Abstract

Objectives. To demonstrate how inferences about rural–urban disparities in age-adjusted mortality are affected by the reclassification of rural and urban counties in the United States from 1970 to 2018.

Methods. We compared estimates of rural–urban mortality disparities over time, produced through a time-varying classification of rural and urban counties, with counterfactual estimates of rural–urban disparities, assuming no changes in rural–urban classification since 1970. We evaluated mortality rates by decade of reclassification to assess selectivity in reclassification.

Results. We found that reclassification amplified rural–urban mortality disparities and accounted for more than 25% of the rural disadvantage observed from 1970 to 2018. Mortality rates were lower in counties that reclassified from rural to urban than in counties that remained rural.

Conclusions. Estimates of changing rural–urban mortality differentials are significantly influenced by rural–urban reclassification. On average, counties that have remained classified as rural over time have elevated mortality. Longitudinal research on rural–urban health disparities must consider the methodological and substantive implications of reclassification.

Public Health Implications. Attention to rural–urban reclassification is necessary when evaluating or justifying policy interventions focusing on geographic health disparities.

The rural population of the United States has been historically characterized by worse health and higher mortality than the urban population.1–8 Rural–urban mortality disparities have not only persisted but in fact grown over the past 50 years.4–7 In 1970, life expectancy at birth in rural and urban areas was 70.5 and 70.9 years, respectively. By 2010, this gap had increased to 2 years, with a life expectancy of 76.8 years in rural areas and 78.8 years in urban areas.6 Likewise, although mortality decreased significantly in both rural and urban counties between 1970 and 2016, the declines were unequal; by 2016, there were 143 more rural than urban deaths per 100 000 population.7

These rural–urban disparities have been well documented, drawing renewed attention in the aftermath of the 2016 US presidential election and as concerns over so-called “deaths of despair” mount.8 However, the unstable nature of what is considered rural and urban has rarely been discussed or accounted for in this line of research. Urbanization and other population dynamics have led to significant changes in the universe of places classified as rural and urban over the past 50 years.

Each decade, the US Office of Management and Budget reclassifies counties between nonmetropolitan (henceforth “rural”) and metropolitan (“urban”) on the basis of their population size and level of economic connectivity to urban centers. Since 1970, 520 counties (16.7%) have been permanently reclassified from rural to urban according to this methodology. Likewise, we estimate that 37.2 million people living in urban counties today would have been classified as rural Americans in 1970. Urban-to-rural reclassification also occurs, but much more rarely.

Reclassification of counties is not random, and thus it complicates inferences about historical disparities between urban and rural counties. Over the past 50 years, counties reclassified from rural to urban have had, on average, higher levels of education and lower poverty rates than those that remained rural.9 In this study, we sought to demonstrate that reclassification has also complicated our understanding of rural–urban health disparities by analyzing the impact of rural–urban reclassifications on age-adjusted mortality from 1970 through 2018.

METHODS

We analyzed how county reclassification affects inferences about rural–urban disparities in total age-adjusted mortality (AAM) from 1970 to 2018 (inclusive) in the contiguous United States. All mortality data were extracted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER (Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) database.10 We produced estimates of AAM (in deaths per 100 000 population) for rural and urban counties under fixed and floating classifications and by decade of reclassification in 5-year increments between 1970 and 2015 as well as 2018.10

Although the definition has changed over time (see the Appendix, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), the Office of Management and Budget currently classifies counties as urban if they contain an urban center with a population of 50 000 or more or have strong commuting flows to an urban county.11 Counties that do not meet these requirements are classified as rural.

We assessed the implications of reclassification by producing estimates of rural and urban AAM under a counterfactual scenario in which counties’ classification (both rural and urban) was held constant at 1970. We compared estimates derived from this fixed classification of counties with estimates based on a floating classification in which counties could reclassify each decade. The floating classification has commonly been used in previous research on rural–urban disparities.6,7 To examine selection effects with respect to reclassification, we then focused on the modal rural-to-urban reclassification. We produced mortality estimates for groups of counties that were persistently rural (n = 1870), reclassified early (1980–1990; n = 190), reclassified late (2000–2010; n = 330), and were persistently urban (n = 594). (The Appendix provides a detailed explanation of AAM calculations, other methodological considerations, and mortality estimates for urban-to-rural transition counties.)

