Abstract

Initial studies found increased severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), in patients with diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, COVID-19 might also predispose infected individuals to hyperglycaemia. Interacting with other risk factors, hyperglycaemia might modulate immune and inflammatory responses, thus predisposing patients to severe COVID-19 and possible lethal outcomes. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is part of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), is the main entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2; although dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) might also act as a binding target. Preliminary data, however, do not suggest a notable effect of glucose-lowering DPP4 inhibitors on SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility. Owing to their pharmacological characteristics, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors might cause adverse effects in patients with COVID-19 and so cannot be recommended. Currently, insulin should be the main approach to the control of acute glycaemia. Most available evidence does not distinguish between the major types of diabetes mellitus and is related to type 2 diabetes mellitus owing to its high prevalence. However, some limited evidence is now available on type 1 diabetes mellitus and COVID-19. Most of these conclusions are preliminary, and further investigation of the optimal management in patients with diabetes mellitus is warranted.

Subject terms: Type 2 diabetes, Epidemiology, Infectious diseases, Type 2 diabetes

The pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) and diabetes mellitus are interlinked, and diabetes mellitus is associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes. This Review highlights new advances in diabetes mellitus and COVID-19, considering disease mechanisms and clinical management of patients with diabetes mellitus in the ongoing pandemic.

Key points

Underlying diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases are considered risk factors for increased coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) disease severity and worse outcomes, including higher mortality.

Potential pathogenetic links between COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus include effects on glucose homeostasis, inflammation, altered immune status and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, tight control of glucose levels and prevention of diabetes complications might be crucial in patients with diabetes mellitus to keep susceptibility low and to prevent severe courses of COVID-19.

Evidence suggests that insulin and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors can be used safely in patients with diabetes mellitus and COVID-19; metformin and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors might need to be withdrawn in patients at high risk of severe disease.

Pharmacological agents under investigation for the treatment of COVID-19 can affect glucose metabolism, particularly in patients with diabetes mellitus; therefore, frequent blood glucose monitoring and personalized adjustment of medications are required.

As COVID-19 lacks definitive treatment so far, patients with diabetes mellitus should follow general preventive rules strictly and monitor glucose levels more frequently, engage in physical activity, eat healthily and control other risk factors.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the novel coronavirus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and has spread worldwide. As of 29 October 2020, 44,351,506 globally confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been reported on the World Health Organization COVID-19 dashboard, including 1,171,255 deaths. The fatality rate for COVID-19 has been estimated to be 0.5–1.0%1–3. From 1 March to 30 May 2020, 122,300 excess all-cause deaths occurred in the USA, of which 95,235 (79%) were officially attributed to COVID-19 (ref.4). Of note, mortality from COVID-19 and seasonal influenza is not equivalent, as deaths associated with these diseases do not reflect frontline clinical conditions in the same way. For example, COVID-19 pandemic-hit areas have been facing critical shortages in terms of access to supplies such as ventilators and intensive care unit (ICU) facilities5.

SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-stranded RNA virus that is enclosed by a protein-decorated lipid bilayer containing a single-stranded RNA genome; SARS-CoV-2 has 82% homology with human SARS-CoV, which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)6. In human cells, the main entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2 is angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)7, which is highly expressed in lung alveolar cells, cardiac myocytes, vascular endothelium and various other cell types8. In humans, the main route of SARS-CoV-2 transmission is through virus-bearing respiratory droplets9. Generally, patients with COVID-19 develop symptoms at 5–6 days after infection. Similar to SARS-CoV and the related Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 infection induces mild symptoms in the initial stage for 2 weeks on average but has the potential to develop into severe illness, including a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ involvement and shock10. Patients at high risk of severe COVID-19 or death have several characteristics, including advanced age and male sex, and have underlying health issues, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity and/or type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)11–13. A few early studies have shown that underlying CVD and diabetes mellitus are common among patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs14,15. T2DM is typically a disease of advanced age, and, therefore, whether diabetes mellitus is a COVID-19 risk factor over and above advanced age is currently unknown.

The basic and clinical science of the potential inter-relationships between diabetes mellitus and COVID-19 has been reviewed16. However, knowledge in this field is emerging rapidly, with numerous publications appearing frequently. This Review summarizes the new advances in diabetes mellitus and COVID-19 and extends the focus towards clinical recommendations for patients with diabetes mellitus at risk of or affected by COVID-19. Most available research does not distinguish between diabetes mellitus type and is mainly focused on T2DM, owing to its high prevalence. However, some limited research is available on COVID-19 and T1DM, which we highlight in this Review.

Potential mechanisms

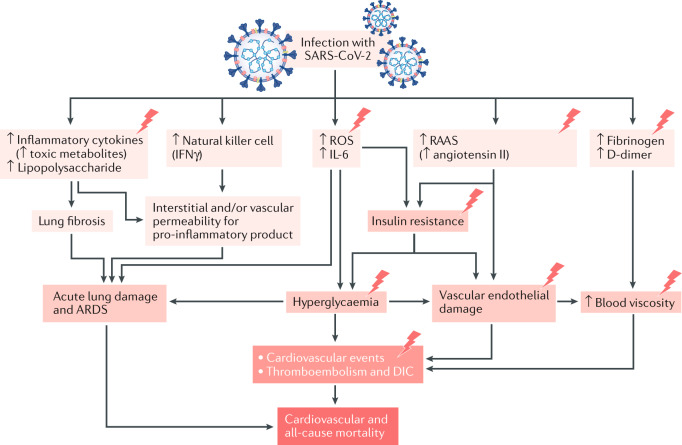

The presence of diabetes mellitus and the individual degree of hyperglycaemia seem to be independently associated with COVID-19 severity and increased mortality11,12,17,18. Furthermore, the presence of typical complications of diabetes mellitus (CVD, heart failure and chronic kidney disease) increases COVID-19 mortality11,19. We propose some pathophysiological mechanisms leading to increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality after infection with SARS-CoV-2 in patients with diabetes mellitus (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Potential pathogenic mechanisms in patients with T2DM and COVID-19.

Lightning bolts indicate mechanisms that are accentuated in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)7,239 can lead to increased levels of inflammatory mediators in the blood, including lipopolysaccharide240,241, inflammatory cytokines9,43,242,243 and toxic metabolites. Modulation of natural killer cell activity (increased9,39,50 or decreased242,244) and IFNγ production can increase the interstitial and/or vascular permeability for pro-inflammatory products243,245,246. In addition, infection with SARS-CoV-2 leads to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production243,247,248. These effects lead to lung fibrosis249, acute lung damage and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)9,250. ROS production and viral activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS)249,251 (via increased angiotensin II expression) cause insulin resistance39,252, hyperglycaemia253 and vascular endothelial damage243,254,255, all of which contribute to cardiovascular events, thromboembolism and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Infection also causes increases in the clotting components fibrinogen60,256 and D-dimer43,242,257, leading to increases in blood viscosity146,243 and vascular endothelial damage, and associated cardiovascular events, thromboembolism and DIC. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

COVID-19 and glucose metabolism

In human monocytes, elevated glucose levels directly increase SARS-CoV-2 replication, and glycolysis sustains SARS-CoV-2 replication via the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α20. Therefore, hyperglycaemia might support viral proliferation. In accord with this assumption, hyperglycaemia or a history of T1DM and T2DM were found to be independent predictors of morbidity and mortality in patients with SARS21. Furthermore, comorbid T2DM in mice infected with MERS-CoV resulted in a dysregulated immune response, leading to severe and extensive lung pathology22. Patients with diabetes mellitus typically fall into higher categories of SARS-CoV-2 infection severity than those without23,24, and poor glycaemic control predicts an increased need for medications and hospitalizations, and increased mortality18,25 (Table 1; Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus and COVID-19

| Region | Study design | Age (years; mean or median) | Number (women/men) | Glycaemic status, HbA1c (%) (proportion) | Comorbidities (%) | Main findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||||

| France | Nationwide observational cohort study | 69.8 ± 13.0 | 1,317 (462/855) | 8.1 ± 1.9 |

HTN (77) CVD (41) HF (12) CKD (33) COPD (10) |

Primary outcome (MV, death on day 7): 29% Risk factors for primary outcome: BMI Risk factors for mortality: older age, microvascular and macrovascular complications |

45 |

| China | Retrospective cohort study | 64.0 (56.2–72.0) | 153 |

<7.0 (16%) 7.0–8.0 (13%) 8.0–9.0 (12%) >9.0 (24%) |

HTN (57) CVD (21) CKD (4) COPD (5) |

ICU admission: 18% (non-DM 8%) In-hospital death: 20% (non-DM 11%) Risk factors for mortality: age ≥70 years, HTN |

