Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus is an increasingly prevalent condition among heart failure (HF) patients. The long-term morbidity and mortality among patients with and without diabetes with HF with reduced (HFrEF), borderline (HFbEF), and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are not well described.

Methods

Using the Get With The Guidelines (GWTG)–HF Registry linked to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services claims data, we evaluated differences between HF patients with and without diabetes. Adjusted Cox proportional-hazard models controlling for patient and hospital characteristics were used to evaluate mortality and readmission outcomes.

Results

A cohort of 86,659 HF patients aged ≥65 years was followed for 3 years from discharge. Unadjusted all-cause mortality was between 4.4% and 5.5% and all-cause hospitalization was between 19.4% and 22.6% for all groups at 30 days. For all-cause mortality at 3 years from hospital discharge, diabetes was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.27 (95% CI 1.07–1.49, P = .0051) for HFrEF, 0.95 (95% CI 0.55–1.65, P = .8536) for HFbEF, 1.02 (95% CI 0.87–1.19, P = .8551) for HFpEF. For all-cause readmission, diabetes was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.06 (95% CI 0.87–1.29, P = .5585) for HFrEF, 1.48 (95% CI 1.15–1.90, P = .0023) for HFbEF, and 1.06 (95% CI 0.91–1.22, P = .4747) for HFpEF.

Conclusions

HFrEF and HFbEF patients with diabetes are at increased risk for mortality and rehospitalization after hospitalization for HF, independent of other patient and hospital characteristics. Among HFpEF patients, diabetes does not appear to be independently associated with significant additional risks.

The increasing burden of noncommunicable diseases has led to an epidemic of heart failure (HF) and diabetes mellitus globally.1–4 The prevalence of comorbid diabetes among hospitalized HF patients has increased and now exceeds 40%.5–7 The term diabetic cardiomyopathy has been suggested for HF without evidence of epicardial disease or long-standing hypertension.8 When both conditions coexist, the optimal strategies to improve health status, resource utilization, and outcomes are an area of active discovery. Diabetes and HF require frequent monitoring, significant lifestyle modifications, and multiple classes of medications for patients and physicians to navigate.

Among patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, the presence of comorbid diabetes increases the risk of adverse events and incident HF.9 How diabetes may interact with treatment strategies and contribute to additional long-term risks for HF patients is not well characterized in clinical practice. Understanding the interactions between these 2 common comorbidities in the clinical practice setting is critical for tailoring both acute and chronic management to achieve patient-centered goals. In addition, diabetes may influence morbidity and mortality risk among patients with HF with reduced (HFrEF), borderline (HFbEF), and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) differently, yet this has not been well studied.

The purpose of this analysis was to understand the long-term outcomes for patients with HF with and without diabetes, further stratified by ejection fraction. Using the Get With The Guidelines (GWTG)–HF Registry linked to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) claims data, we evaluated clinical differences and outcomes between patients with and without diabetes and a primary discharge diagnosis of HFrEF, HFbEF, or HFpEF.

Methods

Study cohort

The study cohort was obtained from GWTG-HF, a national prospective HF registry and quality improvement program sponsored by the American Heart Association (AHA). Details of the design and conduct of the GWTG-HF registry have been previously described.10,11 Patients discharged between January 1, 2006, and November 30, 2014, were screened for inclusion. All patients included in the GWTG-HF registry have been identified by physicians based on clinically diagnosed HF admission. Inclusion into the cohort required CMS claims linkage. Patients were excluded if they were not using fee-for-service Medicare at the month of index discharge, died during index hospitalization, were comfort care only, left against medical advice, were discharged to a short-term hospital, were discharged to hospice, or were missing left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) or medical history data.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes of interest were all-cause mortality and readmissions at 3 years after index discharge. Mortality was ascertained using CMS denominator file. Secondary outcomes of interest included cardiovascular readmission and major cardiovascular composite events defined by all-cause mortality or cardiovascular readmission. Cardiovascular readmissions included primary discharge diagnosis HF, acute coronary syndromes, ischemic stroke, and hemorrhagic stroke (Table I in the Supplementary Data).

Covariates

HF subtypes were defined by LVEF quantitative assessment criteria consistent with society guideline definitions: HFrEF, ≤40%; HFbEF, N40% and b50%; and HFpEF, ≥50%.12,13 Demographics included age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Abstracted medical histories from GWTG-HF include anemia, atrial arrhythmia, ventricular arrhythmia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal insufficiency, coronary artery disease/ischemic heart disease, depression, diabetes mellitus, ischemic history, smoking history, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and peripheral vascular disease. A new diagnosis of diabetes was based on patients without past medical history of diabetes that was newly diagnosed during the index HF hospitalization. Clinical measurements included admission and discharge vital signs, routine laboratory test results, and discharge medication lists. Hospital factors included bed size, teaching status, region, and rural/urban location.

