Abstract

Introduction

Management of concomitant use of ART and TB drugs is difficult because of the many drug–drug interactions (DDIs) between the medications. This systematic review provides an overview of the current state of knowledge about the pharmacokinetics (PK) of ART and TB treatment in children with HIV/TB co-infection, and identifies knowledge gaps.

Methods

We searched Embase and PubMed, and systematically searched abstract books of relevant conferences, following PRISMA guidelines. Studies not reporting PK parameters, investigating medicines that are not available any longer or not including children with HIV/TB co-infection were excluded. All studies were assessed for quality.

Results

In total, 47 studies met the inclusion criteria. No dose adjustments are necessary for efavirenz during concomitant first-line TB treatment use, but intersubject PK variability was high, especially in children <3 years of age. Super-boosted lopinavir/ritonavir (ratio 1:1) resulted in adequate lopinavir trough concentrations during rifampicin co-administration. Double-dosed raltegravir can be given with rifampicin in children >4 weeks old as well as twice-daily dolutegravir (instead of once daily) in children older than 6 years. Exposure to some TB drugs (ethambutol and rifampicin) was reduced in the setting of HIV infection, regardless of ART use. Only limited PK data of second-line TB drugs with ART in children who are HIV infected have been published.

Conclusions

Whereas integrase inhibitors seem favourable in older children, there are limited options for ART in young children (<3 years) receiving rifampicin-based TB therapy. The PK of TB drugs in HIV-infected children warrants further research.

Introduction

Currently, TB is the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent, followed by HIV.1,2 In 2018, approximately 1.7 million children <15 years old were living with HIV, of whom 100 000 died.1 Mortality amongst HIV-infected children has dramatically decreased worldwide with the introduction of combination ART.3,4 However, only half of children aged <15 years needing ART are estimated to be receiving it.5 TB is the single largest cause of death among HIV-infected patients.2 The WHO estimated that 1.1 million children developed TB in 2018 and 205 000 children died from TB disease, including 32 000 children with HIV.2 The incidence of TB has decreased6 and TB treatment outcome has improved7 amongst HIV-infected children since the introduction of paediatric ART.8 About 23% of the global population has latent TB infection (LTBI), of whom about 5%–10% eventually develop TB with increased risk in children and people living with HIV.9 Both ART and LTBI treatment reduce TB incidence in adults, but the benefit of LTBI treatment in HIV-infected children is unclear.10

Children living with HIV are eight times more likely to develop TB in moderate and high endemic areas for TB compared with HIV-uninfected children.11 Even when on successful ART, TB is an important cause of illness in HIV-infected patients.12 Both infections negatively influence progression and treatment outcome of the other infection.13 Therefore, effective treatment strategies and treatment optimization are needed to achieve control of both HIV and TB simultaneously. However, management of concomitant use of ART and TB treatment is challenging because of adherence issues, overlapping toxicities, risk of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and drug–drug interactions (DDIs).14

Dose recommendations for paediatric ART are often based on small studies, but paediatric ART dose optimization is becoming increasingly important in drug development.15 There are, however, still many knowledge gaps concerning ART in children receiving concomitant TB treatment, and vice versa.16First-line treatment of drug-susceptible TB in children consists of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol for 2 months, followed by isoniazid and rifampicin for 4 months. These medicines have been used in children for more than 40 years, initially at mg/kg doses similar to those in adults. However, exposure to (adult-dosed) TB drugs in paediatric pharmacokinetic (PK) studies was low compared with that in adults.17,18 Hence, since 2010, higher mg/kg doses are recommended for children.19 Rifabutin is also used for treatment of adult TB, but it is rarely used in children due to minimal paediatric clinical data, few paediatric formulations, limited global availability and high prices.20 Rifapentine (RPT) has recently been registered for children down to 2 years old for treatment of LTBI.10 However, it is also not used frequently in children due to availability issues and high prices.21 Paediatric dose recommendations for some drugs used for MDR-TB and HIV have only been established recently.22 Therefore, PK assessments of various MDR-TB drugs and new antiretrovirals (ARVs) have not yet been done in children with HIV-associated TB.23

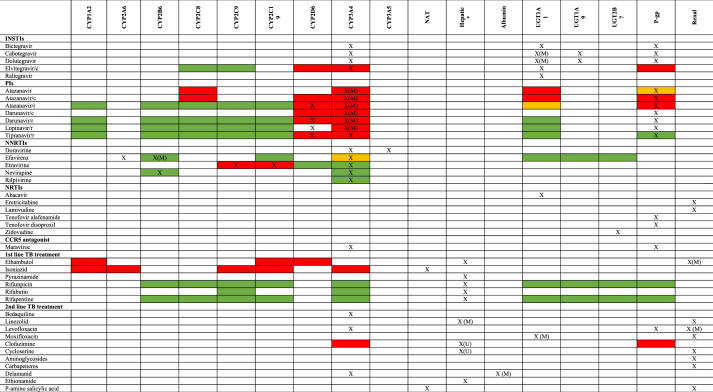

HIV and TB drug PK parameters are significant determinants of clinical response to treatment.15,24 Efficacy of most ARVs is related to trough plasma concentration (Ctrough) and to a lesser extent to AUC,15 whereas for TB treatment efficacy relates mostly to AUC and Cmax.24 PK targets for children and correlation with efficacy and toxicity are generally extrapolated from adult data.25 For TB treatment in children with HIV, low Cmax values of rifampicin and pyrazinamide are associated with TB treatment failure.26 There are many DDIs between ART and TB treatment; the most clinically significant is due to induction of many enzyme systems (see Figure 1) responsible for metabolism of ARVs by rifampicin.16 Frequently, dose adjustments are needed to overcome DDIs, or patients are switched to other ARVs when TB drugs are used concomitantly. On the other hand, PK of TB drugs can be altered in patients with HIV.27 Examples are effects of efavirenz on bedaquiline and moxifloxacin PK through enzyme induction, or lower exposure to TB drugs due to malabsorption that is believed to be caused by malnutrition, diarrhoea or infections in children with HIV.28 Dose recommendations for management of DDIs in children are often extrapolated from adults. Differences in children’s physiology, such as plasma protein binding, maturation of metabolizing enzymes and development of renal function, compared with adults can however affect drug exposure in the body and may also change the magnitude of DDIs.29 Therefore, it is of utmost importance to conduct PK interaction studies in children to evaluate proposed dosing regimens in children who are HIV/TB co-infected.

Figure 1.

Metabolic pathways and inducing/inhibitory potential of antiretroviral and TB drugs. X = metabolic pathway; X(M) = main metabolic pathway; green box = induction; red box = inhibition; yellow box = both induction and inhibition; X(U) = other hepatic metabolic pathway or unknown metabolic pathway. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

This systematic review aims to identify all literature about PK of ART and TB treatment with currently available drugs in children with HIV-associated TB, evaluate PK parameters in these studies in comparison with adult data and create an overview of the current state of knowledge. Moreover, we want to identify knowledge gaps and explore future challenges and opportunities in HIV/TB PK research in children.

Methods

This systematic review was carried out in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement to ensure systematic data collection and analysis of the literature.30

The literature search was performed in July 2019 (updated in March 2020) in both PubMed and Embase for studies about PK of ARVs or TB treatment in HIV/TB-co-infected children, with no restrictions for languages and dates. In addition, we applied the snowballing method (searching reference lists of similar studies for relevant articles) to find additional scientific papers within the scope of the review. Abstract books of relevant conferences (listed in the Supplementary data, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online) were screened for additional unpublished data related to the subject. The PubMed search included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) as well as non-MeSH key terms for TB treatment, ART, children and PK using Boolean operators. The full search strategies for both databases are included in the Supplementary data. All titles and abstracts were exported into Endnote version X9 to remove duplicates and manage references. The selection process of the relevant literature was conducted by two researchers (T.G.J. and A.C.) independently. All discrepancies were discussed until consensus on the final list of included references was reached.

Eligible studies had to report on PK parameters of TB treatment or ART in children with HIV-associated TB. Studies were excluded if no children with HIV/TB co-infection were included, no relevant PK data were reported, all results were previously published in other manuscripts without conducting new analyses or the medicines reported on are not used any longer. Due to heterogeneity of study settings, treatment, PK sampling strategy, management of DDIs and outcomes, we conducted narrative data syntheses. Information about PK parameters relating to efficacy/toxicity of the medications was extracted from the studies: AUC, Cmax, trough plasma concentration Ctrough and percentage within therapeutic range. Relative clearance and bioavailability were extracted from PK modelling studies. Quality was assessed by two researchers (T.G.J. and A.C.) using the evidence evaluation and synthesis system of DDIs described by Seden et al.31 (see Supplementary data); disagreements were resolved by consensus or referral to a third reviewer (E.S.).