211 |

| USA | Retrospective cohort study | 66.7 ± 14.2 | 178 (68/110) | 8.1 ± 2.0 |

HTN (75) CHD (25) HF (16) CKD (26) COPD (26) |

ICU admission: OR 1.59 (95% CI 1.01–2.52)a MV: OR 1.97 (95% CI 1.21–3.20)a Mortality: OR 2.02 (95% CI 1.01–4.03)a |

212 |

| USA | Retrospective cohort study | 67.9 ± 13.7 | 1,276 (649/630) | 7.5 ± 2.0 |

HTN (91) CVD (59) CKD (43) COPD (14) |

Death: 33% Risk factors for mortality: insulin treatment before admission, COPD, male sex, older age, higher BMI |

213 |

| T1DM | |||||||

| UK (England) | Population-based cohort study | 46.6 ± 19.6 | 264,390 (114,710/ 149,680) |

<6.5 (7%) 6.5–7.0 (8%) 7.1–9.9 (50%) ≥10.0 (12%) |

HTN (SBP >140 mmHg (17); antihypertensive agents (44)) CKD (10) MI (1) Stroke (1) HF (3) |

COVID-19-related deaths: 464 Risk factors for mortality: male sex, older age, renal impairment, non-white ethnicity, socioeconomic deprivation, previous stroke, previous HF, HbA1c ≥10.0% (reference range 6.5–7.0%) BMI (U-shaped, reference range 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) |

11 |

| UK (England) | Whole population study | 46.6 ± 19.5 | 263,830 (114,495/ 149,330) | No glycaemic data |

CHD (10) CeVD (4) HF (3) |

COVID-19-related deaths: 364 72-day mortality: 138 (95% CI 124−153) per 100,000 people Mortalitya: OR 3.51 (95% CI 3.16−3.90) |

19 |

| France | Nationwide observational cohort study | 56.0 ± 16.4 | 56 (25/31) | 8.4 (7.6–9.5) |

Microvascular complications (49) Macrovascular complications (33) CKD (29) COPD (4) |

Primary outcome (MV, death on day 7): 23% (age <55 years 12%; 55–74 years 24%; ≥75 years 50%) | 141 |

| T2DM | |||||||

| China | Retrospective cohort study | 62 (55–68) | 952 (442/510) | Glucose 8.3 mmol/l (6.2–12.4 mmol/l) |

HTN (53) CHD (14) CeVD (6) CKD (5) COPD (1) |

Well-controlled versus poorly controlled T2DM All-cause mortality: HR 0.14 (95% CI 0.03–0.60) ARDS: HR 0.47 (95% CI 0.27–0.83) Acute kidney injury: HR 0.12 (95% CI 0.01–0.96) Acute heart injury: HR 0.24 (95% CI 0.08–0.71) |

18 |

| UK (England) | Population-based cohort study | 67.5 ± 13.4 | 2,874,020 (1,267,590/ 1,606,430) |

<6.5 (25%) 6.5–7.0 (21%) 7.1–7.5 (13%) 7.6–9.9 (25%) ≥10.0 (11%) |

HTN (SBP >140 mmHg (67); antihypertensive agents (76)) CKD (18) MI (2) stroke (2) HF (5) |

COVID-19-related deaths: 10,525 Risk factors for mortality: male sex, older age, renal impairment, non-white ethnicity, socioeconomic deprivation, previous stroke, previous HF, HbA1c ≥7.5% or <6.5% (reference range 6.5%–7.0%), BMI (U-shaped, reference range 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) |

11 |

| UK (England) | Whole population study | 67.4 ± 13.4 | 2,864,670 (1,263,615/ 1,601,045) | No glycaemic data |

CHD (19) CeVD (7) HF (6) |

COVID-19-related deaths: 7,434 72-day mortality: 260 (95% CI 254−264) per 100,000 people Mortalityb: OR 2.03 (95% CI 1.97−2.09) |

19 |

| China | Retrospective cohort study | 63.0 (56.0–69.0) | 1,213 (632/581) | Glucose 8.6 (6.5–12.5) mmol/l |

CHD (15) HF (0.2) CeVD (4) |

Metformin versus non-metformin Acidosis: HR 2.73 (95% CI 1.04−7.13) Lactic acidosis: HR 4.46 (95% CI 1.11−18.00) Mortality: HR 1.65 (95% CI 0.71−3.86) ARDS: HR 0.85 (95% CI 0.61−1.17) DIC: HR 1.68 (95% CI 0.26−10.90) Acute kidney injury: HR 0.65 (95% CI 0.19−2.24) Acute heart injury: HR 1.02 (95% CI 0.62−1.66) |

214 |

Major studies are included; for a more comprehensive list of studies, please refer to Supplementary Table 1. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CeVD, cerebrovascular disease; CHD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; DM, diabetes mellitus; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; ICU, intensive care unit; MI, myocardial infarction; MV, mechanical ventilation; SBP, systolic blood pressure; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. aDM versus non-DM. bT2DM versus non-DM.

Of note, glycaemic deterioration is a typical complication of COVID-19 in patients with impaired glucose regulation or diabetes mellitus. For example, in patients requiring insulin, SARS-CoV infection was associated with a rapidly increasing need for high doses of insulin (often approaching or exceeding 100 IU per day)26. Changes in insulin needs are seemingly associated with the levels of inflammatory cytokines26,27. Although ketoacidosis is typically a problem closely associated with T1DM, in patients with COVID-19, ketoacidosis can also occur in those with T2DM. For example, in a systematic review, 77% of patients with COVID-19 who developed ketoacidosis had T2DM28.

Inflammation and insulin resistance

The most common post-mortem findings in the lungs of people with fatal COVID-19 are diffuse alveolar damage and inflammatory cell infiltration with prominent hyaline membranes29. Other critical findings include myocardial inflammation, lymphocyte infiltration in the liver, macrophage clustering in the brain, axonal injuries, microthrombi in glomeruli and focal pancreatitis29. These findings indicate an inflammatory pathology in COVID-19 (Fig. 1). In addition, an integrated analysis showed that patients with severe COVID-19 have a highly impaired interferon type I response with low IFNα activity in the blood, indicating high blood viral load, and an impaired inflammatory response30. It has also been reported that the inborn errors of type I interferon immunity related to TLR3 and IRF7 (ref.31), or B cell immunity32, underlie fatal COVID-19 pneumonia in 12.5% of men and 2.6% of women. The aforementioned findings indicate considerable variations in immune phenotypes among patients with COVID-19.

Some patients with severe COVID-19 experience a cytokine storm, which is a dangerous and potentially life-threatening event33,34. A retrospective study of 317 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 showed the presence of active inflammatory responses (IL-6 and lactate dehydrogenase) within 24 h of hospital admission, which were correlated with disease severity35. Furthermore, blood levels of IL-6 and lactate dehydrogenase are independent predictors of COVID-19 severity35. Of note, IL-6 has pro-inflammatory properties in innate immunity, and its levels can correlate with both the degree of disease severity and with a procoagulant profile36. Through increasing oxidative stress, IL-6 can damage proteins, lipids and DNA, and impair the body’s structure and function, and we propose that this effect might lead to rapid progression of COVID-19 in patients with diabetes mellitus (Fig. 1). Notably, a systems biological assessment of immunity in patients with severe COVID-19 showed increased levels of bacterial DNA and lipopolysaccharide in the plasma37, which were positively correlated with the plasma levels of IL-6 as well as EN-RAGE, a biomarker of pulmonary injury that is implicated in the pathogenesis of sepsis-induced ARDS38. These findings suggest a role for bacterial products, perhaps of lung origin, in augmenting the production of inflammatory cytokines in severe COVID-19.

Several mechanisms have been proposed by which virally induced inflammation increases insulin resistance39. For example, in coronavirus-induced pneumonia, such as SARS and MERS, inflammatory cells infiltrate the lungs, leading to acute lung injury, ARDS and/or death40. This large burden of inflammatory cells can affect the functions of skeletal muscle and the liver, the major insulin-responsive organs that are responsible for the bulk of insulin-mediated glucose uptake41. In addition, patients with severe COVID-19 show muscle weakness and elevation of liver enzyme activities, which might suggest multiple organ failure, particularly during a cytokine storm42.

