Abstract

This study investigated the patterns of antenatal care (ANC) utilization and insufficient use of ANC as well as its association with some proximate socio-demographic factors. This was a cross-sectional study using pooled data Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys from years 2008, 2013 and 2018. Participants were 52,654 women of reproductive age who reported at least one birth in the five years preceding the surveys. The outcome variables were late attendance, first contact after first trimester and less than four antenatal visits using multivariable logistic regression analysis. The overall prevalence of late timing was 74.8% and that of insufficient ANC visits was 46.7%. In the multivariable regression analysis; type of residency, geo-political region, educational level, household size, use of contraceptives, distance to health service, exposure to the media and total number of children were found to be significantly associated with both late and insufficient ANC attendance. About half of the pregnant women failed to meet the recommendation of four ANC visits. Investing on programs to improve women’s socio-economic status, addressing the inequities between urban and rural areas of Nigeria in regard to service utilization, and controlling higher fertility rates may facilitate the promotion of ANC service utilization in Nigeria.

Keywords: antenatal care, maternal health care utilization, global health, Nigeria demographic and health survey

1. Introduction

Despite several efforts by governmental and non-governmental agencies to reduce maternal mortality, maternal deaths remain high globally, particularly in low and middle-income countries (LMIC). Worldwide, about 830 women die from pregnancy or childbirth-related complications every day, and out of the estimated 303,000 maternal deaths in 2015, about 99 percent occurred in LMIC [1]. Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest mortality or morbidity due to reproductive ill-health among pregnant women [2]. The estimated maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015 was 547 per 100,000 live births [1]. With an estimated MMR of 814 per 100,000 live births, Nigeria remains the fourth highest contributor to the region’s maternal deaths and accounts for 19 percent globally [3,4]. Nigeria consists of two percent of the world’s population, but contributes about 10 percent of the worldwide estimates of maternal deaths [5]. In Nigeria, maternal mortality is still relatively high compared to what is obtainable in developed countries, though the ratio reduced to 814 in the year 2015 from 1350 in the year 1990 [3]. In addition, the 2018 Nigeria demographic and health survey reported 512 deaths per 100,000 live births for the seven year period preceding the survey [6].

The Nigerian health care system is poorly developed and health care access is heavily based on out-of-pocket payments. Health resources (for example health centers, personnel, and medical equipment) are inadequate across the country, particularly in rural areas [7]. The Nigerian government established the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) with the aim of improving access to health care and reducing the financial burden of out-of-pocket payments for health care services, but unfortunately a significant proportion of the population, including women, are left out and do not benefit from it [8]. Harrison (1997) highlighted the worsening scenario of maternal mortality in Nigeria subsequent to, and despite, the launch of the Safe Motherhood initiative in 1987. This article focused on three fundamental, although broad, factors underlying the devastating trend in maternal mortality, particularly in Nigeria [1]. These factors are not isolated events that affect maternal mortality but are rather interlinked with several other factors leading to a given trend/result. One research article has shown that poverty, in the absence of appropriate health insurance, leads to the inability of women to seek proper medical care and attention leading to an increase in maternal mortality [3]. Important issues in the efforts towards the reduction of maternal and childhood mortality include the use of maternal health care services [9]. In view of the high level of maternal mortality in Nigeria, despite the efforts of government and non-government institutions, there is a need for more evidence-based research to unveil the factors affecting the use of antenatal care services. Globally, to achieve the third sustainable development goal of reducing maternal deaths to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030, requires more studies [10,11] on effective interventions [9]. Therefore, knowledge and proper understanding of access and demand side factors are important to inform policy. The pertinent question relates to the identification of factors that have contributed to this high maternal mortality and establish whether insufficient antenatal care is one of the factors.

At least 40% of women in LMIC do not receive antenatal care during pregnancy [9]. Whereas utilization of recommended antenatal care has been associated with the reduction of maternal morbidities and mortalities [10]. As a key component of maternal health care services, the timing of antenatal care (ANC) and the numbers of ANC visits are very vital [6]. The use of health facilities has been significantly associated with ANC visits and also sufficient ANC involves both the use of services and the sufficiency of the content within the services [9]. The 2018 Nigeria demographic and health survey reports that only eighteen percent of women had their first ANC visits in the first trimester, which calls for more evidence-based research and approaches to enhance ANC attendance [6].

Similarly, literacy is linked to women’s empowerment, age at marriage and ability to seek health care services [12]. Regarding some of these interlinked factors and following multiple summits and conferences, the United Nations established eight millennium development goals (MDGs), expected to be achieved by 2015. The establishment of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) further underpins the importance of the above interlinked factors. The point underpinning the current study is the relative dearth of studies on the patterns of and predictors of insufficient antenatal care utilization.

Nigeria adhered to WHO’s focused/goal oriented approach or model, also known as the basic ANC model, which includes four ANC visits and was introduced in 2002 for evidence-based intervention for healthy pregnant women [13]. This is designed to compute and explain ANC utilization to policy makers as well as compare countries and monitor ANC coverage. Rationalizing further, WHO stressed the importance of antenatal care towards reducing maternal mortality. Again, several research articles have stressed the importance of “optimal” antenatal care, which acts as a “cornerstone” probably through immunization programs and iron prophylaxis as well as timely identification of pregnancy related risks and complications [14,15,16]. These factors help alleviate maternal mortality and morbidity and reinstate harmonious relationships between pregnant mothers and caregivers including health care provider(s).

Even the earlier introduced Safe Motherhood initiative focused on two crucial strategies, namely improving antenatal care and training birth attendants to reduce maternal mortality [17]. However, evidence has revealed that 70% of the indirect causes of maternal deaths were due to pre-existing disorders exacerbated by pregnancy [18]; and therefore, the role of antenatal care becomes even more critical. Accordingly, the role of antenatal care in reducing maternal mortality and morbidity is evidence-based [19], although it should be noted that there are research articles that debate the importance of antenatal care [20,21]. Additionally, it has been noted that there are disparities in the provision of antenatal care and use, not only inter-country but also inter-region [15,19]. Such disparities and the scarcity of research studies investigating the trend of antenatal care utilization further support the current study. In addition, a number of studies support the fact that both the demand and supply side factors play a role in ANC attendance [22,23,24,25]. It is beyond the scope of the current study to incorporate all of these factors. However, subject to the limitations of data availability, an attempt has been made to incorporate factors that are related to ANC utilization. These do not only aid the comprehension of ANC trends in Nigeria but also provide valuable policy inputs. Therefore, the aim of the study is to investigate the patterns of and predictors of insufficient ANC utilization in Nigeria.

