Abstract

Background

Although much of the public health effort to combat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has focused on disease control strategies in public settings, transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) within households remains an important problem. The nature and determinants of household transmission are poorly understood.

Methods

To address this gap, we gathered and analyzed data from 22 published and prepublished studies from 10 countries (20 291 household contacts) that were available through 2 September 2020. Our goal was to combine estimates of the SARS-CoV-2 household secondary attack rate (SAR) and to explore variation in estimates of the household SAR.

Results

The overall pooled random-effects estimate of the household SAR was 17.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.7–21.2%). In study-level, random-effects meta-regressions stratified by testing frequency (1 test, 2 tests, >2 tests), SAR estimates were 9.2% (95% CI, 6.7–12.3%), 17.5% (95% CI, 13.9–21.8%), and 21.3% (95% CI, 13.8–31.3%), respectively. Household SARs tended to be higher among older adult contacts and among contacts of symptomatic cases.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that SARs reported using a single follow-up test may be underestimated, and that testing household contacts of COVID-19 cases on multiple occasions may increase the yield for identifying secondary cases.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, household transmission, secondary attack, testing frequency

Nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as social distancing and mask wearing, have shown considerable promise in reducing transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). However, such measures may be difficult to implement within households, where transmission remains an important challenge for disease control.

Evidence regarding intrahousehold transmission dynamics is accumulating rapidly. Several primary studies and unpublished reviews have reported household secondary attack rates (SARs) for SARS-CoV-2 that converge in the 15–19% range [1, 2]. Many of the primary studies were conducted in China, where household structure (eg, a prevalence of multigenerational households) and roles (eg, allocation of responsibility for child or elder care) may affect generalizability to other domestic settings. To date, systematic reviews have not examined the sensitivity of SAR estimates to study design features, such as the frequency of follow-up testing. Consequently, there are substantial gaps in the understanding of SARS-CoV-2 transmission within households, hampering the development of prevention policies and protocols.

We reviewed and analyzed available studies of the household SARs for SARS-CoV-2. The analysis addressed aspects of measurement and study design that are likely to influence the reported estimates, including details of follow-up and testing, cases and contacts, and geographic settings. Our goal was to muster the best available evidence on infection risk among people living with someone with SARS-CoV-2, both to aid development of optimal disease control policies and improve the accuracy of epidemic forecasts. In addition, we sought to identify key gaps in existing evidence of the household SAR.

