Abstract

Hyperprolactinemia (hPRL) often poses a diagnostic dilemma due to the presence of macroprolactin. Understanding the prevalence of macroprolactinemia (mPRL) has an important implication in managing patients with hPRL. The primary aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of mPRL globally and to explore selected factors influencing the prevalence estimate. Studies with original data related to the prevalence of mPRL among patients with hPRL from inception to March 2020 were identified, and a random effects meta-analysis was performed. Of the 3770 records identified, 67 eligible studies from 27 countries were included. The overall global prevalence estimate was 18.9% (95% CI: 15.8%, 22.1%) with a substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 95.7%). The highest random effects pooled prevalence was observed in the African region (30.3%), followed by Region of the Americas (29.1%), European (17.5%), Eastern Mediterranean (13.9%), South-East Asian (12.7%), and Western Pacific Region (12.6%). Lower prevalence was observed in studies involving both sexes as compared to studies involving only female participants (17.1% vs. 25.4%) and in more recent studies (16.4%, 20.4%, and 26.5% in studies conducted after 2009, between 2000 and 2009, and before 2000, respectively). The prevalence estimate does not vary according to the age group of study participants, sample size, and types of polyethylene glycol (PEG) used for detection of macroprolactin (PEG 6000 or PEG 8000). With macroprolactin causing nearly one-fifth of hPRL cases, screening for mPRL should be made a routine before an investigation of other causes of hPRL.

Keywords: macroprolactin, macroprolactinemia, big-big prolactin, prolactin, hyperprolactinemia, prevalence, meta-analysis

1. Introduction

Prolactin (PRL) is a hormone secreted by lactotroph cells within the adenohypophysis. PRL is synthesized as a prehormone with a molecular weight of 26 kDa [1]. PRL exists in different forms in human serum. The predominant form is monomeric PRL (little PRL) with a molecular mass of 23 kDa. The other forms include dimeric PRL (big PRL) with a molecular mass of 48–56 kDa, and another form is polymeric PRL, also known as macroprolactin (big-big PRL), with molecular mass >150 kDa. In the normal sera, monomeric PRL accounts for 80–95% of the total PRL, dimeric PRL makes up <10%, and macroprolactin accounts for a small amount of less than 1% of the total PRL [2].

The monomeric PRL is known to be biologically and immunologically active, and when it is in excess, it will cause hyperprolactinemia (hPRL) [2]. When the serum of a patient with hPRL contains mostly macroprolactin, the condition is termed macroprolactinemia (mPRL) [3,4]. In up to 90% of cases, macroprolactin is composed of a complex formed by an IgG and monomeric PRL [4,5,6]. Macroprolactin has a prolonged clearance rate like that of immunoglobulins [7].

Macroprolactin is confined to the vascular system and has limited access to the PRL receptor of target organs owing to limited bioactivity in vivo resulting in asymptomatic hPRL [8,9]. In true hPRL, the common clinical syndromes include galactorrhoea, oligomenorrhoea, or amenorrhoea, and infertility in women and reduced libido, oligospermia or impotence or both, and galactorrhoea in men but not in mPRL. However, it causes diagnostic confusion when it is coincidentally associated with hyperprolactinemic syndrome’s non-specific symptoms. In these circumstances, the symptoms may be mistakenly attributed to true hPRL [10,11]. Therefore, the differentiation between true hPRL and mPRL cannot be made solely based on clinical symptoms. Although macroprolactin is generally biologically inactive, it can be measured by almost all immunoassays for PRL [7,12,13,14]. This may lead to misdiagnosis and unnecessary medical and surgical intervention [15,16] or delayed diagnosis, and inappropriate treatment [17,18].

Screening of hPRL sera for the presence of misleading concentrations of mPRL must be included in the routine investigation of all hyperprolactinemic patients. The reference method for the determination of macroprolactin is gel filtration chromatography (GFC), which allows quantitation of all high molecular mass forms of PRL and an estimate of their molecular mass. Although the GFC method is accurate and reproducible, it is expensive, labor-intensive, and time-consuming. Many alternative techniques have been described based on immunoassay of serum PRL before and after removal of macroprolactin by ultrafiltration, immunoadsorption of IgG species with protein A, protein G, or anti-human IgG and precipitation with polyethylene glycol (PEG) [19,20,21].

PEG precipitation is the best, most widely used method and recommended worldwide for detecting macroprolactin as this method is reproducible, easily performed, and effective. One limitation of PEG precipitation has been reported in which the presence of PEG in the sample can interfere with some PRL immunoassay procedures [22]. To overcome this problem, each laboratory must establish its reference intervals derived from PEG-treated sera of healthy individuals [11,15].

Although many studies have reported the prevalence of mPRL among hPRL using various immunoassay analyzers, different methods of detection for mPRL, different cut-off PRL levels for the screening of mPRL, and various cut-off recovery post-PEG, a systematic literature review on the prevalence of mPRL had not been performed to date. The primary objectives of this study were to conduct a systematic literature review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of mPRL, summarize the findings of these studies, and explore selected factors that may influence prevalence estimates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist. The protocol was registered in the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42019123884).

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategies

Two investigators (N.A.A.C.S. and N.M.Y.) extensively searched online international databases subscribed by our institutional library (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library Database, SAGE, Scopus, EBSCO Academic Search Complete, EBSCO PsycINFO, ProQuest, Elsevier, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and Emerald Insight) from inception to 30 March 2020. The search terms were MeSH terms and text words linked to mPRL and hPRL using a combination of the following search terms: “polymeric prolactin”, “macroprolactin”, “macroprolactinemia”, “macroprolactinaemia”, “big big prolactin”, “BBPRL”, “big prolactin”, “BPRL”, “hyperprolactinemia”, “hyperprolactinaemia”, “elevated prolactin”, “excess prolactin”, “high prolactin”. The search strategy was tested in two databases (PubMed, Elsevier ScienceDirect) and was further refined based on its ability to retrieve known relevant studies according to each database. Forward and backward reference chaining of included studies were carried out in which the reference lists from the included papers were searched to identify other relevant information. A systematic literature search of multiple databases using search terms as listed above was conducted to search for articles published in peer-reviewed literature, clinical trial registries, conference proceedings, and gray literature. To maximize sensitivity rather than the specificity of the literature search, we did not include “prevalence”, “incidence”, “proportion”, or “frequency” as the search term.

2.3. Study Eligibility

Two investigators (N.A.A.C.S. and N.M.Y.) independently screened all titles and abstracts from the initial search results and full-text articles identified from the first-stage screening (titles and abstract). Studies that reported primary data on the prevalence of mPRL from inception to 30 March 2020 were included. Searches were conducted in English, and publications in all languages were considered. Any observational (cross-sectional, cohort, longitudinal) studies were eligible for inclusion if the study reported the target population of interest (hPRL patients regardless of cause) and on study outcomes (prevalence or frequency of mPRL among hPRL patients). Experimental (randomized, non-randomized) trials, case-control studies, ecological studies, case reports, studies that did not involve human participants (animal, in vitro studies), book chapters, narrative reviews, and protocol studies were excluded.

2.4. Data Extraction

Search results from each database were downloaded in a standardized tag format developed by Research Information Systems (.ris) or NBIB format (.nbib). In databases that do not allow all search results to be downloaded at once (e.g., Google Scholar, EMBASE), search results were downloaded in partitions and later merged in Microsoft Windows command prompt (cmd) using this command: “copy *.ris mergefile.ris”. The search results were then imported into Zotero software to remove duplicates. After removing duplicates, the search result was exported as Microsoft Excel.csv format and later converted to .xlsx format.

