Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (officially declared on the March 11, 2020), and the resulting measures, are impacting daily life and medical management of breast cancer patients and survivors. We evaluated to what extent these changes have affected quality of life, physical, and psychosocial well-being of patients previously or currently being treated for breast cancer.

Methods

This study was conducted within a prospective, multicenter cohort of breast cancer patients and survivors (Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaLuAtion). Shortly after the implementation of COVID-19 measures, an extra survey was sent to 1595 participants, including the validated European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) core (C30) and breast cancer-

specific (BR23) Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30/BR23) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) were compared with the most recent PROs collected within UMBRELLA pre–COVID-19. The impact of COVID-19 on PROs was assessed using mixed model analysis, adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

1051 patients and survivors (65.9%) completed the survey; 31.1% (n = 327) reported a higher threshold to contact their general practitioner amid the COVID-19 pandemic. A statistically significant deterioration in emotional functioning was observed (mean = 82.6 [SD = 18.7] to 77.9 [SD = 17.3]; P < .001), and 505 (48.0%, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 45.0% to 51.1%) patients and survivors reported moderate to severe loneliness. Small improvements were observed in quality of life and physical, social, and role functioning. In the subgroup of 51 patients under active treatment, social functioning strongly deteriorated (77.3 [95% CI = 69.4 to 85.2] to 61.3 [95% CI = 52.6 to 70.1]; P = .002).

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, breast cancer patients and survivors were less likely to contact physicians and experienced a deterioration in their emotional functioning. Patients undergoing active treatment reported a substantial drop in social functioning. One in 2 reported loneliness that was moderate or severe. Online interventions supporting mental health and social interaction are needed during times of social distancing and lockdowns.

With the outbreak of the novel and rapidly spreading coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), many extraordinary emergency measures have been taken to prevent and control spread of the virus (1-3). National restrictions varied from total lockdown to targeted quarantine and social distancing (4-6). In the Netherlands, specific governmental measures included stay-at-home orders when experiencing mild symptoms, social distancing (1.5 meter), closure of schools and public places, and canceling all public events. Despite drastic efforts, the World Health Organization officially declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (7).

As the COVID-19 pandemic has put healthcare systems under unprecedented stress, urgent rearrangements of non–COVID-19–related health care has been of vital importance (6,8-11). To prioritize hospital capacity for critically ill COVID-19 patients, elective care was suspended as much as possible, and only emergency care and semi-urgent oncological procedures were continued (6,12-14). For breast cancer, surgical procedures were postponed when possible, various types of treatment protocols (chemo- and radiotherapy) were adapted, and follow-up appointments canceled, postponed, or transformed into (video)calls (9,15). Also, paramedical care and aftercare such as medical rehabilitation and psychological support was scaled down to a minimum, and national breast cancer screening programs were temporarily halted (12,16).

Delays and changes in breast cancer diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up protocols due to COVID-19 may potentially induce concerns about recurrence or survival (16). This, in combination with concerns about the new viral threat in general, could impair patients’ and survivors’ mental and emotional well-being. Previous literature showed that, in general, women with a history of breast cancer have an increased risk of anxiety and depression, and that social support is crucial for supporting quality of life (QoL) and mental health in patients previously or currently being treated for breast cancer (17-19). Measures of social distancing or lockdown may interfere with networks of support and have a negative impact on mental health and emotional functioning. However, to date, no previous studies have used patient-reported outcome scores (PROs) of breast cancer patients and survivors in the context of COVID-19.

The purpose of this study was to measure the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient-reported QoL, physical, and psychosocial functioning in a prospective cohort of patients previously or currently being treated for breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

The present study was conducted within the ongoing prospective multicenter Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaLuAtion (UMBRELLA) (20,21). Since 2013, the UMBRELLA cohort included patients aged 18 years or older, who were routinely referred by 6 hospitals in the Utrecht region to the Department of Radiation Oncology of the University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands. Inclusion criteria were histologically proven invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ and the ability to understand the Dutch language (written and spoken). Prior to the first appointment with the radiation oncologist, breast cancer patients were routinely invited to participate in the UMBRELLA cohort. Participants provided informed consent for longitudinal collection of clinical data and PROs through paper or online questionnaires at regular intervals during and after treatment (before the start of radiation therapy [baseline], after 3 and 6 months, and each 6 months up to 10 years thereafter) (20). Clinical data, including patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics, were provided by the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NKR).

Details on pre- and during COVID-19 treatment protocols are presented in the Supplementary Methods (available online). The UMBRELLA study adheres to the Dutch law on Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (WMO) and the Declaration of Helsinki (version 2013). The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht (NL52651.041.15, Medical Ethics Committee 15/165) and is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02839863).

Data Collection

On April 7, 2020, shortly after the introduction of the Dutch COVID-19 measures (March 12, 2020), an additional COVID-19–specific online survey was sent to all active UMBRELLA cohort participants who were enrolled between October 2013 and April 2020 with a known e-mail address. Diseased UMBRELLA participants were excluded, as well as those who were not responding to standard UMBRELLA questionnaires and those electing paper questionnaires. One reminder was sent on April 15, 2020. The survey included 2 standard UMBRELLA PRO questionnaires (European Organization for Research and Treatment [EORTC] core [C30] and breast cancer-specific [BR23] Quality of Life Questionnaire [QLQ] and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]) and 2 additional questionnaires (De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale and a COVID-19–specific questionnaire).

The cancer-specific Quality of Life Core Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) of the EORTC was used to assess global health-related QoL; physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social functioning; dyspnea; insomnia; and financial difficulties (22). Patients’ and survivors’ future perspective was evaluated with the breast cancer–specific module (QLQ-BR23). For each subscale, a summary score was calculated according to the EORTC manual (23).

The HADS was used to assess symptoms of anxiety and depression (24). Patients and survivors with scores above 7 are at risk of having anxiety or depressive disorders (25).