Results

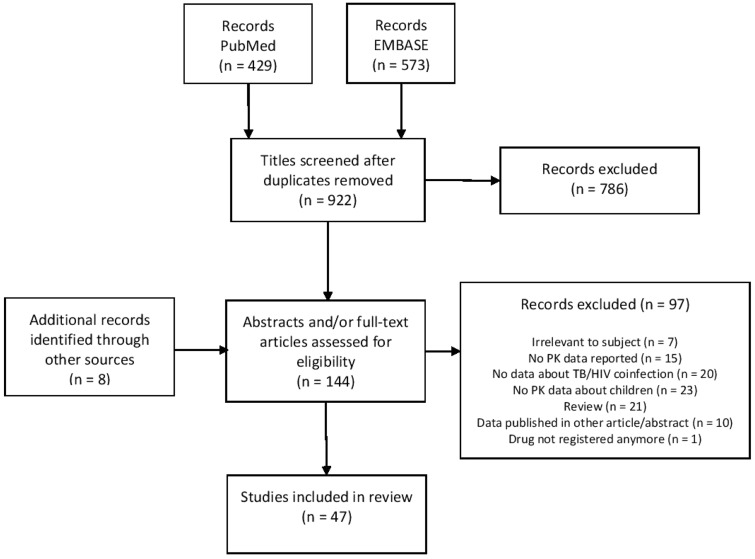

In total, 47 studies met the inclusion criteria (see the PRISMA flow chart in Figure 2): 39 were identified by literature search, 5 by the snowballing method and 3 from conference abstract books. Non-compartmental PK analysis was used in 32 studies, whereas 15 used PK modelling to estimate relevant PK parameters. Three studies assessed PK parameters of integrase strand inhibitors (INSTIs), there was one study of NRTIs, 12 of NNRTIs, 9 of PIs, 13 assessed the PK of TB treatment, 8 of MDR-TB treatment and one assesed the PK of a first-line TB drug used for LTBI treatment. All study characteristics as well as quality assessments of the studies are reported in Table 1 (DDIs) and Table 2 (PK of first-line TB drugs in children with HIV/TB co-infection). Information about the mechanism of interaction and PK data in adults is shown to compare the DDI effect size in children with that in adults.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies investigating DDIs between ARVs and TB drugs

| Reference | Study design | No. of subjects (co-infected) | Age of subjects (IQR/range/SD as reported) | PK drug; dose | PK parameters | Without perpetrator (IQR/range/SD as reported) | With perpetrator (IQR/range/SD as reported) | Effect (P value) | Conclusion | Quality of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease inhibitors | |||||||||||

| Archary, M. et al. (2018) 99 | PopPK evaluating LPV PK in malnourished children with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB on super-boosted LPV/r+ RIF-ATT | 62 [20 (10 early start, 10 late)] | Mean (SD): Early: 15.5 months (16.3) Delayed: 14.59 months (10.8) | LPV/r; WHO weight band dosage | ATT as covariate in LPV PK model | NR | NR | NS | Super-boosted LPV/r in HIV/TB-infected malnourished children resulted in similar LPV exposure compared with children without ATT | Low | |

| Elsherbiny, D. et al. (2010) 97 | PopPK evaluating LPV PK in children with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB on super-boosted LPV/r + RIF-ATT | 30 (15) + intrasubject |

|

LPV/r; WHO weight band dosage q12h or 4× higher RTV | Relative clearance (L/h) | 0.9 | 1.26 | +40% | Super-boosted LPV/r with RIF resulted in a slight increase in clearance, but with adequate predicted Ctrough values | Moderate | |

| McIlleron H. et al. (2011) 100 | NCA PK evaluating LPV PK in children with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB on double-dosed LPV/r + RIF-ATT | 44 (20) |

|

|

AUC0–8h (mg·h/L) | 49.2 (40.7–86.6) | 23.9 (13.8–49.6) | –51.4% (0.008) | Double-dosed LPV/r resulted in inadequate lopinavir concentrations in young children treated concurrently with rifampicin | High | |

| C max (mg/L) | 7.9 (6.9–13.4) | 4.5 (2.5–8.2) | –43.0% (0.008) | ||||||||

| C trough (mg/L) | 4.2 (4.3–8.1) | 0.7 (0.1–2.0) | –83.3% (<0.001) | ||||||||

| C trough <1.0 mg/L (%) | 8% | 60% | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Rabie, H. et al. (2019) 98 | PopPK evaluating LPV PK in children with HIV/TB on super-boosted LPV/r + RIF-ATT and off ATT | 96 (96) (intrasubject) | Median (IQR): 18.2 months (9.6–26.8) | LPV/r; WHO weight band dosage q12h or 4× higher RTV | C trough <1.0 mg/L (%) | 8.8% (95% CI 0.6–19.8) | 7.6% (0.4–16.2) | NS | Super-boosted LPV/r during RIF-based ATT was non-inferior to the exposure LPV/r without rifampicin | High | |

| Rabie, H. et al. (2019) 102 | NCA PK evaluating LPV PK in children with HIV/TB on 8-hourly LPV/r + RIF-ATT | 11 (11) | Median (IQR): 15 months (12.6–28.8) | LPV/r; WHO weight band dosage q12h or TDS |

|

|

|

|

These PK parameters do not support the use of an 8-hourly dosing regimen for LPV/r in children using RIF-based ATT | Low | |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Ren, Y. et al. (2008) 96 | NCA PK evaluating LPV PK in children with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB on super-boosted LPV/r + RIF-ATT | 30 (15) |

|

LPV/r; WHO weight band dosage q12h or 4× higher RTV |

|

117.8 (80.4–176.1) | 80.9 (50.9–121.7) | –31.3% (0.036) | Super-boosted LPV/r was sufficient to overcome the effect of RIF-based ATT | High | |

| C max (mg/L) | 14.2 (11.9–23.5) | 10.5 (7.1–14.3) | –26.1% (0.018) | ||||||||

| C trough (mg/L) | 4.64 (2.32–10.40) | 3.94 (2.26–7.66) | NS (0.468) | ||||||||

|

0% | 13% | – | ||||||||

| van der Laan, L. E. et al. (2018) 103 | PopPK assessing effects of INH/PZA/EMB/ETH/TRD/FQ/AMK on LPV/r PK in children with HIV/MDR-TB, including 2 children on super-boosted LPV/r and RIF | 32 (16) |

|

LPV/ 300/75 mg/m2 or LPV 300/300 mg/m2 + RIF (n=2) |

|

|

|

|

Co-administration of LPV/r with MDR-TB drugs did not significantly affect key PK parameters of LPV/r | Low | |

| Zhang, C. et al. (2012) 101 | PopPK to predict LPV/r dose to achieve target LPV exposure in children on LPV/r+RIF | 74 (24) + 11 intrasubject | Median (range): 21 months (6 months–4.5 years) |

|

|

– |

|

– | Smaller children need higher LPV/r doses when receiving RIF-ATT. 8-hourly dosing of LPV/r could be beneficial in HIV/TB-co-infected children. | Low | |

|

– |

|

– | ||||||||

|

– |

|

– | ||||||||

|

– |

|

– | ||||||||

| Zhang, C. et al. (2013) 95 | PopPK to evaluate differences in children versus adults in LPV/r exposure in patients on LPV/r + RIF-ATT |

|

Median: 21 months (6 months–4.5 years) |

|

Difference in LPV clearance (%) | NR | NR |

|

This model characterized differences between adults and children in the effect of RIF on the PK of LPV/r of lopinavir and ritonavir. | Low | |

| Difference in LPV bioavailability (%) | NR | NR |

|

||||||||

| Difference in RTV clearance (%) | NR | NR |

|

||||||||

| Difference in RTV bioavailability (%) | NR | NR |

|

||||||||

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor | |||||||||||

| Rabie, H. et al. (2020) 64 | PopPK to evaluate differences in ABC PK in children with HIV/TB on ABC versus ABC + RIF-ATT | 87 (87; (intrasubject) | Median (range): 2.8 years (0.25-6) |

|

Decrease bioavailability and AUC (%) | NR | NR | –36% | ABC exposure was decreased by concomitant administration of RIF and super-boosted LPV/r. | Moderate | |

| Integrase strand transfer inhibitor | |||||||||||

| Waalewijn, H. et al. (2020)a 40 | NCA PK evaluating DTG PK in children with HIV/TB on DTG q12h + RIF-ATT versus DTG q24h after completing ATT | 13 (13; intrasubject) | Median (range): 12.3 years (6.8–16.1) | DTG; 25 mg or 50 mg q12h on ATT and q24h off ATT |

|

|

|

|

DTG q12h was found to be safe and sufficient to overcome RIF–DTG interaction in children with HIV/TB >6 years old. | Very low | |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| C trough <EC90 25 and 50 mg (%) | 8% | 0% | – | ||||||||

| Meyers, T. et al. (2019) 45 | NCA PK evaluating RAL PK in children with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB on double-dosed RAL+RIF-ATT | 14 (14) | Median (range): 8 years (7–9) | RAL; 12 mg/kg q12h |

|

– | 17.2 (38%) | – | Doubling the dose of RAL resulted in adequate PK parameters in children (2 to 12 years old) receiving RIF-ATT | Moderate | |

| C trough (nmol/l) | – | 228 (78.4%) | – | ||||||||

| 12 (12) | Median (range): 3 years (2–5) | AUC0–12h (μmol·h/L) | – | 28.8 (50.2%) | – | ||||||

| C trough (nmol/l) | – | 229 (76.3%) | – | ||||||||

| Krogstad, P. et al. (2020) 46 | NCA PK evaluating RAL PK in infants (4 weeks–2 years) with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB on double-dosed RAL + RIF-ATT | 13 (13) | Median: 12.4 months | RAL; 12 mg/kg q12h | AUC0–12h (μmol·h/L) | – | 32.7 (49%) | – | Doubling RAL dose for TB–HIV-co-infected infants (4 weeks–2 years) receiving RIF-ATT resulted in adequate PK parameters and was safe | Moderate | |

| C trough (nmol/l) | – | 106 (57%) | – | ||||||||

| Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor | |||||||||||

| Alghamdi, W.A. et al. (2019) 82 | PopPK evaluating impact of genotype on EFV PK in children with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB on normal-dosed EFV + RIF/INH-TB | 105 (46) | Median (range): 7.1 years (3.0–14.2) | EFV; 2006 WHO-recommended dose | Relative clearance (L/h) | 7.2 | 5.7 | +26% | The model showed that RIF/INH-TB treatment did not influence EFV PK parameters | Low | |

| Bwakura Dangarembizi, M. et al. (2019) 86 | PopPK evaluating EFV PK in children with HIV/TB <3 years on RIF/INH-TB and 30% increased EFV dose | 14 (14) | Median (IQR): 14.5 months (11–23) | EFV; 2006 WHO-recommended dosefor HIV/TB 25%–33% higher |

