Abstract

Plasminogen-binding group A streptococcal M-protein (PAM) is a signature surface virulence factor of specific strains of Group A Streptococcus pyogenes (GAS) and is an important tight binding protein for human plasminogen (hPg). After activation of PAM-bound hPg to the protease, plasmin (hPm), GAS cells develop invasive surfaces that are critical for their pathogenicity. PAMs are helical dimers in solution, which are sensitive to temperature changes over a physiological temperature range. We previously categorized PAMs into three classes (I–III) based on the number and nature of short tandem α-helical repeats (a1 and a2) in their NH2-terminal A-domains that dictate interactions with hPg/hPm. Class II PAMs are special cases since they only contain the a2-repeat, while Class I and Class III PAMs encompass complete a1a2-repeats. All dimeric PAMs tightly associate with hPg, regardless of their categories, but monomeric Class II PAMs bind to hPg much weaker than their Class I and Class III monomeric counterparts. Additionally, since the A-domains of Class II PAMs comprise different residues from other PAMs, the issue emerges as to whether Class II PAMs utilize different amino acid side chains for interactions with hPg. Herein, through NMR-refined structural analyses, we elucidate the atomic-level hPg-binding mechanisms adopted by two representative Class II PAMs. Furthermore, we develop an evolutionary model that explains from unique structural perspectives why PAMs develop variable A-domains with regard to hPg-binding affinity.

Introduction

Group A Streptococcus pyogenes (GAS) is a Gram-positive β-hemolytic pathogen, the natural host of which is humans. This microorganism causes a range of diseases, from mild and treatable pharyngitis and impetigo to life-threatening invasive pathologies, such as necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome [1,2]. Globally, ~700 M humans are infected with GAS each year. More than 18 M of these cases become severe and ~1 M progress to the invasive stage, resulting in ~550 000 deaths/year [3].

M-proteins are multi-copy surface virulence factors in all GAS strains and are encoded by the emm gene. Mature M-proteins are covalently bound to the cell wall and extend beyond the GAS surface into the extracellular environment as hair-like projections [4,5]. GAS strains are commonly classified via the 5′-hypervariable end of the emm gene (emm typing) [6,7], and >250 emm types of GAS have been classified by this approach. In addition to the emm gene, four other genes, namely, enn, fcr, scpa, and fbpa, are secluded in a small virulence region of GAS, termed the multiple gene activator (Mga) regulon. Mga is a stand-alone regulator of the transcription of these genes that are employed by GAS for adherence, internalization, and evasion of the host innate immune response to GAS infection. The presence and order of the Mga regulon genes are further used to subtype GAS, as Patterns A–E [8]. Such characterizations of GAS are very useful for epidemiology, tissue tropicity, and potential virulence of GAS outbreaks.

Our interest is focused on the numerous skin-tropic Pattern D strains, which contain all of the mga regulon genes. In Pattern D strains, the signature M-protein (referred to as plasminogen-associated M-protein; PAM) [9]), directly binds to the lysine-binding site (LBS) in the kringle 2 domain of human plasminogen (hPg) (K2hPg) [10] through its 30-residue A-domain located near the NH2-terminus of PAM [11]. The A-domain of PAM-type M-proteins contains hPg binding sites in one or two helical tandem repeats, viz., a1 and a2 [11–13], and Arg–His residues within the a1- and/or a2-repeats (RH1 and RH2, respectively) are necessary for hPg binding [14,15]. The protease, human plasmin (hPm), generated from activation of hPg by GAS-secreted streptokinase (SK), then catalyzes the degradation of the protective fibrin that is initially formed to encapsulate GAS cells [16].

We previously categorized PAMs into three classes, based on the amino acid sequences of their A-domains [17,18]. Class I PAMs refer to those expressing two tandem hPg-binding a-repeats, e.g. a1a2, in the A-domain, as is the PAM present in a widely investigated invasive isolate AP53 (PAMAP53). Class II PAMs, expressed from certain isolates, e.g. NS88.2 and SS1448 (PAMNS88.2 and PAMSS1448), lack the a1-repeat. Class III PAMs express intact a1a2-repeats as their Class I counterparts but also contain a VHD or DHD tripeptide inserted at the COOH-termini of their a1-repeats. All of these PAMs tightly associate with hPg with a low nM-range Kd at 25° C [17]. Thus, the question arises as to why two a-repeats are present in the A-domain of some GAS strains. We previously found that, at 37°C, the hPg-binding affinities of Class II PAMs are reduced ~1000-fold, while PAMs from the other two classes still interact with hPg with only a slightly weaker affinity at this higher temperature [18]. Thus, Class II PAMs with only one a-repeat are special cases in terms of hPg binding. Since the only known functional role for the a1a2 helical repeats is to interact with hPg/hPm, we probed the question as to whether two a-repeats provide a more stable helical hPg-binding locus. In addition to this impact of A-domain secondary structure on the hPg binding affinity, the amino acid composition of the A-domain is another potential hPg binding determinant, possibly providing exosites for tight binding. To examine these questions using modeled structures, we constructed two A-domain-containing peptides from Class II PAMs, i.e. A95GL55NS88.2 and K85TI55SS1448. They both have been proven to be monomers at 25°C [17] and to interact with hPg >1000-fold weaker than V97EK75AP53, a peptide truncated from PAMAP53 (Class I) that contains both a1- and a2-repeats [18].

Several structures of K2hPg complexed with different Class I PAMAP53-derived peptides have been published [13,19–21]. Herein, we applied high-resolution NMR for the modeling of two other complex structures, AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg and KTI55SS1448/K2hPg, to reveal the atomic-level hPg-binding mechanisms of Class II PAMs. It is relevant to investigate how PAM in its monomeric state binds to hPg, since a considerable fraction of PAM exists as monomers at physiological temperature. In addition, we discovered that the hPg-binding affinity constitutes a driving force in the evolution of the A-domain structure.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

M-protein sequences referred to on this work were from GAS strains AP53 (emm53) [22]; NS88.2 (emm98.1) and SS1448 (emm86.2) [23]; GLS250 (emm56), GLS263 (emm72), GLS307 (emm 116), and GLS312 (emm121) [24]; and SF370 (emm1) [25].

Expression and purification of K2hPg, AGL55NS88.2, and KTI55SS1448

The amino acid sequences of all peptides used in this work are listed in Table 1. The amino acid residue numbering system for the PAM-derived peptides is based on the full-length parent proteins, i.e. PAMNS88.2 for A95GL55NS88.2 and PAMSS1448 for K85TI55SS1448, with the first residue of the parent PAM as M1 of the signal peptide, as has been the convention in most previous studies (Figure 1, Table 1).

Table 1.

Sequences of K2hPg and PAM-derived peptides

| Peptide | Amino acid sequencea |

|---|---|

| K2hPg | [YVEFSEE]C166MHGS170GENYD175GKISK180TMSGL185ECQAW190DSQSP195HAHGY200IPSKF205PNKNL210KKNYC215RNPDR220 DLRPW225CFTTD230PNKRW235EYCDI240PRC243[AA] |

| AGL55NS88.2 | [GS]A95GLQEK100ERELE105DLKDA110ELKRL115NEERH120DHDKR125EAERK130ALEDK135LADKQ140EHLDG145ALRY149 |

| KTI55SS1448 | [GS]K85TIQEK90EQELK95NLKDN100VELER105LKNER110HDHDE115EAERK120ALEDK125LADKQ130EHLDG135ALRY139 |

| VKK38NS455 | [GS]V103KK105LNDEV110ALERL115KNERH120VHDEE125VELER130LKNER135HDHD139[Y] |

| VEK75AP53 | [GS]E88EL90QGLKD95DVEKL100TADAE105LQRLK110NER113H114E115EAELE120RLKSE125R126H127DHD130KKEAE135RKALE140 DKLAD145KQEHL150NGALR155YINEK160EA162 |

Residues within the brackets are exogenous, originating from the plasmids. Superscript numbers are designated as the position of each residue in the corresponding full-length parent protein. The PAM-binding-relevant residues in K2hPg are labeled in bold, while the RH-motifs in all the PAM-derived peptides are also emphasized in bold.

