Abstract

Background

Healthcare workers (HCWs) and other essential workers are at risk of occupational infection during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several infection control strategies have been implemented. Evidence shows that universal masking can mitigate COVID-19 infection, though existing research is limited by secular trend bias.

Aims

To investigate the effect of hospital universal masking on COVID-19 incidence among HCWs compared to the general population.

Methods

We compared the 7-day average incidence rates between a Massachusetts (USA) healthcare system and Massachusetts residents statewide. The study period was from 17 March (the date of first incident case in the healthcare system) to 6 May (the date Massachusetts implemented public masking). The healthcare system implemented universal masking on 26 March, we allotted a 5-day lag for effect onset and peak COVID-19 incidence in Massachusetts was 20 April. Thus, we categorized 17–31 March as the pre-intervention phase, 1–20 April the intervention phase and 21 April to 6 May the epidemic decline phase. Temporal incidence trends (i.e. 7-day average slopes) were compared using standardized coefficients from linear regression models.

Results

The standardized coefficients were similar between the healthcare system and the state in both the pre-intervention and epidemic decline phases. During the intervention phase, the healthcare system’s epidemic slope became negative (standardized β: −0.68, 95% CI: −1.06 to −0.31), while Massachusetts’ slope remained positive (standardized β: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.94 to 1.05).

Conclusions

Universal masking was associated with a decreasing COVID-19 incidence trend among HCWs, while the infection rate continued to rise in the surrounding community.

Keywords: Hospital, infection control, infectious disease, personal protective equipment, SARS-CoV-2

Key learning points.

What is already known about this subject:

Healthcare workers are occupationally exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

Protecting healthcare workers and other essential workers is important to maintain healthcare and other essential businesses.

Optimal personal protective equipment use can minimize workers’ risk of being affected by COVID-19.

What this study adds:

Additional evidence that universal masking is associated with decreased incident COVID-19 infections among healthcare workers.

Universal masking in the healthcare setting protects healthcare workers.

What impact this may have on practice or policy:

Timely universal masking policy should be implemented and maintained in healthcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study indirectly supports universal masking with procedure masks or similar medical masks by other essential workers and within indoor businesses when social distancing and ventilation may be inadequate.

Introduction

COVID-19 is an occupational risk for healthcare workers (HCWs) essential to maintaining health and hospital systems [1]. Evidence supports HCWs’ infection risk due to direct exposure to co-workers, patients and contaminated environments [2]. Accumulating research suggests that optimal infection control strategies, including personal protective equipment (PPE), can minimize the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to HCWs [3,4]. Among now established mitigation measures, universal masking is thought to be one of the most effective means to protect HCWs. However, existing evidence of universal masking efficacy is largely based on self-comparison results (i.e. comparing pre- and post-masking phases) [5] instead of comparing HCWs with a reference population, and thus subject to secular trend bias. Therefore, we conducted this study to investigate the effect of universal masking in a Massachusetts (USA) healthcare system, using the statewide population as a comparison group.

Methods

This time-series study examined the daily COVID-19 incidence trends among the Massachusetts statewide population and the HCWs of a Massachusetts community healthcare system that tested symptomatic employees since the initial outbreak. The statewide data were derived from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health [6]. More than 95% of the system’s HCWs (4449 out of 4673) resided within Massachusetts, almost all in the seven counties of the greater Boston area, which are also home to 84% of the statewide population [7]. The HCW cohort of the healthcare system and related ethical statement are described in our previous paper [8]. In the present study, the total number of HCW incident cases is different due to a longer observation period. We calculated 7-day moving average COVID-19 incidence to smooth daily fluctuation. Each incident case was assigned the date when that HCW called the occupational health ‘hotline’ for triage. For state population cases, we assigned the reported date.

