Abstract

Although acute myocardial infarction is one of the most common fatal diseases worldwide, the understanding of its underlying pathogenesis continues to develop. Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) can restore myocardial oxygen and nutrient supply. However, a large number of studies have demonstrated that recovery of blood perfusion after acute ischemia causes reperfusion injury to the heart. With progress made in the understanding of the underlying mechanisms of myocardial I/R and oxidative stress, a novel area of research that merits greater study has been identified, that of I/R-induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (ERS). Cardiac I/R can alter the function of the ER, leading to the accumulation of unfolded/misfolded proteins. The resulting ERS then induces the activation of signal transduction pathways, which in turn contribute to the development of I/R injury. The mechanism of I/R injury, and the causal relationship between I/R and ERS are reviewed in the present article.

Keywords: myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, endoplasmic reticulum stress

1. Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide and occurs due to the acute occlusion of the coronary arteries (1). Although revascularization treatment has conferred proven efficacy for patients with MI, it also causes undesired ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury following the restoration of epicardial blood flow (2,3). I/R injury is defined as tissue injury that occurs when the blood supply to organs is interrupted and then returns (4). To the frustration of interventional cardiologists and other health professionals, the desire of whom is the fast restoration of blood flow to the heart muscle, successful therapeutic strategies that can prevent I/R injury in the clinic have yet to be established (5).

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an important organelle for eukaryotic cell survival and development (6,7). It is responsible for the biosynthesis, folding, assembly and modification of most secreted and transmembrane proteins. Furthermore, it serves a role in cellular lipid and steroid synthesis (8). Approximately 33% of cellular protein production and folding occurs in the ER (9). Excessive protein synthesis, beyond the capacity of the folding mechanism in cells, or excess accumulation of unfolded/misfolded proteins in the ER lumen will disrupt ER homeostasis and trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR), eventually leading to ER stress (ERS) (10). Events in the process of I/R can alter ER function and consequently influence the accumulation of unfolded/misfolded proteins. The resulting ERS then induces the activation of three signal transduction pathways, including the protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK)-eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2A (eIF2a)-activating transcription factor (ATF) 4-C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) pathway, pro-ATF6-ATF6-CHOP pathway and inositol requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1)-X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) pathway, which in turn promote the development of I/R injury (11).

The aim of the present review was to summarize current understanding of the multifactorial mechanisms that contribute to the genesis of I/R injury, and the relationship between I/R and ERS. In addition, possible future targets of therapeutic interventions to enhance recovery after I/R were discussed.

2. Mechanisms of I/R injury

Calcium (Ca2+) overload

Ca2+ overload is a complex process that serves a fundamental role in I/R damage. During ischemia, anaerobic metabolism dominates, which causes a reduction in intracellular pH. To buffer the resulting accumulation of hydrogen ions, the sodium ion exchanger discharges excessive hydrogen ions, resulting in a sodium ion influx (12). Simultaneously, ischemia also depletes ATP, which inactivates ATPases such as the Na+/K+ ATPase and reduces the efflux of Ca2+ whilst restricting the re-uptake of Ca2+ into the ER, causing Ca2+ overload (13). Opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) also occurs with the aforementioned physiological changes in the cell, leading to the dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential and further impairments to ATP production (14). Ca2+ reuptake into the ER/sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) via the SR/ER Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) is damaged by I/R, whereas Ca2+ release through the ryanodine receptor is enhanced, both of which potentiate an increase in Ca2+ levels in the cytosol (15). The ryanodine receptor is a Ca2+ channel that is located on the ER/SR network. It rapidly releases Ca2+ from the ER/SR network and exerts a wide range of physiological functions, such as functioning in myocardial cell excitation and Ca2+-dependent acceleration of ATP production, which serve an important role in maintaining the intracellular Ca2+ balance (15,16).

Ca2+ overload can damage cardiac function. Rapid accumulation of Ca2+ in cardiomyocytes after reperfusion can induce dynamic uncoupling, increase electrical conduction dispersion, and facilitate re-entry formation and arrhythmias. In addition, it can induce early or late depolarization contact, ventricular tachycardia or even ventricular fibrillation with short syndromic intervals (17,18). Ca2+ overload also promotes the damage or death of cardiomyocytes during reperfusion in multiple ways. The opening of the MPTP results in a large number of hydrogen ions entering the mitochondrial matrix from the mitochondrial intermembrane space, leading to the dissipation of the transmembrane potential gradient and obstruction of the electron transport chain. Water can also simultaneously enter the matrix down an osmotic gradient, causing mitochondrial edema, rupture or disintegration, which may lead to cell necrosis (19). Upon myocardial I/R, SERCA accelerates Ca2+ uptake and renders the cytoplasmic SR cycle in a state of high load, which leads to Ca2+ oscillation and affects the expression of Ca2+ in cells (20). Intracellular Ca2+ overload can result in excessive myocardial fiber contraction, which not only damages the cells themselves, but can also cause metabolic disorders or damage the structure of adjacent cells by mechanical forces such as traction (21). Increases in intracellular Ca2+ during myocardial ischemia can promote calpain translocation, but low intracellular pH in ischemia prevents it from being activated. During blood flow reperfusion, with the recovery of intracellular pH, calpain can be activated (22). The calpain family of cysteine proteases is activated by the elevation of Ca2+. Excessive calpain degrades a multitude of intracellular proteins in the cytoskeleton, ER and mitochondria, in turn causing damage to cells or organelles (23).

Accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

ROS are a group of unstable, active molecules, including superoxide (O2-), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radicals, which were first described as free radicals in skeletal muscle (24). ROS are generally considered to be toxic byproducts of aerobic respiration and are the major cause of macromolecular damage (25). ROS are produced by organelles and enzymes, including: i) Mitochondria, where oxygen functions as the terminal electron acceptor of the electron transport chain; ii) the ER, where H2O2 is produced as a by-product of protein folding; iii) peroxisomes, where enzymes that produce H2O2, such as polyamine oxidase, are localized; and iv) NADPH oxidase (NOX), a membrane bound enzyme complex that has a role in killing intracellular pathogens (26). Function of these organelles and enzymes will be affected following exposure to environmental cues, including chemotherapeutic drugs, ionizing radiation and environmental damage (27). O2- is a single electron reduction product of oxygen that exists in large quantities in the human body that can mediate cellular damage. O2- is produced by complexes I and III of the mitochondrial electron transfer chain, where oxygen is reduced by electron leakage. Additionally, the plasma membrane NOX (NADPH oxidases), a family of flavoenzymes, which catalyzes the oxidation of NADPH, can generate O2- (28,29). O2- is eliminated by superoxide dismutases (SODs) 1 and 2, and is then rapidly converted into H2O2 with low toxicity (30). A disruption of the homeostasis between ROS and endogenous antioxidant production results in oxidative stress (31), which leads to cellular dysfunction, DNA damage, lipid peroxidation and apoptosis induction (32). In addition, oxidative stress affects the normal function of a wide range intracellular signaling pathways and promotes the pathological development of cardiovascular diseases (33).

During cardiac ischemia, myocardial cells are in a state of hypoxia, where mitochondrial electron transfer chain complexes are significantly reduced and SOD anions are produced (34). During reperfusion, ROS levels are increased significantly due to the reduction in electron leakage and mitochondrial detoxification (34), causing oxidative stress. Free radical explosion and oxidative stress are important mechanisms of myocardial I/R injury. Mitochondrial electron transfer chain complex I is inactivated during myocardial ischemia because of the highly reductive environment with low PO2 and low ADP (35). After reperfusion, the impaired activity of complex I can also lead to ROS-induced damage to the mitochondrial phospholipids and respiratory chain super complex, potentiating the electron leakage of complex I further. This process promotes a vicious cycle of oxidative stress that ultimately leads to mitochondrial dysfunction (36). Under these conditions, excessive mitochondrial ROS cause oxidative damage to proteins, lipids and DNA, as well as excitation-contraction uncoupling, arrhythmia, cardiac hypertrophy, apoptosis, necrosis and fibrosis (37). However, low levels of ROS attenuate myocardial I/R injury through ischemic preconditioning. Recent evidence has suggested that short-term intermittent hypoxia (IH), similar to ischemic preconditioning, can serve a cardioprotective role (38). A previous study demonstrated that IH increased mitochondrial tolerance to Ca2+ overload and delayed MPTP opening induced by oxidative stress (39). In addition, a previous study has shown that IH may increase the expression of SOD and glutathione peroxidase (40).