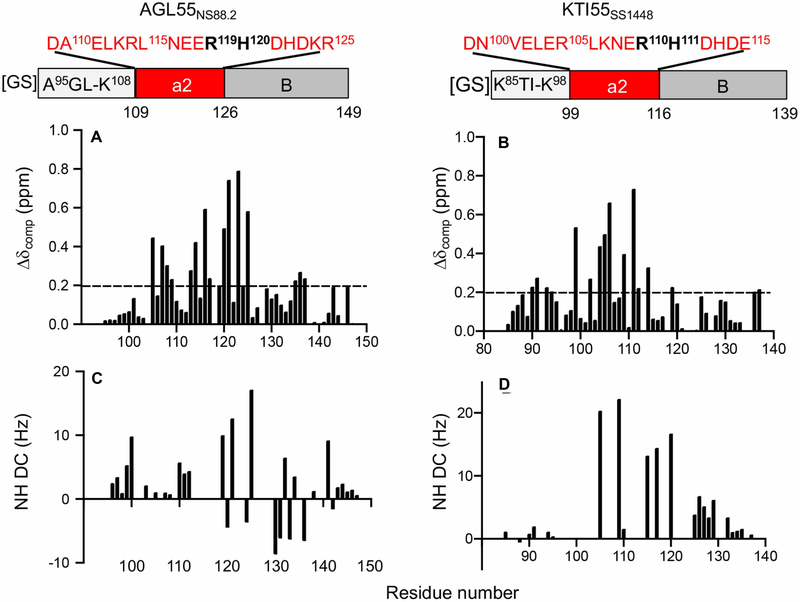

Figure 1. Correlation of peptide sequences, chemical shift changes, and RDC restraints.

Residue-specific chemical shift changes in [13C,15N]-AGL55NS88.2 and [13C,15N]-KTI55SS1448, before and after binding to unlabeled K2hPg. (A) AGL55NS88.2 peptide includes a partial hypervariable region (residues 95–108), an A-domain (a2-repeat, residues 109–125), and a partial B-domain (residues 126–149). (B) KTI55SS1448 peptide includes a partial hypervariable region (residues 85–98), an A-domain (a2-repeat, residues 99–115), and a partial B-domain (residues 116–139). Both PAM-derived peptides contain 57 residues in total. The exogenous G−2S−1 dipeptides at the NH2-termini are not counted in the numbering of the peptide linear sequences. The numbers refer to the position of each residue in the corresponding full-length PAM. The a2-repeat sequence in each peptide is shown in red, and the RH-motif is labeled in black. (C, D) The RDC restraints of unlabeled K2hPg-bound [13C,15N]-AGL55NS88.2 and unlabeled K2hPg-bound [13C,15N]-KTI55SS1448, respectively.

Pichia pastoris-expressed K2hPg, consisting of residues C166-C243 of mature hPg (minus the 19 amino acid signal peptide) has been described previously along with its expression and purification methodology [26]. The K2hPg used in this work contains three substitutions of C169G/E221D/L237Y, to enhance its binding affinity to PAM-derived peptides without altering the specificity of binding [27]. Unlabeled and fully labeled [13C,15N]-K2hPg were expressed and purified as previously reported [27,28].

Plasmids for expression of the PAM-derived peptides were prepared as previously described [13,29]. AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 were cloned from PAMNS88.2 and PAMSS1448, respectively [17]. These plasmids were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells employing the His6-tagged-GB1 domain fusion expression system [29]. [13C, 15N]-PAM-derived peptides were similarly expressed as other isotope-labeled peptides that have been reported [13,18,21,28,29].

NMR data collection of the bound forms of [13C,15N]-labeled peptides

All NMR spectra were collected at 25° C on a Bruker AVANCE 800 spectrometer with a 5 mm triple resonance (TCI, 1H, 13C, 15N) cryoprobe. The [13C,15N]-labeled peptides were dissolved in 20 mM BisTris-d19 (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories), 5% 2H2O in H2O/20 μM 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS)/0.1% NaN3, pH 6.7. The concentration of isotope-labeled peptides was ~1 mM, which generated a high signal-to-noise ratio in the NMR spectra. DSS served as a calibration standard for 1H chemical shifts, and 13C and 15N chemical shifts were indirectly referenced to DSS [30].

Due to the large sizes of the AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg and KTI55SS1448/K2hPg complexes, experiments for resonance assignments were carried out in the transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy (TROSY) mode to enhance sensitivity, including TROSY-[15N]-HSQC, TROSY-HNCO, TROSY-HN(CA)CO, TROSY-HNCACB, TROSY-(H)CC(CO)NH, TROSY-H(CC)(CO)NH, and TROSY-HBHA(CBCA)NH [31,32]. Prior to these TROSY experiments, a series of titrations were conducted, in which the molar ratios of [13C,15N]-AGL55NS88.2 or [13C,15N]-KTI55SS1448 and unlabeled K2hPg were 1:0, 1:0.25, 1:0.5, 1:0.75, 1:1, and 1:1.25, to ensure that AGL55NS88.2 or KTI55SS1448 were saturated with K2hPg. Then, TROSY-[15N]-HSQC spectra were collected. The HSQC spectra did not change beyond a molar ratio of 1:1.

Subsequent to these titrations, [15N]-HSQC spectra were also recorded for comparisons with those of the apo-forms of [13C,15N]-AGL55NS88.2 and [13C,15N]-KTI55SS1448.

Intra- and inter-molecular NOE distance restraints

To analyze intramolecular NOE distance restraints of AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 in the corresponding complexes, TROSY-[15N]-NOESY-HSQC and [13C]-HSQC-NOESY-[15N]-HSQC spectra were collected [33]. Intermolecular NOE distance restraints were determined using complexes of unlabeled AGL55NS88.2/[13C,15N]-K2hPg and unlabeled KTI55SS1448/[13C,15N]-K2hPg. The 2D NOESY spectra, with filtration of 13C and 15N, were collected with a 120 ms mixing time. The [13C,15N]-filtered/edited 3D NOESY-[1H,15N]-HSQC spectra were recorded under the same conditions [34]. Given that both unlabeled K2hPg-bound [13C,15N]-AGL55NS88.2 and K2hPg-bound [13C,15N]-KTI55SS1448 displayed some overlapping peaks, thus causing uncertainties for the assignments of cross-peaks in the NOESY spectra, intermolecular NOEs collected from these two samples were not included as distance restraints in the docking.

Residual dipolar coupling

Residual dipolar coupling (RDC) data were also collected for each peptide/K2hPg complex, [13C,15N]-AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg, [13C,15N]-KTI55SS1448/K2hPg, unlabeled AGL55NS88.2/[13C,15N]-K2hPg, and unlabeled KTI55SS1448/[13C,15N]-K2hPg, by adding bacteriophage pf1 to a final concentration of 10 mg/ml. Measurements of 1DNH RDCs were conducted by IPAP[1H,15N,]HSQC experiments [35]. For each residue, the RDC values were calculated from the difference in the corresponding spin–spin splitting, i.e. J-coupling, determined in isotropic H2O and in the liquid crystal state driven by pf1.

Chemical shift perturbations

On the basis of [1H,15N]-HSQC spectra, chemical shift perturbation (CSP) values were calculated for each residue of [13C,15N]-AGL55NS88.2 and [13C,15N]-KTI55SS1448. The underlying equation for these calculations is: ΔδHN,N = [(ΔδHN)2 + (ΔδN/6)2]1/2, wherein ΔδHN,N represents the overall CSP with respect to the amide hydrogen and nitrogen, and ΔδHN and ΔδN refer to the chemical shift changes of 1H and 15N in the backbone, respectively, between the apo- and unlabeled K2hPg-bound forms [36]. The CSPs were determined in the same manner for [13C,15N]-K2hPg between the apo- and unlabeled AGL55NS88.2/[13C,15N]-K2hPg (or between apoand unlabeled KTI55SS1448/[13C,15N]-K2hPg forms).

