns of spatial infections will be on the order of few months, and the return to an equilibrium is predicted to be tortuous and lengthy. The analysis indicates that Federal actions require time to show effect, and they could have implications for months (100 days) rather than 2–3 weeks, as subsumed based on the recovery period of COVID-19 (14 days).

This study provided a novel way for interpreting the spatial spread of COVID-19, along with a practical approach (multifractals/SIR/spectral slope) that could be employed to capture the variability and intermittency at all scales while maintaining the spatial structure. The approach can be applied to various diseases and to various communities (e.g., countries), provided that the corresponding fundamental properties are available (or can be reasonably approximated).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

This work was funded by a RAPID grant from the US National Science Foundation (CBET 2028271). However, it does not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agency, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

Contributions

MCB, GK, and XG wrote the manuscript with contributions from EBZ and HN. FG acquired and processed the data for publication and analysis. XG developed the model and analyzed the data using multifractal techniques. Data interpretations were conducted by all the co-authors.

References

- 1.Bandoy D.D.R., Weimer B.C. Pandemic dynamics of COVID-19 using epidemic stage, instantaneous reproductive number and pathogen genome identity (GENI) score: modeling molecular epidemiology. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjørnstad O.N., Finkenstädt B.F., Grenfell B.T. Dynamics of measles epidemics: estimating scaling of transmission rates using a time series SIR model. Ecol. Monographs. 2002;72(2):169–184. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boufadel M.C., Lu S.-L., Molz F.J., Lavallee D. Multifractal scaling of the intrinsic permeability. Water Resour. Res. 2000;36:3211–3222. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brax P., Peschanski R. Levy stable law description of intermittent behaviour and quark-gluon plasma phase transitions. Phys. Lett. B. 1991;253(1–2):225–230. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinazzi M., Davis J.T., Ajelli M., Gioannini C., Litvinova M., Merler S., Piontti A.P.Y., Mu K., Rossi L., Sun K. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6489):395–400. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coburn B.J., Wagner B.G., Blower S. Modeling influenza epidemics and pandemics: insights into the future of swine flu (H1N1) BMC Med. 2009;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colizza V., Barthélemy M., Barrat A., Vespignani A. Epidemic modeling in complex realities. C.R. Biol. 2007;330(4):364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietz K., Heesterbeek J. Daniel Bernoulli’s epidemiological model revisited. Math. Biosci. 2002;180(1–2):1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(02)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedi M. Global and local multiscale analysis of magnetic susceptibility data. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2003;160:2399–2417. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frisch U., Parisi G. Fully developed turbulence and intermittency. Turbul. Predictab. Geophys. Fluid Dyn. Climate Dyn. 1985;88:71–88. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funk S., Salathé M., Jansen V.A. Modelling the influence of human behaviour on the spread of infectious diseases: a review. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2010;7(50):1247–1256. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.J. Gamero, J.A. Tamayo, J.A. Martinez-Roman, Forecast of the evolution of the contagious disease caused by novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China, arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.04739, 2020.

- 13.Gupta V.K., Waymire E. Multiscaling properties of spatial rainfall and river flow distributions. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres. 1990;95(D3):1999–2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hentschel H., Procaccia I. The infinite number of generalized dimensions of fractals and strange attractors. Physica D. 1983;8(3):435–444. [Google Scholar]

- 15.IHME . University of Washington; 2020. Institute for Health Metrics. http://healthdata.org/covid/publications. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katul G., Mrad A., Bonetti S., Manoli G., Parolari A. Global convergence of COVID-19 basic reproduction number and estimation from early-time SIR dynamics. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katul G., Vidakovic B., Albertson J. Estimating global and local scaling exponents in turbulent flows using discrete wavelet transformations. Phys. Fluids. 2001;13(1):241–250. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keeling M.J., Rohani P. Princeton University Press; 2011. Modeling Infectious Diseases in Humans and Animals. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kermack W.O., McKendrick A.G. Contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics. II.—The problem of endemicity. Proc. R. Soc. London. Series A. 1932;138(834):55–83. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kermack W.O., McKendrick A.G. Contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics. III.—Further studies of the problem of endemicity. Proc. R. Soc. London. Series A. 1933;141(843):94–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kida S. Log-stable distribution and intermittency of turbulence. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1991;60(1):5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.C. Kribs, G. Chowell, C. Castillo-Chavez, P.W. Fenimore, L. Arriola, J.M. Hyman, Model parameters and outbreak control for SARS, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kucharski A., Althaus C.L. The role of superspreading in Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) transmission. Eurosurveillance. 2015;20(25):21167. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.25.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D. Lavallée, S. Lovejoy, D. Schertzer, F. Schmitt, On the determination of universal multifractal parameters in turbulence, in: Topological aspects of the dynamics of fluids and plasmas, 1992, Springer, pp. 463–478.