Statistical analysis

Baseline patient and hospital characteristics were described by diabetes status and stratified by HF subtype: HFrEF, HFbEF, and HFpEF. Percentages, means with SDs, and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) were reported for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Standardized differences for characteristics between patients with and without diabetes were estimated.

Kaplan-Meier estimates were made for 3-year all-cause readmission and mortality end points. A Cox proportional-hazard model was used for the primary and secondary outcomes. Cox proportional models were adjusted for baseline patient and hospital characteristics. Control variables were selected based on a literature review and prior established models used in GWTG-HF.14–16 Random effects were used to adjust for clustering at the hospital level. Lack-of-fit tests were used to evaluate continuous covariates. Splines were used for select variables with nonlinear relationships on the hazards of interest. Multiple imputation was used for missing variables other than medical history and hospital characteristics. Variables with N35% missing were excluded from the models. Interactions were tested between diabetes status and select patient characteristics for the primary outcomes. Statistical significance was defined for values equal to or less than P = .05. Analyses were performed in SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Research support

This project was supported by the American Heart Association’s GWTG program and the American College of Cardiology Presidential Career Development award. No person or organization outside of the authors contributed in any substantive way to writing, editing, or statistical analyses reported in this manuscript.

Results

The final cohort included 89,659 patients from 417 sites (Table II in the Supplementary Data). An additional cohort to evaluate competing risk for 30-day end points secondary to inpatient mortality was defined with prespecified exclusions after day of admission (Table III in the Supplementary Data). Inpatient rates of mortality were lower among diabetic patients across HF categories and did not influence 30-day event reporting (Table IV in the Supplementary Data). The most common subtype of HF discharged was HFpEF (48.2%) followed by HFrEF (42.2%) and HFbEF (9.6%), and 39.9% had prevalent or incident comorbid diabetes (Table V, A and V, B in the Supplementary Data). Across all HF subtypes, patients with diabetes were a few years younger on average and had more ischemic heart disease, prior strokes, hypertension, and renal insufficiency (Table I). There were key differences by sex: patients with HFrEF were predominately male (59.4%), patients with HFbEF were sex balanced (female 49.7%), and patients with HFpEF were predominately female (66.2%). Patients with diabetes were more likely to receive statin therapy. Standardized differences for baseline characteristics are provided (Table VI in the Supplementary Data)

Table I.

Patient, hospital, and regional characteristics by diabetes status stratified by patients with HFrEF, HFbEF, and HFpEF

| HFrEF: ≤40%, | HFbEF: >40% & <50% | HFpEF: ≥50%. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes (n = 14,983) | No diabetes (n = 22,856) | Diabetes (n = 3601) | No diabetes (n = 5005) | Diabetes (n = 17,187) | No diabetes (n = 26,027) | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | 76.9 (7.7) | 80.1 (8.2) | 78.0 (7.8) | 82.2 (8.1) | 78.3 (7.9) | 83.0 (8.0 |

| Female | 39.6 | 41.2 | 47.3 | 51.5 | 63.8 | 67.9 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 74.6 | 80.8 | 77.7 | 83.1 | 75.0 | 84.8 |

| Black | 13.1 | 10.4 | 11.1 | 8.2 | 13.1 | 6.7 |

| Hispanic (any race) | 6.5 | 3.6 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| Asian | 4.0 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 3.7 |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Anemia | 19.3 | 14.6 | 23.8 | 18.7 | 25.8 | 20.0 |

| Smoking | 10.1 | 11.3 | 8.9 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 7.0 |

| Coronary disease | 65.0 | 54.4 | 64.1 | 52.1 | 50.8 | 40.7 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 35.8 | 39.1 | 39.6 | 47.6 | 37.9 | 47.3 |

| COPD or asthma | 28.3 | 25.7 | 31.4 | 27.0 | 34.2 | 29.7 |

| CVA/TIA | 17.8 | 14.3 | 18.4 | 14.6 | 18.4 | 15.8 |

| Previous MI | 29.5 | 24.1 | 25.2 | 18.5 | 15.5 | 11.7 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 17.5 | 11.1 | 17.5 | 12.5 | 15.6 | 10.7 |

| Prior heart failure | 69.2 | 64.6 | 65.8 | 60.6 | 61.3 | 56.2 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 60.2 | 46.0 | 60.7 | 46.6 | 59.3 | 43.. 4 |

| Hypertension | 81.2 | 70.1 | 85.0 | 75.6 | 86.5 | 78.5 |

| Renal insufficiency (SCr >2) | 25.3 | 17.1 | 27.3 | 16.9 | 27.1 | 15.7 |

| Dialysis | 3.8 | 1.8 | 4.9 | 2.4 | 4.7 | 2.4 |

| Ischemic history | 73.2 | 62.1 | 71.0 | 58.7 | 56.1 | 45.3 |

| Vital signs at admission | ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 137.6 (27.7) | 135.2 (27.0) | 147.4 (29.2) | 143.6 (28.5) | 150.3 (30.0) | 145.7 (29.5) |

