Abstract

Objective

Accumulation of amyloid‐β is among the earliest changes in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Amyloid‐β positron emission tomography (PET) and Aβ 42 in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) both assess amyloid‐β pathology in‐vivo, but 10–20% of cases show discordant (CSF+/PET− or CSF‐/PET+) results. The neuropathological correspondence with amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordance is unknown.

Methods

We included 21 patients from our tertiary memory clinic who had undergone both CSF Aβ 42 analysis and amyloid‐β PET, and had neuropathological data available. Amyloid‐β PET and CSF results were compared with neuropathological ABC scores (comprising of Thal (A), Braak (B), and CERAD (C) stage, all ranging from 0 [low] to 3 [high]) and neuropathological diagnosis.

Results

Neuropathological diagnosis was AD in 11 (52%) patients. Amyloid‐β PET was positive in all A3, C2, and C3 cases and in one of the two A2 cases. CSF Aβ 42 was positive in 92% of ≥A2 and 90% of ≥C2 cases. PET and CSF were discordant in three of 21 (14%) cases: CSF+/PET− in a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (A0B0C0), CSF+/PET− in a patient with FTLD‐TDP type B (A2B1C1), and CSF‐/PET+ in a patient with AD (A3B3C3). Two CSF+/PET+ cases had a non‐AD neuropathological diagnosis, that is FTLD‐TDP type E (A3B1C1) and adult‐onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (A1B1C0).

Interpretation

Our study demonstrates neuropathological underpinnings of amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordance. Furthermore, amyloid‐β biomarker positivity on both PET and CSF did not invariably result in an AD diagnosis at autopsy, illustrating the importance of considering relevant comorbidities when evaluating amyloid‐β biomarker results.

Introduction

Among the earliest neuropathological events in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the accumulation and aggregation of amyloid‐β, which occurs decades before symptom onset. 1 Amyloid‐β can aggregate in the brain parenchyma as plaques or in the cerebral vasculature as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Two methods are currently employed to assess amyloid‐β pathology in‐vivo. Aβ 42 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) reflect the concentrations of soluble amyloid‐β, which has been shown to correlate with amyloid‐β deposits in the brain. 2 Alternatively, positron emission tomography (PET) with amyloid‐β radiotracers can be used to visualize cerebral amyloid‐β deposits. 3 , 4 , 5 These two methods are considered interchangeable for the assessment of amyloid pathology in‐vivo and for the diagnosis of AD in both clinical practice and research. 6 , 7

In the majority of cases amyloid‐β PET and CSF are concordant, but in 10–20% of patients they show discordant (CSF+/PET− or CSF‐/PET+) results. 8 , 9 One possible hypothesis for the amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordance is that soluble CSF Aβ 42 decreases before significant fibrillar amyloid‐β deposits can be detected by PET. 10 , 11 Although studies have been performed to compare either amyloid‐β PET or CSF Aβ 42 to neuropathological examination results, 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 so far no head‐to‐head cohort studies have been performed to compare in‐vivo amyloid‐β CSF and PET results to neuropathological findings. Previously, two case reports of patients with discordant amyloid‐β CSF/PET (both CSF+/PET−) and available neuropathology have been published, 12 , 13 in which the negative PET signal was attributed to the lack of neuritic plaques at autopsy. Further investigating the correspondence between amyloid‐β PET, CSF, and neuropathology (“standard of truth”) is important to shed light on the underlying cause of amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordance. Also, if CSF+/PET‐ amyloid‐β status is an indicator of early amyloid‐β pathology, this could be instrumental for future disease modifying therapies. 14 Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the concordance between PET and CSF amyloid‐β status in a sample with available neuropathological results and to characterize the amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordant cases neuropathologically.

Methods

Participants

We retrospectively included 21 autopsy cases from the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort who had undergone both CSF Aβ 42 analysis and amyloid‐β PET during life. Patients visiting our tertiary memory center are screened according to a standardized protocol, 15 including a clinical and neuropsychological evaluation, APOE genotyping, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and a lumbar puncture (LP) for CSF biomarker analysis. Clinical diagnosis is determined during a multidisciplinary meeting.

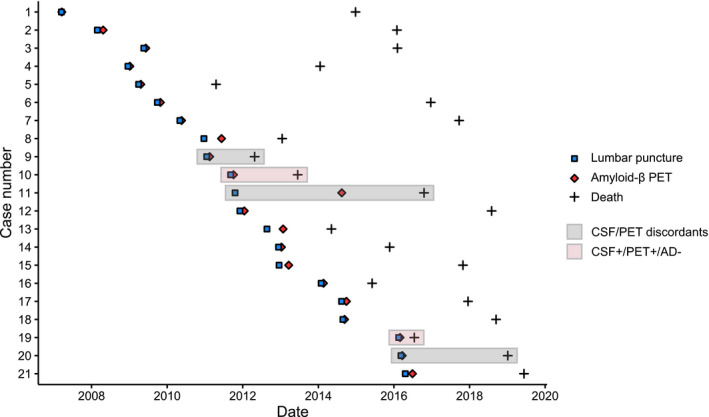

Amyloid‐β PET and CSF analyses were performed between 2007 and 2016 and neuropathological diagnosis was performed between 2011 and 2019 (Fig. 1). In this sample, LP for CSF analysis always preceded amyloid‐β PET and, the median CSF‐PET time was 28 [interquartile range (IQR): 18, 56] days. The median time difference between amyloid‐β PET and patient death was 3.0 (IQR: 1.7, 6.5) years and the time difference between LP and patient death was 3.3 (IQR: 2.0, 6.7) years.