Overall, emotional and social loneliness were assessed using the 6-item De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale (26). Scores between 2 and 4 represent moderate loneliness, and a score above 4 represents severe loneliness (27). Scores above 2 on each of the 3-item subscales for emotional and social loneliness indicate emotional and social loneliness, respectively (27).

Additional questions were developed to assess presence of (symptoms resembling) COVID-19 and the impact of COVID-19 on healthcare consumption and expectations.

PROs during COVID-19 were compared with the most recent pre–COVID-19 PROs as obtained within UMBRELLA. Patients and survivors were excluded from comparative analyses when their most recent questionnaire was completed more than 2 years before the first confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis in the Netherlands (February 27, 2020).

Clinical data was obtained from electronic patient records and from the UMBRELLA dataset as retrieved from NKR and included age at cohort enrollment, body mass index, smoking status, self-reported highest educational level, surgical treatment, axillary treatment, (neo-)adjuvant radiation therapy and systemic treatment, currently receiving active treatment, and pathological T- and N-stage (American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] 7th edition).

Statistical Analysis

Frequencies, proportions, and means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), as appropriate, were used to describe patient and clinical characteristics, COVID-19–related questions, and PROs.

To measure the impact of COVID-19 on PROs using complete case analyses (ie, only including patients and survivors who completely filled out PROs pre–COVID-19 and during COVID-19), most recent reported EORTC QLQ-C30/BR23 and HADS scores from prior to COVID-19 were compared with the PROs during COVID-19. Crude mean EORTC scores were compared with the paired samples t test and crude median HADS scores with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

To estimate whether the impact of COVID-19 on clinically relevant PROs varied with time since (active) treatment, patients and survivors were categorized into 4 groups (ie, active treatment; nonactive treatment and enrolled in UMBRELLA less than 24 months before the survey; nonactive treatment and enrolled 24-60 months before the survey; and nonactive treatment and enrolled more than 60 months before the survey). A linear mixed effect model for repeated measurements was used to measure the impact of COVID-19 on PROs. The model included a patient-specific random intercept, a random linear time effect to allow a patient-specific slope, and an interaction between months since diagnosis and time point. Two time points were included in the model: PROs prior to COVID-19 (ie, measurement of last follow-up pre–COVID-19) and PROs during COVID-19. A random slope was chosen to account for a difference in time effect for each patient. To correct for potential confounders, age (linear) was included as fixed variable in the model in the nonactively treated group. In the actively treated group, further adjustment was performed for type of radiotherapy and type of surgery. Only fixed effects without missing cases were included in the model. Changes in PROs due to COVID-19 were reported as mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

All reported P values were 2-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences software, version 25 (SPSS; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

Study Population

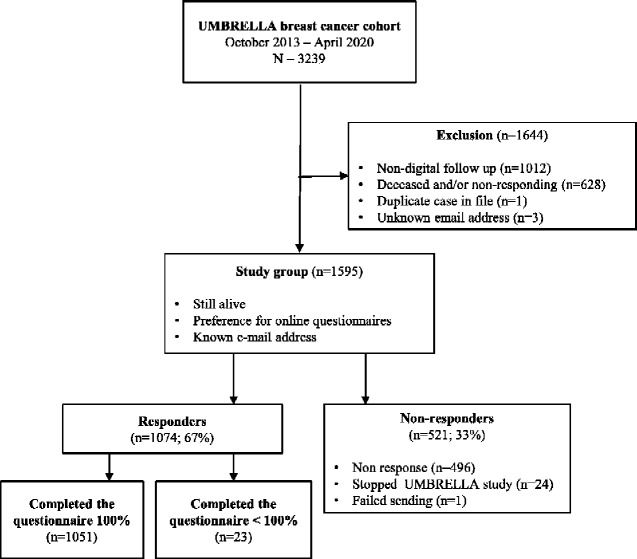

Between October 2013 and April 2020, 3239 patients previously or currently being treated for breast cancer were enrolled in UMBRELLA (Figure 1). Of all UMBRELLA participants, 1595 met the inclusion criteria for the present study and were sent the extra COVID-19 survey, of whom 1051 patients and survivors (65.9%) responded. Mean age was 56 (SD = 9.8) years, and median time since diagnosis was 24 (IQR = 6-42) months (Table 1). Most patients and survivors (55.7%) were treated for a stage 1 tumor and received breast-conserving surgery (77.4%); 51 patients (4.9%) were receiving active treatment (chemo- and/or radiotherapy) for breast cancer (Table 2). Median time between completion of the most recent pre–COVID-19 questionnaire and the COVID-19 survey was 4 months (IQR = 3-6).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of inclusion of study participants from UMBRELLA cohort. Patients and survivors who did not fill out the COVID-19 questionnaire completely (n = 23) were considered nonresponders. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; UMBRELLA cohort = Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaluation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of responders and nonresponders of the COVID-19–specific online survey that was sent to active UMBRELLA breast cancer cohort participants who were enrolled between October 2013 and April 2020.

| Baseline characteristicsa | Responders | Nonresponders |

|---|---|---|

| Total, No. (%) | 1051 (65.9) | 544 (34.1) |

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Mean age (SD), y | 56 (9.8) | 55 (10.4) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Female | 1045 (99.4) | 542 (99.6) |

| Male | 6 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| Mean body mass index (SD),b kg/m2 | 26.2 (4.7) | 26.2 (5.0) |

| Missing, No. (%) | 16 (1.5) | 54 (9.9) |

| Smoking, No. (%) | ||

| Smoker | 48 (4.6) | 38 (7.0) |

| Previous smoker | 531 (50.5) | 242 (44.5) |

| Nonsmoker | 461 (43.9) | 217 (39.9) |

| Unknown | 11 (1.0) | 47 (8.6) |

| Highest educational level, No. (%) | ||

| No education | 6 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| Primary school | 9 (0.9) | 7 (1.3) |

