Summary

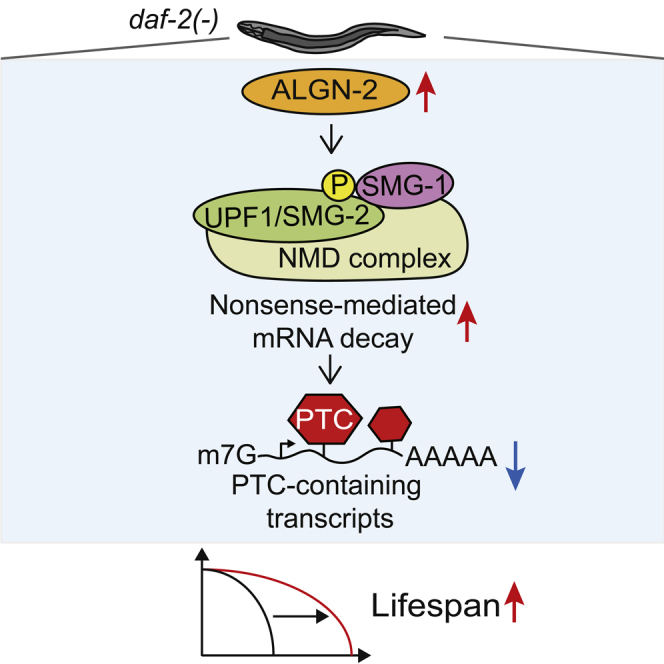

Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) is a biological surveillance mechanism that eliminates mRNA transcripts with premature termination codons. In Caenorhabditis elegans, NMD contributes to longevity by enhancing RNA quality. Here, we aimed at identifying NMD-modulating factors that are crucial for longevity in C. elegans by performing genetic screens. We showed that knocking down each of algn-2/asparagine-linked glycosylation protein, zip-1/bZIP transcription factor, and C44B11.1/FAS apoptotic inhibitory molecule increased the transcript levels of NMD targets. Among these, algn-2 exhibited an age-dependent decrease in its expression and was required for maintaining normal lifespan and for longevity caused by various genetic interventions. We further demonstrated that upregulation of ALGN-2 by inhibition of daf-2/insulin/IGF-1 receptor contributed to longevity in an NMD-dependent manner. Thus, algn-2, a positive regulator of NMD, plays a crucial role in longevity in C. elegans, likely by enhancing RNA surveillance. Our study will help understand how NMD-mediated mRNA quality control extends animal lifespan.

Subject Areas: Genetics, Molecular Biology, Cell Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

C. elegans algn-2 is a positive regulator of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD)

-

•

algn-2 is downregulated during aging and contributes to maintaining normal lifespan

-

•

algn-2 is required for longevity caused by various genetic interventions

-

•

Upregulation of ALGN-2 by inhibition of daf-2 promotes longevity via increasing NMD

Genetics; Molecular Biology; Cell Biology

Introduction

Eukaryotic cells are equipped with mechanisms that maintain proper gene expression and prevent the production of deleterious proteins. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) is an mRNA quality control mechanism that monitors and degrades abnormal transcripts with premature termination codons (PTCs) (He and Jacobson, 2015; Kim and Maquat, 2019; Kurosaki et al., 2019). NMD targets also include mRNAs with long (>1 kb) 3′ untranslated regions, upstream open reading frames, or selenocysteine-encoding UGA codons (He and Jacobson, 2015; Kim and Maquat, 2019; Kurosaki et al., 2019). Thus, NMD is crucial for RNA quality surveillance and the maintenance of the correct transcriptome in organisms.

Key evolutionarily conserved components of NMD have been identified by using model organisms, including the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. A genetic screen using C. elegans has identified the main NMD components, smg (suppressor with morphological effect on genitalia)-1 through smg-7 (Hodgkin et al., 1989; Mango, 2001). SMG-1 is a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-related kinase that phosphorylates SMG-2/UPF1 RNA helicase (Hodgkin et al., 1989; Mango, 2001). This event activates the NMD machinery and leads to the cleavage of target mRNAs via the endonuclease SMG-6 (Eberle et al., 2009; Huntzinger et al., 2008; Lykke-Andersen et al., 2014). Subsequently, the target mRNAs are degraded by exosomes and exonucleases (Schmid and Jensen, 2008). Additional research has led to the discovery of other NMD components, including smg-8, smg-9, smgl (smg lethal)-1, and smgl-2 (Longman et al., 2007; Yamashita et al., 2009); however, the role of smg-8 in NMD has been challenged by the characterization of smg-8 mutants (Rosains and Mango, 2012). Unlike the abovementioned, extensively characterized NMD components, the upstream regulators of NMD remain underexplored.

In C. elegans, NMD contributes to longevity by influencing the levels of various mRNAs (Son et al., 2017). Specifically, NMD function is crucial for extended lifespan conferred by reduced insulin/IGF-1 signaling (IIS), an evolutionarily conserved aging-regulatory pathway. Reduced IIS increases NMD and subsequently decreases the levels of specific transcripts, including yars-2b.1/tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase isoform b.1, and this, in turn, contributes to longevity. In addition, NMD is upregulated to modulate the splicing of various gene transcripts that are important for dietary restriction-induced longevity (Tabrez et al., 2017). Despite these initial findings on the roles of the known NMD components in longevity in C. elegans, it remains poorly understood whether and how NMD contributes to extended lifespan and delayed aging.

