Abstract

Cobalt pyridine–diimine (PDI) complexes catalyze the reductive spirocyclopropanation of terminal 1,3-dienes. gem-Dichlorocycloalkanes serve as carbene precursors and Zn is used as a terminal electron source. The reaction is effective for a range of gem-dichloro partners including those containing sulfur and nitrogen heterocycles. An example of an intramolecular Rh-catalyzed [5 + 2]-cycloaddition of a vinyl spirocyclopropane is demonstrated, providing rapid access to a complex tricyclic framework. Overall, this catalyst system is capable of suppressing the kinetically facile 1,2-hydride shift, which has hampered the development of Simmons–Smith reactions using Zn carbenoids possessing β-hydrogen atoms.

Keywords: cyclopropanes, spiro compounds, cobalt, carbenes, carbenoids

Polycyclic C(sp3)-rich frameworks have recently attracted significant interest in medicinal chemistry.[1] Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions have provided a means to access large libraries of biologically active compounds. However, there is evidence to suggest that reliance on cross-coupling as a strategy for fragment-based drug discovery may be leading to higher rates of failure in clinical development due to the poor physical properties of flat aromatic systems (e.g., low solubility and high melting point).[2] One approach to addressing this problem is to prioritize lead compounds that contain higher fractions of sp3-hybridized carbons. In this vein, spirocyclopropanes[3] combine a unique three-dimensional architecture with conformational rigidity, thus representing high-value targets for the development of new synthetic methods.[4] Spirocyclopropanes may be prepared by the addition of a carbene equivalent to a methylenecycloalkane.[5],[6] An alternative disconnection that could be considered is the addition of a cyclic carbene to an alkene. Recently, Charette demonstrated the generation of sensitive diazocycloalkanes in flow reactors and their uncatalyzed addition to α,β-unsaturated esters.[7]

A conceptually straightforward route to spirocyclopropanes would be through a Simmons–Smith-like process using a metal carbenoid reagent derived from a 1,1-dihalocycloalkane. One impediment to realizing such a reaction is that there are no general methods available to prepare 1,1-diiodocycloalkanes.[8] 1,1-Dichloro analogs are more accessible but do not react directly with Zn or Et2Zn to form metal carbenoids. Secondly, Zn carbenoids are susceptible to kinetically facile 1,2-hydride shifts, leading to the formation of alkene side products.[9] Therefore, substituted Zn carbenoids containing β-hydrogen atoms are generally ineffective as cyclopropanating agents.[10]

We recently discovered that (PDI)CoBr2 complexes (PDI = pyridine–diimine) catalyze reductive dimethylcyclopropanation reactions of 1,3-dienes using 2,2-dichloropropane and Zn.[11] Notably, the catalyst is able to activate gem-dichloroalkane reagents and does not require the use of more reactive dibromo or diiodo precursors. Additionally, cyclopropanation proceeds in high yield with near-stoichiometric quantities of 2,2-dichloropropane, suggesting that the cobalt carbenoid intermediate generated in this reaction is resistant to undergoing 1,2-hydride shifts. With this precedent in hand, we sought to develop a catalytic reductive spirocyclopropanation reaction.

1,1-Dichlorocyclohexane (2) and 1,3-diene 1 were selected as model substrates for our initial optimization studies. 1,1-Dichlorocyclohexane (2) was prepared in a single step from cyclohexanone using WCl6 according to previously described procedures.[12] Using (2-t-BuPDI)CoBr2 complex 7, the optimal catalyst for the dimethylcyclopropanation reaction, product 3 was obtained in a modest yield of 38%. We reasoned that the more hindered carbenoid generated in the spirocyclopropanation reaction may require a less sterically encumbered catalyst active site. Indeed, significant improvements were observed by replacing the 2-t-Bu (7) substituent of the catalyst with a smaller 2-n-Pr (9) group. In our survey of PDI ligand derivatives (Table 1), this intermediate degree of hindrance was found to be optimal, with smaller or larger groups leading to decreases in spirocyclopropane yield. For all catalysts, the conversion of 2 is >27%, suggesting that low cyclopropanation yields are not exclusively due to slow C–Cl oxidative addition, but also to deleterious decomposition pathways of the carbenoid intermediate.