METHODS

Search Strategy And Selection Criteria

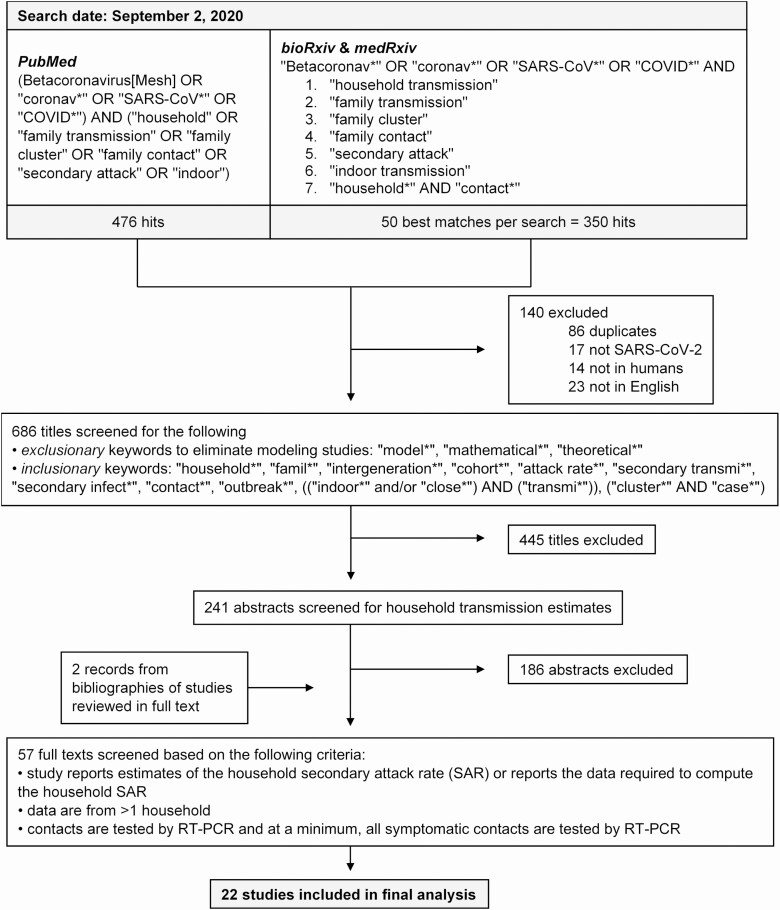

We searched PubMed, bioRxiv, and medRxiv on 2 September 2020 for published and prepublished studies reporting empirical estimates of household SARs for SARS-CoV-2. The search terms, which are reported in full in Figure 1, paired variants of the disease terminology (eg, “SARS-CoV*,” “COVID*”) with terms such as “household,” “secondary attack,” “family transmission,” “family contact,” and “indoor transmission.” We considered only English-language records posted on or after 1 January 2019.

Figure 1.

Study selection. Excluded records may have had more than 1 reason for exclusion, but only 1 reason was listed for each record. Records from bioRxiv and medRxiv that fell outside the 50 best matches were largely irrelevant (eg, not related to SARS-CoV-2 or examined the economic impact of the pandemic). Abbreviations: COVID, coronavirus disease; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SAR, secondary attack rate; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

To identify papers that were clearly out of scope, we developed a set of exclusionary and inclusionary keywords to screen out some papers on the basis of their titles alone (Figure 1). The exclusionary keywords were designed to eliminate modeling studies, and took precedence over inclusionary keywords. Eligible titles were reviewed at the abstract and full-text levels by 2 authors (H. F. F. and L. M.), and the bibliographies of studies reviewed in full text were screened for additional papers related to the household SAR.

Studies were included in the final sample if they met the following eligibility criteria: (1) they reported estimates of the household SAR or the data required to compute the household SAR; (2) they comprised data from more than 1 household; and (3) they tested—at a minimum—all symptomatic household contacts by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). We reviewed the subset of included studies to establish whether there was overlap in the study populations across multiple included studies. We employed more stringent eligibility criteria than existing reviews to mitigate sources of bias in our meta-analyses. For example, we excluded studies that did not test all symptomatic contacts, because they were likely to underestimate the household SAR. To minimize heterogeneity in the case definition, we considered only studies that used RT-PCR testing, rather than antibody testing.

The 2 reviewers (H. F. F. and L. M.) independently assessed the quality of each study using a modified 9-point Newcastle-Ottawa scale for observational studies [3]. Specifically, each study was evaluated on the basis of 3 criteria: selection of participants (4 points), comparability of studies (1 point), and ascertainment of the outcome of interest (3 points; Supplementary Table 1). Studies that scored 7 points or higher were classified as high quality, those that scored 4 to 6 points as moderate quality, and those with 3 or fewer points as low quality. The 2 reviewers discussed discrepancies in their scores and jointly reevaluated the relevant studies to reach consensus.

Study Definitions

We defined “household contacts” as people living in the same residence as the index case, and the “household SAR” as the percentage of all household contacts who were reported to have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR. Definitions of an “index case” came from the studies themselves, and were defined as either the first case to be confirmed in a household or the confirmed case with the earliest date of symptom onset. Such definitions run the risk of misclassifying asymptomatic index cases as secondary cases.

Data Analysis

All analyses were performed in R version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). We computed exact binomial confidence intervals for SAR estimates reported without uncertainty through the “Hmisc” package. We used random- and mixed-effects binomial-normal models (“metafor” package) to generate pooled estimates of the household SAR, and quantified the residual heterogeneity between studies using the I2 statistic. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. We did not account for household clustering, as the studies rarely reported the data needed for these calculations.

RESULTS

We found 826 papers from our multi-database search and 2 additional papers from the bibliographies of studies reviewed in full text, yielding 828 papers in total. Of these, 585 were excluded at the title review stage and 186 were excluded after abstract review (Figure 1). After conducting full-text reviews of the remaining 57 papers, we identified a final set of 22 papers that met our eligibility criteria. Of these, 20 papers were published and 2 were unpublished; 6 papers reported results of prospective studies and 16 reported retrospective studies.