| Heart rate (beat/min) | 85.1 (19.4) | 86.0 (20.4) | 83.5 (19.8) | 84.7 (20.4) | 80.2 (18.5) | 81.7 (19.7) |

| Laboratory tests at admission | ||||||

| Ejection fraction (%) (median, IQR) | 30 (21–35) | 28 (20–35) | 45 (44–45) | 45 (44–45) | 59 (55–63) | 60 (55–64) |

| HbA1C (%) | 7.2 (1.5) | 6.1 (0.9) | 7.2 (1.4) | 6.2 (0.9) | 7.0 (1.4) | 6.0 (0.9) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) (median, IQR) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) |

| BNP (pg/mL) (median, IQR) | 1012 (513–1881) | 1170 (606–2198) | 715 (381–1375) | 804 (440–1455) | 510 (261–937) | 578 (316–1059) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.1 (6.1) | 12.4 (4.2) | 11.8 (6.5) | 11.9 (3.3) | 11.3 (3.9) | 11.8 (4.7) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 134.1 (41.9) | 140.6 (40.5) | 138.0 (42.7) | 140.8 (40.1) | 137.2 (41.9) | 143.7 (41.1) |

| Procedures | ||||||

| Cardiac catheterization | 12.6 | 11.5 | 9.0 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 4.6 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2.4 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 1.6 |

| Dialysis | 3.3 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 1.9 | 4.2 | 2.1 |

| Vital signs at discharge | ||||||

| Weight change (kg) | −2.8 (8.4) | −2.5 (8.4) | −3.0 (9.2) | −2.6 (8.4) | −2.4 (9.3) | −2.3 (8.0) |

| BMI | 28.8 (6.9) | 25.4 (5.8) | 30.4 (7.7) | 26.5 (6.5) | 32.1 (8.5) | 27.2 (7.2) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 121.3 (19.5) | 118.1 (19.1) | 128.1 (20.0) | 123.7 (19.8) | 131.6 (20.7) | 126.5 (20.4) |

| Medications at discharge | ||||||

| ACE/ARB | 67.4 | 68.2 | 58.9 | 55.7 | 53.7 | 47.8 |

| ASA | 53.9 | 50.6 | 50.3 | 45.6 | 45.7 | 41.2 |

| β-Blocker | 88.7 | 86.9 | 83.8 | 79.9 | 76.0 | 71.1 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 23.3 | 23.3 | 12.9 | 11.8 | 9.3 | 9.1 |

| Statins | 46.4 | 37.2 | 44.6 | 33.9 | 42.7 | 30.8 |

| Hydralazine nitrate | 15.5 | 10.2 | 13.9 | 9.6 | 14.8 | 8.5 |

| Loop diuretic | 56.9 | 54.1 | 54.6 | 50.9 | 52.5 | 50.0 |

| Digoxin | 16.2 | 16.3 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 7.0 | 8.9 |

| Anticoagulation therapy | 33.9 | 35.1 | 34.2 | 37.5 | 31.3 | 35.5 |

| Clopidogrel prescribed | 19.4 | 14.0 | 19.0 | 12.5 | 14.4 | 9.7 |

| Discharge status | ||||||

| Length of stay (median, IQR) | 4.0 (3.0–7.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) |

| Discharge home | 77.6 | 77.4 | 75.1 | 73.5 | 70.7 | 69.5 |

| Hospital characteristics | ||||||

| Hospital type (teaching) | 73.3 | 72.5 | 70.9 | 70.0 | 72.0 | 70.3 |

| Number of beds | 413.5 (222.2) | 406.6 (210.7) | 400.1 (215.2) | 392.9 (205.3) | 399.1 (216.4) | 379.7 (202.0 |

| Rural location (versus urban) | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.9 |

| Region | ||||||

| West | 10.2 | 11.4 | 10.3 | 11.2 | 9.7 | 11.1 |

| South | 33.4 | 32.9 | 33.6 | 29.8 | 31.8 | 30.5 |

| Midwest | 26.0 | 24.2 | 25.9 | 25.6 | 26.8 | 24.0 |

| Northeast | 30.4 | 31.5 | 30.2 | 33.3 | 31.7 | 34.4 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; TIA, transient ischemic attack; MI, myocardial infarction; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; ACE, angiotension-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotension II receptor blocker; ASA, aspirin.

