Abstract

In 2020 we celebrate the bicentennial of the birth of Florence Nightingale and 110 years from her death (1820–1910). This gives us the opportunity to remember her life and her achievements. She is mainly known for her contribution to the foundation of modern nursing in the British Empire and subsequently to the world. Besides her personal engagement in the Crimean War, she organized a professional training for nurses, wrote the first textbook on nursing (“Notes on Nursing”) and took public positions in favor of health care and philanthropic funding. She was a militant for the rights of the women and for social justice. She was a pioneer of medical statistics and hospital management. Her activity is acknowledged worldwide.

Keywords: Florence Nightingale, history of medicine, nursing, women in medicine

This year we celebrate one of the most famous health care providers of the world: Florence Nightingale. Beside representing the “mother” of modern nursing, she was very much engaged in improving the life of war victims, of women and of deprived persons. Considering the importance of this bicentennial, we review here her biography and her work and contributions to medical progress.

Biography

Florence Nightingale was born on May 12, 1820, in Florence, Italy. In her honor, this day will become, starting with 1965, the International Nurses Day. Her name was given by her parents in recognition of the city where they lived at that moment. Florence Nightingale left this world in London on August 13, 1910, after a very intense life filled with many accomplishments [1]. Her youth portrait is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Florence Nightingale, lithographic reproduction of 1857 (private collection).

From the youngest age she developed a strong feeling of philanthropy and expressed the wish to help others. Therefore, she refused the common life path of ladies of that time, rejected advantageous marriage proposals and engaged in the study of nursery against the wish of her family [2,3]. Despite the wish of her parents she insisted and started nursing studies at the level of that time, in Germany. She chose Kaiserwerth, now part of Dusseldorf, where a well-known deaconry run by protestant nuns existed since 1836 thanks to the couple Theodor and Friederike Fliedner [4]. At that time, she could care for patients only in women rooms, while male patients were allocated to male care givers. At night female nurses were not allowed in rooms for male patients. She continued her training in nursing also in France [1,2]. Later she returned to England and since 1853 she worked in a home called the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen [5]. These early years of activity were in fact the prologue of her lifelong work, which started with the onset of the Crimean War.

Participation to the Crimean War and care of wounded and ill soldiers

The so-called Crimean War was in fact a pan-European war in which Russia was confronted with most major European powers contesting tsarist empire spread over Europe to the detriment of Ottoman Empire. The conflict started in 1853 with the occupation of Moldavia and Walachia by Russian troops and spread in Crimea, where the main and bloodiest battles were engaged until the end of 1856. The fights were intense and massive casualties were produced. The British Empire participated to the Crimean War and needed medical service for its army. Florence Nightingale travelled there together with her dedicated staff to care for the wounded on the battlefield and on field hospitals. She became famous for the lamp she always had with her to see the wounded during night, hence her nickname “the lady with the lamp”.

She was an example of enthusiasm and abnegation and motivated her staff (many of them nuns) to take care of those in need in the improvised hospital in Scutari, Turkey, where she worked. There she was able to reduce mortality to 10%. Beside the possibility to actively offer care and support to the victims of war, she drew a few conclusions: the need to organize a nursing system able to provide assistance during war but also during peace; the need to care and protect casualties of the war and prisoners of war. Indeed, everything was missing: hygiene regulations, medicines, skilled assistance, food [6].

In this respect her conception converged very much to that of Henri Dunant, the founder of the Red Cross in 1863, inspired by the terrible impressions of the Solferino battlefield that he visited just after the battle, in 1859.

It is well known that every prominent person has detractors, and the same happened to Florence Nightingale. A Jamaican nurse Mary Seacole claimed over Florence Nightingale the overhand of infirmary care and disputed her merits from the point of view of the negritude movement [1,7].

Founding of modern nursing

Her activity during the Crimean War was well reflected in the contemporary journals and increased the awareness of the need to launch an efficient nursing training and system. Florence Nightingale again was ahead of her time and created in London a nursing school in St Thomas Hospital. She also wrote the “Notes on Nursing”, probably the first textbook on nursing. For her activity she needed and received philanthropic funding.

Soon the Civil War started in the United Stated of America and Florence Nightingale served as an adviser for American nurses. She also trained the first American nurse Linda Richards (1841–1930).

In the following decades, her disciples became important disseminators of the training of Nightingale and contributed to the establishment of a quality nursing in the United Kingdom, which served as an example for other countries as well.

Despite a mysterious disease that disabled her now and again during the second half of the 19th Century (maybe brucellosis?), she remained very much engaged in the care of ill people and in the education of nurses.

Contributions to surgery

Florence Nightingale did not have a direct surgical activity, but dealing with war injuries involves a lot of surgery. Her activity must have included hemostasis, wound cleaning and dressing, prevention of infection. As many health care providers of that time, she was long time not convinced by the existence of pathogenic germs; nevertheless, after the work of Pasteur and others became known, she was cautious in preventing the transmission of infections. She was decisive in the creation of the British Army Medical Service and thus her achievements are a corner stone for military surgery [8]. Therefore she is even now veneered for her personal commitment in war medical health care [9].

