Abstract

Background

Sigh is a cyclic brief recruitment maneuver: previous physiologic studies showed that its use could be an interesting addition to pressure support ventilation to improve lung elastance, decrease regional heterogeneity, and increase release of surfactant.

Research Question

Is the clinical application of sigh during pressure support ventilation (PSV) feasible?

Study Design and Methods

We conducted a multicenter noninferiority randomized clinical trial on adult intubated patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure or ARDS undergoing PSV. Patients were randomized to the no-sigh group and treated by PSV alone, or to the sigh group, treated by PSV plus sigh (increase in airway pressure to 30 cm H2O for 3 s once per minute) until day 28 or death or successful spontaneous breathing trial. The primary end point of the study was feasibility, assessed as noninferiority (5% tolerance) in the proportion of patients failing assisted ventilation. Secondary outcomes included safety, physiologic parameters in the first week from randomization, 28-day mortality, and ventilator-free days.

Results

Two-hundred and fifty-eight patients (31% women; median age, 65 [54-75] years) were enrolled. In the sigh group, 23% of patients failed to remain on assisted ventilation vs 30% in the no-sigh group (absolute difference, –7%; 95% CI, –18% to 4%; P = .015 for noninferiority). Adverse events occurred in 12% vs 13% in the sigh vs no-sigh group (P = .852). Oxygenation was improved whereas tidal volume, respiratory rate, and corrected minute ventilation were lower over the first 7 days from randomization in the sigh vs no-sigh group. There was no significant difference in terms of mortality (16% vs 21%; P = .337) and ventilator-free days (22 [7-26] vs 22 [3-25] days; P = .300) for the sigh vs no-sigh group.

Interpretation

Among hypoxemic intubated ICU patients, application of sigh was feasible and without increased risk.

Trial Registry

ClinicalTrials.gov; No.: NCT03201263; URL: www.clinicaltrials.gov

Key Words: ARDS, feasibility, pressure support, sigh, ventilation

Abbreviations: AHRF, acute hypoxemic respiratory failure; ESICM, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine; PBW, predicted body weight; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; P-SILI, patient self-inflicted lung injury; PSV, pressure support ventilation; RCT, randomized clinical trial; SBT, spontaneous breathing trial; Spo2, peripheral oxygen saturation

Take-home Points.

Study Question: The aim of this randomized clinical trial was to determine the feasibility of the application of sigh during pressure support ventilation (PSV).

Results: The study showed that in mechanically ventilated patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure or ARDS, addition of sigh in comparison with no sigh during PSV was feasible and safe: there was no increase in patients failing to remain on assisted ventilation (23% vs 30%, respectively), and there were similar proportions of adverse events (12% vs 13%, respectively).

Interpretation: Addition of sigh to PSV is feasible and safe in intubated ICU patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure or ARDS.

Mechanical ventilation is a vital support for intubated patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF) and ARDS.1 , 2 Early switch to assisted ventilation modes carries significant benefits, including reduced sedation and improved hemodynamics.2 Approximately 30% of invasively ventilated patients breathe spontaneously by day 1 from intubation and, by day 7, pressure support ventilation (PSV) is the most widely used mode of ventilation worldwide.3

Multiple physiologic studies showed that use of sighs could be an interesting addition to pressure support ventilation. Sigh may improve lung function through improved lung elastance,4 decreased regional heterogeneity,5 increased release of active surfactant,6 and decreased effort,5 the latter being protective also for the diaphragm. Moreover, sigh has been shown to allow a reduction in tidal volume and respiratory rate, reducing the ventilation load applied to the lungs.4 , 5 , 7 These studies generated the hypothesis that addition of sigh to PSV might improve clinical outcomes of patients with AHRF and ARDS. However, no randomized clinical trial (RCT) on sigh addition to PSV has ever been performed, and, before conducting a larger trial aimed at verifying improved survival, we first conceived a pilot RCT to verify the clinical feasibility of sigh in comparison with standard PSV8 and to have preliminary estimates of adverse events, loss to follow-up, outcomes, and its variabilities. A noninferiority approach was chosen to demonstrate that application of sigh in the clinical setting is as feasible as standard PSV, which is the most widely adopted assisted ventilation mode.

In the present trial, sigh was applied early after switching to PSV in intubated patients with AHRF or ARDS and maintained until successful weaning, death, or day 28. The study aimed at attesting the noninferiority of sigh, as compared with standard PSV without sigh, in terms of failure of assisted ventilation. Failure was defined as the occurrence of any of the following conditions: switch back to controlled ventilation, use of rescue therapies for refractory hypoxemia, and reintubation.

Secondary outcomes included comparison between the two study arms in the incidence of adverse events, physiologic parameters, survival, and ventilator-free days.

Methods

Study Design and Population

The present study was a pilot RCT conducted between December 2017 and May 2019 at the ICUs of 20 hospitals from eight countries: Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, Germany, Slovenia, Greece, China, and Brazil. Centers were recruited through a call to members of the Pleural Pressure Working Group (PLUG) of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) and through publication of the protocol on the ESICM website. The ESICM also endorsed and funded, in part, the study. The study design and statistical analysis plan have been published.8 This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico (international leading coordination center, June 6, 2017, No. 318). The institutional review boards of all centers approved the trial. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov.9 Informed consent was obtained for all individual participants included in the study, in accordance with local regulations. The trial enrolled patients admitted to each participating ICU and receiving invasive ventilation for > 24 h and ≤ 7 days, undergoing PSV for ≥ 4 and ≤ 24 h, with a Pao 2/Fio 2 ratio ≤ 300 mm Hg and clinical positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) ≥ 5 cm H2O. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale10 value at enrollment had to be between –2 and 0. Exclusion criteria can be found in e-Appendix 1.