2. Materials and Methods

Data for this study were derived from three rounds of demographic and health surveys (DHS) in Nigeria, which provided information on maternal and child health. In Nigeria, the surveys are implemented by the National Population Commission (NPC) with the financial and technical assistance of Inner-City Fund (ICF) through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded DHS program. DHS surveys collect nationally representative information on a wide range of public health related topics such as anthropometric, demographic and socioeconomic information, family planning and domestic violence. The survey covered men and women aged between 15–49 years and children under 5 residing in non-institutional settings. For sampling, a three-staged stratified cluster design was employed, which was based on a list of enumeration areas (EAs) from the 2006 population census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. The EAs are systematically selected units from the localities, which constitute the local government areas (LGAs). LGAs are subdivisions of each of the 36 administrative states (including the Federal Capital Territory called Abuja) and are classified under six developmental zones in the country. EAs were used to form the survey clusters called primary sampling units. A more detailed version of the survey was published elsewhere [26].

Nigeria is located in the West African sub-region. The country is made up of six regions. Though the most populous country in Africa, it is ravaged by high rates of maternal mortality, mortality of children under 5 years of age, low contraceptive usage, reproductive tract infections, and other maternal morbidity. The health sector generally is characterized by wide regional disparities in status, service delivery, and resource availability. The three tiers of the government in Nigeria (called federal, state and local) share responsibilities for providing health services and programs. Only women who became pregnant or experienced childbirth are eligible to utilize pregnancy care services and were included in this study.

Outcome variables were timing and inadequacy of ANC visits. This was categorized as: (1) first visit after the first trimester, and (2) insufficient ANC visits (less than 4 ANC visits). The timing of an ANC visit was calculated based on the criteria of initiation of the first visit within the first four months of gestation and subsequent visits by the fifth or sixth month [27].

For insufficient ANC visits, the WHO guidelines were used [28,29]—making at least four visits (yes/no). Explanatory variables were based on a broad literature review, and availability of the datasets, and the following variables were included in the analysis: year (2008, 2013 and 2018); age groups (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–45, 45–49); type of place of residence (urban/rural); region (North Central, North East, North, West, South East, South South, South West); education (none, primary, secondary, post-secondary); wealth index (this procedure assigned scores and standardized the wealth indicator variables such as floor type, walls, roof, water source, sanitation facilities, radio, electricity, television, refrigerator, cooking fuel, furniture, number of persons per room); husband’s education (no education, primary, secondary, higher); sex of household head (male/female); total number of children born per household (1–2, 3–4, >4); health insurance (yes/no); use of contraceptives (not using, using); employment status (not working, working); distance to health services (big problem, not a big problem); household size (less than 5, 5+); marriage type (monogamy, polygyny); decision making on health (does not participate, participates) and exposure to the media (yes/no). These variables were selected based on the reports from previous studies [2,11,16,18,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Results are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Operational definition of variables used for analysis.

| Study Variables | Operational Definition and Coding |

|---|---|

| Year | 1 = 2008, 2 = 2013, 3 = 2018 |

| Age | Self-reported ages coded as 1 = 15–19, 2 = 20–24, 3 = 25–29, 4 = 30–34, 5 = 35–39, 6 = 40–44, 7 = 45–49 |

| Regions | Regions of respondents as provided by NDHS *, 1 = North Central, 2 = North East, 3 = North West, 4 = South South, 5 = South East and 6 = South West |

| Type of place of residence | 1 = Urban, 2 = Rural |

| Education | Self-reported 1 = None, 2 = primary, 3 = secondary, 4 = Post-secondary |

| Wealth Index | According to household index classified into 5 categories by NDHS, 1 = Poorest, 2 = Poorer, 3 = Middle, 4 = Richer and Richest |

| Husbands education | 1 = No education, 2 = Primary education, 3 = Secondary education and 4 = Higher |

| Sex of household head | 1 = Male, 2 = Female |

| Total children born | 1 = 1–2, 2 = 3–4 and 3 = >4 |

| Has health insurance | 1= No, 2 = Yes |

| Distance from health services | 1 = Big problem, 2 = Not a big problem |

| Religion | 1 = Christianity, 2 = Islam, 3 = others |

| Use of contraceptive | 1 = Not Using, 2 = Using |

| Employment status | 1 = Not working, 2 = Working |

| Household size | Less than 5, 5+ |

| Decision making on health | 1 = Not participate, 2 = participate |

| Expose to mass media | 0 = No, 1 = Yes |

* NDHS: Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey.

Participants were 52,654 women aged between 15–49 years reporting at least one birth in the five years preceding the surveys. The outcome variables were late attendance (first contact after first trimester) and less than four antenatal visits. The dichotomous nature of each of the categories of the outcome variables informed the use of multivariable logistic regression analysis. Sample weights were divided by 3, applied and used appropriately. Stata version 14 was used to merge datasets, recode variables where necessary and for data analysis. The study considered and used the World Health Organization guidelines, which were published in 2002 and recommended a minimum of 4 ANC visits.

The datasets, which were nationally representative, were from the Nigeria demographic and health surveys. The external validity of the study was enhanced by the standard procedure, the sampling method of DHS and the sample size—which was sufficiently large. Datasets from three surveys (2008, 2013, 2018) were merged into one to perform pooled analysis. Pooled analysis enhances statistical power and the capacity to compare results or outcomes across different periods of time or years. Pooled analysis enhances greater variations in participants, treatments, and subgroup analyses in the pooled dataset. To adjust for the cluster sampling technique of the surveys, we used complex survey modules for all analysis by accounting for primary sampling units, sample strata and sample weight. Following that, descriptive analyses were carried out to calculate the prevalence rates of insufficient utilization of ANC. Chi-square tests were performed to examine the bi-variate association between insufficient ANC and the socio-demographic variables. Variables that were found to be significant at alpha 5% were entered into the multiple regression analysis [35]. Binary logistic regression analyses were carried out to calculate the odds ratios of the association between two outcome measures with the socio-demographic variables. The level of significance was set at alpha 5% for the regression model. Computation of wealth index was obtained through DHS using principal components analysis (PCA) to assign the wealth indicator weights. Thereafter, the factor coefficient scores (factor loadings), and z-scores were calculated. Finally, for each household, the indicator values were multiplied by the loadings and summed to produce the household’s wealth index value. The standardized z-score was used to disentangle the overall assigned scores and to classify the scores as poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest.

