Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an acute respiratory illness caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). SARS-CoV-2 initially was identified from a cluster of patients admitted with ‘pneumonia of unknown etiology’ in late December 2019 to hospitals in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. These patients were epidemiologically linked to a seafood wholesale market where other live animals also were sold (Chen et al. 2020). Since then, 23,057,288 cases and 800,906 deaths have been reported globally in more than 200 countries as of 23 August 2020 (World Health Organization 2020). Many healthcare systems have become overwhelmed due to concomitant epidemics of COVID-19 and dengue, complicating the clinical, epidemiological, and control of both infections. This report highlights the response to COVID-19 in Bhutan and lessons learned from it for dengue control.

Bhutan confirmed its first case of COVID-19 on 5 March 2020. The patient was a 76-yr-old American tourist who contracted the virus while traveling on a cruise ship on the Brahmaputra River in Assam, India. Following this incident, the Royal Government of Bhutan has instituted aggressive public health and containment measures. Bhutan closed all its borders and schools, public markets were suspended, and non-essential services and gatherings were banned across the country to prevent local transmission of SARS-CoV-2. In a span of 22 wk from the date of the first case, 102 imported cases of COVID-19 were reported. All of these cases were detected during the mandatory 21-day quarantine period that was imposed for all travelers entering the country, according to the national pandemic preparedness guidelines.

A nation-wide lockdown was announced on 11 August 2020 following the report of a COVID-19 case detected outside the quarantine facility in one of the communities under the jurisdiction of Gelephu, located in Central Bhutan. The case was initially quarantined after returning from Middle-Eastern country. During the quarantine, she was tested five times with the reverse transcriptase (RT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for SARS-COV-2 and all results were negative. The person was released from quarantine on 28 July and traveled to their village, whereby she tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at subsequent test—14 d post discharge from quarantine (10 August). The case had close contacts with several people in a number of towns, including the capital city Thimphu, Paro, Gelephu, and on the route to the village. Simultaneously, on 12 August, an outbreak of SARS-COV-2 was declared following the detection of a cluster of cases in Phuntsholing sub-district in Chukha district. As of the current date, a total of 100 cases has been detected from Phuntsholing alone, amongst the total of 225 cases of COVID-19 reported in the country.

COVID-19 has many similar clinical features compared to dengue, which poses a potential challenge in the early detection and management of both diseases (Chen et al. 2020). As the pandemic unfolds, it has become clear that mild cases of COVID-19 are common and have symptoms similar to other viral infections. People infected with SARS-COV-2 can be asymptomatic (Kimball et al. 2020), and not all patients with COVID-19 present fever or respiratory symptoms (Chen et al. 2020). Classical signs of dengue, including petechiae and thrombocytopenia, can be common with COVID-19 (Bansal et al. 2020, Joob and Wiwanitkit 2020). Both diseases present similar laboratory parameters such as lymphopenia, leucopenia, and elevated transaminases (Henrina et al. 2020). COVID-19 cases may be misdiagnosed as dengue or other viral diseases based on initial clinical presentation of the patient and ease of access to rapid diagnostic test kits for dengue and may result in delayed diagnosis and treatment for COVID-19 (Yan et al. 2020). The deferred recognition of COVID-19 due to initial/provisional diagnosis with dengue has led to further transmission of SARS-CoV-2 due to close contacts in the healthcare setting and community (Prasitsirikul et al. 2020). Warning signs for COVID-19 include difficulty in breathing, persistent chest pain, confusion, inability to wake or stay awake and bluish lips and face (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020), while warning signs for dengue include abdominal pain/tenderness, persistent vomiting, mucosal bleeding, lethargy or restlessness, liver enlargement or elevated hematocrit concurrent with rapid decrease in platelet count (World Health Organization 2009). Such warning signs might be useful to distinguish between COVID-19 and dengue and start the course of appropriate treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic algorithm to differentiate COVID-19 and dengue in dengue-endemic settings.

Confirmed cases of co-infection of dengue and COVID-19 have been reported (Kembuan 2020, Verduyn et al. 2020). Therefore, healthcare providers need to consider both COVID-19 and dengue in the differential diagnosis of acute febrile illness in areas endemic for dengue, or in patients with recent travel to these areas, and test for both diseases. Considering COVID-19 as one of the possible diagnoses among patients with suspected dengue in tropical countries has implications for both the patient’s health outcome and the public health system.