|

– |

|

– | EFV PK variability was high. EFV dose did not need to be increased in children receiving ATT, except from extensive metabolizing children weighing >10 kg. | Very low | |

|

– |

|

|

||||||||

| Ren, Y. et al. (2009) 80 | NCA evaluating EFV PK in children with HIV/TB on normal-dosed EFV+RIF/INH-TB versus after TB treatment | 15 (15) + intrasubject | Median: HIV/TB: 6.3 years (4.3–9.0) HIV: 7.1 years (5.7–9.2) | EFV; 2006 WHO-recommended dose | C trough (mg/L) | 0.86 (0.61–3.56) | 0.83 (0.59–6.57) | – | C trough seemed to be comparable whilst on RIF/INH-TB versus after treatment discontinuation | Very low | |

| Subtherapeutic Ctrough (<1 mg/L) (%) | 60% | 53% | – | ||||||||

| Kwara, A. et al. (2019) 83 | NCA PK evaluating EFV PK in children with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB on normal-dosed EFV+RIF/INH-TB | 105 (43) + intrasubject | Median (IQR): 7.0 years (5.0–10.0) | EFV; 15.0 mg/kg (13.7–16.9) | GM (95% CI): AUC0–24h (mg·h/L) |

|

|

|

These findings support that EFV dose should not be adjusted for children receiving TB treatment | Moderate | |

| C max (mg/L) |

|

|

|

||||||||

| C trough (mg/L) |

|

|

|

||||||||

| McIlleron, H. M. et al. (2013) 84 | PopPK evaluating impact of genotype on differences in EFV PK in children with HIV/TB on RIF/INH-ATT versus after completing ATT | 81 (40) + 23 intrasubject |

|

EFV; 2006 WHO-recommended dose |

|

NR | NR |

|

Children with CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotypes had increased EFV plasma concentrations when during RIV/INH-TB treatment | Moderate | |

| von Bibra, M. et al. (2014) 81 | TDM study evaluating LPV and EFV plasma concentrations of HIV and children with HIV/TB | 29 (3) | Median: 2.2 years (0.2–7.1) | LPV; WHO weight band dosage | C trough outside therapeutic range (1.0–4.0 mg/L; %) | 17% | NR | – | RIF-ATT regimen is a potential risk factor for suboptimal EFV exposure. | Very low | |

| 24 (4) | Median: 9.3 years (3.7–15.9) | EFV; WHO weight band dosage | C trough outside therapeutic range (%) | 27% | 50% | – | |||||

| Shah, I. et al. (2011) 71 | NCA PK evaluating NVP and EFV PK in children with HIV/TB while increasing NVP dose by 20–30% or normal dosed EFV when on RIF-ATT versus after TB treatment. | 20 (5) | Mean (SD): 8.1 (3.3) years | NVP 350.9 ± 59.8 mg/m2/day + RIF; or NVP 309.2 ± 54.6 mg/m2/day |

|

81% (7% low, 15% high) | 100% | – | NVP PK was not found to be different in children using RIF when they received a 20%–30% higher NVP dose. | Very low | |

| Normal Cmax (%) | 80% (15% low, 5% high) | 100% | – | ||||||||

| 10 (2) | EFV 17.4 ± 10.2 mg/kg/day | Normal drug levels (%) | 70% (10% low, 20% high) | 100% | – | ||||||

| Enimil A. et al. (2019) 68 | NCA PK evaluating NVP PK in children with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB on normal-dosed NVP + RIF/INH-TB | 53 (23) + 16 intrasubject | Median (IQR): 1.6 years (1.1–2.0) | NVP; according to WHO guidelines | GM (95% CI) AUC0–12h (mg·h/L) |

|

|

|

Significant decrease in number of children with subtherapeutic NVP Ctrough and non-significant decrease in NVP AUC and Ctrough in HIV/TB-infected children versus HIV-infected controls. NVP PK parameters significantly decreased in TB-infected patients on versus off ATT. These data do not support NVP according to WHO weight bands. | Moderate | |

| C max (mg/L) |

|

|

|

||||||||

| C trough (mg/L) |

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Control: 30.0% | On ATT: 60.9% | (0.030) | ||||||||

| McIlleron, H. et al. (2017) 69 | PopPK evaluating NVP PK in children with HIV versus HIV/TB on normal-prophylactic dosed NVP+RIF-ATT | 164 (46b) | Range: 2–83 days | NVP; various (depending on birth weight) | Median (IQR)Ctrough (mg/L) <28 days after birth | 2.11 (1.48, 3.27) | 1.66 (1.32, 2.37) | – | NVP Ctrough was significantly reduced by RIF in newborns. Physicians should be cautious in prescribing RIF in newborns receiving prophylactic NVP | Low | |

| C trough (mg/L) ≥28 days after birth | 1.39 (1.01, 1.98) | 0.89 (0.60, 1.57) | – | ||||||||

| Overall Ctrough difference (%) | NR | NR | –33% (<0.01) | ||||||||

| Oudijk, J. M. et al. (2012) 67 | NCA PK evaluating NVP PK in children with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB on normal-dosed NVP + RIF-ATT |

|

Median (range): 1.6 years (0.7–3.2) | NVP; 18 mg/kg/day (15–23) | Median (range) AUC0–12h (mg·h/L) | 90.9 (40.4–232.1) | 52.0 (22.6–159.7) | –43% (<0.001) | Substantial reductions in NVP concentrations were found in young children receiving rifampicin | Moderate | |

| C max (mg/L) | 9.59 (5.28–21.04) | 6.33 (2.61–14.5) | –34% (<0.001) | ||||||||

| C trough (mg/L) | 5.93 (3.28–18.13) | 2.93 (1.06–11.4) | –50.6% (0.001) | ||||||||

|

0% | 52% | (0.001) | ||||||||

| Prasitsuebsai, W. et al. (2012) 72 | NCA PK evaluating NVP PK in children with HIV/TB on 12% higher dosed NVP +RIF -ATT versus after TB treatment |

|

Median (range): 9.7 years (4.4–11.7) | NVP; median (range) 149.6 mg/m2 (125.0–187.2) no RIF; and NVP 169.9 mg/m2 (148.4–252.9) with RIF | AUC0–12h (mg·h/L) | 70.8 (range: 56.1–95.5) | 85.3 (range: 40.5–170.7) | – | Children were receiving a significantly higher nevirapine dose while receiving rifampicin. The results support WHO dosing recommendations. | Very low | |

| C trough (mg/L) | 5.20 (range: 3.78–7.32) | 6.40 (range: 3.00–13.27) | – | ||||||||

|

0% | 0% | – | ||||||||

| Barlow-Mosha, L. et al. (2009)a 70 | NCA PK evaluating NVP PK in children with HIV versus peers with HIV/TB using NVP + RIF-ATT | 20 (7) | Median (range): 5.0 years (1.2–11.3) | NVP; 11 mg/kg q24h (8.0–16) | C trough (mg/L) | 4.2 (0.83–16.0) | 2.9 (1.7–10.0) | –31% (?) | Low NVP exposure was found in HIV/TB-co-infected children. | Very low | |

|

NR | 57% | NR | ||||||||

| TB treatment | |||||||||||

| Moultrie, H. et al. (2015) 119 | NCA PK evaluating RFB PK in HIV+/TB children using LPV/r | 6 (6) | Range: 10–41 months | RFB 5 mg/kg 3× week |

|

– | 6.91 (3.52–8.67) | – | Study discontinued early due to high rates of severe transient neutropenia. RFB and 25-O-desacetyl RFB exposure and Cmax were low compared with adult data | Moderate | |

|

– | 0.385 (0.19–0.46) | – | ||||||||

| Rawizza, H. E. et al. (2018)a 122 | NCA PK evaluating RFB and 25-O-desacetyl RFB PK in HIV/TB co-infected children using LPV/r | 8 (8) | Median: 13.5 (12.8–14.3) | RFB 1 DD 2.5 mg/kg | RFB AUC0–24h (μg·h/mL) | – | 4.77 | – | RFB 2.5 mg/kg daily achieved AUC0–24h comparable to adults in children receiving both LPV/r and RFB. | Low | |

| RFB Cmax (mg/L) | – | 0.4 | – | ||||||||

| 25-O AUC0–24h (μg·h/mL) | – | 2.24 | – | ||||||||

| 25-O Cmax (mg/L) | – | 0.14 | – | ||||||||

ABC, abacavir; AMK, amikacin; ATT, antituberculosis treatment; DTG, dolutegravir; EMB, ethambutol; ETH, ethionamide; EFV, efavirenz; FQ, fluoroquinolone; INH, isoniazid; LVX, levofloxacin; LZD, linezolid; LPV, lopinavir; LPV/r, lopinavir/ritonavir; MXF, moxifloxacin; NCA, non-compartmental analysis; NR, not reported; NVP, nevirapine; PK, pharmacokinetic; PK-PD, pharmacokinetics–pharmacodynamics; popPK, population pharmacokinetics; PZA, pyrazinamide; RAL, raltegravir; RIF, rifampicin; RIF-ATT, rifampicin-containing tuberculosis treatment; RIF/INH-TB, rifampicin + isoniazid-containing tuberculosis treatment; RTV, ritonavir; TDS, thrice daily; TIW, thrice weekly; TRD, terizidone.

Conference abstract.