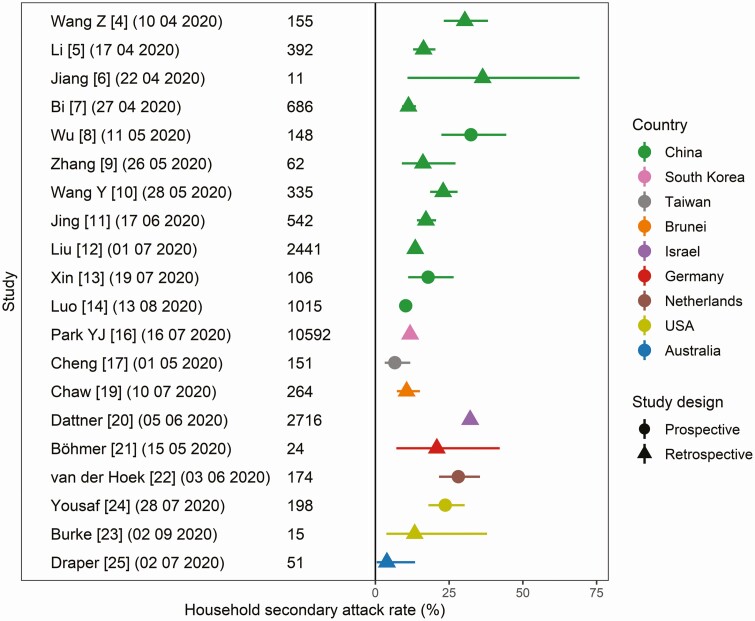

The number of household contacts evaluated per study ranged from 11 to 10 592 (Table 1; Figure 2). We classified 4 of the studies as high quality; 14 as moderate quality; and 4 as low quality (Supplementary Table 1). Half (11) of the studies analyzed households in China [4–14]; the rest analyzed households in South Korea [15, 16], Taiwan [17], Singapore [18], Brunei [19], Israel [20], Germany [21], the Netherlands [22], the United States [23, 24], and Australia [25]. The testing criteria were largely congruent across studies: 19 of the 22 studies tested all household contacts regardless of symptoms.

Table 1.

Household Secondary Attack Rates Stratified by Study Design

| Household Secondary Attack Rate, % (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By observation period | ||||||||

| Study | Enrollment Dates | Number of Index Cases | Number of Contacts | % Contacts Tested | Number of Tests Per Contact | <14 | 14 | >14 |

| Contacts tested regardless of symptoms | ||||||||

| Dattner et al [20] (Bnei Brak, Israel) | ~2020-03-17/2020-05-02 | 637 | 2716 | 100 | >2 | 32.1 (30.4–33.9) | … | … |

| Luo et al [14] (Guangzhou, China) | 2020-01-13/2020-03-06 | 391 | 1015 | Not provided | >2 | … | 10.3 (8.5–12.2) | … |

| Burke et al [23] (USA) | 2020-01-19/2020-01-30 | 9 | 15 | 100 | >2 | … | 13.3 (3.7–37.9) | … |

| Li et al [5] (Wuhan, China) | 2020-01-01/2020-02-13 | 105 | 392 | 100 | >2 | … | 16.3 (12.8–20.4) | … |

| Jiang et ala [6] (Shandong, China) | 2020-01-21/2020-01-29 | 4 | 11 | 100 | >2 | … | 36.4 (10.9–69.2) | … |

| Wu et al [8] (Zhuhai, China) | 2020-01-17/2020-02-29 | 35 | 148 | 100 | >2 | … | … | 32.4 (22.4–44.4) |

| Liu et al [12] (Guangdong, China) | 2020-01-10/2020-03-15 | 1158 | 2441 | 100 | 2 | 13.5 (12.2–14.9) | … | … |

| Bi et al [7] (Shenzhen, China) | 2020-01-14/2020-02-12 | 391 | 686 | 100 | 2 | … | 11.2 (9.1–13.8) | … |

| Zhang et alb [9] (Guangzhou, China) | 2020-01-28/2020-03-15 | 38 | 62 | 100 | 2 | … | 16.1 (9.0–27.2) | … |

