Abstract

Background

We aimed to examine the impact of lockdown on sexually transmitted infection (STI) diagnoses and access to a public sexual health service during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Melbourne, Australia.

Methods

The operating hours of Melbourne Sexual Health Centre (MSHC) remained the same during the lockdown. We examined the number of consultations and STIs at MSHC between January and June 2020 and stratified the data into prelockdown (February 3 to March 22), lockdown (March 23 to May 10), and postlockdown (May 11 to June 28), with 7 weeks in each period. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using Poisson regression models.

Results

The total number of consultations dropped from 7818 in prelockdown to 4652 during lockdown (IRR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.57–0.62) but increased to 5347 in the postlockdown period (IRR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.11–1.20). There was a 68% reduction in asymptomatic screening during lockdown (IRR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.30–0.35), but it gradually increased during the postlockdown period (IRR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.46–1.74). Conditions with milder symptoms showed a marked reduction, including nongonococcal urethritis (IRR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.51–0.72) and candidiasis (IRR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.49–0.76), during lockdown compared with prelockdown. STIs with more marked symptoms did not change significantly, including pelvic inflammatory disease (IRR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.61–1.47) and infectious syphilis (IRR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.73–1.77). There was no significant change in STI diagnoses during postlockdown compared with lockdown.

Conclusions

The public appeared to be prioritizing their attendance for sexual health services based on the urgency of their clinical conditions. This suggests that the effectiveness of clinical services in detecting, treating, and preventing onward transmission of important symptomatic conditions is being mainly preserved despite large falls in absolute numbers of attendees.

Keywords: Australia, coronavirus, COVID, health service, sexual health, sexually transmitted infections

Cases of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) began gradually increasing in Australia after the first case was identified on January 25, 2020. In response, the Australian government initially closed its international borders to all nonresidents on March 20 and followed with different stages of restriction and lockdown. The national Stage 1 restriction was introduced on midday March 23, which included the closure of nonessential businesses, restriction on social gatherings, and social distancing rules [1]. Australia moved to Stage 2 restriction from 11:59 pm on March 25, with further restrictions on indoor and outdoor social gatherings limited to 2 persons only, and also introduced mandatory quarantine for 14 days after international travel on March 28 [1]. Further, Victoria moved to Stage 3 restriction from 11:59 pm on March 30 by introducing the “stay at home” directions where Victorians could only leave home for 4 reasons (ie, medical needs; work or study; exercising; or shop for food and essential supplies). During the lockdown in March–April in Melbourne, there were no reductions or restrictions on public transportation. In Victoria, restrictions began to ease from 11:59 pm on May 12 onwards and included allowing family and friends to visit homes.

Several studies have provided evidence demonstrating that there was a reduction in casual sex during lockdown [2–6]; this is also supported by the evidence of reduction in HIV postexposure prophylaxis during lockdown in several countries [7–9]. Hence, it is reasonably hypothesized that these changes are likely to have translated into a reduction in sexually transmitted infections (STIs). However, there has been very limited research examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on STIs. We aimed to examine the patterns and changes of STI diagnoses and access to sexual health services before and after lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic in Melbourne, Australia.