Infants born to mothers with TB.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies investigating differences in the PK of TB drugs in children with HIV

| Reference | Study design | No. of subjects (co-infected; on ART at enrolment) | Age of subjects (IQR/range/SD as reported) | PK drug; dose(IQR/range/SD as reported) | PK parameters | TB monoinfection (IQR/range/SD as reported) | HIV/TB co-infection (IQR/range/SD as reported) | Effect (P value) | Conclusion | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line TB treatment | ||||||||||

| Antwi, S. et al. (2017) 145 | NCA PK evaluating INH/RIF/PRZ/EMB PK in children with HIV versus without HIV | 113 (59; 0) | Median (IQR): 5.0 (2.2–8.3) years | INH q24h median (IQR): 11.2 mg/kg (9.1–12.8) | Median (IQR): AUC0–8h (μg·h/mL) | 21.15 (16.48–25.92) | 18.37 (12.20–26.90) | NS (0.231) | PK parameters of RIF, PZA and EMB were adversely affected by HIV co-infection. | Moderate |

| C max (mg/L) | 5.85 (4.27–7.47) | 5.32 (4.03–7.61) | NS (0.794) | |||||||

| RIF q24h 15.8 mg/kg (13.6–18.8) | AUC0–8h (μg·h/mL) | 30.49 (21.93–38.44) | 24.88 (15.95–35.27) | –18.4% (0.030) | ||||||

| C max (mg/L) | 7.65 (5.20–9.10) | 5.83 (3.71–8.26) | –23.8% (0.025) | |||||||

| PZA q24h 24.8 mg/kg (22.6–30.0) | AUC0–8h (μg·h/mL) | 151.04 (124.64–188.81) | 126.53 (105.41 –182.34) | –16,2% (0.034) | ||||||

| C max (mg/L) | 26.90 (23.15–34.60) | 24.60 (20.60–36.50) | NS (0.259) | |||||||

| EMB q24h 16.9 mg/kg (15.0–20.6) | AUC0–8h (μg·h/mL) | 7.57 (5.16–10.68) | 4.76 (2.98–6.76) | –38.3% (<0.001) | ||||||

| C max (mg/L) | 2.28 (1.48–3.05) | 1.33 (0.75–1.92) | –41.7% (<0.001) | |||||||

| Bekker, A. et al. (2016) 144 | NCA PK evaluating INH/RIF/PRZ/EMB PK in children with HIV versus without HIV | 39 (5; 5) | Mean (SD): 6.6 months (3.0) | INH mean (range) q24h 13.8 mg/kg (9.0–19.7) | AUC0–8h | NR | NR | NS | Lower PZA and EMB exposures in HIV-infected infants were observed; however, only 5 HIV-coinfected infants were studied. | Low |

| C max | NR | NR | NS | |||||||

| RIF q24h 13.8 mg/kg (9.0–19.7) |

|

11.48 (8.66) | 16.46 (15.0) | NS (0.283) | ||||||

|

2.79 (2.00) | 3.67 (3.31) | NS (0.404) | |||||||

| PZA q24h 31.5 mg/kg (18.7–44.6) | AUC0–8h (GMR) | NR | 0.79 (0.69–0.90) | (0.001) | ||||||

| C max (GMR) | NR | 0.85 (0.75–0.96) | (0.013) | |||||||

| EMB q24h 19.9 mg/kg (13.3–29.0) | AUC0–8h (μg·h/mL) | 5.5 | 2.0 | –64% (0.008) | ||||||

| C max (mg/L) | 1.4 | 0.4 | –71% (0.004) | |||||||

| Graham, S. M. et al. (2006) 151 | NCA PK evaluating PRZ/EMB PK in children with HIV versus without HIV on thrice-weekly TB regimen | PZA 27 (18; 0) | Mean (range): 5.7 years (0.9–14) | PZA 33 mg/kg (25–48) TIW |

|

322 (240) | 411 (382) | NS | No significant differences on PZA and EMB exposure in HIV-infected children were found. Overall low PK parameters suggest need for dose increase. | Very low |

| C max (mg/L) | 41.9 (22.9) | 34.0 (18.1) | NS | |||||||

| EMB 18 (6; 0) | Mean (range): 5.5 years (1–12) | EMB 33 mg/kg (24–44) TIW | AUC0–24h (μg·h/mL) | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| C max (mg/L) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.3) | NS | |||||||

| Guiastrennec, B. et al. (2018) 150 | PK–PD analysis assessing impact of HIV infection on INH/RIF/PRZ PK and TB treatment outcome | 161 (77; 45) | 8 years (6–11) | INH 7.5–13.6 mg/kg TIW | Difference in bioavailability (%) | – | – | –19.5% | HIV/TB co-infection was related to lower INH and RIF levels rather than usage of ART. | Low |

| RIF 7.5–13.6 mg/kg TIW | Difference in clearance (%) | – | – | +31.6% | ||||||

| Difference in bioavailability | – | – | –41.5% | |||||||

| Kwara, A. et al. (2016) 146 | NCA PK evaluating INH/RIF/PRZ/EMB PK in children with HIV versus without HIV | 62 (28; NR) | Median (IQR): 5.0 years (2.8–8.9) | INH q24h 11.1 mg/kg (9.0–13.2) |

|

19.4 (13.4–25.9) | 14.3 (9.1–20.0) | NS (0.060) | High prevalence of low RIF and EMB concentrations was shown in Ghanaian children with TB despite receiving revised WHO dosages. Moreover, HIV infection was an important contributor to low exposure to most TB drugs. | Moderate |

| C max (mg/L) | 5.4 (4.2–6.4) | 4.2 (3.5–6.0) | NS (0.102) | |||||||

| RIF q24h 16.3 mg/kg (13.8–19.8) |

|

32.3 (21.1–42.3) | 20.3 (11.2–32.3) | –37.2% (0.008) | ||||||

| C max (mg/L) | 7.4 (4.9–9.3) | 5.5 (3.0–8.2) | –25.7% (0.021) | |||||||

| PZA q24h 26.6 mg/kg (23.7–32.0) |

|

165.9 (129.7–206.4) | 128.6 (94.6–194.2) | –22.5% (0.048) | ||||||

| C max (mg/L) | 30.4 (25.0–35.4) | 23.2 (19.2–36.5) | NS (0.289) | |||||||

| EMB q24h 18.4 mg/kg (15.8–22.0) |

|

8.1 (5.3–11.0) | 4.9 (3.4–7.6) | –41% (0.019) | ||||||

| C max (mg/L) | 2.4 (1.5–3.3) | 1.1 (0.7–2.4) | –54% (0.011) | |||||||

| Mukherjee, A. et al. (2016) 148 | NCA PK evaluating INH/RIF/PRZ/EMB PK in children with HIV versus without HIV | 56 (24; 19) |

|

|

|

1.31 (0.77–2.22) | 2.04 (1.53–2.74) | NS | Plasma concentrations of EMB were lower in HIV-infected children compared with HIV-uninfected children. | Low |

|

0.58 (0.35–0.97) | 0.99 (0.73–1.34) | NS | |||||||

| RIF 11.3 mg/kg (10–14.7) | AUC0–4h (μg·h/mL) | 22.62 (16.68–30.65) | 18.47 (13.29–25.67) | NS | ||||||

|

9.15 (6.69–12.51) | 7.76 (5.61–10.73) | NS | |||||||

| PZA 34.1 mg/kg (30–44.1) | AUC0–4h (μg·h/mL) | 159.0 (132.2–191.4) | 143.7 (120.5–171.3) | NS | ||||||

|

54.46 (45.12–65.71) | 55.13 (47.57–63.89) | NS | |||||||

| EMB 22.7 mg/kg (20–29.4) | AUC0–4h (μg·h/mL) | 2.79 (2.02–3.87) | 1.55 (1.06–2.25) | –44.4% (<0.05) | ||||||

|

1.13 (0.74–1.74) | 0.80 (0.53–1.19) | NS | |||||||

| Ramachandran, G. et al. (2016) 26 | NCA PK evaluating INH/RIF/PRZ/EMB PK and treatment outcome in children with HIV versus without HIV | 161 (77; 45) |

|

INH q24h 10 mg/kg |

|

22.0 (15.0–33.1) | 19.9 (10.7–30.8) | NS (0.056) | HIV-infected children had lower INH Cmax and RIF Cmax and AUC0–8h compared with uninfected children. | High |

| C max (mg/L) | 6.1 (4.0–8.4) | 4.7 (2.8–7.2) | –23% (0.008) | |||||||

|

12% | 28% | +57% (0.012) | |||||||

| RIF q24h 10 mg/kg |

|

23.4 (15.1–33.2) | 10.4 (6.1–18.2) | –55.6% (<0.001) | ||||||

| C max (mg/L) | 5.1 (3.4–6.9) | 2.6 (1.3–4.5) | –49% (<0.001) | |||||||

|

92% | 97% | NS (0.12) | |||||||

| PZA q24h 32.6 mg/kg |

|

218.2 (175.9–255.8) | 219.1 (172.6–273.9) | NS (0.452) | ||||||

| C max (mg/L) | 39.2 (30.5–44.9) | 41.2 (31.7–48.0) | NS (0.132) | |||||||

|

NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Schaaf, H. S. et al. (2009) 18 | NCA PK evaluating RIF PK in children with HIV versus without HIV | 54 (21; 0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overall plasma concentrations of RIF were low and there was a non-significant trend towards lower RIF levels in HIV-infected children. | Low |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Thee, S. et al. (2011) 147 | NCA PK evaluating INH/RIF/PRZ PK in children with HIV versus without HIV <2 years | 20 (5; 5) | Mean: 1.09 years (0.49) | INH q24h 10 mg/kg (10–15) LD 5/HD10 |

|

|

|

|

HIV-infected children had lower serum concentrations of all of the first-line TB drugs tested, but only for PZA did this difference reach statistical significance. | Very low |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| RIF q24h 15 mg/kg (10–20) LD10/HD15 |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| PZA q24h 25 mg/kg (20–30) LD25/HD35 |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Yang, H. et al. (2018) 149 | NCA PK evaluating INH/RIF/PRZ/EMB PK in children with HIV versus without HIV | 100 (50; NR) | 49.0% <5 years and 23.0% <2 years | INH median (range) 11.4 mg/kg (9.7–12.9) | C max <3 mg/L (%) | 10.0% | 8.0% | NS (1.000) | HIV co-infection status was associated with low Cmax of RIF and EMB. | Very low |