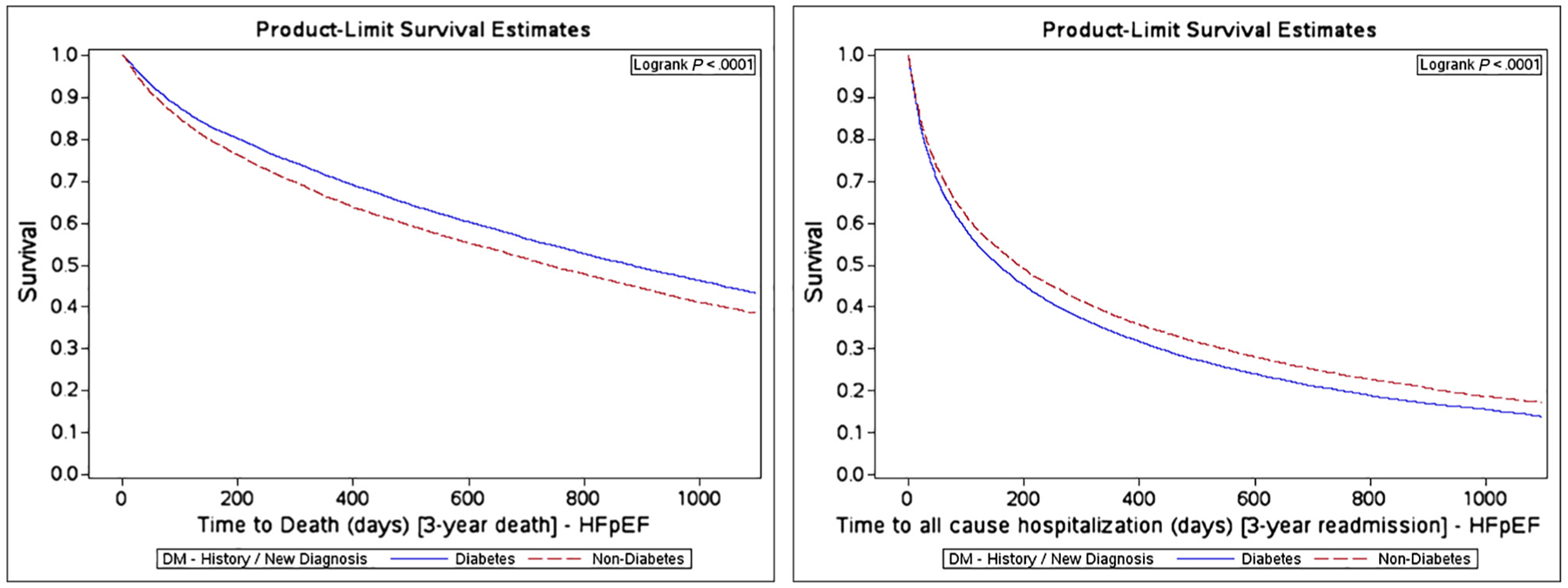

Unadjusted all-cause mortality rates at 30 days post-discharge were between 4.4% and 5.8% (Table II and Figures 1, 2, and 3). Readmission rates at 30 days were around 22% for patients with diabetes and 20% for patients without diabetes. Among patients with HFrEF, diabetes conferred a 27% (95% CI 7%−49%, P = .0051) greater adjusted hazard of all-cause mortality and 22% greater hazard for major adverse cardiac event (95% CI 7%−39%, P = .0024) compared with patients with no diabetes at 3 years of observation (Table III). Among HFbEF patients, diabetes did not seem to contribute an additional mortality risk; however, the all-cause readmission hazard was 48% (95% CI 15%−90%, P = .0023) greater for patients with diabetes, and cardiovascular readmission was 59% greater (95% CI 18%−116%, P = .0026) (See Table III and Figure 2). Among HFpEF patients, diabetes status was not associated with greater mortality or readmission risk that was statistically significant. (See Table III and Figure 3).

Table II.

Unadjusted event rates after discharge at 30 days, 1 year, and 3 years for HFrEF by diabetes status

| Event | Follow-up time | Diabetes | No diabetes | Diabetes | No diabetes | Diabetes | No diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFrEF: ≤40% | HFbEF: >40% & <50% | HFpEF: ≥50%. | |||||

| All-cause mortality | 30 d | 5.5% | 5.6% | 4.4% | 5.1% | 4.4% | 5.8% |

| 1 y | 34.7% | 33.5% | 31.2% | 33.7% | 29.1% | 34.2% | |

| 3 y | 62.7% | 59.0% | 62.0% | 61.1% | 56.6% | 61.4% | |

| All-cause readmissions | 30 d | 22.6% | 19.4% | 22.3% | 19.7% | 21.7% | 19.5% |

| 1 y | 63.8% | 57.0% | 65.2% | 59.1% | 64.0% | 59.0% | |

| 3 y | 78.6% | 73.1% | 80.6% | 76.1% | 80.5% | 75.0% | |

| CV readmissions | 30 d | 13.2% | 11.5% | 11.0% | 10.2% | 10.1% | 9.2% |

| 1 y | 43.6% | 38.2% | 42.2% | 36.3% | 36.9% | 33.5% | |

| 3 y | 57.3% | 51.3% | 56.2% | 50.3% | 51.9% | 46.3% | |

| MACE | 30 d | 17.1% | 15.6% | 14.4% | 14.2% | 13.5% | 13.9% |

| 1 y | 60.6% | 55.8% | 58.1% | 55.3% | 53.5% | 53.8% | |

| 3 y | 82.0% | 77.6% | 81.9% | 78.7% | 77.9% | 77.9% | |

CV, cardiovascular; MACE, major adverse cardiac events (composite of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular readmission).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for HFrEF for all-cause mortality and all-cause readmission by diabetes status.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for HFbEF for all-cause mortality and all-cause readmission by diabetes status.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for HFpEF for all-cause mortality and all-cause readmission by diabetes status.