Table 1.

Catalyst Structure–Activity Relationship Studies.

|

Reaction conditions: 0.14 mmol of the 1,3-diene substrate, 1,1-dichlorocycloalkane (1.25 equiv), Zn (2.0 equiv), ZnBr2 (0.5 equiv), catalyst (10 mol%), room temperature, 24 h. Yields of 3 were determined by 1H NMR integration against 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

In the absence of Zn or any component of the (PDI)CoBr2 catalyst, no cyclopropanation was observed (Table 2, entries 2–4). Alternative reductants were examined (entries 5–10), and Mn was found to be equivalently competent. The soluble reagent Cp2Co provided no yield of cyclopropane (entry 9), and TDAE provided 3 in 19% yield (entry 10). Interestingly, ZnBr2 and ZnI2 afforded a significant beneficial effect on the yield of 3 despite the fact that ZnCl2 is formed as a stoichiometric byproduct of the reaction. ZnBr2/ZnI2 appears to accelerate the initial reduction of the (PDI)CoBr2 precatalyst as evidenced by a faster appearance of the violet color associated with the (PDI)CoBr oxidation state.

Table 2.

Reaction Optimization Studies and Control Experiments.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | variation from standard conditions | yield of 3 |

| 1 | – | 96% |

| 2 | no (2-n-PrPDI)CoBr2 | <1% |

| 3 | no CoBr2 | <1% |

| 4 | no PDI | <1% |

| 5 | Zn (nanopowder, 40–60 nm) | 87% |

| 6 | Mn instead of Zn | 96% |

| 7 | Mg instead of Zn | 42% |

| 8 | Al instead of Zn | 77% |

| 9 | Cp2Co instead of Zn | <1% |

| 10 | TDAE instead of Zn | 19% |

| 11 | no ZnBr2 | 60% |

| 12 | ZnCl2 instead of ZnBr2 | 68% |

| 13 | ZnI2 instead of ZnBr2 | >99% |

| 14 | Zn(OTf)2 instead of ZnBr2 | 3% |

Standard conditions: 0.14 mmol of the 1,3-diene substrate, 1,1-dichlorocycloalkane (1.25 equiv), Zn (2.0 equiv), ZnBr2 (0.5 equiv), catalyst 9 (10 mol%), room temperature, 24 h. Yields of 3 were determined by 1H NMR integration against 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

The substrate scope of the 1,3-diene spirocyclopropanation is summarized in Figure 2. The reaction is effective for a variety of terminal monosubstituted 1,3-dienes, including those possessing aliphatic, aromatic, and heteroaromatic groups. Notably, both electron-rich (products 14 and 15) and electron-deficient (products 20 and 21) dienes react with similar efficiency. This insensitivity to electronic effects stands in contrast with Zn carbenoid additions, which strongly favor electron-rich alkenes. Small internal substituents, such as Me, are also tolerated (product 19). (Z)-1,3-Dienes are cyclopropanated without isomerization of the internal double bond (product 13). Finally, this method enables the synthesis of spirocyclopropanes containing saturated nitrogen (products 25 and 28) and sulfur heterocycles (product 26).

Figure 2.

Substrate Scope Studies. Reaction conditions: 0.14 mmol of the 1,3-diene substrate, 1,1-dichlorocycloalkane (1.25 equiv), Zn (2.0 equiv), ZnBr2 (0.5 equiv), catalyst 9 (10 mol%), room temperature, 24 h. Isolated yields were determined following purification by column chromatography.