| Jing et al [11] (Guangzhou, China) | 2020-01-07/2020-02-18 | 215 | 542 | 100 | 2 | … | 17.2 (14.1–20.6) | … |

| Xin et al [13] (Qingdao, China) | 2020-01-20/2020-03-27 | 31 | 106 | 100 | 2 | … | 17.9 (11.2–26.6) | … |

| Böhmer et al [21] (Bavaria, Germany) | 2020-01-27/2020-02-11 | Not provided | 24 | 100 | 2 | … | 20.8 (7.1–42.1) | … |

| Yousaf et al [24] (Milwaukee and Salt Lake City, USA) | 2020-03-22/2020-04-22 | Not provided | 198 | 100 | 2 | … | 23.7 (18.0–30.3) | … |

| van der Hoek et alc [22] (Netherlands) | 2020-03-23/2020-04-16 | 54 | 174 | 100 | 2 | … | … | 28.2 (21.6–35.5) |

| Cheng et al [17] (Taiwan) | 2020-01-15/2020-03-18 | 100 | 151 | 100 | 1 | … | 6.6 (3.2–11.8) | … |

| Chaw et al [19] (Brunei) | 2020-03-09/~2020-04-03 | 19 | 264 | 100 | 1 | … | 10.6 (7.3–15.1) | … |

| Park et al [16] (South Korea) | 2020-01-20/2020-03-27 | 5706 | 10 592 | 100 | Not provided | 11.8 (11.2–12.4) | … | … |

| Only symptomatic contacts tested | ||||||||

| Draper et al [25] (Northern Territory, Australia) | 2020-03-01/2020-04-30 | 28 | 51 | 18 | 1 | … | 3.9 (.5–13.5) | … |

| Wang Z et al [4] (Wuhan, China) | 2020-02-13/2020-02-14 | 85 | 155 | 67 | 1 | … | 30.3 (23.2–38.2) | … |

| Wang Y et ala [10] (Beijing, China) | 2020-02-28/2020-03-27 | 41 | 335 | Not provided | … | 23.0 (18.6–27.9) | … | |

Exact binomial confidence intervals were computed for estimates reported without uncertainty.

aSome households had more than 1 index case.

bSecondary attack rate among household contacts of presymptomatic cases.

cIncluded only households with children.

Figure 2.

Estimates of the household secondary attack rate, stratified by country and study design. Exact binomial confidence intervals were computed for estimates reported without uncertainty.

Of the China-based studies, 6 examined households in Guangdong province [7–9, 11, 12, 14]; the cohorts used in these studies did not overlap (personal communication, Guangdong Provincial Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). The households followed in the 2 studies from South Korea [15, 16] were not discrete: SY Park et al [15] used a subcohort of the cohort used in YJ Park et al [16]. Nevertheless, we chose to include the smaller study in our sample because it reported information that the larger study did not (namely, household SAR by index case symptoms), but we excluded it from analyses of the overall household SAR. The 2 studies from Wuhan, China [4, 5], recruited index cases from different hospitals and were considered distinct populations. The study from Singapore [18] focused on pediatric household contacts (≤16 years), and was included in our analysis only for the purpose of examining how the household SAR varied by age of contact.

In total, the 22 studies considered 20 291 household contacts, 3151 (15.5%) of whom tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Household SAR estimates ranged from 3.9% in the Northern Territory, Australia [25], to 36.4% in Shandong, China [6] (Figure 2). The overall pooled random-effects estimate of SAR was 17.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.7–21.2%), with significant heterogeneity (P < .0001; Supplementary Table 2).

Excluding the 2 unpublished studies had little effect on the pooled SAR estimate (16.8%; 95% CI, 13.4–20.8%; Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, study timing, operationalized as the enrollment start date, was not significantly related to SAR estimates (Supplementary Table 2).

Next, we computed SAR estimates by region to explore geographic differences. The SAR estimates were 18.1% (95% CI, 14.2–22.8%), 13.5% (95% CI, 7.2–23.9%), and 17.4% (95% CI, 9.7–29.4) for China, Asian countries outside of China, and countries outside of Asia, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). The pooled estimate tended to be higher among studies that defined the index case by symptom onset date (21.0%; 95% CI, 14.9–28.8%) than among studies that defined the index case as the first confirmed case (15.6%; 95% CI, 11.7–20.3%; Supplementary Table 2).