In the present report, we identified modulators of NMD by employing two genetic screens. We first performed a genome-wide RNAi screen for the modifiers of NMD by using a fluorescent NMD reporter and subsequently validated the results by measuring the level of rpl-7A, an endogenous NMD target transcript. We found that RNAi targeting each of algn-2/asparagine-linked glycosylation protein, zip-1/bZIP transcription factor, and C44B11.1/FAS apoptotic inhibitory molecule (FAIM) increased the levels of the rpl-7A transcript. We also showed that two of the mutants isolated from our mutagenesis screen exhibited decreased rpl-7A transcript levels. We then found that algn-2, the expression of which declined during aging, was required for maintaining the normal lifespan. Furthermore, we showed that knocking down algn-2 significantly decreased the longevity conferred by various genetic interventions, including daf-2/insulin/IGF-1 receptor mutations, dietary restriction mimetic eat-2 mutations, and mitochondrial respiration-defective isp-1 mutations. We further showed that ALGN-2 was upregulated upon the genetic inhibition of the daf-2/insulin/IGF-1 receptor and contributed to a long lifespan in an SMG-2-dependent manner. Overall, our study identified previously unknown modulators of NMD, including algn-2, which plays key roles in RNA quality control and organismal longevity.

Results

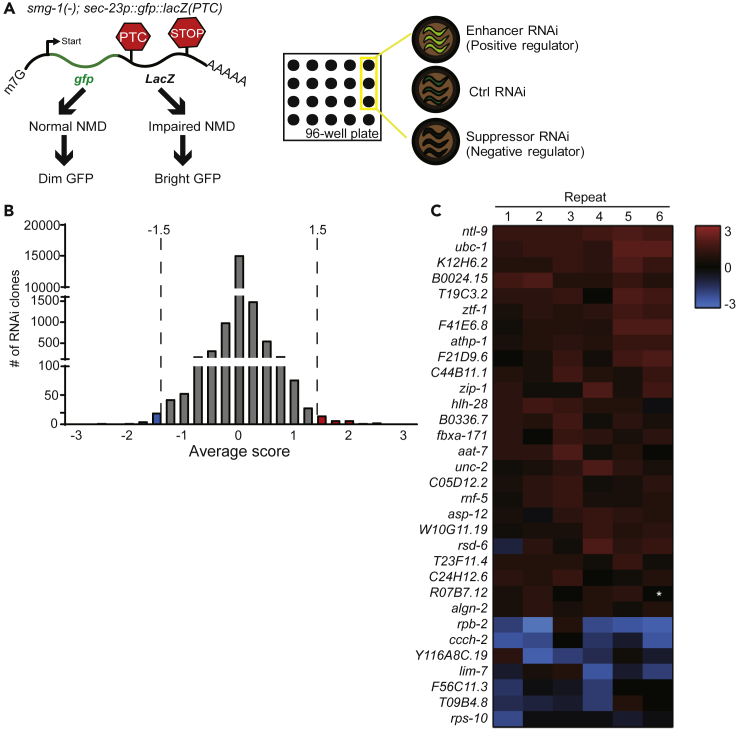

A Genome-wide RNAi Screen Identified Modifiers of NMD

To identify NMD regulators, we first performed a genome-wide RNAi screen in a liquid culture system using an NMD-responsive GFP reporter (Figure 1A). The NMD reporter contains a PTC in the first exon of the GFP-fused lacZ gene, driven by a ubiquitous sec-23 promoter, sec-23p::gfp::lacZ(PTC) (Longman et al., 2007) (Figure 1A). Under normal conditions, this transcript is degraded by NMD, and the worms, therefore, display dim GFP fluorescence (Figure 1A). We used a sensitized loss-of-function mutant background of smg-1, which encodes a kinase that phosphorylates SMG-2/UPF1 and induces NMD (Grimson et al., 2004). With the increased basal GFP expression of the reporter in the smg-1(−) mutant background, we searched for genes whose knockdown further changed the green fluorescence intensity (Figure 1A). We initially found that the GFP expression levels were further increased by 39 RNAi clones and decreased by 38 RNAi clones (arbitrary cutoff: > 1.5 and −1.5 <, Figure 1B and Table S1). By repeating the experiments six times, we confirmed that 25 and 7 RNAi clones increased and decreased the GFP levels, respectively (cutoff of mean value: > 0.6 and −0.6 <, Figure 1C and Table S1).

Figure 1.

A Genome-wide RNAi Screen for NMD Modulators

(A) Schematic showing a PTC-bearing gfp-lacZ transgene in a smg-1(tm849) [smg-1(−)] mutant background [smg-1(−); sec-23p::gfp::lacZ(PTC)], which was used as a reporter for a genome-wide RNAi screen in a liquid culture system (score range: −3 to +3). gfp RNAi and control RNAi (Ctrl) were used as controls to provide references for scores −3 and 0, respectively.

(B) Summary of initial genome-wide RNAi screen data (arbitrary cutoff scores: < −1.5 and >1.5).

(C) The assay was repeated for RNAi clones that passed the cutoff of the initial screen six times, and the average scores from the six experiments were used to narrow down the candidates (mean cutoff scores: < −0.6 and >0.6). Twenty-five and seven RNAi clones increased and decreased the GFP level of the reporter, respectively. Asterisk (∗) indicates lack of data because worms were not placed in the designated well. See Table S1 for the descriptions and scores of indicated RNAi clones from the screen.