Simple monoalkenes such as 1-octene, styrene, and cyclohexene were unreactive under the standard spirocyclopropanation conditions (Figure 3a). However, moderately activated alkenes such as cyclooctene and indene proved to be viable substrates. Furthermore, (vinyl)Bpin reacted to form spirocyclic organoboron reagents (products 32–33) that could potentially serve as nucleophilic partners in cross-coupling reactions.[13] The relatively high reactivity of 1,3-dienes compared to monoalkenes can be leveraged to carry out a selective monocyclopropanation of a triene substrate (product 35, 71% yield). The resulting product was then subjected to Rh-catalyzed [5 + 2]-cycloaddition conditions to arrive at tricyclic product 36 in 47% yield.[14]

Figure 3.

(a) Spirocyclopropanation reactions of activated alkenes, including (vinyl)Bpin. (b) Selective monocyclopropanation of a triene and Rh-catalyzed [5 + 2]-cycloaddition.

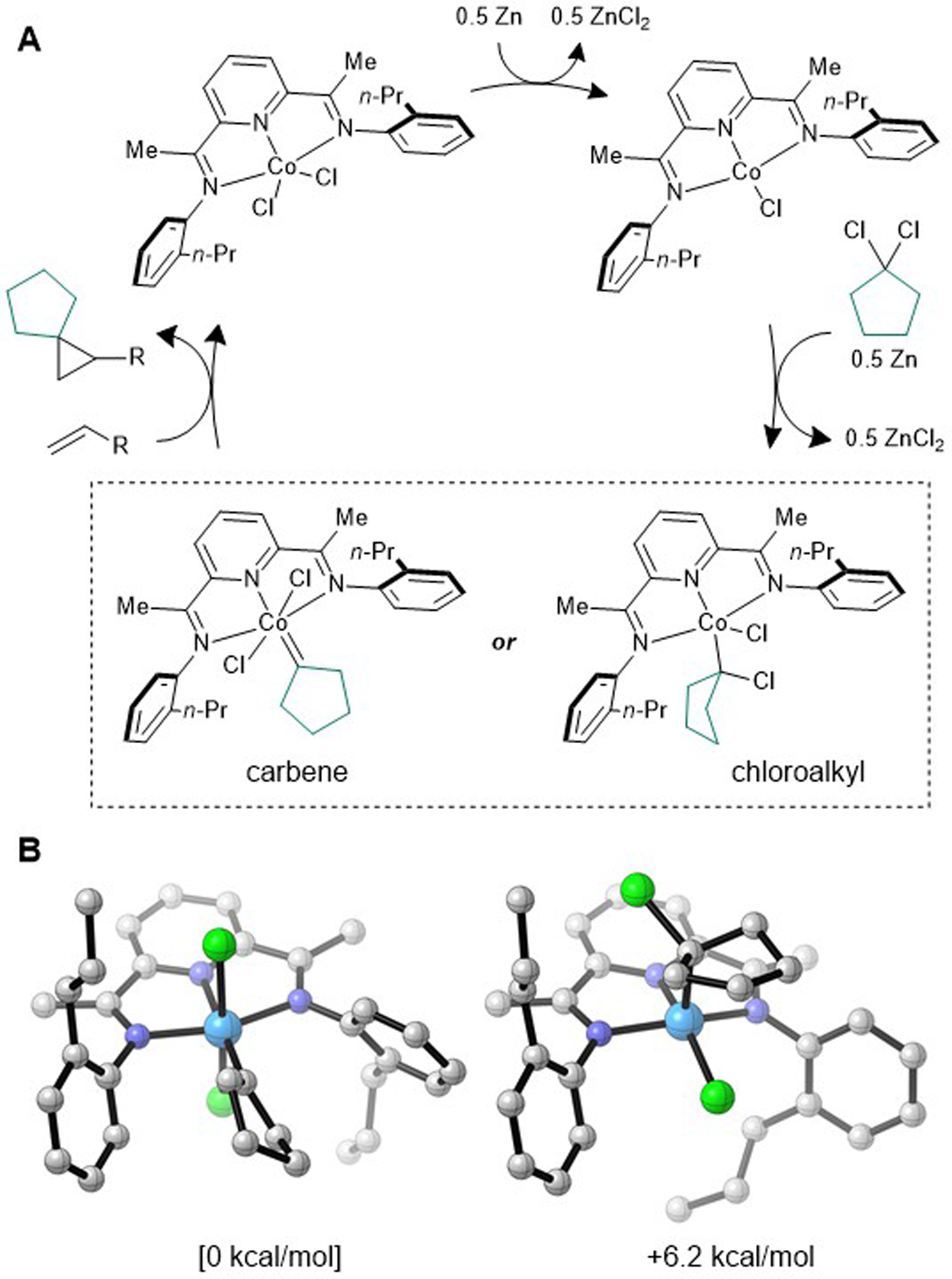

Mechanistic possibilities for the spirocyclopropanation are summarized in Figure 4a. Previous studies have indicated that Zn is capable of reducing (PDI)CoCl2 complexes to their corresponding (PDI)CoCl states.[15] Two-electron oxidative addition of the 1,1-dichlorocycloalkane reagent would then form a putative Co(CR2Cl)Cl2 species. However, because PDI ligands are not known to stabilize Co in the +3 oxidation state, we reasoned that if such a species were generated, it would be susceptible to rapid reduction by Zn to form a Co(II) carbenoid. Alternatively, a bimolecular oxidative addition may directly afford a Co(II) carbenoid along with an equivalent of (PDI)CoCl2. From here, a Simmons–Smith-like CR2 transfer through a butterfly transition state would generate the cyclopropane product.[16] Alternatively, Cl migration from C to Co could generate a Co=CR2 intermediate prior to carbene transfer.[17]

Figure 4.

(a) Mechanistic possibilities for the cobalt-catalyzed spirocyclopropanation reaction. (b) Optimized geometries for isomeric Co(C5H8)Cl2 and Co(C5H8Cl)Cl complexes (S = 1/2, BP86/6–311G(d,p)/SMD(THF)//BP86-D3BJ/6–311G(d,p) level of DFT). Calculated relative energies are shown in kcal/mol.