Other contributions

Beside nursing and military and civil healthcare she had important contributions to the healthcare system management, to medical statistics, to emancipation of women, for social equality [1]. She emphasized the importance of numbers, i.e. of statistics in healthcare providing: number of beds, number of patients, number of cases etc. [10–12]. These data served her to take decisions in regard to hospital administration and public health measures [13,14]. Her public interventions were always disseminated by journals and were influential for the public health policies of that time.

Cultural echoes

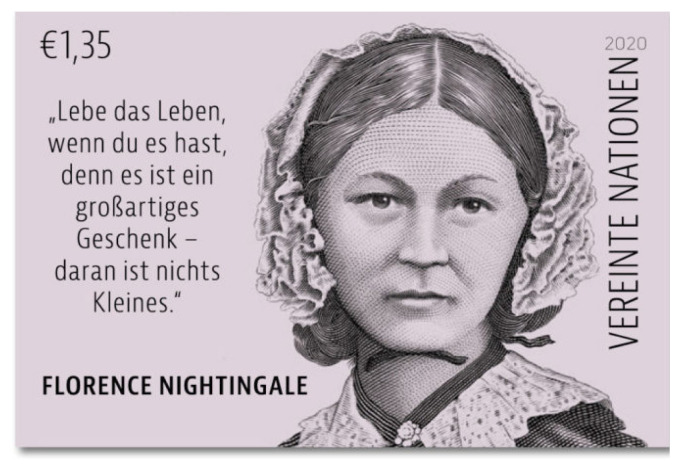

Not only in the United Kingdom, but throughout the world there are hospitals, streets, nursing schools who bear her name. The impact of the life and work of Florence Nightingale is largely reflected on different memorabilia: lithographs (Figure 1), postcards, stamps (Figure 2), coins, etc.

Figure 2.

Stamp issued by United Nations Vienna office on 12 May 2020.

The Florence Nightingale Museum in London contributes to the perpetuation of the personality and achievement of Florence Nightingale. Figure 3 represents a painting from this Museum (published with the kind permission of the Museum director).

Figure 3.

Nursing activity of Florence Nightingale in Scutari Hospital (Florence Nightingale Museum, photograph 2019; with permission of the Museum).

Echoes of Florence Nightingale’s activity in Romania

Most scholars of the history of medicine are familiar in Romania with this name. However, not many know in detail her biography. Unfortunately, there are no monographs dedicated to her to our knowledge.

Some papers about her are in the press, but for general information, not for those with advanced interest in her. Most of them were published in the observation of her bicentennial. One single medical paper indexed in the EBSCO database can be retrieved [1]. Her spirit is however reflected in some papers on nosocomial infections [15].

Conclusions

Florence Nightingale had an enormous contribution to the development of health care. She is indeed the founder of modern scientifically based nursing. Her achievement should be better reflected and disseminated by historians of medicine.

References

- 1.David L, Farcau D, Dumitrascu DL, Rogozea L. Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), the founder of nursing, at the bicentenary. Brasov Med J. 2019;2:72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karimi H, Masoudi Alavi N. Florence Nightingale: The Mother of Nursing. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2015;4:e29475. doi: 10.17795/nmsjournal29475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nightingale F. Cassandra: an essay. 1979. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1586–1587. doi: 10.2105/ajph.100.9.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Die Frau hinter der Legende. [The woman behind the legend]. Darmstadt: wbg Thesis; 2020. Hedwig Herold-Schmidt: Florence Nightingale. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bostridge M. Florence Nightingale: Penguin Books; London: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Small H. A brief history of Florence Nightingale. Little Brown; Book Group: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang TF. Creolizing the white woman’s burden: Mary Seacole playing “mother” at the colonial crossroads between Panama and Crimea. Johns Hopkins Univ Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruse P. Florence Nightingale. J Amer Coll Surg. 1980;88:394–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fee E, Garofalo ME. Florence Nightingale and the Crimean War. Am J Publ Health. 2010;100:1591. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson RJ. Florence Nightingale: the biostatistician. Mol Interv. 2011;11:63–71. doi: 10.1124/mi.11.2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grill E, Müller M. The ICF and Florence Nightingale - bringing data to statistical proof. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:1041–1042. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace DJ, Kahn JM. Florence Nightingale and the Conundrum of Counting ICU Beds. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:2517–2518. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmalbach CE. Patient Safety/Quality Improvement (PS/QI): Florence Nightingale prevails. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:771–773. doi: 10.1177/0194599815577604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis H. Florence Nightingale: nurse and public health officer. Anniversary Bull Hosp Medicine. 2010;71:71. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2010.71.1.45975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ionescu C, Dinu EA, Ercze A, Dobrescu C, Rogozea L, Nemet C. De la infecţia nosocomială la infec cţia asociată actului medical din perspectivă istorică [From nosocomial infection to medical-act-related infection from a historical perspective] Brasov Med J. 2019;1:4–8. [Google Scholar]