Table III.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for diabetic patients compared with nondiabetic patients on 3-year outcomes stratified by HF subtype

| Unadjusted HR | P value | Adjusted HR* | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFrEF | ||||

| All-cause mortality | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) | <.0001 | 1.27 (1.07–1.49) | .0051 |

| All-cause readmission | 1.18 (1.15–1.21) | <.0001 | 1.06 (0.87–1.29) | .5585 |

| CV readmission | 1.17 (1.14–1.21) | <.0001 | 1.20 (0.95–1.51) | .1300 |

| MACE | 1.14 (1.11–1.17) | <.0001 | 1.22 (1.07–1.39) | .0024 |

| HFbEF | ||||

| All-cause mortality | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | .5092 | 0.95 (0.55–1.65) | .8536 |

| All-cause readmission | 1.16 (1.10–1.22) | <.0001 | 1.48 (1.15–1.90) | .0023 |

| CV readmission | 1.19 (1.12–1.28) | <.0001 | 1.59 (1.18–2.16) | .0026 |

| MACE | 1.09 (1.04–1.14) | .0007 | 1.54 (1.03–2.29) | .0360 |

| HFpEF | ||||

| All-cause mortality | 0.86 (0.84–0.88) | <.0001 | 1.02 (0.87–1.19) | .8551 |

| All-cause readmission | 1.15 (1.13–1.18) | <.0001 | 1.06 (0.91–1.22) | .4747 |

| CV readmission | 1.15 (1.12–1.19) | <.0001 | 1.16 (0.98–1.37) | .0815 |

| MACE | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | .6147 | 1.00 (0.88–1.13) | .9972 |

Adjusted patient and hospital characteristics as listed in the “Methods” section.

Interactions between diabetes and additional patient characteristics were tested. Among patients with HFrEF, women had a higher risk for mortality relative to men (P for interaction = .0195) (Table IVA). Additionally, white and Asian patients had worse outcomes with diabetes relative to African Americans and Hispanics (P for interaction = .0031). For patients with HFpEF, diabetes was a greater risk factor among those younger than 75 years (P for interaction = .0270).

Table IVA.

Test for interaction of diabetes on 3-year outcomes for all-cause mortality using adjusted hazard models

| HFrEF: ≤40% | HFbEF: >40% & <50% | HFpEF: ≥50%. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P for interaction | HR (95% CI) | P for interaction | HR (95% CI) | P for interaction | |

| Age (y) | ||||||

| ≥75 | 1.12 (1.05–1.20) | .1040 | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) | .1617 | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) | .0270 |

| <75 | 1.19 (1.09–1.30) | 1.22 (1.06–1.40) | 1.13 (1.03–1.25) | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1.28 (1.16–1.42) | .0195 | 1.20 (1.04–1.39) | .7816 | 1.17 (1.07–1.28) | .2554 |

| Male | 1.19 (1.09–1.30) | 1.22 (1.06–1.40) | 1.13 (1.03–1.25) | |||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1.19 (1.09–1.30) | .0031 | 1.22 (1.06–1.40) | .2899 | 1.13 (1.03–1.25) | .9041 |

| African American | 1.04 (0.93–1.18) | 1.14 (0.93–1.41) | 1.15 (1.01–1.31) | |||

| Hispanic | 1.02 (0.87–1.20) | 1.11 (0.81–1.52) | 1.16 (1.00–1.36) | |||

| Asian | 1.36 (1.16–1.61) | 1.38 (1.09–1.74) | 1.07 (0.91–1.27) | |||

| Renal insufficiency | ||||||

| None | 1.19 (1.09–1.30) | .6522 | 1.22 (1.06–1.40) | .3651 | 1.13 (1.03–1.25) | .4760 |

| Present | 1.21 (1.11–1.31) | 1.30 (1.13–1.50) | 1.10 (1.00–1.21) | |||

Reference no diabetes.

With respect to the all-cause readmission end point, diabetes was a greater risk among those younger than 75 years (P for interaction = .0501) for HFrEF patients (Table IVB). For HFbEF and HFpEF patients, female patients with diabetes were at greater risk for readmission (P for interaction = .0096 and .0075). Among HFpEF patients, white and Asian patients had greater readmission risk related to the presence of diabetes (P for interaction = .0153).