Modeling of solution structures by NMR

Dihedral angle restraints determined by TALOS-N [37], intramolecular distance restraints, and assigned chemical shifts of the backbone and side chains were used in the structure calculations of AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 in their complexes with K2hPg, through a simulated annealing protocol in Xplor-NIH 2.42 [38–40]. This process generated 200 structures in each simulation, the quality of which were evaluated by MolProbity [41,42]. One of the lowest-energy structures of each peptide that exhibited the best geometries were used in the subsequent docking. PyMOL was applied to visualize calculated structures.

High ambiguity-driven protein–protein docking

The structures of AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg and KTI55SS1448/K2hPg were calculated through the high ambiguity-driven protein–protein docking (HADDOCK) platform on the basis of multiple restraints [43]. In each complex, the residue numbers in the linear sequence of K2hPg, AGL55NS88.2, and KTI55SS1448 are designated as 166–243, 95–149, and 85–139, respectively (Table 1). Two short terminal fragments in recombinant K2hPg, i.e. the exogenous residues in Y−7VEFSEE−1 and the A1001A1002, are not derived from the linear sequence of K2hPg, but from the cloning steps. Likewise, the NH2-terminal G−2S−1 dipeptide in both AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 originates from the expression plasmid after the cleavage by thrombin. All of these exogenous sequences are not counted in the numbering of the corresponding peptide.

The structure of K2hPg applied here is derived from the complex structure of VEK75AP53/K2hPg [20]. Three fragments consisting of residues 198–210, 218–226, and 233–236 in K2hPg, which contribute to the interactions with the A-domain of PAMs, were set as semi-flexible. The terminal residues, Y−7VEFSEE−1 and A1001A1002, are defined as fully flexible.

The NMR-refined structures of AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 in the complexes were calculated using the Xplor-NIH 2.42 program. Residues in the α-helices were designated as semi-flexible, including the binding-relevant RH-motif, whereas the mobile loops in the A-domain or the termini were considered fully flexible. Specifically, for AGL55NS88.2, the semi-flexible regions consisted of residues 99–101, 108–114, and 118–135. The fully flexible segments covered residues −2, −1, 95–98, 102–107, 115–117, and 136–149. In the case of KTI55SS1448, residues 98–103 and 109–115 were designated as semi-flexible; residues −2, −1, 85–97, 104–108, and 123–139 were chosen as fully flexible segments (Table 1).

The intramolecular NOE distance restraints of [13C,15N]-AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg or [13C,15N]-KTI55SS1448/K2hPg, along with the corresponding intermolecular distance restraints, were used as unambiguous restraints for each complex, wherein 10% of the total NOE restraints were randomly excluded. The dihedral angle restraints of AGL55NS88.2 or KTI55SS1448 in the complexes with K2hPg were also employed to refine their overall secondary structures during the docking. One-half of the randomly selected RDC restraints were applied to both K2hPg and AGL55NS88.2, or KTI55SS1448. Complex structures generated from HADDOCK were finally evaluated by the total RDC restraints. For the complex of AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg, the rhombicity (Rh) and axiality (Da) with respect to the alignment tensor were initially set as 0.330 and 22.23, respectively, which were determined in the program Xplor-NIH 2.42. Likewise, for the complex of KTI55SS1448/K2hPg, Rh and Da were set as 0.138 and 21.30, respectively. Solvated docking was performed, and water was chosen as the solvent for the last iteration. Energy constants for unambiguous restraints at each stage were set as follows: hot, 1.0; cool-1, 1.0; cool-2, 5.0; cool-3, 5.0. A total of 200 refined structures were generated in each simulation [44].

Representative structures in the cluster holding the largest population that presented the lowest energy, the smallest RMSD, and accordingly, the most negative HADDOCK score were selected [43]. These structures were examined through MolProbity in terms of all-atom contacts and protein geometry [41,42]. For each complex, 20 of the best structures were overlaid on the K2hPg moiety for the subsequent deposition. Detailed statistics with respect to structural calculations are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Surface plasmon resonance

Binding kinetics of recombinant PAM-derived peptides to K2hPg were measured in real time in a BIAcore X100 Biosensor System (GE Healthcare). The running buffer, HBS-EP (10 mM Hepes/150 mM NaCl/3 mM EDTA/0.005% polysorbate 20, pH 7.4), was used at a flow rate of 30 μl/min. K2hPg, diluted to 30 μg/ml in 10 mM NaOAc, pH 4.5, was injected to a level of 1000 RUs into flow cell-2 of CM5 sensor chip for the amine-coupling immobilization. Flow cell-1 was prepared in the same way, but no ligands were injected and absorbed onto the chip in this reference cell. Ethanolamine (1 M, pH 8.5), was subsequently injected to deactivate excessive succinimide esters on the gold surface of the sensor chip.

To determine KD values, the analyte, dissolved in the HBS-EP buffer at various concentrations, was injected for an association time of 120 s and a dissociation time of 360 s onto a K2hPg-coupled CM5 chip. In each cycle, after the dissociation stage, the gold surface was regenerated using 10 mM glycine, pH 2.0. Binding data collected in flow cell-2 were subtracted from those obtained in flow cell-1, in which no ligands were bound. Using the BIA evaluation software (Version 2.0.1; GE Healthcare), the KD values were calculated from the ratio of the dissociation (koff) and association rate constants (kon). A nonlinear fitting binding model with a 1:1 stoichiometry was employed to the entire binding curve. The results were plotted in GraphPad Prism 6.0.

Construction of SK-β domain phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree was constructed to show the classification of SKs among 28 GAS strains using their 423 bp β-domain-encoding sequences (corresponding to amino acids 147–287 in each SK). The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method [45] using MEGA7 [46] (scale bar = 0.05 substitutions per site). The GenBank accession numbers for each SK-β domain are listed below: 5448 (EU352628.1), ALAB49 (AY234294.1), AP53 (JX898183.1), D964 (AY234281.1), JRS4 (CP011414.1), M23ND (CP008695.1), Manfredo (AY234141.1), MGAS315 (AE014074.1), MGAS8232 (AE009949.1), NS10 (EU352637.1), NS13 (EU352638.1), NS32 (EU352630.1), NS50.1 (EU352632.1), NS53 (EU352641.1), NS59 (EU352640.1), NS88.2 (JX898186.1), NS210 (EU352612.1), NS223 (JX898184.1), NS253 (EU352636.1), NS455 (JX898185.1), NS696 (EU352629.1), NS931 (EU352623.1), NS1133 (EU352633.1), NZ131 (M19347.1), SF370 (AE004092.2), SS1572 (AY234263.1), SS1574 (AY234270.1). The nucleotide sequence of SK-β domain from SS1448 is identical with that from D964. The alignment of SK-β domain amino acid sequences is shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Results

Chemical shift changes in the [1H,15N]-HSQC spectra indicate the active binding region

A significant CSP reflects a change in the chemical environment surrounding the corresponding residue, which is mainly determined by variations in the secondary structures and/or associations with binding partners. We thus calculated CSP values to reveal amino acid side chains of PAM-derived peptides that were most affected by their interactions with K2hPg.

In the case of AGL55NS88.2 (Table 1, Supplementary Figure S2), most of the large CSPs, with ΔδHN,N values >0.2, are correlated with residues in the a2-repeat, including D109, K113, R114, N116, E117, R119, H120, D121, D123, K124, and R125 (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure S3). Three residues at the COOH-terminal end of the upstream hypervariable region (HVR) of PAMNS88.2, specifically, E105, L107, and K108, also demonstrate relatively large CSPs (Figure 1A). Considering that the a-repeat is responsible for binding to K2hPg, it is expected that residues in this binding region are influenced most when they interact with K2hPg.