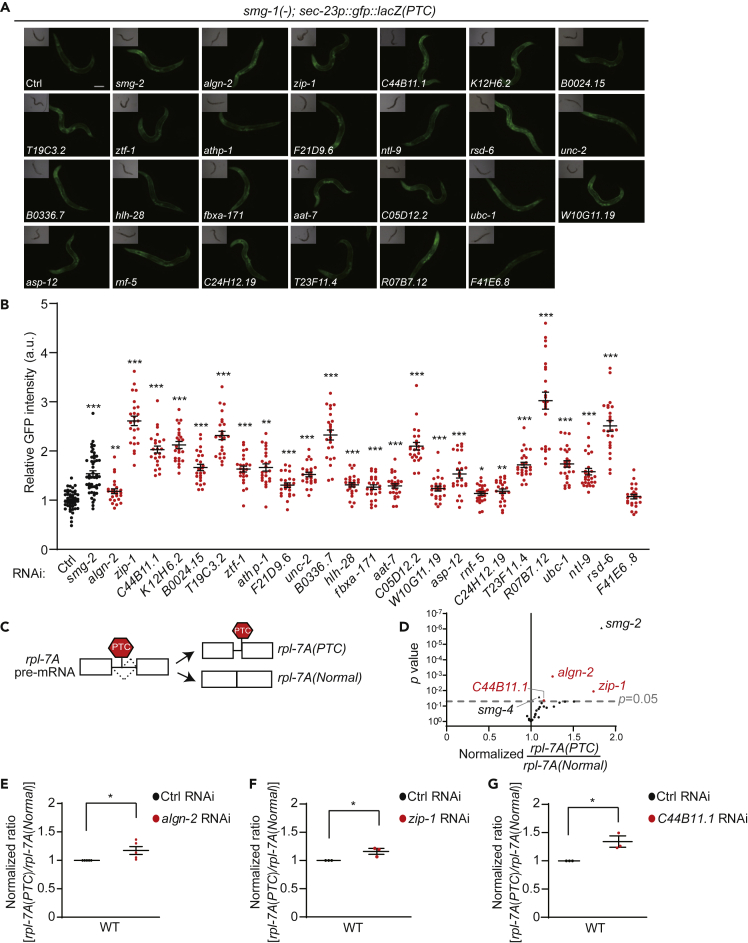

RNAi Targeting algn-2, zip-1, or C44B11.1 Increased the Level of an NMD Target Transcript, rpl-7A(PTC)

We then validated the RNAi clones from our liquid culture-based screen by using a solid-medium culture system. We found that 24 of the 25 RNAi clones that increased the GFP levels in liquid culture did the same on solid media (Figures 2A and 2B, Table S1). However, none of the seven RNAi clones that decreased the GFP levels in liquid culture did on solid media (Figures S1A and S1B, Table S1). We further determined the effects of our hit RNAi clones on an endogenous NMD target gene, rpl-7A(PTC) (Mitrovich and Anderson, 2000) (Figure 2C and Table S1). We found that RNAi knockdown of algn-2, zip-1, or C44B11.1 significantly increased the level of the rpl-7A(PTC) transcript in smg-1(−) mutants as well as in wild-type animals (Figures 2D–2G, Table S1). Thus, algn-2, zip-1, and C44B11.1 appear to be positive modulators of NMD.

Figure 2.

Validation of NMD Modulators Identified from Genome-wide RNAi Screen

(A) Representative RNAi clones targeting potential NMD regulators on solid media. Of 25 potential positive NMD regulators identified from the genome-wide RNAi screen, 24 increased the GFP expression level on solid culture media (scale bar, 100 μm). Ctrl, control RNAi. smg-2 RNAi was used as a positive control.

(B) Quantification data for panel (A). Error bars represent SEM (two-tailed Student's t test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, n ≥ 24 from three independent experiments). See Table S1 for the relative GFP level change caused by treating with each RNAi clone.

(C) Schematic diagram showing the alternative splicing of rpl-7A that generates rpl-7A(Normal), a normal transcript, and rpl-7A(PTC), an established NMD target transcript.

(D) Volcano plot showing normalized rpl-7A(PTC) level and p values from RT-PCR in smg-1(tm849) mutants with each of the RNAi clones. p values were calculated using a two-tailed Student's t test. A dotted line indicates p = 0.05, and black triangles indicate smg-2 RNAi and smg-4 RNAi, which were used as positive controls. See Table S1 for the normalized rpl-7A(PTC) ratio for the indicated RNAi clones and Figure S1 legends for discussion regarding (B and D).

(E–G) Normalized rpl-7A(PTC) level obtained from qRT-PCR in wild-type (WT) worms treated with algn-2 RNAi (n = 5) (E), zip-1 RNAi (n = 3) (F), and C44B11.1 RNAi (n = 3) (G). Error bars represent SEM (two-tailed Student's t test, ∗p < 0.05).

An EMS Mutagenesis Screen Identified Potential Negative Modulators of NMD

Because we were not able to identify RNAi clones that reliably decreased the NMD reporter GFP level from our genome-wide RNAi screen (Figure S1), we sought to identify such genetic inhibition by employing an EMS mutagenesis screen (Figure S3A). From the 83,400 mutagenized haploid genomes of smg-1(−); sec-23p::gfp::lacZ(PTC) animals, we obtained 11 and 9 fertile mutant strains with decreased and increased GFP levels, respectively (Figure S3A). We then confirmed the reproducibility of the results by quantifying the fluorescence levels of the mutants (Figure S3B). Because of the absence of screened RNAi clones that reproducibly decreased the NMD reporter GFP level, we focused on potential negative NMD regulator mutants. Among the 11 mutants that displayed reduced NMD reporter GFP levels, we found that two mutant alleles, yh47 and yh57, significantly decreased the level of the rpl-7A(PTC) transcript using qRT-PCR (Figure S3C). These data suggest that genes that are mutated by yh47 and yh57 alleles encode potential negative regulators of NMD.