Table IVB.

Test for interaction of diabetes on 3-year outcomes for all-cause readmissions using adjusted hazard models

| HFrEF: ≤40% | HFbEF: >40% & <50% | HFpEF: ≥50%. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P for interaction | HR (95% CI) | P for interaction | HR (95% CI) | P for interaction | |

| Age (y) | ||||||

| ≥75 | 1.13 (1.01–1.27) | .0501 | 1.08 (1.02–1.15) | .1151 | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) | .2430 |

| <75 | 1.33 (1.11–1.60) | 1.14 (1.06–1.23) | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1.32 (1.09–1.60) | .8772 | 1.22 (1.14–1.31) | .0096 | 1.18 (1.09–1.27) | .0075 |

| Male | 1.33 (1.11–1.60) | 1.14 (1.06–1.23) | 1.10 (1.03–1.25) | |||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1.33 (1.11–1.60) | .3219 | 1.14 (1.06–1.23) | .6304 | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) | .0153 |

| African American | 1.12 (0.88–1.42) | 1.13 (1.01–1.26) | 1.02 (0.93–1.12) | |||

| Hispanic | 1.31 (0.96–1.80) | 1.20 (1.05–1.38) | 1.04 (0.92–1.17) | |||

| Asian | 1.31 (0.94–1.84) | 1.12 (0.98–1.28) | 1.28 (1.11–1.46) | |||

| Renal insufficiency | ||||||

| None | 1.33 (1.11–1.60) | .2674 | 1.14 (1.06–1.23) | .3424 | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) | .5579 |

| Present | 1.23 (1.04–1.46) | 1.11 (1.03–1.20) | 1.13 (1.04–1.22) | |||

Reference no diabetes.

Discussion

This large study describes the clinical characteristics and long-term outcomes of patients hospitalized for HF with and without diabetes. The analysis was stratified by HF subtype to evaluate the differential associations of diabetes status with long-term outcomes. Overall, we find that HF patients with diabetes are younger and more likely to have ischemic heart disease and additional comorbidities. While controlling for baseline factors and comorbidities, we find that diabetes is independently associated with an additional mortality and readmission risk for HFrEF patients. Among HFbEF and HFpEF patients, diabetes has no appreciable association with all-cause mortality but is associated with substantially higher readmission risk for HFbEF patients. Among HFpEF patients, diabetes status does not appear to be associated with additional mortality risk but may be associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular readmission.

Prior research has shown that a hospitalized patient’s diabetes status may influence inpatient mortality risk, although a prior study from OPTIMIZE-HF found no association of diabetes with in-hospital or 60- to 90-day mortality rates.5,17 For HFrEF patients, a secondary analysis of the PARADIGM-HF trial showed that diabetes and hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) level were associated with a significantly higher hazard for both mortality and hospitalizations after a median follow-up of 26 months.18 Similar findings were seen among diabetes patients with ischemic HFrEF in the EPHESUS trial.19 Although our findings are not stratified by HbA1C levels, the risk we present is consistent with prior findings among HFrEF patients.

When accounting for other comorbidities, diabetes is a risk factor for incident HFpEF and theorized to contribute to disease severity.20,21 Secondary analyses of older multinational randomized controlled trials that recruited patients with HFpEF have estimated significant hazards for all-cause mortality and readmission secondary to comorbid diabetes.22–25 These reported GWTG-HF long-term outcomes did not reflect a significant risk differential related to comorbid diabetes for patients with HFpEF in a much larger US Medicare population when controlling for other clinical and hospital factors. The differences between these findings and the prior literature may relate to the older age of GWTG-HF cohort and higher baseline event rates for both populations with and without diabetes. Additionally, GWTG-HF is a US rather than multinational cohort where systems of care and treatment strategies for both HF and diabetes may differ. The GWTG-HF cohort had higher rates of comorbid conditions compared to the relatively healthier HFpEF cohorts recruited to multinational clinical trials. Therefore, as an isolated risk factor among many, the impact of diabetes may not have been as perceptible. The adjusted statistical models included both hospital and clinical factors that may not have been adjusted in the prior work and confounded prior associations with diabetes. Given the lack of evidence-based treatment strategies for HFpEF, these results may reflect the inability to improve outcomes once hospitalized for symptomatic HFpEF with current management strategies. The application of novel drug classes to the HFpEF patient population may help address major treatment gaps. The upcoming PARAGON-HF trial using sacubitril/valsartan and SGLT2 inhibitor trials will evaluate improvements in clinical outcomes for patients with HFpEF.26,27

Despite the smaller sample size, among HFbEF patients, we find a strong association with increased readmission risk among patients with diabetes without a clear mortality risk after adjusting for other comorbidities. Diabetes may be associated with greater severity of HF symptoms and difficulty with volume regulation given the higher risk of cardiovascular specific readmission. Diabetes imparts observable metabolic shifts that contribute to myocardial dysfunction and fluid balance. Insulin resistance results in increased free fatty acid metabolism and decreased glycolysis in the myocyte leading to increased oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction.28 Diabetes may also be a marker for other unmeasured patient factors not adjusted for in the hazard model that predispose these patients to increased inpatient utilization.