The amount of residual heterogeneity, as measured by the I2 statistic, decreased from 96.7% to 91.2% after accounting for follow-up duration and testing frequency, suggesting these study features were important determinants of the household SAR estimates (Supplementary Table 2; Table 1). Between-study variation could not be explained by differences in study quality (I2 was 96.5% when study quality was included as a moderator variable; Supplementary Table 2).

Estimates of the household SAR were lower, on average, in studies with less frequent testing of contacts. Random-effects regressions stratified by frequency of follow-up testing revealed that studies with >2 follow-up tests of contacts reported an average household SAR of 21.3% (95% CI, 13.8–31.3%), whereas those with 2 follow-up tests averaged 17.5% (95% CI, 13.9–21.8%) and those with a single follow-up test averaged 9.2% (95% CI, 6.7–12.3%; Supplementary Table 2).

The household SARs were higher among adults and older adults than among children, and higher among female contacts and contacts of symptomatic cases (Tables 2–5; Supplementary Figure). SARs were also elevated among spouses or significant others of index cases relative to nonspouse household members (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 2.

Household Secondary Attack Rates by Index Case Symptoms

| Household Secondary Attack Rate, % (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By index case symptoms | ||||

| Study | Sample Size | Symptomatic | Presymptomatic | Asymptomatic |

| Chaw et al [19] (Brunei) | 264 | 14.4 (8.8–19.9) | 6.1 (.3–11.8) | 4.4 (0–10.5) |

| Park et al [15] (Seoul, South Korea) | 225 | 16.2 (11.6–22.0) | 0 (0–28.5) | 0 (0–60.2) |

| Zhang et al [9] (Guangzhou, China) | 62 | … | 16.1 (9.0–27.2) | … |

Exact binomial confidence intervals were computed for estimates reported without uncertainty.

Table 3.

Household Secondary Attack Rates by Index Case Age Group

| Household Secondary Attack Rate, % (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By index case age group | ||||

| Study | Sample Size | Children | Adults | Older adults |

| Park et al [16] (South Korea) | 10 592 | 16.0 (11.9–20.7)a | 10.5 (9.9–11.2) | 16.8 (15.1–18.6)b |

| Xin et al [13] (Qingdao, China) | 106 | 12.5 (5.9–22.4) | 29.4 (15.1–47.5)c | |

Exact binomial confidence intervals were computed for estimates reported without uncertainty.

a0–19 years.

b≥60 years.

c≥55 years.

Table 4.

Household Secondary Attack Rates by Household Contact Age Group

| Household Secondary Attack Rate, % (95% Confidence Interval) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By household contact age group | |||||

| Study | Sample Size | Rising Trend With Age? Y/N | Children | Adults | Older adults |

| Dattner et al [20] (Bnei Brak, Israel) | 2716 | Y | 25.4 (23.3–27.5)a | 43.9 (40.4–47.4) | 45.7 (38.0–53.6)b |

| Bi et al [7] (Shenzhen, China) | 628 | Y | 9.6 (5.6–15.2)a | 11.4 (8.2–15.4) | 17.7 (11.6–25.4)b |

| Jing et al [11] (Guangzhou, China) | 537 | Y | 6.4 (2.8–12.2)a | 18.5 (14.4–23.2) | 28.0 (19.1–38.2)b |

| Li et al [5] (Wuhan, China) | 392 | N | 4.0 (1.1–9.9)c | 22.4 (17.2–28.2) | 12.7 (5.3–24.5)d |

| Yung et al [18] (Singapore) | 213 | … | 6.1 (3.3–10.2)e | … | … |

| Yousaf et al [24] (Milwaukee and Salt Lake City, USA) | 198 | Y | 20.3 (11.6–31.7)c | 25.4 (17.9–34.3) | 37.5 (8.5–75.5)f |

| van der Hoek et al [22] (Netherlands) | 174 | Y | 24.3 (16.5–33.5)c | 27.8 (14.2–45.2) | 41.9 (24.6–60.9)g |

| Wu et al [8] (Zhuhai, China) | 143 | Y | 16.1 (5.5–33.7)h | 37.0 (24.2–52) | 41.9 (23.5–62.9)d |

| Xin et al [13] (Qingdao, China) | 106 | N | 20.5 (12.4–30.8) | 8.7 (1.1–28.0)i | |

Exact binomial confidence intervals were computed for estimates reported without uncertainty. Abbreviation: Y/N, yes/no.

a0–19 years.

b≥60 years.

c0–17 years.

d>60 years.

e0–16 years.

f≥65 years.

g>45 years.

h0–18 years.

i≥55 years.