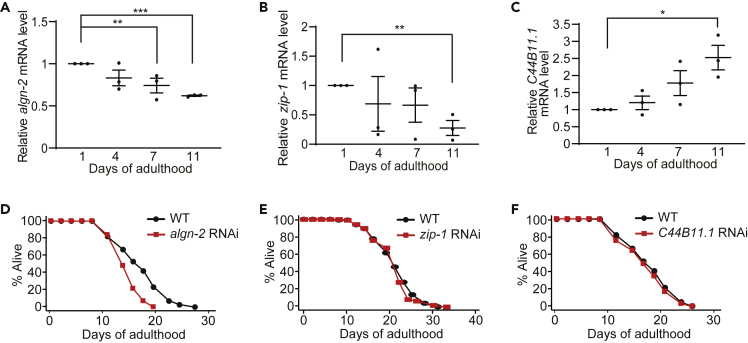

algn-2 Whose mRNA Level Decreases with Age Is Required for Maintaining the Normal Lifespan

We previously reported that NMD function decreases with age and mediates longevity conferred by reduced IIS in C. elegans (Son et al., 2017). Thus, in the present study, we tested whether algn-2, zip-1, or C44B11.1 exhibited age-dependent expression changes or contributed to longevity. We found that the mRNA levels of algn-2 and zip-1 decreased with age, whereas that of C44B11.1 exhibited an age-dependent increase (Figures 3A–3C). These data imply a functional association between algn-2, zip-1, or C44B11.1 and aging in C. elegans. We then determined whether RNAi targeting each of algn-2, zip-1, and C44B11.1 affected lifespan. We found that algn-2 RNAi significantly shortened the lifespan of wild-type animals, whereas zip-1 RNAi or C44B11.1 RNAi did not (Figures 3D–3F). Thus, algn-2, which exhibits an age-dependent decrease in mRNA levels, is required for the maintenance of the normal lifespan.

Figure 3.

Age-Dependent Expression Changes in algn-2, zip-1, and C44B11.1, and Their Functions in Lifespan

(A–C) mRNA levels of algn-2 (A), zip-1 (B), and C44B11.1 (C) in day 1, 4, 7, and 11 adult wild-type worms analyzed by using qRT-PCR (n = 3). Error bars represent SEM (two-tailed Student's t test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). See Figure S4 legends for discussion regarding the expression changes in C44B11.1.

(D–F) RNAi targeting algn-2 significantly reduced the lifespan of wild-type (WT) animals (D), but RNAi targeting zip-1 (E) or C44B11.1 (F) did not. algn-2 RNAi, zip-1 RNAi, and C44B11.1 RNAi significantly decreased the mRNA levels of algn-2, zip-1, and C44B11.1, respectively (Figures S2A, S2C, and S2D). See Table S3 for statistical analysis and additional lifespan data.

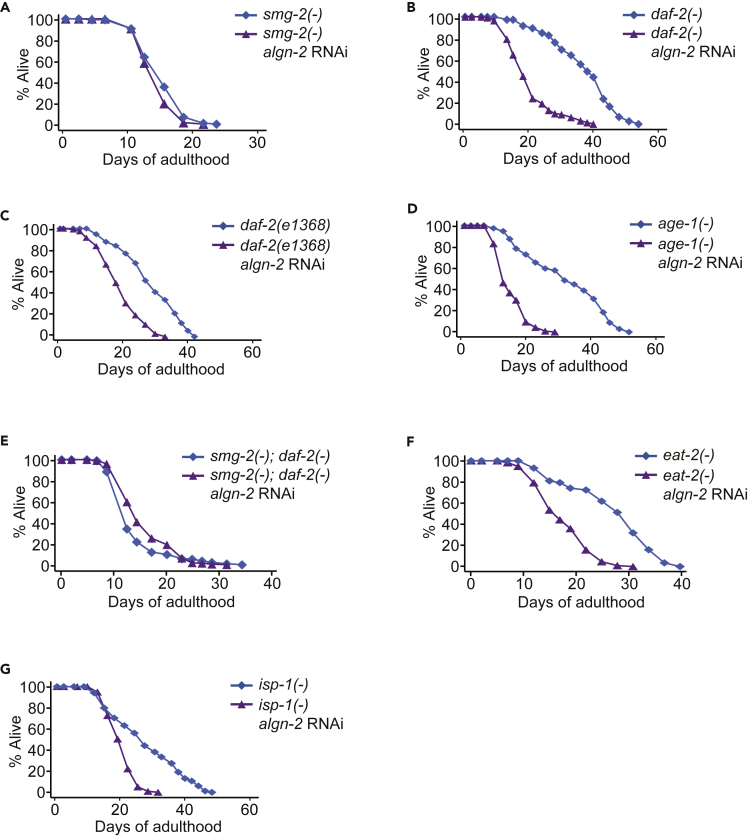

algn-2 Is Crucial for Longevity Conferred by Various Interventions, including daf-2/Insulin/IGF-1 Receptor Mutations that Enhance NMD