Sigh Test, Randomization, and Interventions

After enrollment, all patients underwent a 30-min test of addition of sigh to clinical PSV to assess the prevalence of sigh responders vs nonresponders as defined by improved oxygenation. Briefly, the ventilator Fio 2 was titrated to obtain a peripheral oxygen saturation (Spo 2) of 90% to 96%, while keeping the same clinical PEEP and PSV levels. Sigh was then added as a pressure control phase set at total end-inspiratory pressure of 30 cm H2O for a 3-s insufflation time, once per minute. At the beginning and after 30 min, the Spo 2/Fio 2 ratio was determined. On the basis of a previous physiologic study, the expected prevalence of sigh responders (ie, patients improving Spo 2/Fio 2 by > 1%) was estimated to be 50%.5

After completion of the sigh test, patients were randomized by a 1:1 ratio to a strategy of PSV titrated according to a predefined protocol with addition of sigh (sigh group) or to a strategy of PSV titrated according to the same protocol but without sigh (no-sigh group). The local investigators randomized patients using a central, dedicated, password-protected, web-based, automated randomization system. The randomization sequence was generated using a permuted blocks randomization scheme (block size of six).

After randomization, in the sigh group, PSV was targeted to a tidal volume of 6 to 8 mL/kg of predicted body weight (PBW), with a respiratory rate 20 to 35 breaths/min (bpm) and clinical PEEP. Fio 2 was left as selected during the prerandomization sigh test. Sigh was promptly added as a pressure control breath at total end-inspiratory pressure of 30 cm H2O for 3 s delivered once per minute. Ventilators were switched to biphasic synchronized positive airway pressure mode (also known as synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation combining pressure control and PSV) with the lower pressure level set at clinical PEEP and the higher pressure level set at 30 cm H2O with a 3-s inspiratory time. Sigh settings were left unchanged until switch to controlled ventilation, day 28, death, or performance of a successful spontaneous breathing trial (SBT; see below). In the no-sigh group, after randomization, PSV was set to obtain the same targets as above with clinical PEEP and the Fio 2 selected during the prerandomization sigh test.

Then, in both groups at least every 8 h, the PSV level was adjusted to maintain a tidal volume of 6 to 8 mL/kg PBW and respiratory rate of 20 to 35 bpm, while PEEP and Fio 2 were managed to keep the Spo 2 at 90% to 96%.

In both groups, switch to protective controlled ventilation was indicated when patients fulfilled specific predefined criteria.8 Patients switched to controlled ventilation were reassessed at least every 8 h and switched back to the sigh or no-sigh group as soon as predefined criteria for improvement were met.8

Patients with Spo 2 ≥ 90% on Fio 2 ≤ 0.4 and PEEP ≤ 5 cm H2O, no agitation, and who were hemodynamically stable underwent an SBT. For patients in the sigh group, the attending physician withdrew sigh, waited 60 min, confirmed the above-mentioned criteria, and performed the SBT; if criteria were no longer met, sigh was reintroduced and this procedure was repeated after at least 8 h. The SBT lasted at least 60 min with a combination of PEEP of 0 to 5 cm H2O and PSV level of 0 to 5 cm H2O. Criteria for success vs failure of the SBT were predefined by study protocol.8 Subjects successfully completing the SBT were promptly extubated or, in the presence of tracheostomy, mechanical ventilation was discontinued. Patients who failed the SBT were switched back to the sigh or no-sigh group, and criteria for SBT were checked again after at least 6 h. After extubation, reintubation was performed if at least one of the criteria predefined by the study protocol was present.8

Outcomes

The primary end point of this trial8 was to assess noninferiority of sigh feasibility vs no sigh by comparing the number of patients in each group experiencing at least one of the following criteria for failure of assisted ventilation: switch to controlled ventilation for ≥ 24 h (consecutive); use of rescue therapy; and reintubation within 48 h.

Secondary outcomes included the following: comparison of selected physiologic variables during the first 7 days from randomization in the two study groups; evaluation of the clinical safety of sigh vs no sigh by comparing the incidence of predefined adverse events; quantification of responders and nonresponders to the prerandomization sigh test; 28-day mortality and ventilator-free days in the two study groups and in responders and nonresponders.

Statistical Analysis

On the basis of previous data,11 we computed that a sample size of 258 patients (with 129 patients per study arm) was sufficient to assess feasibility of the sigh strategy (primary outcome), using a noninferiority test with a tolerance of 5%, power of 0.8, α 0.05, and 22% and 15% as the expected rate of failure of assisted ventilation in patients undergoing no-sigh and sigh treatment, respectively. Failure of assisted ventilation in patients treated with sigh was compared with patients with no sigh, using a one-tailed noninferiority test for proportions with a 5% tolerance. In details, noninferiority of sigh was established when failure in the sigh group was lower than failure of no sigh plus 5%. This is the standard alternative hypothesis for noninferiority tests.12 Thus, in this study, a P value less than .05 (type I error) for the noninferiority test would reject inferiority of the new treatment (sigh) compared with no sigh. Survival at day 28 was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves, and the log-rank test was used to test differences between curves.

