Abstract

Early career researchers (ECRs) are faced with a range of competing pressures in academia, making self-management key to building a successful career. The Organization for Human Brain Mapping undertook a group effort to gather helpful advice for ECRs in self-management.

Keywords: early career researchers, ECRs, self-management, career development, networking, mentoring

Introduction

Many PhD candidates dream of a research career. This constitutes a rewarding journey in the pursuit of new knowledge, often with meaningful contributions to society. It also represents a largely self-directed career with a high workload, but also with great flexibility in time management, similar to owning a business.

However, finding success in today’s scientific environment places competing demands on early career researchers (ECRs). We define ECRs as individuals pursuing academic research at the sub-tenure level, regardless of years of experience. At a time when reproducibility is of great concern in science, expectations for research skills in ECRs grow even higher (Poldrack, 2019): they are asked to avoid performing underpowered studies, to replicate their studies, and to maintain high standards of methodological rigor (Poldrack, 2019). While these developments improve the reliability of scientific findings, they may also negatively affect career-advancing metrics particularly important for ECRs, such as publication count and journal impact factor/prestige (Allen and Mehler, 2019). Trying to self-navigate under such pressure can be overwhelming, especially given extenuating circumstances that appear during a research career.

This article was created by the Organization for Human Brain Mapping (OHBM) Student and Postdoc Special Interest Group (SP-SIG) and collaborators at different career stages, from Masters students to Full Professors. Through our own experiences, we found that self-navigating in academia to be particularly daunting and counterintuitive. Access to career guidance varies greatly from institution to institution, and even lab to lab; thus, we have compiled information that we find both useful for self-navigating in academia, and broadly applicable. Although our recommendations are largely drawn from personal experience, relevant research studies are cited where possible. A summary of the introduced tools/strategies is given in Supplementary Material (Part 1).

Take charge of your own career development

Follow your curiosity and build expertise

Curiosity is the primary driver of scientific discovery. However, passion for research may only come with experience built over time; many successful scientists fall in love with what they do only after achieving some level of expertise in the field.