METHODS

This study was conducted at the Melbourne Sexual Health Centre (MSHC) between January and June 2020. MSHC is the largest public sexual health service in Victoria in Australi; it provided ~50 000 consultations annually between 2017 and 2019 (with an average quarterly number of consultations of 13 000 in the first quarter and 12 000 in the second, third, and fourth quarters), but the total number of consultations did not vary substantially across seasons at MSHC [10]. All consultations, HIV/STI testing, and treatment are free of charge for all individuals. MSHC remained open during the lockdown period. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was no change in medical staff, but up to 25% of the nursing staff were moved to COVID-19 duties elsewhere (eg, contact tracing for COVID-19). However, this did not change any clinic practices or processes, as the clinic was quiet and underutilized during lockdown. MSHC operates a walk-in service for individuals with symptoms and for urgent matters, but individuals who did not have any symptoms were required to call the clinic for an appointment for a face-to-face visit; this remained unchanged before and after the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our on-site lab was still operating as usual during the lockdown period, and there were no changes in the services in relation to testing and sample collection other than MSHC moved from clinician-collected to self-collected throat swabs [11]. MSHC did not offer any off-site or home testing throughout the period. Upon arrival, all clients were first screened for flu-like symptoms and had their temperature taken. Individuals were asked not to attend the clinic if they (1) were waiting for the testing result of a COVID-19 test; (2) tested positive for COVID-19; (3) were required to be self-isolated due to COVID-19; or (4) had symptoms of COVID-19. The same rules applied to all staff at MSHC. Individuals with symptoms of COVID-19 were not seen at MSHC and were sent to the hospital for COVID-19 testing. Phone consultations were provided to stable patients with HIV in a dedicated HIV clinic that is not part of this analysis but not to other patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Consultations data were extracted from the electronic medical record at MSHC and were stratified by sex (males, females, or others). “Other” sex was defined as individuals who self-reported their sex as intersex, transgender, or other. Data included the type of consultation (eg, asymptomatic screening vs symptomatic/urgent), reasons for attendance (eg, reporting as a contact of infection, requesting a sex work certificate), diagnoses of STI or genital infections, number of sex partners in the preceding 3 months, and the time between symptom onset to clinic attendance. We were interested in STI or genital infections among 4 different client groups—(i) those presenting for an “asymptomatic screen,” defined as individuals who did not have any symptoms, attended the clinic for on-site lab-based testing for HIV/STI, and did not require a physical examination; (ii) those presenting as “symptomatic/urgent cases,” defined as those presenting with symptoms related to STI (eg, genital discharge, genital ulcer, and pelvic pain) and/or those requiring urgent attention (eg, accessing postexposure prophylaxis); (iii) those presenting as a “contact of infection,” defined as individuals reporting contact with sex partners with an STI (including gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and Mycoplasma genitalium); and (iv) those requesting a “sex work certificate,” defined as individuals working in the sex work industry who required an in-date certificate as evidence of 3-monthly HIV/STI screening (a legal requirement for anyone doing sex work in Victoria) [12]. Eight common symptomatic STIs or genital infections were selected as the outcomes in this study; these included balanitis, bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, herpes (initial episodes or recurrent infections), infectious syphilis (primary or secondary syphilis), nongonococcal urethritis (NGU), pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and urethral gonorrhea. We did not look at asymptomatic conditions such as chlamydia and HIV because these conditions mainly relied on the frequency of asymptomatic screening, which might be biased due to the COVID-19 pandemic or lockdown period.

The number of consultations and the diagnoses of STI or genital infections were summed across each week and plotted by calendar week starting from the week commencing on January 6 (Monday) to the week ending on June 28 (Sunday), stratified by the sex of the individuals. MSHC closes on public holidays, and therefore the weekly number of consultations is biased if the public holiday occurs on a weekday; hence, we adjusted the number of consultations by multiplying the weekly number by 5/n, where n is the number of working days, and we present both the crude number and the adjusted number of weekly consultations [13]. For “asymptomatic screen” in males, we further stratified into either (1) men who have sex with men (MSM); or (2) males who had had sex with females only (MSW). This is because 3-monthly HIV/STI screening is recommended for all sexually active MSM but not heterosexuals. We further stratified the study period into 3 periods of 7 weeks: (1) prelockdown (February 3 to March 22); (2) lockdown (March 23 to May 10); and (3) postlockdown (May 11 to June 28). Poisson regression models were used for the count data for the number of consultations and the diagnoses of STI or genital infections, and the Poisson regression coefficients were calculated. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated by exponentiating the Poisson regression coefficients, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were also calculated. We reported the IRR in the lockdown period compared with the prelockdown period and in the postlockdown period compared with the lockdown period. We reported the mean number of sex partners, and the regression coefficient (beta) was calculated from linear regression to determine whether there was any change (increase, decrease, or no change) in the 3 time periods (prelockdown, during lockdown, and postlockdown). The mean time between symptom onset and clinic attendance was also calculated. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata (version 14; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). This study was approved by the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee, Melbourne, Australia (301/20).