Preliminary screening of titles and abstracts was conducted by two investigators (N.A.A.C.S. and N.M.Y.) to identify potential articles of interest. The full text of potentially eligible studies was retrieved and re-assessed for inclusion/exclusion criteria. Assessment of eligibility was made in duplication and independently to avoid bias in study selection. The degree of change-adjusted agreement between the two review authors was noted and statistically assessed by Kappa statistics. Conflicts in study identification were resolved by discussion and in conjunction with a third investigator (J.O.) to obtain 100% agreement with the final decision. A detailed assessment of why studies were excluded after the full-text review was prepared.

After study identification, data from included studies were abstracted by two investigators (N.A.A.C.S. and N.M.Y.) using a standardized pre-design and pre-piloted electronic data abstraction form in Microsoft Excel format to assess study quality and for evidence synthesis. Data abstractions were conducted independently to minimize the risk of errors. The information abstracted included: author’s name, publication year, country, region, study design, study population, operational definition of hPRL, diagnostic test for hPRL, diagnostic test for mPRL, the cut-off point for the diagnostic test used for diagnosis of mPRL, number of study participants (hPRL), and number of participants with the outcome of interest (mPRL).

When there were multiple publications of the same study, data were extracted from each publication, but only the most “complete” and up-to-date data were included. The data were analyzed following resolution of overlaps in the extracted data. The literature search and screening output were reported in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) study flow diagram.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The quality of each included study (assessment of bias) was critically and objectively appraised by two investigators (N.A.A.C.S. and N.M.Y.) independently and in duplicate, using adapted quality assessment tool for prevalence studies [23]. The tool consists of 10 items addressing three domains of bias (selection, nonresponse, measurement bias) and a summary score classifying the study as low, medium, or high risk of bias. All disagreement was resolved by discussion with the involvement of a third review author (J.O.).

2.6. Statistical Analyses

The qualitative synthesis omitted studies with a high risk of bias. Aggregate level data was used for data synthesis, and a summary of all the findings in the included studies was provided. A meta-analysis of the prevalence was conducted using the metaprop module in STATA software version 14.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). A random effects meta-analysis was performed to obtain the pooled prevalence with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and forest plot. Confidence intervals for the pooled estimates were calculated after the Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation. The possibility of statistical heterogeneity among included studies was estimated by Cochran’s Q (reported with a χ2 and p-value) and the I2 statistic. The I2 statistic describes the fraction of the variability in effect that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. A p-value of less than 0.10, rather than the conventional level of 0.05, is used to determine statistical significance of heterogeneity.

Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s test and funnel plot. Sensitivity analysis was performed by eliminating individual studies one at a time. Alteration in the pooled prevalence and the 95% CI were examined to assess the stability of the meta-analysis. Subgroup analyses were conducted according to region, sex, age group, year period when the study was published, and types of PEG used for the detection of macroprolactin. The random effect pooled prevalence estimate with the corresponding 95% CI, the within-group heterogeneity, and the between-group heterogeneity tests were reported. A p-value for this test of less than 0.10 indicates a statistically significant subgroup (interaction) effect. As an extension to subgroup analysis, individual variable meta-regression was conducted to investigate the effect of continuous study characteristics (sample size and year of studies) and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered for statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

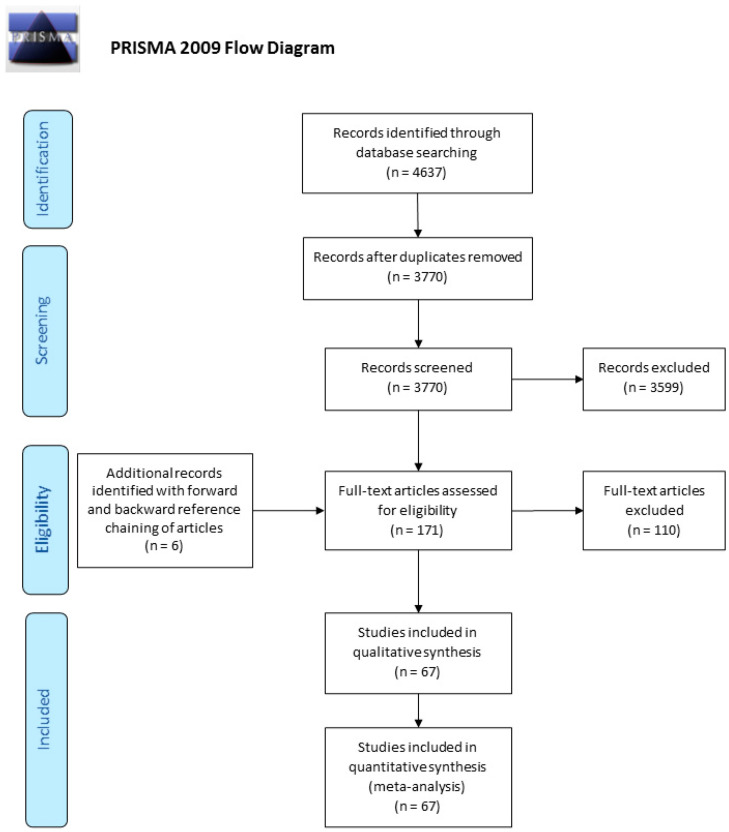

After removal of duplicates, 3770 records were screened by their titles and abstracts from which 171 articles qualified for a full-text review. Forward and backward reference chaining of articles during full-text review identified six extra articles. In total, 177 articles were assessed for eligibility in full text, and from these, 67 studies reported on the prevalence of mPRL among patients with hPRL and fulfilled other eligibility criteria (Figure 1: Flow of information diagram). The final sample of 67 studies published between 1985 and 2019 from 27 countries was included, involving 16,951 patients with hPRL. The largest proportion of studies came from the European Region (37 studies, 55.2%) followed by Region of the Americas (14 studies, 20.9%), Western Pacific Region (7 studies, 10.4%), Eastern Mediterranean Region (4 studies, 6.0%), South-East Asia Region (3 studies, 4.5%), and African Region (2 studies, 3.0%).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart.

Large heterogeneity between studies was observed concerning the method of hPRL and mPRL detection, as listed in Table 1. The majority of the included studies (56 studies) utilized a single method to detect hPRL, eight utilized a combination of two methods, two studies utilized a combination of three methods, and one study utilized a combination of four methods. The majority of the studies (28 studies) used Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (CLIA) as the method of detecting hPRL, and 24 studies used the Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay (ECLIA) method. For the diagnosis of mPRL, 47 studies used a single method, 20 studies used a combination of two methods, and one study used a combination of three methods. PEG is the most used method for diagnosis of mPRL, 47 studies used PEG 6000, 6 studies used PEG 8000, and 10 studies used PEG but did not specify whether it was PEG 6000 or PEG 8000. GFC was used in 20 studies for the diagnosis of mPRL. Various recovery cut-off points were used for diagnosis of mPRL, and most of the studies used <40% PRL recovery as the cut-off.

Table 1.

