Canada has much to be proud of with regard to the public health response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The overall mortality rate has been and continues to be significantly lower than that in the United States and lower than the UK or European Union averages (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html).

Canada announced lockdown measures in response to the pandemic on March 16, 2020, at approximately the same time as lockdowns began in several US states (March 20 in California, March 22 in New York, March 23 in Washington State). This happened despite far fewer cases per million population in Canada at the time, and this early and aggressive response has been associated with “flattening the curve.” Early in the epidemic, Canadians generally complied with the lockdown orders, although no evidence indicates that the level of community adherence early on was different between Canada and the United States.1

LESSONS FROM THE PREVIOUS SARS PANDEMIC

Much has been made of Canada’s experience with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic of 2003 as one important reason for the success of its COVID-19 response. An extremely comprehensive report was commissioned shortly after SARS,2 which led to improvements in national, provincial or territorial, and local public health infrastructure. The national chief public health officer position was created in 2004, along with the new Public Health Agency of Canada. The goal was to ensure greater federal coordination of responses to emerging infectious disease threats.

SARS primarily affected acute care hospitals, and in response to SARS, training, staffing, and routine processes in infection prevention and control in acute care hospitals were upgraded. Public health laboratories were strengthened, and this enabled testing at a critical early point in the COVID-19 pandemic to be five times higher in Canada than in the United States.3

DEATHS IN THE LONG-TERM-CARE SECTOR

In contrast to Hong Kong, SARS did not significantly affect nursing homes and long-term care (LTC) facilities in Canada. In response to SARS, Hong Kong mandated that all nursing homes have a designated infection-control practitioner and maintain at least a month’s supply of personal protective equipment (PPE).4 Canada, on the contrary, did not improve its LTC infrastructure after SARS. Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea removed patients from nursing homes and placed them in a separate quarantine center or in hospitals during COVID-19. These three regions did not have any deaths in their nursing homes during COVID-19.4

More than 840 outbreaks of COVID-19 have been reported in LTC facilities across Canada, and 81% of all deaths occurred in these settings, which in a recent study was the highest percentage among 16 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, nearly double the OECD average percentage (81% vs 42%, respectively).5 In fact, although Canada’s overall COVID-19 death rate per million population was 34% below the OECD average, its LTC death rate was 27% above the average.5 The vast majority of Canadian nursing homes did not have any infection-control practitioners, and staff did not have access to PPE and generally were not trained in its use. Compared with the OECD average, Canada had fewer health care workers (nurses and personal support workers) per 100 senior residents of LTC homes in 2018, with a rate that was half as high as the rates in the Netherlands and Norway.5 As staff became ill or were placed under quarantine from COVID-19, staffing levels collapsed.