The analyses were done using publicly available data from demographic health surveys. Ethical procedures were the responsibility of the institutions that commissioned, funded, or managed the surveys. All DHS surveys have been approved by ICF International as well as an institutional review board (IRB) in Nigeria to ensure that the protocols are in compliance with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects (http://dhsprogram).

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes the socio-demographic description of the participants. Mean age was 29.6. Most of the respondents were: adherents of Islam (61.9%), living in rural areas (65.2%), working (67.8%), belonged to a monogamous family type (68.3%), did not participate in health decision making (61.0%), had access to health facility (67.5%), did not use contraceptives (88.9%), from male-headed households (92.5%), had no health insurance (98.2%), not exposed to the media/family planning information through the media (65.0%) and about half had no formal education (48.1%).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic profile of the sample population, socio-demographic patterns in the uptake of antenatal care (ANC) services, Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) 2008–2018.

| Variables | N (52,654) | % | Contact after 1st Trimester (n = 26,407) 74.8% (95% CI = 74.4, 75.3) |

p-Value | Less than 4 Attendances (n = 24,576) 46.7% (95% CI = 46.2, 47.1) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||||

| 2008 | 14,475 | 27.5 | 74.0 (73.1–74.9) | 50.5 (49.7–51.3) | ||

| 2013 | 18,214 | 34.6 | 73.5 (72.7–74.3) | 0.001 | 48.2 (47.4–48.9) | 0.001 |

| 2018 | 19,964 | 37.9 | 76.3 (75.6–76.9) | 42.5 (41.8–43.2) | ||

| Age groups | ||||||

| 15–19 | 3060 | 5.8 | 4.6 (4.4–4.9) | 07.7 (07.4–08.0) | ||

| 20–24 | 9936 | 18.9 | 17.8 (17.3–18.3) | 0.009 | 20.6 (20.1–21.2) | 0.001 |

| 25–29 | 13,913 | 26.4 | 27.0 (26.5–27.6) | 25.6 (25.0–26.1) | ||

| 30–34 | 11,285 | 21.4 | 22.3 (21.8–22.8) | 18.7 (18.2–19.2) | ||

| 35–39 | 8423 | 16.0 | 16.8 (16.3–17.2) | 14.9 (14.4–15.3) | ||

| 40–44 | 4257 | 8.1 | 8.3 (8.0–8.6) | 08.4 (08.0–8.7) | ||

| 45–49 | 1781 | 3.4 | 3.2 (3.0–3.4) | 04.1 (03.9–04.4) | ||

| Religion | ||||||

| Christian | 19,522 | 37.1 | 46.0 (45.4–46.6) | 22.9 (22.4–23.4) | ||

| Islam | 32,600 | 61.9 | 53.1 (52.5–53.7) | 0.001 | 75.4 (74.9–75.9) | 0.001 |

| Others | 532 | 1.0 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 01.7 (01.5–01.9) | ||

| Type of place of residence | ||||||

| Urban | 18,350 | 34.8 | 41.8 (41.2–42.4) | 15.7 (15.2–16.1) | ||

| Rural | 34,304 | 65.2 | 58.2 (57.6–58.8) | 0.992 | 84.3 (83.9–84.8) | 0.001 |

| Region | ||||||

| North Central | 7484 | 14.2 | 16.7 (16.3–17.2) | 15.0 (14.6–15.5) | ||

| North East | 9237 | 17.5 | 20.7 (20.2–21.2) | 0.001 | 27.4 (26.8 –27.9) | 0.001 |

| North West | 18,786 | 35.7 | 23.7 (23.2–24.2) | 44.6 (43.9–45.2) | ||

| South East | 4330 | 8.2 | 11.1 (10.8–11.5) | 02.9 (02.7–03.1) | ||

| South South | 4778 | 9.1 | 11.1 (10.7–11.5) | 07.4 (07.1–07.7) | ||

| South West | 8040 | 15.3 | 16.7 (16.2–17.1) | 02.8 (02.6–03.0) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| None | 25,328 | 48.1 | 34.7 (34.2–35.3) | 71.8 (71.3–72.4) | ||

| Primary | 9576 | 18.2 | 22.4 (21.9–23.0) | 0.001 | 15.3 (14.9–15.8) | 0.001 |

| Secondary | 14,053 | 26.7 | 34.2 (33.6–34.8) | 11.8 (11.4–12.2) | ||

| Post-secondary | 3697 | 7.0 | 8.6 (8.3–9.0) | 01.0 (00.9–01.2) | ||

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poorest | 12,475 | 23.7 | 14.8 (14.4–15.2) | 40.5 (39.9–41.1) | ||

| Poorer | 11,860 | 22.5 | 19.7 (19.3–20.2) | 0.001 | 30.0 (29.5–30.6) | 0.001 |

| Middle | 9965 | 18.9 | 22.4 (21.9–22.9) | 16.9 (16.4–17.4) | ||

| Richer | 9305 | 17.7 | 23.3 (22.8–23.8) | 09.3 (09.0–09.7) | ||

| Richest | 9048 | 17.2 | 19.8 (19.3–20.3) | 03.2 (03.0–03.5) | ||

| Employment Status | ||||||

| Not working | 16,941 | 32.2 | 28.4 (27.8–28.9) | 40.6 (39.9–41.2) | ||

| Working | 35,713 | 67.8 | 71.6 (71.1–72.2) | 0.001 | 59.4 (58.8–60.1) | 0.001 |