Next, we focused our functional analysis on the role of algn-2 in the lifespan. We showed that algn-2 RNAi did not further decrease short lifespan caused by mutations in smg-2 (Figure 4A). Thus, algn-2 appears to act together with SMG-2 to maintain normal lifespan in C. elegans. We have previously reported that SMG-2, an RNA helicase essential for NMD (Kim and Maquat, 2019; Page et al., 1999), is critical for C. elegans longevity resulting from reduced IIS, which increases NMD (Son et al., 2017). We therefore tested whether algn-2 contributed to the longevity conferred by reduced IIS. We found that algn-2 RNAi significantly decreased the long lifespan conferred by two mutant alleles of daf-2/insulin/IGF-1 receptor gene, e1370 and e1368 (Figures 4B and 4C), or a phosphoinositide-3 kinase gene mutation, age-1(hx546) (Figure 4D). In addition, algn-2 RNAi did not further decrease the shortened lifespan of smg-2(−); daf-2(−) mutants (Figure 4E). These results suggest that algn-2 contributes to longevity conferred by reduced insulin/IGF-1 signaling by acting together with SMG-2.

Figure 4.

algn-2 Contributes to Longevity Conferred by Various Interventions, including Reduced Insulin/IGF-1 Signaling by Acting Together with SMG-2

(A) algn-2 RNAi did not decrease the lifespan of smg-2(qd101) [smg-2(−)] mutants.

(B–D) RNAi targeting algn-2 significantly decreased the long lifespan of daf-2(e1370) [daf-2(−)] (B), daf-2(e1368) (C), and age-1(hx546) [age-1(−)] (D) mutants. Different from algn-2 RNAi, neither zip-1 RNAi nor C44B11.1 affected the lifespan of daf-2(−) mutants (Figures S4A and S4B).

(E) algn-2 RNAi had a small effect on the lifespan of smg-2(−); daf-2(−) double mutants. algn-2 mRNA levels were not changed by smg-2(−) or daf-2(−) mutations (Figure S2B).

(F and G) algn-2 RNAi shortened longevity induced by eat-2(ad1116) [eat-2(−)] (F) and isp-1(qm150) [isp-1(−)] (G) mutations. See Table S3 for statistical analysis and additional lifespan data.

We also tested the effect of algn-2 RNAi on the longevity of dietary restriction mimetic eat-2(−) mutants and mitochondrial respiration-defective isp-1(−) mutants. We found that RNAi knockdown of algn-2 significantly shortened the long lifespan of eat-2(−) mutants (Figure 4F) and isp-1(−) mutants (Figure 4G). These data indicate that algn-2 is generally required for lifespan extension caused by various interventions in C. elegans.

Genetic Inhibition of daf-2 Upregulates ALGN-2 to Increase NMD Function and Lifespan

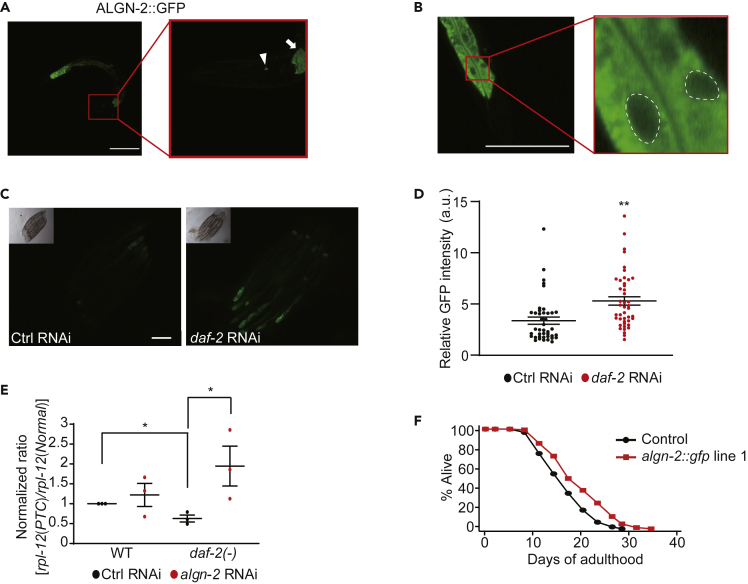

We next generated transgenic animals expressing GFP-fused ALGN-2 under the promoter of algn-2 (algn-2p::algn-2::gfp) and detected ALGN-2::GFP in the intestine and neurons (Figure 5A). We showed that ALGN-2::GFP was localized in the cytoplasm of the cells (Figure 5B), consistent with the localization of mammalian ALG2, the ALGN-2 ortholog, on the cytosolic face of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Dean and Gao, 2014).

Figure 5.

algn-2 Is Upregulated by the Genetic Inhibition of daf-2 for Enhancing NMD Function and Sufficient to Increase Lifespan

(A) Images of algn-2::gfp-expressing transgenic animals. The image in the red box focusing on the head region of the same worm on the left was obtained by using high magnification (scale bar, 100 μm) (arrow: intestine, arrowhead: neurons).

(B) The intestinal region of algn-2::gfp-expressing transgenic animals obtained by using a confocal microscope (scale bar, 100 μm). The image in the red box is enlarged from the indicated region on the left. Areas in white dashed lines indicate the nuclei.

(C) The images of algn-2::gfp worms treated with control (Ctrl) RNAi and daf-2 RNAi (scale bar, 100 μm).

(D) Quantification of ALGN-2:GFP levels in (C). Error bars represent SEM (two-tailed Student's t-test, ∗∗p < 0.01, n = 40 from three independent experiments).

(E) The effect of daf-2(−) mutation and algn-2 RNAi on the expression level of rpl-12(PTC) measured by using qRT-PCR (n = 3). Error bars represent SEM (two-tailed Student's t test, ∗p < 0.05).