Figure 1.

Time between lumbar puncture, amyloid‐β PET, and patient death. Abbreviations: AD Alzheimer’s disease, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, PET positron emission tomography.

Cerebrospinal fluid

CSF was obtained during life by LP between L3/4 and L5/S1, using a 25‐gauge needle and a syringe. 16 Samples were collected in polypropylene collection tubes and centrifuged at 1800g for 10 min at 4°C and thereafter frozen at −20°C until routine biomarker analysis. Manual analyses of Aβ 42, total tau (t‐tau), and phosphorylated tau (p‐tau) were performed using sandwich ELISAs (Innotest assays: β‐amyloid1‐42, tTAU‐Ag, and PhosphoTAU‐181p; Fujirebio) in the Neurochemistry Laboratory of the Department of Clinical Chemistry of Amsterdam UMC. If two CSF results were available, we used the result closest to the amyloid‐β PET (three cases, all with concordant Aβ 42 status between two samples). As median CSF Aβ 42 values of our cohort have been gradually increasing over the years, we were unable to use the original CSF Aβ 42 values. 17 Therefore, we used CSF Aβ 42 values that have been adjusted for the longitudinal upward drift with a uniform cutoff of 813 pg/mL (<813 pg/mL considered as CSF amyloid‐β positive). 18 Additionally, as it has been previously shown that the ratio of CSF Aβ 42 with CSF (p)tau is superior to CSF Aβ 42 in predicting the diagnosis of AD, 19 we also used a CSF p‐tau/Aβ 42 ratio with a previously validated cutoff of 0.054. 20 This cutoff was obtained by mixture modeling of 2711 CSF results of the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort, similar to previous work. 18

Amyloid‐β positron emission tomography

Amyloid‐β PET was performed using the following PET scanners: ECAT EXACT HR + scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Germany), Gemini TF PET/CT, Ingenuity TF PET‐CT, and Ingenuity PET/MRI (Philips Medical Systems, the Netherlands). We included 15 cases with [11C]Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB), 21 three with [18F]florbetaben, 22 and three with [18F]flutemetamol. 23 Amyloid‐β PET status (positive or negative) was determined by a majority visual read of three reads. All scans were initially read by an expert nuclear medicine physician (BvB, from 2007 to 2016, read 1). In addition, in 2019 the scans were reread for this study by BvB (read 2) and LC (with extensive experience in reading amyloid‐β PET scans, read 3), while being blinded to the results of other visual reads, CSF, and neuropathological results. The three amyloid‐β PET visual reads were concordant (either +/+/+ or −/−/−) in 18 of 21 cases. In the three remaining cases (nr 5, 10, 19), two of the three visual reads were positive, and as such these cases were considered PET positive.

Neuropathology

Autopsies were performed by the Department of Pathology of Amsterdam UMC; location VUmc for the Netherlands Brain Bank or for VUmc. Brain donors or their next of kin signed informed consent regarding the usage of brain tissue and clinical records for research purposes. Brain autopsies and neuropathological diagnosis were performed according to the international guidelines of Brain Net Europe II consortium (http://www.brainnet‐europe.org) and the applicable diagnostic criteria. 24 , 25 For this particular study, every case also without suspicion of AD pathology during life was scored by AR and BB for AD neuropathological changes according to the ABC scoring system by AR and BB, 24 in which the A stands for amyloid‐β Thal phase, 26 B for Braak stage for neurofibrillary tangles, 1 and C for CERAD criteria for neuritic plaques. 27 When present, CAA was classified as Type 1 (including capillaries in the parenchyma) or Type 2 (leptomeningeal/cortical without capillary involvement) and staged according to Thal et al. 28

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using R software (Version 3.6.1). We used descriptive statistics to characterize the sample. We used the Cochrane–Armitage trend test to examine the associations between amyloid‐β biomarkers and the neuropathological ABC scores, 29 which allowed us to compare both PET and CSF to neuropathology as we had only binarized results available for amyloid‐β PET.

Results

Study population

In our sample of 21 cases, 16 (76%) were male and 10 (48%) were carriers of an APOE ε4 allele (Table 1). Mean age at death was 65 ± 8 years and the average last known Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE, median 2.0 years before death) was 20 ± 6. Eleven (52%) patients had a clinical diagnosis of AD, which was in accordance with neuropathological diagnosis in all AD cases. Two cases (4 and 15, both CSF/PET concordant) carried an autosomal‐dominant mutation associated with AD. In 15 (71%) cases CAA (11 CAA‐Type 1, 4 CAA‐Type 2) was observed at neuropathological examination.

Table 1.