COVID-19 can progress to ARDS, which requires positive pressure oxygen and intensive care therapy9. ARDS is characterized by severe oedema of the alveolar wall and lung parenchyma, accompanied by a marked rise in inflammatory parameters, such as C-reactive protein levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rates. Patients with COVID-19 also exhibit elevation of other inflammatory markers, such as D-dimer, ferritin and IL-6 (ref.43), which might contribute to an increased risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications originating from low-grade vascular inflammation in patients with underlying diabetes mellitus44. In a nationwide study in France, microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes mellitus were significantly associated with increased risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19 (ref.45). Whether COVID-19 accelerates the progression of diabetic complications needs to be studied. Thus, the molecular pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 is related to oxidative stress and inflammation, which can contribute to sepsis progression (Fig. 1).

Immunomodulation

It is recognized that mechanisms linking COVID-19 and both T1DM and T2DM overlap with pathways that regulate immune function16. For example, age is the strongest risk factor for developing T2DM and the effect of ageing on immune function might be equally important for COVID-19 susceptibility and severity. Hyperglycaemia can affect immune function; conversely, a dysregulated immunological status is linked to macrovascular complications of diabetes mellitus46,47. Thus, T2DM is associated with immunological dysregulation, which is potentially equivalent to accelerated ageing, and could therefore potentially explain the poor prognosis in patients with diabetes mellitus and COVID-19 (Fig. 1).

In individuals with obesity, pro-inflammatory cytokines with a T helper type 1 cell signature are known to increase insulin resistance48; however, the role of such cytokines in COVID-19 is unclear. Whether and how SARS-CoV-2 infection induces loss of glycaemic control in patients who are at risk of developing diabetes mellitus is also unclear. One study demonstrated that acute respiratory virus infection increases IFNγ production, and it causes muscle insulin resistance in humans, which drives compensatory hyperinsulinaemia to maintain euglycaemia and to boost antiviral CD8+ T cell responses39. It can be hypothesized that in patients with impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes mellitus, such compensation might fail49. Of note, hyperinsulinaemia can increase antiviral immunity through direct stimulation of CD8+ effector T cell function39. In prediabetic mice with hepatic insulin resistance caused by diet-induced obesity, murine cytomegalovirus infection resulted in a deterioration of glycaemic control39. Thus, during SARS-CoV-2 infection, the ensuing antiviral immune and inflammatory responses can change insulin sensitivity, potentially aggravating impairments of glucose metabolism (Fig. 1).

Interestingly, respiratory syncytial viruses increase the production of IFNγ, which activates natural killer (NK) cells as a defensive mechanism50. Both increased production of IFNγ and activated NK cells exacerbate systemic inflammation in muscle and adipose tissues, overall establishing a detrimental effect on glucose uptake51. Furthermore, a relationship exists between NK cell activity and glucose control in patients with impaired glucose metabolism. For example, NK cell activity was lower in patients with T2DM than in those with prediabetes or normal glucose tolerance52. In addition, multiple regression analysis showed that the HbA1c level is an independent predictor of NK cell activity in patients with T2DM52. Thus, individuals with impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes mellitus have reduced NK cell activity, which might help to explain why patients with diabetes mellitus are more susceptible to COVID-19 and have a worse prognosis than those without diabetes mellitus. In summary, understanding the immunomodulation occurring during SARS-CoV-2 infection is crucial for identifying therapeutic targets and developing effective medications as well as understanding its pathogenesis.

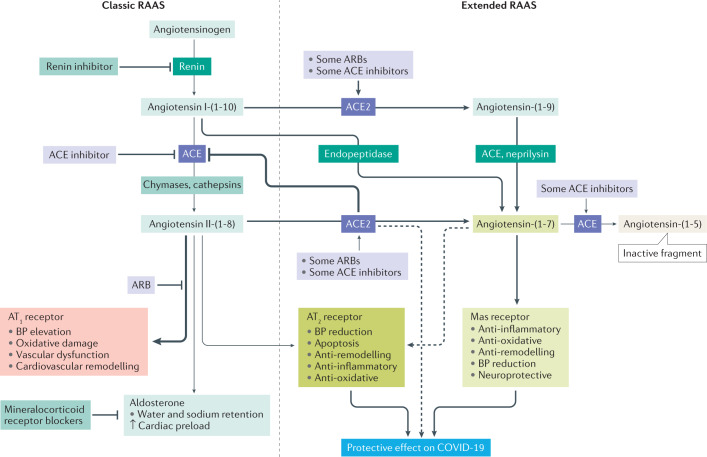

Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

As a part of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) (Fig. 1), ACE2 has already received much attention as it can also serve as an entry receptor for SARS-CoV as well as SARS-CoV-2 (ref.53). ACE2 was initially reported to be predominantly expressed in the respiratory system53. However, a more sophisticated study using immunohistochemical analyses found that ACE2 is expressed mainly in the intestines, kidneys, myocardium, vasculature and pancreas, but expression is limited in the respiratory system54. Evidence therefore suggests that ACE2 is expressed in many human cells and tissues, including pancreatic islets55. Studies using samples from patients with COVID-19 are warranted to investigate the colocalization of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 and help in understanding the progression of COVID-19 and the viral pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2.

Some evidence suggests an association between ACE2 and glucose regulation. For example, Ace2-knockout mice have been found to be more susceptible than wild-type mice to high-fat diet-induced pancreatic β-cell dysfunction56. Furthermore, infection with SARS-CoV can cause hyperglycaemia in people without pre-existing diabetes mellitus57. This finding and the localization of ACE2 expression in the endocrine pancreas together suggest that coronaviruses might specifically damages islets, potentially leading to hyperglycaemia57. Of note, hyperglycaemia was seen to persist for 3 years after recovery from SARS, perhaps indicating long-term damage to pancreatic β-cells57. These data suggest that the ACE2 as part of the RAAS might be involved in the association between COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The role of ACE2 within the RAAS.

Because angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is considered an important severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) receptor facilitating infection of relevant cells, such as pneumocytes, it is important to understand its normal physiological function. Inhibition of ACE blocks metabolism of angiotensin-(1–7) to angiotensin-(1–5) and can lead to elevation of angiotensin-(1–7) levels in plasma and tissues258. In animal models, angiotensin-(1–7) enhances vasodilation and inhibits vascular contractions to angiotensin II258. An ex vivo study using human internal mammary arteries showed that angiotensin-(1–7) blocks angiotensin II-induced vasoconstriction and inhibits ACE in human cardiovascular tissues258. In an ex vivo study, angiotensin-(1–7) and some ACE inhibitors, such as quinaprilat and captopril, potentiated bradykinin, resulting in blood pressure reduction by inhibiting ACE259. Thus, angiotensin-(1–7) acts as an ACE inhibitor and might stimulate bradykinin release259. These results show that angiotensin-(1–7) might be an important modulator of the human renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS). ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; AT1, angiotensin type 1; AT2, angiotensin type 2; BP, blood pressure.

Increased COVID-19 severity

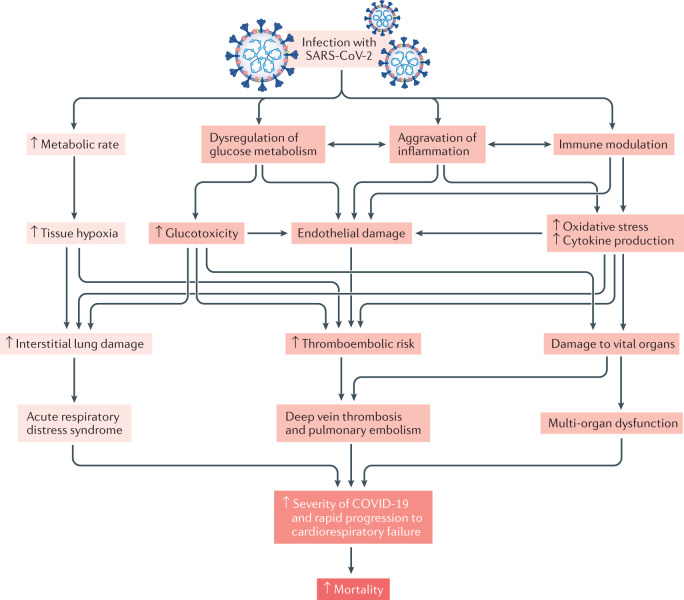

Two early case series of critically ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs in the USA found diabetes mellitus prevalence of 58% and 33%58,59, suggesting a link between severe COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus. Several mechanisms are thought to be responsible for an accentuated clinical severity of COVID-19 in people with diabetes mellitus (Fig. 3). As described already, glucotoxicity, endothelial damage by inflammation, oxidative stress and cytokine production contribute to an increased risk of thromboembolic complications and of damage to vital organs in patients with diabetes mellitus60 (Fig. 1). In addition, drugs often used in the clinical care of patients with COVID-19, such as systemic corticosteroids or antiviral agents, might contribute to worsening hyperglycaemia (Table 2; Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 3. Potential accentuated clinical processes after SARS-CoV-2 infection in people with diabetes mellitus.