| RIF 16.5 mg/kg (14.4–19.0) | C max <8 mg/L (%) | 52.0% |

|

(0.100) | ||||||

| PZA 25.9 mg/kg (22.6–30.4) | C max <20 mg/L (%) | 10.4% | 24.5% | NS (0.108) | ||||||

| EMB 17.2 mg/kg (15.1–20.6) | C max <2 mg/L (%) | 46.9% |

|

(0.003) | ||||||

| Bekker, A. et al. (2014) 143 | NCA PK evaluating INH PK in HIV-exposed versus unexposed newborns | 20 (16; 1) | Median (IQR): 14 days ( 9–31) | INH q24h 10 mg/kg |

|

17.60 (13.27–25.08) | 13.49 (10.19–16.91) | NS (0.1306) | INH Cmax was found to be slightly lower in HIV-exposed infants. | Very low |

| C max (mg/L) | Median: 7.34 (IQR 6.14–9.39) | Median: 5.45 (IQR 4.45–6.97) | –25.7% (0.0472) | |||||||

| McIlleron, H. et al. (2009) 17 | NCA PK evaluating INH PK in children with HIV versus without HIV | 56 (22; NR) | Median (IQR): 3.22 years (1.58–5.38) | INH q24h; median (IQR) 5.01 mg/kg (4.35–9.24) | C max (mg/L) | NR | NR | NS (>0.2) | HIV infection was not associated with differences in INH Cmax. | Low |

| Second-line TB treatment | ||||||||||

| Denti, P. et al. (2018) 158 | PopPK evaluating LVX PK in children with HIV versus without HIV having MDR-TB | 109 (16; 13 LPV/r, 3 EFV) | Median (range): 2.1 years (0.3–8.7) | LVX q24h 15 or 20 mg/kg |

|

4.70 (4.37, 5.00) | NR | –15.9% (–26.6 to –5.93) | HIV infection was associated with a lower LVX clearance, although unlikely to be clinically significant. | Very low |

| Garcia-Prats, A. J. et al. (2015) 154 | NCA PK evaluating OFX PK in children with HIV versus without HIV having MDR-TB | 85 (11; NR) | Median (IQR): 3.4 years (1.9–5.2) | OFX q24h 20 mg/kg |

|

44.4 (10.6) | 42.5 (9.0) | NS (0.560) | No effect of HIV infection on OFX PK was observed. | Low |

|

9.05 (2.44) | 8.42 (1.51) | NS (0.404) | |||||||

| Garcia-Prats, A. J. et al. (2019) 159 | PopPK evaluating LZD PK in children with HIV versus without HIV having MDR-TB | 48 (3; NR) | Median (range): 4.6 (0.6–15.3) years | LZD q12h 10 mg/kg (<10 year) LZD q24h 10 mg/kg (>10 year) | Difference in clearance (%) | – | – | NS | Study was underpowered to show a clinically relevant effect of HIV on LZD PK. | Very low |

| Bjugard Nyberg, H. et al. (2018) 162 | PopPK evaluating ETH PK in children with HIV versus without HIV having MDR-TB | 119 (24; 14 LPV/r, 6 EFV) | Median (range): 2.6 years (0.25–15) | ETH q24h 20 mg/kg | Difference in bioavailability (%) | – | – | –22% (<0.001) | ETH bioavailability was reduced in HIV-infected children. | Very low |

| Liwa, A.C. et al. (2013) 160 | NCA PK evaluating PAS PK in children with HIV versus without HIV having MDR-TB | 10 (4; 4 EFV) | Median: 4 years (1–12) | PAS q12h 75 mg/kg or PAS q24h 150 mg/kg | AUC0–2h (μg·h/mL) | NR | NR | NR | The mean concentrations (not reported) at all timepoints were lower in HIV-infected patients, without significant differences. | Very low |

| C max (mg/L) | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Thee, S. et al. (2014) 153 | NCA PK evaluating OFX and LVX PK children with HIV versus without HIV having MDR-TB | 22 (4; NR) | Median (IQR): 3.14 years (1.3–4.0) | LVX q24h 15 mg/kg |

|

31.38 (24.41–36.39 | 27.49 (24.73–34.03) | NS (0.67) | No significant differences in LVX and OFX were seen due to HIV infection in children, possibly because of the small sample size. | Very low |

| C max (mg/L) | 6.88 (5.36–8.06) | 4.98 (4.52–7.48) | NS (0.39) | |||||||

| OFX q24h 20 mg/kg |

|

44.67 (36.73–54.46) | 39.01 (33.47–48.06) | NS (0.55) | ||||||

|

9.86 (8.09–11.57) | 7.69 (6.21–9.39) | NS (0.25) | |||||||

| Thee, S. et al. (2015) 152 | NCA PK evaluating MXF PK in children with HIV versus without HIV having MDR-TB | 23 (6; 2 LPV/r, 4 EFV) | Median (IQR): 11.1 (9.2–12.0) | MXF q24h 10 mg/kg |

|

19.98 (16.71–25.21) | 13.19 (11.89–15.90) | −34% (0.003) | HIV-infected children were found to have lower MXF exposure compared with HIV-uninfected children. | Very low |

|

3.21 (2.95–3.82) | 2.83 (2.36–2.94) | NS (0.080) | |||||||

| Thee, S. et al. (2011) 161 | NCA PK evaluating ETH PK in children with HIV versus without HIV having MDR-TB | 31 (7; 7) | Range: 3 months–13 years | ETH q24h 15–20 mg/kg |

|

NR |

|

|

ETH exposure was found to be lower in HIV-infected children compared with uninfected children. | Very low |

|

NR |

|

|

|||||||

AMK, amikacin; ATT, antituberculosis treatment; q12h, twice daily; EMB, ethambutol; ETH, ethionamide EFV, efavirenz; FQ, fluoroquinolone; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; INH, isoniazid; LVX, levofloxacin; LZD, linezolid; LPV, lopinavir; LPV/r, lopinavir/ritonavir; MXF, moxifloxacin; NCA, non-compartmental analysis; NR, not reported; OFX, ofloxacin; PAS, para-aminosalicylic acid; PK, pharmacokinetic; PK-PD, pharmacokinetics–pharmacodynamics; popPK, population pharmacokinetics; PZA, pyrazinamide; q24h, once daily; RIF, rifampicin; RIF-ATT, rifampicin-containing tuberculosis treatment; RTV, ritonavir; TIW, thrice weekly; TRD, terizidone.

Effects of TB drugs on ART

Drugs used for TB treatment affect PK parameters of many ARVs. Rifampicin is a strong inducer of cytochrome P450 (CYP)2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) and P-glycoprotein (P-gp).32 The induction potential of rifapentine is slightly less than or comparable to that of rifampicin. Very few studies have directly assessed differences in DDI magnitude between ART and rifapentine or rifampicin.33,34 Rifabutin is known to be a less potent CYP inducer compared with rifampicin and rifapentine.35 Isoniazid is known to inhibit CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2E1 and CYP3A4 to some extent,36 but the inhibiting effect of isoniazid is outweighed by the strong inducing effect of rifampicin when both are used in combination. Rifampicin and rifabutin are mainly used for treatment of TB, whereas rifapentine is predominantly used for LTBI treatment, and isoniazid is used for both treatments. The effects of TB treatment (perpetrator drugs) on ARVs (victim drugs) in children are described below.

Integrase strand transfer inhibitors

A dolutegravir-based ART regimen has recently been included in the WHO guidelines as the preferred first-line regimen in children weighing >20 kg.37 Dolutegravir is primarily metabolized by UGT1A1 and to some extent by CYP3A, while rifampicin strongly induces those enzymes,32 leading to lower dolutegravir exposure in adults (AUC0–tau −54%; Ctrough −72%).38 It has been shown in adults receiving rifampicin that increasing dolutegravir dose to 50 mg twice daily (q12h) is safe and results in a similar exposure compared with dolutegravir 50 mg once daily (q24h) without rifampicin (AUC0–24h +33%; Ctrough +22%).38,39Co-administration of dolutegravir q12h and rifampicin has been investigated in 13 children 6–18 years old with HIV and TB, receiving either 25 mg or 50 mg dolutegravir q12h. An intrasubject comparison of dolutegravir PK parameters on TB treatment (q12h dolutegravir dosing) with dolutegravir PK parameters after stopping TB treatment (with rifampicin) showed that the AUC0–24h was similar for both situations. Moreover, while on dolutegravir q12h with rifampicin, all children had therapeutic Ctrough, and no safety issues in this study were related to dolutegravir.40Twice-daily dolutegravir dosing in children >6 years old, following the 2019 WHO dose recommendation for children, is assumed to be safe and sufficient to attenuate the interaction with rifampicin. More research is needed to strengthen these results and evaluate the strategy in younger children and when the adult dose of 50 mg dolutegravir is given to children of 20–25 kg.

Raltegravir is predominantly metabolized by UGT1A1. PK data of raltegravir seem different in HIV/TB-co-infected adults compared with healthy adults. One study with healthy volunteers reported a 61% decrease in Ctrough due to rifampicin, and Ctrough remained 53% lower when double the dose of raltegravir (800 mg q12h) was given with rifampicin, compared with raltegravir (400 mg q12h) only.41 In contrast, a study in patients with HIV/TB co-infection suggested that doubling the dose of raltegravir overcompensates for rifampicin induction (Ctrough +68%), whereas the standard raltegravir dose with rifampicin resulted in only a 31% decrease in trough concentration of raltegravir.42,43 However, non-inferiority after 48 weeks of treatment could not be statistically demonstrated for raltegravir 400 mg q12h compared with efavirenz 600 mg q24h in adults with HIV-associated TB using rifampicin-based TB treatment simultaneously, and thus is not recommended as first-line therapy.44 PK parameters of adjusted doses of raltegravir have been studied in children 2–12 years old receiving 12 mg/kg q12h during concomitant rifampicin, instead of 6 mg/kg q12h.45 Geometric means of raltegravir AUC0–12h and Ctrough were within the predefined target range.45 In addition, raltegravir data in infants (4 weeks to 2 years old) have been published recently; doubling the dose of raltegravir chewable tablets (12 mg/kg; crushed and dispersed in water) while taking rifampicin achieved adequate PK levels and was found to be safe.46 Given the observed PK data in children with HIV/TB receiving double-dose raltegravir, this approach seems to be suitable for children receiving rifampicin concomitantly.