Case characteristics.

| Nr | Sex | Age at death | APOE genotype | Clinical diagnosis | CSF Aβ 42 | Amyloid‐β PET | CSF/PET status | ABC | Neuropathology | CAA‐Type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary diagnosis | |||||||||||

| 1 | m | 75 | E4E4 | AD | 810 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A3B3C3 | AD | 2 | |

| 2 | m | 65 | E3E3 | AD | 640 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A3B3C3 | AD | 2 | |

| 3 | m | 65 | E3E3 | CBS | 940 | Negative | CSF‐/PET− | A0B1C0 | FTLD‐TDP type A | – | |

| 4 | f | 43 | E3E3 | AD | 554 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A3B3C3 | AD | 1 | |

| 5 | f | 64 | E4E4 | AD | 619 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A2B2C2 | AD | 1 | |

| 6 | m | 69 | E3E4 | AD | 504 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A3B3C3 | AD | 1 | |

| 7 | m | 76 | E3E4 | FTD | 1110 | Negative | CSF‐/PET− | A1B0C0 | FTLD‐TDP type A | – | |

| 8 | m | 60 | – | Dementia unspecified | 1136 | Negative | CSF‐/PET− | A0B0C0 | Autoimmune encephalitis | – | |

| * | 9 | m | 75 | E3E3 | FTD | 787 | Negative | CSF+/PET− | A2B1C1 | FTLD‐TDP type B | – |

| † | 10 | m | 64 | E4E4 | SD | 739 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A3B1C1 | FTLD‐TDP type E | 1 |

| * | 11 | m | 68 | E3E3 | AD | 828 | Positive | CSF‐/PET+ | A3B3C3 | AD | 2 |

| 12 | m | 68 | E3E3 | Dementia unspecified | 1167 | Negative | CSF‐/PET− | A0B1C0 | LBD | – | |

| 13 | m | 65 | E2E3 | FTD | 1708 | Negative | CSF‐/PET− | A1B1C0 | FTLD/MND‐TDP type B | 1 | |

| 14 | m | 70 | E3E4 | AD | 755 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A3B3C3 | AD | 2 | |

| 15 | f | 62 | E4E4 | AD | 681 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A3B3C3 | AD | 1 | |

| 16 | f | 61 | E3E4 | FTD | 862 | Negative | CSF‐/PET− | A1B0C0 | FTLD‐TDP type E | 1 | |

| 17 | m | 73 | E3E4 | AD | 644 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A3B2C1 | AD | 1 | |

| 18 | m | 53 | E3E3 | AD | 587 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A3B3C3 | AD | 1 | |

| † | 19 | m | 50 | E3E3 | HDLS | 676 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A1B1C0 | Leukodystrophy due to HDLS | 1 |

| * | 20 | f | 65 | E3E3 | Vasculitis | 646 | Negative | CSF+/PET− | A0B0C0 | Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | – |

| 21 | m | 65 | E3E4 | AD | 397 | Positive | CSF+/PET+ | A3B3C3 | AD | 1 |

Asterisks (*) in the first column highlight CSF/PET discordant cases and crosses (†) highlight CSF+/PET + cases with a non‐AD neuropathological diagnosis. Values under 813 pg/mL for CSF Aβ 42 are pathological. Amyloid‐β PET positivity was determined by majority visual read. Neuropathological ABC scoring system entails amyloid‐β Thal (A) phase, Braak (B) stage for neurofibrillary tangles, and CERAD (C) criteria for neuritic plaques. CAA column indicates the neuropathological type of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: Type 1 (capillary) or Type 2 (leptomeningeal/cortical). Abbreviations: AD Alzheimer’s disease, CAA cerebral amyloid angiopathy, CBS corticobasal syndrome, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, FTD frontotemporal dementia, FTLD frontotemporal lobar degeneration, HDLS Adult‐onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids, LBD Lewy body dementia, MND motoneuron disease, PET positron emission tomography, SD semantic dementia.

In vivo amyloid‐β status

Thirteen (62%) cases were defined as amyloid‐β positive based on PET, 14 (67%) based on CSF Aβ 42, and 11 (52%) based on CSF p‐tau/Aβ 42 ratio. In our sample, CSF Aβ 42 and amyloid‐β PET were concordant in 18 (86%) cases. CSF p‐tau/Aβ 42 ratio was concordant with amyloid‐β PET in 17 (81%) cases and with CSF Aβ 42 in 16 (76%) cases.

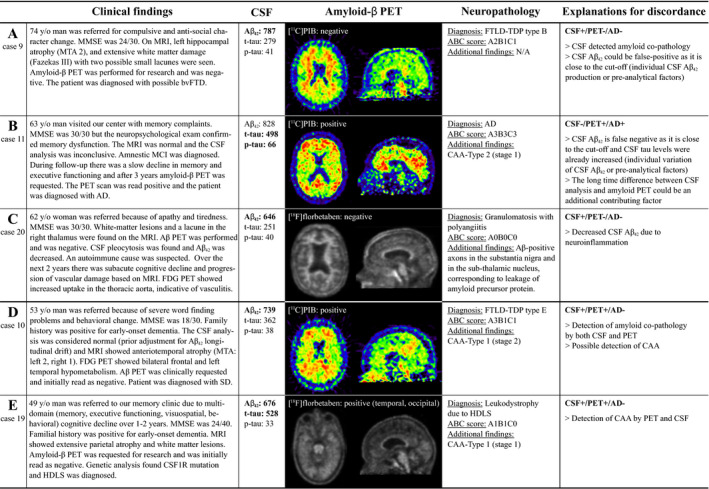

Discordance between amyloid‐β PET, CSF, and neuropathological diagnosis

Of the three discordant cases between CSF Aβ 42 and amyloid‐β PET, two were CSF+/PET‐ (case 9, clinical diagnosis: frontotemporal dementia [neuropathological diagnosis: frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)‐TDP type B, ABC score: A2B1C1] and case 20 with vasculitis [granulomatosis with polyangiitis, A0B0C0], and one was CSF‐/PET+ (case 11 with AD [AD, A3B3C3], Fig. 2A–C). The three amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordant patients all had an APOE ɛ3/ɛ3 genotype. In addition, there were two CSF+/PET + cases with a non‐AD primary neuropathological diagnosis, that is case 10 with semantic dementia [FTLD‐TDP type E, A3B1C1; CAA‐Type 1 stage 2] and case 20 with adult‐onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS) [leukodystrophy due to HDLS, A1B1C0; CAA‐Type 1 stage 1] (Fig. 2D–E).