| Prevocational secondary education | 134 (12.7) | 64 (11.8) |

| Senior general or pre-university secondary education | 82 (7.8) | 40 (7.4) |

| Secondary vocational education | 228 (21.7) | 139 (25.6) |

| Higher professional education | 374 (35.6) | 153 (28.1) |

| University degree | 207 (19.7) | 92 (16.9) |

| Unknown | 11 (1.0) | 47 (8.6) |

| Median time since diagnosis, months (IQR) | 24 (6-42) | 24 (6-42) |

| Unknown, No. (%) | 9 (0.9) | 43 (7.9) |

| Tumor characteristics | ||

| Pathological T stadium, No. (%) | ||

| 0 | 66 (6.3) | 44 (8.1) |

| In situ | 92 (8.8) | 56 (10.3) |

| I | 585 (55.7) | 301 (55.3) |

| II | 211 (20.1) | 100 (18.4) |

| III | 22 (2.1) | 16 (2.9) |

| IV | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.6) |

| X | 23 (2.2) | 7 (1.3) |

| Unknown | 51 (4.9) | 17 (3.1) |

| Pathological N stadium, No. (%) | ||

| X | 66 (6.3) | 23 (4.2) |

| 0 | 606 (57.7) | 329 (60.5) |

| I | 268 (25.5) | 145 (26.7) |

| II | 25 (2.4) | 10 (1.8) |

| III | 7 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) |

| Unknown | 79 (7.5) | 35 (6.4) |

| Treatment characteristics | ||

| Type of breast surgery, No. (%) | ||

| Breast-conserving therapy | 813 (77.4) | 440 (80.9) |

| Mastectomy | 94 (8.9) | 50 (9.2) |

| Mastectomy with direct breast reconstruction | 93 (8.8) | 43 (7.9) |

| No breast surgery | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Unknown | 49 (4.7) | 10 (1.8) |

| Most invasive axillary treatment, No. (%) | ||

| Sentinel node procedure | 784 (74.6) | 420 (77.2) |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | 82 (7.8) | 40 (7.3) |

| Unknown or not performed | 185 (17.6) | 84 (15.5) |

| Systemic therapy,c No. (%) | ||

| No systemic therapy | 206 (19.6) | 169 (31.1) |

| Chemotherapy | 119 (11.3) | 73 (13.4) |

| Endocrine therapy | 282 (26.8) | 182 (33.5) |

| Immunotherapy | 73 (6.9) | 19 (3.5) |

| Combination of above | 49 (4.7) | 63 (11.6) |

| Other | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.7) |

| Unknown | 318 (30.3) | 34 (6.2) |

| Radiation therapy, No. (%) | ||

| Local | 678 (64.5) | 361 (66.4) |

| Locoregionald | 244 (23.2) | 141 (25.9) |

| Other or type unknown | 42 (4.0) | 6 (1.1) |

| No radiation therapy | 17 (1.6) | 8 (1.5) |

| Unknown | 70 (6.7) | 28 (5.1) |

As a result of rounding, percentages may not add up to a 100%. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; IQR = interquartile range, UMBRELLA = Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaLuAtion.

Calculated as weight divided by height2.

Pre- and/or postoperative therapy.

Including supraclavicular and/or axillary lymph nodes.

Table 2.

COVID-19–specific questionnaire (n = 1051).

| COVID-19 specific questionsa | Total No. patients and survivors (N = 1051) | Patients and survivors under active treatmentb (n = 51) | Patients and survivors without active treatmentb (n = 1000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Are/were you infected by COVID-19? | |||

| Yes, confirmed by nasopharyngeal swab | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Possibly, I have or had fever | 100 (9.5) | 1 (2.0) | 99 (9.9) |

| No, I was tested negative | 9 (0.9) | 2 (3.9) | 7 (0.7) |

| No, I had/have no symptoms and I was not tested | 941 (89.5) | 48 (94.1) | 893 (89.3) |

| Do the current COVID-19 measure affect your current treatment, care or aftercare? | |||

| Yes | 286 (27.2) | 17 (33.3) | 269 (26.9) |

| No | 765 (72.8) | 34 (66.7) | 731 (73.1) |

| Do you expect that the current COVID-19 measures will affect your treatment, care or aftercare in the future? | |||

| Yes | 250 (23.8) | 18 (35.3) | 232 (23.2) |

| No | 801 (76.2) | 33 (64.7) | 768 (76.8) |

| Did the threshold to contact your general practitioner change because of the COVID-19 situation? | |||

| Yes, I contact my general practitioner more easily | 19 (1.8) | 2 (3.9) | 17 (1.7) |

| Yes, I contact my general practitioner less easily | 327 (31.1) | 6 (11.8) | 231 (32.1) |

| No | 705 (67.1) | 43 (84.3) | 662 (66.2) |

| Did the threshold to contact the physicians treating your breast cancer change because of the COVID-19 situation? | |||

| Yes, I contact my breast cancer physician(s) more easily | 8 (0.8) | 1 (2.0) | 7 (0.7) |

| Yes, I contact my breast cancer physician(s) less easily | 162 (15.4) | 4 (7.8) | 158 (15.8) |

| No | 881 (83.8) | 46 (90.2) | 835 (83.5) |

| Did the threshold to discuss your breast cancer diagnosis or breast cancer (treatment)-related symptoms with family and friends change because of the COVID-19 situation? | |||

| Yes, I contact my friends and family more easily | 14 (1.3) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Yes, I contact my friends and family less easily | 87 (8.3) | 6 (11.8) | 81 (8.1) |

| No | 950 (90.4) | 44 (86.3) | 906 (90.6) |

| Are you worried about your financial situation as a result of COVID-19? | |||

| Not at all | 663 (63.1) | 31 (60.8) | 632 (63.2) |

| A little bit | 320 (30.4) | 19 (37.3) | 301 (30.1) |

| Quite a bit | 53 (5.0) | 1 (2.0) | 52 (5.2) |

| Very much | 15 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (1.5) |

As a result of rounding, percentages may not add up a 100%. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Active treatment includes chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.