Details of studies on the prevalence of macroprolactinemia among patients with hyperprolactinemia, sorted by year.

| No | Author | Year | Country | Design | Age group | Sex | Specific Condition of hPRL | Method of PRL Detection | Method of Macroprolactin Detection | Cut off Recovery (%) | n hPRL | n mPRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Larrea et al. [24] | 1985 | Mexico | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | No | RIA | GFC | - | 12 | 3 |

| 2 | Fahie-Wilson et al. [25] | 1997 | UK | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | FIA, EIA, CLIA | PEG 6000, GFC | - | 69 | 17 |

| 3 | Vieira et al. [26] | 1998 | Brazil | cross-sectional | Unspecified | Both | No | FIA | PEG 6000, GFC | 30 | 1220 | 513 |

| 4 | Olukoga et al. [27] | 1999 | UK | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | FIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 188 | 29 |

| 5 | Blanco-Favela et al. [28] | 2001 | Mexico | cross-sectional | Teenage | Both | SLE patients | IRMA | PEG, Protein G Sepharose | - | 32 | 7 |

| 6 | Leaños-Miranda et al. [29] | 2001 | Mexico | cross-sectional | Unspecified | Both | SLE patients | IRMA | PEG 6000, GFC | - | 43 | 14 |

| 7 | Sánchez-Eixerés et al. [30] | 2001 | Spain | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG 6000, GFC | 40 | 211 | 19 |

| 8 | Schiettecatte et al. [19] | 2001 | Belgium | cross-sectional | Unspecified | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG 6000, GFC | 50 | 175 | 38 |

| 9 | Leslie et al. [31] | 2001 | UK | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | No | FIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 1225 | 322 |

| 10 | Smith et al. [32] | 2002 | UK | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | EIA, CLIA, ECLIA, IFMA | PEG, GFC | - | 300 | 71 |

| 11 | Hauache et al. [33] | 2002 | Brazil | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | FIA | PEG 6000, GFC | 30 | 113 | 52 |

| 12 | Sapin et al. [34] | 2002 | France | cross-sectional | All age | Male | No | CLIA, ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 34 | 14 |

| 13 | Vallette-Kasic et al. [35] | 2002 | France | cross-sectional | All age | Both | No | CLIA | GFC | - | 1106 | 106 |

| 14 | Toldy et al. [36] | 2003 | Hungary | cross-sectional | All age | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 270 | 62 |

| 15 | Strachan et al. [37] | 2003 | UK | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 50 | 273 | 58 |

| 16 | García Menéndez et al. [38] | 2003 | Spain | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 50 | 195 | 39 |

| 17 | García et al. [39] | 2004 | Argentina | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | SLE patients | IRMA | PEG 6000, GFC | - | 34 | 7 |

| 18 | Escobar-Morreale et al. [40] | 2004 | USA | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | Hyperandrogenic | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 8 | 4 |

| 19 | Rivero et al. [41] | 2004 | Spain | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000, GFC | 54 | 96 | 11 |

| 20 | Galoiu et al. [42] | 2005 | Romania | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | IRMA, ECLIA | GFC, protein A precipitation | - | 84 | 16 |

| 21 | Germano et al. [43] | 2005 | Italy | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 172 | 37 |

| 22 | Gibney et al. [18] | 2005 | Ireland | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | FIA | PEG 8000 | - | 2089 | 453 |

| 23 | Theunissen et al. [44] | 2005 | Belgium | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | EIA, RIA, ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 77 | 14 |

| 24 | Hattori et al. [45] | 2006 | Japan | cross-sectional | Teenage and adult | Both | No | ELISA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 159 | 18 |

| 25 | Alfonso et al. [46] | 2006 | USA | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG | 50 | 82 | 40 |

| 26 | Álvarez-Vázquez et al. [47] | 2006 | Spain | cross-sectional | Teenage and adult | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 75 | 228 | 22 |

| 27 | Rivas-Espinosa et al. [48] | 2006 | Mexico | others | Adult | Both | No | EIA | PEG 6000 | 50 | 30 | 7 |

| 28 | Donadio et al. [49] | 2007 | Italy | retrospective cohort | Adult | Both | No | FIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 135 | 57 |

| 29 | Jokar et al. [50] | 2008 | Iran | cross-sectional | Teenage and adult | Both | SLE patients | RIA | PEG | 40 | 9 | 5 |

| 30 | Baǧdatoǧlu et al. [51] | 2008 | Turkey | cross-sectional | All age | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 124 | 13 |

| 31 | Vilar et al. [52] | 2008 | Brazil | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | CLIA, IRMA | PEG | 30 | 1234 | 115 |

| 32 | Alfadda et al. [53] | 2008 | Saudi Arabia | retrospective cohort | All age | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 156 | 10 |

| 33 | Jassam et al. [54] | 2009 | UK | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000, GFC | 40 | 409 | 16 |

| 34 | Don-Wauchope et al. [55] | 2009 | South Africa | cross-sectional | All age | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 60 | 170 | 48 |

| 35 | Hattori et al. [9] | 2010 | Japan | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | EIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 292 | 44 |

| 36 | Anaforoglu et al. [56] | 2010 | Turkey | case-control | Adult | Female | No | CLIA | PEG 8000 | 40 | 34 | 14 |

| 37 | McCudden et al. [11] | 2010 | USA | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 120 | 20 |

| 38 | Gulcelik et al. [57] | 2010 | Turkey | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | CLIA | PEG | 40 | 174 | 76 |

| 39 | Taghipour et al. [58] | 2011 | Iran | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 188 | 32 |

| 40 | Can et al. [10] | 2011 | Turkey | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 84 | 31 |

| 41 | Morteza et al. [59] | 2011 | Iran | longitudinal | Adult | Both | hPRL due to hypothalamus or stalk compression | IRMA | PEG | 40 | 37 | 3 |

| 42 | Thirunavakkarasu et al. [60] | 2012 | India | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | Infertility | ECLIA | PEG | 40 | 183 | 21 |

| 43 | Sari et al. [61] | 2012 | Turkey | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | Type 2 diabetes | ECLIA | PEG 8000 | 40 | 40 | 13 |

| 44 | Isik et al. [62] | 2012 | Turkey | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 337 | 88 |

| 45 | Tamer et al. [63] | 2012 | Turkey | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | No | ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 161 | 60 |

| 46 | Chawla et al. [64] | 2012 | Ethiopia | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | No | ECLIA | PEG, GFC | 40 | 100 | 34 |

| 47 | Lu et al. [65] | 2012 | Taiwan | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | IRMA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 70 | 15 |

| 48 | Kim et al. [66] | 2013 | Korea | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | Major depression on SSRI | CLIA | PEG 8000 | 52.8 | 6 | 0 |

| 49 | Leaños-Miranda et al. [67] | 2013 | Mexico | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | Gynecological disorder | EIA | PEG 6000, GFC | - | 326 | 57 |

| 50 | Alpañés et al. [68] | 2013 | Spain | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 16 | 2 |

| 51 | Radavelli-Bagatini et al. [69] | 2013 | Brazil | longitudinal | Adult | Female | No | IRMA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 32 | 9 |

| 52 | Jamaluddin et al. [70] | 2013 | Malaysia | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000, GFC | 40 | 204 | 9 |

| 53 | Elenkova et al. [71] | 2013 | Bulgaria | case-control | Adult | Both | Prolactinoma | RIA | PEG 8000 | 40 | 131 | 10 |

| 54 | Whitehead et al. [72] | 2014 | Britain | cross-sectional | Unspecified | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | - | 175 | 26 |

| 55 | Hayashida et al. [73] | 2014 | Brazil | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | PCOS | FIA | PEG 6000 | 30 | 34 | 16 |

| 56 | Silva et al. [74] | 2014 | Portugal | cross-sectional | Unspecified | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 96 | 2 |

| 57 | Beda-Maluga et al. [75] | 2015 | Poland | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | CLIA | PEG, Ultrafiltration, GFC | 40 | 245 | 27 |