Develop clear long-term goals

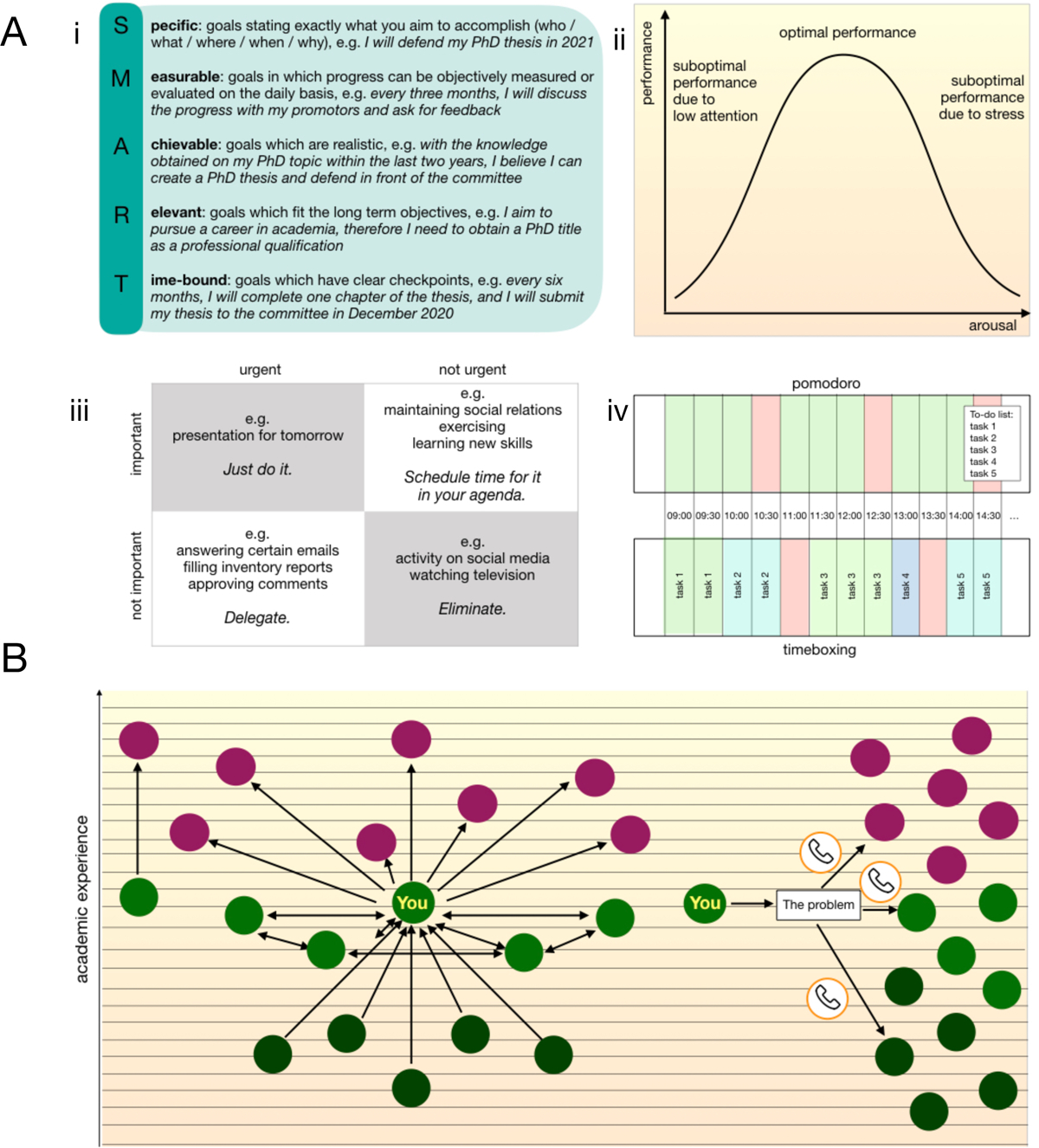

Citing Jim Rohn, “If you don’t design your own life plan, chances are you’ll fall into someone else’s plan.” Developing a clear vision and planning small steps towards the ultimate goals is necessary to steer your career. This will also help view small failures and setbacks as lessons and growth opportunities. Usually, only the clearly defined, measurable, and time-bound goals are achieved (Raia, 1965, Fig. 1A, i). Moreover, following Yerkes-Dodson law (Fig. 1A, ii), putting too much time/pressure on goals can lead to elevated stress, which can result in a cascade of errors, procrastination, and suboptimal performance.

Figure 1.

A Popular concepts for goal setting/time management. i: the S.M.A.R.T. approach for setting goals (Raia, 1965), with examples. ii: the Yerkes-Dodson law. There is an optimal level of arousal above which performance decreases due to high stress level. iii: the Eisenhower chart. The key to long term success is to manage important but not urgent tasks, iv: the pomodoro technique and timeboxing for planning work time. In the pomodoro technique, tasks are kept in lists and working time is pre-divided into periods of deep work (green) interleaved with breaks (red). In the timeboxing, every task is assigned with a precise time slot. B Models of mentoring. Left: the traditional, hierarchical view. Middle: modern, multilayered model. The mentee becomes the centre of their own mentoring network, with multiple mentors at different career stages (magenta), peer-coaching with other ECRs at a similar stage (light green), and more junior mentees (dark green). Right: “lifeline”/“advisory board” model: a network of mentors at different career stages serving as an advisory board.

Manage your time

Long-term goals can also help you say “no” by choosing tasks that provide delayed gratification over instant but insignificant rewards. Saying “no” is difficult but necessary. Most researchers fall into the trap of temporal discounting, where future time commitments matter less at the time of agreement. One strategy to overcome this issue is to imagine that the task is due tomorrow—would you still say “yes” on such a tight deadline?