RESULTS

Total Number of Clinical Consultations

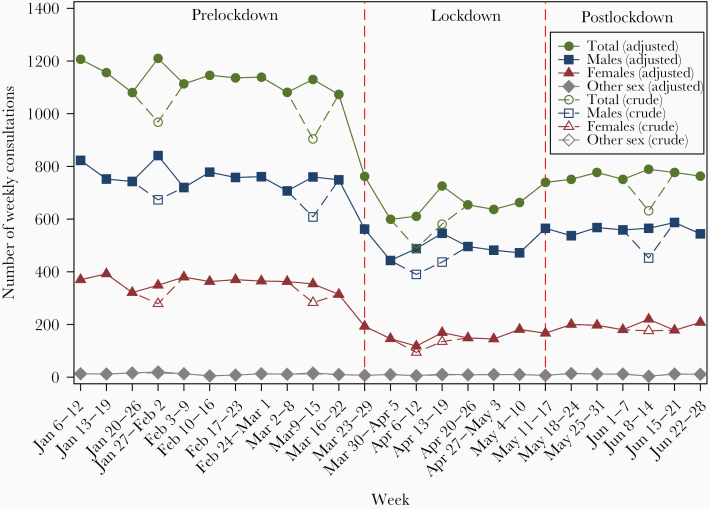

There were 21 576 clinical consultations between January 6, 2020, and June 26, 2020. There were about 1100 consultations each week before lockdown, which dropped dramatically in the weeks after the lockdown on March 23, 2020, to a low of 600 consultations per week (Figure 1). The total number of consultations began to rise after 3 weeks of lockdown, reaching about 800 consultations each week in May–June, but the weekly number of consultations was still lower compared with the level before lockdown. Compared with prelockdown period, there was a 40% reduction (IRR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.57–0.62) in the total number of consultations during lockdown; however, there was an increase in the number of consultations in the postlockdown period (IRR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.11–1.20), but the number was still lower compared with prelockdown (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The number of crude and adjusted weekly consultations between January 6 and June 28, 2020, stratified by sex. The crude weekly consultations represent the actual number of weekly consultations, while the adjusted weekly consultations were calculated by multiplying the crude weekly number by 5/n, where n is the number of working days, to minimize the bias of public holiday effects.

Table 1.

The Number of Clinical Consultations and STI Diagnoses, Stratified by Lockdown Periods and Population

| 7 Weeks Prelockdown | 7 Weeks During Lockdown | IRR (95% CI), Comparing During Lockdown With Prelockdown | P Value | 7 Weeks Postlockdown | IRR (95% CI), Comparing Postlockdown With During Lockdown | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of consultations | |||||||

| Total consultations (adjusted)a | |||||||

| All | 7818 | 4652 | 0.60 (0.57–0.62) | <.001 | 5347 | 1.15 (1.11–1.20) | <.001 |

| Males | 5233 | 3489 | 0.67 (0.64–0.70) | <.001 | 3925 | 1.12 (1.07–1.18) | <.001 |

| Females | 2509 | 1101 | 0.44 (0.41–0.47) | <.001 | 1350 | 1.23 (1.13–1.33) | <.001 |

| Others | 76 | 63 | 0.83 (0.59–1.16) | .271 | 72 | 1.14 (0.81–1.60) | .439 |

| Asymptomatic screenb | |||||||

| All | 2425 | 788 | 0.32 (0.30–0.35) | <.001 | 1254 | 1.59 (1.46–1.74) | <.001 |

| Males | 1482 | 579 | 0.39 (0.35–0.43) | <.001 | 875 | 1.51 (1.36–1.68) | <.001 |

| Men who have sex with men | 943 | 399 | 0.42 (0.38–0.48) | <.001 | 584 | 1.46 (1.29–1.66) | <.001 |

| Men who have sex with women only | 539 | 180 | 0.33 (0.28–0.40) | <.001 | 291 | 1.62 (1.34–1.95) | <.001 |

| Females | 914 | 200 | 0.22 (0.19–0.25) | <.001 | 356 | 1.78 (1.50–2.12) | <.001 |

| Others | 29 | 9 | 0.31 (0.15–0.66) | .002 | 23 | 2.56 (1.18–5.52) | .017 |

| Symptomatic/urgent casesc | |||||||

| All | 2527 | 1502 | 0.59 (0.56–0.63) | <.001 | 1880 | 1.25 (1.17–1.34) | <.001 |

| Males | 1648 | 1022 | 0.62 (0.57–0.67) | <.001 | 1291 | 1.26 (1.16–1.37) | <.001 |

| Females | 858 | 466 | 0.54 (0.49–0.61) | <.001 | 575 | 1.23 (1.09–1.39) | <.001 |