Darker red indicates processes that are accentuated in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection increases metabolic rate, resulting in tissue hypoxia, which induces interstitial lung damage and acute respiratory distress syndrome9,250. Patients with diabetes mellitus and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) exhibit dysregulation of glucose homeostasis, aggravation of inflammation and impairment in the function of the immune system9,43,242,243. These conditions increase oxidative stress243,247,248, cytokine production and endothelial dysfunction243,254,255, leading to increased risk of thromboembolism and damage to vital organs. All these factors contribute to increased severity of COVID-19 and rapid progression to cardiorespiratory failure in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Table 2.

Glycaemic effects of potential pharmacological agents for COVID-19

| Drugs | Mechanisms of action | Source of data | Blood glucose | Insulin sensitivity or resistance | β-Cell function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camostat mesylate | Serine protease (TMPRSS2) inhibitor | Human studies | ↓ Patients with new-onset DM and chronic pancreatitis172 | – | – |

| Animal studies | ↓ BG175; ↓ PPG215 | ↓ Insulin level173; ↓ insulin resistance175 | ↓ Insulin secretion (reversed by GIP)216,217 | ||

| Cells/organs | ↓ BG176 | ↓ Insulin level174 | – | ||

| Patients with DM and/or insulin resistance | ↓ BG175; ↓ PPG215 | ↓ Insulin level173, ↓ insulin resistance175 | – | ||

| Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine | Blockade of virus entry and immunomodulation | Human studies | ↓ HbA1c (refs178,180,218); ↓ FPG178; ↓ PPG or BG180; ↓ hazard ratio for incident new-onset DM by 38% in patients with RA219; hypoglycaemia180,181 | ↑ Insulin sensitivity178; ↑ hepatic insulin sensitivity220 | ↑ β-Cell function178 |

| Cells/organs | – | – | GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake: ↓ in adipocytes221, ↑ in muscle cells222 | ||

| Patients with DM and/or insulin resistance | ↓ HbA1c (refs178,180,218); ↓ FPG178; ↓ PPG or BG180; ↓ hazard ratio for incident new-onset DM by 38% in patients with RA219; hypoglycaemia180,181 | – | – | ||

| Protease inhibitors | Proteolytic processing of viral proteins | Human studies | ↑ FPG185; ↑ BG186,223; ↑ in patients with new-onset DM187 | ↑ Insulin level185,223,224; ↓ insulin sensitivity185,223,224; ↓ glucose clearance185; ↓ non-oxidative glucose disposal224,225 | ↓ β-Cell function185; ↓ first-phase insulin release185 |

| Animal studies | – | – | ↓ GLUT4 activity226,227 | ||

| Cells/organs | – | – | ↓ GLUT4 activity228 or mRNA229 | ||

| RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors | Inhibition of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | Animal studies | ↓ FPG191 | ↓ Insulin level191; ↓ insulin resistance193 | – |

| Patients with DM and/or insulin resistance | ↓ FPG191 | ↓ Insulin level191; ↓ insulin resistance193 | – | ||

| IL-6 receptor inhibitors | IL-6 antagonism, suppressing the production of inflammatory molecules | Human studies | ↓ HbA1c (ref.230) | ↓ Insulin level194; ↓ insulin-to-glucose ratio194; ↑ insulin sensitivity194; ↓ insulin resistance194 | – |

| Animal studies | ↓ Glucose intolerance231 | – | – | ||

| Cells/organs | – | – | ↓ Transplanted islet cell death231 | ||

| Patients with DM and/or insulin resistance | ↓ HbA1c (ref.230); ↓ glucose intolerance231 | – | ↓ Transplanted islet cell death231 | ||

| IL-1 receptor inhibitors | IL-1 antagonism | Human studies | ↓ HbA1c (refs196,232); ↓ FPG232; no effect on HbA1c and BG in patients with recent-onset T1DM198 | ↑ C-peptide secretion196; ↑ proinsulin-to-insulin ratio196 | – |

| Animal studies | ↓ Glucose intolerance231 | – | – | ||

| Cells/organs | – | – | ↑ Insulin secretion in transplanted islets231; ↓ transplanted islet cell death231 | ||

| Patients with DM and/or insulin resistance | ↓ HbA1c (ref.232); ↓ FPG232; no effect on HbA1c and BG in patients with recent-onset T1DM198 | No effect on C-peptide secretion in patients with T1DM198 | ↑ Insulin secretion in transplanted islets231; ↓ transplanted islet cell death231 | ||

| IL-1β inhibitors | IL-1β antagonism | Human studies | No effect on HbA1c in patients with recent-onset T1DM198 | No effect on C-peptide secretion in patients with recent-onset T1DM198 | – |

| Patients with DM and/or insulin resistance | No effect on HbA1c in patients with recent-onset T1DM198 | No effect on C-peptide secretion in patients with recent-onset T1DM198 | – | ||

| JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors | Suppressing JAK–STAT signalling, inhibition of clathrin-medicated endocytosis, immunosuppression | Animal studies | ↓ Reversal of new-onset DM in NOD mice200 | ↓ Insulin level233 | – |

| Patients with DM and/or insulin resistance | ↓ DM development200 | ↓ Insulin level233 | – | ||

| BTK inhibitor | Immunomodulatory effect on macrophages, reducing the production of cytokines | Animal studies | ↓ BG201 | – | – |

| TNF inhibitors | TNF antagonism | Human studies | ↓ FBG205,234,235; ↓ HbA1c (refs230,235); ↓ patients with new-onset DM and RA and psoriasis236 | ↓ Insulin resistance205,235,237; ↑ insulin sensitivity205,237 | ↑ β-Cell function205 |

| Patients with DM and/or insulin resistance | ↓ FBG205,234,235; ↓ HbA1c (refs230,235) | ↓ Insulin resistance205; ↑ insulin sensitivity205 | ↑ β-Cell function205 | ||

| Corticosteroids206,238 | Anti-inflammatory effects | Human studies | ↑ HbA1c; ↑ BG (mainly PPG) | ↑ Insulin resistance; ↓ insulin sensitivity | ↓ Insulin production and secretion |

BG, blood glucose; BTK, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 19; DM, diabetes mellitus; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GIP, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide; GLUT4, glucose transporter type 4; JAK, Janus kinase; NOD, non-obese diabetic; PPG, postprandial glucose; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease serine 2; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

A multicentre retrospective study from China found that high fasting glucose levels (≥7.0 mmol/l (≥126 mg/dl)) at admission was an independent predictor of increased mortality in patients with COVID-19 who did not have diabetes mellitus61. Therefore, it is prudent to monitor glucose levels and to treat worsening hyperglycaemia in patients with progression to severe states of COVID-19.

Of note, a study found that therapy with the corticosteroid dexamethasone reduced mortality in patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation by 36% (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.51–0.81) and in those receiving oxygen only by 18% (HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.72–0.94)62. Whether similar benefits were observed in the 24% of participants with diabetes mellitus has not yet been reported. Glucocorticoid therapy probably reduces production of cytokines and prevents their detrimental effects in patients with severe COVID-19. Further long-term studies are required to confirm this result, particularly in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Glucose-lowering drugs

Glucose-lowering medications commonly used to treat diabetes mellitus might have effects on COVID-19 pathogenesis, and these effects could have implications for the management of patients with diabetes mellitus and COVID-19.

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4

Also known as CD26, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) is well recognized to have an important function in glucose homeostasis63. In addition, DPP4 has an integral role in the immune system as a marker of activated T lymphocytes and a regulator of the expression of many chemokines, including CCL5, CXCL12, CXCL2 (also known as GRO-b) and CXCL11 (also known as I-TAC)64,65. DDP4 inhibitors (DPP4is) are commonly used to decrease blood levels of glucose and to treat T2DM.

Based on reports of upper respiratory tract infections, concerns have been raised about an increased risk of viral infections with DPP4 inhibition66; however, evidence from clinical trials on the association between the use of DPP4is and the risk of community-acquired pneumonia in patients with T2DM does not confirm an increased risk67. Although ACE2 is recognized as the main receptor, DPP4 might also bind to SARS-CoV-2 (ref.68). Interestingly, certain polymorphisms of the DPP4 protein found in people in Africa were associated with a reduced chance of MERS-CoV infection69. However, plasma levels of DPP4 in patients with MERS-CoV were statistically significantly reduced70, suggesting a protective role of DPP4. Whether DPP4is affect the function of DPP4 as a viral receptor is a matter of debate.