The use of bictegravir is not recommended in combination with rifampicin. Bictegravir exposure in healthy adults without HIV or TB was found to be 80% lower when dosed once daily with rifampicin, and doubling the dose by giving it twice daily did not mitigate the drug interaction, as exposures were still reduced by 60% in contrast to raltegravir and dolutegravir. This might be due to differences in metabolism; CYP3A4 and UGT1A1 equally contribute to bictegravir metabolism, whereas dolutegravir and raltegravir are mainly metabolized by UGT1A1.47 The clinical consequences of the bictegravir–rifampicin drug interaction have not been explored in patients. There have been no DDI studies in children receiving bictegravir together with TB drugs. Elvitegravir needs boosting by cobicistat to achieve therapeutic plasma concentrations and its metabolism is similar to that of bictegravir. There is no paediatric formulation of elvitegravir/cobicistat, hence it is only available for older children. Co-administration of elvitegravir/cobicistat and rifampicin has not yet been studied, but it is contraindicated because large decreases in elvitegravir/cobicistat exposure are expected.48

There is no clinically meaningful effect of rifabutin on raltegravir and dolutegravir exposure in adults,38,49 but this has not yet been investigated in children. In adult patients with HIV, use of dolutegravir q24h together with rifapentine once weekly appeared to be well tolerated and led to a reduction of dolutegravir exposure that was probably not clinically significant.50 Raltegravir exposure was also found to be sufficient in healthy adults receiving concomitant rifapentine.51

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

Limited studies have been reported that assess NRTI PK in combination with rifampicin-based TB treatment in adults. Both abacavir and zidovudine are metabolized by UGT, and rifampicin is known to induce UGT.52 Two studies reported decreases of zidovudine exposure (close to −50%) due to concomitant use of rifampicin in HIV-infected adults,53,54 whereas no studies reported on abacavir PK in adults with TB treatment. Only one study reported on PK of NRTIs in children using rifampicin; the authors found an average decrease in abacavir exposure of 36% due to rifampicin-based TB treatment in children <6 years old also receiving super-boosted lopinavir/ritonavir.55 It is uncertain whether or not this is clinically relevant, since its antiviral effect is due to the intracellular anabolite, carbovir triphosphate, which was not measured56 and NRTI plasma concentrations do not necessarily correlate with antiviral activity of the drug.57 Also, ART always consists of multiple ARVs that might compensate for loss in efficacy of the other ARV. Of all children, 82% were virologically suppressed by the end of the study when receiving rifampicin-based TB treatment, which is in line with children without TB treatment.55

Tenofovir alafenamide is a substrate of drug transporters such as P-gp and breast cancer resistance protein.58 Rifampicin affects tenofovir alafenamide metabolism by inducing expression of these drug transporters.59 Plasma concentrations of tenofovir and tenofovir alafenamide and intracellular tenofovir diphosphate were reduced by concomitant use of rifampicin in adults. However, intracellular tenofovir diphosphate concentrations were still 4-fold higher compared with patients using tenofovir disoproxil, indicating that this might not be clinically relevant.60 No research has been done in children yet. Tenofovir disoproxil absorption is less P-gp dependent compared with tenofovir alafenamide. Therefore, tenofovir concentrations after tenofovir disoproxil treatment do not significantly change due to concomitant rifampicin either in healthy volunteers or in adults who are HIV/TB co-infected.61,62Co-administered ritonavir-boosted ARVs can also potentially modify this interaction by ritonavir-related induction of P-gp and UGT.63Super-boosted ritonavir seemed to contribute minimally to reducing abacavir exposure compared with rifampicin,64 but tenofovir alafenamide and tenofovir disoproxil PK has not yet been studied with co-administration of both rifampicin and ritonavir. Emtricitabine plasma concentrations and intracellular emtricitabine triphosphate concentrations were also found to be unaffected by rifampicin-based TB treatment in adults.60 Lamivudine PK has not been investigated at all in patients receiving rifampicin. Paediatric studies are needed to confirm the results of adult studies of NRTI PK and rifampicin, especially for tenofovir alafenamide and tenofovir disoproxil.

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

Metabolism of nevirapine is primarily through CYP3A4 and to a lesser extent CYP2B6. and therefore it is affected by rifampicin.65 Decreases of AUC0–12h (−58%) and Ctrough (−68%) have been reported in adults.66 In total, six studies reported on nevirapine PK parameters when co-administered with rifampicin in children. Two studies reported decreased nevirapine exposure (about 40%) due to rifampicin-based TB treatment given at 10 mg/kg67 and 15 mg/kg68 in children under 3 years old. Moreover, significantly more children on rifampicin compared with peers without rifampicin had nevirapine trough levels <3.0 mg/L (51% versus 0%67 and 61% versus 30%68), which is considered subtherapeutic. Both in newborns using rifampicin for TB prevention (10 mg/kg) and in children between 1 and 11 years old using rifampicin-based TB treatment, nevirapine trough concentrations were found to be reduced by about 30%.69,70 Shah et al.71 found that increasing the nevirapine dose by 20%–30% in older children [mean (SD): 8.1 (3.3) years] receiving rifampicin-based TB treatment resulted in a similar exposure compared with children receiving nevirapine without rifampicin. Another study from Thailand, including eight children >3 years old with HIV-associated TB, found no children with inadequate nevirapine Ctrough during rifampicin co-administration.72 This might be due to genetic differences in Thai children or the low number of children included in the study. Overall, most studies report reduction of nevirapine exposure in children receiving rifampicin-based TB treatment. The WHO recommends the use of nevirapine at the maximum weight/age-appropriate dose (200 mg/m2) only in children with HIV/TB under 3 years old, but not for older children because of other available options with more robust ARVs.73

Efavirenz is metabolized to an inactive metabolite mainly by CYP2B6 and to a lesser extent by CYP2A6 and UGT2B7.74 The prevalence of CYP2B6 polymorphisms is high in TB- and HIV-endemic areas such as Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (range: 10%–28% slow metabolizers and 34%–50% extensive metabolizers), resulting in wide efavirenz PK variability.75 Rifampicin is known to induce CYP2B6,32 leading to a decrease of efavirenz AUC by 26% when used with efavirenz in healthy adults.76 In contrast, isoniazid might contribute to an increase in efavirenz exposure by inhibiting CYP2A6 activity.77 No clinically significant alterations in efavirenz PK were found in adults with HIV-associated TB using efavirenz 600 mg q24h and rifampicin/isoniazid-based TB treatment; genetic CYP2B6 polymorphisms had a larger impact on efavirenz exposure.75 Recent PK data suggest that efavirenz 400 mg q24h can also be considered in adults and adolescents.78 The efavirenz PK profile is favourable when administered with rifapentine and isoniazid in adults, but has not been investigated in children.79 The potential interaction between efavirenz- and rifampicin-based TB treatment in children was investigated in seven studies. No substantial differences in efavirenz PK were seen in children >3 years old using low-dose first-line TB treatment.71,80–82 More recently, a PK study including 144 children between 3 and 14 years old confirmed these findings with higher isoniazid (10 mg/kg) and rifampicin (15 mg/kg) dosages being given.83 Efavirenz PK parameters were slightly higher in patients on rifampicin/isoniazid-based TB treatment, but these findings were not considered to be clinically relevant.83

McIlleron et al.84 showed that average efavirenz mid-dose interval concentrations increased by 1.49-fold in children with CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotypes when receiving concomitant rifampicin/isoniazid-based TB treatment compared with efavirenz without TB drugs. No differences were found in children with genotypes for intermediate and fast CYP2B6 metabolism.84 This finding is explained by the assumption that the inhibitory effect of isoniazid on CYP2A6 becomes more relevant in slow CYP2B6 metabolizers.85 Another study assessed efavirenz PK in HIV/TB-co-infected children <3 years old with a genotype-based dosing approach.86 Poor metabolizers were given 25% of the efavirenz dose, and the efavirenz dose was increased by ∼30% for all children who received rifampicin-based TB treatment, regardless of CYP2B6 genotype. Increasing the dose was not necessary, since 46% of all included children had supratherapeutic Ctrough (>4.0 mg/L). PK variability was high in this study despite genotype-based dosing.86 Due to highly variable efavirenz PK, efavirenz is not generally recommended in children aged <3 years.73 Although efavirenz exposure is largely dependent on CYP2B6 and CYP2A6 genotype, genotype testing is expensive and genotype-based efavirenz dosing is not practical, and therefore it is not recommended.73 No efavirenz dose adjustments are necessary for children and adults during rifampicin-based TB treatment.

Use of doravirine, etravirine or rilpivirine together with rifampicin-based TB treatment is contraindicated. All these NNRTIs are mainly metabolized through CYP3A4.87 Enzyme induction by rifampicin leads to large decreases in doravirine, etravirine and rilpivirine exposure in adults: AUC0–tau −88%,88 AUC0–12h about −55%,89 and AUC0–24h −80%, respectively.90 No studies have been done in children.