In order to examine these two limiting structures for the carbenoid intermediate in more detail, DFT modelling studies were performed (BP86/6–311G(d,p)/SMD(THF)//BP86-D3BJ/6–311G(d,p) level of theory). The (PDI)Co(CR2Cl)Cl complex was calculated to possess an S = 1/2 ground state and adopts a pseudo-square planar geometry with the CR2Cl ligand oriented axially. The (PDI)Co(CR2)Cl2 complex is lower in energy by 6.2 kcal/mol, and the carbene ligand prefers to be coplanar with the PDI ligand. The small energy difference between these two isomers does not allow either structure to be definitively ruled out as a potential catalytic intermediate.

In summary, cobalt catalysis enables the spirocyclopropanation of 1,3-dienes and activated alkenes using a 1,1-dichlorocycloalkane/Zn reagent combination. The carbenoid intermediate generated in this reaction is resistant to undergoing a 1,2-hydride shift, supressing the formation of olefin byproducts. Ongoing studies are aimed at examining the nature of the cobalt carbenoid intermediate generated in this reaction.

Experimental Section

General Procedure for the Catalytic Spirocyclopropanation of 1,3-Dienes

In an N2-filled glovebox, a 2-dram vial was charged with (2-n-PrPDI)CoBr2 9(8.6 mg, 0.014 mmol, 0.10 equiv), the 1,3-diene substrate (0.14 mmol, 1.0 equiv), Zn powder (18 mg, 0.28 mmol, 2.0 equiv), ZnBr2 (15 mg, 0.07 mmol, 0.50 equiv), THF (1.0 mL), and a magnetic stir bar. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for approximately 15 min, during which time a deep violet color developed. The 1,1-dichlorocycloalkane (0.175 mmol, 1.25 equiv) was added, and stirring was continued. After 24 h, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the crude residue was loaded onto a SiO2 column for purification.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Spirocyclopropanes in natural products and pharmaceutical compounds. Spirocyclopropanations of α,β unsaturated esters using diazocycloalkanes,[7] and catalytic reductive spirocyclopropanations using 1,1-dichlorocycloalkanes.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the NIH (R35 GM124791). C.U. is a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar.