Inflammatory cytokines and apoptotic factors

Long-term ischemia can lead to irreversible cellular necrosis, which triggers the release of a variety of pro-inflammatory mediators, including cytokines and growth factors, leading to inflammatory cell infiltration (41). During late stage I/R, genes associated with inflammation are activated to produce mediators, including IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α IFN-regulating factor and NF-κB, all of which promote neutrophil adhesion and transmembrane migration, leukocyte infiltration, and cytokine and chemokine release, eventually leading to cell death. I/R can activate the inflammation cascade to cause further tissue damage (42). TNF-α participates in the development of myocardial injury during I/R injury, during which its expression level is increased, promoting adhesion and interaction between leukocytes and endothelial cells (43). This increases the infiltration of granulocytes into the I/R region to mediate myocardial cell damage (43). IL-1 is secreted by activated monocytes and macrophages, and its expression is also significantly increased during I/R. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) participates in the adhesion of leukocytes to vascular endothelial cells and induces cytotoxicity by adhering to cardiomyocytes (44). Enhanced ICAM-1 binding can feed back to endothelial cells and macrophages to promote the expression of inflammatory mediators or cytokines (44). During I/R, the release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines leads to the activation of neutrophils and macrophages, which promotes tissue damage (45). Neutrophil infiltration serves an important role in myocardial I/R injury. This step is initiated by the binding of vascular endothelial adhesion molecules with corresponding ligands on neutrophils to mediate the adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial cells. Mast cells serve an important role in stimulating the inflammatory response by releasing regulators that can trigger the cascade of cytokine release (46). Cyclic inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein, IL-6 and IL-1, are associated with increased infarct size and poor prognosis. In recent years, pro-inflammatory cells such as monocytes and macrophages have been documented to be a potential cause of MI using a number of cell tracking and molecular imaging techniques (47).

During I/R, different gene families can also serve distinct roles in apoptosis. Apoptosis is a tightly controlled process that is conserved among species and involves the Bcl-2 and caspase families of proteins in addition to oncogenes, such as c-Myc and p53(48). The activation, upregulation, translocation and integration of precursor Bcl-2 proteins, including Bax, BH3 interacting-domain death agonist, p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) and Bcl-2 interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), into the mitochondrial membrane within ischemic injury tissues has been previously reported (49,50). In addition, pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins have been found to regulate Ca2+ homeostasis, which is an important mechanism of I/R injury (51). The caspase family also serves a key role in I/R-induced cell death. Pan-cysteine aspartase inhibitors, including zVAD-FMK and MX1013, can attenuate apoptosis and cell death induced by I/R (52,53). However, it has been previously reported that caspase inhibition may instead drive the cell towards necrotic death (54). A number of studies have demonstrated that the overexpression of BNIP3 in HL-1 myocardial cells can activate Bax to promote the opening of the MPTP and increase cell death in response to I/R injury (55,56).

Changes in microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs)

miRNAs are short, single-stranded non-coding RNAs that are 21-23 nucleotides in length and regulate gene expression by inhibiting translation or promoting the degradation of RNA (57). Mature miRNAs are processed from primary miRNA, which is cleaved by a microprocessor complex that consists of the RNase-III endonuclease Drosha, RNA-binding protein DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 and other cofactors, to produce 70-100 nucleotide hairpin precursor small RNAs. Following export to the cytoplasm by the nuclear export protein exportin-5, they are trimmed by the RNase III ribonuclease dicer to produce a mature miRNA duplex that is ~21 nucleotides in length (58).

Several studies have demonstrated that miRNA function is closely associated with cardiovascular disease, and a number of non-cardiac miRNAs are reported to be biomarkers of myocardial injury and predictors of clinical outcomes after acute MI. miR-633b and miR-1291 have been documented to indicate MI with high specificity and sensitivity (59), whereas miR-150 and miR-486 expression levels could be used to distinguish between patients with and without ST-elevation MI (60). A previous study revealed that heart biopsies from patients with heart failure demonstrated a significant increase in miR-377 expression compared with that in normal control hearts (61). In a mouse cardiac I/R model, human CD34+ cells in immune-deficient mice were silenced following the intra-myocardial transplantation of miR-377, which promoted neovascularization and reduced interstitial fibrosis 28 days after I/R induction to improve left ventricular function (61).

MiRNAs serve significant roles in cardiac I/R injury and function by a wide range of different mechanisms. A previous study demonstrated that miR-1 and miR-133 mediated opposite effects when regulating myocyte survival in I/R models, where miR-1 was pro-apoptotic and miR-133 was anti-apoptotic (62). This difference may be due to their respective downstream targets. Increased miR-1 expression resulted in the downregulation of several anti-apoptotic genes, including heat shock protein (hsp)60, hsp70, insulin-like growth factor-1 and Bcl-2, whereas miR-133 negatively regulated the expression of pro-apoptotic genes, such as caspase-9 and caspase-3 (62-64). Another study revealed that miR-133 overexpression reduced cardiac fibrosis after transverse aortic banding compared with that in normal controls, implicating the cardioprotective effects of miR-133a on I/R-triggered cardiac remodeling (65). miR-21 has been demonstrated to protect cardiomyocytes from I/R injury by targeting several apoptotic genes, including phosphatase and tensin homolog, cell death 4 and Fas ligand (66-68). Furthermore, miR-21 has been reported to inhibit the proliferation, migration and tubulogenesis of endothelial cells, and promote the survival of cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts after myocardial I/R (69). miR-25 and miR-145 can reduce mitochondrial ROS stress and Ca2+ overload by inhibiting the expression of mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) (70). miR-214 may protect cardiomyocytes from oxidative damage induced by ROS formation initiated by Ca2+ overload by inhibiting sodium/Ca2+ exchanger 1 (71-73).

From the aforementioned studies, it can be concluded that miRNAs regulate the expression of pro-apoptotic/anti-apoptotic genes to regulate cardiac fibrosis, inflammation, ROS generation and Ca2+ homeostasis. A number of studies have demonstrated that various miRNAs, including miR-21(67), miR-144/451(74), miR-192(75) and miR-199a (76), are associated with ischemic preconditioning. Additionally, some experimental studies have revealed that inhibition of miR-15 and miR-92a in pig models of acute myocardial I/R, especially at the beginning of reperfusion, can reduce the size of the MI (77,78). This suggests that miRNA treatment may be a feasible therapeutic approach (75).

3. Pathways of ERS

ERS is an evolutionarily conserved cell stress response that is associated with numerous diseases, including cardiovascular, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, and diabetes, renal failure, osteosarcoma and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (79-85). Under physiological conditions, the ER is an important organelle that serves a key role in cellular processes, including protein folding, assembly, modification and secretion, lipid synthesis and Ca2+ storage. However, when the ER is exposed to stress stimuli, such as ROS exposure and Ca2+ overload, homeostasis is impaired, which results in the accumulation of unfolded/misfolded proteins (86). These changes may eventually lead to ER dysfunction, collectively known as ERS (86).