Figure 2.

Discordance between amyloid‐β CSF, PET, and autopsy. Vignettes illustrating amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordant cases (A,B,C) and CSF+/PET + cases with a non‐AD neuropathological diagnosis (D,E). CSF values for Aβ 42 < 813 pg/mL, for phosphorylated tau (p‐tau) >52 pg/mL, and for total tau (t‐tau) >375 pg/mL are pathological (indicated by bold). Amyloid‐β PET scans in cases 10 and 19 were initially read as amyloid negative, but for this study the scans were considered amyloid positive based on majority visual read. Abbreviations: AD Alzheimer’s disease, CAA cerebral amyloid angiopathy, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, FTD frontotemporal dementia, FTLD frontotemporal lobar degeneration, HDLS Adult‐onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids, MCI Mild cognitive impairment, MMSE Mini‐Mental State Examination, MRI Magnetic resonance imaging, MTA ‐ Medial temporal lobe atrophy, PET positron emission tomography, SD sematic dementia, TDP transactive response DNA‐binding protein.

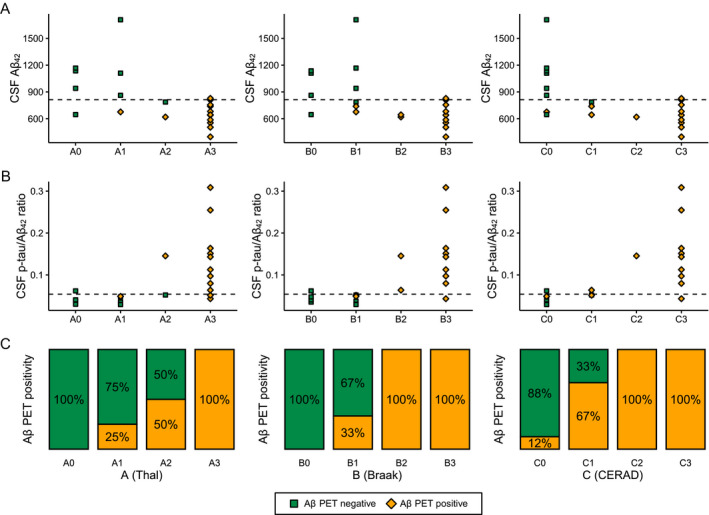

Association between biomarkers and ABC scores

CSF Aβ 42 (Fig. 3A) was positive in 12 of 13 (92%) and CSF p‐tau/Aβ 42 ratio (Fig. 3B) in 10 of 13 (77%) of the A2/A3 cases. Both CSF Aβ 42 and p‐tau/Aβ 42 ratio were positive in 10 of 11 (91%) B2/B3 cases and 9 of 10 (90%) C2/C3 cases. Amyloid‐β PET (Fig. 3C) was positive in one of the two A2 cases, and in all A3 and/or B2/B3 and/or C2/C3 cases. Cochrane trend analyses showed that there is an increasing proportion of biomarker‐positive cases from score 0 to 3 across all ABC scores for amyloid‐β PET (Z‐score = −3.93 for A, Z = −3.81 for B, Z = −3.68 for C, all P < 0.001) and CSF Aβ 42 (Z = −2.92, P = 0.003 for A; Z = −2.46, P = 0.014 for B; Z = −2.60, P = 0.009 for C). In APOE ɛ4 carriers, both CSF Aβ 42 and amyloid‐β PET were positive in all A2/A3 and/or B2/B3 and/or C2/C3 cases. In APOE ɛ4 noncarriers, CSF Aβ 42 was positive in 80% of A2/A3, 75% of B2/B3, and 75% of C2/C3 cases, and amyloid‐β PET was positive in 80% A2/A3 cases and all B2/B3 and/or C2/C3 cases.

Figure 3.

Correspondence of CSF Aβ 42 (A), CSF p‐tau/Aβ 42 ratio (B), and amyloid‐β (Aβ) PET (C) to neuropathological ABC scoring. Neuropathological ABC scoring system entails amyloid‐β Thal phase (A0‐A3), Braak stage for neurofibrillary tangles (B0‐B3), and CERAD criteria for neuritic plaques (C0‐C3). Dashed lines represent cutoffs for CSF Aβ 42 (813 pg/mL) and CSF p‐tau/Aβ 42 ratio (0.054).