(F) algn-2::gfp line 1 (yhEx540[algn-2p::algn-2::gfp; ofm-1p::rfp]) increased the lifespan of control (ofm-1p::rfp) worms. See Table S3 for statistical analysis and additional lifespan data.

We then examined whether the genetic inhibition of daf-2 affected the level of ALGN-2. Interestingly, daf-2 RNAi significantly increased the level of ALGN-2::GFP (Figures 5C and 5D), without affecting that of algn-2 mRNA (Figure S2B), suggesting that reduced insulin/IGF-1 signaling upregulates ALGN-2 at the post-transcriptional level. Next, we determined whether algn-2 affected NMD function in daf-2(−) mutants. Specifically, we measured the level of rpl-12(PTC) transcript, an endogenous NMD target whose level decreases in daf-2(−) mutants and increases with age (Mitrovich and Anderson, 2000; Son et al., 2017) (Figure 5E). We showed that algn-2 RNAi substantially increased the rpl-12(PTC) level in daf-2(−) mutants (Figure 5E). Together, these data suggest that upregulation of ALGN-2 conferred by reduced insulin/IGF-1 signaling enhances NMD in C. elegans.

Lastly, we tested whether the transgenic overexpression of algn-2::gfp affected lifespan. We found that the transgene that expressed algn-2::gfp at the highest level among three lines (Figures S5A and S5B) significantly increased lifespan (Figure 5F), whereas the other two did not (Figure S5C). Together, these data suggest that upregulation of ALGN-2 can increase lifespan by enhancing NMD.

Discussion

ALGN-2, an NMD Modulator, Contributes to Longevity in C. elegans

NMD is an evolutionarily conserved process that is crucial for the monitoring and maintenance of RNA quality and, therefore, cellular RNA homeostasis. In the present report, we performed a series of genetic screens to identify modifiers of NMD. From our genome-wide RNAi screen, we identified algn-2, zip-1, and C44B11.1/FAIM as NMD modulators that were required for downregulation of NMD target transcripts. Among these, we showed that algn-2 contributed to longevity conferred by daf-2/insulin/IGF-1 receptor mutations in an NMD-dependent manner. Our study highlights the power of genetic screens for identifying factors that regulate NMD function and thereby affect organismal lifespan, possibly through the maintenance of RNA quality.

ALGN-2 May Affect NMD Function by Regulating the ER Stress Response

ALG2, the mammalian ortholog of ALGN-2, is a mannosyltransferase located at the ER membrane (Dean and Gao, 2014). ALG2 catalyzes the second and third mannosylation steps, which convert guanosine diphosphate mannose to core asparagine (N)-glycan (Li et al., 2019). Immature glycosylation causes severe ER stress, resulting in the activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) (Cherepanova et al., 2016). ER stress can inhibit NMD and causes the NMD complex to be localized to the ER (Sakaki et al., 2012; Usuki et al., 2019). algn-2 RNAi also increases ER stress in C. elegans (Akiyoshi et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2019) and may therefore decrease NMD by altering ER stress responses. In addition, defects in N-linked glycosylation pathway genes, including ALG2, are linked to congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS), which involves the impairment of signal transmission at neuromuscular synapses (Cossins et al., 2013; Engel, 2018). Interestingly, NMD is impaired in some types of CMS (Rahman and Nasrin, 2016), suggesting that ALG2-regulated NMD processes play a role in the pathophysiology of CMS. Further studies are required to dissect the mechanisms by which inhibition of algn-2 affects the pathophysiology of the disease and NMD function potentially through affecting ER stress.

algn-2 Upregulates NMD in an SMG-2-Dependent Manner

One interesting aspect of our study is that we identified algn-2 from an RNAi screen that used an NMD reporter in a smg-1 mutant background. Interestingly, we found that algn-2 RNAi did not affect the lifespan of smg-2 mutants. Our previous report on NMD and longevity (Son et al., 2017) indicates that different SMG components differentially contribute to NMD function. Specifically, knockdown of smg-1 has an intermediate effect on NMD function among five smg genes that we functionally tested. In contrast, smg-2 RNAi has the biggest effect on NMD function. These data suggest that genetic inhibition of smg-2 causes more severe impacts on NMD function than that of smg-1 does. Thus, we speculate that algn-2 RNAi did not further decrease the lifespan of smg-2(−) animals, while influencing NMD target levels in smg-1(−) mutants, because of their differential effects on NMD functions.

NMD-Regulated RNA Quality Control Is Crucial for Organismal Longevity

Recent reports indicate that NMD-mediated RNA homeostasis is critical for longevity in C. elegans (Son et al., 2017; Tabrez et al., 2017). These studies highlight the importance of NMD for clearing abnormal transcripts and promoting RNA homeostasis, which may help animals maintain health during aging. However, it remained unknown which factor causes a functional decline of NMD during aging. Our data suggest that reduced levels of factors that regulate NMD, including algn-2, underlie age-dependent decreases in NMD and possibly result in impaired RNA quality control. Our previous reports have also indicated that the NMD in the nervous system is crucial for lifespan extension (Son et al., 2017). Because the brain is the organ that expresses Alg2 at the highest level in young mice (Imamura et al., 2014), Alg2 expression in the brain may decrease in an age-dependent manner, perhaps contributing to the shortening of the lifespan by reducing NMD efficiency. It will be interesting to test whether preserving or increasing the levels of positive NMD modulators, including ALG2/ALGN-2, can be exploited as a strategy for avoiding the adverse effects of age-dependent declines in RNA quality, in particular in the nervous systems.