Secondary analyses from the EMPA-REG Outcome trial found that both the risk for HF hospitalization and cardiovascular death were reduced with SGLT-2 inhibition among patients with and without HF.29 A 39% reduction in hazard was noted for hospitalization or death from HF. There were also improvements in HF-related outcomes in the CANVAS trials. Given the lack of evidence for other hyperglycemic medication classes in reducing cardiovascular or mortality outcomes, SGLT2 inhibitors should be given consideration for HF patients with diabetes of all subtypes without contraindications to treatment. The Effect of Sotagliflozin on Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Post Worsening Heart Failure (SOLOISTWHF) trial will be further evaluating the effect of an SGLT-1/2 inhibitor on outcomes in patients hospitalized with HF (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03521934).

Limitations

These data are from patients with Medicare insurance and hospitals participating in GWTG-HF and may not apply to patients and care settings that substantially differ. Diabetes status was ascertained primarily based on clinical chart abstraction definitions for patients participating in the GWTG-HF registry, and some patients may have had undiagnosed diabetes and been misclassified. We did not attempt to model severity of diabetes based on HbA1C levels, as nearly 90% did not have these laboratory values available on index admission. We also did not consider the severity of diabetes based on the duration of diabetes or number of hyperglycemic medications. The younger age of patients with diabetes patients suggests an overall survival bias for nondiabetes patients with HF; therefore, the risks related to comorbid diabetes are likely underappreciated from the population perspective. Residual measured and unmeasured confounding may have influenced the findings.

Conclusion

HF patients with HFrEF and HFbEF aged 65 years or older with diabetes are at increased risk for mortality and rehospitalization after an index hospitalization, independent of patient and hospital characteristics. Diabetes does not appear to be associated with significant additional risk among patients with HFpEF when adjusting for other known patient and hospital characteristics. The increasing prevalence of diabetes nationally overall and among HF patients is a cause for alarm and a complicating factor in other severe chronic diseases. Public health interventions are desperately needed to stem the tide of both diabetes and HF. Diabetes imparts differential trajectories and risk of mortality and readmission depending on the subtype of HF based on LVEF assessment. Given the elevated rates of mortality and rehospitalization among these HF patients, identification of treatment strategies and novel therapeutics is needed to improve further patient outcomes with HF and diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

The Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) program is provided by the American Heart Association (AHA). GWTG-HF is sponsored, in part, by Amgen Cardiovascular and has been funded in the past through support from Medtronic, GlaxoSmithKline, Ortho-McNeil, and the AHA Pharmaceutical Roundtable. B. Ziaeian is supported by the ACC Presidential Career Developmental Award and AHA SDG 17SDG33630113.

Disclosures

Boback Ziaeian: none, bziaeian@mednet.ucla.edu

Adrian F. Hernandez: research support from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and Novartis and honoraria from Bayer, Boston Scientific and Novartis, adrian.hernandez@duke.edu

Adam D. DeVore: research: American Heart Association, Amgen, NHLBI Novartis; consulting: Novartis, adam.devore@duke.edu

Jinjing Wu: none, jingjing.wu@duke.edu

Paul A. Heidenreich: none, heiden@stanford.edu

Roland A. Matsouaka: none, roland.matsouaka@duke.edu

Deepak L. Bhatt: Advisory Board: Cardax, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, Medscape Cardiology, and Regado Biosciences; Board of Directors: Boston VA Research Institute, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, and TobeSoft; Chair: American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; Data Monitoring Committees: Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute, for the PORTICO trial, funded by St. Jude Medical, now Abbott), Cleveland Clinic, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (for the ENVISAGE trial, funded by Daiichi Sankyo), Population Health Research Institute; honoraria: American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org; Vice-Chair, ACC Accreditation Committee), Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute; RE-DUAL PCI clinical trial steering committee funded by Boehringer Ingelheim), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees), HMP Global (Editor in Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), Population Health Research Institute (for the COMPASS operations committee, publications committee, steering committee, and USA national co-leader, funded by Bayer), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees); other: Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); research funding: Abbott, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Eisai, Ethicon, Forest Laboratories, Idorsia, Ironwood, Ischemix, Lilly, Medtronic, PhaseBio, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, Synaptic, The Medicines Company; royalties: Elsevier (Editor, Cardiovascular Intervention: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease); site co-investigator: Biotronik, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott), Svelte; trustee: American College of Cardiology; unfunded research: Novo Nordisk FlowCo, Merck, PLx Pharma, Takeda. dlbhattmd@post.harvard.edu

Clyde W. Yancy: none, cyancy@nm.org

Gregg C. Fonarow: research: NIH; consulting: Abbott, Amgen, Bayer, Janssen, Medtronic, and Novartis, gfonarow@mednet.ucla.edu

Footnotes

Appendix. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2019.01.006.