| 58 | Parlant-Pinet et al. [76] | 2015 | France | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | RIA, ECLIA | PEG 6000, GFC | 30 | 222 | 63 |

| 59 | Che Soh et al. [77] | 2016 | Malaysia | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG 8000 | 40 | 133 | 9 |

| 60 | Chen et al. [78] | 2016 | China | cross-sectional | All age | Both | No | CLIA, ECLIA | PEG 6000, GFC | 60 | 122 | 38 |

| 61 | Hattori et al. [79] | 2016 | Japan | cross-sectional | Adult | Female | No | EIA, CLIA | PEG 6000, GFC | 40 | 37 | 2 |

| 62 | Akbulut et al. [80] | 2017 | Turkey | cross-sectional | Unspecified | Both | No | CLIA, ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 376 | 19 |

| 63 | Soto-Pedre et al. [81] | 2017 | UK | longitudinal | Unspecified | Both | No | CLIA, ECLIA | unknown | - | 1301 | 97 |

| 64 | Dogansen et al. [82] | 2018 | Turkey | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | Prolactinomas | ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 66 | 0 |

| 65 | Kalsi et al. [83] | 2018 | India | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 25 | 102 | 22 |

| 66 | Barth et al. [84] | 2018 | UK | cross-sectional | Unspecified | Both | No | CLIA | PEG 6000 | 60 | 672 | 36 |

| 67 | Ayan et al. [85] | 2019 | Turkey | cross-sectional | Adult | Both | No | ECLIA | PEG 6000 | 40 | 73 | 10 |

n: Number of patients with, RIA: Radioimmunoassay, FIA: Fluoroimmunoassay, CLIA: Chemiluminescence Immunoassay, ECLIA: Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay, IRMA: Immunoradiometric Assay, IFMA: Immunofluorometric Assay, EIA: Enzyme Immunoassay, ELISA: Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay, PEG: Polyethylene glycol, GFC: Gel Filtration Chromatography, R: Recovery, SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus, PCOS: Polycystic ovarian syndrome, hPRL: hyperprolactinemia, mPRL: macroprolactinemia, UK: United Kingdom, USA: United States of America.

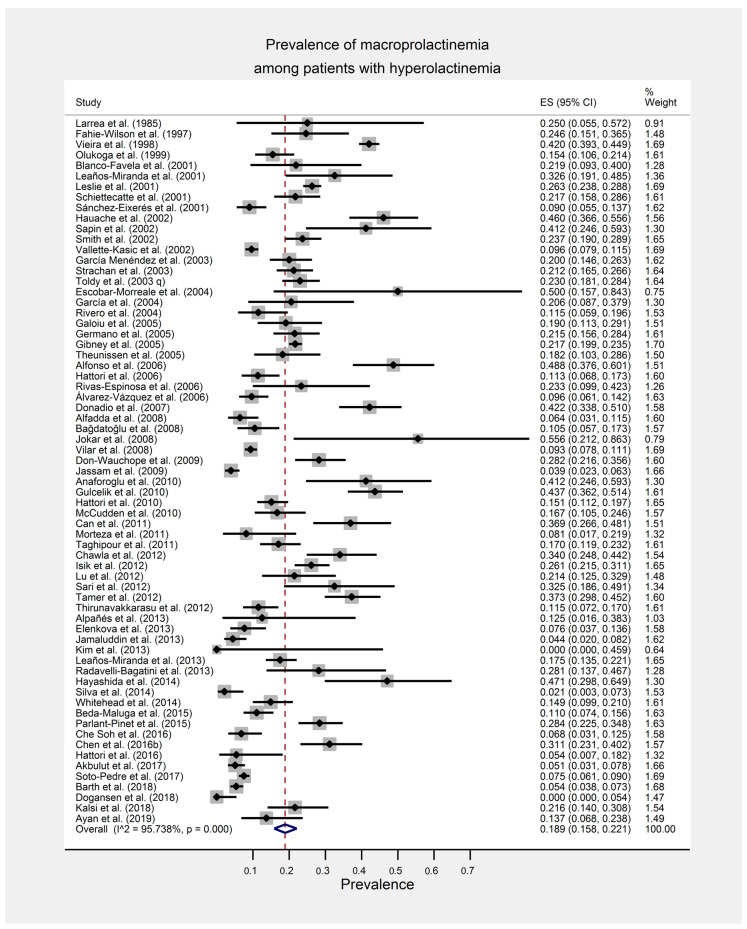

3.2. Prevalence of Macroprolactinemia among Patients with Hyperprolactinemia

Prevalence of mPRL among patients with hPRL from the included 67 studies ranged from 0.0% to 55.6% with a random effects pooled prevalence of 18.9% (95% CI: 15.8%, 22.1%) (Figure 2). There was a substantial statistical heterogeneity among the individual study estimates [χ2 (66) = 1548.67, p < 0.001, I2 = 95.7%].

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis for the global estimate of the prevalence of macroprolactinemia among patients with hyperprolactinemia.

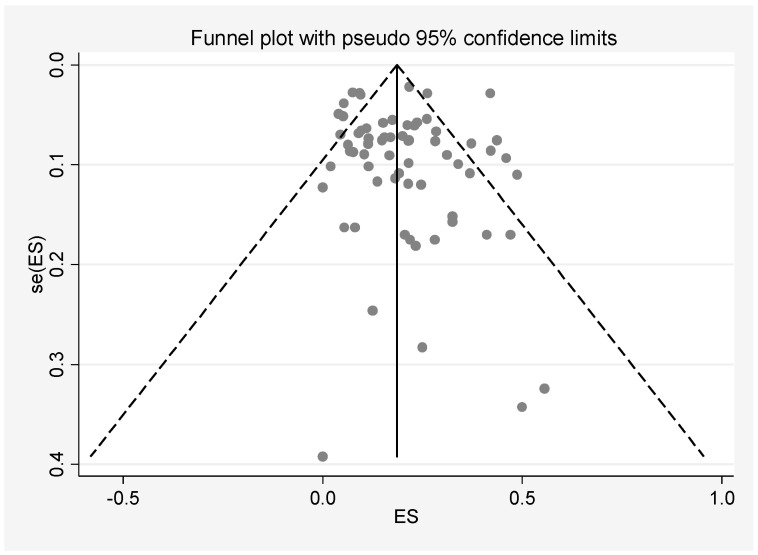

3.3. Quality Assessment and Publication Bias

Egger’s test for small-study effects indicates that there was no publication bias observed among all the included studies (β = 0.366; standard error of β = 0.418; 95% CI: −0.470, 1.201; t = 0.87, p = 0.385). The symmetry of the funnel plot agrees with the result of Egger’s test (Figure 3). A sensitivity analysis was conducted in which every study was removed in turn. The results showed no significant alterations in pooled prevalence and 95% CI values, indicating high stability of this meta-analysis (Supplementary Materials Table S1).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of publication bias. ES = Effect size estimate (prevalence).

3.4. Subgroup and Meta-Regression Analyses

Variation in the prevalence estimate according to study region was explored by grouping the studies according to the World Health Organization Member States regions (African Region, Region of the Americas, South-East Asia Region, European Region, Eastern Mediterranean Region, and Western Pacific Region). The highest random effects pooled prevalence was observed in the African region (30.3%), followed by Region of the Americas (29.1%), European (17.5%), Eastern Mediterranean (13.9%), South-East Asian (12.7%), and Western Pacific Region (12.6%).