Several ER transmembrane sensors are expressed to detect the accumulation of unfolded proteins, including PERK, ATF6 and IRE1, which activate the signal pathways of (eIF2α-ATF4-DNA-damage-inducible transcript/CHOP, pro-ATF6-cleaved ATF6-CHOP, and IRE1-spliced (Xbp1), respectively (79). This upregulates the expression of ER chaperones and ER-related degradation components (6). The UPR can activate the ER chaperone glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) following isolation by any of the three ER sensors (PERK, ATF6 and IRE1). In the absence of ERS, binding to GRP78 results in the inactivation of these sensors. GRP78 is released from the sensors, where they can interact with misfolded and unfolded proteins when ERS occurs. Ultimately, the UPR is triggered by the transcription of genes encoding proteins involved in this process, leading to a reduction in global protein synthesis (87). The ultimate purpose of the UPR is to restore normal ER function, the failure of which results in apoptosis (88,89). The three main ERS pathways are described in the following sections.

PERK-eIF2a-ATF4-CHOP pathway

A previous study indicated that the PERK signaling pathway serves an essential role in preventing the abnormal accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER to promote cell survival (90). PERK is a type I transmembrane ER protein that has a ligand-independent dimerization domain at the N-terminus, which is concealed by binding immunoglobulin protein (BIP)/GRP78 in the absence of ERS, and a serine/threonine protein kinase domain at the C-terminus without endonuclease activity (91). PERK can block the translation of most proteins, leaving only a specific few, such as ATF4 and CHOP, to be translated (92,93). Translation of ATF4 activates the expression of CHOP by directly interacting with its 5'-untranslated region (92).

Activation of PERK leads to eIF2α phosphorylation. In addition, it promotes caspase-12 and CHOP overexpression, which can direct ERS towards cell apoptosis (94). CHOP can in turn activate downstream targets during ERS, resulting in apoptotic cell death (95).

Pro-ATF6-ATF6-CHOP pathway

One arm of the UPR is the activation of the ER membrane protein ATF6, a fragment of which is translocated into the nucleus to activate the transcription of genes that mediate protein folding (96). ATF6 has two subtypes: ATF6α and ATF6β (96). The accumulation of misfolded proteins causes ATF6α to be transported to the Golgi apparatus (97,98). There, it is sheared and the N-terminal fragment, p50-ATF6a, is transferred to the nucleus, where it regulates the transcription of genes associated with protein quality control, translocation, folding and degradation (99). ERS leads to the vesicular exit of ER ATF6, which is subsequently degraded by site-1 and site-2 proteases (S1P and S2P) in the Golgi complex. This cleavage cuts off the cytoplasmic domain of ATF6 from its transmembrane anchorage and intraluminal domain, following which the cytoplasmic ATF6 domain enters the nucleus to transcriptionally upregulate UPR target genes (100).

IRE1-XBRLP1 pathway

IRE1 is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein that can be divided into two categories: IRE1α and IRE1β. IRE1α is widely expressed in different tissues, whereas IRE1β is only expressed in intestinal epithelial cells (101). IRE1α senses the accumulation of unfolded proteins and is activated by dissociation with the ER chaperone GRP78/BIP (102-104). IRE1 then dimerizes and trans-autophosphorylates itself to activate its endonuclease domain under ERS. This endonuclease domain then acts on the Xbp1 gene and performs an unconventional splicing. After 26 nucleotides are removed, a spliced mRNA is produced, which increases the transcription of UPR target genes (105). Activation of the ER splicing factor IRE1α and the splicing transcription factor Xbp1 can induce the transcription of chaperones, which are necessary for facilitating protein folding (105). A previous study reported that the activation of the PERK-eIF2α and IRE1α-Xbp1 signaling pathways inhibited apoptosis and promoted proliferation without affecting ERK and AKT signaling activation (93). The UPR has been associated with a number of diseases, including cardiovascular, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, and IRE1 has been the focus of several drug discovery projects such as ligands that interact with IREα's kinase and pre-emptive activation of IRE1α's homeostatic mode (79,80,106).

4. I/R as an activator of the UPR

The UPR is associated with numerous pathological processes, including cardiovascular disease, I/R injury, neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes mellitus, viral infection and cancer (107). Some of the earliest studies on the effects of I/R on the UPR were conducted in the brain (81,108). A previous study has demonstrated that several pathways of the UPR are activated in the ischemic rabbit brain such as that of PERK-Xbp1-eIF2α, leading to translation arrest (108). Several studies have demonstrated that Xpb1, genetic markers of GRP78 and the UPR are activated in hypoxic cultured ventricular myocytes or HL-1 atrial myocytes from neonatal rats or adult mice (109-111). Therefore, ischemia and I/R can activate numerous components of the UPR in cardiomyocytes both in vivo and in vitro (112). In a neuronal studie ERS has been reported to be associated with neuronal cell death following ischemia (113). A study demonstrated that global cerebral I/R induced time-dependent differences in ER gene expression at both mRNA and protein levels, which was affected by pre-ischemic therapy (114).

Cardiomyocyte injury is induced by four pathophysiological events during I/R: Ca2+ overload, ROS accumulation, inflammatory cytokine release and apoptotic factor release. In addition, changes in the miRNA expression profile is another method by which I/R can regulate the UPR, as described in an earlier part of this review. As described in the present review, oxidative stress serves an important role in the I/R process, as ROS can activate apoptosis and ERS at various stages. The FOXO family of transcription factors is involved in a number of biological processes, including the oxidative stress response, cell proliferation, apoptosis and metabolism (115). The most well-studied members of the FOXO family include FOXO1, FOXO3, FOXO4 and FOXO6(115). A Previous study has demonstrated that FOXO4 serves an important role in ROS-induced apoptosis (116). Increased ROS production leads to acute renal ischemia by negatively interfering with the normal function of signaling pathways, inducing inflammatory infiltration and renal cell death (117). A study previously revealed that treatment with the bromodomain-containing protein 4 inhibitor, which exerts protective effects against renal I/R injury, suppressed I/R-induced apoptosis and ERS by activating PI3K/AKT signaling and blocking FOXO4-dependent ROS production (118). Blocking ROS using N-acetylcysteine has also been demonstrated to inhibit hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis and ERS protein expression. The relationship between ROS and ERS-induced apoptosis has been confirmed, where ROS production can induce apoptotic cell death and ERS (118).

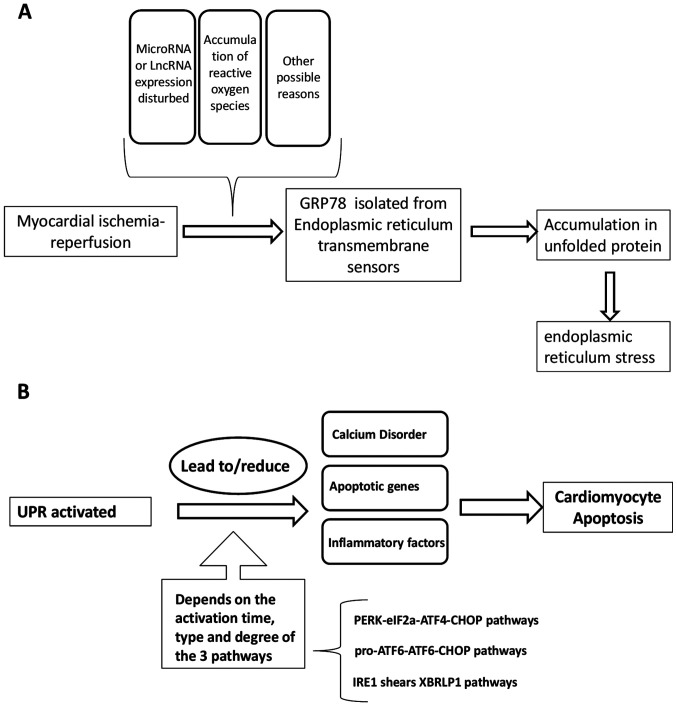

One previous study demonstrated that H2S pretreatment and overexpression of miR-133a in the myocardium inhibited cardiomyocyte apoptosis and enhanced cell viability (119). In addition, concomitant miR-133a overexpression has been revealed to significantly increase cardiomyocyte proliferation, migration and invasion, in turn reversing I/R-induced ERS and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. This suggests that miR-133a protects cardiomyocytes against I/R-induced ERS and subsequent apoptosis (119). A long non-coding RNA named urothelial carcinoma-associated 1 (UCA1), is only expressed in the heart (120). It has previously been reported that cardiac I/R triggers the expression of UCA1, and the production of ROS in cells and mitochondria to mediate apoptosis by oxidative stress and ERS. Overexpression of UCA1 can also protect H9C2 cells from ERS and cell apoptosis induced by I/R (121). After co-treatment with TUDCA, a drug for clinical use that can protect cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress-induced injury (122), H9C2 cell injury induced by the effect of UCA1 siRNA was reversed (121). To summarize the activation function of I/R to UPR, as described hereafter, a general scheme is presented in Fig. 1A.