A similar phenomenon was observed in the correlation between the KTI55SS1448 sequence (Table 1, Supplementary Figure S2) and the CSP of each residue. The residues in the single a-repeat, namely, D99, E102, E104, R105, L106, E109, H111, D112, and D114, along with several residues in the HVR, including K90, E91, E93, and L94, exhibit CSP values > 0.2 (Figure 1B, Supplementary Figure S4). Notably, R110 in the RH-motif of KTI55SS1448 displays almost identical 1H and 15N chemical shifts with or without binding to K2hPg, indicating that R110 may be less involved in the interaction with K2hPg than H111, a residue that shows the largest CSP among all the residues in KTI55SS1448.

With respect to K2hPg, before and after binding to AGL55NS88.2 or KTI55SS1448, the amide proton and nitrogen atoms of most residues show similar chemical shifts. Only residues E172, I201, S203, K208, K211, L222, and W225 present CSP values >0.2 when K2hPg binds to AGL55NS88.2 (Supplementary Figure S5A). This is also the case for E172, S183, G199, I201, S203, K208, K211, D221, and W225 of K2hPg, when this domain binds to KTI55SS1448 (Supplementary Figure S5B). However, of these residues, only K208, D221, and W225 of K2hPg have been substantiated in other studies to be important in its binding to PAM-derived peptides [13,20,21]. G199 and I201 are the two residues flanking Y200, the hydroxyl oxygen of which is involved in a hydrogen bond with Hε of Arg in the RH-motif [13,20,21]. On the basis of these chemical shift changes, LBS residues 218–226 and 233–236, as well as a segment covering Y200 and K208 (residues 198–210) in K2hPg, are selected to be flexible in the protein docking.

RDC values reveal a specific orientation of the A-domain of PAM-derived peptide in the K2hPg-binding complex

It is noteworthy to find that, for AGL55NS88.2 or KTI55SS1448 complexed with K2hPg, residues in the A-domain, as well as a portion of the downstream B-domain, display large RDC values. These large RDCs indicate that the abovementioned regions are oriented in a specific manner in the complex. Specifically, R119, D121, and R125 show the largest RDC values among all residues in K2hPg-bound AGL55NS88.2 (Figure 1C), while R105, E109, E115, A117, and K120 in KTI55SS1448 show significant amide-nitrogen RDCs (>10 Hz) upon binding to K2hPg (Figure 1D).

The secondary structures of AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 are altered upon binding to K2hPg

Based on the chemical shift assignments for each peptide, we next applied TALOS-N [37] to calculate dihedral angles and to predict the secondary structures of each peptide. The results show a lower probability of α-helix in the RH-motif of apo-AGL55NS88.2 (R119H120; Figure 2A) and apo-KTI55SS1448 (R110H111; Figure 2B) than in the residues flanking this motif. These findings support the previously reported mobile feature of this motif in the absence of binding to K2hPg [17]. Notably, a long fragment within KTI55SS1448, K107NERHDHD114, is not α-helical (Figure 2B), consistent with the calculated solution structure [17].

Figure 2. The secondary structures of AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 significantly vary with or without binding to K2hPg.

The probability of an α-helix for each residue was predicted using the TALOS-N program. (A) apo-AGL55NS88.2; (B) apo-KTI55SS1448; (C) K2hPg-bound AGL55NS88.2; (D) K2hPg-bound KTI55SS1448. (E) The solution structures of apo- (white) and K2hPg-bound AGL55NS88.2 (green) that are overlaid in the range of residues 123–133 (RMSD = 0.117). The loop consisting of L115N116E117 is shown in red. (F) The solution structures of apo- (white) and K2hPg-bound KTI55SS1448 (green) that are overlaid in the range of residues 116–121 (RMSD = 0.039). (E, F) The RH-motifs are displayed as sticks. The apo-form solution structures of AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 have been published [17], and are shown here for comparison with the K2hPg-bound peptide structure.

When each PAM-derived peptide binds to K2hPg, residues that are involved in a helical structure or a flexible loop are rearranged. In K2hPg-bound AGL55NS88.2, the segment consisting of L115N116E117 displays a lower probability of an α-helix than this peptide in the absence of K2hPg (Figure 2C). In the case of KTI55SS1448, helical segments move towards the RH-motif once this peptide interacts with K2hPg (Figure 2D). The solution structure of AGL55NS88.2 in complex with K2hPg confirms the existence of the short loop, L115N116E117, upstream of the RH-motif (Figure 2E). For both AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448, K2hPg-binding alters the conformation of the RH-motif to a more helical orientation (Figure 2E,F). Nevertheless, mobile features still dominate the overall structure of KTI55SS1448 in the complex, exhibiting two loops, E104RLKN108 and D112H113D114, surrounding the R110H111-motif (Figure 2F).

AGL55NS88.2 utilizes multiple sites in the A-domain to bind to K2hPg

A total of 13 and 9 intermolecular NOEs were observed for AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg and KTI55SS1448/K2hPg complexes, respectively (Table 2). In the case of AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg, side-chain intermolecular NOEs predominately occur between residues E111 of AGL55NS88.2 and R220 of K2hPg, and between R119 of AGL55NS88.2 and W225/W235 of K2hPg. It is known from structural and mutagenesis studies that W225 and W235 form the hydrophobic region of the K2hPg LBS [12,27,47–51]. Similarly, for the complex of KTI55SS1448/K2hPg, the sequence H111DH in KTI55SS1448 is in proximity to W225/W235 of K2hPg.

Table 2.

Intermolecular NOE in the complexes of AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg and KTI55SS1448/K2hPg

| AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg |

KTI55SS1448/K2hPg |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| K2hPg | AGL55NS88.2 | K2hPg | KTI55SS1448 |

| Y200-Hη | R119-Hε | R220-HN | V101-Hγ |

| R220-HN | E111-Hβ | D221-HN | N108-Hδ |

| R220-Hγ | E111-Hγ | W225-HN | H111-Hε1 |

| R220-Hε | E111-Hβ | W225-Hε1 | H111-Hδ2 |

| R220-Hη | E111-Hβ | W225-Hε1 | H111-Hε1 |

| R220-Hη | E111-Hγ | W235-Hε1 | H113-HN |

| W225-Hε1 | R119-Hε | W235-Hε1 | D112-Hβ |

| W225-Hε1 | R119-Hη | W235-Hδ1 | H111-Hα |

| R234-HN | E126-Hβ | W235-Hζ2 | D112-Hα |

| W235-Hε1 | R119-Hγ | ||

| W235-Hε1 | R119-Hδ | ||

| W235-Hε1 | R119-Hη | ||

| W235-Hε1 | H122-Hβ | ||

We next applied the HADDOCK program to conduct modeling of complex structures, mainly based on the intermolecular NOE and RDC restraints. We further used both HADDOCK scores and RDC restraints to evaluate the quality of the calculated complex structures (Supplementary Figure S6). Given that a loop consisting of L115N116E117 disrupts the α-helix in the A-domain, the overall structure of AGL55NS88.2 in complex with K2hPg appears in a ‘V’-shape (Figure 3A). Three sets of interactions were found between AGL55NS88.2 and K2hPg, among which two are related to the D219R220D221-motif in the LBS of K2hPg. First, the anionic carboxyl group of E111 in AGL55NS88.2 inserts into the cationic center formed by K208 and R220 in K2hPg, with a distance of 1.8 Å to either positively charged head, allowing the formation of hydrogen bonds in addition to electrostatic attractions (Figure 3B). However, partially attributable to movement of the long side chains of K208 and R220 in K2hPg, this proximity is variable in different low energy complex structures, even rising to ~4.0 Å, which disfavors the formation of an H-bond between E111 in AGL55NS88.2 and K208 of K2hPg as illustrated in another low energy structure (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. The K2hPg-binding mechanism of AGL55NS88.2.