Table 5.

Household Secondary Attack Rates by Household Contact Sex

| Household Secondary Attack Rate, % (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| By household contact sex | |||

| Study | Sample Size | Female | Male |

| Jing et al [11] (Guangzhou, China) | 538 | 18.9 (14.5–24.0) | 15.5 (11.3–20.5) |

| Li et al [5] (Wuhan, China) | 392 | 17.1 (11.9–23.4) | 15.6 (11.0–21.3) |

| Yung et al [18] (Singapore) | 212 | 5.0 (1.6–11.2)a | 7.1 (3.1–13.6)a |

| Yousaf et al [24] (Milwaukee and Salt Lake City, USA) | 198 | 29.3 (20.6–39.3) | 18.8 (11.5–28.0) |

| Wu et al [8] (Zhuhai, China) | 143 | 36.3 (24.6–49.7) | 30.2 (18.5–45.1) |

| Xin et al [13] (Qingdao, China) | 106 | 21.6 (11.3–35.3) | 14.5 (6.5–26.7) |

Exact binomial confidence intervals were computed for estimates reported without uncertainty.

a0–16 years.

There were 2 studies that reported the household SAR by age of the index case (Table 3). In the study from Qingdao, China [13], the household SAR was higher when index cases were 55 years or older than when cases were younger than 55 years (Table 3). In South Korea [16], the household SAR was highest for index cases aged 10–19 years (18.6%; 95% CI, 14.0–24.0%) and lowest for those younger than 9 (5.3%; 95% CI, 1.3–13.7%); by comparison, the SAR estimates for adult age groups ranged from 7.0 to 18.0% (Supplementary Table 3).

There are a number of additional factors that could have influenced household SAR estimates, including mask use and index case severity. A small subset of the studies considered these factors, and their findings are summarized in Supplementary Table 5.

DISCUSSION

While much of the public health effort in controlling SARS-CoV-2 has appropriately focused on preventing community transmission, people who reside with infected individuals are an important group; they are at substantial risk of infection due to prolonged, close contact. Available estimates of the SAR within households vary widely, and the determinants of transmission risk, including age of index cases and contacts, are only beginning to be understood. In this review of studies to date, we calculated a household SAR of 17.1% (95% CI, 13.7–21.2%). Importantly, we observed considerable heterogeneity in household SAR estimates, and there appeared to be systematic variation according to identifiable aspects of study design.

In particular, studies that tested contacts more frequently tended to generate larger SARs. This suggests that studies with less intensive testing may have missed cases and underestimated the household SAR. Other aspects of study design and setting are likely to contribute to variation in the observed estimates; they include approaches to case selection, how quickly symptomatic index and secondary cases were detected, the timing of testing, and the phase of the epidemic.

Although only a minority of studies reported household SARs by contact age, the available evidence suggests that the estimates are sensitive to this variable. Most of these studies found higher SARs among adults than children. Whether this is due to differential susceptibility to infection or differential exposure to the index case is not yet clear for SARS-CoV-2, but the higher SARs in children for other respiratory viruses (such as 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza [26, 27]) suggests that differential exposure is unlikely to fully explain these discrepancies. Other hypotheses for lower household SARs among children (and asymptomatic contacts) include lower viral loads, leading to low sensitivity of RT-PCR tests, or a lower probability of testing.

Our review identified only a few studies that examined the relationships between household SAR and the age and symptomatic status of the index case. While results suggest that index cases who are young children (between 0 and 9 years) and index cases who are asymptomatic may have lower household SARs, further studies are critically needed to clarify the effects of age and symptoms of cases on household transmission risks.