Figure 1.

(A) I/R as an activator of the UPR. (B) UPR, in turn, affects I/R damage. I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; UPR, unfolded protein response; GRP78, glucose regulated protein 78; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; PERK, protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; eIF2a, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2a; IRE, inositol responsive element; CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein; XBP1, X-box binding protein 1.

5. UPR in turn mediates I/R damage

The ER serves a pivotal role in cardiomyocytes, as the correct synthesis and folding of proteins in the ER is indispensable for the normal functioning of the heart (123). However, although ERS and the UPR have been extensively studied in non-muscle ER, there remains an insufficient number of studies on ERS and the UPR in the cardiovascular field (124).

If the UPR signal activation during the early stages of ERS is not sufficient in resolving stress, the persistent activation of proximal effectors (PRRK, ATF6 and IRE1) will result in the appearance of a distinct UPR-induced protein setup, where other signaling pathways are activated, all of which combine to promote cell death (125,126). Notably, a previous study indicated that pre-activation of ATF6 in the hearts of transgenic mice conferred protective effects against I/R injury (127). In addition, a study indicated that the upregulation of GRP78 during ischemic preconditioning protected cultured cardiomyocytes from further ischemic damage (128). These studies suggested that when the UPR is activated in the heart during ischemia or I/R, it may exert protective effects against the stress response in myocardial cells. By contrast, several studies have demonstrated that UPR may lead to I/R injury of the heart. A previous study demonstrated that overexpression of the ERS response protein PUMA potentiated apoptosis in cultured cardiomyocytes via the UPR (129). Another study revealed that UPR activation promoted the activation of caspase-3, JNK and p53, which contributed to cardiomyocyte apoptosis (130). Additionally, in cultured cardiac myocytes, UPR mediated protective effects against ischemia activation in the early stages of ischemia, whereas the same response resulted in predominantly apoptotic characteristics in the latter stages (131). The distinct functions of the UPR may be dependent on the degree of ATF6, PERK and IRE-1 activation, and the nature of the ERS. ATF6 may mediate the activation of mostly protective proteins, whilst PERK may induce the activation of apoptotic genes (127). Therefore, brief ischemic stress may lead to changes in the proteome under the regulation of the UPR to promote protective effects, whereas prolonged ischemia may lead to changes in the proteome leading to cellular damage.

It has previously been reported that pathological ERS is relevant in a variety of physiological outcomes, including impaired Ca2+ homeostasis, increased apoptotic signaling, disrupted protein secretion and increased apoptotic signaling (132-134).

During ERS, CHOP has been demonstrated to induce the expression of ER oxidase 1, which activates inositol triphosphate receptor-mediated Ca2+ release into the cytosol and activates CaMKII to induce apoptosis (135-137). It has been revealed that Xbp1 and ATF6 may mediate the overexpression of GRP94, which could attenuate myocardial cell necrosis induced by Ca2+ overload or ischemia (138).

Ca2+ overload serves an important role in ERS-induced I/R injury. The Ca2+ dependence of cell death can be enhanced by a reduction in ATP. ATP concentration is decreased during ERS, which reduces the levels of intracellular Ca2+ stored in the ER (129). It has previously been reported that inhibiting calpain can improve ischemic myocardial injury and myocardial function in an experimental model of myocardial I/R (139-141).

The UPR can regulate a number of mitochondrial functions, including bioenergetics, membrane potential and the degree of cytochrome c release (142). The UPR can also serve a role in immune function. A previous study revealed that cathepsin-induced ERS enhanced the recruitment of IFN regulatory factor-3 and cAMP response element binding protein (CREB/CBP)/p300 to the murine IFNB1 promoter during lipopolysaccharide stimulation. ERS-related inflammation occurred through Xbp1 binding to a potential enhancer element 6 kb distal to the IFNB1 gene, which may enhance the recruitment of CBP/p300 and IFN regulatory transcription factor to the IFNB1 enhanceosome (143). This observation indicated a novel role of UPR-dependent transcription in the regulation of inflammatory cytokines, which may be of significance to the pathogenesis of diseases involving ERS and type I IFN. One potential avenue of study may be the relationship among viral infection, I/R injury and inflammatory diseases (143). ERS can activate nucleotide binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 1 (NLRP1) inflammatory bodies by activating the NF-κB signaling pathway, which may then promote myocardial I/R injury (144). NLRPs are classified as typical inflammasomes that include NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammatory bodies. They can activate caspase-1, resulting in the maturation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18(145). How the UPR in turn mediates I/R damage is summarized in Fig. 1B.

There are several important proteins that are activated by ERS, including ATF6, Xbp1, ATF4, CHOP and IRE1. ATF6 normally functions in the adaptive UPR to accelerate the remodeling of cellular physiology and recovery following acute physiological and pathological injury (146). ATF6 can dimerize with UPR-regulated basic leucine zipper transcription factors, such as Xbp1, by S1P/S2P-dependent proteolysis, or associate with other stress-responsive signaling pathways such as mTOR signaling (147,148). In addition, ATF6 has been reported to induce the expression of the Ca2 + pump SERCA2a and the expression of several antioxidant genes (149,150).

Xbp1 has been revealed to exert protective effects against I/R injury in the heart and the brain (133,151-153), as overexpression of Xbp1 can inhibit cell death induced by oxygen glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R These findings suggested that inhibiting Xbp1 activation may accelerate neuronal cell death after I/R, which can be exploited as a therapeutic strategy for brain I/R injury (154). Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that ERS serves a key role in I/R-induced cell dysfunction (155), where destruction of the ER pathway can result in neuronal cell death. ERS is associated with the pathology of brain I/R injury. OGD/R stress temporarily inactivates Xbp1 splicing, resulting in accelerated neuronal death due to ER dysfunction. Subsequent Xbp1 reactivation may be neuroprotective against OGD/R stress (154).

ATF4 induces the expression of CHOP under mild ERS. However, under chronic ERS, PERK then significantly increases CHOP expression, in turn suppressing the expression of Bcl-2 to increase cell death (156). In addition, PERK phosphorylates Kelch-like Ech-related protein 1, which releases Nrf2 from inhibition and translocates into the nucleus to activate the expression of antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes (157). CHOP has also been reported to upregulate the expression of PUMA and the pro-apoptotic protein Bim, thereby inducing mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis (158,159). IRE1 is associated with autophagy activation, which is an important pro-survival defense mechanism against cardiac pathology, including hypertrophy and I/R (160).