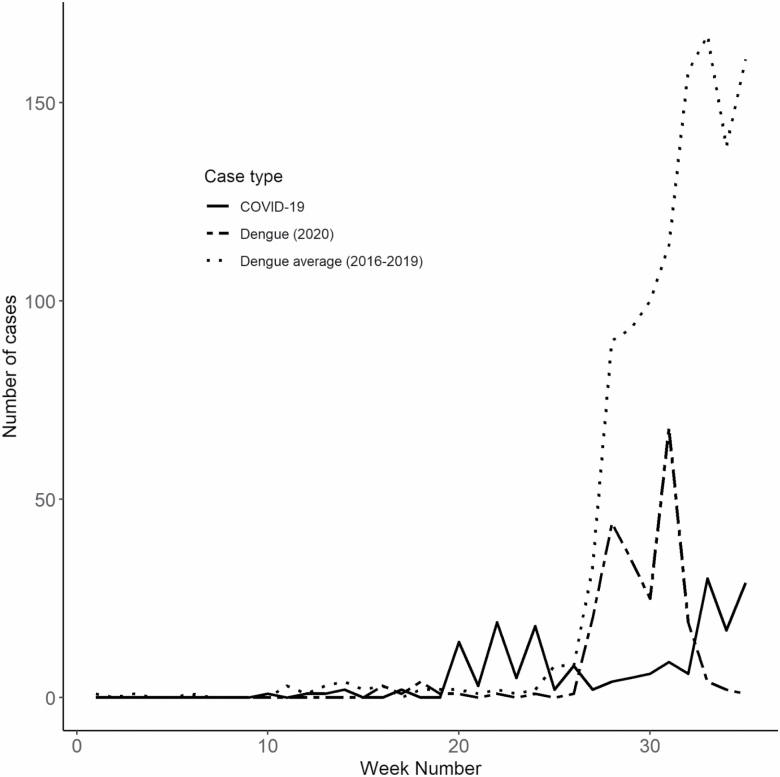

Amidst this complex epidemiological scenario, people in Bhutan have demonstrated a true sense of solidarity in the fight against COVID-19. Besides complying with the advice of the government to avoid gathering and following strict hand hygiene and cough etiquette, some private organizations have donated personal protective equipment (PPE) for the health workforce and offered free accommodation to facilitate quarantine facilities. Unprecedented number of volunteers came forward to support the government in implementing activities vital for SARS-CoV-2 control. Streets, institutions, offices, and commercial buildings laid empty as people worked remotely or ‘sheltered in place’ at home. Such concerted effort and social mobilization was not only helpful in preventing the community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 but also indirectly benefited in the control of dengue. Interestingly, only 231 cases of dengue were reported across the country in 2020, which is a ~90% reduction compared to the same time the previous year. Weekly dengue incidence in 2020 exhibited a substantial decreasing trend as compared to the average for the past 4 yr (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Number of dengue and COVID-19 cases in Bhutan up to week 35, 2020.

In Bhutan, dengue has been reported every year since the first outbreak in 2004. Vector surveillance and control through source reduction of mosquitoes, indoor residual spraying (IRS) of insecticide, thermal fogging, and health promotion activities are important methods of dengue control (Tsheten et al. 2020). These activities are routinely implemented, even during the current COVID-19 pandemic, under the auspices of the Vector-borne Disease Control Program (VDCP), Ministry of Health. The Royal Centre for Disease Control (RCDC), under the Ministry of Health, undertakes epidemiological surveillance in all health centers. Health centers across the country are required to report cases and outbreaks to the national surveillance system, known as the National Early Warning Alert and Response Surveillance (NEWARS). During this pandemic, health authorities have constantly reminded the people to stay at home and avoid visiting health facilities without genuine reason. However, essential health services have continued throughout the pandemic period. COVID-19 has drastically modified the health-seeking behavior in other countries due to fear of contagion in the population and messages from the health authorities to stay home (Dantés et al. 2020). It is not known if similar drivers in Bhutan have resulted in under-reporting and lower dengue incidence this year.

We speculate that the reduction in exposure to dengue as a result of limited human movement during the COVID-19 pandemic might have resulted in lower dengue incidence. In dengue-endemic settings, Aedes aegypti (L.) tend not to disperse far from households because human blood sources, mates, and places to lay their eggs are present around homes where they reside (Scott and Morrison 2010). The limited flight range of mosquitoes mean that rapid geographic spread of dengue during epidemics is more likely driven by movement of viremic humans rather than movement of infected mosquitoes (Scott and Morrison 2010).

Dengue incidence in other countries also has declined coinciding with the intervention measures in response to COVID-19 (Mascarenhas et al. 2020). Some states in Brazil have reported reductions in dengue incidence by more than 70% compared to the previous year (Mascarenhas et al. 2020). This drop-in incidence could be due, in part, to the reduction in numbers of people infected with arboviruses seeking healthcare due to fears about SARS-CoV-2 (Magalhaes et al. 2020). Countries not implementing effective COVID-19 containment measures appear to have had higher epidemic transmission of dengue than regions that have adopted drastic COVID-19 mitigation measures (Navarro et al. 2020). In Bangladesh, massive public protests were observed against the establishment of quarantine services (Bodrud-Doza et al. 2020), and dengue cases have already increased by fourfold this year as compared to the previous years (Rahman et al. 2020).