RESULTS

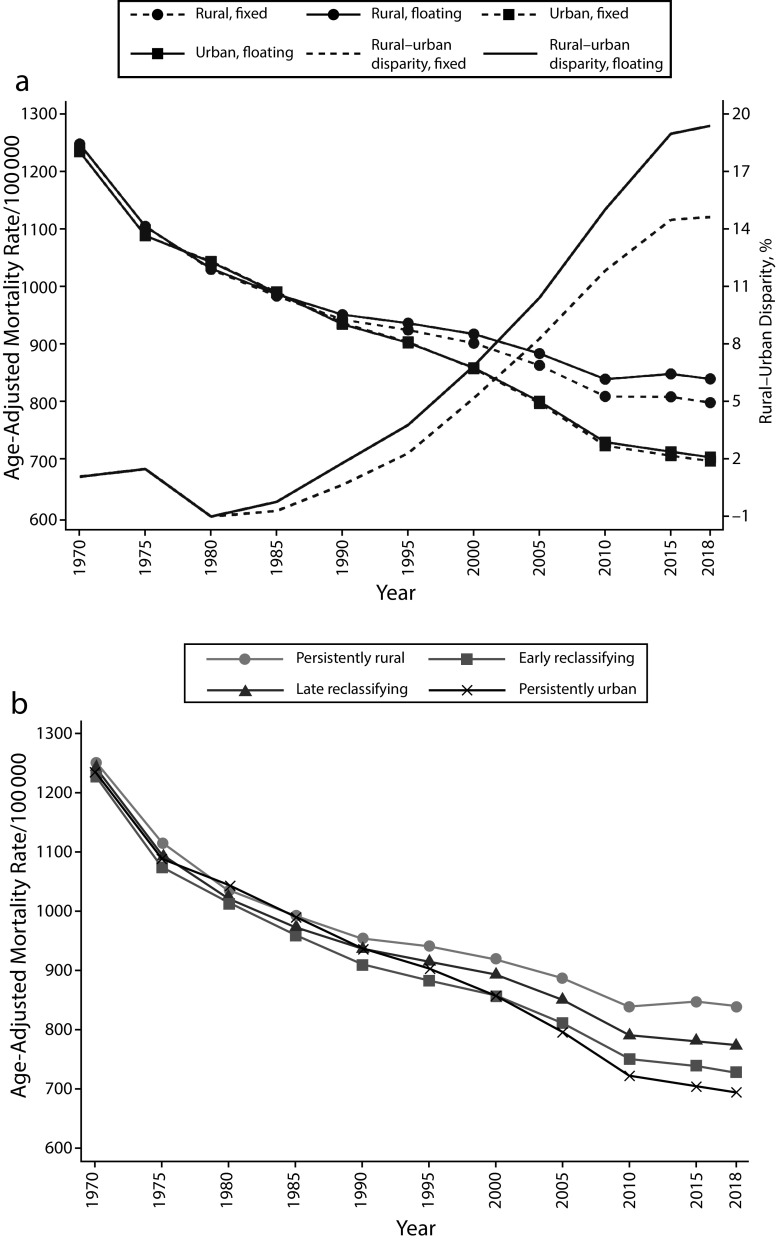

The disparity between rural and urban mortality has increased over time under both the fixed and floating classification schemes, but it is much smaller when counties’ rural–urban status is held constant at 1970 (Figure 1; see Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). In 2018, AAM was 136.4 deaths greater for the rural population than the urban population according to the floating rural–urban classification scheme. By contrast, the estimated rural–urban mortality disparity was 101.9 according to the counterfactual scenario with fixed classifications, 25.3% less than the observed value. The results also showed that both rural and urban AAM would be lower than observed, in absolute terms, if counties had never been reclassified. In such a scenario, rural mortality in 2018 would have been 41.3 deaths (4.9%) lower than under the floating scheme, and urban mortality would have been 6.8 deaths (1.0%) lower.