Protease inhibitors

PK parameters are an important indicator for lopinavir efficacy; Moholisa et al.91 found that virological failure correlates with lopinavir trough concentrations below 1.0 mg/L. Lopinavir is co-administered with ritonavir, a potent inhibitor of CYP3A, in a 4:1 ratio to achieve higher (effective) lopinavir exposure. Rifampicin is a strong inducer of CYP3A,32 leading to large decreases in plasma concentrations of lopinavir (AUC −75%) in healthy adults.92 The interaction can be overcome by doubling the lopinavir/ritonavir dose92,93 but, due to an increased risk of hepatotoxicity, this is not recommended.94 Replacement of rifampicin by rifabutin (150 mg q24h due to bidirectional DDI) is preferred for first-line TB treatment in adults, because rifabutin has little effect on lopinavir/ritonavir exposure.76 Lopinavir/ritonavir currently is the preferred anchor drug in ART for children younger than 3 years old.73 Bioavailability of lopinavir is reduced by 25% in adults due to co-administration of rifampicin-based TB treatment, whereas bioavailability decreases by 59% in children.95 To compensate for this DDI, three strategies have been studied in children; double-dose lopinavir/ritonavir (ratio 8:2), 8 hourly lopinavir/ritonavir dosing (ratio 4:1) and super-boosting by increasing the ritonavir dose to 1:1 ratio with lopinavir.

A PK proof-of-concept study found that the lopinavir/ritonavir super-boosting strategy (ratio 1:1) was effective in attenuating enzyme induction by rifampicin in children.96 Although lopinavir AUC was 31% lower96 and clearance 30% higher97 in children while on rifampicin-based TB treatment compared with off TB treatment, lopinavir Ctrough was similar and 13/15 patients had therapeutic trough levels (>1.0 mg/L). The efficacy of this strategy was later confirmed in a larger modelling study in children of 3–15 kg (including infants <1 year) by showing non-inferiority of lopinavir Ctrough during rifampicin co-treatment.98 The researchers predicted that 92% of all patients receiving super-boosted lopinavir/ritonavir with rifampicin would reach trough concentrations above 1.0 mg/L. Overall, super-boosted lopinavir/ritonavir was well tolerated, even though caregivers reported difficulties administering extra ritonavir because of low acceptability of the drug formulation.98Super-boosted lopinavir/ritonavir also resulted in similar lopinavir exposure in malnourished children with HIV/TB co-infection compared with children without TB treatment.99

Double-dosed lopinavir/ritonavir (ratio 8:2) in children younger than 3 years old (n = 17; median age 1.25 years) receiving rifampicin-based TB treatment resulted in inadequate lopinavir trough concentrations compared with children receiving lopinavir/ritonavir without TB treatment.100 Only 40% of children receiving lopinavir/ritonavir double dose had Ctrough greater than 1.0 mg/L, whereas 92% of the control group achieved therapeutic trough concentrations. The differences between children and adults were explained by a lower bioavailability of lopinavir due to low ritonavir concentrations.95Double-dosed lopinavir/ritonavir given with rifampicin has not been studied in children >3 years old.

Based on simulations from a population PK model, it was expected that at least 95% of children would have lopinavir trough concentrations of at least 1.0 mg/L when using lopinavir/ritonavir thrice daily in combination with rifampicin-containing TB treatment.101 However, a study in children with HIV-associated TB reported that 36% of 11 children did not achieve lopinavir Ctrough >1.0 mg/L when using this treatment strategy.102

The effect of MDR-TB drugs on lopinavir/ritonavir PK was assessed in one small study which included 16 children receiving combinations of high-dose isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, ethionamide, terizidone, a fluoroquinolone and amikacin, and 16 controls without MDR-TB.103 No significant differences were found between the two groups; 81% of children with MDR-TB versus 88% of controls had therapeutic Ctrough.103

Atazanavir, darunavir and saquinavir are contraindicated in adults when co-administered with rifampicin due to safety and efficacy concerns. Ritonavir-boosted atazanavir co-administered with rifampicin resulted in very large decreases in exposure of atazanavir (AUC0–tau −72%; Ctrough −98%).104 For darunavir, doubling the dose when used twice daily resulted in similar Ctrough compared with normal doses without rifampicin in adults with HIV.105 However, this study was discontinued early due to severe hepatotoxicity, as were studies with co-administration of rifampicin and ritonavir-boosted atazanavir or saquinavir.105–107 No studies have been conducted with boosted PIs other than lopinavir/ritonavir in HIV/TB-co-infected children. The effect of rifampicin-based TB treatment on cobicistat-boosted PIs has not been determined yet. Concomitant use of rifabutin slightly increased darunavir exposure and had very little effect on atazanavir PK in healthy volunteers.108,109Co-administration of rifapentine and PIs has not been studied, but is expected to result in large decreases of PI plasma concentrations.

Effects of ART on TB drugs

First-line TB drugs

Metabolism of rifampicin and rifapentine is through esterases in liver microsomes and to some extent by renal excretion.110 The major metabolism pathways of isoniazid are by acetylation through N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2) and hydrolysis through amidase.111 Pyrazinamide is converted into pyrazinoic acid by microsomal deamidase and further metabolized by xanthine oxidase enzymes.112 Approximately 80% of ethambutol is excreted renally and 20% is metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase.113 None of these metabolic pathways is expected to be affected by ARVs.

Rifabutin is both an inducer and a substrate of CYP3A, so DDIs with ARVs are potentially bidirectional. It is predominantly metabolized into its equally active metabolite 25-O-desacetylrifabutin by CYP3A4.114 This metabolite accounts for up to 10% of the total antimicrobial activity of rifabutin in adults without interacting medication.115 Efavirenz is known to decrease rifabutin plasma concentrations through induction of CYP3A4,116 but this interaction has not been studied in children.

Lopinavir/ritonavir is known to interact with rifabutin through inhibition of CYP3A enzymes by ritonavir, leading to high exposure of rifabutin and its active metabolite, and an increased risk of dose-dependent toxicities such as uveitis and bone marrow depression.76 Recently, the dose recommendation of rifabutin was increased from 150 mg thrice weekly to 150 mg q24h when co-administered with lopinavir/ritonavir instead of 300 mg q24h without interacting medications.117,118 This DDI was studied in children under 5 years old that were already cured of TB receiving 5 mg/kg rifabutin thrice weekly instead of the recommended 10–20 mg/kg q24h without lopinavir/ritonavir. The study was discontinued because the neutrophil count declined in all six children receiving both rifabutin and lopinavir/ritonavir; two of them experienced grade 4 neutropenia.119 Surprisingly, rifabutin Cmax was below the target range for therapeutic drug monitoring (0.45–0.9 mg/L) in four out of six children.119 The median rifabutin and 25-O-desacetylrifabutin exposures were higher compared with most studies in adults using thrice-weekly 150 mg rifabutin co-administered with lopinavir/ritonavir, but lower compared with adults receiving 150 mg rifabutin q24h with lopinavir/ritonavir. Rawizza et al.120 rarely found neutropenia in 48 young children with HIV-associated TB [median (IQR) age: 1.7 years (0.9–5.0)] receiving a 6 month course of 2.5 mg/kg/day rifabutin and lopinavir/ritonavir, although the absolute neutrophil count declined slightly. The rifabutin course was completed with no TB symptoms in 79% of participants after 12 months of follow-up. The different safety findings were suggested to be caused by differences in patient characteristics, i.e. children who were HIV infected versus HIV/TB co-infected. Rifabutin-associated neutropenia has also been observed more frequently in healthy adults compared with adults with HIV-associated TB.121 Rawizza et al.122 also presented an interim analysis of eight older children [median (IQR) age: 13.5 years (12.8–14.3)] receiving 2.5 mg/kg/day rifabutin with lopinavir/ritonavir. Rifabutin and 25-O-desacetylrifabutin exposure in these children was slightly lower compared with the findings of Moultrie et al.119 (see Table 1), whereas Cmax of both substances was comparable.122 Exposure of 25-O-desacetyl rifabutin was 4-fold higher compared with adults receiving rifabutin 300 mg q24h without lopinavir/ritonavir, which is consistent with data from Moultrie et al.119 and adults receiving rifabutin with lopinavir/ritonavir, and is not expected to be harmful.117,122 These preliminary PK results suggest that rifabutin can be used safely in children >5 years old using rifabutin at 2.5 mg/kg/day with lopinavir/ritonavir, but regular laboratory and clinical monitoring is essential. Younger children are to be investigated in this study to confirm this dosing strategy among all children.

Second-line TB drugs

In children, no research has been conducted to investigate the effect of ART on exposure of medications used for MDR-TB. Potential interaction mechanisms and data from adult studies are described below and grouped by class defined by the WHO MDR-TB treatment guideline.23

Group A

Moxifloxacin undergoes glucuronidation mainly through UGT1A1123 and sulphate conjugation by sulphotransferase, and is a substrate of P-gp. Efavirenz is known to induce UGT, leading to decreased exposure of moxifloxacin in HIV/TB-co-infected adults (AUC0–tau −30%).124 Levofloxacin and ofloxacin are eliminated primarily through glomerular filtration125 and therefore are not expected to interact with ART. Linezolid metabolism is complex, resulting in high interpatient PK variability;126 it undergoes non-CYP-mediated hepatic metabolism into inactive metabolites and is also excreted unchanged in the urine.127 Therefore, DDIs with ARVs are not expected. Linezolid has potential overlapping mitochondrial toxicities, especially with NRTIs, and has a potential increased risk of bone marrow suppression when used with zidovudine.128

Bedaquiline is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 into the less active N-monodesmethyl metabolite (M2),129 and thus is expected to interact with various ARVs via its metabolic pathway. Bedaquiline exposure is significantly decreased when co-administered with efavirenz in healthy and HIV-infected adults,130,131 but no differences in exposure were found in HIV-infected adults receiving nevirapine.132,133 Dose modifications to mitigate the efavirenz–bedaquiline interaction have been simulated; once-daily instead of thrice-weekly administration of bedaquiline or doubling the bedaquiline dose might result in adequate bedaquiline exposure.131 Bedaquiline exposure increased by 22% and that of M2 decreased by 51% when co-administered with lopinavir/ritonavir in HIV/TB-negative adults,129 but this is likely to be an underestimation because the non-compartmental analysis (NCA) did not cover the full AUC of bedaquiline.134 Pandie et al.132 reported increased bedaquiline exposure (+62%) in HIV/TB-co-infected patients receiving lopinavir/ritonavir without concurrent differences in M2 exposure. These DDIs require further investigation in children. Lopinavir/ritonavir might also have an additive or synergistic effect on QT prolongation due to bedaquiline.132 The clinical significance of this DDI is unclear.