The backbones of K2hPg and AGL55NS88.2 are shown in green. The relevant binding residues in K2hPg are shown in light purple, and in orange for those in AGL55NS88.2. (A) A total of 20 modeled complex lowest energy structures that are overlaid on the K2hPg moiety (residue 166–243), with an averaged RMSD of 0.244. (B, D–F) Derived from the same low energy complex structure with the fewest violations. The interactions shown in (C, G) are from a different calculated low energy complex structure to illustrate the variable proximity among corresponding residues in these two binding sites. A dashed line represents a hydrogen bond, with the corresponding distance labeled (in Å). Residues are displayed as sticks when necessary for the analysis of interactions.

The second interaction occurs at the LBS of K2hPg. Specifically, the guanidinium cation of R119 in AGL55NS88.2 electrostatically attracts the anionic side chains of D219 and D221 in K2hPg. Meanwhile, the -NH2 side chain of N116 in AGL55NS88.2, together with R119, initiates a network of hydrogen bonds (1.8–2.5 Å) with D219 and D221 in the LBS (Figure 3D). In some low energy structures, the Hε of R119 mediates a hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl group of Y200 in K2hPg, but this is dependent on the orientation of R119 in the binding pocket. Moreover, the indole groups of W225 and W235 in K2hPg provide a hydrophobic niche that accommodates the aliphatic side chain of R119. This hydrophobic clustering expels H2O molecules, thereby making the insertion of R119 into the LBS more energetically favorable. This also reinforces the concept that both electrostatic attractions and hydrogen bonds are favorable between R119 of AGL55NS88.2 and D219/D221 of K2hPg (Figure 3D).

It was previously reported that the side chain of R234 in K2hPg interacts with the negatively charged side chains of E112 and E116 in the various VEK-peptides from PAMAP53, through electrostatic attractions and/or hydrogen bonds [13,20]. But such interactions disappear in the case of AGL55NS88.2, which is ascribed to the DHD tripeptide following the RH-motif (Figure 3E). Unlike PAMAP53 (Class I) that features an E112RHEE (Table 1, Supplementary Figure S2) sequence at the end of the a1-repeat, PAMNS88.2 is naturally devoid of the a1-repeat, and thus only contains the a2-repeat that interacts with hPg. Therefore, this sequence, E112RHEE, is absent from PAMNS88.2 and its derived peptide, AGL55NS88.2. On the other hand, the other highly conserved sequence, ERHDHD, which exists in the a2-repeat of different PAMs, is also present in AGL55NS88.2. As a consequence, by means of steric hindrance, the imidazole ring of H122 in this DHD tripeptide maintains the cationic side chain of R234 in K2hPg distal from the anionic E118 and D121 in AGL55NS88.2 (Figure 3E). Therefore, the positively charged head group of R234 in K2hPg is not involved in the interaction with AGL55NS88.2.

A third interaction was found outside the LBS of K2hPg. The negatively charged carboxyl group of E126 in AGL55NS88.2 is in proximity (1.8–2.0 Å) to the cationic amine group of K233 and the amide proton (HN) of R234 in K2hPg (Figure 3F). But the interaction between E126 and K233 is unstable because the side chains of these two residues can be separated as much as 4.0 Å in some low energy structures (Figure 3G). In contrast, since an intermolecular NOE cross-peak was observed for Hβ of E126 and HN of R234 (Table 2), this proximity ensures a stable hydrogen bond between the two residues. Furthermore, D123 in AGL55NS88.2 may present a weak electrostatic attraction with K233 in K2hPg, with a distance of ~4.0 Å between their charged heads (Figure 3F–G). In a previously reported structure of another complex, VKK38NS455/K2hPg, a hydrogen bond between D123 in VKK38NS455 and K233 in K2hPg was observed [28], indicating that the latter Asp residue in the RHDHD (or RHVHD) sequence is universally involved in the interaction with K2hPg, albeit to different extents.

The distance between the RH-motif and the LBS of K2hPg dictates the binding affinity

It has been shown that the hPg-binding of AGL55NS88.2 is >1000 times weaker than that of VEK75AP53 [18], mainly due to the rapid dissociation rate of the AGL55NS88.2/hPg complex. Likewise, AGL55NS88.2 binds to K2hPg with a ~300-fold lower affinity than VEK75AP53 (Figure 4A and B; Table 3). Thus, the reasons that AGL55NS88.2 displays a high dissociation rate in the surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based measurements of its K2hPg or hPg binding affinity need to be assessed. When the K2hPg moieties from K2hPg/AGL55NS88.2 and K2hPg/VEK75AP53 complexes are overlaid, it can be seen that the RH-motif in AGL55NS88.2 is ~2.5 Å farther from the active site of K2hPg than the counterpart residues in VEK75AP53 (Figure 5A). This suggests that the RH-motif in AGL55NS88.2 would readily dissociate, thus accounting for the high off-rate found in the K2hPg-binding assays (Figure 4B). The loop of L115NE determines this longer distance of the RH-motif in AGL55NS88.2 from the binding site of K2hPg. When the two complex structures are superimposed on the consensus sequence ERHDHD in the PAM-derived peptides, the helix preceding the L115NE loop in AGL55NS88.2 clashes with the K2hPg moiety from the K2hPg/VEK75AP53 complex (Figure 5B). L104 and E111 in AGL55NS88.2 would thus conflict with K208 and R220 in K2hPg, respectively, if the RH-motif in AGL55NS88.2 were as close to the binding locus in K2hPg as that in VEK75AP53.

Figure 4. SPR binding assays of PAM-derived peptides to K2hPg at 25°C.

The concentrations of peptides are as indicated in each panel. Kinetic analyses were performed for (A) VEK75AP53, (B) AGL55NS88.2, and (C) KTI55SS1448. The experimental data are shown in black lines and best-fit curves are shown in red lines. The experimental data were fit using a 1:1 (m:m) Langmuir binding model.

Table 3.

Binding kinetics of PAM-derived peptides to K2hPg at 25°C

| Peptides | kon (×106 Ms−1) | koff (×10−4 s−1) | KD (kinetics)a (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGL55NS88.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 840 ± 24 | 59 ± 5 |

| KTI55SS1448 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 1540 ± 150 | 46 ± 2 |

| VEK75AP53 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.01 |

KD values were calculated from koff/kon. Data were collected from triplicate runs, and presented as the mean ± SD.

Figure 5. The atomic-level mechanism underlying the weaker binding of AGL55NS88.2 to K2hPg, compared with VEK75AP53.

The structure of the complex of VEK75AP53/K2hPg is displayed in white, while the complex of AGL55NS88.2/K2hPg is shown in green. The RH-motif and N116 in AGL55NS88.2 are highlighted in orange, and are shown as sticks. The dashed lines or circles represent geometric clashes generated in the corresponding overlaid structures. (A) The two complex structures are overlaid on the K2hPg moiety; (B, C) the two structures are overlaid on the consensus sequence, ERHDHD, in the a2-repeat of PAM-derived peptides.

An additional consideration is the interference of N116 in K2hPg binding. This residue would insert into the LBS in K2hPg, and correspondingly expel R119 in AGL55NS88.2 towards the edge of LBS. As a result, a clash between W235 in K2hPg and R119 would occur (Figure 5C). On the basis of these geometric clashes, it is unrealistic for the RH-motif in AGL55NS88.2 to move closer to the LBS in K2hPg. The side chain of H120 in AGL55NS88.2 thus fails to remain in proximity to the carboxyl group of D221 of K2hPg, which otherwise leads to a hydrogen bond, as illustrated in the complex structure of K2hPg/VEK75AP53. This loss-of-function at the H120 supplements the explanation of the non-ideal binding mode of AGL55NS88.2 to K2hPg.