Limitations of the Study

Although we identified algn-2 as a positive regulator of NMD, which contributed to longevity in C. elegans, the biochemical mechanisms by which ALGN-2 affects NMD functions remain elusive. In addition, global transcriptomic analysis will help identify all the target transcripts of algn-2. Although we showed that decreased NMD function due to smg-1(−) was suppressed by yh47 and yh57, two mutant alleles that we identified from our mutagenesis screen, the molecular identities of the mutations are unknown. Additionally, we did not test whether algn-2 modulated NMD in a cell autonomous or a cell non-autonomous manner. These are important issues that need to be addressed in future studies.

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further request and information for resources and reagents used in this published article should be directed and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Seung-Jae V. Lee (seungjaevlee@kaist.ac.kr).

Materials Availability

All data analyzed and generated in this research are included in this published article and supplemental information.

Data and Code Availability

The published article includes all data generated in this study.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank all Lee lab members for help and discussion. This study is supported by the Korean Government (MSICT) through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Korea (NRF-2019R1A3B2067745) to S-J.V.L.

Author Contributions

E.J.E.K., H.G.S., H.-E.H.P, Y.J., S.K., and S.-J.V.L designed the experiments. E.J.E.K., H.G.S., H.-E.H.P, Y.J., and S.K. performed the experiments. E.J.E.K. and S.-J.V.L. analyzed the data. E.J.E.K. and S.-J.V.L. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: November 20, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101713.

Supplemental Information

Seventy-seven hit RNAi clones (arbitrary cutoff: > 1.5 and −1.5 <) from our whole genome RNAi screen (Figure 1A). RNAi clones that increased and decreased the GFP levels of smg-1(tm849); sec-23p::gfp::lacZ(PTC) were divided by a bold dashed line. RNAi clones with gray shade did not pass the cutoff from the hexaplicate confirmation experiments (cutoff of mean value: > 0.6 and −0.6 <). ∗ indicates positive control.

smg-1(tm849) I; PTCxi::GFP transgenic worms (P0) treated with EMS from two trials (trial 1 and trial 2). Plate numbers are indicated to track isolated mutants from P0 and F1 worms. Among 98 F2 mutants that we initially isolated from 83,400 mutagenized haploid genomes, 35 and 15 mutants that, respectively, displayed increased and decreased GFP levels were sterile, and 19 and 9 mutants that, respectively, increased and decreased GFP mutants initially did not exhibit reproducible phenotypes. Nine and eleven fertile mutants reproducibly displayed increased and decreased GFP levels, respectively (Figures 3A and 3B).

Lifespan data from the same sets were within the double lines, and biological repeats were divided by bold dashed lines. All p values were calculated by using a log rank test. Percent (%) changes and p values indicate comparison between each condition with control RNAi within the same experimental sets. smg−2: % changes and p values calculated against smg-2(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. daf−2: % changes and p values calculated against daf-2(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. smg−2; daf−2: % changes and p values calculated against smg-2(−); daf-2(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. age−1: % changes and p values calculated against age-1(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. eat−2: % changes and p values calculated against eat-2(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. isp−1: % changes and p values calculated against isp-1(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. “Figures in text” indicates lifespan dataset that was used in indicated figures.