The spirit of oneness and solidarity that characterizes the COVID-19 response in Bhutan and elsewhere should be emulated for dengue and other infectious disease threats. We are not recommending lockdowns in response to dengue epidemics, but rather a collective responsibility of society, focusing on high levels of compliance with government regulations and community participation, including volunteering to control dengue vector mosquitoes, as demonstrated in the combat against COVID-19. Tackling dengue is every citizen’s responsibility and it should not be left to the Ministry of Health alone. Dengue is a cross-cutting issue covering health and several other ministries, agencies, non-government and civil society organizations and communities. To emphasize this point, in several other countries, dengue control programs are organized by the Ministry of Environment rather than the Ministry of Health (World Health Organization 2012). Dengue prevention and control need a more participatory approach and better use of the existing network of partnerships and collaborations. Social mobilization and collaboration with organizations outside the health sector and local communities are crucial for the successful implementation of integrated vector management. Similar to COVID-19, every individual has the responsibility to contribute to the national response to the threat of dengue to achieve better health outcomes for all.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References Cited

- Bansal N, Bansal Y, and Ralta A. . 2020. Thrombocytopenia in COVID-19 patients in Himachal Pradesh (India) and the absence of dengue false-positive tests: insights for patient management. J. Med. Virol. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodrud-Doza M, Shammi M, Bahlman L, Islam A R M T, and Rahman M M. . 2020. Psychosocial and socio-economic crisis in Bangladesh due to COVID-19 pandemic: a perception-based assessment. Front. Public Health 8: 341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020. Dengue and COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/is-it-dengue-or-covid.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, . et al. 2020. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 395: 507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantés H G, Manrique-Saide P, Vazquez-Prokopec G, Morales F C, Siqueira Junior J B, Pimenta F, Coelho G, and Bezerra H. . 2020. Prevention and control of Aedes transmitted infections in the post-pandemic scenario of COVID-19: challenges and opportunities for the region of the Americas. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 115: e200284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrina J, Putra I C S, Lawrensia S, Handoyono Q F, and Cahyadi A. . 2020. Coronavirus disease of 2019: a mimicker of Dengue infection? SN Compr Clin Med. 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00364-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joob B, and Wiwanitkit V. . 2020. COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for dengue. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 82: e177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kembuan G J. 2020. Dengue serology in Indonesian COVID-19 patients: coinfection or serological overlap? Idcases. 22: e00927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball A, Hatfield K M, Arons M, James A, Taylor J, Spicer K, Bardossy A C, Oakley L P, Tanwar S, Chisty Z, . et al. ; Public Health – Seattle & King County; CDC COVID-19 Investigation Team. 2020. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in residents of a long-term care skilled nursing facility - King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhaes T, Chalegre K D M, Braga C, and Foy B D. . 2020. The endless challenges of arboviral diseases in Brazil. Trop Med Infect Dis. 5: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas M D M, Batista F M A, Rodrigues M T P, Barbosa O A A, and Barros V C. . 2020. Simultaneous occurrence of COVID-19 and dengue: what do the data show? Cad. Saude Publica. 36: e00126520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro J C, Arrivillaga-Henríquez J, Salazar-Loor J, and Rodriguez-Morales A J. . 2020. COVID-19 and dengue, co-epidemics in Ecuador and other countries in Latin America: pushing strained health care systems over the edge. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 101656. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasitsirikul W, Pongpirul K, Pongpirul W A, Panitantum N, Ratnarathon A C, and Hemachudha T. . 2020. Nurse infected with Covid-19 from a provisional dengue patient. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9: 1354–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M T, Sobur M A, Islam M S, Toniolo A, and Nazir K H M N H. . 2020. Is the COVID-19 pandemic masking dengue epidemic in Bangladesh? J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 7: 218–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott T W, and Morrison A C. . 2010. Vector dynamics and transmission of dengue virus: implications for dengue surveillance and prevention strategies: vector dynamics and dengue prevention. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 338: 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsheten T, Clements A C A, Gray D J, Wangchuk S, and Wangdi K. . 2020. Spatial and temporal patterns of dengue incidence in Bhutan: a Bayesian analysis. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9: 1360–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduyn M, Allou N, Gazaille V, Andre M, Desroche T, Jaffar M C, Traversier N, Levin C, Lagrange-Xelot M, Moiton M P, . et al. 2020. Co-infection of dengue and COVID-19: a case report. Plos Negl. Trop. Dis. 14: e0008476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization 2009. Dengue guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control: New Edition. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization 2012. Global strategy for dengue prevention and control, 2012–2020. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): weekly epidemiological update, August 24, 2020. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Yan G, Lee C K, Lam L T M, Yan B, Chua Y X, Lim A Y N, Phang K F, Kew G S, Teng H, Ngai C H, . et al. 2020. Covert COVID-19 and false-positive dengue serology in Singapore. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 20: 536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]