Overall, the flexible region in the A-domain of AGL55NS88.2, albeit short, renders its binding to K2hPg significantly weaker than VEK75AP53.

H111 of the RH-motif in KTI55SS1448 substantially contributes to K2hPg binding

Similar to the K2hPg binding of AGL55NS88.2, multiple residues in KTI55SS1448, which also only contains the a2-repeat, are critical to its interaction with K2hPg, even though this peptide exhibits a more flexible overall structure (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. The K2hPg-binding mechanism of KTI55SS1448.

The backbones of both K2hPg and KTI55SS1448 are shown in green. The relevant binding residues in K2hPg are shown in light purple, and in orange for those in KTI55SS1448. (A) A total of 20 modeled complex structures that are overlaid on the K2hPg moiety (residue 166–243), with an averaged RMSD of 0.230. (B, D, and F) Derived from the same low energy complex structure with the fewest violations. The interactions shown in (E,G) are from a different low energy complex structure to illustrate the variable proximity among corresponding residues in the two binding sites. (C) Displays an insertion of neutral H111 (Hε tautomer) into the LBS of K2hPg. A dashed line represents a hydrogen bond, with the corresponding distance labeled (in Å). Residues are displayed as sticks when necessary for the analysis of interactions.

The most significant interaction between KTI55SS1448 and K2hPg involves the role of H111 in the stability of binding. The structures of KTI55SS1448/K2hPg with the lowest energy show an insertion of H111, rather than R110, of KTI55SS1448, into the LBS of K2hPg (Figure 6B). The imidazole side chain of H111, either protonated or neutral (Figure 6C), clusters with the hydrophobic indole rings of W225 and W235 in K2hPg, providing a C–C distance <4.0 Å. A positive charge renders H111 electrophilic, and facilitates entry of this residue into an electronegative niche induced by the delocalized π-bonds of W225 and W235 in K2hPg. Also, Hδ1 of H111 mediates hydrogen bonding with D221 in the LBS of K2hPg, and the side chain NH2 of N108 is in proximity (1.8 Å) to the carboxyl oxygen of D221 (Figure 6B). This provides an appropriate distance for the formation of another hydrogen bond to consolidate the function of H111 in its binding to K2hPg. An additional weak hydrogen bond with a distance of ~2.9 Å appears in some of the low energy structures, connecting the carbonyl oxygen of H111 and the Hε1 of W235.

The anionic carboxyl groups of E102 and E104, two residues at the beginning of the a2-repeat in KTI55SS1448, capture the guanidinium side chain of R220 in K2hPg. Instead of a stable attraction, the distance between the charged heads of R220 and E102/E104 is variable, and could be as distant as ~4.0 Å (Figure 6D), or as close as 1.8 Å (Figure 6E), in different low energy structures. Only the latter proximity drives strong hydrogen bonds. This elastic feature also applies to the interaction of D114 in KTI55SS1448 and R234 in K2hPg (Figure 6F–G). Such highly variable proximities indicate that these two binding sites in KTI55SS1448 can associate with K2hPg, and easily dissociate, thereby explaining the high off-rate observed in the K2hPg-binding affinity determination of KTI55SS1448 (Figure 4C, Table 3).

From the above results, we conclude that H111 in KTI55SS1448 and the LBS in K2hPg constitute a complex and stable network of interactions, contributing in disparate manners to their molecular recognition. Hence, the activity of the His residue in the RH-motif in KTI55SS1448 presents a largely distinct mechanism from the interactions of K2hPg with VEK75AP53 and AGL55NS88.2.

Discussion

The α-helical content in the A-domain of PAM determines the hPg-binding affinity

Although AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 each bind to K2hPg with a ~300 times lower affinity than VEK75AP53, the reasons behind this effect are different. The small loop of L115N116E117 in AGL55NS88.2 maintains its RH-motif ~2.5 Å away from the LBS of K2hPg for avoidance of possible clashes, while the relatively less structured KTI55SS1448 interacts with K2hPg in a much more variable fashion than other more helical PAM-derived peptides. The question arises as to why different GAS isolates develop such variable A-domains in the corresponding PAMs, with regard to the amino acid composition, the number of tandem a-repeats, and their secondary structures.

The previously reported phylogeny of 175 M-proteins, encompassing all emm patterns, has revealed an evolutionary relationship among these proteins [52]. It can be seen from this tree that PAMs expressed from emm86 strains, which only contain a single a2-repeat (Class II), are evolutionarily divergent from all others [52].

The classification of the SK β-domain shows that most of the PAM-containing strains express cluster 2b-type SKs (SK2b) (Figure 7), as previously reported [53]. However, an emm86 strain, D964, has been demonstrated to express SK2a [54]. Additionally, SS1448, another emm86 strain investigated in this current research, expresses the same SK β-domain as strain D964. Thus, their SKs, at least according to their sequences, are closer to those from Pattern A–C strains that indirectly bind hPg through human fibrinogen. This peculiarity of these two emm86 isolates does not contradict the well-established coinheritance of PAM and SK2b in Pattern D strains, but provides a possibility that they constitute a transition stage from Pattern A–C strains to the Pattern D strains that employ PAM to specifically capture hPg [53]. A third emm86 strain, GLS277, even expresses a PAM with two b-repeats in its B-domain, along with a single a-repeat that is almost identical with that in PAMSS1448 (Supplementary Table S2). Two tandem b-repeats in the B-domain are typical of human fibrinogen-binding M1 and M3-proteins [55]. Although it is not known whether PAMGLS277 is able to associate with human fibrinogen, its special B-domain again reflects an intermediate state of an emm86 strain-derived PAM.

Figure 7. Phylogenetic tree of the SK β-domain.

This unrooted tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method [45] in MEGA7 [46]. Three clusters are designated aside the tree. Both the GAS isolate name and the corresponding emm type (in parentheses) are displayed.

Several structures of different complexes that comprise K2hPg and PAM-derived peptides have hitherto been determined, either by NMR or X-ray crystallography (Figure 8A). An increase in the α-helical content of the PAM A-domain is correlated with an enhancement in the hPg-binding affinity. Unexpectedly, some consensus sequences of PAM A-domains, e.g. LXXL, KNE, RH/RY and DXD, exist in other M-proteins expressed by Pattern A–C strains, e.g. JS101 (emm1), SF370 (emm1), and MGAS315 (emm3) [56], albeit disconnected (Supplementary Table S3). Such M-proteins share a common ancestor with PAMs [52]. Hence, we propose an evolutionary model of the PAM A-domain. By means of substitution and recombination, the discontinuous motifs could be combined to form the first complete PAM A-domain (Figure 8B). Nevertheless, this initial PAM probably exhibited a limited α-helical fraction in its A-domain, even lower than that of KTI55SS1448, which was insufficient for tight binding to hPg.

Figure 8. Structural development of the PAM A-domain.

(A) Typical features of PAMs from different classes are summarized, in terms of hPg-binding affinities, K2hPg-bound complex structures, and SK clusters. (B) Key events with regard to structural changes in the PAM A-domain are illustrated with a correlation to the hPg-binding affinity.

PAM-positive strains subsequently adopt two major strategies to enhance the binding affinity of PAM to hPg, including optimization of the A-domain sequence and recombination with another a-repeat, e.g. Class I and Class III PAMs (Figure 8B). Both strategies serve to increase the α-helical content in the A-domain. However, it is still not known why PAMGLS307 contains five a-repeats in the A-domain (Supplementary Table S2), since two a-repeats are sufficient for PAMs to achieve nanomolar-range binding to hPg. One plausible explanation is that these five a-repeats sufficiently separate the A-domain and the HVR, making it possible for PAMGLS307 to capture two different host proteins through these two regions at the same time.