| Husbands education | ||||||

| None | 20,350 | 38.6 | 25.3 (24.8–25.8) | 60.5 (59.9–61.1) | ||

| Primary | 9229 | 17.5 | 20.0 (19.6–20.5) | 0.001 | 15.8 (15.3–16.2) | 0.001 |

| Secondary | 16,118 | 30.6 | 37.5 (36.9–38.0) | 18.5 (18.0–19.0 | ||

| Higher | 6957 | 13.2 | 17.2 (16.8–17.7) | 05.2 (05.0–05.5) | ||

| Marriage type | ||||||

| Monogamy | 35,985 | 68.3 | 71.8 (71.3–72.4) | 60.0 (59.4–60.6) | ||

| Polygyny | 16,669 | 31.7 | 28.2 (27.6–28.7) | 0.001 | 40.0 (39.4–40.6) | 0.001 |

| Sex of household head | ||||||

| Male | 48,679 | 92.5 | 90.7 (90.3–91.3) | 94.6 (94.3–94.9) | ||

| Female | 3975 | 7.5 | 9.3 (8.6–9.7) | 0.062 | 05.4 (05.1–05.7) | 0.001 |

| Total children ever born | ||||||

| 1–2 | 17,371 | 33.0 | 32.8 (32.2–33.4) | 28.2 (27.6–28.7) | ||

| 3–4 | 15,124 | 28.7 | 29.8 (29.3–30.4) | 0.001 | 26.7 (26.2–27.3) | 0.001 |

| >4 | 20,159 | 38.3 | 37.4 (36.8–38.0) | 45.1 (44.5–45.7) | ||

| Household Size | ||||||

| Less than 5 | 22,952 | 43.6 | 44.1 (43.5–44.7) | 36.3 (35.7–36.9) | ||

| 5+ | 29,702 | 56.4 | 55.9 (55.3–56.5) | 0.062 | 63.7 (63.1–64.3) | 0.001 |

| Health Decision Making | ||||||

| Not participate | 32,115 | 61.0 | 54.5 (53.9–55.1) | 74.3 (73.8–74.8) | ||

| Participate | 20,539 | 39.0 | 45.5 (44.9–46.1) | 0.001 | 25.7 (25.2–26.2) | 0.001 |

| Distance to health service | ||||||

| Big problem | 17,113 | 32.5 | 26.0 (25.4–26.5) | 45.3 (44.7–46.0) | ||

| Not a big problem | 35,541 | 67.5 | 74.0 (73.5–74.6) | 0.027 | 54.7 (54.0–55.3) | 0.001 |

| Use of contraceptive | ||||||

| Not Using | 46,824 | 88.9 | 86.2 (85.8–86.7) | 95.6 (95.3–95.8) | ||

| Using | 5830 | 11.1 | 13.8 (13.3–14.2) | 0.001 | 04.4 (04.2–04.7) | 0.001 |

| Has health insurance | ||||||

| No | 51,716 | 98.2 | 97.6 (97.4–97.8) | 99.5 (99.4–99.6) | ||

| Yes | 938 | 1.8 | 2.4 (2.2–2.6) | 0.001 | 00.5 (00.4–00.6) | 0.001 |

| Exposure to Media | ||||||

| No | 34,254 | 65.0 | 59.4 (58.8–60.0) | 0.001 | 81.6 (81.1–82.0) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 18,400 | 35.0 | 40.6 (40.0–41.2) | 18.4 (18.0–18.9) |

3.2. Timing of ANC Visits

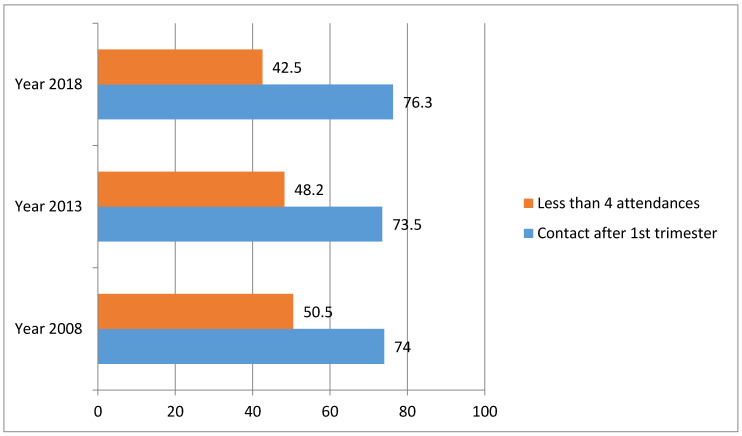

Overall, out of the 52,654 respondents, 24,576 attended less than four ANC visits while out of 35,300 women who sought ANC, 26,407 went after the first trimester. As shown in Table 2, the overall prevalence of late timing was 74.8% (95% CI = 74.4–75.3). The prevalence of women who attended less than a minimum of four ANC visits was 46.7% (95% CI = 46.2–47.1). While there had been a marginal decrease in the prevalence of late ANC visits between 2008 and 2013, an increase was observed between 2013 and 2018. A decrease in the prevalence of women who attended less than a minimum of four ANC visits was observed between 2008 and 2013, and also between 2013 and 2018. Details on the timing of ANC visits are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patterns of insufficient antenatal care. Utilization in Nigeria.

The table also indicates that the rate of late contact was higher among women who were: between 25–29 years of age, residents of rural and northwest regions, followers of Islam, had formal education, lived in richer households, husbands had secondary education, working, belonged to a monogamous marriage type, had >4 household members, did not participate in making decisions on health, had problems accessing health services, did not use contraceptives, exposed to the media, had >4 children, male headed households and had no health insurance while higher patterns were observed for insufficient ANC visits among women 25–29 years of age, residents of rural and northwest regions, followers of Islam, with no formal education, working, belonged to monogamous marriage type, had >4 household members, did not participate in making decisions on health, had problem accessing health services, did not use contraceptives, not exposed to the media, belonged to poorest household category, husbands had no formal education, male headed households, had >4 children and had no health insurance.