The expression of DPP4 in the spleen, lung, liver, kidney and some immune cells seems to be altered in patients with T2DM71. Furthermore, DPP4 is not just a cell membrane protein but is shed into the circulation as soluble DPP4. Of note, levels of soluble DPP4 are increased by DPP4is in mice72. Whether soluble DPP4 might have a role as a virus receptor or is protective during SARS-CoV-2 infection is entirely unclear. In an in vitro study, treatment with the DPP4is sitagliptin, vildagliptin or saxagliptin did not block the entry of coronaviruses into cells73. More detailed studies are needed to fully characterize the role of DPP4is in patients with COVID-19 and T2DM.

Interactions between DPP4 and the RAAS (including ACE2) have not been studied in detail but seem possible74,75. DPP4 and the RAAS are linked genetically and are associated with the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and possibly severity of COVID-19, particularly in patients with diabetes mellitus76. This link is supported by the findings that DPP4 expression was increased in blood T lymphocytes from patients with T2DM and was correlated with insulin resistance77, and upregulation of DPP4 in diabetic animals led to dysregulation of immune responses78.

Therapy with DPP4is proved neutral, not superior, in terms of major adverse cardiac events, including stroke, in previous DPP4i cardiovascular outcome trials in patients with T2DM79,80; however, DPP4 inhibition has been reported to have beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system, such as reducing oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress, because of its anti-inflammatory properties63,81. More specifically, the receptor binding domain of DPP4 interacts with adenosine deaminase (ADA) in CD4+ and CD8+ human T cells82,83. This finding indicates a possible modulation of the host’s immune system by SARS-CoV-2, through binding to DPP4 and competing for the ADA recognition site. Thus, the DPP4 receptor binding domain might represent a potential strategy for treating infection by SARS-CoV-2 (ref.84).

Of note, a study found that systemic DPP4 inhibition with DPP4is increased circulating levels of inflammatory markers in a mouse model fed with regular chow85. By contrast, in humans, treatment with a DPP4i decreased DPP4 enzyme activity but did not increase the levels of inflammatory markers85. These findings suggest the possibility of dissociation between DPP4 enzyme activity, the use of DPP4i and inflammatory markers in animals and humans. Moreover, DPP4i treatment suppressed T cell immune responses to the virus in an experiment in human peripheral blood86. One human study found that circulating levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor were decreased by DPP4 inhibition87. Clearly, the effect of DPP4 inhibition on T cell function and T cell-mediated inflammatory and immune responses in patients with COVID-19 requires further research.

Current knowledge does not suggest safety issues associated with the use of DPP4is in patients with T2DM and COVID-19 (refs45,88). In a retrospective case–control study from northern Italy, sitagliptin treatment during hospitalization was associated with reduced mortality and improved clinical outcomes in such patients89. Another Italian case series described the association between DPP4i treatment and a statistically significantly reduced mortality; however, this result was based on only 11 patients (of whom one died)90. However, DPP4i treatment was associated with worse outcomes (mortality results were not presented) in 27 patients with T2DM treated with DPP4is than in 49 treated with other glucose-lowering medications87. Therefore, prospective randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in diverse populations of patients with T2DM and COVID-19 are necessary to assess the potential survival benefits associated with DPP4 inhibition in patients with COVID-19, which might also extend to patients without diabetes mellitus.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 and its analogues

Therapy with most glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) analogues in patients with T2DM reduced the rate of major adverse cardiac events in cardiovascular outcome trials79,91. GLP1 contributes to glucose homeostasis and GLP1 receptor stimulation elicits a variety of pleiotropic effects (for example, on immune function92 and inflammatory processes93). In humans, GLP1 receptors are widely distributed in various cells and organs, including the kidneys, lungs, heart, endothelial cells and nerve cells91. GLP1-based treatments reduce the production of various inflammatory cytokines and infiltration of immune cells in the liver, kidney, lung, brain and the cardiovascular system63,91,94.

In animal models of atherosclerosis, the GLP1 analogue exendin 4 substantially reduced the accumulation of monocytes and macrophages in the vascular wall and inhibited atherogenesis by regulating inflammation in macrophages95. In addition, exendin 4 exerted renoprotective effects in animal models through inhibition of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity in the kidney, and elevated NF-κB activity is known to contribute to the crosstalk between inflammation and oxidative stress96. In vitro, liraglutide treatment reduced expression of the vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 in human aortic endothelial cells after stimulation with lipopolysaccharide or tumour necrosis factor97. In addition, liraglutide administered to C57BL/6 mice fed a high-fat diet reduced inflammation and lipid accumulation in the heart98.

Infusions of native GLP1 in patients with T1DM reduced plasma levels of IL-6, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and markers of oxidative stress99. In humans, GLP1 and GLP1 analogues have been shown to be beneficial for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, atherosclerosis and neurodegenerative disorders100,101 and these effects seem to be primarily mediated by a reduction in the activity of inflammatory pathways91. Whether such effects on the low-grade inflammation associated with atherosclerosis translate into anti-inflammatory effects relevant for the disease process of COVID-19 remains to be studied. However, there is little concern for the continued use of GLP1 analogues in patients with diabetes mellitus and COVID-19 based on such properties.

People with CVD or kidney disease show a worse prognosis during the course of COVID-19 than those without these diseases43. Therefore, it seems to be prudent to preserve the integrity of the cardiorenal system in people at high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Given that beneficial roles of GLP1 analogues for the prevention of CVD and kidney disease have been well established80,102, these drugs could be an ideal option for the treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus at such risk103.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, having overweight or obesity has several disadvantages; for example, the presence of chronic low-grade inflammation and a compromised immune system104. People with COVID-19 and obesity showed lower lung compliance and worse health outcomes than those with COVID-19 but without obesity, and health-care providers have difficulties in finding the right mask size and problems with mask ventilation104. Therefore, GLP1 analogues can be recommended for patients with obesity and T2DM because they have weight-reducing properties105. However, initiating or maintaining such therapies in acute or critical situations (such as severe COVID-19) is not recommended because they will take time to become effective, due to slow up-titration, and might provoke nausea and vomiting106.

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors (SGLT2is) act on the kidney to reduce blood levels of glucose and are used to treat T2DM. In patients with T2DM, treatment with SGLT2is reduced infiltration of inflammatory cells into arterial plaques107 and decreased the mRNA expression levels of some cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF, IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1)108. However, SGLT2i treatment can cause ketoacidosis109, especially in critically ill patients. Importantly, SGLT2is have profound effects on urinary glucose and sodium excretion, resulting in osmotic diuresis and potentially dehydration109, and increased urinary uric acid excretion, which has been suggested to be a risk factor for acute kidney injury through both urate crystal-dependent and crystal-independent mechanisms110. As such, the use of SGLT2is might be difficult in patients under critical care, who need meticulous control of their fluid balance. In addition, these drugs must be discontinued in the face of a reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate, which limits their glucose-lowering effects substantially, and will be a typical risk in critically ill patients. Nonetheless, an international study is ongoing to evaluate the effect of dapagliflozin versus placebo, given once daily for 30 days, in reducing disease progression, complications and all-cause mortality in all patients admitted with COVID-19 (NCT04350593). The result of this study might help reveal the implications of the use of SGLT2is in such patients.

Thiazolidinedione

The thiazolidinediones are agonists of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), a nuclear receptor that regulates the transcription of various genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism111. In many basic and animal studies, thiazolidinediones have been found to reduce insulin resistance and to have putative anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, contributing to their anti-atherosclerotic properties112,113. Given these properties, thiazolidinediones have the potential to mediate protective effects on the cardiovascular system. In a review of RCTs that compared thiazolidinediones with placebo for the secondary prevention of stroke and related vascular events in people who had experienced stroke or transient ischaemic attack, thiazolidinedione treatment reduced the recurrence of stroke compared with placebo114. However, thiazolidinedione therapy was associated with weight gain and oedema and more importantly was associated with aggravation of heart failure115. These results do not support the use of thiazolidinedione in patients with COVID-19. More clinical trials are needed to optimize the risk–benefit ratio of using thiazolidinediones in patients with COVID-19.