FIGURE 1—

Rural–Urban Disparities in Age-Adjusted Mortality by (a) Fixed and Floating Classification and (b) Decade of Reclassification: United States, 1970–2018

Our analysis also suggests that reclassification is selective on mortality, in that AAM is different on average between counties that were and were not reclassified. In 1970, AAM in both persistently rural and persistently urban counties hovered around 1240 deaths, but there was clear divergence by 2018. In 2018, AAM in counties that were rural in all decades was 144.9 deaths higher than in persistently urban counties, 111.8 higher than in early reclassifying counties, and 66.1 higher than in late reclassifying counties. These results show that, during each wave of reclassification, rural counties that were reclassified had lower aggregate AAM than those that were not. Interestingly, AAM in persistently urban counties was not lower than that in persistently rural counties until 1985 and was not lower than AAM in early or late reclassifying counties until 2000.

DISCUSSION

Changing disparities between urban and rural mortality rates since 1970 are in part a function of how counties have been reclassified over time. County reclassification since 1970 amplifies the rural mortality disadvantage observed in 2018 by 25%, which suggests that past research may have mischaracterized the growth of rural–urban health disparities. The rural mortality penalty has grown over recent decades partly because aggregate mortality rates in rural places that were reclassified to urban were lower than those in counties that remained rural. Estimates of rural–urban mortality disparities would be smaller in magnitude—although still present—if changes in rural–urban status had not occurred.

It is important to remember that reclassification reflects substantive change and is not purely a methodological artifact. For example, a rural county must have experienced population growth or integration with an urban center to be reclassified as urban. Thus, estimates of rural–urban health disparities at any single point in time are correct when the period-specific classification method is used. However, because rural–urban status is not static, caution must be exercised in any longitudinal analysis or interpretation, and researchers must assess how their chosen classification scheme may influence their findings.

Changes in rural–urban status are interwoven with changes in poverty, age structure, and health resources, and researchers must account for these disparities along with changes in rural–urban classification. Researchers who ignore urbanization may overstate the challenges facing rural America given that counties that have remained rural over time or have been reclassified may be selected on many epidemiological and demographic outcomes.9 We nonetheless have demonstrated that, regardless of whether a fixed or floating classification is used, there is a persistent rural disadvantage over time and a very real and growing disparity in mortality between urban and rural America. Public health researchers should account for the process of rural–urban transitions and integrate time-consistent classifications when possible to ensure that this growing disparity is properly described.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

Reclassification must be considered when interpreting long-term trends in urban and rural health outcomes. Rural and urban are not static categories. We found that AAM was lower in rural places that have become urban since 1970 than in those that have remained rural. If counties had not been reclassified between 1970 and 2018, rural mortality would have been lower in 2018 than observed in this study, and rural–urban disparities would be smaller.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Matthew M. Brooks and Brian C. Thiede acknowledge assistance provided by the Population Research Institute at Pennsylvania State University, which is supported by an infrastructure grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD041025). Thiede’s work was also supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture of the US Department of Agriculture (Multistate Research Project PEN04623).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no financial, institutional, or personal conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was needed for this study because no human participants were involved.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burton LM, Lichter DT, Baker RS, Eason JM. Inequality, family processes, and health in the “new” rural America. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57(8):1128–1151. doi: 10.1177/0002764213487348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James WL. All rural places are not created equal: revisiting the rural mortality penalty in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2122–2129. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959–2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996–2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer JC, Wheeler SB, Rotter JS, Holmes GM. Decomposing mortality disparities in urban and rural US counties. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):4310–4331. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder SE. Urban and rural divergence in mortality trends: a comment on Case and Deaton. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(7):E815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523659113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Widening rural-urban disparities in life expectancy, US, 1969–2009. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(2):e19–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosby AG, Maya McDoom-Echebiri M, James W, Khandekar H, Brown W, Hanna HL. Growth and persistence of place-based mortality in the United States: the rural mortality penalty. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):155–162. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erwin PC. Despair in the American heartland? A focus on rural health. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(10):1533–1534. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson KM, Lichter DT. Metropolitan reclassification and the urbanization of rural America. Demography. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s13524-020-00912-5. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER. http://wonder.cdc.gov. Accessed March 1, 2020.

- 11.Office of Management and Budget. 2010 standards for delineating metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2010/06/28/2010-15605/2010-standards-for-delineating-metropolitan-and-micropolitan-statistical-areas. Accessed September 12, 2020.