Continuous variables are described by mean and SD when normally distributed or as median and interquartile range otherwise. Categorical variables are reported as number and proportion (%). Statistical significance of differences between the two study groups (sigh vs no sigh) was tested using χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, t-test for continuous normally distributed variables, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nonnormally distributed continuous variables.

To test differences in time trends of physiologic and clinical parameters between the two study groups we used generalized estimating equation models to account for repeated measures.

Results

Patients

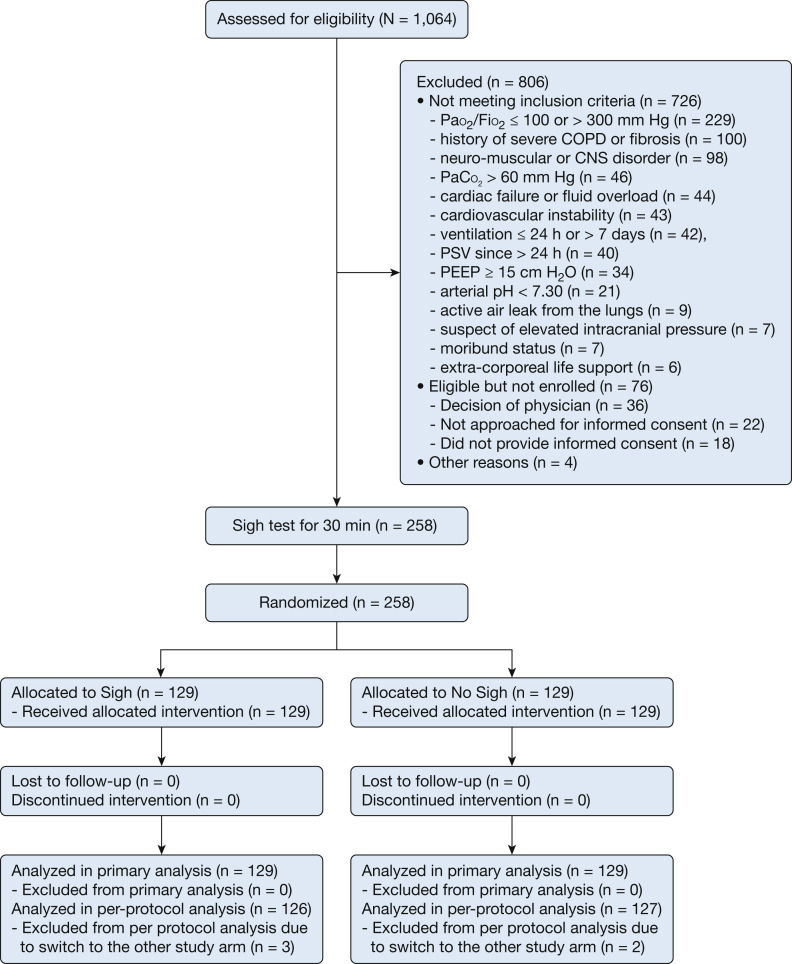

One thousand and sixty-four intubated ICU patients undergoing PSV were screened. A total of 806 were not enrolled, of whom 726 (90%) met at least one of the exclusion criteria and 80 (10%) were eligible but could not be enrolled for various reasons (Fig 1 ). Two hundred and fifty-eight patients completed the sigh test and were subsequently randomized, 129 to the sigh group and 129 to the no-sigh group. None of the patients withdrew consent after randomization. Sigh was applied for 4 (2-9) days in the sigh group. Follow-up until day 28 was complete for all patients. Data for 258 subjects (129 in each group) were considered for the primary intention-to-treat analysis (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of patients in the trial. PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure; PSV = pressure support ventilation.

Three patients in the sigh group and two patients in the PSV group were not included in the per-protocol analysis because of switch to the other study arm, due to adverse event, discomfort, and hypoxemia; 126 patients in the sigh group and 127 in the no-sigh group were kept for the per-protocol analysis.

Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two study groups (Table 1 ). Men represented 67% (87 patients) and 71% (92 patients) in the sigh group and in the no-sigh group, respectively. The mean age of patients was 63 ± 15 years, with no significant difference between groups. The prevalence of comorbidities and general severity at admission were comparable (Table 1). The prevalence of the diagnosis of ARDS was 46% in the sigh group and 53% in the no-sigh group, with nonsignificant difference (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristics | Sigh (n = 129) |

No Sigh (n = 129) |

P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Men, No. (%) | 87 (67) | 92 (71) | .499 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63 (17) | 63 (14) | .676 |

| Height, median (Q1, Q3), cm | 170 (165, 178) | 170 (160, 176) | .298 |

| Predicted body weight, median (Q1, Q3), kg | 80 (67, 90) | 78 (65, 86) | .432 |

| BMI, median (Q1, Q3), kg/m2 | 26.1 (23.4, 31.0) | 26.2 (23.5, 29.7) | .967 |

| Comorbidities, No. (%) | |||

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 66 (51) | 79 (61) | .103 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 19 (15) | 27 (21) | .193 |

| Diabetes | 26 (20) | 28 (22) | .735 |

| Chronic renal disease | 14 (11) | 24 (19) | .079 |

| Cancer | 13 (10) | 18 (14) | .338 |

| No. of comorbidities, No. (%) | |||

| 0 | 40 (34) | 32 (25) | .199 |

| 1 | 48 (37) | 44 (35) | |

| 2 | 23 (18) | 31 (24) | |

| ≥ 3 | 14 (11) | 21 (16) | |

| Recent medical history | |||

| In-hospital days, median (Q1, Q3) | 5 (3, 8) | 5 (3, 8) | .785 |

| ICU days, median (Q1, Q3) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | .513 |