Further exploration of the variation in the prevalence estimate was made according to sex, age groups, year period of publication, and the types of PEG used for the detection of macroprolactin (PEG 6000 vs. PEG 8000). The summary of estimates and heterogeneity are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of macroprolactinemia among patients with hyperprolactinemia.

| Study Characteristic | Number of Studies | Random Effect Pooled Prevalence | 95% CI of Pooled Prevalence | Within Group Heterogeneity | Between Group Heterogeneity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | χ2 (df) | p-Value | χ2 (df) | p-Value | ||||

| Region | ||||||||

| European Region | 37 | 17.5 | 14.0, 21.2 | 95.7 | 840.70 (36) | <0.001 | 7.32 (3) | 0.062 |

| Region of the Americas | 14 | 29.1 | 18.5, 41.0 | 97.1 | 455.07 (13) | <0.001 | ||

| Western Pacific Region | 7 | 12.6 | 6.7, 19.9 | 89.3 | 55.94 (6) | <0.001 | ||

| South-East Asian Region | 3 | 12.7 | 4.7, 23.1 | - | - | - | ||

| African Region | 2 | 30.3 | 25.0, 36.0 | - | - | - | ||

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 4 | 13.9 | 4.8, 26.3 | 83.8 | 18.53 (3) | <0.001 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Both (male and female) | 52 | 17.1 | 13.8, 20.6 | 96.2 | 1359.49 (51) | <0.001 | 6.56 (1) | 0.010 |

| Female only | 14 | 25.4 | 19.6, 31.6 | 84.9 | 86.49 (13) | <0.001 | ||

| Male only | 1 | 41.2 | 24.6, 59.3 | - | - | - | ||

| Age group | ||||||||

| Adults only | 48 | 19.8 | 16.6, 23.2 | 93.3 | 697.08 (47) | <0.001 | 0.23 (1) | 0.630 |

| Teenagers and adults | 10 | 18.0 | 11.9, 25.0 | 92.2 | 114.91 (9) | <0.001 | ||

| Teenagers only | 1 | 21.9 | 9.3, 40.0 | - | - | - | ||

| Year period | ||||||||

| Before 2000 | 4 | 26.5 | 11.2, 45.2 | 95.4 | 64.56 (3) | <0.001 | 2.64 (2) | 0.267 |

| Between 2000 and 2009 | 30 | 20.4 | 16.5, 24.5 | 94.6 | 536.29 (29) | <0.001 | ||

| Between 2010 and 2019 | 33 | 16.4 | 12.4, 20.9 | 94.3 | 557.34 (32) | <0.001 | ||

| PEG type | ||||||||

| PEG 6000 | 47 | 18.8 | 15.0, 23.0 | 95.6 | 1053.67 (46) | <0.001 | 0.06 (1) | 0.801 |

| PEG 8000 | 6 | 16.7 | 7.8, 27.7 | 90.6 | 53.43 (6) | <0.001 | ||

PEG: Polyethylene glycol.

For subgroup analysis of age group, eight studies were excluded because those studies did not specify the age group of their study participants. Age groups were classified as either involving adults only, teenagers only, or teenagers and adults. Year periods indicate the period of time when the study was published, categorized as either published before 2000, between 2000 and 2009, or between 2010 and 2019. For PEG type, the studies were categorized to either using PEG 6000 or PEG 8000. Studies that do not report the type of PEG used (n = 14) were excluded.

A statistically significant subgroup difference (interaction) was detected when the subgroup analysis was conducted according to sex (p = 0.010). A lower prevalence estimate was observed among studies involving both male and female participants as compared to studies involving only female participants (17.1% vs. 25.4%).

Meta-regression analysis reveals that the year of the studies had a significant influence on the prevalence where lower prevalence was observed in more recent studies (p = 0.010). No significant association was observed for sample size (p = 0.557) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Individual variable (univariable) meta-regression model for each study characteristic.

| Study Characteristic | Number of Studies | Regression Coefficient (β) | Standard Error of β | 95% CI of β | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 67 | −0.00002 | 0.00003 | −0.00008, 0.00004 | −0.59 | 0.557 |

| Year of the study | 67 | −0.007 | 0.003 | −0.012, −0.002 | −2.66 | 0.010 |

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis showed an estimated prevalence of mPRL among patients with hPRL of 18.9%. Variation in the prevalence estimate was observed when the subgroup analysis was conducted according to the region. In the Region of the Americas and African Region, the subgroup analysis indicates a higher prevalence of mPRL, whereas in the European, Western Pacific, South-East Asian, and Eastern Mediterranean Region, the prevalence is slightly lower. The interpretation of this subgroup analysis, however, needs to be made with caution due to the small number of studies from the Western Pacific (n = 7), South-East Asian (n = 3), African (n = 2), and Eastern Mediterranean Region (n = 4). One study in the Region of the Americas reported a prevalence of 46%, and this finding reflected selection bias of the study because of the specialized nature of the study center. This center received samples from other laboratories when the possible diagnosis of mPRL was raised [33].

In this current meta-analysis, we could not compare the prevalence estimate between males and females as only one study was conducted with male participants [34]. Comparing studies conducted with female participants only to studies conducted with male and female participants reveals a significant difference. A lower prevalence estimate was observed among studies involving both sexes than studies involving only female participants. Findings from previous studies regarding the matter are inconclusive, with some studies reporting no difference in the prevalence of mPRL between sex [77,86,87,88]. In contrast, some other studies reported a higher prevalence of mPRL among females than males [35,36,51,89]. This could be due to a higher number of female patients being investigated for infertility and menstrual disturbance than men who are only being investigated for sexual dysfunction [69,90].

Subgroup analysis also did not show any difference in prevalence estimate based on age group, similar to other previous studies [49,88]. However, several other studies reported that the prevalence of mPRL tends to increase with advancing age [36,86].

Subgroup analysis by year periods reveals a reduction in the prevalence of mPRL in recent studies. Further evaluation by meta-regression analysis supports the finding and indicates that a lower prevalence estimate was reported in more recent studies. In this meta-analysis, however, we did not find any possible explanation for this variation.

A comparison between the type of PEG that has been used in the precipitation of macroprolactin shows a lower prevalence in studies that used PEG 8000 compared to those that used PEG 6000. However, only six studies used PEG 8000 as compared to 47 studies that used PEG 6000. A previous study reported a significant constant bias between the two macroprolactin precipitation methods. Therefore, they suggest laboratories that use PEG 8000 should consider the transference of the reference interval established with PEG 6000 carefully [91].

Among all studies included in this review, we found that various cut-offs for PRL level have been used for the screening of hPRL and mPRL with different percentages of PRL recovery post-PEG for diagnosis of mPRL. Immunoassays were performed using various systems, such as the Architect, DELFIA, Cobas, Elecsys, and IMMULITE. Variability of the PRL level based on the different immunoassay measurement system has been previously reported [32,79]. Apart from that, heterogeneity in the mPRL screening method between studies was observed. Some authors used only one method for either screening with PEG/ultrafiltration/protein A separation/protein G separation or GFC alone, whereas others chose to combine screening plus confirmation with GFC.

Several limitations need to be noted in this meta-analysis. Significant heterogeneity was identified, even though random effect models were carried out. This limitation is observed in any other meta-analyses of epidemiological studies, in which the source of heterogeneity may result from unreported factors. In this meta-analysis, we decided that it is important to show whether statistically significant subgroup differences exist based on subgroup analysis, even though there is considerable heterogeneity within subgroups. Between-group comparison based on the subgroup analysis, therefore, needs to be made with caution, and we acknowledge the uncertainty in the evidence due to inconsistency between individual study results.