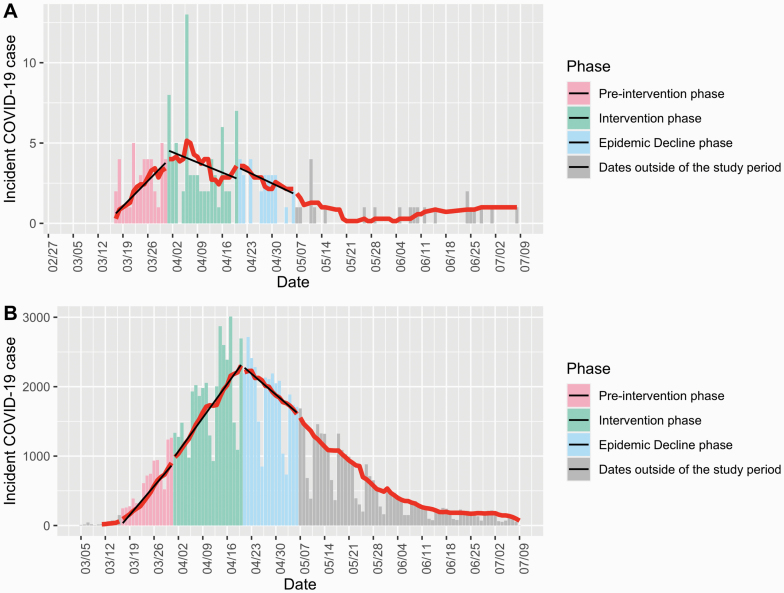

We defined the study period as from 17 March 2020, when the first case in the healthcare system was identified, to 6 May 2020. The study period was divided into three phases: pre-intervention (17–31 March), intervention (1–20 April) and epidemic decline (21 April to 6 May). Date cut-offs were determined as follows. First, the healthcare system implemented universal masking on 26 March and we allowed five more days for the policy to take effect based on the average COVID-19 incubation period. The policy included securing N95s for all direct-care staff managing confirmed/suspect COVID-19 patients and providing procedure masks to all other clinical and non-clinical staff. Second, Massachusetts reached the peak of COVID-19 incidence on 20 April (Figure 1), and the effects of universal masking are more detectable when the surrounding community secular trend is increasing. Finally, Massachusetts implemented a statewide masking policy on 6 May.

Figure 1.

Temporal distribution of COVID-19 incidence among the (A) healthcare system employees and (B) Massachusetts residents statewide. Bars indicate the absolute number of daily cases. The red line denotes the 7-day average of new cases. The black lines show linear regression slopes in each specific phase. The phases were categorized based on the implementation date of universal masking policy by the healthcare system (pre-intervention phase, 17–31 March; intervention phase, 1–20 April; epidemic decline phase, 21 April to 6 May).

We built linear regression models to investigate the temporal trends for each cohort’s 7-day average incidence within each of the three phases. Standardized beta coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated and presented to account for the different scales between the healthcare system and the state. The analyses were performed using R software (version 3.6.3) and SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute).

Results

During the study period, incident cases in the healthcare system and the state were 142 and 75 493, respectively. Pre-intervention, both the healthcare system and the state had strong increasing trends in the 7-day average COVID-19 incidence (Figure 1; Table 1) with overlapping slopes (0.96 (0.80 to 1.13) and 0.99 (0.92 to 1.07), respectively). While the temporal trend among Massachusetts residents kept increasing with a similar slope in the intervention phase (0.99 (0.94 to 1.05)), that of the healthcare system decreased and was negative (−0.68 (−1.06 to −0.31)). During epidemic decline, following the states’ pandemic peak, both populations’ incidence showed overlapping negative slopes (−0.90 (−1.19 to −0.60) and −0.99 (−1.07 to −0.92)) (Figure 1; Table 1).

Table 1.

The standardized beta coefficients of 7-day average COVID-19 incident cases regressed on days during the three study phases

| Pre-intervention phase (17–31 March) | Intervention phase (1–20 April) | Epidemic decline phase (21 April to 6 May) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The healthcare system | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.13) | −0.68 (−1.06 to −0.31) | −0.90 (−1.19 to −0.60) |

| Massachusetts statewide | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.07) | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.05) | −0.99 (−1.07 to −0.92) |

Beta coefficient (95% CI) derived from linear regression models in each phase.