3.3. Odds of Late ANC Contacts

The results of multivariable regression analysis (Table 3) on the association between utilization of ANC and the socio-demographic variables are summarized in Table 3. The odds ratios of late contacts were significantly higher among women in the North East (OR 1.68; 95% CI 1.55–1.82), South South (OR 2.00; 95% CI 1.82–2.20), South East (OR 1.37; 95% CI 1.24–1.50), South West (OR 1.67; 95% CI 1.53–1.81), and North West (OR 2.97; 95% CI 2.70–3.25) compared with North Central; among those who had more than four children (OR 1.27; 95% CI 1.16–1.39) or 3–4 children (OR 1.16; 95% CI 1.08–1.24) compared with those who had 1–2 children, among female headed households (OR 1.11; 95% CI 1.02–1.21) compared with those households headed by a male; among households with more than four members (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.12–1.27) compared with households with four/less than four members and lower in the rural (OR 0.79; 95% CI 0.74–0.84) areas compared with urban areas, among those who had secondary education (OR 0.92; 95% CI 0.84–1.00) and post-secondary education (OR 0.76; 95% CI 0.67–0.86) compared with those with no formal education; among those who claimed their husbands had secondary education (OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.82–0.98) and post-secondary education (higher) (OR 0.84; 95% CI 0.76–0.93) compared with women who claimed their husbands had no formal education; among those who were working (OR 0.89; 95% CI 0.84–0.95) compared with women who were not working, among women who claimed distance was a big problem to accessing health facilities (OR 0.93; 95% CI 0.88–0.99) compared with women who claimed distance was not a big problem and among women who were using contraceptives (OR 0.92; 95% CI 0.86–0.98) compared to those who were not using contraceptives.

Table 3.

Predictors of inadequate use of ANC services in Nigeria, NDHS 2008–2018.

| Variables | Contact After 1st Trimester (n = 26,407) | Less than Four Visits (n = 24,576) |

|---|---|---|

| Year | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| 2008 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| 2013 | 0.90 (0.85–97) ** | 0.82 (0.78–0.87) *** |

| 2018 | 1.05 (0.99–1.12) | 0.72 (0.68–0.76) *** |

| Age Groups | ||

| 15–19 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| 20–24 | 0.93 (0.81–1.06) | 0.89 (0.81–0.99) * |

| 25–29 | 0.95 (0.83–1.09) | 0.81 (0.73–0.90) *** |

| 30–34 | 0.88 (0.76–1.02) | 0.68 (0.61–0.76) *** |

| 35–39 | 0.87 (0.75–1.02) | 0.69 (0.61–0.78) *** |

| 40–44 | 0.85 (0.72–1.01) | 0.66 (0.58–0.75) *** |

| 45–49 | 0.89 (0.72–1.10) | 0.69 (0.59–0.81) *** |

| Religion | ||

| Christian | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Islam | 1.17 (1.10–1.26) *** | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) |

| Others | 1.22 (0.93–1.62) | 1.52 (1.25–1.84) *** |

| Type of place of residence | ||

| Urban | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Rural | 0.79 (0.74–0.84) *** | 1.23 (1.16–1.30) *** |

| Region | ||

| North Central | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| North East | 1.68 (1.55–1.82) *** | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) |

| North West | 2.97 (2.70–3.25) *** | 1.73 (1.62–1.86) *** |

| South East | 1.37 (1.24–1.50) *** | 0.54 (0.48–0.60) *** |

| South South | 2.00 (1.82 = 2.20) *** | 1.62 (1.48–1.76) *** |

| South West | 1.67 (1.53–1.81) *** | 0.39 (0.36–0.44) *** |

| Education | ||

| None | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Primary | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | 0.66 (0.62–0.70) *** |

| Secondary | 0.92 (0.84–1.00) * | 0.54 (0.50–0.58) *** |

| Post-secondary | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) *** | 0.34 (0.29–0.40) *** |

| Wealth index | ||

| Poorest | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Poorer | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) | 0.69 (0.64–0.73) *** |

| Middle | 0.98 (0.88–1.08) | 0.49 (0.46–0.53) *** |

| Richer | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) | 0.42 (0.38–0.45) *** |

| Richest | 0.88 (0.78–0.99) * | 0.27 (0.24–0.31) *** |

| Employment Status | ||

| Not working | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Working | 0.89 (0.84–0.95) *** | 0.82 (0.78–0.86) *** |

| Husbands education | ||

| None | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Primary | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) | 0.59 (0.55–0.62) *** |

| Secondary | 0.90 (0.82–0.98) * | 0.56 (0.52–0.59) *** |

| Higher | 0.84 (0.76–0.93) ** | 0.49 (0.45–0.54) *** |

| Marriage type | ||

| Monogamy | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Polygyny | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) |

| Sex of household head | ||

| Male | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Female | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) * | 0.95 (0.87–1.03) |

| Total children ever born | ||

| 1–2 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| 3–4 | 1.16 (1.08–1.24) *** | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) *** |

| >4 | 1.27 (1.16–1.39) *** | 1.30 (1.0–1.40) *** |

| Household Size | ||

| Less than 5 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| 5+ | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) *** | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) * |

| Health Decision Making | ||

| Not participate | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Participate | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 0.82 (0.78–0.86) *** |

| Distance to health service | ||

| Big problem | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Not a big problem | 0.93 (0.88–0.99) * | 0.58 (0.55–0.61) *** |

| Use of contraceptive | ||

| Not Using | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Using | 0.92 (0.86–0.98) * | 0.67 (0.62–0.72) *** |

| Has health insurance | ||

| No | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 0.92 (0.79–1.06) | 0.68 (0.55.0.85) ** |

| Exposure to Media | ||

| No | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Yes | 0.95 (0.89–1.00) * | 0.68 (0.65–0.71) *** |