| Intubation days, median (Q1, Q3) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 4) | .358 |

| SAPS II, median (Q1, Q3) | 42 (32, 55) | 42 (32, 56) | .796 |

| SOFA, median (Q1, Q3) | 7 (5, 10) | 7.5 (5, 9) | .857 |

| RASS, No. (%) | |||

| –2 | 64 (50) | 72 (56) | .588 |

| –1 | 27 (21) | 25 (19) | |

| 0 | 38 (29) | 32 (25) | |

| Diagnosis of sepsis, No. (%) | |||

| Sepsis | 43 (33) | 39 (30) | .144 |

| Septic shock | 20 (15) | 35 (27) | |

| No sepsis | 60 (47) | 51 (40) | |

| Not specified | 6 (5) | 4 (3) | |

| Etiology | |||

| Pneumonia, No. (%) | 79 (61) | 75 (58) | .612 |

| Aspiration of gastric content, No. (%) | 15 (12) | 11 (9) | .408 |

| Vasculitis, No. (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.000 |

| Nonpulmonary sepsis, No. (%) | 20 (16) | 24 (19) | .508 |

| Trauma, No. (%) | 8 (6) | 6 (5) | .583 |

| Pancreatitis, No. (%) | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 1.000 |

| Burns, No. (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.000 |

| TRALI, No. (%) | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | .702 |

| Other, No. (%) | 15 (12) | 16 (12) | .848 |

| Pulmonary infiltrates, No. (%) | |||

| None | 28 (22) | 22 (17) | .427 |

| Unilateral | 42 (33) | 38 (30) | |

| Bilateral (ARDS diagnosis) | 59 (46) | 69 (53) | |

| PEEP, median (Q1, Q3), cm H2O | 10 (8, 12) | 10 (8, 11) | .487 |

| PSV, median (Q1, Q3), cm H2O | 10 (8, 12) | 10 (8, 12) | .967 |

| RR, median (Q1, Q3), bpm | 18 (10, 30) | 18 (15, 23) | .445 |

| pH, mean (SD) | 7.43 (0.05) | 7.43 (0.06) | .510 |

| Pao2/Fio2, median (Q1, Q3), mm Hg | 222 (192, 252) | 228 (187, 251) | .991 |

| Paco2, median (Q1, Q3), mm Hg | 44 (38, 49) | 43 (39, 47) | .695 |

Continuous data are reported as median (Q1, Q3) or mean (SD). Categorical data are reported as No. (%). bpm = breaths/min; PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure; PSV = pressure support ventilation; RASS = Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale; RR = respiratory rate; SAPS = Simplified Acute Physiology Score; SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; TRALI = transfusion-related acute lung injury.

Tests for differences between PSV plus sigh vs PSV: t-test or Wilcoxon, χ2, or Fisher, as appropriate.

Outcomes

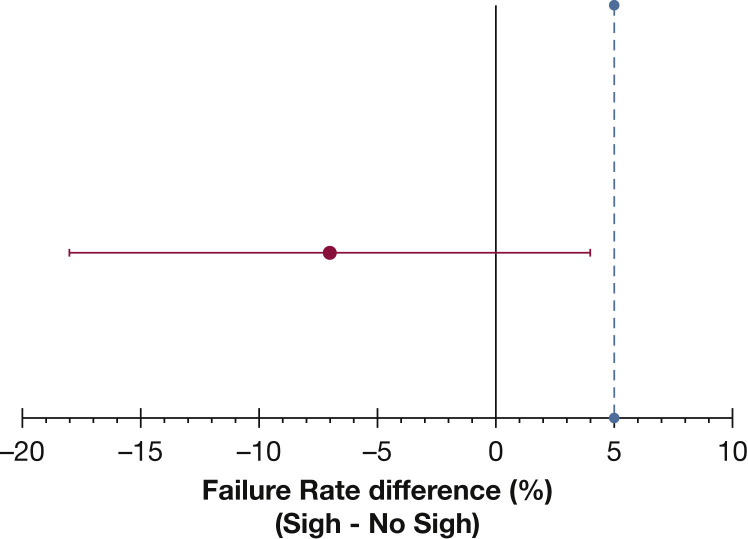

Twenty-eight days after randomization, 30 patients (23%) in the sigh group vs 39 (30%) in the no-sigh group (Table 2 ) experienced at least one criterion for failure of assisted ventilation. The sigh treatment group was therefore noninferior to the no-sigh treatment group in terms of failure of assisted ventilation (absolute difference, –7%; 95% CI, –18% to 4%; P = .015 for noninferiority test) (Fig 2 ). Specific reasons for failure of assisted ventilation and type of rescue treatment are shown in Table 2. Per-protocol analysis showed similar results with 29 patients (23%) failing to remain on assisted ventilation in the sigh group vs 37 (29%) in the no-sigh group (absolute difference, –6%; 95% CI, –17% to 5%; P = .022 for noninferiority test).

Table 2.