Physical and Psychosocial Well-being During COVID-19

In total, 1 (0.1%) survivor had confirmed COVID-19 infection, and 100 (9.5%) patients and survivors indicated to have been possibly infected as they experienced symptoms of fever, without having been tested for the virus. Of all patients and survivors, 27.2% (n = 286) felt that the COVID-19 measures affected their current treatment, care or aftercare, and 23.8% (n = 250) felt that these measures were likely to affect their care or aftercare in the future (Table 2).

Almost one-third (31.1%, n = 327) reported a higher threshold to contact their general practitioner because of the COVID-19 outbreak, and 162 patients and survivors (15.4%) indicated to be less likely to contact their breast cancer physician. Family and friends were contacted less easily by 87 patients and survivors (8.3%). Most patients and survivors (n = 983, 93.5%) were not worried or were a little bit worried about their financial situation as a result of COVID-19 (Table 2).

During the pandemic, 48.0% (95% CI = 45.0% to 51.1%; n = 505) reported loneliness, of whom 38.9% (95% CI = 36.0% to 41.9%; n = 409) reported moderate feelings of loneliness, and 9.1% (95% CI = 7.5% to 11.0%; n = 96) reported severe loneliness (Table 3). A total of 40.0% (95% CI = 35.7% to 44.4%; n = 202) felt socially lonely, and 78.4% (95% CI = 74.6% to 81.9%; n = 396) felt emotionally lonely.

Table 3.

Comparison of crude HADS scores of all patients and survivors who completed the same questionnaire during and within 2 years before COVID-19 (n = 942), and loneliness scores during COVID-19a (n = 1051).

| Crude HADS and Loneliness scores | Before COVID-19b | During COVID-19 | z | P c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADSd median (IQR) | ||||

| Total | 7 (4-11) | 8 (5-12) | −6.87 | <.001 |

| Anxiety | 4 (3-7) | 4 (3-6) | −0.58 | .56 |

| Depression | 2 (1-5) | 3 (2-6) | −11.60 | <.001 |

| De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale,e No. [%] (95% CI) | ||||

| Not lonely | —a | 546 [52.0] (48.9 to 55.0) | — | — |

| Moderately lonely | —a | 409 [38.9] (36.0 to 41.9) | — | — |

| Severely lonely | —a | 96 [9.1] (7.5 to 11.0) | — | — |

Loneliness scores were only measured during COVID-19. CI = confidence interval; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; HADS = hospital anxiety and depression score; IQR = interquartile range.

Last valid score measured within the last 2 years before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Crude median HADS scores were compared with a 2-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

A HADS total score >7 indicates a possible anxiety disorder or depression and a score >11 indicates a probable depression or anxiety disorder.

Scores between 2 and 4 represent moderate loneliness, a score >4 represents severe loneliness.

PROs Before and During COVID-19

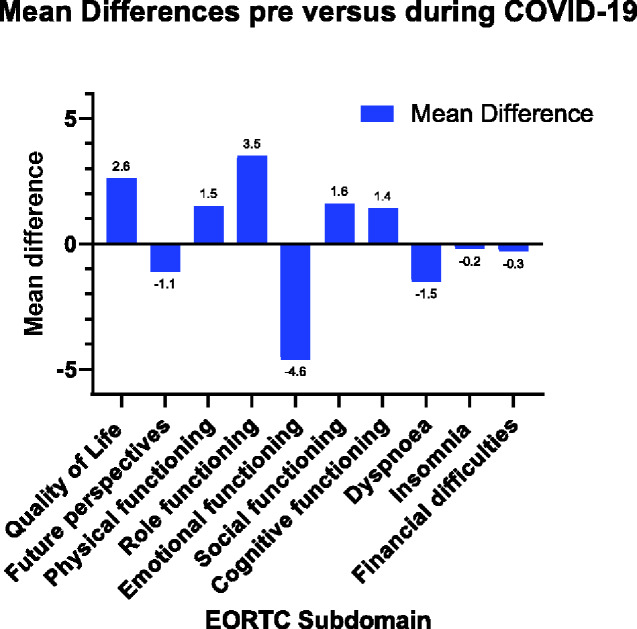

For 1022 patients and survivors (97.2%), pre- and during COVID-19 EORTC scores (Figure 2) could be compared, and for 942 (89.6%), pre- and during COVID-19 HADS scores could be compared. Overall, mean scores for the EORTC subdomains QoL, physical, and role functioning statistically significantly improved during COVID-19 (Table 4). Mean scores for the EORTC subdomain emotional functioning worsened statistically significantly from 82.6 (18.7) to 77.9 (17.3; P < .001). Also, median HADS total score and depression score deteriorated statistically significantly during COVID-19 (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Mean differences between crude mean scores before and during the COVID-19 pandemic on the EORTC QLQ-C30/BR23subdomains (n = 1022). COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; EORTC = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; QLQ C30/BR23 = core and breast cancer-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Table 4.

Comparison of crude mean EORTC scores of all patients and survivors who completed the same questionnaire during and within 2 years before COVID-19 (n = 1022).

| Crude mean EORTC scoresa | Before COVID-19b | During COVID-19 | Mean difference (95% CI) | P c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EORTC-QLQ30 and BR23, mean (SD) | ||||

| Quality of life (QoL) | 76.3 (18.2) | 78.9 (16.6) | 2.6 (-3.6 to -1.6) | <.001 |

| Future perspectives (FP) | 70.8 (24.9) | 69.7 (20.0) | −1.1 (-0.2 to 2.4) | .09 |

| Functioning scales | ||||

| Physical functioning (PF) | 87.0 (15.1) | 88.6 (14.0) | 1.5d (-2.2 to -0.9) | <.001 |

| Role functioning (RF) | 78.3 (26.3) | 81.8 (23.6) | 3.5 (-5.1 to -1.9) | <.001 |

| Emotional functioning (EF) | 82.6 (18.7) | 77.9 (17.3) | −4.6 (3.6 to 5.6) | <.001 |

| Social functioning (SF) | 86.8 (20.8) | 88.5 (20.2) | 1.6d (-2.9 to -0.4) | .01 |

| Cognitive functioning (CF) | 80.8 (20.9) | 82.2 (18.3) | 1.4 (-2.4 to -0.4) | .004 |

| Symptom scales | ||||

| Dyspnea (D) | 12.0 (21.6) | 10.5 (18.6) | −1.5 (0.3 to 2.7) | .01 |

| Insomnia (I) | 27.3 (28.3) | 27.1 (26.5) | −0.2 (-1.5 to 1.8) | .85 |

| Financial difficulties (FD) | 6.2 (16.6) | 5.9 (16.0) | −0.3 (-0.6 to 1.2) | .57 |