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

3.4. Odds of Less than Four ANC Visits

In general, the odds ratios of less than a minimum of four visits were higher among rural residences (OR 1.23; 95% CI 1.16–1.30) compared with urban residences, among women in the North West (OR 1.73; 95% CI 1.62–1.86) and South South (OR 1.62; 95% CI 1.48–1.76) compared with North Central, among those who had more than four children (OR 1.30; 95% CI 1.20–1.40) or 3–4 children (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.12–1.27) compared with those who had 1–2 children and among households with five or more members (OR 1.07; 95% CI 1.01–1.13) compared with households with less than five members while the odds ratios of less than a minimum of four visits were lower among those in the older age groups (20–24 (OR 0.89; 95% CI 0.81–0.99), 25–29 (OR 0.81; 95% CI 0.73–0.90), 30–34 (OR 0.68; 95% CI 0.61–0.76); 35–39 (OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.61–0.78), 45–49 (OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.59–0.81) and 40–44 (OR 0.66; 95% CI 0.58–0.75)) compared with those in the youngest age group (15–19 years). The associations of less than four ANC visits were negative in some regions (South West (OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.36–0.44) and South East (OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.48,–0.60)), educational status among the respondents (primary (OR 0.66; 95% CI 0.62–0.70), secondary (OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.50–0.58) and post-secondary education (OR 0.34; 95% CI 0.29–0.40)), and husband’s education (primary (OR 0.59; 95% CI 0.55–0.62), secondary (OR 0.56; 95% CI 0.52–0.59), higher (OR 0.49; 95% CI 0.45–0.54)), household wealth status (poorer (OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.64–0.73), middle (OR 0.49; 95% CI 0.46–0.53), richer (OR 0.42; 95% CI 0.38–0.45) and richest (OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.24–0.31)), employment status (working (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.78–0.86)), having health insurance (OR 0.68; 95% CI 0.55–0.85), health decision making (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.78–0.86), having exposure to the media (OR 0.68; 95% CI 0.65–0.71) and using contraceptives (OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.62–0.72).

4. Discussion

The study considered datasets from three Nigeria demographic and health surveys (2008, 2013 and 2018). The datasets were merged into one to perform pooled analysis. Unlike several other related studies [4,9,10,19,29,30,31,33,36], this study enjoyed the benefits of pooled analyses. Pooled analysis enhanced variations in participants, treatments, statistical power, and comparison of outcomes across different years. There was little or no reduction in the late ANC visits and insufficient attendance over time, 2008 to 2018. The evidence revealed an association between the increased use of pre-natal health care services and the socio-economic status of women [37]. Overall, the majority of the participants reported late ANC visits and also insufficient attendance. A marginal decrease was observed in late ANC visits between 2008 and 2013 but an increase was observed between 2013 and 2018 while a decrease was observed with respect to insufficient attendance between 2008 and 2018.

The late ANC visits and insufficient attendance are serious issues of concern in Nigeria. Socio-economic factors of women play a significant role in determining the utilization of antenatal health care services. Intervention policies and programs should address socio-economic vulnerabilities to reduce under-utilization of antenatal care services [5,37,38]. The poor attendance might be connected with the high maternal and child mortalities in the country [39]. A large percentage of the maternal mortality in sub-Saharan countries [11] stemmed from Nigeria. With the high percentage of late ANC visits and insufficient ANC attendance, much needed to be achieved in Nigeria to achieve the third sustainable development goal, that is, good health and well-being for all [40]. With more studies (on determinants of access and demand, as people have to access facility before they enjoy its content), health facilities and various intervention programs, a reduction in late ANC visits and insufficient attendance is expected.

The older women were more sensitive to ANC utilization. The likelihood of insufficient ANC visits was more common among the younger cohorts of women when compared with the older age group. A similar pattern was observed for ANC visits after the first trimester (late ANC visit) among the women. Those living in rural areas, compared to urban areas, were less likely to make at least four ANC visits but more likely to avoid attending ANC visits late in the first trimester. Many of the health facilities in Nigeria are situated in urban areas and they are accessible. Effective policies to address rural–urban differentials in this regard is a requirement for better ANC health care services [41]. In the same vein, regional disparities were noted in the underutilization of ANC services. Disparities in the underutilization of ANC services might be connected with regional disparities in socio-demographic factors such as education, wealth status, age and employment [37]. Improvement in social services through socio-economic and health policy interventions may help to reduce regional disparities in the underutilization of ANC in Nigeria [38].

In addition to the level of secondary or higher education of the women [40], their husband’s level of secondary or higher education can also influence the likelihood of late ANC attendance [29] in the first trimester of pregnancy as well as less than four ANC visits [5]. Therefore, investment in female education may enhance early initiation of ANC visits [37]. Education affords women better access to health care information and the ability to participate in decision making about health care services and also the capacity to understand the negative consequences of not utilizing prenatal health care services [37,42]. For wealth index quintiles comparison with the poorest quintile, the higher the wealth index quintile, the lower the likelihood of less than four ANC visits. This finding is consistent with findings from similar previous studies on the economic status of women and its positive influence on prenatal care service utilization [37,43,44]. It should be noted, however, that the findings for education level, region of residence and wealth index quintiles were not monotonic. Findings from this study reveal that the increasing level of education from primary to secondary, for example, decreases the relative likelihood of insufficient ANC utilization. Several research studies have noted multiple factors that play a role in ANC utilization and the most important of these are residence [32,36], regional disparities, economic disparities and education level [5,32,37]. These findings are consistent across multiple studies and across multiple countries [27,34,45,46,47,48,49].

As discussed above, employment status, number of children, distance to health service [5,50] and use of contraceptives also influenced ANC utilization. In addition, having health insurance influenced the frequency of ANC visits. Health insurance reduced out-of-pocket payments for drugs and other ANC services and thus encouraged ANC attendance. Exposure to family planning information through the media afforded the women the opportunity to receive information and counselling about the need for ANC utilization. This explained the association found between exposure to the media and ANC utilization. These findings are again consistent with previous research studies [37,51,52,53,54]. Overall, women in Nigeria have not achieved the old WHO guideline of a minimum of four ANC visits. Achievement of the new WHO guideline of a minimum of eight ANC visits may be a mirage in the short term. Therefore, to improve the use of ANC and reduce the negative outcomes, such as maternal morbidity and mortality, program administrators and policy makers should address socio-demographic vulnerabilities of women.