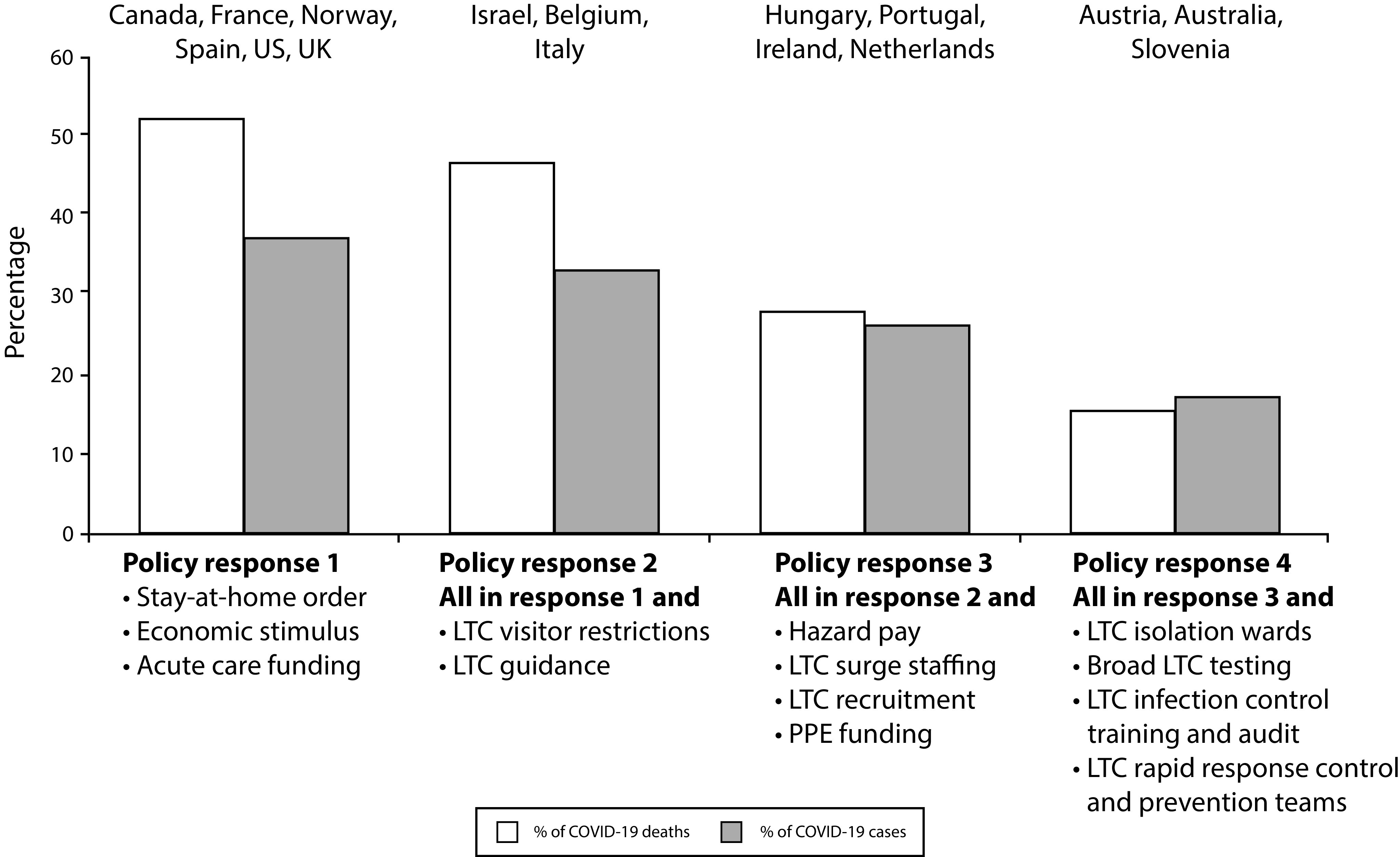

To control these nursing home outbreaks, military personnel were called on to inspect and manage many nursing homes, and, in the process, they described the extreme nature of the collapse of basic health care and infection-control practices. This emergency was particularly profound in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec. British Columbia, by contrast, promptly provided PPE to LTC staff and mandated that they do not work at multiple institutions to reduce spread. Extra funding was provided to LTC staff to compensate for loss of income resulting from not working at multiple part-time jobs. British Columbia also had more modern LTC infrastructure with fewer four-bed rooms, which helped reduce transmission. Overall, this protected British Columbia’s most vulnerable elderly, with a dramatically lower mortality than that seen in Ontario and Quebec. The policy strategies, which when implemented early were associated with lower LTC death rates, were recently re-viewed (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Effect of COVID-19 on Long-Term Care (LTC) Residents, by Level of Policy Response at the Time of 1000 COVID-19 Cases: June 2020

Note. Countries that implemented LTC prevention measures at the same time as their stay-at-home orders (Australia, Austria, the Netherlands, Hungary, Slovenia) had fewer COVID-19 infections and deaths in LTC patients. These interventions included widespread LTC testing and training, isolation wards to manage clusters, and supports for LTC workers (surge staffing, specialized teams, and personal protective equipment [PPE] supply). Countries are grouped according to which policy interventions were announced as mandatory at the time of a country’s first reported 1000 COVID-19 cases. Policy implementation can vary substantially within countries as some of these measures may be applied at the local level only. Each COVID-19 policy response includes the interventions from the previous level.

Source. Reproduced from Canadian Institute for Health Information.5 Used with permission.

PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT SUPPLY CHAIN

Canada’s supply chain for PPE was based on imports, particularly for the critical respirators (N95 masks) that were sourced primarily from the United States.6 The lack of any domestic supplier made the importance of pandemic stockpiling especially critical. The federal government maintained a national emergency strategic stockpile. However, in 2019, the federal government decided to reduce the number of warehouses and discard expired PPE, including two million respirators. These were not replaced because the federal authorities decided that maintenance of a pandemic supply of PPE would be a provincial responsibility. Ontario, Canada’s largest province and the one most affected during the SARS epidemic, initially established a pandemic PPE stockpile in the wake of SARS but unfortunately allocated funds only to maintain the warehouses but not to replace expired products. As of 2017, the expired products began to be disposed of, but the supply was not replenished. It subsequently became clear that the federal and provincial authorities were not aware that both were failing to maintain adequate reserves, with each assuming that it could rely on the other in case of an emergency. This happened despite a pandemic influenza preparedness plan that emphasized the importance of communication between the federal and the provincial or territorial governments. This plan emphasized antiviral but not PPE stockpiling.7

Unfortunately, when COVID-19 requirements for PPE rose precipitously, export controls were imposed by the countries that Canada typically used as suppliers, at which time the supply crisis rapidly escalated. Import dependence on test kits and reagents similarly impaired the ability to ramp up testing. A shortage of medical masks delayed efforts to implement universal masking of health care workers, and after exposures to patients who were subsequently found to be infected, numerous workers required home quarantine, and many became ill. This put great strain on the ability of hospitals and LTC facilities to maintain staffing. The lack of PPE necessitated aggressive conservation measures, including prolonged use of medical masks and use of expired equipment or equipment from alternative suppliers that had not previously been certified. In certain circumstances, large emergency bulk purchases from abroad had to be discarded because of failure to pass quality-control testing on arrival in Canada.

Aggressive attempts to increase domestic production eventually alleviated many of the shortfalls. However, access to respirators remains tenuous and dependent solely on imports, although plans for local factory retooling are ongoing. Currently, the N95 supply is still too limited to enable any stockpiling, and thus Canada remains at risk for a PPE shortage should a second wave appear before new suppliers come online.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, Canada learned a great deal from the SARS epidemic, with improvements in public health organization, laboratory infrastructure, and hospital infection prevention and control. Unfortunately, in areas where SARS did not affect Canada, such as the LTC sector and a collapsing supply chain, vulnerabilities remained, resulting in major challenges in the COVID-19 response.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Wright J. COVID-19: Canadians almost unanimously support the lockdown: here’s what else they think. National Post. April 8, 2020. Available at: https://nationalpost.com/opinion/canadians-almost-unanimously-support-the-covid-19-lockdown-heres-what-else-they-think. Accessed July 17, 2020.

- 2.National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health. Learning from SARS. Ottawa, Ontario: Health Canada. October 2003. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/migration/phac-aspc/publicat/sars-sras/pdf/sars-e.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2020.

- 3.Beauchamp Z. Canada succeeded on coronavirus where America failed. Why? Vox. May 4, 2020. Available at: https://www.vox.com/2020/5/4/21242750/coronavirus-covid-19-united-states-canada-trump-trudeau. Accessed July 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khazan O. The US is repeating its deadliest pandemic mistake. Atlantic. July 6, 2020. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/07/us-repeating-deadliest-pandemic-mistake-nursing-home-deaths/613855. Accessed July 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Institute for Health Information Pandemic Experience in the Long-Term Care Sector: How Does Canada Compare With Other Countries? Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; June 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poon D. A snapshot of Canada’s import structure of COVID-19 medical supplies. May 7, 2020. Available at: http://behindthenumbers.ca/2020/05/07/import-structure-of-medical-supplies. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- 7.Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness: Planning Guidance for the Health Sector. Pan-Canadian Public Health Network; August 2018. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/flu-influenza/canadian-pandemic-influenza-preparedness-planning-guidance-health-sector/table-of-contents.html#a3d2. Accessed July 22, 2020. [Google Scholar]