EORTC QLQ-C30/BR23 scores range from 0 to 100. Higher scores represent better outcomes for QoL, FP, and functioning scales, and lower scores on symptom scales indicate better outcomes. CI = Confidence Interval; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; EORTC QLQ-C30/BR23= European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer core and breast cancer-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Last valid score measured within the last 2 years before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Crude mean EORTC scores were compared with a 2-sided paired samples t test.

Mean difference differs from difference between mean scores because of rounding.

In the subgroup of actively treated patients, there was a strong and statistically significant drop in social functioning of 16.0 points during COVID-19 after adjustment for age, type of radiotherapy, and type of surgery in mixed model analysis (77.3 [95% CI = 69.4 to 85.2] to 61.3 [95% CI = 52.6 to 70.1]; P = .002; Table 5).

Table 5.

Mixed model analyses in complete cases showing the effect of COVID-19 on different EORTCa subdomains of quality of life per follow-up period.

| Group | No active treatment |

Active treatment (n = 47) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <24 months follow-up (n = 441) |

24-60 months follow-up (n = 430) |

>60 months follow-up (n = 104) |

||||||

| Meanb (95% CI) | Mean difference between groups | Meanb (95% CI) | Mean difference between groups | Meanb (95% CI) | Mean difference between groups | Meanb (95% CI) | Mean difference between groups | |

| Quality of life | ||||||||

| Pre-COVID-19 | 73.3 (71.6 to 75.0) | Referent | 79.2 (77.6 to 80.8) | Referent | 79.6 (76.2 to 82.9) | Referent | 69.9 (63.6 to 76.1) | Referent |

| During COVID-19 | 78.6 (77.1 to 80.1) | 5.3c | 79.8 (78.3 to 81.4) | 0.6 | 80.0 (76.7 to 83.2) | 0.4 | 70.0 (64.3 to 75.7) | 0.2d |

| Physical functioning | ||||||||

| Pre-COVID-19 | 86.9 (85.5 to 88.3) | Referent | 88.0 (86.7 to 89.3) | Referent | 85.0 (81.6 to 88.4) | Referent | 84.0 (78.4 to 89.5) | Referent |

| During COVID-19 | 89.4 (88.2 to 90.6) | 2.5c | 88.8 (87.6 to 90.0) | 0.8c | 88.0 (84.6 to 91.4) | 3.0c | 79.9 (74.0 to 85.7) | −4.1 |

| Role Functioning | ||||||||

| Pre-COVID-19 | 73.4 (70.8 to 75.9) | Referent | 83.4 (81.3 to 85.5) | Referent | 84.1 (79.5 to 88.8) | Referent | 66.0 (55.8 to 76.2) | Referent |

| During COVID-19 | 81.3 (79.2 to 83.4) | 7.9c | 84.3 (82.2 to 86.3) | 0.9 | 83.7 (79.0 to 88.4) | −0.5d | 61.0 (52.1 to 69.8) | −5.0 |

| Emotional functioning | ||||||||

| Pre-COVID-19 | 80.2 (78.3 to 82.0) | Referent | 84.6 (83.0 to 86.1) | Referent | 86.4 (82.8 to 90.0) | Referent | 78.0 (71.9 to 84.2) | Referent |

| During COVID-19 | 77.0 (75.4 to 78.7) | −3.1c,d | 78.1(76.6 to 79.7) | −6.4c,d | 82.2 (79.1 to 85.3) | −4.2c | 75.2 (70.4 to 80.0) | −2.8 |

| Social Functioning | ||||||||

| Pre-COVID-19 | 83.6 (81.5 to 85.7) | Referent | 90.4 (88.8 to 92.0) | Referent | 90.1 (86.2 to 94.0) | Referent | 77.3 (69.4 to 85.2) | Referent |

| During COVID-19 | 87.1 (85.3 to 89.0) | 3.5c | 91.9 (90.4 to 93.5) | 1.6d | 92.0 (88.2 to 95.8) | 1.9 | 61.3 (52.6 to 70.1) | −16.0c |

| Insomnia | ||||||||

| Pre-COVID-19 | 28.8 (26.1 to 31.5) | Referent | 26.6 (24.0 to 29.2) | Referent | 21.2 (15.9 to 26.4) | Referent | 32.6 (24.2 to 41.0) | Referent |

| During COVID-19 | 28.0 (25.5 to 30.5) | −0.8 | 26.6 (24.1 to 29.0) | <0.01 | 23.4 (19.0 to 27.8) | 2.2 | 31.9 (23.6 to 40.2) | −0.7 |

EORTC QLQ C30 scores range from 0 to 100. For quality of life and functioning scales, a higher score indicates a better outcome. For insomnia, a lower score indicates a better outcome. CI = confidence interval; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; EORTC QLQ-C30 = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer core Quality of Life Questionnaire; MD = mean difference (difference in mean scores between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19).

Mean scores were adjusted for age (linear). In addition, active treatment scores were adjusted for type of radiotherapy and type of surgery.

Statistically significant difference with a P value less than .05.

Mean difference differs from difference between mean scores because of rounding.

Among the nonactively treated patients and survivors, age-adjusted analyses showed that emotional functioning worsened statistically significantly in all groups, whereas physical functioning improved statistically significantly in all groups (Table 5). QoL, role, and social functioning improved statistically significantly in nonactively treated patients and survivors who were enrolled in UMBRELLA for less than 24 months (Table 5).