Study Outcomes

| Outcomes | Sigh (n = 129) |

No Sigh (n = 129) |

P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Failure of assisted ventilation, No. (%), noninferiority test | 30 (23) | 39 (30) | .015 |

| Reasons for failure | |||

| Switch to controlled MV ≥ 24 h, No. (%) | 15 (12) | 26 (20) | .061 |

| Rescue treatment for hypoxemia, No. (%) | 14 (11) | 19 (15) | .351 |

| Reintubation within 48 h, No. (%) | 13 (9) | 12 (9) | .833 |

| Type of rescue treatment, No. (%) | |||

| Recruitment maneuver | 9 (7) | 14 (11) | .735 |

| PEEP ≥ 15 cm H2O | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Prone position | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | |

| Reasons for switch to MV, No. (%) | |||

| Support > 20 cm H2O or arterial pH < 7.3 | 4 (3) | 8 (6) | .262 |

| PEEP ≥ 15 cm H2O or Pao2/Fio2 ≤ 100 mm Hg | 8 (6) | 8 (6) | |

| Hypotension or hypertension | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Active cardiac ischemia or unstable arrhythmias | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| RASS < –3 or RASS > 2 | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | |

| Necessity to perform diagnostic test | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | |

| Adverse events, No. (%) | 16 (12) | 17 (13) | .852 |

| Type of adverse event, No. (%) | |||

| Hemodynamic instability | 5 (4) | 6 (5) | 1.00 |

| Arrhythmias | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Barotrauma | 9 (7) | 9 (7) | |

| Sigh responders,b No. (%) | 73 (56) | 83 (64) | .609 |

| Tracheostomy, No. (%) | 22 (17) | 19 (15) | .441 |

| Deaths at 28 d, No. (%) | 21 (16) | 27 (21) | .337 |

| VFDs, median (Q1, Q3) | 22 (7, 26) | 22 (3, 25) | .300 |

| Length of ICU stay, median (Q1, Q3), d | 7 (3, 13) | 7 (5, 11) | .695 |

Continuous data are reported as median (Q1, Q3) or mean (SD). Categorical data are reported as No. (%). MV = mechanical ventilation; PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure; PSV = pressure support ventilation; RASS = Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale; VFDs = ventilator-free days.

Tests for differences between sigh and no sigh: noninferiority for “failure of assisted ventilation”; χ2 or Fisher for other variables.

Spo2/Fio2 increase > 1% during the prerandomization sigh test.

Figure 2.

Treatment difference for failure of assisted ventilation between study groups. Dot and error bars indicate absolute value and two-sided 95% CIs, respectively. The maximum tolerance accepted in this noninferiority randomized clinical trial was 5% (light blue dotted line).

Adverse events (ie, hemodynamic instability, arrhythmias, and barotrauma) did not differ between the two study groups (16 patients [12%] in the sigh group vs 17 patients [13%] in the no-sigh group; P = .852). Types of adverse events are described in Table 2.

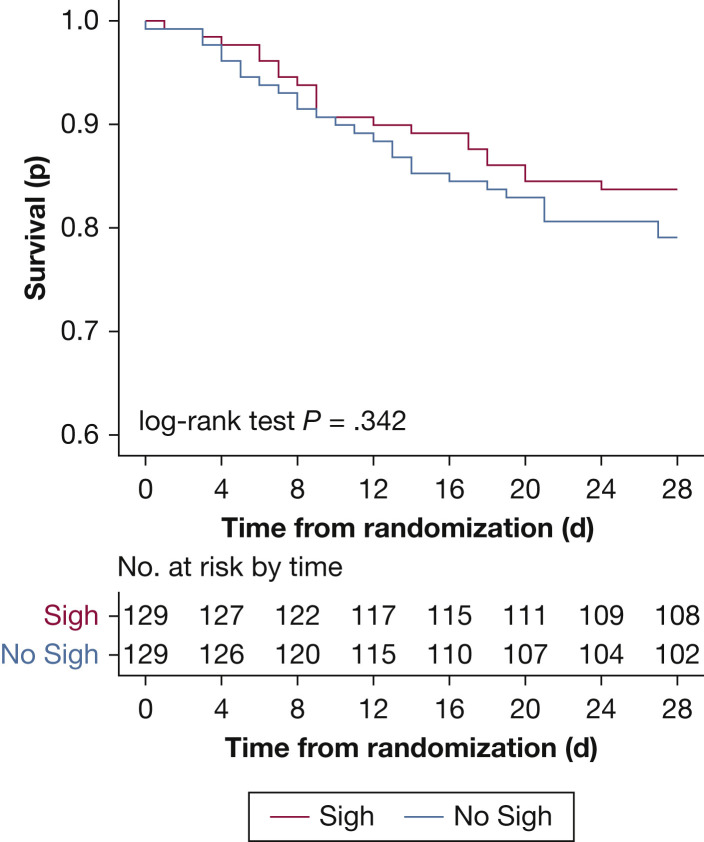

Twenty-one patients (16%) died by day 28 in the sigh group vs 27 patients (21%) in the no-sigh group (P = .337) (Table 2). Survival was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig 3 ) (P = .342 by log-rank test). Ventilator-free days on day 28 were 22 (7-26) days in the sigh group and 22 (3-25) in the no-sigh group (P = .300) (Table 2). The number of patients failing an SBT was 23 (18%) in the sigh group and 21 (16%) in the no-sigh group (P = .741). The number of SBTs failed was 1 (1-2) per patient for both groups, with no significant difference.

Figure 3.

Twenty-eight-day mortality in the study groups.