According to Dwight D. Eisenhower, activities can be divided along two dimensions: important/not important and urgent/not urgent (Fig. 1A, iii). While important/urgent tasks are prioritized, proper management of important/non-urgent tasks (related to your long-term professional development, health, building bonds, etc.) are the real key to success. Furthermore, following Parkinson’s law, the more time you allocate to a given task, the more time the task will take. Practice delegating tasks that you do not need to do by yourself and consider implementing productivity strategies such as the pomodoro (free applications available, e.g., Time Out and Stretchly) or the timeboxing technique (Fig. 1A, iv).

Take care of yourself

Exercise

Exercising 2–3 times a week reduces the chances of depression, anger, stress and anxiety disorders. For example, walk or bike between home and work, or perform simple yoga stretches during the day. Group exercise sessions are also effective in controlling stress and improving mood.

Discover your optimal work style

When are you the most productive or most creative during the day? What is your preferred sleep schedule? What type of diet makes you feel the most energized? What makes you procrastinate? Knowing your optimal work style can help you achieve work-life balance.

Seek help

If your mood stays low for a prolonged period, you may benefit from therapy or counselling. While seeking professional help was often stigmatized in the past, it is increasingly being appreciated. Treat your mind as you would your body: take good care of your mental health, and go in for professional check-ups. Typically, academic institutions offer mental health services to their employees. Additionally, there are associations dedicated to this cause, e.g., Academic Mental Health Collective.

Join communities

Research suggests that among doctoral students and academics aged 18–34, isolation was the biggest contributor to reported mental health problems (Shaw, 2014). There are highly inclusive online associations open to ECRs that focus on career and personal development, such as the community of eLife Ambassadors.

Discern criticism

While (self)criticism is a part of the daily research routine, it is helpful to distinguish a critique of your work from criticism of you. Constructive criticism provides an opportunity for improvement. If criticism is destructive or personal, it is best not to react immediately, but to take a step back and understand the true motives underlying the criticism.

Clarify your rights on work-family balance

Either now or in the future, you will likely have caretaking responsibilities (children, partners, family members, etc.). In that case, ask a mentor or colleague you trust for support. Find out about your rights to statutory leave. Additionally, most employers have policies to grant additional leave and/or benefits above what is legally mandated: courses on work-family balance, a contract extension for caretakers, childcare support, and support groups for parents in research. You should also look for grants and fellowships that provide support for the continuation of your research during leave or upon return after a career break (check: ‘Scientist and parent’ series at eLife).

Make sure that you and your PI have similar expectations about work-life balance (e.g., consider options such as part-time employment) and have up-front discussions about your availability (or lack thereof) outside your normal work schedule.

Write a CV of failures

Success rates for publishing in high impact journals and obtaining grants can be 10% or lower, making academia very competitive. It is easy to get a false impression of chronic underachievement in such conditions.

In 2010, Dr. Melanie Stefan proposed writing a “CV of failures”, where only rejections and failures are documented (Stefan, 2010). Reading CVs of failures written by established researchers can be helpful, as it demonstrates that failure is an integral part of science and should not be taken personally. Documenting rejections can also be beneficial as an index of productivity and source of self-motivation: once you create a CV of failures, every action will add to either your official CV or the “shadow CV.”

Plan out your projects

You may find that your research project has bottlenecks that can delay its completion. You can increase the chances of successful completion by careful planning, and teamwork. Online scheduling tools, such as Slack or Trello, can help keep the team on track. If bottlenecks appear, you should ask yourself: “Can we decompose this problem into smaller and manageable chunks? Who is a useful contact to address each of these subproblems?” Communicate the bottlenecks clearly to your superiors as soon as they arrive. Be your own advocate—if you don’t ask for what you need, no one will know you need it.