6. Conclusion and future perspectives

In the present article, numerous possible causes of myocardial I/R injury, including Ca2+ overload, ROS accumulation, increase in expression of inflammatory cytokines and apoptotic factors, miRNA change and ERS were described. These factors not only lead to secondary cardiac injury but can also hinder the reconstruction of blood vessels after clinical treatment (161). Cardiac I/R injury induces changes of ERS in a process that is mainly mediated by three pathways involved in the accumulation of unfolded proteins, which causes cell damage. At the beginning of the response, a cellular protective response ensues, which then becomes apoptotic in the latter stages. However, to understand the specific mechanism underlying these processes, further study is required. Appropriate intervention in the ERS process may serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for heart I/R injury, including intervention in the expression of ligands and their receptors in the ERS pathways. With further study of cardiac ERS and I/R injury, strengthening the understanding of the mechanism underlying I/R injury will facilitate the optimization of treatment regimens. If the occurrence and development of myocardial cell apoptosis can be prevented, it may become possible to alleviate I/R injury, which will facilitate the development of treatment strategies and drug discovery for myocardial I/R.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The current study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81770292), Key Workstation Projects of He Lin (grant no. 18331101) and Wenzhou Science and Technology Major Projects (grant no. 2018ZY007).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YR and LL conceived and designed the review. YR, JZ and QJ collected the related literature. MC, KJ and ZW analyzed the related papers. YR wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Baulina N, Osmak G, Kiselev I, Matveeva N, Kukava N, Shakhnovich R, Kulakova O, Favorova O. NGS-identified circulating miR-375 as a potential regulating component of myocardial infarction associated network. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;121:173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.07.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nunez-Gomez E, Pericacho M, Ollauri-Ibanez C, Bernabeu C, Lopez-Novoa JM. The role of endoglin in post-ischemic revascularization. Angiogenesis. 2017;20:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10456-016-9535-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou H, Ma Q, Zhu P, Ren J, Reiter RJ, Chen Y. Protective role of melatonin in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury: From pathogenesis to targeted therapy. J Pineal Res. 2018;64(e12471) doi: 10.1111/jpi.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jennings RB, Sommers HM, Smyth GA, Flack HA, Linn H. Myocardial necrosis induced by temporary occlusion of a coronary artery in the dog. Arch Pathol. 1960;70:68–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson SM, Ferdinandy P, Andreadou I, Bøtker HE, Heusch G, Ibáñez B, Ovize M, Schulz R, Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ, et al. Multitarget strategies to reduce myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu C, Bailly-Maitre B, Reed JC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Cell life and death decisions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2656–2664. doi: 10.1172/JCI26373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao S, Liu Y, Wang F, Xu D, Xie P. N-acetylcysteine protects against microcystin-LR-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and germ cell apoptosis in zebrafish testes. Chemosphere. 2018;204:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Jin X, Su R, Li Z. The reproductive toxicology of male SD rats after PM2.5 exposure mediated by the stimulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Chemosphere. 2017;189:547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almanza A, Carlesso A, Chintha C, Creedican S, Doultsinos D, Leuzzi B, Luís A, McCarthy N, Montibeller L, More S, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling-from basic mechanisms to clinical applications. FEBS J. 2019;286:241–278. doi: 10.1111/febs.14608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzel E, Arlier S, Guzeloglu-Kayisli O, Tabak MS, Ekiz T, Semerci N, Larsen K, Schatz F, Lockwood CJ, Kayisli UA. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and homeostasis in reproductive physiology and pathology. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(792) doi: 10.3390/ijms18040792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xin W, Li X, Lu X, Niu K, Cai J. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated apoptosis in a heart failure model induced by chronic myocardial ischemia. Int J Mol Med. 2011;27:503–509. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanada S, Komuro I, Kitakaze M. Pathophysiology of myocardial reperfusion injury: Preconditioning, postconditioning, and translational aspects of protective measures. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1723–H1741. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00553.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marban E, Kitakaze M, Kusuoka H, Porterfield JK, Yue DT, Chacko VP. Intracellular free calcium concentration measured with 19F NMR spectroscopy in intact ferret hearts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6005–6009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.6005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalogeris T, Baines CP, Krenz M, Korthuis RJ. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2012;298:229–317. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394309-5.00006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szydlowska K, Tymianski M. Calcium, ischemia and excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakob R, Beutner G, Sharma VK, Duan Y, Gross RA, Hurst S, Jhun BS, O-Uchi J, Sheu SS. Molecular and functional identification of a mitochondrial ryanodine receptor in neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2014;575:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peracchia C. Chemical gating of gap junction channels; roles of calcium, pH and calmodulin. Biochim Biophysica Acta. 2004;1662:61–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tribulova N, Knezl V, Szeiffova Bacova B, Egan Benova T, Viczenczova C, Gonçalvesova E, Slezak J. Disordered myocardial Ca(2+) homeostasis results in substructural alterations that may promote occurrence of malignant arrhythmias. Physiol Res. 2016;65 (Suppl 1):S139–S148. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.933388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javadov S, Hunter JC, Barreto-Torres G, Parodi-Rullan R. Targeting the mitochondrial permeability transition: Cardiac ischemia-reperfusion versus carcinogenesis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;27:179–190. doi: 10.1159/000327943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdallah Y, Gkatzoflia A, Gligorievski D, Kasseckert S, Euler G, Schlüter KD, Schäfer M, Piper HM, Schäfer C. Insulin protects cardiomyocytes against reoxygenation-induced hypercontracture by a survival pathway targeting SR Ca2+ storage. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu H, Yang H, Rhee JW, Zhang JZ, Lam CK, Sallam K, Chang ACY, Ma N, Lee J, Zhang H, et al. Modelling diastolic dysfunction in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3685–3695. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inserte J, Hernando V, Garcia-Dorado D. Contribution of calpains to myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;96:23–31. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croall DE, Ersfeld K. The calpains: Modular designs and functional diversity. Genome Biol. 2007;8(218) doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Commoner B, Townsend J, Pake GE. Free radicals in biological materials. Nature. 1954;174:689–691. doi: 10.1038/174689a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cadenas S. Mitochondrial uncoupling, ROS generation and cardioprotection. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2018;1859:940–950. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meitzler JL, Antony S, Wu Y, Juhasz A, Liu H, Jiang G, Lu J, Roy K, Doroshow JH. NADPH oxidases: A perspective on reactive oxygen species production in tumor biology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:2873–2889. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziech D, Franco R, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced genetic and epigenetic alterations in human carcinogenesis. Mutation Res. 2011;711:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brand MD. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambeth JD. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:181–189. doi: 10.1038/nri1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang P, Feng L, Oldham EA, Keating MJ, Plunkett W. Superoxide dismutase as a target for the selective killing of cancer cells. Nature. 2000;407:390–395. doi: 10.1038/35030140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srinivas US, Tan BWQ Vellayappan BA, Jeyasekharan AD. ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox Biol. 2019;25(101084) doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.101084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azevedo PS, Polegato BF, Minicucci MF, Paiva SA, Zornoff LA. Cardiac remodeling: Concepts, clinical impact, pathophysiological mechanisms and pharmacologic treatment. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;106:62–69. doi: 10.5935/abc.20160005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moris D, Spartalis M, Spartalis E, Karachaliou GS, Karaolanis GI, Tsourouflis G, Tsilimigras DI, Tzatzaki E, Theocharis S. The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases and the clinical significance of myocardial redox. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(326) doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.06.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartz RR, Suliman HB, Piantadosi CA. Redox mechanisms of cardiomyocyte mitochondrial protection. Front Physiol. 2015;6(291) doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee HL, Chen CL, Yeh ST, Zweier JL, Chen YR. Biphasic modulation of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1410–H1422. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00731.