Outcomes in Responders and Nonresponders

Sigh responders, defined as patients in whom the Spo 2/Fio 2 ratio increased by > 1% during the sigh prerandomization test, numbered 156 (60%): 73 (47%) in the sigh group and 83 (53%) in the no-sigh group. Thus, nonresponders numbered 102: 56 (55%) in the sigh group and 46 (45%) in the no-sigh group. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics did not differ between the study groups both for responders and nonresponders (e-Table 1, e-Table 2). In responders, mortality was 16% (n = 12) in the sigh group vs 13% (n = 11) in the no-sigh group (P = .575). In nonresponders, mortality was 16% (n = 9) in the sigh group vs 35% (n = 16) in the no-sigh group (P = .029). Ventilator-free days did not differ in responders enrolled in the sigh vs no-sigh group (21 [5-26] vs 23 [15-25] days; P = .380). Ventilator-free days were significantly higher in nonresponders treated with sigh vs no sigh (23 [9-26] vs 10 [0-24] days; P = .006).

Physiology

Over the first 7 days from randomization, the PEEP level and set Fio 2 did not differ between groups. The Pao 2/Fio 2 ratio was significantly higher whereas the respiratory rate, tidal volume, and corrected minute ventilation (ie, the minute ventilation multiplied by actual Paco 2 divided by 40 mm Hg, with lower values indicating higher efficiency to clear CO2 by the respiratory system) were all significantly lower in the sigh group (e-Table 3, e-Fig 1). The tidal volume delivered by sigh in the first 7 days from randomization remained stable and approximately 15 mL/kg PBW (e-Fig 2). Paco 2 and pH, Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale score, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score were similar (e-Tables 3, 4, e-Fig 1).

Discussion

This randomized clinical trial showed the feasibility of adding sigh to PSV: the rate of failure of assisted ventilation was noninferior to conventional PSV. Secondary outcomes indicated the safety of sigh with a similar rate of adverse events, and comparable mortality and number of ventilator-free days. Moreover, improved physiology was confirmed in the first week from randomization by addition of sigh.

Sigh is commonly performed during quiet breathing by healthy subjects; it acts mainly as negative feedback on respiratory drive with positive functional and psychological consequences.13 Many studies performed both in hypoxemic patients14 , 15 and in animal models of lung injury16 showed that sigh is associated with improved physiology. Sigh induces recruitment of the collapsed lungs, restores surfactant production, decreases ventilation heterogeneity, improves regional mechanics, increases oxygenation, and modulates the inspiratory effort.5 , 17 On the other hand, sigh cyclically delivers large inspiratory volumes in patients in whom current guidelines recommend mandatory reduction of tidal volume.1 , 18 Because no study existed on the feasibility and safety of long-term application of sigh to hypoxemic patients, it seemed important to conceive a large noninferiority randomized controlled trial aimed at assessing the clinical feasibility and safety of sigh.

The present trial indicates that addition of sigh to PSV leads patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure or ARDS to experience failure of assisted ventilation at a rate similar to that of patients receiving traditional PSV. Moreover, the numbers of adverse events were similar and low, with only two patients per group experiencing barotrauma; in only two patients was sigh stopped to continue with traditional PSV; mortality and ventilator-free days did not differ. Taken together, these results suggest that sigh could be added to PSV without causing any additional risk and yielding similar clinical outcomes in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure or ARDS. Possible explanations for these findings could be that sigh was not able to produce any clinical benefits in comparison with PSV alone; or that the nonsignificant difference in mortality showed in this trial might become significant in a study performed with the same protocol but with a larger sample size.

Reduction of mortality with sigh in the subgroup of patients not responding in terms of oxygenation during a 30-min sigh test performed before randomization is an additional intriguing finding that will require confirmation.

Assisted ventilation carries the intrinsic risk of additional patient self-inflicted lung injury (P-SILI)19 and respiratory muscle myotrauma,20 making lung and diaphragm protection a key clinical goal.21 Limiting the inspiratory volume and transpulmonary pressure is the recommended strategy for hypoxemic patients receiving PSV to minimize the risk of P-SILI.22 , 23 We confirmed that sigh improves oxygenation and decreases respiratory rate, tidal volume, and minute ventilation during the first week, potentially decreasing the risk of additional P-SILI. As nonphysiologic high inspiratory pressure and volume leading to P-SILI increase the risk of prolonged ventilation and worse outcome,24 the physiologic analyses from this study might help in generating a more solid hypothesis on the clinical effects of sigh.

Our results suggest that sigh is easy to implement and could be seen as an alternative ventilation mode for ICU physicians, even in resource-limited settings.25

Sigh can be delivered for longer time periods (eg, from intubation), at a more physiologic lower rate (eg, once every other minute), and at different inspiratory pressures (eg, personalized based on transpulmonary pressure) than in our study. Sigh is not a general concept but rather a mechanical ventilation strategy with specific settings, and variability in the delivery of sigh may alter the results presented herein.

The present study has limitations. First, at enrollment, the patients had been receiving mechanical ventilation for 3 (2-5) days and sigh was applied only for approximately one-half the total number of days spent on mechanical ventilation. We cannot say whether application of sigh earlier and for a longer time period might lead to increased benefits (from improved physiology) or harm (from higher risks of cyclic overdistension and atelectrauma). However, application of sigh during controlled ventilation requires specific machines and we reasoned that sigh has specific advantages in patients undergoing assisted ventilation (eg, modulation of effort). Second, we delivered sigh at the same total inspiratory pressure in all patients, which, based on predictable differences in respiratory mechanics, could have determined variable levels of transpulmonary pressure. Response to the prerandomization sigh test might have been influenced by this, too, with nonresponders receiving insufficient volume. Personalized sigh settings based on specific patients’ characteristics could lead to a higher number of responders and improved outcomes. Third, the rate of sigh in this study was one per minute, whereas physiologic studies have suggested that a lower rate may be more effective.5 Once again, to our knowledge, only a few ventilators can deliver sigh during PSV once every 2 min. Fourth, because of the nature of the intervention, physicians and nurses attending patients enrolled in the study could not be blinded. However, we provided detailed protocols for changes in PSV settings, performance of rescue therapies, spontaneous breathing trials, extubation, and reintubation,8 which should have limited biases in primary outcomes. Fifth, we defined sigh responders on the basis of improvement of the Spo 2/Fio 2 ratio by > 1% during the prerandomization sigh test. This threshold could be seen as too low to be clinically meaningful; however, the analysis was exploratory and a higher threshold would have yielded large imbalances in group numbers.