Furthermore, consider developing side projects if your main project is burdened with bottlenecks outside your control. Think about your research activities as an investment portfolio: it should be diversified enough that the failure of one project will not tank your entire career. When you present your idea for risk diversification to your supervisors, treat it like a business pitch: professional, worthwhile and well-thought-out. Refer to Supplementary Material (Part 2) for comprehensive advice on minimizing risks in research projects.

Grow your network

Become the “go-to” person

Develop a core competence that will allow you to stand out in your research community, and develop a personal brand around it. Your niche can be anything: from proficiency in using a particular experimental tool to talent in community management. You can promote your skill by offering to help (e.g., through Twitter). Good news spreads fast; your colleagues will remember your willingness to help and spread the word whenever they hear about someone searching for this particular expertise.

Join Twitter

Twitter allows you to disseminate your work, get first-hand information (e.g., open calls for travel grants), have a voice in your community, and ask for opinions (Cheplygina et al., 2020). It is also common for online collaborative projects to begin on Twitter, engaging you in interesting side projects (Tennant et al., 2019). Funding opportunities can also be found on Twitter (e.g., @nihfunding, @nihgrants, @nsf, @ibrosecretariat). However, Twitter should be used responsibly, as it can become time-consuming and addictive.

Build online visibility

Aim to gradually increase your visibility online. Keep your LinkedIn, and Google Scholar profiles updated and linked to all your online outlets. You can also set up a personal website—even if you do not have an established research portfolio yet, you can post a blog or updates on your career activities (e.g., CV and/or failure CV). You can also search for yourself on Google and review the search results. If you see records you don’t want to be associated with, you can contact Google support to remove this information from search results, or contact the administrators of the website that features unwanted content.

Post Preprints

Consider posting preprints of your article and encouraging the research community to comment before submission to peer-reviewed journals. Articles preceded by a preprint are usually better cited than original submissions (Serghiou & Ioannidis, 2018), and the amount of online attention highly correlates with the impact factor of the eventual accepted journal. There are also certain downsides to preprints, e.g., not gaining enough online attention may discourage high-impact journal publication. However, posting preprints promotes your commitment to open science, which will be rewarded in the long run.

Give more presentations

It may be difficult and daunting to talk at a major conference at the beginning of your research career. Start by giving seminars at your own research institute and student conferences. You can also propose to be a guest online speaker in lab meetings to a junior professor you met at a conference. More talks bring more invitations, and practice makes perfect.

Join Hackathons

Hackathons are themed sprint-like events where participants conduct group research projects over a period of a few hours to a few days. Hackathons will allow you to develop: i) leadership skills, by converting and delegating parts of your project into Hackathon projects, or proposing small standalone projects; ii) research and networking skills, by joining other projects and building collaborations; iii) writing skills, by authoring project proposals and brief proceedings publications. You may find a list of exemplary science-themed Hackathons in Supplementary Material (Part 1).

Share your ideas with others

Blogs are a great tool to share your ideas and opinions. To start, you can consider writing guest posts for established blogs in your field. For example, the OHBM Student and Postdoc SIG leads a blog dedicated to ECRs, and is always open to featuring materials proposed by their readers.

You may also volunteer to review other researchers’ manuscripts and grants. For example, you can join ECR-dedicated grant reviewing programs, e.g., Early Career Reviewer Programme at NIH.

Supporting Open Science by sharing your work as an open-source resource, can also strengthen your research/networking skills. GitHub is a good place to start as it hosts code for many open-source tools and facilitates not only collaborations but also interactions with code developers. Sharing research tools and promoting them on Q&A sites such as NeuroStars can also increase networking opportunities and improve your work, as others may find issues or potential enhancements that were previously overlooked.

Mentoring is key

A common misunderstanding is that mentorship is just another aspect of day-to-day interactions with your supervisor (Fig. 1B, left). Creating a network of mentors can be more beneficial for providing diverse advice in different situations (Fig. 1B, middle). A “lifeline” model of mentoring (Fig. 1B, right), where you develop a mentoring environment of multiple helpful researchers whom you can call as a lifeline, is also recommended.