Other characteristics of households and household members—including some that were not observed or reported in existing studies—are likely to affect the household SAR, and explain some of the substantial heterogeneity in reported estimates. The number of cohabitants and the density of living conditions (eg, number of household members per room) are almost certainly influential. Relatedly, there are likely influences based on isolation and prevention practices within the household: both what is feasible and the extent to which feasible options are pursued. For example, the study based in Bnei Brak, Israel [20], followed a cohort of households with relatively large numbers of cohabitants living in a close-knit community; these factors plausibly contributed to the study’s reported household SAR of 32.1% (95% CI, 30.4–33.9%), which was at the high end of all estimates in our sample. Furthermore, mask use within households is likely to be protective, but only 1 study [8] stratified the household SAR by index case mask use. Additional studies are required to elucidate the effects of masks on household transmission. Lastly, the index case severity and the timing of testing are likely determinants of transmission potential. Few studies, however, considered these factors in the context of household SAR.

The main limitations of our analysis spring from limitations in available data and studies, though much has been accomplished in understanding a pandemic that has raged for less than a year. In particular, caution must be taken in generalizing summary statistics, like household SARs, across countries and regions. Household size and composition, contact patterns, and testing and isolation practices all vary substantially geographically. None of the included studies come from South Asia, Latin America, or Africa, although these places account for a substantial proportion of the global caseload [28]. This review suggests there is a critical need for studies in these regions to investigate whether there are setting-specific differences that influence the household SAR.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been devastating, and many countries are working actively to formulate effective strategies for containment. While preventing spread in congregate public settings is a critical first step, a full-fledged strategy for reducing transmission must also involve interventions to prevent transmission within households [29, 30]. Such interventions have begun to take place in some settings and may include early case detection, isolation of cases, systematic investigation and quarantine of exposed household contacts, and the development and use of effective postexposure chemoprophylaxis among exposed household members [31]. Design and implementation of these strategies—including prioritization of cases and contacts who pose and face the greatest risk—should be informed by a better understanding of the extent, nature, and determinants of transmission in households.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Study group. The Stanford-CIDE Coronavirus Simulation Model (SC-COSMO) modeling group consists of authors H. F. F., F. A.-E., J. A. S., D. M. S., J. R. A., and J. D. G.-F., and of Elizabeth T. Chin, Anneke L. Claypool, Mariana Fernandez, Valeria Gracia, Andrea Luviano, Regina Isabel Medina Rosales, Marissa Reitsma, and Theresa Ryckman.

Disclaimer. The funders did not contribute to the design, conduct, or analysis of this study, or to the manuscript development, writing, or review. The corresponding author had access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported in part by a contract with the California Department of Technology (agreement number 19-13050) and by the Stanford School of Medicine Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Emergency Response Fund, established with generous gifts from donors. Additionally, this work was supported by the National Institute On Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (award number R37DA015612).

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Contributor Information

Stanford-CIDE Coronavirus Simulation Model (SC-COSMO) Modeling Group:

Elizabeth T Chin, Anneke L Claypool, Mariana Fernandez, Valeria Gracia, Andrea Luviano, Regina Isabel Medina Rosales, Marissa Reitsma, and Theresa Ryckman

References

- 1. Koh WC, Naing L, Rosledzana MA, et al. What do we know about SARS-CoV-2 transmission? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the secondary attack rate, serial interval, and asymptomatic infection. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0240205. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.21.20108746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Madewell ZJ, Yang Y, Longini IM Jr, Elizabeth HM, Dean NE. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis of secondary attack rate. MedRxiv [Preprint]. July 31, 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 6]. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.29.20164590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 14 August 2020.