The evolutionary importance of the His residue in the PAM RH-motif

Concerning the RH-motif, the role of Arg in the interaction between PAM and hPg has been confirmed in multiple studies [13,19–21]. However, the His in this motif shows a more limited function compared with the Arg, and is only involved in a hydrogen bond with the LBS in K2hPg. But, from the viewpoint of evolution, if His did not significantly contribute to hPg-binding, the His following the Arg in the A-domain in most PAMs would not have been preserved. Our study strongly suggests that His in the RH-motif is able to insert into the LBS when mobile loops dominate the PAM A-domain, such as in PAMSS1448. In addition to duality of His side chain in forming hydrogen bonds and electrostatic attractions, His has the potential to develop a strong π–π stacking arrangement with the indole side chains of W225/W235 in hPg, when the two aromatic side chains move to a parallel position. Although the guanidinium cation of Arg appears partially planar, the π–π stacking effect of this residue is inferior to the imidazole side chain of His. This special stacking effect, along with the hydrogen bonding initiated by N108, accounts for an insertion of a neutral His111 into the LBS of K2hPg (Figure 6C).

With the improvement in the K2hPg-binding affinity of the PAM A-domain, the α-helical content in this region increases. All the previously reported structures of VEKAP53/K2hPg clearly suggest that if PAM still utilized His as the major determinant in the interaction with K2hPg, geometric clashes would inevitably occur between these two moieties. In turn, Arg inserts into the LBS instead of His, thereby preventing an energetically unfavorable clash. In this sense, when the A-domain becomes more structured, the importance of His decreases, while the significance of Arg increases. The His residue in the RH-motif is even replaced by Tyr in some PAMs, PAM29486, PAMGLS250, PAMGLS263, and PAMGLS312 (Supplementary Table S2), supporting a reduced significance of this His residue in PAMs containing two a-repeats, i.e. Class I and III PAMs.

The importance of this work is based in the elucidation of the atomic-level binding mechanisms underlying the interactions between the PAM-binding domain of human plasminogen (K2hPg) and Class II PAM-derived peptides that contain only the a2-repeat. In addition, it is also biologically unique and relevant that the α-helical content in the A-domain determines the evolving state of PAMs, which is conducive for binding to hPg, a factor that enhances its virulence. More specifically, for a PAM that exhibits limited α-helices in the A-domain, we provide proof that His of the RH-motif, rather than Arg, inserts into the LBS of K2hPg. Special natural mutations and recombination events are present in some PAMs as well, e.g. substitution of RH to RY and appearance of five a-repeats, but why these PAMs contain such unusual changes needs further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The work was supported by a multi-PI grant (HL013423) to F.J.C., S.W.L., and V.A.P.

Abbreviations

- CSP

chemical shift perturbation

- GAS

Group A Streptococcus pyogenes

- hPg

human plasminogen

- hPm

human plasmin

- LBS

lysine-binding site

- PAM

plasminogen-associated M-protein

- RDC

residual dipolar coupling

- TROSY

transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Data availability

Backbone chemical shift assignments and experimental restraints used in the structure calculations for AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 bound to K2hPg have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB) with accession numbers 30686 and 30687, respectively. The co-ordinates of the calculated structure ensembles, AGL55NS88.2 and KT155SS1448 bound to K2hPg, have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession numbers 6UZ4 and 6UZ5, respectively. The structural co-ordinates of the apo forms of AGL55NS88.2 (6BZJ) and KTI55SS1448 (6BZK) have been deposited in the PDB earlier.