There are online resources that can assist mentees and mentors in making the mentoring process run smoothly. For example, the Early Faculty Online Training program at Stanford University offers information for mentees and mentors to develop a mentorship skill-set useful for researchers at many career stages. There is also an open initiative to increase the diversity in the biomedical research workforce from the National Research Mentoring Network (NRMN).

Join or create a peer coaching program

Peer mentoring is a particular form of mentorship, in which mentors and mentees at similar career stages cooperate in pairs. In this scheme, mentors and mentees usually self-manage their relationship. A recently popularized form of peer mentoring is a coaching group, which consists of researchers at similar career stages who support each other during a series of in person meetings, and are typically assisted by a trained facilitator. Peer coaching groups efficiently complement traditional mentoring. If there is no peer coaching group available at your institute, consider creating one with your fellow ECRs.

An alternative option is joining an online mentoring program. In such program, mentees are paired with mentors who may be geographically distant. For example, the OHBM offers an International Online Mentoring Program (Bielczyk & Veldsman et al., 2018) in which mentors are coupled with mentees on the basis of years of experience in active research and mutual expectations. Other examples include programs from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers where mentees can apply for a particular mentor; or 1000 Girls, 1000 Futures dedicated to women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM), which offers two hours of mentoring per month for a period of one year.

Conclusion

While many of the authors of this manuscript work in cognitive/computational neuroscience and psychology, we believe that the points discussed here apply for a broader ECR community. Although the demands of academia seem to be ever increasing, self-management of your career can increase your confidence and sense of control. There are also career options beyond academia, which may suit you better. In Supplementary Material (Part 3), we give additional advice to researchers considering a career switch to industry, and in Supplementary Material (Part 4), we list exemplary professions in which academic experience is an asset. For more information about post-PhD career tracks, you can reach out to (Bielczyk, 2019).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Allen CPG, and Mehler DM (2019). Open Science challenges, benefits and tips in early career and beyond. PLoS Biol. 7, e3000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielczyk* N, Veldsman* M, Ando A, Caldinelli C, Makary M, Nikolaidis A, Scelsi MA, Stefan M, OHBM Student and Postdoc Special Interest Group, Badhwar A (2018). Mentoring early career researchers: Lessons from the Organization for Human Brain Mapping International Mentoring Programme. Eur. J. Neurosci 49, 1069.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielczyk N (2019). What is out there for me? The landscape of post-PhD career tracks. Amazon Digital Services LLC. ISBN-10: 1675579660. [Google Scholar]

- Chekroud SR, Gueorguieva R, Zheutlin AB, Paulus M, Krumholz HM, Krystal JH, Chekroud AM (2018). Association between physical exercise and mental health in 1·2 million individuals in the USA between 2011 and 2015: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Psychiat. 5, 739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheplygina V (2018). How I fail. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20180817170504/http://veronikach.com/how-i-fail/

- Cheplygina V, Hermans F, Albers C, Bielczyk N, Smeets I (2020). Ten simple rules for getting started on Twitter as a scientist. PLoS Comp Biol. 16, e1007513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA (2019). The Costs of Reproducibility. Neuron 101, 11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raia AP (1965). Goal Setting and Self-Control: An Empirical Study. J. Manage. Stud 2, 34–53. [Google Scholar]

- Serghiou S, & Ioannidis JPA (2018). Altmetric Scores, Citations, and Publication of Studies Posted as Preprints. JAMA 319, 402–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C (2014, August 5). Overworked and isolated - work pressure fuels mental illness in academia. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2014/may/08/work-pressure-fuels-academic-mental-illness-guardian-study-health [Google Scholar]

- Stefan M (2010). A CV of failures. Nature 468, 467–467. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.