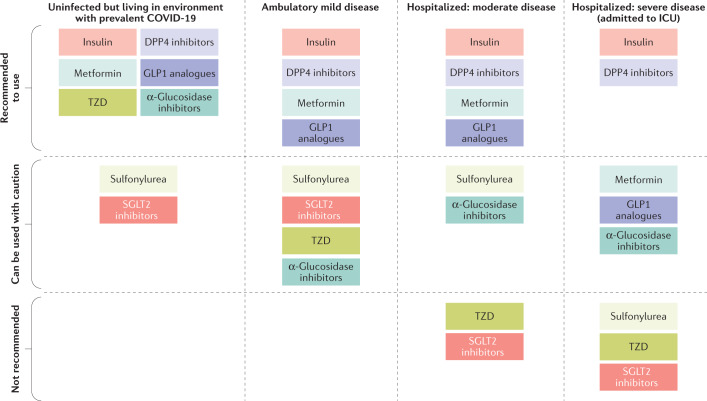

Use of antidiabetic medications

Based on the data from previous basic and clinical studies and the most recent information available from current publications, we propose some guidelines for the use of glucose-lowering medications in patients with T2DM and COVID-19, according to the clinical status of COVID-19, which is based on the WHO clinical progression scale116 (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table 3). Few published recommendations exist for the use of these medications during the COVID-19 pandemic16. In patients with COVID-19, we should be prepared for acute hyperglycaemia (that might be exacerbated by inflammation-associated insulin resistance), and we face the need to provide appropriate glycaemic control effectively and rapidly. The choice of agents should be guided mainly by their presumed effectiveness and by potential or actual adverse effects. In line with the review by Drucker16, we recommend DPP4is and GLP1 analogues in patients with mild to moderate symptoms because these agents have proven glucose-lowering efficacy in hospital settings, as well as in outpatient clinics. However, insufficient data are available to support the use of these agents instead of insulin in critically ill patients with T2DM and COVID-19, especially if the therapy needs to be initiated under conditions of severe illness (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table 3). The anti-inflammatory actions of DPP4is and GLP1 analogues suggest the need for clinical trials with such agents in patients with T2DM and COVID-19.

Fig. 4. Use of antidiabetic medications in patients with T2DM and COVID-19.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity is based on the WHO clinical progression scale116. Insulin is mainly recommended for critically ill patients with diabetes mellitus infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Optimal glucose control using insulin infusion statistically significantly reduced inflammatory cytokines and improved severity of COVID-19 (ref.117). Metformin can be used for uninfected patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) or ambulatory patients with mild COVID-19. However, it should be noted that metformin is not encouraged for use in critically ill patients. Sulfonylurea can be used in uninfected patients with T2DM, but it is not recommended in patients with severe COVID-19 because it can provoke hypoglycaemia. Thiazolidinediones have the potential to mediate protective effects on the cardiovascular system114. However, thiazolidinedione therapy induces weight gain and oedema and tends to aggravate heart failure115. These results do not support its use in patients with severe COVID-19. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) inhibitors are one of the most frequently prescribed medications without serious adverse events. DPP4 inhibitor therapy has proved neutral in terms of major adverse cardiac events in previous cardiovascular outcome trials79,80. Therefore, DPP4 inhibitors can be recommended for use in most patients with a broad spectrum of severity of COVID-19. Given that beneficial roles of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) analogues for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and kidney disease are well established80,102, these drugs could be an ideal option for the treatment of patients with T2DM at risk of CVD and kidney disease103. Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor treatment induces osmotic diuresis and potentially dehydration109, which has been suggested to be a risk factor for acute kidney injury and ketoacidosis110. As such, the use of SGLT2 inhibitors is not recommended in patients under critical care. ICU, intensive care unit; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

In line with Drucker’s recommendation16, we suggest using mainly insulin for critically ill patients with diabetes mellitus infected with SARS-CoV-2. Optimal glucose control using insulin infusion statistically significantly reduced IL-6 and D-dimer levels and improved severity in patients with COVID-19 with or without diabetes mellitus117. Metformin has shown anti-inflammatory actions in preclinical studies, and furthermore metformin treatment reduced the circulating levels of inflammation biomarkers in people with T2DM118. In a study that compared the outcomes in hospitalized Chinese patients with COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus (mean age 64 years, 53% men) between 104 patients receiving metformin and 179 patients not receiving metformin, in-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the those receiving metformin (2.9% versus 12.3%; P = 0.01)119; however, this finding might have been driven by selection bias, as patients with severe respiratory problems cannot be treated with metformin. Therefore, physicians should be conservative in their prescription of glucose-lowering medications, with the above considerations in mind, because there is little evidence proving superiority in the efficacy and safety of any specific medication in patients with diabetes mellitus and COVID-19.

Specific recommendations for the treatment of ketoacidosis in patients with COVID-19 have been published120, with an emphasis on subcutaneous insulin regimens. Frequent blood glucose and ketone body monitoring is mandatory in patients with COVID-19 and hyperglycaemia. Fluid and electrolyte management in patients with COVID-19 and impaired respiratory function should follow general recommendations121,122; no specific guidance exists for fluid and electrolyte management in patients with diabetes mellitus and COVID-19.

COVID-19 and T1DM

So far, information regarding the effect of diabetes mellitus on COVID-19 often has not differentiated between the major types123 and is mostly related to T2DM owing to the high prevalence of this form of diabetes mellitus11,19. Some important information is available specifically for T1DM, as discussed in this section.

Newly diagnosed T1DM

Case reports have described patients with newly diagnosed T1DM with ketoacidosis occurring at the onset of COVID-19 (ref.124), and patients with newly diagnosed T1DM without ketoacidosis in whom ketoacidosis occurred several weeks after apparent recovery from COVID-19 (ref.125). These findings raise the question as to whether SARS-CoV-2 can trigger this metabolic disease. One series found 29 patients who were not known to have diabetes mellitus who developed hyperglycaemia during treatment for COVID-19, some of whom had a normal HbA1c level on admission126. However, fewer paediatric patients with T1DM than expected were admitted to specialized Italian diabetes centres127. By contrast, specialized hospitals in northwest London, UK, saw more patients presenting with severe ketoacidosis than expected, suggesting a potential increase in numbers of patients with new-onset T1DM128. These contradictory findings might be explained by the small patient numbers analysed: they could have been down to chance, or they could be caused by changes in the availability of medical services during the COVID-19 pandemic. A population-based study from Germany found no deviation from the projected numbers of newly diagnosed paediatric patients with T1DM129. However, the same study found a statistically significant increase in diabetic ketoacidosis and severe ketoacidosis in children and adolescents presenting with new-onset T1DM130. A probable explanation is that this finding reflects patients trying to delay hospital admission because of their fear of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection. As the COVID-19 pandemic progresses and larger numbers of patients are studied, it will become more apparent if a true link exists between COVID-19 and new-onset T1DM.

Metabolic control of outpatients with T1DM

Several groups from Italy, Spain and the UK have reported that patients with T1DM and without COVID-19 have shown no deteriorations in glycaemic control, and often even show improvements in control, during the pandemic compared with a control period before the pandemic131–133. During lockdown, self-reported physical activity was found to be reduced133,134 and more consistent patterns of nutrient intake and sleep were found133; these findings might reflect conditions under which glycaemic control is easier to achieve. This effect might differ from the situation in developing countries with reduced access to food, medications, blood glucose test strips and medical services135,136. The COVID-19 pandemic has also offered opportunities for remote consultation and telemedicine, which might contribute to the glycaemic control patterns seen in developed countries137,138.

Hospitalized patients with T1DM and COVID-19

A population-based analysis from Belgium showed a similar risk of hospitalization in people with T1DM than in normoglycaemic individuals (0.21% versus 0.17%)139. In this study and another from the USA, hospitalized patients with T1DM being treated for COVID-19 had metabolic characteristics similar to patients with T1DM who were hospitalized owing to other diagnoses, and the levels of HbA1c were not higher in the patients with COVID-19 (refs139,140). However, plasma concentrations of glucose were higher at the time of admission in patients with T1DM and COVID-19 than in patients without non-COVID-19 diagnoses, indicating some acute deterioration in glycaemic control139. Worse outcomes in patients with T1DM and COVID-19 (defined as tracheal intubation or death up to day 7 of hospital treatment) seemed to be confined to patients aged ≥75 years141.

T1DM and COVID-19 outcomes

Two population-based analyses from the UK clearly indicated a higher mortality in patients with T1DM compared with a population without T1DM11,19. Patients with T1DM at particular risk were older, had increased HbA1c levels, arterial hypertension, renal functional impairment and previous cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke or heart failure)11,19. These data support the association between T1DM and poor COVID-19 outcomes.