In this meta-analysis, we could not examine the heterogeneity effect of sex (comparison between male and female) as only one study reported the prevalence of mPRL specifically among male hPRL patients. Similarly, the influence of age on the prevalence estimate could not be examined since only one study involved only teenagers, and no study involved only the elderly. All included studies were not race-specific, rendering the variation to be examined. Not all included studies report the exact protocol for sample collection, which may influence the level of PRL such as physiological stress and diurnal variation (serum PRL levels are known to be higher in the afternoon than in the morning). Furthermore, other common conditions that cause variability of PRL levels such as fasting state, exercise, history of drug intake, prior chest wall surgery or trauma, and comorbidities were not reported.

5. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis examining the global prevalence of mPRL among patients with hPRL. The pool prevalence of mPRL was 18.9% among patients with hPRL, indicating that the finding of mPRL is common among patients with hPRL. With macroprolactin causing nearly one-fifth of hPRL cases, screening for mPRL should be made routine before an investigation of other causes of hPRL.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/21/8199/s1, Supplementary Table S1: “Leave-one-out” sensitivity analysis for the meta-analysis on the prevalence of macroprolactinemia among patients with hyperprolactinemia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.A.C.S., N.M.Y., J.O., A.M.J., N.S., T.S.T.I., W.N.W.A. and A.K.G.; Methodology, N.A.A.C.S., N.M.Y., J.O., A.M.J., N.S., T.S.T.I., W.N.W.A. and A.K.G.; Validation, N.A.A.C.S., N.M.Y. and J.O.; Formal analysis, N.M.Y. and A.K.G.; Data curation, N.A.A.C.S., N.M.Y. and J.O.; Writing—original draft preparation, N.A.A.C.S. and N.M.Y.; Writing—review and editing, N.A.A.C.S., N.M.Y., J.O., A.M.J., N.S., T.S.T.I., W.N.W.A. and A.K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Delitala G. Clinical Endocrinology. Blackwell Science Ltd.; London, UK: 1998. Hyperprolactinaemia: Causes, biochemical diagnosis and tests of prolactin secretion; pp. 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melmed S., Kleinberg D. Anterior pituitary. Williams Textb. Endocrinol. 2003;11:155–261. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasum M., Oreskovic S., Zec I., Jezek D., Tomic V., Gall V., Adzic G. Macroprolactinemia: New insights in hyperprolactinemia. Biochem. Med. 2012;22:171–179. doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasum M., Orešković S., Čehić E., Šunj M., Lila A., Ejubović E. Laboratory and clinical significance of macroprolactinemia in women with hyperprolactinemia. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;56:719–724. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hattori N., Ikekubo K., Nakaya Y., Kitagawa K., Inagaki C. Immunoglobulin G Subclasses and Prolactin (PRL) Isoforms in Macroprolactinemia Due to Anti-PRL Autoantibodies. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;90:3036–3044. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavanagh-Wright L., Smith T.P., Gibney J., McKenna T.J. Characterization of macroprolactin and assessment of markers of autoimmunity in macroprolactinaemic patients. Clin. Endocrinol. 2009;70:599–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaishya R., Gupta R., Arora S. Macroprolactin; A Frequent Cause of Misdiagnosed Hyperprolactinemia in Clinical Practice. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2010;11:161–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonhoff A., Vuille J.-C., Gomez F., Gellersen B. Identification of macroprolactin in a patient with asymptomatic hyperprolactinemia as a stable PRL-IgG complex. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 1995;103:252–255. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hattori N., Ishihara T., Saiki Y., Shimatsu A. Macroprolactinaemia in patients with hyperprolactinaemia: Composition of macroprolactin and stability during long-term follow-up. Clin. Endocrinol. 2010;73:792–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Can M., Guven B., Atmaca H., Acıkgoz S., Mungan G. Clinical characterization of patients with macroprolactinemia and monomeric hyperprolactinemia. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2011;27:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCudden C.R., Sharpless J.L., Grenache D.G. Comparison of multiple methods for identification of hyperprolactinemia in the presence of macroprolactin. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2010;411:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider W., Marcovitz S., Al-Shammari S., Yago S., Chevalier S. Reactivity of macroprolactin in common automated immunoassays. Clin. Biochem. 2001;34:469–473. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9120(01)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavaco B., Prazeres S., Santos M., Sobrinho L., Leite V. Hyperprolactinemia due to big big prolactin is differently detected by commercially available immunoassays. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 1999;22:203–208. doi: 10.1007/BF03343542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fahie-Wilson M.N. Detection of Macroprolactin Causing Hyperprolactinemia in Commercial Assays for Prolactin. Clin. Chem. 2000;46:2022–2023. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/46.12.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beltran L., Fahie-Wilson M.N., McKenna T.J., Kavanagh L., Smith T.P. Serum Total Prolactin and Monomeric Prolactin Reference Intervals Determined by Precipitation with Polyethylene Glycol: Evaluation and Validation on Common ImmunoAssay Platforms. Clin. Chem. 2008;54:1673–1681. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.105312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenna T.J. Should macroprolactin be measured in all hyperprolactinaemic sera? Clin. Endocrinol. 2009;71:466–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suliman A.M., Smith T.P., Gibney J., McKenna T.J. Frequent Misdiagnosis and Mismanagement of Hyperprolactinemic Patients before the Introduction of Macroprolactin Screening: Application of a New Strict Laboratory Definition of Macroprolactinemia. Clin. Chem. 2003;49:1504–1509. doi: 10.1373/49.9.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibney J., Smith T., McKenna T. The Impact on Clinical Practice of Routine Screening for Macroprolactin. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;90:3927–3932. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiettecatte J., De Schepper J., Velkeniers B., Smitz J., Van Steirteghem A. Rapid Detection of Macroprolactin in tHe Form of Prolactin-Immunoglobulin G Complexes by Immunoprecipitation with Anti-human IgG-Agarose. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2001;39:1244–1248. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2001.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prazeres S., Santos M.A., Ferreira H.G., Sobrinho L. A practical method for the detection of macroprolactinaemia using ultrafiltration. Clin. Endocrinol. 2003;58:686–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sapin R., Kertesz G. Macroprolactin Detection by Precipitation with Protein A-Sepharose: A Rapid Screening Method Compared with Polyethylene Glycol Precipitation. Clin. Chem. 2003;49:502–505. doi: 10.1373/49.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fahie-Wilson M., Halsall D. Polyethylene glycol precipitation: Proceed with care. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2008;45:233–235. doi: 10.1258/acb.2008.007262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoy D., Brooks P., Woolf A., Blyth F., March L., Bain C., Baker P., Smith E., Buchbinder R. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: Modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012;65:934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larrea F., Villanueva C., Cravioto M.C., Escorza A., Del Real O. Further evidence that big, big prolactin is preferentially secreted in women with hyperprolactinemia and normal ovarian function. Fertil. Steril. 1985;44:25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)48672-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fahie-Wilson M., Soule S. Macroprolactinaemia: Contribution to hyperprolactinaemia in a district general hospital and evaluation of a screening test based on precipitation with polyethylene glycol. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 1997;34:252–258. doi: 10.1177/000456329703400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vieira J.G.H., Tachibana T.T., Obara L.H., Maciel R.M. Extensive Experience and Validation of Polyethylene Glycol Precipitation as a Screening Method for Macroprolactinemia. Clin. Chem. 1998;44:1758–1759. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/44.8.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olukoga A., Kane J. Macroprolactinaemia: Validation and application of the polyethylene glycol precipitation test and clinical characterization of the condition. Clin. Endocrinol. 