References

- 1.Cole JN, Barnett TC, Nizet V and Walker MJ (2011) Molecular insight into invasive group A streptococcal disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 724–736 10.1038/nrmicro2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker MJ, Barnett TC, McArthur JD, Cole JN, Gillen CM, Henningham A et al. (2014) Disease manifestations and pathogenic mechanisms of group A Streptococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 27, 264–301 10.1128/CMR.00101-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK and Weber M (2005) The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5, 685–694 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70267-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips GN, Flicker PF, Cohen C, Manjula BN and Fischetti VA (1981) Streptococcal M protein: alpha-helical coiled-coil structure and arrangement on the cell surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 4689–4993 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bessen D, Jones KF and Fischetti VA (1989) Evidence for two distinct classes of streptococcal M protein and their relationship to rheumatic fever. J. Exp. Med. 169, 269–283 10.1084/jem.169.1.269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Facklam R, Beall B, Efstratiou A, Fischetti V, Johnson D, Kaplan E et al. (1999) Emm typing and validation of provisional M types for group A streptococci. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5, 247–253 10.3201/eid0502.990209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham MW (2000) Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13, 470–511 10.1128/CMR.13.3.470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bessen DE, Sotir CM, Readdy TL and Hollingshead SK (1996) Genetic correlates of throat and skin isolates of group A streptococci. J. Infect. Dis. 173, 896–900 10.1093/infdis/173.4.896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berge A and Sjobring U (1993) PAM, a novel plasminogen-binding protein from Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 25417–25424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wistedt AC, Kotarsky H, Marti D, Ringdahl U, Castellino FJ, Schaller J et al. (1998) Kringle 2 mediates high affinity binding of plasminogen to an internal sequence in streptococcal surface protein PAM. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 24420–24424 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wistedt AC, Ringdahl U, Müller-Esterl W and Sjøbring U (1995) Identification of a plasminogen-binding motif in PAM, a bacterial surface protein. Mol. Microbiol. 18, 569–578 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cnudde SE, Prorok M, Castellino FJ and Geiger JH (2006) X-ray crystallographic structure of the angiogenesis inhibitor, angiostatin, bound to a peptide from the group A streptococcal surface protein PAM. Biochemistry 45, 11052–11060 10.1021/bi060914j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M, Zajicek J, Geiger JH, Prorok M and Castellino FJ (2010) Solution structure of the complex of VEK-30 and plasminogen kringle 2. J. Struct. Biol. 169, 349–359 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schenone MM, Warder SE, Martin JA, Prorok M and Castellino FJ (2000) An internal histidine residue from the bacterial surface protein, PAM, mediates its binding to the kringle-2 domain of human plasminogen. J. Pept. Res. 56, 438–445 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00810.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanderson-Smith ML, Walker MJ and Ranson M (2006) The maintenance of high affinity plasminogen binding by group A streptococcal plasminogen-binding M-like protein is mediated by arginine and histidine residues within the a1 and a2 repeat domains. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25965–25971 10.1074/jbc.M603846200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loof TG, Deicke C and Medina E (2014) The role of coagulation/fibrinolysis during Streptococcus pyogenes infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 4, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu C, Yuan Y, Zajicek J, Liang Z, Balsara RD, Brito-Robionson T et al. (2018) Contributions of different modules of the plasminogen-binding Streptococcus pyogenes M-protein that mediate its functional dimerization. J. Struct. Biol. 204, 151–164 10.1016/j.jsb.2018.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu C, Yuan Y, Liang Z, Lee SW, Ploplis VA and Castellino FJ (2019) Variations in the secondary structures of PAM proteins influence their binding affinities to human plasminogen. J. Struct. Biol. 206, 193–203 10.1016/j.jsb.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rios-Steiner JL, Schenone M, Mochalkin I, Tulinsky A and Castellino FJ (2001) Structure and binding determinants of the recombinant kringle-2 domain of human plasminogen to an internal peptide from a group A streptococcal surface protein. J. Mol. Biol. 308, 705–719 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quek AJH, Mazzitelli BA, W G, Leung EWW, Caradoc-Davies TT, Lloyd GJ et al. (2019) Structure and function characterization of the a1a2 motifs of Streptococcus pyogenes M-protein in human plasminogen binding. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 3804–3813 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan Y, Ayinuola YA, Singh D, Ayinuola O, Mayfield JA, Quek A et al. (2019) Solution structural model of the complex of the binding regions of human plasminogen with its M-protein receptor from Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Struct. Biol. 208, 18–29 10.1016/j.jsb.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bao YJ, Liang Z, Mayfield JA, Donahue DL, Carothers KE, Lee SW et al. (2016) Genomic characterization of a pattern D Streptococcus pyogenes emm53 isolate reveals a genetic rationale for invasive skin tropicity. J. Bacteriol. 198, 1712–1724 10.1128/JB.01019-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang Z, Stephens M, Ploplis VA, Lee SW and Castellino FJ (2018) Draft genome sequences of six skin isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes. Genome Announc. 6, e00592–e00518 10.1128/genomeA.00592-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMillan DJ, Drèze PA, Vu T, Bessen DE, Guglielmini J, Steer AC et al. (2013) Updated model of group A streptococcus M proteins based on a comprehensive worldwide study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19, E222–E229 10.1111/1469-0691.12134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferretti JJ, McShan WM, Ajdic D, Savic DJ, Savic G, Lyon K et al. (2001) Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 98, 4658–4663 10.1073/pnas.071559398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilsen SL, DeFord ME, Prorok M, Chibber BAK, Bretthauer RK and Castellino FJ (1997) High-level secretion in Pichia pastoris and biochemical characterization of the recombinant kringle 2 domain of tissue-type plasminogen activator. Biotech. Appl. Biochem. 25, 63–74 10.1111/j.1470-8744.1997.tb00415.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nilsen SL, Prorok M and Castellino FJ (1999) Enhancement through mutagenesis of the binding of the isolated kringle 2 domain of human plasminogen to omega-amino acid ligands and to an internal sequence of a streptococcal surface protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22380–22386 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan Y, Zajicek J, Qiu C, Chandrahas V, Lee SW, Ploplis VA et al. (2017) Conformationally organized lysine isosteres in Streptococcus pyogenes M protein mediate direct high-affinity binding to human plasminogen. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 15016–15027 10.1074/jbc.M117.794198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang M, Prorok M and Castellino FJ (2010) NMR backbone dynamics of VEK-30 bound to the human plasminogen kringle 2 domain. Biophys. J. 99, 302–312 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Markley JL, Bax A, Arata Y, Hilbers CW, Kaptein R, Sykes BD et al. (1998) Recommendations for the presentation of NMR structures of proteins and nucleic acids. J. Mol. Biol. 280, 933–952 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salzmann M, Pervushin K, Wider G, Senn H and Wuthrich K (1998) TROSY in triple-resonance experiments: new perspectives for sequential NMR assignment of large proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13585–13590 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salzmann M, Wider G, Pervushin K, Senn H and Wuthrich K (1999) TROSY-type triple-resonance experiments for sequential NMR assignments of large proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 844–848 10.1021/ja9834226 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu G, Kong XM and Sze KH (1999) Gradient and sensitivity enhancement of 2D TROSY with water flip-back, 3D NOESY-TROSY and TOCSY-TROSY experiments. J. Biomol. NMR 13, 77–81 10.1023/A:1008398227519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zwahlen C, Legault P, Vincent SJF, Greenblatt J, Konrat R and Kay LE (1997) Methods for measurement of intermolecular NOEs by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy: application to a bacteriophage N-peptide/boxB RNA complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 6711–6721 10.1021/ja970224q [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ottiger M, Delaglio F and Bax A (1998) Measurement of J and dipolar couplings from simplified two-dimensional NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 131, 373–378 10.1006/jmre.1998.1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williamson MP (2013) Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 73, 1–16 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen Y and Bax A (2013) Protein backbone and sidechain torsion angles predicted from NMR chemical shifts using artificial neural networks. J. Biomol. NMR 56, 227–241 10.1007/s10858-013-9741-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N and Clore GM (2003) The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 160, 65–73 10.1016/S1090-7807(02)00014-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ and Clore GM (2006) Using Xplor-NIH for NMR molecular structure determination. Prog. Nucl. Mag. Res. Sp. 48, 47–62 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2005.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwieters CD, Bermejo GA and Clore GM (2018) Xplor-NIH for molecular structure determination from NMR and other data sources. Protein Sci. 27, 26–40 10.1002/pro.3248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X et al. (2007) Molprobity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W375–W383 10.1093/nar/gkm216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen VB, Arendall WB, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ et al. (2010) Molprobity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 10.1107/S0907444909042073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Zundert GCP, Rodrigues JPGLM, Trellet M, Schmitz C, Kastritis PL, Karaca E et al. (2016) The HADDOCK2.2 web server: user-friendly integrative modeling of biomolecularcomplexes. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 720–725 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Vries SJ, van Dijk M and Bonvin AM (2010) The HADDOCK web server for data-driven biomolecular docking. Nat. Protoc. 5, 883–897 10.1038/nprot.2010.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saitou N and Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar S, Stecher G and Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Serrano VS and Castellino FJ (1992) The role of tryptophan-74 of the recombinant kringle 2 domain of tissue-type plasminogen activator in its w-amino acid binding properties. Biochemistry 31, 3326–3335 10.1021/bi00128a004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Serrano VS and Castellino FJ (1992) The cationic locus on the recombinant kringle 2 domain of tissue-type plasminogen activator that stabilizes its interaction with w-amino acids. Biochemistry 31, 11698–11706 10.1021/bi00162a005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Serrano VS and Castellino FJ (1993) Specific anionic residues of the recombinant kringle domain of tissue-type plasminogen activator that are responsible for stabilization of its interactions with w-amino acid ligands. Biochemistry 32, 3540–3548 10.1021/bi00065a004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Serrano VS and Castellino FJ (1994) Role of the strictly conserved tryptophan-25 residue in the stabilization of the structure and in the ligand binding properties of the kringle 2 domain of tissue-type plasminogen activator. Biochemistry 33, 1340–1344 10.1021/bi00172a008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Serrano VS and Castellino FJ (1994) Involvement of tyrosine-76 of the kringle-2 domain of tissue-type plasminogen activator in its thermal stability and its w-amino acid ligand binding site. Biochemistry 33, 3509–3514 10.1021/bi00178a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanderson-Smith M, De Oliveira DM, Guglielmini J, McMillan DJ, Vu T, Holien JK et al. (2014) A systematic and functional classification of Streptococcus pyogenes that serves as a new tool for molecular typing and vaccine development. J. Infect. Dis. 210, 1325–1338 10.1093/infdis/jiu260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Liang Z, Hsieh HT, Ploplis VA and Castellino FJ (2012) Characterization of streptokinases from group A streptococci reveals a strong functional relationship that supports the coinheritance of plasminogen-binding M protein and cluster 2b streptokinase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 42093–42103 10.1074/jbc.M112.417808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalia A and Bessen DE (2003) Natural selection and evolution of streptococcal virulence genes involved in tissue-specific adaptations. J. Bacteriol. 186, 110–121 10.1128/JB.186.1.110-121.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glinton K, Beck J, Liang Z, Qiu C, Lee SW, Ploplis VA et al. (2017) Variable region in streptococcal M-proteins provides stable binding with host fibrinogen for plasminogen-mediated bacterial invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 6775–6785 10.1074/jbc.M116.768937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beres SB, Sylva GL, Barbian KD, Lei B, Hoff JS, Mammarella ND et al. (2002) Genome sequence of a serotype M3 strain of group A streptococcus: phage-encoded toxins, the high-virulence phenotype, and clone emergence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 10078–10083 10.1073/pnas.152298499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Backbone chemical shift assignments and experimental restraints used in the structure calculations for AGL55NS88.2 and KTI55SS1448 bound to K2hPg have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB) with accession numbers 30686 and 30687, respectively. The co-ordinates of the calculated structure ensembles, AGL55NS88.2 and KT155SS1448 bound to K2hPg, have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession numbers 6UZ4 and 6UZ5, respectively. The structural co-ordinates of the apo forms of AGL55NS88.2 (6BZJ) and KTI55SS1448 (6BZK) have been deposited in the PDB earlier.