This study included a large sample from three representative surveys to measure the prevalence of late and insufficient ANC visits among women aged 15–49 years. Data were analyzed taking into consideration the cluster effects to ensure the precision of the estimates. Women from both urban and rural areas were included, across all six regions, which increases the external validity of the findings. Nonetheless, the surveys were cross-sectional and hence the associations do not equate to causations. The study did not consider the new WHO guideline of a minimum of eight ANC visits because two out of the three waves of the datasets used (2008 and 2013 Nigeria demographic and health surveys) were released before the new recommendation and for ease of comparison with similar studies. The study addressed only ANC utilization and not quality of care received. There is a need for further qualitative study to deepen knowledge and understanding of barriers to ANC uptake. In addition, identification of more successful interventions through implementation research may help to improve the uptake of ANC.

5. Conclusions

Based on the analysis of three rounds of DHS surveys, this study shows that the prevalence of late timing of ANC and insufficient ANC attendance remained high despite the different efforts to ensure prompt and sufficient attendance. The high occurrence of late timing and insufficient attendance threatens health development in Nigeria and the achievement of the sustainable development goals for maternal and child health. To reduce maternal and child morbidity and mortality, policy makers should make efforts to improve prompt and timely ANC attendance among women in Nigeria. Furthermore, lower educational level, residence, geographical region, household size, use of contraceptives, poor household wealth status, and having more than two children also appeared to be associated with insufficient utilization of ANC services. These findings highlight the need for investing in improving women’s socio-economic status as a potential strategy to promote the utilization of ANC services in the country.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the MEASURE DHS project for their support and for free access to the original data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.Y.; methodology, S.Y.; software, S.Y., E.K.O., Z.E.-K. and B.G.; validation, S.Y., E.K.O., Z.E.-K. and B.G.; software, S.Y., E.K.O., Z.E.-K. and B.G.; formal analysis, S.Y., E.K.O., Z.E.-K. and B.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.Y., E.K.O., Z.E.-K. and B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

No competing interest among the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015. [(accessed on 13 April 2020)]; Available online: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/maternal-mortality-2015/en/

- 2.Ogundele O.J., Pavlova M., Groot W. Examining trends in inequality in the use of reproductive health care services in Ghana and Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:492. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Countries with the Highest Maternal Mortality Rates—WorldAtlas.com. [(accessed on 13 April 2020)]; Available online: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/countries-with-the-highest-maternal-mortality-rates.html.

- 4.Aliyu A.A., Dahiru T. Predictors of delayed Antenatal Care (ANC) visits in Nigeria: Secondary analysis of 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) Pan Afr. Med. J. 2017;26:124. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.26.124.9861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abimbola J.M., Makanjuola A.T., Ganiyu S.A., Babatunde U.M.M., Adekunle D.K., Olatayo A.A. Pattern of utilization of ante-natal and delivery services in a semi-urban community of North-Central Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2016;16:962–971. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v16i4.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Npc N.P.C. ICF Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018—Final Report. [(accessed on 19 March 2020)];2019 Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr359-dhs-final-reports.cfm.

- 7.Welcome M.O. The Nigerian health care system: Need for integrating adequate medical intelligence and surveillance systems. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2011;3:470–478. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.90100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olakunde B.O. Public health care financing in Nigeria: Which way forward? Ann. Niger. Med. 2012;6:4. doi: 10.4103/0331-3131.100199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Awotunde O.T., Amole I.O., Adesina S.A., Adeniran A., OlaOlorun D.A., Durodola A.O., Awotunde T.A. Pattern of Antenatal Care Services Utilization in a Mission Hospital in Ogbomoso South-west Nigeria. J. Adv. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2019:1–11. doi: 10.9734/jamps/2019/v21i230127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali N., Sultana M., Sheikh N., Akram R., Mahumud R.A., Asaduzzaman M., Sarker A.R. Predictors of Optimal Antenatal Care Service Utilization Among Adolescents and Adult Women in Bangladesh. Health Serv. Res. Manag. Epidemiol. 2018;5:2333392818781729. doi: 10.1177/2333392818781729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akinyemi J.O., Bolajoko I., Gbadebo B.M. Death of preceding child and maternal healthcare services utilisation in Nigeria: Investigation using lagged logit models. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2018;37:23. doi: 10.1186/s41043-018-0154-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison K.A. Maternal Mortality in Nigeria: The Real Issues. Afr. J. Reprod. Health Rev. Afr. Santé Reprod. 1997;1:7–13. doi: 10.2307/3583270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogel J.P., Habib N.A., Souza J.P., Gülmezoglu A.M., Dowswell T., Carroli G., Baaqeel H.S., Lumbiganon P., Piaggio G., Oladapo O.T. Antenatal care packages with reduced visits and perinatal mortality: A secondary analysis of the WHO Antenatal Care Trial. Reprod. Health. 2013;10:19. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Role of Female Literacy in Maternal and Infant Mortality Decline—Alpana Kateja. [(accessed on 13 April 2020)];2007 Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/004908570703700202?journalCode=scha.

- 15.Lanre-Abass B.A. Poverty and maternal mortality in Nigeria: Towards a more viable ethics of modern medical practice. Int. J. Equity Health. 2008;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inam S.N.B., Khan S. Importance of antenatal care in reduction of maternal morbidity and mortality. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2002;52:137–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.EBCOG Scientific Committee The Public Health Importance of Antenatal Care. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn. 2015;7:5–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Role of Antenatal Care in Reducing Maternal Mortality—Pandit—1992—Asia-Oceania Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology—Wiley Online Library. [(accessed on 13 April 2020)]; doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1992.tb00291.x. Available online: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1447-0756.1992.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Jacobs C., Moshabela M., Maswenyeho S., Lambo N., Michelo C. Predictors of Antenatal Care, Skilled Birth Attendance, and Postnatal Care Utilization among the Remote and Poorest Rural Communities of Zambia: A Multilevel Analysis. Front. Public Health. 2017;5:11. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nour N.M. An Introduction to Maternal Mortality. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;1:77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan K.S., Wojdyla D., Say L., Gülmezoglu A.M., Van Look P.F. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: A systematic review. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2006;367:1066–1074. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDonagh M. Is antenatal care effective in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality? Health Policy Plan. 1996;11:1–15. doi: 10.1093/heapol/11.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexander G.R., Kotelchuck M. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: History, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:306–316. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50052-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pell C., Meñaca A., Were F., Afrah N.A., Chatio S., Manda-Taylor L., Hamel M.J., Hodgson A., Tagbor H., Kalilani L., et al. Factors Affecting Antenatal Care Attendance: Results from Qualitative Studies in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yaya S., Bishwajit G., Ekholuenetale M., Shah V., Kadio B., Udenigwe O. Timing and adequate attendance of antenatal care visits among women in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0184934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.NPC/Nigeria N.P.C., International I.C.F. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. [(accessed on 19 March 2020)];2014 Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr293-dhs-final-reports.cfm.

