The United States has struggled for decades to provide its citizens appropriate and affordable medical care. To improve the efficiency and net efficacy of medical care, the first task is simply to recognize that more spending on care is not always better.

THE INVERSE U OF MEDICAL SPENDING

Physicians know that patients do best when they get the right care at the right time. Too little medical care can lead to poor outcomes, and in some cases even death. Too much medical care can also lead to poor outcomes, and in some cases also death. What is true at the individual level is equally true for the population. A society in which no resources at all are spent on medical care will have very poor health; yet a society in which all resources are spent on medical care will also have low life expectancy, as needs for food and shelter go unmet. Perched in between these extremes is the optimal amount of spending on medical care, the peak of an inverted U bridging unhealthfully low levels of medical spending to unhealthfully high levels. Excessive spending on medical care, whether through high-value care, low-value care, administrative waste, or excessive prices, is accordingly a health issue, quite independent of the quality of care delivered.

At least as far back as the 1970s, the possibility of an inverse U in medical expenditures was recognized.1 But where is the United States along this inverted U? Although the answer to this question is of course different for every health system and every patient encounter, at the macrolevel it is possible to make some informed inferences about where the average amount of spending per insured patient places us.

INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT OF US MEDICAL SPENDING

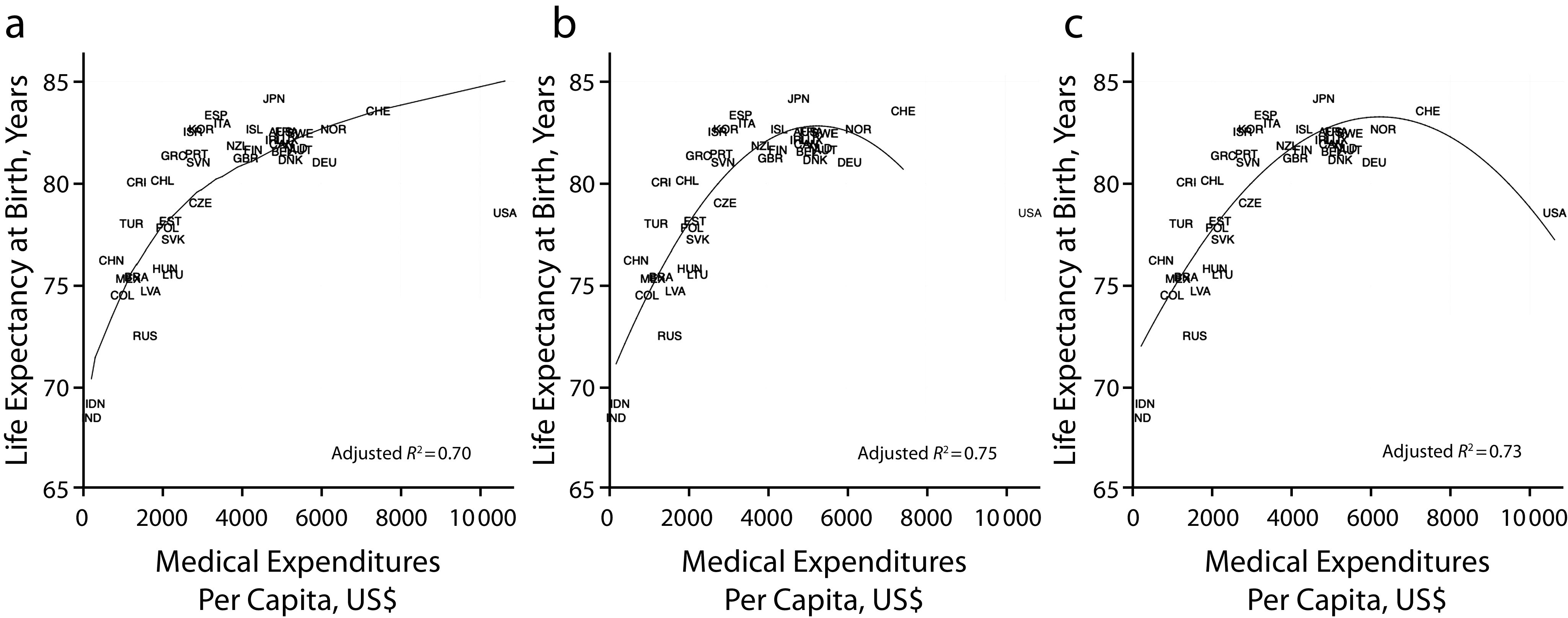

As documented by McCullough et al. in this issue of AJPH (p. 1735), high medical spending in the United States when compared with that in other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries is driven in part by high prices and by factors such as low-value care, overly intensive delivery of medical care, missed prevention opportunities, fraud, and administrative waste. Figure 1 shows three different representations of the relationship between medical spending per capita and life expectancy across wealthy countries using the most recent data from the OECD, typically 2017.2 On the left is an updated version of a graph included in a recent OECD report on health statistics.2 It shows a scatterplot of countries plotted on their coordinates of life expectancy at birth and medical expenditures per capita. Also shown is a fitted line that assumes a log–linear relationship between life expectancy and medical expenditures per capita.