RAAS inhibitors and statins

There have been relevant debates regarding benefits or harms related to the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to classic RAAS, alternative components, including ACE2, angiotensin-(1–7), angiotensin-(1–9) and the Mas receptor, might be involved in the entry and progression of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2). Many international medical societies recommend continuing RAAS inhibitors because there is no proven harm in using them in the context of diabetes mellitus and COVID-19.

The anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory effects of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors, or statins, suggest that they might be beneficial for treating influenza and bacterial infections142,143. A study from China found that statin use was associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality and a favourable recovery profile in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (ref.144). However, the benefit associated with statin therapy needs to be validated in RCTs. More information about the RAAS system, including ACE2 and statins, is presented in the Supplementary Box.

Thromboembolic events

Evidence suggests that COVID-19 considerably increases the likelihood of thromboembolic events, which represent a predominant cause of death6,145,146. The first evidence of abnormal coagulation parameters associated with COVID-19 appeared in early reports from China. For example, the baseline characteristics of the first 99 patients hospitalized in Wuhan found that 6% had an elevated activated partial thromboplastin time, 5% showed elevated prothrombin and 36% had elevated D-dimer6. Another study from China found that patients who died from COVID-19 had statistically significantly increased levels of D-dimer and fibrin degradation products60. In this study that included middle-aged Chinese patients with COVID-19, more than 71% of those who died fulfilled the criteria for disseminated intravascular coagulation, but only 0.6% of the survivors belonged in this category60. Of note, 11 studies thus far have found high rates of venous thromboembolism in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 (ref.147).

COVID-19-associated coagulopathy ranges from mild alterations in laboratory test outcomes to disseminated intravascular coagulation with a predominant phenotype of thrombotic and/or multiple organ failure148. The profound inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to the development of coagulation abnormalities146. Vascular endothelial dysfunction seems to contribute to the pathophysiology of microcirculatory changes in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection149. Importantly, SARS-CoV-2 can enter and infect endothelial cells via the ACE2 receptor150, with viral replication causing inflammatory cell infiltration, endothelial cell apoptosis and microvascular prothrombotic effects151. Post-mortem examinations of patients who died with SARS-CoV-2 infection have demonstrated viral inclusions within endothelial cells and sequestered mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cellular infiltration, with evidence of endothelial apoptosis151. Thus, evidence suggests that an increased release of coagulation factors and dysregulation and destruction of the endothelial cells are the main mechanisms of the increase in thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19 (ref.148). Endothelial dysfunction might also explain reports of cerebrovascular complications in younger patients, and in patients with myocardial ischaemia and/or thromboembolic complications151,152.

Thromboembolic risk in patients with diabetes mellitus

Several publications have reported an increased thromboembolic risk among patients with diabetes mellitus outside the specific situation of SARS-CoV-2 infection. For example, a population-based study found that patients with T2DM exhibited an increased risk of venous thromboembolism compared with controls (HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.27–1.63)153. Furthermore, the risks of pulmonary embolism were greater in the patients with T2DM than in the controls (HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.22–1.90)153. Another study found that the incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) after total knee replacement was statistically significantly higher in patients with diabetes mellitus than in those without154. Diabetes mellitus was also found to be associated with an increase of more than twofold in the risk of ulcer formation after DVT155. Thus, patients with diabetes mellitus are already in a high-risk category for a thromboembolic event or stroke156,157.

To prevent such complications, patients with diabetes mellitus who are at risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection should try not to be sedentary for long periods, as regular physical activity is associated with decreased incidence of thromboembolism158. Instead, these individuals should try to engage in physical activity to improve blood circulation. Appropriate simple exercises for performance at home (ankle rotations and calf massage) are available and effective159 and should be recommended. Patients who experience pain in their legs, shortness of breath or chest pain must not hesitate to contact their physician owing to suspected thromboembolic complications.

Considering an increased thromboembolic risk among patients with diabetes mellitus153–157, we propose that physicians should consider prescribing antiplatelet or anticoagulating agents more actively in patients with diabetes mellitus to prevent thromboembolic events and their complications during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The precise molecular and cellular mechanisms behind the higher coagulability of blood among patients with COVID-19 is currently poorly understood and conventional prophylaxis does not seem to be always effective in the prevention of thromboembolism160. However, anticoagulant therapy (low molecular weight heparin) produced better prognoses in patients with severe COVID-19 at high thromboembolic risk, such as those with elevated D-dimer levels161. Therefore, it might be prudent to start anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19, even though it might not be necessary in patients with a mild course of the disease.

Although the evidence supporting any direct effects of GLP1 analogues on the risk of thromboembolism is limited, several animal studies have found that treatment with GLP1 analogues inhibits atheroma formation and stabilizes plaques in carotid arteries and aortic arches100,162. Administration of GLP1 in vitro decreased the expression of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and MCP1 and the translocation of NF-κB–p65, which are linked to a high risk of thromboembolism100. A cardiovascular outcome study found that therapy with dulaglutide, a long-acting GLP1 analogue, decreased the incidence of stroke in patients with T2DM163. Taken together, it would be beneficial in patients with diabetes mellitus to choose antidiabetic agents that might be able to decrease the risk of thromboembolic events.

Potential drug interactions

Potential interactions might occur between investigational drugs for COVID-19 and commonly administered oral anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents. A combination agent of lopinavir and ritonavir, two protease inhibitors, is used empirically for treating patients with COVID-19 in some countries, including China and India164,165. These protease inhibitors inhibit cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) enzyme metabolism, resulting in reduced levels of the active metabolite of the antiplatelet agent clopidogrel. By contrast, these protease inhibitors might increase the antiplatelet effects of ticagrelor by inhibiting its metabolism166. The anticoagulant vitamin K antagonists, such apixaban and betrixaban, require dose adjustment, which could be adversely affected by interactions with protease inhibitors. By contrast, the anticoagulant effects of edoxaban and rivaroxaban, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, can be increased substantially by lopinavir and ritonavir, discouraging concomitant administration with these drugs167. Therefore, care should be taken in prescribing drugs that might affect the activity of CYP3A4 because they might affect the effects of antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants that are metabolized through the CYP3A4 system168. Remdesivir is a nucleotide analogue inhibitor of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and has shown beneficial effects in shortening the time to recovery in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 in a preliminary study169. Remdesivir was found to have no significant interactions with antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants166,168. In general, no major drug–drug interactions are known to occur between investigational COVID-19 therapies and parenteral anticoagulants.

Taken together, it is reasonable to assess the risk of thromboembolism and to consider pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in patients with diabetes mellitus, especially if they have other thromboembolic risk factors or they are hospitalized with COVID-19 (ref.147).

COVID-19 treatments and metabolism

The global pandemic of COVID-19 has accelerated the race to find effective prevention and treatment for SARS-CoV-2 infection170. Currently, more than 1,800 clinical trials targeting viral entry and replication and immune responses to infection are ongoing; however, the efficacy of most drugs has not yet been proven (ClinicalTrials.gov database of COVID-19 interventional studies). Candidates for COVID-19 therapy can affect glucose metabolism pharmacologically or through the modulation of inflammation and the immune system (Table 2; Supplementary Table 2). Thus, these drugs require particular consideration in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Antiviral therapies

Camostat mesylate is a serine protease inhibitor being investigated for its ability to inhibit viral entry, as it inhibits transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), which facilitates viral entry into the host cell171. It was reported that camostat mesylate treatment reduced the incidence of new-onset diabetes mellitus in patients with chronic pancreatitis172. This drug improved glycaemia and insulin resistance and decreased lipid accumulation in animal models173,174. The antimalaria drugs chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have been used to treat SARS-CoV-2 infection despite their potential adverse effects175,176. The two main mechanisms of action of hydroxychloroquine are believed to be via its restriction of viral spike protein cleavage at the ACE2 binding site, and its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties177. Hydroxychloroquine also has glucose-lowering efficacy by increasing insulin sensitivity and improving pancreatic β-cell function178, which has enabled hydroxychloroquine to be prescribed as an antidiabetic medication in some countries179. Therefore, adjustment of pre-existing antidiabetic drugs might be needed to avoid hypoglycaemia in uncommon cases of patients with diabetes mellitus who are taking hydroxychloroquine180–182. Of note, studies have shown conflicting results in the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 (refs183,184). More well-designed studies are urgently needed to evaluate its therapeutic efficacy.