References

- Akiyoshi S., Nomura K.H., Dejima K., Murata D., Matsuda A., Kanaki N., Takaki T., Mihara H., Nagaishi T., Furukawa S. RNAi screening of human glycogene orthologs in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and the construction of the C. elegans glycogene database. Glycobiology. 2015;25:8–20. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwu080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanova N., Shrimal S., Gilmore R. N-linked glycosylation and homeostasis of the endoplasmic reticulum. Curr. Opin. Cel. Biol. 2016;41:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossins J., Belaya K., Hicks D., Salih M.A., Finlayson S., Carboni N., Liu W.W., Maxwell S., Zoltowska K., Farsani G.T. Congenital myasthenic syndromes due to mutations in ALG2 and ALG14. Brain. 2013;136:944–956. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean N., Gao X.-D. Heterodimeric Alg13/Alg14 UDP-GlcNAc transferase (ALG13,14) In: Taniguchi N., Honke K., Fukuda M., Narimatsu H., Yamaguchi Y., Angata T., editors. Handbook of Glycosyltransferases and Related Genes. Springer Japan; 2014. pp. 1231–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Eberle A.B., Lykke-Andersen S., Mühlemann O., Jensen T.H. SMG6 promotes endonucleolytic cleavage of nonsense mRNA in human cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel A.G. Congenital myasthenic syndromes in 2018. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2018;18:46. doi: 10.1007/s11910-018-0852-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimson A., O'Connor S., Newman C.L., Anderson P. SMG-1 is a phosphatidylinositol kinase-related protein kinase required for nonsense-mediated mRNA Decay in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:7483–7490. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7483-7490.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F., Jacobson A. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: degradation of defective transcripts is only part of the story. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2015;49:339–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-112414-054639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho N., Wu H., Xu J., Koh J.H., Yap W.S., Goh W.W.B., Chong S.C., Taubert S., Thibault G. ER stress sensor Ire1 deploys a divergent transcriptional program in response to lipid bilayer stress. bioRxiv. 2019:774133. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201909165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J., Papp A., Pulak R., Ambros V., Anderson P. A new kind of informational suppression in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1989;123:301–313. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.2.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger E., Kashima I., Fauser M., Saulière J., Izaurralde E. SMG6 is the catalytic endonuclease that cleaves mRNAs containing nonsense codons in metazoan. RNA. 2008;14:2609–2617. doi: 10.1261/rna.1386208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura K., Maeda S., Kawamura I., Matsuyama K., Shinohara N., Yahiro Y., Nagano S., Setoguchi T., Yokouchi M., Ishidou Y. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enhancer-binding protein 3 is essential for the expression of asparagine-linked glycosylation 2 in the regulation of osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:9865–9879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.520585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.K., Maquat L.E. UPFront and center in RNA decay: UPF1 in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and beyond. RNA. 2019;25:407–422. doi: 10.1261/rna.070136.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki T., Popp M.W., Maquat L.E. Quality and quantity control of gene expression by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:406–420. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.-T., Lu T.-T., Xu X.-X., Ding Y., Li Z., Kitajima T., Dean N., Wang N., Gao X.-D. Reconstitution of the lipid-linked oligosaccharide pathway for assembly of high-mannose N-glycans. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1813. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longman D., Plasterk R.H., Johnstone I.L., Cáceres J.F. Mechanistic insights and identification of two novel factors in the C. elegans NMD pathway. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1075–1085. doi: 10.1101/gad.417707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykke-Andersen S., Chen Y., Ardal B.R., Lilje B., Waage J., Sandelin A., Jensen T.H. Human nonsense-mediated RNA decay initiates widely by endonucleolysis and targets snoRNA host genes. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2498–2517. doi: 10.1101/gad.246538.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mango S.E. Stop making nonSense: the C. elegans smg genes. Trends Genet. 2001;17:646–653. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02479-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrovich Q.M., Anderson P. Unproductively spliced ribosomal protein mRNAs are natural targets of mRNA surveillance in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2173–2184. doi: 10.1101/gad.819900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M.F., Carr B., Anders K.R., Grimson A., Anderson P. SMG-2 is a phosphorylated protein required for mRNA surveillance in Caenorhabditis elegans and related to Upf1p of yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:5943–5951. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M., Nasrin F. Human disease-causing mutations affecting RNA splicing and NMD. J. Investig. Genomics. 2016;3:00046. [Google Scholar]

- Rosains J., Mango S.E. Genetic characterization of smg-8 mutants reveals no role in C. elegans nonsense mediated decay. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaki K., Yoshina S., Shen X., Han J., DeSantis M.R., Xiong M., Mitani S., Kaufman R.J. RNA surveillance is required for endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2012;109:8079–8084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110589109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M., Jensen T.H. The exosome: a multipurpose RNA-decay machine. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008;33:501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son H.G., Seo M., Ham S., Hwang W., Lee D., An S.W., Artan M., Seo K., Kaletsky R., Arey R.N. RNA surveillance via nonsense-mediated mRNA decay is crucial for longevity in daf-2/insulin/IGF-1 mutant C. elegans. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14749. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabrez S.S., Sharma R.D., Jain V., Siddiqui A.A., Mukhopadhyay A. Differential alternative splicing coupled to nonsense-mediated decay of mRNA ensures dietary restriction-induced longevity. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:306. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00370-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuki F., Yamashita A., Fujimura M. Environmental stresses suppress nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) and affect cells by stabilizing NMD-targeted gene expression. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1279. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38015-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita A., Izumi N., Kashima I., Ohnishi T., Saari B., Katsuhata Y., Muramatsu R., Morita T., Iwamatsu A., Hachiya T. SMG-8 and SMG-9, two novel subunits of the SMG-1 complex, regulate remodeling of the mRNA surveillance complex during nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1091–1105. doi: 10.1101/gad.1767209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Seventy-seven hit RNAi clones (arbitrary cutoff: > 1.5 and −1.5 <) from our whole genome RNAi screen (Figure 1A). RNAi clones that increased and decreased the GFP levels of smg-1(tm849); sec-23p::gfp::lacZ(PTC) were divided by a bold dashed line. RNAi clones with gray shade did not pass the cutoff from the hexaplicate confirmation experiments (cutoff of mean value: > 0.6 and −0.6 <). ∗ indicates positive control.

smg-1(tm849) I; PTCxi::GFP transgenic worms (P0) treated with EMS from two trials (trial 1 and trial 2). Plate numbers are indicated to track isolated mutants from P0 and F1 worms. Among 98 F2 mutants that we initially isolated from 83,400 mutagenized haploid genomes, 35 and 15 mutants that, respectively, displayed increased and decreased GFP levels were sterile, and 19 and 9 mutants that, respectively, increased and decreased GFP mutants initially did not exhibit reproducible phenotypes. Nine and eleven fertile mutants reproducibly displayed increased and decreased GFP levels, respectively (Figures 3A and 3B).

Lifespan data from the same sets were within the double lines, and biological repeats were divided by bold dashed lines. All p values were calculated by using a log rank test. Percent (%) changes and p values indicate comparison between each condition with control RNAi within the same experimental sets. smg−2: % changes and p values calculated against smg-2(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. daf−2: % changes and p values calculated against daf-2(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. smg−2; daf−2: % changes and p values calculated against smg-2(−); daf-2(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. age−1: % changes and p values calculated against age-1(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. eat−2: % changes and p values calculated against eat-2(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. isp−1: % changes and p values calculated against isp-1(−)/control RNAi worms in the same experimental sets. “Figures in text” indicates lifespan dataset that was used in indicated figures.

Data Availability Statement

The published article includes all data generated in this study.