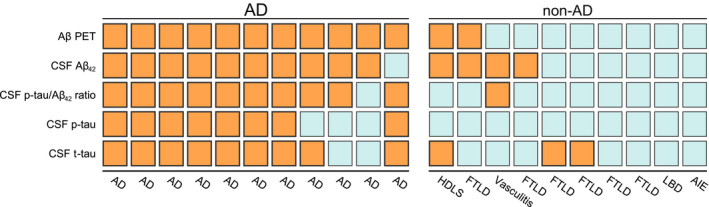

Association between biomarkers and neuropathological diagnosis

Finally, we investigated the association between binarized biomarker results and neuropathological diagnosis. Amyloid‐β PET was positive in all AD cases, but also indicated amyloid‐β pathology in two cases without AD as neuropathological diagnosis (Fig. 4). Both CSF Aβ 42 and p‐tau/Aβ 42 were positive in 10 of 11 AD cases. Decreased CSF Aβ 42 with a normal CSF p‐tau/Aβ 42 ratio was seen in three non‐AD cases (HDLS [A1B1C0]. FTLD‐TDP type B [A2B1C1], FTLD‐TDP type E [A3B1C1]), and one AD case (A3B3C3). There were three cases with a non‐AD neuropathological diagnosis (HDLS, FTLD‐TDP type E, and FTLD/MND‐TDP type B) with normal levels of CSF p‐tau but with increased CSF t‐tau.

Figure 4.

Biomarker status by primary neuropathological diagnosis. Colors indicate binarized status of biomarkers: orange for biomarker positive, blue for biomarker negative. Abbreviations: Aβ Amyloid‐β, AD Alzheimer’s disease, AIE autoimmune encephalitis, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, FTLD frontotemporal lobar degeneration, HDLS Adult‐onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids, PET positron emission tomography.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the concordance between PET and CSF amyloid‐β status in a sample with available neuropathological results in order to enhance our understanding of the amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordant cases. We found that although both CSF and PET generally captured AD pathological change, there was still 14% (3/21) discordance between the two modalities. In our sample, possible reasons for amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordance included neuroinflammation (CSF+/PET− in a case of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, A0B0C0), detection of amyloid‐β co‐pathology (CSF+/PET− in FTLD‐TDP type B, A2B1C1) and additional factors influencing CSF Aβ 42 levels (CSF‐/PET+ in AD, A3B3C3). Additionally, we described two CSF+/PET+ non‐AD cases illustrating that amyloid‐β biomarker positivity on both PET and CSF does not invariably result in an AD diagnosis at autopsy. This highlights that it is important to consider other comorbidities when evaluating the results of amyloid‐β biomarkers, especially since molecular biomarkers for non‐AD neurodegenerative diseases are currently lacking.

Although in the majority of cases, amyloid‐β PET and CSF Aβ 42 show concordant results, 10‐20% discordant CSF/PET status has repeatedly been shown. 8 , 9 , 30 As amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordance rates are highest in patients with early disease, it has been hypothesized that CSF/PET discordance might be partly explained by early decreases of CSF Aβ 42 that precede amyloid‐β depositions visible by PET. 10 , 11 On the other hand, amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordance in patients with dementia could be explained by one modality detecting beginning amyloid‐β co‐pathology in non‐AD cases. 8 To our knowledge, this is the first serial study including patients who have both amyloid‐β PET and CSF Aβ 42 in addition to neuropathological data available. In line with previous in vivo studies, we found a 14% (3/21) CSF/PET discordance rate. We reported a CSF+/PET‐ patient with A2B1C1 FTLD‐TDP type B, where it is feasible that the reduction of CSF Aβ 42 is caused by concomitant amyloid‐β pathology. However, as the Aβ 42 value was relatively close to the cutoff, it is not possible to entirely exclude individual CSF Aβ 42 dynamics (i.e., this patient intrinsically producing less Aβ 42) 31 or preanalytical factors. 32 Previously, two CSF+/PET‐ case reports with available neuropathology have been published. First, a negative PIB PET scan was reported in a 91‐year‐old patient with abnormal CSF Aβ 42 and tau biomarkers with sporadic AD. 12 The negative amyloid‐β PET status was attributed to the absence of a significant amount of fibrillar plaques (i.e., with a fibrillar core that the tracer binds to), although diffuse plaques were present. Second, low PIB PET retention with decreased CSF Aβ 42 was reported in a familial AD case with arctic amyloid precursor protein (APP) mutation, thought to be caused by the lack of fibrillar amyloid‐β plaques characteristic for this mutation. 13 Future studies with neuropathological data are needed to further validate whether amyloid‐β CSF+/PET‐ status is caused by beginning amyloid‐β depositions and explore additional neuropathological substrates for CSF/PET discordance, such as differences in distribution, load, and morphology of amyloid‐β plaques and possible influences of co‐pathologies.

In our sample, there were two cases with amyloid‐β CSF+/PET+ biomarker status who did not meet neuropathological criteria for AD. The first had a diagnosis of FTLD‐TDP type E with a high Thal score but only sparse neuritic plaques (A3B1C1). It is feasible that in this case both biomarkers detected concomitant amyloid‐β co‐pathology as increased PIB PET signal has been shown to be related to fibrillar plaque load even in case of sparse neuritic plaques. 33 , 34 The patient was also diagnosed with CAA‐Type 1 stage 2, which could also contribute to the amyloid positivity, as CAA has been shown to affect both amyloid‐β PET tracer uptake 35 and CSF Aβ 42 levels. 36 The second CSF+/PET+ patient with a low score for AD pathology (A1B1C0) was diagnosed with HDLS, an autosomal‐dominant white matter disease due to mutations in the gene encoding colony‐stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R). 37 Previous case reports of HDLS including CSF analyses have provided no evidence for alterations in Aβ 42 levels. 38 , 39 It is also unlikely that preanalytical assay effects caused the decrease of CSF Aβ 42 in this case as the patient had a separate CSF Aβ 42 sample with decreased Aβ 42 4 months earlier. Similar to the previous patient, CAA‐Type 1 was present and might have contributed to the positive amyloid‐β biomarker status, especially since PET tracer uptake was seen predominantly in the occipital region, a predilection site for CAA pathology. 35 This illustrates that even concordant positivity of two amyloid‐β biomarkers does not always result in a neuropathological diagnosis of AD, and relevant co‐pathologies should always be considered.