- 25.D. Lavallée, D. Schertzer, S. Lovejoy, On the determination of the codimension function, in: Non-linear Variability in Geophysics, 1991, Springer, pp. 99–109.

- 26.Li R., Pei S., Chen B., Song Y., Zhang T., Yang W., Shaman J. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lovejoy S., Schertzer D. Multifractals, universality classes and satellite and radar measurements of cloud and rain fields. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres. 1990;95(D3):2021–2034. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meneveau C., Sreenivasan K. Simple multifractal cascade model for fully developed turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987;59(13):1424. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meneveau C., Sreenivasan K.R. The multifractal spectrum of the dissipation field in turbulent flows. Nucl. Phys. B-Proc. Supplem. 1987;2:49–76. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molz F.J., Boman G.K. A fractal-based stochastic interpolation scheme in subsurface hydrology. Water Resour. Res. 1993;29:3769–3774. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monin A.S., Yaglom A.M. Courier Corporation; 2013. Statistical fluid mechanics, volume II: mechanics of turbulence. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mori T., Smith T.E., Hsu W.-T. Common power laws for cities and spatial fractal structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117(12):6469–6475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913014117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papoulis A. McGraw Hill; New York: 1991. Probability, Random Variables, and Stochastic Processes; p. 666. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pastor-Satorras R., Castellano C., Van Mieghem P., Vespignani A. Epidemic processes in complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2015;87(3):925. [Google Scholar]

- 35.S. Pecknold, S. Lovejoy, D. Schertzer, C. Hooge, J. Malouin, The simulation of universal multifractals, paper presented at Cellular Automata, 1993.

- 36.Salvadori G., Schertzer D., Lovejoy S. Multifractal objective analysis: conditioning and interpolation. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk Assess. 2001;15(4):261–283. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Satsuma J., Willox R., Ramani A., Grammaticos B., Carstea A. Extending the SIR epidemic model. Physica A. 2004;336(3–4):369–375. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scardapane S., Comminiello D., Hussain A., Uncini A. Group sparse regularization for deep neural networks. Neurocomputing. 2017;241:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schertzer D., Lovejoy S. Physical modeling and analysis of rain and clouds by anisotropic scaling multiplicative processes. J. Geophys. Res. 1987;92(D8):9693–9714. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schertzer D., Lovejoy S. Hard and soft multifractal processes. Physica A. 1992;185(1–4):187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharkey P. The US has a collective action problem that’s larger than the coronavirus crisis: Data show one of the strongest predictors of social distancing behavior is attitudes toward climate change. Vox. 2020;April:10. [Google Scholar]

- 42.She Z.S., Leveque E. Universal scaling laws in fully developed turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994;72(3):336–339. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shim E., Tariq A., Choi W., Lee Y., Chowell G. Transmission potential and severity of COVID-19 in South Korea. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun F., Matthews S.A., Yang T.-C., Hu M.-H. A spatial analysis of COVID-19 period prevalence in US counties through June 28, 2020: Where geography matters? Ann. Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tennekoon L., Boufadel M.C., Lavallee D., Weaver J. Multifractal anisotropic scaling of the hydraulic conductivity. Water Resour. Res. 2003;39(7):1193. doi: 10.1029/2002WR001645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tessier Y., Lovejoy S., Schertzer D. Universal multifractals: theory and observations for rain and clouds. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1993;32(2):223–250. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veneziano D., Langousis A., Furcolo P. Multifractality and rainfall extremes: a review. Water Resour. Res. 2006;42(6) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yaglom A.M. The influence of fluctuations in energy dissipation on the shape of turbulence characteristics in the inertial interval. Soviet Physics-Doklady. 1966;11(1):26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 49.A.L. Ziff, R.M. Ziff, Fractal kinetics of COVID-19 pandemic, medRxiv, 2020.