References

- [1].Recent examples of spirocyclization reactions:; a) Saito F, Trapp N, Bode JW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 5544–5554; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Flodén NJ, Trowbridge A, Willcox D, Walton SM, Kim Y, Gaunt MJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 8426–8430; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhuo S, Zhu T, Zhou L, Mou C, Chai H, Lu Y, Pan L, Jin Z, Chi YR, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 1784–1788; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) King TA, Stewart HL, Mortensen KT, North AJP, Sore HF, Spring DR, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2019, 2019, 5219–5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lovering F, Bikker J, Humblet C, J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 6752–6756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Zheng Y, Tice CM, Singh SB, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2014, 24, 3673–3682; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Talele TT, J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 8712–8756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ladd CL, Sustac Roman D, Charette AB, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 1350–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Motherwell WB, Nutley CJ, Contemp. Org. Synth 1994, 1, 219–241; [Google Scholar]; b) Charette AB, Beauchemin A, Org. React 2001, 58, 1–415. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Recent examples of Simmons–Smith reactions of methylenecycloalkanes to prepare spirocyclopropanes:; a) Singh V, Vedantham P, Sahu PK, Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 8161–8169; [Google Scholar]; b) Riveiros R, Rumbo A, Sarandeses LA, Mouriño A, J. Org. Chem 2007, 72, 5477–5485; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Stappen I, Höfinghoff J, Friedl S, Pammer C, Wolschann P, Buchbauer G, Eur. J. Med. Chem 2008, 43, 1525–1529; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kumar AS, Thirupathi G, Reddy GS, Ramachary DB, Chem.-Eur. J 2019, 25, 1177–1183; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Yang J, Sun Q, Yoshikai N, ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 1973–1978. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Allouche EMD, Charette AB, Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 3802–3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Pross A, Sternhell S, Aust. J. Chem 1970, 23, 989–1003; [Google Scholar]; b) Barton DHR, Bashiardes G, Fourrey J-L, Tetrahedron 1988, 44, 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Neumann RC, Tetrahedron Lett. 1964, 5, 2541–2546; [Google Scholar]; b) Bull JA, Charette AB, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 1895–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shibli A, Varghese JP, Knochel P, Marek I, Synlett 2001, 2001, 0818–0820. [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Werth J, Uyeda C, Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 1604–1609; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Werth J, Uyeda C, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 13902–13906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jung ME, Wasserman JI, Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 7273–7275. [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Pietruszka J, Witt A, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 2000, 4293–4300; [Google Scholar]; b) Hussain MM, Hussain H. Li, N., Ureña M, Carroll PJ, Walsh PJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 6516–6524; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bassan EM, Baxter CA, Beutner GL, Emerson KM, Fleitz FJ, Johnson S, Keen S, Kim MM, Kuethe JT, Leonard WR, Mullens PR, Muzzio DJ, Roberge C, Yasuda N, Org. Process Res. Dev 2012, 16, 87–95; [Google Scholar]; d) Brondani PB, Dudek H, Reis JS, Fraaije MW, Andrade LH, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2012, 23, 703–708; [Google Scholar]; e) Harris MR, Li Q, Lian Y, Xiao J, Londregan AT, Org. Lett 2017, 19, 2450–2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wender PA, Husfeld CO, Langkopf E, Love JA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 1940–1941. [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Humphries MJ, Tellmann KP, Gibson VC, White AJP, Williams DJ, Organometallics 2005, 24, 2039–2050; [Google Scholar]; b) Raya B, Jing S, Balasanthiran V, RajanBabu TV, ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2275–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Nakamura M, Hirai A, Nakamura E, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 2341–2350; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nakamura E, Hirai A, Nakamura M, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 5844–5845. [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Bellow JA, Stoian SA, van Tol J, Ozarowski A, Lord RL, Groysman S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 5531–5534; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ikeno T, Iwakura I, Yamada T, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 15152–15153; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lu H, Dzik WI, Xu X, Wojtas L, de Bruin B, Zhang XP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 8518–8521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.