PROs Before and During COVID-19 Among Patients and Survivors With Suspected COVID-19 Infection

Within the subgroup of 100 patients and survivors with suspected COVID-19 infection, we found statistically significant worsening in mean [SD] QoL (75.8 [18.2] to 65.9 [18.7]; P < .001) and emotional functioning (81.6 [21.5] to 74.8 [19.9]; P < .001) and an increase in dyspnea score [SD] (11.3 [20.5] to 19.0 [23.8]; P = .008) when compared with pre-COVID-19. EORTC scores for cognitive, physical, role, and social functioning, as well as insomnia and financial and future perspectives, remained stable. Median total HADS score and median HADS anxiety score [IQR] increased slightly (7 [4-11] to 8 [5-13]; P < .001; and 4 [3-7] to 5 [3-7]; P = .15, respectively). Median HADS depression score [IQR] increased from 2 [1-5] to 4 [ 2-7] (P < .001).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has a substantial impact on patients previously or currently being treated for breast cancer. One in 3 reported to be less likely to contact their general practitioner, and 15.4% indicated to be less likely to contact their breast cancer physician because of barriers induced by COVID-19 restrictions. In patients actively receiving treatment, social functioning decreased substantially, and in patients and survivors who were no longer receiving active treatment, deterioration of emotional functioning was observed. Loneliness was reported by almost half of all patients and survivors.

The high proportion who indicated experiencing a higher barrier to contact their general practitioner (31.1%) is in line with the upsetting findings of the Dutch cancer registry (NKR), who reported a nationwide decrease up to 40% in cancer diagnoses during COVID-19 (16). Jones and colleagues (28) (United Kingdom) also expressed their concerns about patients potentially feeling higher barriers to consult a general practitioner for nonspecific symptoms. Patients might experience (moral) dilemmas, including concerns about wasting the physician’s time, insufficient capacity, or exposure to the virus in a healthcare institution (15). Moreover, an average referral drop of 37% to all medical specialties was observed in the Netherlands during the outbreak (29). Fortunately, most patients and survivors (84.6%) did not report a higher barrier to reach out to their breast cancer physician. Thus, although the threshold to contact a general physician was higher in a concerning proportion of patients and survivors, the pandemic seemed to have minimal impact on interaction with the breast cancer team once diagnosed. This does highlight the importance of creating public awareness about the risk potential delays in seeking medical help could cause, aiming to lower barriers for patients and survivors to contact their general practitioner when experiencing nonbreast cancer–related symptoms (16).

In addition to the decrease in cancer diagnoses during the pandemic, a decrease in mental health also raises concerns about future disease outcomes. Previous studies showed that lower levels of anxiety and depression, as well as social support, seem to positively affect treatment adherence (30,31).

Among patients who were receiving active breast cancer treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic, a major clinically and statistically significant decrease in social functioning was observed (Table 5) (32). The mean score approached the threshold score for clinical importance of 58 (33). One explanation for this decrease could be that these patients and survivors were more careful regarding social interaction. Recent publications underlining the risk of COVID-19–related adverse events in cancer patients might have amplified concerns about contracting the virus (9,15,34-36).

All nonactively treated patients and survivors showed a statistically significant reduction in emotional functioning. This domain assesses anxiety, depression, and general distress through questions about feeling tense, worrying, feeling depressed, and feeling irritable (37). The deterioration in this domain is likely attributable to COVID-19, because we know from pre–COVID-19 measurements in the same UMBRELLA cohort that emotional functioning generally increases over time [previously shown in Supplementary Data (available online) by Gregorowitsch and colleagues (38)]. Also, the median score for depression worsened statistically significantly during COVID-19. Concerns about the new viral threat might have enhanced overall uncertainty in individuals. Different types of coping mechanisms could play a role here; lower tolerance of uncertainty is related to higher appraisal of a health threat and higher levels of emotion-focused coping strategies (39). A previous study showed that, during the 2009 H1N1 viral outbreak, emotion-focused coping was related with increased levels of depression (39).

Interestingly, despite the deterioration in emotional functioning in all nonactively treated patients and survivors, there was a statistically significant increase in global QoL, role functioning, social functioning, and physical functioning. For QoL, physical and social functioning, the increases did not reach the minimal clinically important difference scores (10, 7, and 7, respectively) (32). Although cautiousness is therefore advised when interpreting these results, they do emphasize that, regardless the COVID-19 pandemic, PROs did not deteriorate in these domains. This may partly be explained by the fact that these PROs generally tend to increase over time since diagnosis (38). In our study, however, median time between pre- and during COVID-19 PROs was only 4 months. Furthermore, the shared crisis may put patients’ and survivors’ perceived QoL in relation to their disease in a different perspective and may even accelerate reconceptualization of their QoL (40). The observed increase in social and role functioning suggests that patients and survivors reported an increased ability to fulfill responsibilities associated with occupational and/or family roles. Governmental measures encouraging working from home and prohibiting social events (ie, less social obligations) in times of social distancing or lockdown may also play a role.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic seemed worse among patients and survivors with suspected COVID-19 infection. The largest effect was seen in a substantial drop in QoL and an increase in symptoms of dyspnea and depression. This is in line with the findings of our Italian colleagues (41), who reported worsening of QoL in 44.1% of patients 60 days after the onset of the first COVID-19 symptoms (n = 143). This may partly be explained by the fact that this subgroup will have likely experienced a more profound period of self- or imposed isolation.