- 27.Ononokpono D.N., Azfredrick E.C. Intimate partner violence and the utilization of maternal health care services in Nigeria. Health Care Women Int. 2014;35:973–989. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.924939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotoh A.M., Boah M. “No visible signs of pregnancy, no sickness, no antenatal care”: Initiation of antenatal care in a rural district in Northern Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1094. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7400-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Islam M.M., Masud M.S. Determinants of frequency and contents of antenatal care visits in Bangladesh: Assessing the extent of compliance with the WHO recommendations. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0204752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rurangirwa A.A., Mogren I., Nyirazinyoye L., Ntaganira J., Krantz G. Determinants of poor utilization of antenatal care services among recently delivered women in Rwanda; a population based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:142. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1328-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ewunetie A.A., Munea A.M., Meselu B.T., Simeneh M.M., Meteku B.T. DELAY on first antenatal care visit and its associated factors among pregnant women in public health facilities of Debre Markos town, North West Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:173. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1748-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolde F., Mulaw Z., Zena T., Biadgo B., Limenih M.A. Determinants of late initiation for antenatal care follow up: The case of northern Ethiopian pregnant women. BMC Res. Notes. 2018;11:837. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3938-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manyeh A.K., Amu A., Williams J., Gyapong M. Factors associated with the timing of antenatal clinic attendance among first-time mothers in rural southern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:47. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-2738-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fagbamigbe A.F., Idemudia E.S. Wealth and antenatal care utilization in Nigeria: Policy implications. Health Care Women Int. 2017;38:17–37. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2016.1225743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munguambe K., Boene H., Vidler M., Bique C., Sawchuck D., Firoz T., Makanga P.T., Qureshi R., Macete E., Menéndez C., et al. Barriers and facilitators to health care seeking behaviours in pregnancy in rural communities of southern Mozambique. Reprod. Health. 2016;13:31. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0141-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul P., Chouhan P. Socio-demographic factors influencing utilization of maternal health care services in India. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 2020;8:666–670. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2019.12.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogbo F.A., Dhami M.V., Ude E.M., Senanayake P., Osuagwu U.L., Awosemo A.O., Ogeleka P., Akombi B.J., Ezeh O.K., Agho K.E. Enablers and Barriers to the Utilization of Antenatal Care Services in India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2019;16:3152. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16173152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ugalahi L.O., Yusuf O.B., Akinyemi J.O., Adebowale A.S. Regional Differences in the Optimal Utilisation of Antenatal Care in Nigeria. Sci. J. Public Health. 2016;4:43. doi: 10.11648/j.sjph.20160401.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiwani S.S., Amouzou-Aguirre A., Carvajal L., Chou D., Keita Y., Moran A.C., Requejo J., Yaya S., Vaz L.M., Boerma T. Timing and number of antenatal care contacts in low and middle-income countries: Analysis in the Countdown to 2030 priority countries. J. Glob. Health. 2020;10 doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Babalola B.I. Determinants of urban-rural differentials of antenatal care utilization in Nigeria. Afr. Popul. Stud. 2014;28:1263–1273. doi: 10.11564/0-0-614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahoo J., Singh S.V., Gupta V.K., Garg S., Kishore J. Do socio-demographic factors still predict the choice of place of delivery: A cross-sectional study in rural North India. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 2015;5:S27–S34. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simkhada B., van Teijlingen E.R., Porter M., Simkhada P. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: Systematic review of the literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008;61:244–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Godha D., Hotchkiss D.R., Gage A.J. Association between child marriage and reproductive health outcomes and service utilization: A multi-country study from South Asia. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2013;52:552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olabisi J.O., Olabisi O.A., Dairo D.M. Utilization of Antenatal Care in Nigeria—An analysis of Patterns and Trends from 1999–2008. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015;44:i47. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv097.181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuuire V.Z., Kangmennaang J., Atuoye K.N., Antabe R., Boamah S.A., Vercillo S., Amoyaw J.A., Luginaah I. Timing and utilisation of antenatal care service in Nigeria and Malawi. Glob. Public Health. 2017;12:711–727. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2017.1316413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fekede B., G/Mariam A. Antenatal care services utilization and factors associated in Jimma Town (South West Ethiopia) Ethiop. Med. J. 2007;45:123–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gupta S., Yamada G., Mpembeni R., Frumence G., Callaghan-Koru J.A., Stevenson R., Brandes N., Baqui A.H. Factors Associated with Four or More Antenatal Care Visits and Its Decline among Pregnant Women in Tanzania between 1999 and 2010. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e101893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wablembo S.M., Doctor H.V. The influence of age cohort differentials on antenatal care attendance and supervised deliveries in Uganda. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2013;3:101. doi: 10.5430/jnep.v3n11p101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weldemariam S., Damte A., Endris K., Palcon M.C., Tesfay K., Berhe A., Araya T., Hagos H., Gebrehiwot H. Late antenatal care initiation: The case of public health centers in Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes. 2018;11:562. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3653-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terfasa T.G., Afework M.F., Berhe F.T. Antenatal Care Utilization and It’s Associated Factors in East Wollega Zone, Ethiopia. J. Pregnancy Child. Health. 2017;4:2–7. doi: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prusty R.K., Buoy S., Kumar P., Pradhan M.R. Factors associated with utilization of antenatal care services in Cambodia. J. Public Health. 2015;23:297–310. doi: 10.1007/s10389-015-0680-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Titaley C.R., Dibley M.J., Roberts C.L. Factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care services in Indonesia: Results of Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2002/2003 and 2007. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:485. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ali S.A., Dero A.A., Ali S.A., Ali G.B. Factors Affecting the Utilization of Antenatal Care among Pregnant Women: A Literature Review. J. Pregnancy Neonatal Med. 2018;2:41–45. [Google Scholar]