- 4. Wang Z, Ma W, Zheng X, Wu G, Zhang R. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2. J Infect 2020; 81:172-82. doi:S0163-4453(20)30169-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li W, Zhang B, Lu J, et al. Characteristics of household transmission of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71(8):1943–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiang XL, Zhang XL, Zhao XN, et al. Transmission potential of asymptomatic and paucisymptomatic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections: a 3-family cluster study in China. J Infect Dis 2020; 221:1948–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20:911–19. doi:S1473-3099(20)30287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu J, Huang Y, Tu C, et al. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2, Zhuhai, China, 2020. Clin Infect Dis [Preprint]. May 11, 2020 [Cited 2020 Sep 6]. 2020; 71(16):2099–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang W, Cheng W, Luo L, et al. Secondary transmission of coronavirus disease from presymptomatic persons, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26:1924–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Y, Tian H, Zhang L, et al. Reduction of secondary transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in households by face mask use, disinfection and social distancing: a cohort study in Beijing, China. BMJ Glob Health 2020; 5:e002794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jing QL, Liu MJ, Zhang ZB, et al. Household secondary attack rate of COVID-19 and associated determinants in Guangzhou, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis [Preprint]. 2020; 20:1141–50. doi:S1473-3099(20)30471-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu T, Liang W, Zhong H, et al. Risk factors associated with COVID-19 infection: a retrospective cohort study based on contacts tracing. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020; 9:1546–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xin H, Jiang F, Xue A, et al. Risk factors associated with occurrence of COVID-19 among household persons exposed to patients with confirmed COVID-19 in Qingdao Municipal, China. Transbound Emerg Dis [Preprint] July 20, 2020 [Cited 2020 Sep 6]. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luo L, Liu D, Liao XL, et al. Contact settings and risk for transmission in 3410 close contacts of patients with COVID-19 in Guangzhou, China: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med [Preprint] August 13, 2020 [Cited 2020 Sep 6]. Available from: 10.7326/M20-2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park SY, Kim YM, Yi S, et al. Coronavirus disease outbreak in call center, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26:1666–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park YJ, Choe YJ, Park O, et al. ; Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) National Emergency Response Center, Epidemiology and Case Management Team . Contact tracing during coronavirus disease outbreak, South Korea, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26:2465–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cheng HY, Jian SW, Liu DP, Ng TC, Huang WT, Lin HH. Contact tracing assessment of COVID-19 transmission dynamics in Taiwan and risk at different exposure periods before and after symptom onset. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180:1156–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yung CF, Kam KQ, Chong CY, et al. Household transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from adults to children. J Pediatr [Preprint]. 2020; 225:249–51. doi:S0022-3476(20)30852-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chaw L, Koh W, Jamaludin S, Naing L, Fathi M, Wong J. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in different settings, among cases and close contacts from the Tablighi cluster in Brunei Darussalam. MedRxiv [Preprint]. July 10, 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 6]. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.04.20090043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dattner I, Goldberg Y, Katriel G, et al. The role of children in the spread of COVID-19: using household data from Bnei Brak, Israel, to estimate the relative susceptibility and infectivity of children. MedRxiv [Preprint]. June 5, 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 6]. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.03.20121145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Böhmer MM, Buchholz U, Corman VM, et al. Investigation of a COVID-19 outbreak in Germany resulting from a single travel-associated primary case: a case series. Lancet Infect Dis [Preprint]. 2020; 20:920–8. doi:S1473-3099(20)30314–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van der Hoek W, Backer JA, Bodewes R, et al. De rol van kinderen in de transmissie van SARS-CoV-2. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2020; 164:D5140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burke RM, Balter S, Barnes E, et al. Enhanced contact investigations for nine early travel-related cases of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States. PLOS One 2020; 15:e0238342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yousaf AR, Duca LM, Chu V, et al. A prospective cohort study in non-hospitalized household contacts with SARS-CoV-2 infection: symptom profiles and symptom change over time. Clin Infect Dis [Preprint]. July 28, 2020 [Cited Sep 6] 2020; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Draper AD, Dempsey KE, Boyd RH, et al. The first 2 months of COVID-19 contact tracing in the Northern Territory of Australia, March–April 2020. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2020; 44. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2020.44.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cauchemez S, Donnelly CA, Reed C, et al. Household transmission of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus in the United States. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:2619–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tsang TK, Lau LLH, Cauchemez S, Cowling BJ. Household transmission of influenza virus. Trends Microbiol 2016; 24:123–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation report – 200. Available at http://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200807-covid-19-sitrep-200.pdf?sfvrsn=2799bc0f_2. Accessed 14 August 2020.

- 29. Peak CM, Kahn R, Grad YH, et al. Individual quarantine versus active monitoring of contacts for the mitigation of COVID-19: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20:1025–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baker MG, Wilson N, Anglemyer A. Successful elimination of COVID-19 transmission in New Zealand. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:e56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ikematsu H, Hayden FG, Kawaguchi K, et al. Baloxavir marboxil for prophylaxis against influenza in household contacts. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:309–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.