FIGURE 1—

Relationship Between Medical Spending and Health Outcomes by (a) Log-Linear Form; (b) Quadratic Form, Excluding the United States; and (c) Quadratic Form, Including the United States

Note. Includes most recent data, typically from 2017.

Source. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development data.2

Graphs similar to the one on the left have appeared in news reports, on blogs, and on the Web sites of a variety of advocacy groups. All of these reproductions reinforce a strong, unsubstantiated, and highly suspect assumption: that more medical spending is necessarily associated with better health. The language that presents the United States as an outlier reinforces this assumption.

The middle panel shows the same scatterplot of data fitted to a quadratic form rather than to a log–linear form. In this graph no assumptions are made about the general direction of the relationship between medical spending and life expectancy, as this functional form is consistent with a fitted line that could be upward sloping, downward sloping, or—as evidenced here—in the form of an inverse U. Because the United States is such an extreme case, it is omitted from this panel, yet the inverse U is clear.

The graph on the right shows the same relationship and quadratic fit, this time with the United States included. In this graph, the United States is not an outlier at all but quite close to what one would expect given the amount of spending dedicated to medical care. Notably, the adjusted R2 is higher with the more flexible functional form on the right than with that on the left.

MEDICAL EXPENDITURES AND LIFE EXPECTANCY

Both the middle and right panels suggest negative marginal returns on medical spending. Why might this be? Economic theory suggests that once medical spending has surpassed its optimal level, further spending produces worse health outcomes. There are three possible reasons for this.

First, every public dollar spent on medical care is unavailable to be spent on public services that promote health outside the medical system, including education, housing, and public health. As a 2012 Institute of Medicine (now National Academy of Medicine) report noted, “Excessive allocation of national spending on medical care services poses major societal opportunity costs.”3(p4)

Second, every private dollar spent on out-of-pocket costs is a dollar unavailable to support healthy living, including to consume fruits and vegetables—often pricier than less healthful options—or more housing that offers less crowding or shorter commute times. Mental health, too, can be affected, as high premium costs have put intense stress on families already struggling with stagnant wages.

Third, overly intensive medical care, regardless of price, may produce poor health. For example, a randomized control trial of at-home monitoring for pregnant women at risk for adverse birth outcomes found that the number of unscheduled visits and use of tocolytic drugs increased among those in the treatment group, with no benefit in birth outcomes. This is wasteful spending, and the number of adverse events was higher in the treatment group, so that the effect of this reasonable-sounding intervention was in fact net negative for health.4

All of these processes suggest that there is a point beyond which societal spending on medical services can become damaging to population health. The adverse effects may be most severe among those locked out of adequate access to medical services, but they extend even to those with excellent access. The cited Institute of Medicine report argues that medical spending in the United States “goes far beyond the threshold of diminishing returns.”3(p4) The clear implication is that the marginal return on medical spending is negative: spending extra money on medical care adversely affects health, either directly or indirectly.

Of course, it could be that nonmedical attributes of the United States account for the downward-sloping portion of the curve. These attributes might cause poor health in the United States, which then drives up the demand for medical care. Such factors might include high rates of obesity in the United States, lax environmental regulation, a history of urban planning that discourages active living, structural racism, or—in recent years—high rates of opioid use.5 But if this is indeed true, it would argue for changing land use, environmental, and policing regulations or spending more money on the social determinants of health. Any of these policy changes would then permit the nation to spend less on medical care: a win–win for health and the economy.

Meeting the target for reduced expenditures will not be easy, as McCullough et al. so aptly point out, but it starts with the recognition that the United States is not an outlier. It is a country with a problem that needs to be solved, and solving it requires the avoidance of unwarranted assumptions about the functional form of the relationship of medical spending to health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The insights of the members of the Health(care) Expenditure Collaborative are gratefully acknowledged. Any errors are those of the author alone.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Lalonde M. A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians. Ottawa, Canada: Ministry of National Health and Welfare; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. For the Public’s Health: Investing in a Healthier Future. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher ES, Welch HG. Avoiding the unintended consequences of growth in medical care: how might more be worse? JAMA. 1999;281(5):446–453. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.5.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine; National Research Council. US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]