There were four cases where CSF Aβ 42 was decreased without a neuropathological diagnosis of AD. In three of them there was neuropathological evidence for amyloid‐β co‐pathology, but we also described a CSF+/PET‐ case with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis), which is in line with literature, as neuroinflammation 40 , 41 as well as infection 42 , 43 have been previously shown to cause decreased CSF Aβ 42 without the presence of AD pathology. This highlights that in select cases, there might be unspecific decreases in CSF Aβ 42 levels without AD, although these cases might be distinguished from AD pathology based on clinical findings and MR imaging. In our particular case, after Aβ immunostaining, Aβ immunoreactive axons were seen, which can be attributed to the leakage of APP that is reported in various conditions such as ischemia, traumatic brain injury and – similar to this case – inflammation. 44 The possible connection of this finding with the decrease in CSF Aβ 42 is unclear, although it is tempting to hypothesize that the loss of APP leads to the interruption of the APP pathway and the reduction of its product Aβ 42 in the CSF. We were unable to find previous case reports of vasculitis with available CSF Aβ 42 analysis, but primary angiitis of the central nervous system has been associated with decreased APP in the CSF, 45 lending support to that speculative theory.

CSF p‐tau/Aβ 42 ratio was slightly more specific than CSF Aβ 42 for capturing the neuropathological diagnosis of AD, which has been previously shown in studies involving living subjects. 19 In the CSF‐/PET+ discordant case we presented, the patient with a clinically advanced AD dementia had a CSF Aβ 42 value just above the cutoff, but CSF p‐tau/Aβ 42 ratio was in the pathological range. In this case, CSF Aβ 42 was likely false negative, possibly due to individual differences in CSF dynamics, as both CSF t‐tau and p‐tau were already increased. This also highlights the advantage of using continuous measurements as opposed to binarized data, as the distance from cutoff includes additional information. Although (p)tau/Aβ 42 ratio may be superior to Aβ 42 when predicting clinically advanced disease with increased (p)tau levels, this may hamper the detection of merely amyloid‐β pathology, where tau tangle pathology has not yet begun. This may become clinically significant if anti‐amyloid treatment arrives in the future. Finally, we reported an isolated increase in CSF t‐tau with normal CSF p‐tau levels in three non‐AD cases (two FTLD and one HDLS). Although CSF t‐tau and p‐tau are highly correlated, this finding supports the notion that CSF t‐tau can increase in other brain pathologies 46 and CSF p‐tau is more AD specific. 47

The primary strength of our study is the availability of two amyloid‐β biomarkers and a neuropathological assessment in a relatively large patient cohort that allowed us to compare the two in vivo amyloid‐β biomarkers to neuropathological change. Although PET and CSF were usually performed close in time, there was a median 3‐year delay between the amyloid‐β biomarkers and autopsy, as is often the case with studies involving in‐vivo biomarkers and autopsy data. While this might have impacted our results, a major change over 3 years is unlikely, given the remarkably slow course of AD. 48 We used standardized uptake value ratio images for PET visual read, which could have an impact on our results as non‐displaceable binding potential images have been shown to be more reliable in detecting early amyloid‐β pathology. 49 , 50 Another limitation is that we included subjects from the year 2006, and over time technologic advancement has taken place, leading to both increased image quality of PET scans and understanding of preanalytical factors influencing CSF (leading to longitudinal drift of median values, in our cohort). Finally, correcting CSF Aβ 42 values with CSF Aβ 40 has been shown to account for the individual variation in the production of amyloid‐β. 51 As CSF Aβ 40 values were only available for seven patients (and none of them were among the discordant cases), we did not include Aβ 42/40 ratio in our analyses.

In conclusion, our findings illustrate a range of reasons for the amyloid‐β CSF/PET discordance, and that even concordant amyloid‐β biomarker positivity accurately reflecting amyloid‐β pathology does not always equal a definite neuropathological diagnosis of AD. Thus, it is important to consider comorbidities as well as other neurodegenerative diseases when using amyloid‐β biomarkers for clinical diagnosis, especially since molecular biomarkers for non‐AD neurodegenerative diseases are currently lacking.