Group B

Metabolism of clofazimine has not yet been fully elucidated. Although three clofazimine metabolites have been found in urine after repeated drug administration, it is believed to be mainly excreted unchanged in faeces.135 Terizidone/cycloserine is predominantly excreted renally via glomerular filtration, so few clinically relevant DDIs are expected. Clofazimine and cycloserine can cause neuropsychiatric adverse events, which overlaps with the efavirenz and dolutegravir toxicity profile. Also efavirenz and lopinavir/ritonavir might have an additive effect on clofazimine-induced QT prolongation.128

Group C

Aminoglycosides and carbapenems are not expected to interact with ARVs, since they are renally excreted.136,137 p-Aminosalicylic acid is also mainly excreted renally and to a lesser extent by metabolism through NAT1 and NAT2. Surprisingly, p-aminosalicylic acid clearance was increased by 52% in 19 HIV/TB-co-infected adults using concurrent efavirenz compared with TB-mono-infected or HIV/TB-co-infected patients without efavirenz.138 This potential DDI requires further investigation to determine its mechanism and clinical relevance.

Delamanid is metabolized by albumin into its primary metabolite (DM-6705). Subsequently, CYP3A4 is the main metabolic pathway for DM-6705.139Co-administration of tenofovir disoproxil and efavirenz did not change delamanid exposure in healthy adults, and giving lopinavir/ritonavir resulted in a 25% increase of delamanid AUC0–tau, but this increase was not considered to be clinically relevant.140 Delamanid causes QT prolongation and requires monitoring when used with QT-prolonging ARVs. Ethionamide and prothionamide are interchangeable in MDR-TB treatment regimens and follow a similar metabolic pathway through flavin-containing monooxygenase.141 No DDIs with ART are expected for ethionamide and prothionamide.

Effects of HIV infection on PK of TB drugs

First-line TB drugs

The effect of HIV infection on the PK of TB drugs in children has been examined in multiple studies, but most were inconclusive. It is believed that malabsorption or malnutrition due to HIV infection might cause low exposure to TB treatment in HIV patients.28 Strict mg/kg dosing also contributes greatly to these inconclusive results, since it assumes a linear relationship between body weight and clearance despite the fact that the relationship is more likely to be allometric; not taking a patient’s age into account can result in severe under-dosing, especially in underweight children.142 None of the included studies reported on the impact of ART use or certain antiretroviral agents, because of small sample sizes, heterogeneity in ART or absence of ART, and lack of mechanistic explanations for potential interactions. Hence, it is uncertain whether the observed results are because of HIV infection, ART or differences in the populations. A systematic review was published about the influence of HIV infection on the PK of TB treatment.27 It mainly focused on adults without reporting a comprehensive analysis in children. The authors were unable to generate recommendations with respect to dosing of TB treatment in patients with HIV-associated TB due to heterogeneity and inconsistency of data.27

Results of all studies in children are summarized in Table 2. Apart from two studies reporting a slight decrease of isoniazid Cmax,26,143 most did not find lower isoniazid exposure in children with HIV infection compared with TB-mono-infected children.17,144–149 The overall effect of HIV infection on isoniazid PK seems not to be clinically relevant in children.

Various studies reported lower rifampicin Cmax (range: −17% to −49%) and AUC (range: −24% to −56%) values in children who are HIV/TB co-infected (children both on and off ART) compared with TB-mono-infected children.26,145–147 Rifampicin clearance increased and bioavailability decreased in children with HIV.150 This effect was associated with HIV/TB co-infection rather than the use of ART.150 Other studies did not find statistical differences, probably because of small sample size and limited power. The large decreases in rifampicin exposure can be clinically relevant.

PK data of pyrazinamide in children with HIV and TB compared with HIV-uninfected children was heterogeneous. Some showed a slight decrease in AUC or Cmax144–146 in co-infected children, but most reported varying non-significant results.26,147–149,151 The impact of HIV infection on pyrazinamide PK in children seems relatively small and variable.

Almost all studies investigating ethambutol PK reported lower ethambutol AUC (range: −40% to −60%) and lower ethambutol Cmax (range: −40% to −70%) in children that were HIV infected compared with uninfected children.144–146,148,149 One small study (n = 18) found low ethambutol Cmax values regardless of HIV status.151 Nevertheless, ethambutol exposures generally are substantially lower in HIV-infected children compared with uninfected children. It is unclear whether usage of ART affected PK of ethambutol.

In most studies, children with HIV/TB co-infection had significantly lower weight for age Z-scores due to disease severity or malnutrition. These differences aggravate the assessment of the relationship of lower exposure with HIV/TB co-infection, since lower exposure can partly be explained by relatively higher clearance/kg because of low weight and high fat-free mass. Dosing of TB drugs based on lean body weight might take these issues into account and lead to better exposure in children who are underweight.

Second-line TB drugs

The effect of HIV infection and ART on PK of drugs used for MDR-TB has been investigated in a few studies in children. Only second-line TB drugs that have been studied in children are described here, split by MDR-TB treatment class.

Group A

Exposure of moxifloxacin was found to be significantly lower (AUC0–8h −34%) in children living with HIV using ART [lopinavir/ritonavir- (2/6) or efavirenz-based (4/6) regimen] compared with 17 HIV-uninfected children.152 For levofloxacin and ofloxacin, no significant differences in PK parameters were seen in children with HIV/TB co-infection (both on and off ARVs) compared with children without HIV,153,154 which is consistent with findings in adults.155–157 A population PK study reported a 15.9% reduction in levofloxacin clearance in 16 children with HIV between 0.3 and 8.7 years old receiving ART (lopinavir/ritonavir- or efavirenz-based regimen), but this was not considered clinically relevant.158 One study assessed linezolid PK in children with HIV, but could not detect any effect of HIV infection owing to the small dataset (n = 3).159

Group B

No PK studies have been done for clofazimine and terizidone/cycloserine in children with HIV.

Group C

A non-significant trend towards lower p-aminosalicylic acid exposure was reported in children who were HIV infected (n = 4; all on efavirenz).160 Ethionamide concentrations were found to be significantly lower in children with HIV (n = 7) at both 1 and 4 months after initiation of therapy compared with uninfected peers.161 Bjugard Nyberg et al.162 suggested that ethionamide concentrations were lower because of decreased bioavailability (−21%) in HIV-infected children, of whom most were on ART (efavirenz or lopinavir-based regimen) No significant differences were seen between children receiving lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART, efavirenz-based ART or no ART.162

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first review on the PK of (MDR-)TB drugs and ART in children with HIV-associated TB using a comprehensive systematic and scoping approach. Information from adult studies was also included to identify knowledge gaps and differences between DDIs in children versus adults. This systematic review shows that the number of treatment options is increasing for children with HIV/TB co-infection, but there are still many knowledge gaps when it comes to DDIs between TB drugs and ART. We identified 47 eligible studies; most of them focused on lopinavir/ritonavir, efavirenz, nevirapine and first-line TB treatment.

PK differences between adults and children are common. Differences in membrane permeability, gastric pH and emptying time, plasma protein binding, total body water and fat, organ size, maturation and abundance of metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters, and development of renal function can cause differences in absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) of medications, which changes with age and can affect the severity of DDIs.29,163 The paediatric population itself also consists of multiple subpopulations that have different PK profiles. The FDA distinguishes newborn infants (0–28 days), infants and toddlers (28 days to 2 years), children (2–12 years) and adolescents (12–16 or 18 years). Younger children mainly differ from adults due to immaturity of hepatic enzymes, whereas older children often have increased drug clearance.163 This can result in different recommendations for DDI management. For example, the interaction between rifampicin and lopinavir/ritonavir was found to be different in young children (<3 years old) from that in adults; double-dosing of lopinavir/ritonavir resulted in adequate lopinavir concentrations in adults, but led to subtherapeutic concentrations in children.100 There were no data to confirm these differences in older children. Another example is the interaction between rifampicin and raltegravir. Doubling the dose of raltegravir q12h was needed to overcome the interaction with rifampicin in children,45 whereas exposure in adults seemed therapeutic when using normally dosed raltegravir q12h.42 These examples illustrate that DDIs and strategies to overcome DDIs should preferably be tested in children from all different paediatric subpopulations before adult recommendations can be extrapolated. Different formulations given to children can also influence PK of drugs; for example, sorbitol (as excipient) affects absorption of lamivudine.164,165 In addition, data on pharmacodynamic differences in the paediatric population compared with adults and their impact on DDI management are scarce, and this requires further investigation.

Extrapolation of adult PK data by means of population PK modelling offers a great opportunity to identify new treatment strategies to avoid toxicity or suboptimal therapy due to DDIs in children. However, conducting confirmatory PK studies remains essential in assessing the magnitude of DDIs in children. Extrapolating double-dosed lopinavir/ritonavir with concomitant rifampicin-based TB treatment from adults on solid formulation to young children on liquid formulation could not be confirmed in clinical studies. Physiologically based PK models can help to better characterize these complicated interactions and improve predictions of dosing regimens appropriate to overcome DDIs in children.166