Protease inhibitors such as lopinavir and ritonavir have been reported to increase the risk of hyperglycaemia185,186 and new-onset diabetes mellitus187, to exacerbate pre-existing diabetes mellitus and occasionally to induce the development of diabetic ketoacidosis188. In patients with HIV infection, these drugs reduced insulin sensitivity and β-cell function by up to 50%185. Another issue with protease inhibitors is pharmacological interactions with co-administered glucose-lowering drugs. For example, ritonavir acts as an inhibitor of CYP3A4/5 (ref.189), increasing plasma concentrations of the DPP4i saxagliptin, and as an inducer of uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase190, decreasing concentrations of the SGLT2i canagliflozin. Therefore, frequent blood glucose monitoring and dosing adjustments are recommended for patients treated with these drug combinations. Remdesivir, a nucleotide analogue inhibitor of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, improved hyperglycaemia, insulin resistance, fatty liver and endotoxaemia in mice fed a high-fat diet191. By contrast, increases in blood levels of glucose were similar between the remdesivir-treated and placebo-treated groups in two RCTs with multiethnic groups169 and Chinese patients192. Thus, additional evidence is needed to elucidate its effect on glucose metabolism.

Adjunctive therapies

Adjunctive therapies are used to prevent the progression of COVID-19 to more severe forms, such as ARDS and multi-organ failure during the hyperinflammatory phase. However, these drugs can also influence glucose metabolism. For example, IL-6 receptor inhibitors, a possible therapeutic option in patients severely ill with COVID-19 who have extensive lung lesions and high IL-6 levels193, had beneficial effects on glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis194. Furthermore, anakinra, an IL-1β inhibitor that significantly improved respiratory function in patients with severe COVID-19 (ref.195), improved glycaemia and β-cell function in patients with T2DM196. By contrast, canakinumab, another IL-1β inhibitor that is under investigation in a clinical trial for the treatment of COVID-19 (ref.197), was not effective in the treatment of recent-onset T1DM198. In animal studies, Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitors and Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors, other investigational agents for COVID-19 treatment199, improved glycaemia200,201 and insulitis200 and impaired the levels of anti-insulin B lymphocytes202 and insulin antibodies203, which might have protective roles in T1DM. TNF inhibitors, particularly adalimumab, are promising therapeutic options for mitigating the inflammatory stage in COVID-19 (ref.204). The use of TNF inhibitors improved hyperglycaemia, insulin resistance and β-cell function in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis205.

Systemic corticosteroids are well known to induce hyperglycaemia, primarily by increasing postprandial levels of glucose, insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction206, that often necessitates the initiation of insulin therapy. Contrary to this concern, intravenous dexamethasone therapy statistically significantly increased the number of ventilator-free days among patients with severe ARDS and COVID-19 (refs62,207). Furthermore, a meta-analysis of clinical trials showed that systemic corticosteroid therapy is associated with reduced short-term all-cause mortality in patients with severe COVID-19 (ref.208). Hydrocortisone treatment in different regimens also showed a tendency to produce a better hospital course in these patients209. However, another study failed to prove any beneficial effect of low-dose hydrocortisone in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 (ref.210). The less than optimal dose might be a reason for these disappointing results. Further investigation is required to elucidate the effects of pharmacological treatments for COVID-19 on glucose metabolism in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Conclusions

During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with diabetes mellitus should be aware that COVID-19 can increase blood levels of glucose and, as such, they should follow clinical guidelines for the management of diabetes mellitus more strictly, as described here. We provide the following general guidance for patients and health-care providers: patients should be extra vigilant regarding their adherence to prescribed medications (including insulin injections) and their blood levels of glucose, which should be checked more frequently than previously. If blood concentrations of glucose are consistently higher than usual, patients should consult their physician. In the light of current global quarantine policies, more emphasis needs to be placed by health-care providers on healthy food intake and physical activity in patients with diabetes mellitus. If patients experience symptoms such as a dry cough, excessive sputum production or fever, or show a sudden rise in glucose level, they should be advised to consult their physician immediately. Furthermore, it is strongly recommended that patients should strictly adhere to the recommendations of their doctor and be wary of messages communicated by various types of media (including the internet), which often might not stand scientific scrutiny. Most importantly, general precautions should be strictly followed by both health-care providers and their patients, such as social distancing, wearing a mask, washing hands and using disinfectants, to reduce the risk of infection in patients with diabetes mellitus. Telehealth or remote consultations might help reduce the risk posed by direct physical contact between patients and medical personnel. These could be further ways to minimize the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission and at the same time provide continued and safe medical care to the general public.

Coronavirus infections are proven to have a huge effect on the management of diabetes mellitus because they aggravate inflammation and alter immune system responses, leading to difficulties in glycaemic control. SARS-CoV-2 infection also increases the risk of thromboembolism and is more likely to induce cardiorespiratory failure in patients with diabetes mellitus than in patients without diabetes mellitus. All of these mechanisms are now believed to contribute to the poor prognosis of patients with diabetes mellitus and COVID-19. During the COVID-19 pandemic, tight glycaemic control and management of cardiovascular risk factors are crucial for patients with diabetes mellitus. Medications used for both diabetes mellitus and CVD should be adjusted accordingly for people at high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Two experimental agents (dexamethasone and hydroxychloroquine) have shown some promise as treatment agents62,183,207. Based on these results, combined treatment with these two agents might be more beneficial than either agent alone. However, it should be kept in mind that the efficacy of dexamethasone in treating COVID-19 was proven in well-designed RCTs such as the RECOVERY study62, whereas no such compelling RCTs have been performed for hydroxychloroquine.

In conclusion, the COVID-19 global pandemic poses considerable health hazards, especially for patients with diabetes mellitus. A definitive treatment or vaccine for COVID-19 has yet to be discovered. Therefossre, preventing infection in the first place is still the best solution. Under these circumstances, patients with diabetes mellitus should make a determined effort to maintain a healthy lifestyle and to decrease potential risk factors. The optimal management strategy for such patients, such as the choice of glucose-lowering, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medications, is an important topic for current and future research.

Supplementary information

Glossary

- Cytokine storm

An uncontrolled excessive production of markers of inflammation, followed by an abnormal inflammatory response, which results from the effects of a combination of pro-inflammatory immunoactive molecules, such as interleukins, interferons, chemokines and tumour necrosis factor.

- Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

(RAAS). A hormone system that regulates blood pressure and fluid and electrolyte balance, as well as systemic vascular resistance.

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

A member of the neurotrophin family of growth factors, which are related to the canonical nerve growth factor.

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

A condition that causes abnormal blood clotting throughout the body’s small blood vessels.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Competing interests

S.L. has been a member of advisory boards or has consulted with Merck, Sharp & Dohme and NovoNordisk. S.L. has received grant support from AstraZeneca, Merck, Sharp & Dohme and Astellas. S.L. has also served on the speakers’ bureau of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly & Co., Merck, Sharp & Dohme, CKD Pharmaceutical and NovoNordisk. H.-S.K. has been a member of advisory boards or has consulted with Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Daewoong Pharmaceutical, JW Pharmaceutical and NovoNordisk. H.-S.K. has received grant support from AstraZeneca. H.-S.K. has also served on the speakers’ bureau of Eli Lilly & Co., Merck, Sharp & Dohme, YUHAN, Dong-A Pharmaceutical and NovoNordisk. M.A.N. has been a member of advisory boards or has consulted with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly & Co., Fractyl, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini/Berlin-Chemie, Merck, Sharp & Dohme and NovoNordisk. M.A.N. has received grant support from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly & Co., Menarini/Berlin-Chemie, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, Novartis Pharma and NovoNordisk. M.A.N. has also served on the speakers’ bureau of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly & Co., Menarini/Berlin-Chemie, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, NovoNordisk and Sun Pharma. J.H.B. declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Endocrinology thanks M. Rizzo and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

ClinicalTrials.gov database of COVID-19 interventional studies: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?type = Intr&cond = Covid-19

World Health Organization COVID-19 dashboard: https://covid19.who.int/

These authors contributed equally to this work: Soo Lim, Jae Hyun Bae

Contributor Information

Soo Lim, Email: limsoo@snu.ac.kr.

Michael A. Nauck, Email: michael.nauck@rub.de

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41574-020-00435-4.

References

- 1.Verity R, et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:669–677. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez-Saez J, et al. Serology-informed estimates of SARS-CoV-2 infection fatality risk in Geneva, Switzerland. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30584-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salje H, et al. Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France. Science. 2020;369:208–211. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberger DM, et al. Estimation of excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, March to May 2020. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180:1336–1344. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faust JS, Del Rio C. Assessment of deaths from COVID-19 and from seasonal influenza. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180:1045–1046. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen N, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walls AC, et al. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281–292.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:586–590. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]