Authors' Contributions

JR, RO, FB, and PS conceived the study and designed the protocol. JR performed statistical analysis, analyzed/interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript. RO and FB provided overall study supervision. JR, BB, LC, RO, and FB participated in writing the manuscript. LC and BvB did the visual reads of the amyloid‐β PET scans. BB and AR were responsible for neuropathological evaluation. CT, AR, BvB, and PS had a major role in the acquisition of data, and critically revised and edited the manuscript for intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

BB and AR received funding of the NIH (R01AG061775). CT received grants from the European Commission, the Dutch Research Council (ZonMW), Association of Frontotemporal Dementia/Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, The Weston Brain Institute, Alzheimer Netherlands. CT has functioned in advisory boards of Roche, received nonfinancial support in the form of research consumables from ADx Neurosciences and Euroimmun, performed contract research or received grants from Probiodrug, Biogen, Esai, Toyama, Janssen prevention center, Boehringer, AxonNeurosciences, EIP farma, PeopleBio, Roche. BvB received research support from ZON‐MW, AVID radiopharmaceuticals, CTMM, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. BvB is a trainer for Piramal and GE; he receives no personal honoraria. PS has received consultancy/speaker fees (paid to the institution) from Biogen, People Bio, Roche (Diagnostics), Novartis Cardiology. PS is PI of studies with Vivoryon, EIP Pharma, IONIS, CogRx, AC Immune, and Toyama. The funding sources were not involved in the writing of this article or in the decision to submit it for publication. JR, LC, RO, and FB report no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The institutional review board of the VU University Medical Center approved all studies from which the current data were gathered and retrospectively analyzed. All patients provided written informed consent for their data to be used for research purposes.

The Alzheimer Center Amsterdam is supported by Alzheimer Nederland and Stichting VUmc fonds. Research performed at the Alzheimer Center Amsterdam is part of the neurodegeneration research program of Amsterdam Neuroscience. JR would like to thank Sergei Nazarenko, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and the North Estonia Medical Centre for their contribution to his professional development.

Funding Information

The Alzheimer Center Amsterdam is supported by Alzheimer Nederland and Stichting VUmc fonds. Research performed at the Alzheimer Center Amsterdam is part of the neurodegeneration research program of Amsterdam Neuroscience.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Alzheimer Nederland and Stichting VUmc grant .

References

- 1. Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer‐related changes. Acta Neuropathol 1991;82:239–259. 10.1007/BF00308809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Strozyk D, Blennow K, White LR, Launer LJ. CSF Abeta 42 levels correlate with amyloid‐neuropathology in a population‐based autopsy study. Neurology 2003;60:652–656. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000046581.81650.D0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ikonomovic MD, Klunk WE, Abrahamson EE, et al. Post‐mortem correlates of in vivo PiB‐PET amyloid imaging in a typical case of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2008;131:1630–1645. 10.1093/brain/awn016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Curtis C, Gamez JE, Singh U, et al. Phase 3 trial of flutemetamol labeled with radioactive fluorine 18 imaging and neuritic plaque density. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:287–294. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sabri O, Sabbagh MN, Seibyl J, et al. Florbetaben PET imaging to detect amyloid beta plaques in Alzheimer’s disease: phase 3 study. Alzheimer’s Dement 2015;11:964–974. 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA‐AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2018;14:535–562. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2011;7:263–269. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Wilde A, Reimand J, Teunissen CE, et al. Discordant amyloid‐β PET and CSF biomarkers and its clinical consequences. Alzheimers Res Ther 2019;11:78 10.1186/s13195-019-0532-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ewers M, Mattsson N, Minthon L, et al. CSF biomarkers for the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a large‐scale international multicenter study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015;11:1306–1315. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palmqvist S, Schöll M, Strandberg O, et al. Earliest accumulation of β‐amyloid occurs within the default‐mode network and concurrently affects brain connectivity. Nat Commun 2017;8: 1214 10.1038/s41467-017-01150-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vlassenko AG, McCue L, Jasielec MS, et al. Imaging and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in early preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2016;80:379–387. 10.1002/ana.24719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cairns NJ, Ikonomovic MD, Benzinger T, et al. Absence of Pittsburgh compound B detection of cerebral amyloid β in a patient with clinical, cognitive, and cerebrospinal fluid markers of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1557–1562. 10.1001/archneurol.2009.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scholl M, Wall A, Thordardottir S, et al. Low PiB PET retention in presence of pathologic CSF biomarkers in Arctic APP mutation carriers. Neurology 2012;79:229–236. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825fdf18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hardy J, Bogdanovic N, Winblad B, et al. Pathways to Alzheimer’s disease. J Intern Med 2014;275:296–303. 10.1111/joim.12192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Der Flier WM, Pijnenburg YAL, Prins N, et al. Optimizing patient care and research: the Amsterdam dementia cohort. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2014;41:313–327. 10.3233/JAD-132306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Engelborghs S, Niemantsverdriet E, Struyfs H, et al. Consensus guidelines for lumbar puncture in patients with neurological diseases. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit 2017;8:111–126. 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schindler SE, Sutphen CL, Teunissen C, et al. Upward drift in cerebrospinal fluid amyloid‐β 42 assay values for more than 10 years. Alzheimer’s Dement 2018;14:62–70. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.06.2264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tijms BM, Willemse EAJ, Zwan MD, et al. Unbiased approach to counteract upward drift in cerebrospinal fluid amyloid‐β 1–42 analysis results. Clin Chem 2018;64:576–585. 10.1373/clinchem.2017.281055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duits FH, Teunissen CE, Bouwman FH, et al. The cerebrospinal fluid “Alzheimer profile”: easily said, but what does it mean? Alzheimer’s Dement 2014;10:713–723.e2. 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Willemse EAJ, Tijms BM, van Berckel BNM, Scheltens P, Teunissen CE. Optimal use of cerebrospinal fluid amyloid‐beta(1–42) in the memory clinic: use of biomarker ratios across immunoassays. (in prep).