In general, experiencing health problems can induce loneliness and vice versa (42). Moreover, a recent meta-analysis showed that breast cancer patients and survivors might be particularly vulnerable for feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and depression when compared with patients without prior cancer (19). Social isolation measures to fight the COVID-19 pandemic might enhance these feelings. This study showed that 48.0% felt lonely, of whom the majority felt emotionally lonely. Loneliness is not a parameter that was captured routinely in the UMBRELLA cohort, so there were no pre–COVID-19 measurements on loneliness. Furthermore, because we did not include a noncancer control group, it remains unclear whether patients previously or currently being treated for breast cancer are more severely affected by COVID-19 than the general population. Nonetheless, the reported proportion of 48.0% loneliness is substantially higher than the reported 34% in the general Dutch population in 2019 (pre–COVID-19), as measured by the same loneliness scale (Statistics Netherlands; n = 7398) (43). Also, our proportion of patients and survivors feeling lonely was substantially higher than the reported 30%-35% cancer patients in a study conducted pre–COVID-19 (44). Moreover, our percentage of patients and survivors feeling severely lonely was strikingly high; almost 10% compared with 0%-2% in other studies performed among cancer patients (42). Thus, even though we cannot rule out other contributing factors, the higher proportion feeling lonely in this breast cancer population is likely due to the COVID-19 measures.

The results of this study underline the magnitude of the impact of a major health crisis on the psychosocial well-being of breast cancer patients and survivors. With the high survival rates of breast cancer patients, mental health has become an integral focus of supportive treatment. However, a barrier to e-mental health still exists (11,45). Triggered by the ongoing pandemic, several e-mental health initiatives were developed in the Netherlands (ie, facilitation of video consultation or the Red Cross COVID-19 helpline for mental care during isolation or quarantine). However, at the time of this survey, breast cancer patients and survivors did not have regular access to digital mental health services. Especially in times when face-to-face contact is not an option and when the global need for psychological and/or peer support is rising because of the viral threat, efforts are needed to rapidly implement e-mental health screening programs and digital psychological interventions. Only by adapting to the new circumstances will we be able to treat both ongoing and emerging mental health care conditions due to COVID-19 and prevent long-term problems (11,46). Considering that a second wave of COVID-19 or another future outbreak with similar impact is probable (15,47), and now that the pandemic seems to be lingering, one would hope that the current experiences during this pandemic may serve as a turning point in the adoption and acceptance of successful e-mental health applications (45,48).

A limitation of this study is the fact that only 51 patients and survivors (4.9%) in our cohort received active treatment during COVID-19, causing relatively wide 95% confidence intervals in this group. As a consequence, the results of this study mainly show the impact of COVID-19 on breast cancer survivors, whereas the impact of COVID-19 might be more severe for newly diagnosed patients who experienced adjusted treatment protocols. However, as breast cancer survivors account for the largest group of cancer survivors in high-income countries (19), and a clinically significant proportion of breast cancer survivors still consider themselves patients 5-15 years postdiagnosis (49), we believe these results are valuable for an important part of the general population. Second, this study measured the impact of COVID-19 6 weeks after the start of COVID-19. Therefore, it is unclear whether our results represent short-term or longer-lasting effects. However, previous literature on the 2009 H1N1 viral threat showed that psychological effects can persist until 30 months after the outbreak (39). Last, we could not compare the impact of COVID-19 on patients previously or currently being treated for breast cancer to the impact on a healthy reference population. Nonetheless, these results contain important clinically relevant information that may be used to improve understanding the needs and experiences of breast cancer patients and survivors amid these exceptional times. An important strength of this study is that the UMBRELLA cohort provided a unique opportunity to longitudinally compare PROs during COVID-19 with PROs before COVID-19 in an identical population in a representative population of breast cancer patients and survivors (20).

In conclusion, COVID-19 is having a substantial impact on breast cancer patients and survivors. Emotional functioning deteriorated in nonactively treated patients and survivors following the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 in 2 patients and survivors reported loneliness that was moderate or severe, and 1 in 3 reported to be less likely to contact their healthcare providers. In actively treated patients, social functioning decreased substantially.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research (including study design; data collection, analysis, interpretation of data; and writing of the report), authorship, and/or (the decision to submit the article for) publication.

Notes

Role of the funder: Not applicable.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author contributions: The corresponding author (HM Verkooijen) confirms that she had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Each author has contributed significantly to, and is willing to take public responsibility for, the following aspects of the study: Design: CA Bargon, MCT Batenburg, LE van Stam, DR Mink van der Molen, W Maarse, N Vermulst, IE van Dam, F van der Leij, EJP Schoenmaeckers, MF Ernst, IO Baas, T van Dalen, R Bijlsma, DA Young-Afat, A Doeksen, HM Verkooijen. Data acquisition: CA Bargon, MCT Batenburg, LE van Stam, DR Mink van der Molen, A Doeksen, HM Verkooijen. Analyses: CA Bargon, MCT Batenburg, LE van Stam, DR Mink van der Molen, DA Young-Afat, HM Verkooijen. Interpretation: CA Bargon, MCT Batenburg, DR Mink van der Molen, DA Young-Afat, HM Verkooijen. Drafting: CA Bargon, LE van Stam. Critical revision: CA Bargon, MCT Batenburg, LE van Stam, DR Mink van der Molen, W Maarse, N Vermulst, IE van Dam, F van der Leij, EJP Schoenmaeckers, MF Ernst, IO Baas, T van Dalen, R Bijlsma, DA Young-Afat, A Doeksen, HM Verkooijen.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Janet van Dasselaar for her support with the clinical data management and Rosalie van den Boogaard for support with institutional review board approval. We are greatly indebted to the medical ethics committee of the UMC Utrecht for expedited ethical review of the protocol.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Wang H, Zhang L. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):e181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fleming TR, Labriola D, Wittes J. Conducting clinical research during the COVID-19 pandemic: protecting scientific integrity. JAMA. 2020;324(1):33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haffajee RL, Mello MM. Thinking globally, acting locally–the U.S. response to Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Studdert DM, Hall MA. Disease control, civil liberties, and mass testing–calibrating restrictions during the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):102-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abu Hilal M, Besselink MG, Lemmers DHL, Taylor MA, Triboldi A. Early look at the future of healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020;107(7):e197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 8. Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049-2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marandino L, Necchi A, Aglietta M, Maio MD. COVID-19 emergency and the need to speed up the adoption of electronic patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical practice. J Clin Oncol Pract. 2020;16(6):295-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fraher EP, Pittman P, Frogner BK, et al. Ensuring and sustaining a pandemic workforce. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2181-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu R, Sundaresan T, Reed ME, Trosman JR, Weldon CB, Kolevska T. Telehealth in oncology during the COVID-19 outbreak: bringing the house call back virtually. J Clin Oncol Pract. 2020;16(6):289-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Lancet Oncology. COVID-19: global consequences for oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Livingston EH. Surgery in a time of uncertainty: a need for universal respiratory precautions in the operating room. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khullar D, Bond AM, Schpero WL. COVID-19 and the financial health of US hospitals. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The Lancet Oncology. Safeguarding cancer care in a post-COVID-19 world. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dinmohamed AG, Visser O, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):750-751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sowa M, Głowacka-Mrotek I, Monastyrska E, et al. Assessment of quality of life in women five years after breast cancer surgery, members of breast cancer self-help groups–non-randomized, cross-sectional study. Contemp Oncol. 2018;22(1):20-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Legg MA-O, Hyde MK, Occhipinti S, Youl PH, Dunn J, Chambers SK. A prospective and population-based inquiry on the use and acceptability of peer support for women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(2):677-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carreira H, Williams R, Müller M, Harewood R, Stanway S, Bhaskaran K. Associations between breast cancer survivorship and adverse mental health outcomes: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(12):1311-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Young-Afat DA, van Gils CH, van den Bongard H, Verkooijen HM; on behalf of the UMBRELLA Study Group. The Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long-term evaLuAtion (UMBRELLA): objectives, design, and baseline results. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;164(2):445-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gal R, Monninkhof EM, van Gils CH, et al. The trials within cohorts design faced methodological advantages and disadvantages in the exercise oncology setting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;113:137-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fayers P, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 3rd ed Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spinhoven PH, Ormel J, Sloekers PPA, Kempen GIJM, Speckens AEM, Van Hemert AM. A validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):363-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Jong Gierveld J, van Tilburg T. [A shortened scale for overall, emotional and social loneliness]. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;39(1):4-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Jong Gierveld J, van Tilburg TG. Manual of the loneliness scale. VU University Amsterdam, Department of Social Research Methodology. Updated from the printed version: Updated 2020. https://home.fsw.vu.nl/tg.van.tilburg/manual_loneliness_scale_1999.html. Accessed May 2, 2020.