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen YR, Zweier JL. Cardiac mitochondria and reactive oxygen species generation. Circ Res. 2014;114:524–537. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Angelova PR, Abramov AY. Functional role of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in physiology. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;100:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang JC, Lien CF, Lee WS, Chang HR, Hsu YC, Luo YP, Jeng JR, Hsieh JC, Yang KT. Intermittent hypoxia prevents myocardial mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and cell death during ischemia/reperfusion: The role of reactive oxygen species. Cells. 2019;8(564) doi: 10.3390/cells8060564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu WZ, Xie Y, Chen L, Yang HT, Zhou ZN. Intermittent high altitude hypoxia inhibits opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores against reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguilar M, Gonzalez-Candia A, Rodríguez J, Carrasco-Pozo C, Cañas D, García-Herrera C, Herrera EA, Castillo RL. Mechanisms of cardiovascular protection associated with intermittent hypobaric hypoxia exposure in a rat model: Role of Oxidative Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(366) doi: 10.3390/ijms19020366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jordan JE, Zhao ZQ, Vinten-Johansen J. The role of neutrophils in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:860–878. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandrasekar B, Colston JT, Geimer J, Cortez D, Freeman GL. Induction of nuclear factor kappaB but not kappaB-responsive cytokine expression during myocardial reperfusion injury after neutropenia. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1579–1588. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugano M, Hata T, Tsuchida K, Suematsu N, Oyama J, Satoh S, Makino N. Local delivery of soluble TNF-alpha receptor 1 gene reduces infarct size following ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;266:127–132. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000049149.03964.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Merchant SH, Gurule DM, Larson RS. Amelioration of ischemia-reperfusion injury with cyclic peptide blockade of ICAM-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1260–H1268. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00840.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dar WA, Sullivan E, Bynon JS, Eltzschig H, Ju C. Ischaemia reperfusion injury in liver transplantation: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Liver Int. 2019;39:788–801. doi: 10.1111/liv.14091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhattacharya K, Farwell K, Huang M, Kempuraj D, Donelan J, Papaliodis D, Vasiadi M, Theoharides TC. Mast cell deficient W/Wv mice have lower serum IL-6 and less cardiac tissue necrosis than their normal littermates following myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2007;20:69–74. doi: 10.1177/039463200702000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yap ML, Peter K. Molecular positron emission tomography in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion. Circ Res. 2019;124:827–829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.314754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valente M, Calabrese F. Liver and apoptosis. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31:73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Metukuri MR, Beer-Stolz D, Namas RA, Dhupar R, Torres A, Loughran PA, Jefferson BS, Tsung A, Billiar TR, Vodovotz Y, Zamora R. Expression and subcellular localization of BNIP3 in hypoxic hepatocytes and liver stress. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G499–G509. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90526.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu B, Qiu W, Wang P, Yu H, Cheng T, Zambetti GP, Zhang L, Yu J. p53 independent induction of PUMA mediates intestinal apoptosis in response to ischaemia-reperfusion. Gut. 2007;56:645–654. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scorrano L, Oakes SA, Opferman JT, Cheng EH, Sorcinelli MD, Pozzan T, Korsmeyer SJ. BAX and BAK regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+: A control point for apoptosis. Science. 2003;300:135–139. doi: 10.1126/science.1081208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kobayashi A, Imamura H, Isobe M, Matsuyama Y, Soeda J, Matsunaga K, Kawasaki S. Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in ischemia-reperfusion injury of rat liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G577–G585. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.2.G577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang W, Guastella J, Huang JC, Wang Y, Zhang L, Xue D, Tran M, Woodward R, Kasibhatla S, Tseng B, et al. MX1013, a dipeptide caspase inhibitor with potent in vivo antiapoptotic activity. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:402–412. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Van Herreweghe F, Vanden Berghe T. The role of the kinases RIP1 and RIP3 in TNF-induced necrosis. Sci Signal. 2010;3(re4) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3115re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kubli DA, Ycaza JE, Gustafsson AB. Bnip3 mediates mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death through Bax and Bak. Biochem J. 2007;405:407–415. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kubli DA, Quinsay MN, Huang C, Lee Y, Gustafsson AB. Bnip3 functions as a mitochondrial sensor of oxidative stress during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2025–H2031. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00552.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poller W, Dimmeler S, Heymans S, Zeller T, Haas J, Karakas M, Leistner DM, Jakob P, Nakagawa S, Blankenberg S, et al. Non-coding RNAs in cardiovascular diseases: Diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2704–2716. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winter J, Jung S, Keller S, Gregory RI, Diederichs S. Many roads to maturity: microRNA biogenesis pathways and their regulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:228–234. doi: 10.1038/ncb0309-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng L, Chun-Guang Q, Bei-Fang L, Xue-Zhi D, Zi-Hao W, Yun-Fu L, Yan-Ping D, Yang-Gui L, Wei-Guo L, Tian-Yong H, Zhen-Wen H. Clinical impact of circulating miR-133, miR-1291 and miR-663b in plasma of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9(89) doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang R, Lan C, Pei H, Duan G, Huang L, Li L. Expression of circulating miR-486 and miR-150 in patients with acute myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15(51) doi: 10.1186/s12872-015-0042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Joladarashi D, Garikipati VNS, Thandavarayan RA, Verma SK, Mackie AR, Khan M, Gumpert AM, Bhimaraj A, Youker KA, Uribe C, et al. Enhanced cardiac regenerative ability of stem cells after ischemia-reperfusion injury: Role of human CD34+ cells deficient in MicroRNA-377. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2214–2226. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu C, Lu Y, Pan Z, Chu W, Luo X, Lin H, Xiao J, Shan H, Wang Z, Yang B. The muscle-specific microRNAs miR-1 and miR-133 produce opposing effects on apoptosis by targeting HSP60, HSP70 and caspase-9 in cardiomyocytes. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3045–3052. doi: 10.1242/jcs.010728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang Y, Zheng J, Sun Y, Wu Z, Liu Z, Huang G. MicroRNA-1 regulates cardiomyocyte apoptosis by targeting Bcl-2. Int Heart J. 2009;50:377–387. doi: 10.1536/ihj.50.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu XY, Song YH, Geng YJ, Lin QX, Shan ZX, Lin SG, Li Y. Glucose induces apoptosis of cardiomyocytes via microRNA-1 and IGF-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:548–552. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matkovich SJ, Wang W, Tu Y, Eschenbacher WH, Dorn LE, Condorelli G, Diwan A, Nerbonne JM, Dorn GW II. MicroRNA-133a protects against myocardial fibrosis and modulates electrical repolarization without affecting hypertrophy in pressure-overloaded adult hearts. Circ Res. 2010;106:166–175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.202176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng Y, Liu X, Zhang S, Lin Y, Yang J, Zhang C. MicroRNA-21 protects against the H(2)O(2)-induced injury on cardiac myocytes via its target gene PDCD4. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheng Y, Zhu P, Yang J, Liu X, Dong S, Wang X, Chun B, Zhuang J, Zhang C. Ischaemic preconditioning-regulated miR-21 protects heart against ischaemia/reperfusion injury via anti-apoptosis through its target PDCD4. Cardiovas Res. 2010;87:431–439. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sayed D, He M, Hong C, Gao S, Rane S, Yang Z, Abdellatif M. MicroRNA-21 is a downstream effector of AKT that mediates its antiapoptotic effects via suppression of Fas ligand. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20281–20290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.109207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu H, Fan GC. Role of microRNAs in the reperfused myocardium towards post-infarct remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:284–292. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Magenta A, Dellambra E, Ciarapica R, Capogrossi MC. Oxidative stress, microRNAs and cytosolic calcium homeostasis. Cell Calcium. 2016;60:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cha MJ, Jang JK, Ham O, Song BW, Lee SY, Lee CY, Park JH, Lee J, Seo HH, Choi E, et al. MicroRNA-145 suppresses ROS-induced Ca2+ overload of cardiomyocytes by targeting CaMKIIδ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;435:720–726. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pan L, Huang BJ, Ma XE, Wang SY, Feng J, Lv F, Liu Y, Liu Y, Li CM, Liang DD, et al. MiR-25 protects cardiomyocytes against oxidative damage by targeting the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:5420–5433. doi: 10.3390/ijms16035420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aurora AB, Mahmoud AI, Luo X, Johnson BA, van Rooij E, Matsuzaki S, Humphries KM, Hill JA, Bassel-Duby R, Sadek HA, Olson EN. MicroRNA-214 protects the mouse heart from ischemic injury by controlling Ca2+ overload and cell death. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1222–1232. doi: 10.1172/JCI59327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang X, Zhu H, Zhang X, Liu Y, Chen J, Medvedovic M, Li H, Weiss MJ, Ren X, Fan GC. Loss of the miR-144/451 cluster impairs ischaemic preconditioning-mediated cardioprotection by targeting Rac-1. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:379–390. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ong SB, Katwadi K, Kwek XY, Ismail NI, Chinda K, Ong SG, Hausenloy DJ. Non-coding RNAs as therapeutic targets for preventing myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2018;22:247–261. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2018.1439015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ong SG, Hausenloy DJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor as a therapeutic target for cardioprotection. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;136:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hinkel R, Penzkofer D, Zühlke S, Fischer A, Husada W, Xu QF, Baloch E, van Rooij E, Zeiher AM, Kupatt C, Dimmeler S. Inhibition of microRNA-92a protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in a large-animal model. Circulation. 2013;128:1066–1075. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hullinger TG, Montgomery RL, Seto AG, Dickinson BA, Semus HM, Lynch JM, Dalby CM, Robinson K, Stack C, Latimer PA, et al. Inhibition of miR-15 protects against cardiac ischemic injury. Circ Res. 2012;110:71–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.244442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Minamino T, Kitakaze M. ER stress in cardiovascular disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:1105–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lindholm D, Wootz H, Korhonen L. ER stress and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:385–392. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matus S, Glimcher LH, Hetz C. Protein folding stress in neurodegenerative diseases: A glimpse into the ER. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:239–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell. 2010;140:900–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chiang CK, Hsu SP, Wu CT, Huang JW, Cheng HT, Chang YW, Hung KY, Wu KD, Liu SH. Endoplasmic reticulum stress implicated in the development of renal fibrosis. Mol Med. 2011;17:1295–1305. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang L, Wang Y, Zhang L, Xia X, Chao Y, He R, Han C, Zhao W. ZBTB7A, a miR-663a target gene, protects osteosarcoma from endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by suppressing LncRNA GAS5 expression. Cancer Lett. 2019;448:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang EM, Akasaka H, Zhao J, Varadhachary GR, Lee JE, Maitra A, Fleming JB, Hung MC, Wang H, Katz MH. Expression and clinical significance of protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase and phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2019;48:323–328. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yu LM, Dong X, Zhang J, Li Z, Xue XD, Wu HJ, Yang ZL, Yang Y, Wang HS. Naringenin attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via cGMP-PKGIα signaling and in vivo and in vitro studies. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019(7670854) doi: 10.1155/2019/7670854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Peñaranda Fajardo NM, Meijer C, Kruyt FA. The endoplasmic reticulum stress/unfolded protein response in gliomagenesis, tumor progression and as a therapeutic target in glioblastoma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;118:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Beck D, Niessner H, Smalley KS, Flaherty K, Paraiso KH, Busch C, Sinnberg T, Vasseur S, Iovanna JL, Drießen S, et al. Vemurafenib potently induces endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis in BRAFV600E melanoma cells. Sci Signal. 2013;6(ra7) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee JH, Kwon EJ, Kim DH. Calumenin has a role in the alleviation of ER stress in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;439:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brewer JW, Diehl JA. PERK mediates cell-cycle exit during the mammalian unfolded protein response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12625–12630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220247197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang M, Han N, Jiang Y, Wang J, Li G, Lv X, Li G, Qiao Q. EGFR confers radioresistance in human oropharyngeal carcinoma by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling PERK-eIF2α-GRP94 and IRE1α-XBP1-GRP78. Cancer Med. 2018;7:6234–6246. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Palam LR, Baird TD, Wek RC. Phosphorylation of eIF2 facilitates ribosomal bypass of an inhibitory upstream ORF to enhance CHOP translation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10939–10949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Oyadomari S, Koizumi A, Takeda K, Gotoh T, Akira S, Araki E, Mori M. Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:525–532. doi: 10.1172/JCI14550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yao Y, Lu Q, Hu Z, Yu Y, Chen Q, Wang QK. A non-canonical pathway regulates ER stress signaling and blocks ER stress-induced apoptosis and heart failure. Nat Commun. 2017;8(133) doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00171-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Correll RN, Grimes KM, Prasad V, Lynch JM, Khalil H, Molkentin JD. Overlapping and differential functions of ATF6α versus ATF6β in the mouse heart. Sci Rep. 2019;9(2059) doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39515-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Okada T, Yoshida H, Akazawa R, Negishi M, Mori K. Distinct roles of activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) in transcription during the mammalian unfolded protein response. Biochem J. 2002;366:585–594. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yoshida H, Okada T, Haze K, Yanagi H, Yura T, Negishi M, Mori K. ATF6 activated by proteolysis binds in the presence of NF-Y (CBF) directly to the cis-acting element responsible for the mammalian unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6755–6767. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6755-6767.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xiang C, Wang Y, Zhang H, Han F. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in neurodegenerative disease. Apoptosis. 2017;22:1–26. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Korennykh A, Walter P. Structural basis of the unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012;28:251–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tsuru A, Fujimoto N, Takahashi S, Saito M, Nakamura D, Iwano M, Iwawaki T, Kadokura H, Ron D, Kohno K. Negative feedback by IRE1β optimizes mucin production in goblet cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:2864–2869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212484110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pavitt GD, Ron D. New insights into translational regulation in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2012;4(a012278) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Han F, Yan S, Shi Y. Single-prolonged stress induces endoplasmic reticulum-dependent apoptosis in the hippocampus in a rat model of Post-traumatic stress disorder. PLoS One. 2013;8(e69340) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yu B, Wen L, Xiao B, Han F, Shi Y. Single prolonged stress induces ATF6 alpha-dependent Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the apoptotic process in medial Frontal Cortex neurons. BMC Neurosci. 2014;15(115) doi: 10.1186/s12868-014-0115-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Maly DJ, Papa FR. Druggable sensors of the unfolded protein response. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:892–901. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yoshida H. ER stress and diseases. FEBS J. 2007;274:630–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Paschen W. Endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction in brain pathology: Critical role of protein synthesis. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2004;1:173–181. doi: 10.2174/1567202043480125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Thuerauf DJ, Marcinko M, Gude N, Rubio M, Sussman MA, Glembotski CC. Activation of the unfolded protein response in infarcted mouse heart and hypoxic cultured cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2006;99:275–282. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000233317.70421.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Severino A, Campioni M, Straino S, Salloum FN, Schmidt N, Herbrand U, Frede S, Toietta G, Di Rocco G, Bussani R, et al. Identification of protein disulfide isomerase as a cardiomyocyte survival factor in ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Terai K, Hiramoto Y, Masaki M, Sugiyama S, Kuroda T, Hori M, Kawase I, Hirota H. AMP-activated protein kinase protects cardiomyocytes against hypoxic injury through attenuation of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9554–9575. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9554-9575.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Glembotski CC. The role of the unfolded protein response in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hadley G, Neuhaus AA, Couch Y, Beard DJ, Adriaanse BA, Vekrellis K, DeLuca GC, Papadakis M, Sutherland BA, Buchan AM. The role of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response following cerebral ischemia. Int J Stroke. 2018;13:379–390. doi: 10.1177/1747493017724584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lehotský J, Urban P, Pavlíková M, Tatarková Z, Kaminska B, Lehotský J. Molecular mechanisms leading to neuroprotection/ischemic tolerance: Effect of preconditioning on the stress reaction of endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2009;29:917–925. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9376-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Eijkelenboom A, Burgering BM. FOXOs: Signalling integrators for homeostasis maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:83–97. doi: 10.1038/nrm3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Huang H, Tindall DJ. Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2479–2487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chien CT, Lee PH, Chen CF, Ma MC, Lai MK, Hsu SM. De novo demonstration and co-localization of free-radical production and apoptosis formation in rat kidney subjected to ischemia/reperfusion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:973–982. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V125973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Liu H, Wang L, Weng X, Chen H, Du Y, Diao C, Chen Z, Liu X. Inhibition of Brd4 alleviates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury-induced apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress by blocking FoxO4-mediated oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2019;24(101195) doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ren L, Wang Q, Chen Y, Ma Y, Wang D. Involvement of MicroRNA-133a in the protective effect of hydrogen sulfide against ischemia/Reperfusion-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Pharmacology. 2019;103:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000492969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yan Y, Zhang B, Liu N, Qi C, Xiao Y, Tian X, Li T, Liu B. Circulating long noncoding RNA UCA1 as a novel biomarker of acute myocardial infarction. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016(8079372) doi: 10.1155/2016/8079372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chen J, Hu Q, Zhang BF, Liu XP, Yang S, Jiang H. Long noncoding RNA UCA1 inhibits ischaemia/reperfusion injury induced cardiomyocytes apoptosis via suppression of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Genes Genomics. 2019;41:803–810. doi: 10.1007/s13258-019-00806-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Guo R, Ma H, Gao F, Zhong L, Ren J. Metallothionein alleviates oxidative stress-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and myocardial dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Minamino T, Komuro I, Kitakaze M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2010;107:1071–1082. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Glembotski CC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart. Circ Res. 2007;101:975–984. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Chung P, Harding HP, Ron D. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yoneda T, Imaizumi K, Oono K, Yui D, Gomi F, Katayama T, Tohyama M. Activation of caspase-12, an endoplastic reticulum (ER) resident caspase, through tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2-dependent mechanism in response to the ER stress. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13935–13940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Martindale JJ, Fernandez R, Thuerauf D, Whittaker R, Gude N, Sussman MA, Glembotski CC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress gene induction and protection from ischemia/reperfusion injury in the hearts of transgenic mice with a tamoxifen-regulated form of ATF6. Circ Res. 2006;98:1186–1193. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000220643.65941.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Shintani-Ishida K, Nakajima M, Uemura K, Yoshida K. Ischemic preconditioning protects cardiomyocytes against ischemic injury by inducing GRP78. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:1600–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Weigand K, Brost S, Steinebrunner N, Buchler M, Schemmer P, Muller M. Ischemia/Reperfusion injury in liver surgery and transplantation: Pathophysiology. HPB Surg. 2012;2012(176723) doi: 10.1155/2012/176723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hartley T, Siva M, Lai E, Teodoro T, Zhang L, Volchuk A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress response in an INS-1 pancreatic beta-cell line with inducible expression of a folding-deficient proinsulin. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11(59) doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Szegezdi E, Duffy A, O'Mahoney ME, Logue SE, Mylotte LA, O'brien T, Samali A. ER stress contributes to ischemia-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:1406–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Mechanisms underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:581–609. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wang X, Xu L, Gillette TG, Jiang X, Wang ZV. The unfolded protein response in ischemic heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;117:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Yang W, Paschen W. Unfolded protein response in brain ischemia: A timely update. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:2044–2050. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16674488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:184–190. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Li G, Mongillo M, Chin KT, Harding H, Ron D, Marks AR, Tabas I. Role of ERO1-alpha-mediated stimulation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor activity in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:783–792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Timmins JM, Ozcan L, Seimon TA, Li G, Malagelada C, Backs J, Backs T, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Anderson ME, Tabas I. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II links ER stress with Fas and mitochondrial apoptosis pathways. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2925–2941. doi: 10.1172/JCI38857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Vitadello M, Penzo D, Petronilli V, Michieli G, Gomirato S, Menabò R, Di Lisa F, Gorza L. Overexpression of the stress protein Grp94 reduces cardiomyocyte necrosis due to calcium overload and simulated ischemia. FASEB J. 2003;17:923–925. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0644fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ikeda Y, Young LH, Lefer AM. Attenuation of neutrophil-mediated myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by a calpain inhibitor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1421–H1426. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00626.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Hernando V, Inserte J, Sartorio CL, Parra VM, Poncelas-Nozal M, Garcia-Dorado D. Calpain translocation and activation as pharmacological targets during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zheng D, Wang G, Li S, Fan GC, Peng T. Calpain-1 induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in promoting cardiomyocyte apoptosis following hypoxia/reoxygenation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:882–892. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Munoz JP, Ivanova S, Sanchez-Wandelmer J, Martínez-Cristóbal P, Noguera E, Sancho A, Díaz-Ramos A, Hernández-Alvarez MI, Sebastián D, Mauvezin C, et al. Mfn2 modulates the UPR and mitochondrial function via repression of PERK. EMBO J. 2013;32:2348–2361. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zeng L, Liu YP, Sha H, Chen H, Qi L, Smith JA. XBP-1 couples endoplasmic reticulum stress to augmented IFN-beta induction via a cis-acting enhancer in macrophages. J Immunol. 2010;185:2324–2330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Cao L, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Li Y, Zhao P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced NLRP1 inflammasome activation contributes to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Shock. 2019;51:511–518. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Yi YS. Role of inflammasomes in inflammatory autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;22:1–15. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2018.22.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zhang G, Wang X, Gillette TG, Deng Y, Wang ZV. Unfolded protein response as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2019;19:1902–1917. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190521093049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Asada R, Kanemoto S, Kondo S, Saito A, Imaizumi K. The signalling from endoplasmic reticulum-resident bZIP transcription factors involved in diverse cellular physiology. J Biochem. 2011;149:507–518. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zhang K, Shen X, Wu J, Sakaki K, Saunders T, Rutkowski DT, Back SH, Kaufman RJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates cleavage of CREBH to induce a systemic inflammatory response. Cell. 2006;124:587–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Jin JK, Blackwood EA, Azizi K, Thuerauf DJ, Fahem AG, Hofmann C, Kaufman RJ, Doroudgar S, Glembotski CC. ATF6 decreases myocardial ischemia/reperfusion damage and links ER stress and oxidative stress signaling pathways in the heart. Circ Res. 2017;120:862–875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Thuerauf DJ, Hoover H, Meller J, Hernandez J, Su L, Andrews C, Dillmann WH, McDonough PM, Glembotski CC. Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase-2 expression is regulated by ATF6 during the endoplasmic reticulum stress response: Intracellular signaling of calcium stress in a cardiac myocyte model system. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48309–48317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Zhang C, Tang Y, Li Y, Xie L, Zhuang W, Liu J, Gong J. Unfolded protein response plays a critical role in heart damage after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion in rats. PLoS One. 2017;12(e0179042) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Jiang D, Niwa M, Koong AC. Targeting the IRE1α-XBP1 branch of the unfolded protein response in human diseases. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;33:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Schmitz ML, Shaban MS, Albert BV, Gökçen A, Kracht M. The crosstalk of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathways with NF-κB: Complex mechanisms relevant for cancer, inflammation and infection. Biomedicines. 2018;6(58) doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6020058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Ibuki T, Yamasaki Y, Mizuguchi H, Sokabe M. Protective effects of XBP1 against oxygen and glucose deprivation/reoxygenation injury in rat primary hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2012;518:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.DeGracia DJ, Montie HL. Cerebral ischemia and the unfolded protein response. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.McCullough KD, Martindale JL, Klotz LO, Aw TY, Holbrook NJ. Gadd153 sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress by down-regulating Bcl2 and perturbing the cellular redox state. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1249–1259. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1249-1259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]