- 21. Ossenkoppele R, Prins ND, Pijnenburg YAL, et al. Impact of molecular imaging on the diagnostic process in a memory clinic. Alzheimer’s Dement 2013;9:414–421. 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Wilde A, van der Flier WM, Pelkmans W, et al. Association of amyloid positron emission tomography with changes in diagnosis and patient treatment in an unselected memory clinic cohort. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:1062 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zwan MD, Bouwman FH, Konijnenberg E, et al. Diagnostic impact of [18F]flutemetamol PET in early‐onset dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther 2017;9:2 10.1186/s13195-016-0228-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 2012;123:1–11. 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mackenzie IRA, Neumann M, Bigio EH, et al. Nomenclature and nosology for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an update. Acta Neuropathol 2010;119:1–4. 10.1007/s00401-009-0612-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of Aβ‐deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 2002;58:1791–1800. 10.1212/WNL.58.12.1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1991;41:479 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Rüb U, et al. Two types of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2002;61:282–293. 10.1093/jnen/61.3.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Armitage P. Tests for linear trends in proportions and frequencies. Biometrics 1955;11:375 10.2307/3001775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reimand J, Collij L, Scheltens P, et al. Amyloid‐beta CSF/PET discordance vs tau load 5 years later: it takes two to tangle. medRxiv [preprint]. 2020. 10.1101/2020.01.29.20019539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hansson O, Lehmann S, Otto M, et al. Advantages and disadvantages of the use of the CSF Amyloid β (Aβ) 42/40 ratio in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2019;11:34 10.1186/s13195-019-0485-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hansson O, Mikulskis A, Fagan AM, et al. The impact of preanalytical variables on measuring cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis: a review. Alzheimer’s Dement 2018;14:1313–1333. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lowe VJ, Lundt ES, Albertson SM, et al. Neuroimaging correlates with neuropathologic schemes in neurodegenerative disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2019;15:927–939. 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murray ME, Lowe VJ, Graff‐Radford NR, et al. Clinicopathologic and 11 C‐Pittsburgh compound B implications of Thal amyloid phase across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Brain 2015;138:1370–1381. 10.1093/brain/awv050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johnson KA, Gregas M, Becker JA, et al. Imaging of amyloid burden and distribution in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol 2007;62:229–234. 10.1002/ana.21164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Charidimou A, Friedrich JO, Greenberg SM, Viswanathan A. Core cerebrospinal fluid biomarker profile in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 2018;90:e754–e762. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhuang L‐P, Liu C‐Y, Li Y‐X, et al. Clinical features and genetic characteristics of hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids due to CSF1R mutation: a case report and literature review. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:11 10.21037/atm.2019.12.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Levin J, Tiedt S, Arzberger T, et al. Diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids: biopsy findings and a novel mutation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2014;122:113–115. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Spitzer P, Kohl Z, Golitz P, et al. Biochemical markers of neurodegeneration in hereditary diffuse leucoencephalopathy with spheroids. Case Rep 2014;2014:bcr2012008510 10.1136/bcr-2012-008510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Trysberg E, Höglund K, Svenungsson E, et al. Decreased levels of soluble amyloid beta‐protein precursor and beta‐amyloid protein in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2004;6:129–136. 10.1186/ar1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mori F, Rossi S, Sancesario G, et al. Cognitive and cortical plasticity deficits correlate with altered amyloid‐β CSF levels in multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011;36:559–568. 10.1038/npp.2010.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Krut JJ, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid Alzheimer’s biomarker profiles in CNS infections. J Neurol 2013;260:620–626. 10.1007/s00415-012-6688-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mattsson N, Bremell D, Anckarsäter R, et al. Neuroinflammation in Lyme neuroborreliosis affects amyloid metabolism. BMC Neurol 2010;10:51 10.1186/1471-2377-10-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hayashi T, Ago K, Nakamae T, et al. Two different immunostaining patterns of beta‐amyloid precursor protein (APP) may distinguish traumatic from nontraumatic axonal injury. Int J Legal Med 2015;129:1085–1090. 10.1007/s00414-015-1245-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ruland T, Wolbert J, Gottschalk MG, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of neuronal proteins are reduced in primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Front Neurol 2018;9:1–9. 10.3389/fneur.2018.00407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schöll M, Maass A, Mattsson N, et al. Biomarkers for tau pathology. Mol Cell Neurosci 2019;97:18–33. 10.1016/j.mcn.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Olsson B, Lautner R, Andreasson U, et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:673–684. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00070-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, et al. Amyloid β deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:357–367. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70044-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Collij LE, Konijnenberg E, Reimand J, et al. Assessing amyloid pathology in cognitively normal subjects using 18 F‐flutemetamol PET: comparing visual reads and quantitative methods. J Nucl Med 2019;60:541–547. 10.2967/jnumed.118.211532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van Berckel BNM, Ossenkoppele R, Tolboom N, et al. Longitudinal amyloid imaging using 11C‐PiB: methodologic considerations. J Nucl Med 2013;54:1570–1576. 10.2967/jnumed.112.113654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lewczuk P, Matzen A, Blennow K, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42/40 corresponds better than Aβ42 to amyloid PET in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2016;55:813–822. 10.3233/JAD-160722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]