- 28. Jones D, Neal RD, Duffy SRG, Scott SE, Whitaker KL, Brain K. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the symptomatic diagnosis of cancer: the view from primary care. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):748-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. ZorgDomein. [ZorgDomein heeft actuele cijfers over zorgbehandelingen die zich opstapelen door corona crisis]; 2020. https://zorgdomein.com/nieuws/actuele-cijfers-uitgestelde-zorg-coronavirus/. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- 30. Theofilou P, Panagiotaki H. A literature review to investigate the link between psychosocial characteristics and treatment adherence in cancer patients. Oncol Rev. 2012;6(1):e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bender CM, Gentry AL, Brufsky AM, et al. Influence of patient and treatment factors on adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(3):274-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Musoro JZ, Coens C, Fiteni F, et al. Minimally important differences for interpreting EORTC QLQ-C30 scores in patients with advanced breast cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3(3):pkz037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Giesinger JM, Loth FLC, Aaronson NK, et al. Thresholds for clinical importance were established to improve interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice and research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;118:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335-337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sahu KK, Jindal V, Siddiqui AD. Managing COVID-19 in patients with cancer: a double blow for oncologists. J Clin Oncol Pract. 2020;16(5):223-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jazieh A-R, Alenazi TH, Alhejazi A, Safi FA, Olayan AA. Outcome of oncology patients infected with coronavirus. J Clin Oncol Global Oncol. 2020;6:471-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gamper EM, Groenvold M, Petersen MA, et al. ; on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. The EORTC emotional functioning computerized adaptive test: phases I-III of a cross-cultural item bank development. Psycho‐Oncology. 2014;23(4):397-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gregorowitsch ML, van den Bongard HJGD, Young-Afat DA, et al. Severe depression more common in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ than early-stage invasive breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;167(1):205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Taha S, Matheson K, Cronin T, Anisman H. Intolerance of uncertainty, appraisals, coping, and anxiety: the case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Br J Health Psychol. 2014;19(3):592-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(11):1507-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; for the Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Deckx L, van den Akker M, Buntinx F. Risk factors for loneliness in patients with cancer: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(5):466-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Statistics Netherlands (CBS). Nearly 1 in 10 Dutch people frequently lonely in 2019; 2020. https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2020/13/nearly-1-in-10-dutch-people-frequently-lonely-in-2019. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- 44. Deckx L, van den Akker M, van Driel M, et al. Loneliness in patients with cancer: the first year after cancer diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2015;24(11):1521-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wind TR, Rijkeboer M, Andersson G, Riper H. The COVID-19 pandemic: the ‘black swan’ for mental health care and a turning point for e-health. Internet Interv. 2020;20:100317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(4):317-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leung K, Wu JT, Liu D, Leung GM. First-wave COVID-19 transmissibility and severity in China outside Hubei after control measures, and second-wave scenario planning: a modelling impact assessment. Lancet. 2020;395(10233):1382-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shachar C, Engel J, Elwyn G. Implications for telehealth in a postpandemic future: regulatory and privacy issues. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thong MSY, Wolschon EM, Koch-Gallenkamp L. “Still a cancer patient”-associations of cancer identity with patient-reported outcomes and health care use among cancer survivors. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;2(2):pky031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nationaal Borstkankeroverleg Nederland (NABON). [Landelijke richtlijn Mammacarcinoom]; 2012. https://heelkunde.nl/sites/heelkunde.nl/files/richtlijnen-definitief/Mammacarcinoom2012.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- 51. Dutch Society of Surgical Oncology (NVCO). [Handvat voor chirurgische ingrepen tijdens Corona-crisis]; 2020. https://heelkunde.nl/nieuws/handvat-voor-chirurgische-ingrepen-tijdens-corona-crisis. Accessed May 13, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.