References

- 1.Allen LA, Fonarow GC, Liang L, et al. Medication initiation burden required to comply with heart failure guideline recommendations and hospital quality measures. Circulation [Internet] 2015;132 (14):1347–53. Available from: http://circ.ahajournals.org/lookup/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.014281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geiss LS, Wang J, Cheng YJ, et al. Prevalence and incidence trends for diagnosed diabetes among adults aged 20 to 79 years, United States, 1980–2012. Jama [Internet] 2014;312 (12):1218–26. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25247518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. Long-term trends in diabetes. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data 2016.

- 4.Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and aetiology of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol [Internet] 2016. June;13 (6):1–11. Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/nrcardio.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Win TT, Davis HT, Laskey WK. Mortality among patients hospitalized with heart failure and diabetes mellitus. Circ Hear Fail [Internet] 2016;9 (5), e003023 Available from: http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/lookup/doi/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.003023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Xu H, DeVore AD, et al. Temporal trends and factors associated with diabetes mellitus among patients hospitalized with heart failure: findings from Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure registry. Am Heart J [Internet] 2016;182:9–20, 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.07.025. [Available from:]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma A, Zhao X, Hammill BG, et al. Trends in noncardiovascular comorbidities among patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Hear Fail [Internet] 2018;11 (6), e004646 Available from: http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/lookup/doi/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy revisited. Circulation 2007;115 (25):3213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavender MA, Steg PG, Smith SC, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on hospitalization for heart failure, cardiovascular events, and death: outcomes at 4 years from the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry. Circulation 2015;132 (10): 923–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Organized program to initiate lifesaving treatment in hospitalized patients with heart failure (OPTIMIZE-HF): Rationale and design. Am Heart J 2004;148 (1):43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smaha LA. The American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines Program. Am Heart J 2004;148 (5 SUPPL). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013;128:e240–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J [Internet] 2016;37 (27):2129–200. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27207191. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng RK, Cox M, Neely ML, et al. Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction in the Medicare population. Am Heart J [Internet] 2014;168 (5):721–730.e3. [cited 2015 Jan 19;Available from] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25440801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vivo RP, Krim SR, Liang L, et al. Short- and long-term rehospitalization and mortality for heart failure in 4 racial/ethnic populations. J Am Heart Assoc [Internet] 2014;3 (5):e001134 Available from: http://jaha.ahajournals.org/cgi/doi/10.1161/JAHA.114.001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eapen ZJ, McCoy LA, Fonarow GC, et al. Utility of socioeconomic status in predicting 30-day outcomes after heart failure hospitalization. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8 (3):473–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg BH, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Influence of diabetes on characteristics and outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure: a report from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF). Am Heart J 2007;154 (4):647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristensen SL, Preiss D, Jhund PS, et al. Risk related to pre–diabetes mellitus and diabetes mellitus in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to determine impact on global mortality and morbidity in heart failure trial. Circ Heart Fail 2016;9 (1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deedwania PC, Ahmed MI, Feller MA, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction and systolic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13 (5):551–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62 (4):263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mentz RJ, Kelly JP, Von Lueder TG, et al. Noncardiac comorbidities in heart failure with reduced versus preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64 (21):2281–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDonald MR, Petrie MC, Varyani F, et al. Impact of diabetes on outcomes in patients with low and preserved ejection fraction heart failure—an analysis of the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) programme. Eur Heart J 2008;29 (11):1377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kristensen SL, Mogensen UM, Jhund PS, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics and cardiovascular outcomes according to diabetes status in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a report from the I-Preserve Trial (Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection). Circulation [Internet] 2017;135 (8):724–35. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28052977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandesara PB, O’Neal WT, Kelli HM, et al. The prognostic significance of diabetes and microvascular complications in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Diabetes Care 2018;41 (1):150–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tribouilloy C, Rusinaru D, Mahjoub H, et al. Prognostic impact of diabetes mellitus in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a prospective five-year study. Heart [Internet] 2008;94 (11): 1450–34. Available from: http://heart.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/hrt.2007.128769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon SD, Rizkala AR, Gong J, et al. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: rationale and design of the PARAGON-HF trial. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5 (7):471–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehrke M, Marx N. Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure. Am J Cardiol 2017;120 (1):S37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dei Cas A, Khan SS, Butler J, et al. Impact of diabetes on epidemiology, treatment, and outcomes of patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3 (2):136–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitchett D, Zinman B, Wanner C, et al. Heart failure outcomes with empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk: results of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME® trial. Eur Heart J 2016;37 (19):1526–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.