Discussion

Our study provides additional evidence of the protective effect of universal masking in healthcare settings. The HCW’s epidemic curve was flattened, and in fact, demonstrated a decreasing daily incidence trend after implementing universal masking, while the statewide infection rate continued to increase during the same time period. The findings are in agreement with a recently published study using HCW self-comparison [5], finding a significant decrement in the SARS-CoV-2 positivity rate after the implementation of universal masking. We confirmed this effect by including a comparison group, eliminating potential secular trend bias that limits before and after time-series studies.

Evidence supports that PPE can prevent HCWs from being infected [9]. Two studies conducted in Wuhan, China investigated 278 and 420 front-line HCWs with optimal PPE protection from different healthcare systems, respectively, and reported no infections [3,10]. In contrast, 10 out of 213 HCWs without appropriate masking protection sustained nosocomial infection [10]. In accordance with the existing evidence [5], our results further support masking’s protective effects from the perspective of hospital infection prevention.

The current study has several strengths such as the use of a comparable reference group, a validated outcome and a distinct intervention. Nonetheless, there are some limitations. First, the current study is limited by the small sample size of HCWs, the short intervention period and individual HCW compliance with the masking policy and PPE use were not measured. The relatively small sample size during the post-intervention, epidemic decline period prevented us from detecting potential additional effects of universal masking, as statewide incidence was also strongly decreasing. In part, this was likely due to the increased use of masks within the community for grocery shopping and similar activities. Therefore, additional larger-scale studies of masking are warranted. Second, the 5-day interval assumed for the policy to take effect was not precise, but reasonable because the median lag time between symptom development and infection is 5 days [11]. Finally, there could be unmeasured confounding, such as improved social distancing, hand hygiene and isolation of COVID-19 patients. However, we found significant differences between incidence curves, with HCWs’ changing from positive to negative slopes shortly after universal masking, which is unlikely to be entirely biased.

In conclusion, our results suggest that universal masking significantly mitigates COVID-19 incidence in the healthcare setting, which may be applicable to other essential workers and indoor businesses.

Funding

None of the authors receives funding towards the present study.

Competing interests

S.N.K. has received COVID-19-related consulting fees from Open Health. All other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1. Fraher EP, Pittman P, Frogner BK et al. Ensuring and sustaining a pandemic workforce. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2181–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lan FY, Wei CF, Hsu YT, Christiani DC, Kales SN. Work-related COVID-19 transmission in six Asian countries/areas: a follow-up study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0233588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu M, Cheng SZ, Xu KW et al. Use of personal protective equipment against coronavirus disease 2019 by healthcare professionals in Wuhan, China: cross sectional study. Br Med J 2020;369:m2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Behrens GMN, Cossmann A, Stankov MV et al. Perceived versus proven SARS-CoV-2-specific immune responses in health-care professionals. Infection 2020;48:631–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang X, Ferro EG, Zhou G, Hashimoto D, Bhatt DL. Association between universal masking in a health care system and SARS-CoV-2 positivity among health care workers. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324:703–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. COVID-19 Response Reporting https://www.mass.gov/info-details/covid-19-response-reporting (10 September 2020, date last accessed).

- 7. IndexMundi. Massachusetts Population by County https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/united-states/quick-facts/massachusetts/population#table (10 September 2020, date last accessed).

- 8. Lan FY, Filler R, Mathew S et al. COVID-19 symptoms predictive of healthcare workers’ SARS-CoV-2 PCR results. PLoS One 2020;15:e0235460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lan F-Y, Fernandez-Montero A, Kales SN. COVID-19 and healthcare workers: emerging patterns in Pamplona, Asia and Boston. Occup Med (Lond). 2020;70:340– 341. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang X, Pan Z, Cheng Z. Association between 2019-nCoV transmission and N95 respirator use. J Hosp Infect 2020;105:104–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med 2020;172:577–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]