1999;51:119–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanco-Favela F., Quintal M.G., Chavez-Rueda A., Leanos-Miranda A., Berron-Peres R., Baca-Ruiz V., Lavalle-Montalvo C. Anti-prolactin autoantibodies in paediatric systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus. 2001;10:803–808. doi: 10.1177/096120330101001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leanos-Miranda A., Pascoe-Lira D., Chávez-Rueda K., Blanco-Favela F. Detection of macroprolactinemia with the polyethylene glycol precipitation test in systemic lupus erythematosus patients with hyperprolactinemia. Lupus. 2001;10:340–345. doi: 10.1191/096120301672772070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sánchez-Eixerés M.R., Mauri M., Alfayate R., Graells M.L., Miralles C., López A., Picó A. Prevalence of macroprolactin detected by Elecsys® 2010. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2001;56:87–92. doi: 10.1159/000048097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leslie H., Courtney C., Bell P., Hadden D., McCance D., Ellis P., Sheridan B., Atkinson A. Laboratory and clinical experience in 55 patients with macroprolactinemia identified by a simple polyethylene glycol precipitation method. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:2743–2746. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith T.P., Suliman A.M., Fahie-Wilson M.N., McKenna T.J. Gross Variability in the Detection of Prolactin in Sera Containing Big Big Prolactin (Macroprolactin) by Commercial Immunoassays. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87:5410–5415. doi: 10.1210/jc.2001-011943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hauache O.M., Rocha A.J., Maia A.C., Jr., Maciel R.M., Vieira J.G.H. Screening for macroprolactinaemia and pituitary imaging studies. Clin. Endocrinol. 2002;57:327–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sapin R., Gasser F., Grucker D. Free prolactin determinations in hyperprolactinemic men with suspicion of macroprolactinemia. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2002;316:33–41. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(01)00733-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vallette-Kasic S., Morange-Ramos I., Selim A., Gunz G., Morange S., Enjalbert A., Martin P.-M., Jaquet P., Brue T. Macroprolactinemia revisited: A study on 106 patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87:581–588. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toldy E., Löcsei Z., Szabolcs I., Góth M.I., Kneffel P., Szöke D., Kovács G.L. Macroprolactinemia. Endocrine. 2003;22:267–273. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:22:3:267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strachan M.W., Teoh W.L., Don-Wauchope A.C., Seth J., Stoddart M., Beckett G.J. Clinical and radiological features of patients with macroprolactinaemia. Clin. Endocrinol. 2003;59:339–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.García L.M., Díez A.H., de los Ríos Ciriza C., Delgado M.G., Orejas A.G., Fernández A.E., González C.M., Fernández M.F. Macroprolactin as etiology of hyperprolactinemia. Method for detection and clinical characterization of the entity in 39 patients. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2003;203:459–464. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2565(03)71328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia M., Colombani-Vidal M., Zylbersztein C., Testi A., Marcos J., Arturi A., Babini J., Scaglia H. Analysis of molecular heterogeneity of prolactin in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2004;13:575–583. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu1068oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Escobar-Morreale H.F. Macroprolactinemia in women presenting with hyperandrogenic symptoms: Implications for the management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2004;82:1697–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rivero A., Alonso E., Grijalba A. Decision cut-off of the polyethylene glycol precipitation technique in screening for macroprolactinemia on Immulite 2000. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2004;42:566–568. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2004.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galoiu S., Kertesz G., Somma C., Coculescu M., Brue T. Clinical espression of big-big prolactin and influence of macroprolactinemia upon immunodiagnostic tests. Acta Endocrinol. (1841-0987) 2005;1:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Germano L., Mormile A., Filtri L., Cocciardi E., Di Grazia M., Marranca D., Limone P., Migliardi M. Evaluation of polyethylene glycol precipitation as screening test for macroprolactinemia using Architect immunoanalyser. Immuno-Anal. Biol. Spécialisée. 2005;20:402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.immbio.2005.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Theunissen C., De Schepper J., Schiettecatte J., Verdood P., Hooghe-Peeters E., Velkeniers B. Macroprolactinemia: Clinical Significance and Characterization of the Condition. Acta Clin. Belg. 2005;60:190–197. doi: 10.1179/acb.2005.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hattori N., Nakayama Y., Kitagawa K., Ishihara T., Saiki Y., Inagaki C. Anti-prolactin (PRL) autoantibody-binding sites (epitopes) on PRL molecule in macroprolactinemia. J. Endocrinol. 2006;190:287–293. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alfonso A., Rieniets K.I., Vigersky R.A. Incidence and Clinical Significance of Elevated Macroprolactin Levels in Patients with Hyperprolactinemia. Endocr. Pract. 2006;12:275–280. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Álvarez-Vázquez P., Pérez D.R., García E.A., Fernández C.P., Abad E.H., Olivié M.A.A. Significación clínica de la macroprolactina. Endocrinol. Nutr. 2006;53:374–378. doi: 10.1016/S1575-0922(06)71117-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rivas-Espinosa J., Trigos-Landa Á., Bocanegra-García V., Acosta-González R.I., Bocanegra-Alonso A., Rivera-Sánchez G. Estimación de macroprolactina después de precipitación con polietilenglicol en dos inmunoensayos comerciales. Bioquimia. 2006;31:140–145. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donadio F., Barbieri A., Angioni R., Mantovani G., Beck-Peccoz P., Spada A., Lania A.G. Patients with macroprolactinaemia: Clinical and radiological features. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2007;37:552–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jokar M., Maybodi N.T., Amini A., Fard M.H. Prolactin and macroprolactin in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2008;11:257–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2008.00378.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polat G., Dolgun H., Karatafi M.A. The importance of macroprolactinemia in the differential diagnosis of hyperprolactinemic patients. Turk. Neurosurg. 2008;18:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vilar L., Freitas M., Naves L., Casulari L., Azevedo M., Montenegro R., Barros A., Faria M., Nascimento G., Lima J., et al. Diagnosis and management of hyperprolactinemia: Results of a Brazilian multicenter study with 1234 patients. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2008;31:436–444. doi: 10.1007/BF03346388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alfadda A. Macroprolactin as a Cause of Hyperprolactinemia: Clinical and Radiological Features. Turk. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;12:46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jassam N., Paterson A., Lippiatt C., Barth J. Macroprolactin on the Advia Centaur: Experience with 409 patients over a three-year period. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2009;46:501–504. doi: 10.1258/acb.2009.009059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Don-Wauchope A.C., Hoffmann M., Le Riche M., Ascott-Evans B.H. Review of the prevalence of macroprolactinaemia in a South African hospital. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2009;47:882–884. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2009.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anaforoglu I., Ertorer M.E., Kozanoglu I., Unal B., Haydardedeoglu F.E., Bakiner O., Bozkirli E., Tutuncu N.B., Demirag N.G. Macroprolactinemia, like hyperprolactinemia, may promote platelet activation. Endocrine. 2010;37:294–300. doi: 10.1007/s12020-009-9304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gulcelik N.E., Usman A. Macroprolactinaemia in diabetic patients. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2010;31:270–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taghipour H., Esmaili H.A. Detection of macroprolactinemia in hyperprolactinemic patients by PEG precipitation using Elecsys 2010 immunoanalyser. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2011;27:430–433. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morteza T., Samira Z. Macroprolactinemia in Patients Presenting with Stalk Compressing Masses. Neurosurg. Q. 2011;21:42–43. doi: 10.1097/WNQ.0b013e3182059338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thirunavakkarasu K., Dutta P., Sridhar S., Dhaliwal L., Prashad G.R.V., Gainder S., Sachdeva N., Bhansali A. Macroprolactinemia in hyperprolactinemic infertile women. Endocrine. 2013;44:750–755. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-9925-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sari F., Sari R., Ozdem S., Sarikaya M., Cetinkaya R. Serum prolactin and macroprolactin levels in diabetic nephropathy. Clin. Nephrol. 2012;78:33–39. doi: 10.5414/CN107061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Isik S., Berker D., Tutuncu Y.A., Ozuguz U., Gokay F., Erden G., Ozcan H.N., Kucukler F.K., Aydin Y., Guler S. Clinical and radiological findings in macroprolactinemia. Endocrine. 2012;41:327–333. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tamer G., Telci A., Mert M., Uzum A.K., Aral F., Tanakol R., Yarman S., Boztepe H., Colak N., Alagöl F. Prevalence of pituitary adenomas in macroprolactinemic patients may be higher than it is presumed. Endocrine. 2012;41:138–143. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9536-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chawla R., Antonios T., Berhanu E., Ayana G. Detection of Macroprolactinemia and Molecular Characterization of Prolactin Isoforms in Blood Samples of Hyperprolactinemic Women. J. Med. Biochem. 2012;31:19–26. doi: 10.2478/v10011-011-0038-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu C.-C., Hsieh C.-J. The importance of measuring macroprolactin in the differential diagnosis of hyperprolactinemic patients. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2012;28:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2011.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim S., Park Y.-M. Serum Prolactin and Macroprolactin Levels among Outpatients with Major Depressive Disorder Following the Administration of Selective Serotonin-Reuptake Inhibitors: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e82749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leaños-Miranda A., Ramírez-Valenzuela K.L., Campos-Galicia I., Chang-Verdugo R., Chinolla-Arellano L.Z. Frequency of Macroprolactinemia in Hyperprolactinemic Women Presenting with Menstrual Irregularities, Galactorrhea, and/or Infertility: Etiology and Clinical Manifestations. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013;2013:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2013/478282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alpañés M., Sanchón R., Martínez-García M.Á., Martínez-Bermejo E., Escobar-Morreale H.F. Prevalence of hyperprolactinaemia in female premenopausal blood donors. Clin. Endocrinol. 2013;79:545–549. doi: 10.1111/cen.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Radavelli-Bagatini S., Lhullier F., Mallmann E.S., Spritzer P.M. Macroprolactinemia in women with hyperprolactinemia: A 10-year follow-up. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2013;34:207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jamaluddin F.A., Sthaneshwar P., Hussein Z., Othman N., Peng C.S. Importance of screening for macroprolactin in all hyperprolactinaemic sera. Malays. J. Pathol. 2013;35:59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Elenkova A., Genov N., Abadzhieva Z., Kirilov G., Vasilev V., Kalinov K., Zacharieva S. Macroprolactinemia in Patients with Prolactinomas: Prevalence and Clinical Significance. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2013;121:201–205. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1333232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whitehead S., Cornes M., Ford C., Gama R. Reference ranges for serum total and monomeric prolactin for the current generation Abbott Architect assay. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2015;52:61–66. doi: 10.1177/0004563214547779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hayashida S.A., Marcondes J.A., Soares J.M., Jr., Rocha M.P., Barcellos C.R., Kobayashi N.K., Baracat E.C., Maciel G.A. Evaluation of macroprolactinemia in 259 women under investigation for polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Endocrinol. 2014;80:616–618. doi: 10.1111/cen.12266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silva A.M., Da Costa P.M., Pacheco A., Oliveira J.C., Freitas C. Assessment of macroprolactinemia by polyethylene glycol precipitation method. Rev. Port. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2014;9:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.rpedm.2014.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beda-Maluga K., Pisarek H., Romanowska I., Komorowski J., Świętosławski J., Winczyk K. Ultrafiltration—An alternative method to polyethylene glycol precipitation for macroprolactin detection. Arch. Med. Sci. 2015;11:1001. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.54854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parlant-Pinet L., Harthé C., Roucher F., Morel Y., Borson-Chazot F., Raverot G., Raverot V. Macroprolactinaemia: A biological diagnostic strategy from the study of 222 patients. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015;172:687–695. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Soh N.A.C., Omar J., Mohamed W.M.W., Abdullah M.R., Yaacob N.M. Low prevalence of macroprolactinaemia among patients with hyperprolactinaemia screened using polyethylene glycol 8000. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2016;11:464–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2016.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen Y., Song G., Wang Z. A new criteria for screening macroprolactinemia using polyethylene glycol treatment combined with different assays for prolactin. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016;20:1788–1794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hattori N., Aisaka K., Shimatsu A. A possible cause of the variable detectability of macroprolactin by different immunoassay systems. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2016;54:603–608. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2015-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Akbulut E.D., Ercan M., Erdoğan S., Topçuoğlu C., Yılmaz F.M., Turhan T. Assessment of macroprolactinemia rate in a training and research hospital from Turkey. Turk. J. Biochem. 2017;42:87–91. doi: 10.1515/tjb-2016-0156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Soto-Pedre E., Newey P.J., Bevan J.S., Greig N., Leese G.P. The epidemiology of hyperprolactinaemia over 20 years in the Tayside region of Scotland: The Prolactin Epidemiology, Audit and Research Study (PROLEARS) Clin. Endocrinol. 2017;86:60–67. doi: 10.1111/cen.13156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dogansen S.C., Yalin G.Y., Yarman S. Assessment of macroprolactinemia inpatients with prolactinoma. Turk. J. Biochem. 2017;43:71–75. doi: 10.1515/tjb-2017-0062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kalsi A.K., Halder A., Jain M., Chaturvedi P., Sharma J. Prevalence and reproductive manifestations of macroprolactinemia. Endocrine. 2019;63:332–340. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barth J.H., Lippiatt C.M., Gibbons S.G., Desborough R.A. Observational studies on macroprolactin in a routine clinical laboratory. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2018;56:1259–1262. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2018-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ayan N.N., Temeloglu E.K. An approach to screening for macroprolactinemia in all hyperprolactinemic sera. Int. J. Med. Biochem. 2019;2:19–23. doi: 10.14744/ijmb.2018.66375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hattori N., Ishihara T., Saiki Y. Macroprolactinaemia: Prevalence and aetiologies in a large group of hospital workers. Clin. Endocrinol. 2009;71:702–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shimatsu A., Hattori N. Macroprolactinemia: Diagnostic, Clinical, and Pathogenic Significance. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012;2012:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/167132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Muhtaroglu S., Keti D.B., Hacıoglu A. Macroprolactin: An overlooked reason of hyperprolactinemia. J. Lab. Med. 2019;43:163–168. doi: 10.1515/labmed-2019-0046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vassilatou E., Schinochoritis P., Marioli S., Tzavara I. Macroprolactinemia in a young man and review of the literature. Hormones. 2003;2:130–134. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sadideen H., Swaminathan R. Macroprolactin: What is it and what is its importance? Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2006;60:457–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Veljkovic K., Servedio D., Don-Wauchope A.C. Reporting of post-polyethylene glycol prolactin: Precipitation by polyethylene glycol 6000 or polyethylene glycol 8000 will change reference intervals for monomeric prolactin. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2012;49:402–404. doi: 10.1258/acb.2011.011238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.