Interpretation

Addition of sigh to PSV in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure or ARDS is as feasible as traditional PSV in terms of failure of assisted ventilation, and yields comparable adverse events, mortality, and ventilator-free days. Results from the present trial could inform the planning and design of larger clinical trials aimed at verifying reduced mortality by application of sigh.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: T. M. and A. P. had full access to all the data in the study and have final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Concept and design: T. M., J.-M. C., M. R., C. G., J. M., P. P., G. F., L. B., and A. P. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all of the authors. Drafting of the manuscript: T. M., C. F., and A. P. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all of the authors. Statistical analysis: C. F. Obtaining of funding: T. M. and A. P. Supervision: T. M., C. F., L. B., and A. P.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: T. M. received personal fees from Fisher & Paykel, Dräger, and Mindray outside of the present work. G. G. received payment for lectures from Dräger Medical, Getinge, Fisher & Paykel, Biotest, and Thermo Fisher; and travel/accommodation/congress registration support from Getinge and Biotest, all outside of the present work. O. R. received personal fees for consultancy from Hamilton Medical, and travel expenses from Air Liquide, all outside of the present work. T. B. received speaking fees from Dräger, Löwenstein Medical, and Sedana Medical, outside the submitted work. None declared (G. F., C. F., R. P., F. L., D. T., C. A. V., S. S., R. R., E. R., P. N., E. G., R. K., V. G., R. C., A. C., J.-X. Z., R. D’A., I. C., Á. V. G., D. L. G., T. J., D. Bampalis, D. Battaglini, H. G., M. L., J.-M. C., M. R., C. G., J. M., P. P., R. F., L. B., and A. P.).

PROTECTION Trial Collaborators: Plug working group of ESICM (Brussels, Belgium), Alessandra Papoff, MD (Niguarda, Milan, Italy), Raffaele Di Fenza, MD (Niguarda, Milan, Italy), Stefano Gianni, MD (Niguarda, Milan, Italy), Elena Spinelli, MD (Policlinico, Milan, Italy), Alfredo Lissoni, MD (Policlinico, Milan, Italy), Chiara Abbruzzese, MD (Policlinico, Milan, Italy), Alfio Bronco, MD (Monza, Italy), Silvia Villa, MD (Monza, Italy), Vincenzo Russotto, MD (Monza, Italy), Arianna Iachi, MD (Genoa, Italy), Lorenzo Ball, MD (Genoa, Italy), Nicolò Patroniti, MD (Genoa, Italy), Rosario Spina, MD (Empoli, Italy), Romano Giuntini, MD (Empoli, Italy), Simone Peruzzi, MD (Empoli, Italy), Luca Salvatore Menga, MD (Rome, Italy), Tommaso Fossali, MD (Sacco, Milan, Italy), Antonio Castelli, MD (Sacco, Milan, Italy), Davide Ottolina, MD (Sacco, Milan, Italy), Marina García-de-Acilu, MD (Barcelona, Spain), Manel Santafè, MD (Barcelona, Spain), Dirk Schädler, MD (Kiel, Germany), Norbert Weiler, MD (Kiel, Germany), Emilia Rosas Carvajal, MD (Madrid, Spain), César Pérez Calvo, MD (Madrid, Spain), Evangelia Neou, MD (Larissa, Greece), Yu-Mei Wang, MD (Beijing, China), Yi-Min Zhou, MD (Beijing, China), Federico Longhini, MD (Catanzaro, Italy), Andrea Bruni, MD (Catanzaro, Italy), Mariacristina Leonardi, MD (Catanzaro, Italy), Cesare Gregoretti, MD (Palermo, Italy), Mariachiara Ippolito, MD (Palermo, Italy), Zelia Milazzo, MD (Palermo, Italy), Lorenzo Querci, MD (Bologna, Italy), Serena Ranieri, MD (Bologna, Italy), Giulia Insom, MD (Bologna, Italy), Jernej Berden, MD (Ljubljana, Slovenia), Marko Noc, MD (Ljubljana, Slovenia), Ursa Mikuz, MD (Ljubljana, Slovenia), Matteo Arzenton, MD (Ferrara, Italy), Marta Lazzeri, MD (Ferrara, Italy), Arianna Villa, MD (Ferrara, Italy), Bruna Brandão Barreto, MD (Salvador, Brazil), Marcos Nogueira Oliveira Rios, MD (Salvador, Brazil), Dimitri Gusmao-Flores, MD (Salvador, Brazil), Mandeep Phull, MD (London, UK), Tom Barnes, MD (London, UK), Hussain Musarat, MD (London, UK), and Sara Conti, MD (University of Milan-Bicocca, Monza, Italy).

Role of sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit it.

Additional information: The e-Appendix, e-Figures, and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

Drs Brochard and Pesenti contributed equally to the present study.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: The PROTECTION trial was supported, in part, by an ESICM Clinical Research Award (ESICM, Brussels, Belgium) and by “Ricerca Corrente” of the Policlinico Hospital (Milan, Italy).

Contributor Information

PROTECTION Trial Collaborators:

Plug working group of ESICM, Alessandra Papoff, Raffaele Di Fenza, Stefano Gianni, Elena Spinelli, Alfredo Lissoni, Chiara Abbruzzese, Alfio Bronco, Silvia Villa, Vincenzo Russotto, Arianna Iachi, Lorenzo Ball, Nicolò Patroniti, Rosario Spina, Romano Giuntini, Simone Peruzzi, Luca Salvatore Menga, Tommaso Fossali, Antonio Castelli, Davide Ottolina, Marina García-de-Acilu, Manel Santafè, Dirk Schädler, Norbert Weiler, Emilia Rosas Carvajal, César Pérez Calvo, Evangelia Neou, Yu-Mei Wang, Yi-Min Zhou, Federico Longhini, Andrea Bruni, Mariacristina Leonardi, Cesare Gregoretti, Mariachiara Ippolito, Zelia Milazzo, Lorenzo Querci, Serena Ranieri, Giulia Insom, Jernej Berden, Marko Noc, Ursa Mikuz, Matteo Arzenton, Marta Lazzeri, Arianna Villa, Bruna Brandão Barreto, Marcos Nogueira Oliveira Rios, Dimitri Gusmao-Flores, Mandeep Phull, Tom Barnes, Hussain Musarat, and Sara Conti

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Brower R.G., Matthay M.A., Morris A., et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mauri T., Cambiaghi B., Spinelli E., Langer T., Grasselli G. Spontaneous breathing: a double-edged sword to handle with care. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(14):292. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.06.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellani G., Laffey J.G., Pham T., et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315(8):788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patroniti N., Foti G., Cortinovis B., et al. Sigh improves gas exchange and lung volume in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome undergoing pressure support ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(4):788–794. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200204000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mauri T., Eronia N., Abbruzzese C., et al. Effects of sigh on regional lung strain and ventilation heterogeneity in acute respiratory failure patients undergoing assisted mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(9):1823–1831. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massaro G.D., Massaro D. Morphologic evidence that large inflations of the lung stimulate secretion of surfactant. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127(2):235–236. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nacoti M., Spagnolli E., Bonanomi E., Barbanti C., Cereda M., Fumagalli R. Sigh improves gas exchange and respiratory mechanics in children undergoing pressure support after major surgery. Minerva Anestesiol. 2012;78(8):920–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauri T., Foti G., Fornari C., et al. PROTECTION Study Group Pressure support ventilation + sigh in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure patients: study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial, the PROTECTION trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):460. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2828-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. Sigh in Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure (PROTECTION). NCT03201263. ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03201263. Updated July 2, 2017.

- 10.Sessler C.N., Gosnell M.S., Grap M.J., et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1338–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xirouchaki N., Kondili E., Vaporidi K., et al. Proportional assist ventilation with load-adjustable gain factors in critically ill patients: comparison with pressure support. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11):2026–2034. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker E., Nowacki A.S. Understanding equivalence and noninferiority testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):192–196. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1513-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vlemincx E., Van Diest I., Van den Bergh O. A sigh following sustained attention and mental stress: effects on respiratory variability. Physiol Behav. 2012;107(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badet M., Bayle F., Richard J.C., Guerin C. Comparison of optimal positive end-expiratory pressure and recruitment maneuvers during lung-protective mechanical ventilation in patients with acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir Care. 2009;54(7):847–854. doi: 10.4187/002013209793800448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foti G., Cereda M., Sparacino M.E., De Marchi L., Villa F., Pesenti A. Effects of periodic lung recruitment maneuvers on gas exchange and respiratory mechanics in mechanically ventilated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(5):501–507. doi: 10.1007/s001340051196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tabuchi A., Nickles H.T., Kim M., et al. Acute lung injury causes asynchronous alveolar ventilation that can be corrected by individual sighs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(4):396–406. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0901OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moraes L., Santos C.L., Santos R.S., et al. Effects of sigh during pressure control and pressure support ventilation in pulmonary and extrapulmonary mild acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2014;18(4):474. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0474-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sweeney R.M., McAuley D.F. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet. 2016;388(10058):2416–2430. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00578-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brochard L., Slutsky A., Pesenti A. Mechanical ventilation to minimize progression of lung injury in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(4):438–442. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1081CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goligher E.C., Dres M., Fan E., et al. Mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragm atrophy strongly impacts clinical outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(2):204–213. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0536OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaporidi K., Akoumianaki E., Telias I., Goligher E.C., Brochard L., Georgopoulos D. Respiratory drive in critically ill patients: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(1):20–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0596SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertoni M., Telias I., Urner M., et al. A novel non-invasive method to detect excessively high respiratory effort and dynamic transpulmonary driving pressure during mechanical ventilation. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):346. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2617-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshida T., Uchiyama A., Matsuura N., Mashimo T., Fujino Y. Spontaneous breathing during lung-protective ventilation in an experimental acute lung injury model: high transpulmonary pressure associated with strong spontaneous breathing effort may worsen lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(5):1578–1585. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182451c40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida T., Amato M.B.P., Kavanagh B.P., Fujino Y. Impact of spontaneous breathing during mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019;25(2):192–198. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.