| Others | 21 | 14 | 0.67 (0.34–1.31) | .240 | 14 | 1.00 (0.48–2.10) | 1.000 |

| Attending for a sex work certificated | |||||||

| All | 94 | 9 | 0.10 (0.05–0.19) | <.001 | 11 | 1.22 (0.51–2.95) | .655 |

| Males | 1 | 1 | 1.00 (0.06–15.99) | 1.000 | 1 | 1.00 (0.06–15.99) | 1.000 |

| Females | 93 | 8 | 0.09 (0.04–0.18) | <.001 | 9 | 1.13 (0.43–2.92) | .808 |

| Others | 0 | 0 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Contact of infectionse | |||||||

| All | 527 | 344 | 0.65 (0.57–0.75) | <.001 | 468 | 1.36 (1.18–1.56) | <.001 |

| Males | 427 | 299 | 0.70 (0.60–0.81) | <.001 | 380 | 1.27 (1.09–1.48) | .002 |

| Females | 96 | 43 | 0.45 (0.31–0.64) | <.001 | 83 | 1.93 (1.34–2.79) | <.001 |

| Others | 4 | 2 | 0.50 (0.09–2.73) | .423 | 5 | 2.50 (0.49–12.89) | .273 |

| STI diagnoses | |||||||

| Balanitis | |||||||

| All | 116 | 64 | 0.55 (0.41–0.75) | <.001 | 82 | 1.28 (0.92–1.78) | .137 |

| Males | 116 | 64 | 0.55 (0.41–0.75) | <.001 | 81 | 1.27 (0.91–1.76) | .159 |

| Females | N/A | N/A | - | - | N/A | - | - |

| Others | 0 | 0 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Bacterial vaginosis | |||||||

| All | 237 | 129 | 0.54 (0.44–0.67) | <.001 | 160 | 1.24 (0.98–1.56) | .069 |

| Males | N/A | N/A | - | - | N/A | - | - |

| Females | 237 | 128 | 0.54 (0.44–0.67) | <.001 | 159 | 1.24 (0.98–1.57) | .068 |

| Others | 0 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1.00 (0.06–15.99) | 1.000 |

| Candidiasis | |||||||

| All | 211 | 129 | 0.61 (0.49–0.76) | <.001 | 129 | 1.00 (0.78–1.28) | 1.000 |

| Males | 3 | 2 | 0.67 (0.11–3.99) | .657 | 0 | - | - |

| Females | 206 | 127 | 0.62 (0.49–0.77) | <.011 | 129 | 1.02 (0.80–1.30) | .901 |

| Others | 2 | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

| Herpes | |||||||

| All | 127 | 61 | 0.48 (0.35–0.65) | <.001 | 72 | 1.18 (0.84–1.66) | .341 |

| Males | 82 | 37 | 0.45 (0.31–0.67) | <.001 | 44 | 1.19 (0.77–1.84) | .437 |

| Females | 44 | 22 | 0.50 (0.30–0.83) | .008 | 27 | 1.23 (0.70–2.15) | .476 |

| Others | 1 | 2 | 2.00 (0.18–22.06) | .571 | 1 | 0.50 (0.05–5.51) | .571 |

| Herpes (initial episode) | |||||||

| All | 83 | 34 | 0.41 (0.27–0.61) | <.001 | 42 | 1.24 (0.79–1.94) | .360 |

| Males | 56 | 19 | 0.34 (0.20–0.57) | <.001 | 24 | 1.26 (0.69–2.31) | .447 |

| Females | 26 | 15 | 0.58 (0.31–1.09) | .090 | 18 | 1.20 (0.60–2.38) | .602 |

| Others | 1 | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

| Herpes (recurrent infection) | |||||||

| All | 27 | 19 | 0.70 (0.39–1.27) | .241 | 18 | 0.95 (0.50–1.81) | .869 |

| Males | 16 | 13 | 0.81 (0.39–1.69) | .578 | 12 | 0.92 (0.42–2.02) | .842 |

| Females | 11 | 4 | 0.36 (0.12–1.14) | .083 | 5 | 1.25 (0.34–4.65) | .739 |

| Others | 0 | 2 | - | - | 1 | 0.50 (0.05–5.51) | .571 |

| Infectious syphilis (primary or secondary) | |||||||

| All | 37 | 42 | 1.14 (0.73–1.77) | .574 | 27 | 0.64 (0.40–1.04) | .073 |

| Males | 34 | 38 | 1.12 (0.70–1.78) | .638 | 27 | 0.71 (0.43–1.16) | .175 |

| Females | 2 | 3 | 1.50 (0.25–8.98) | .657 | 0 | - | - |

| Others | 1 | 1 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

| Infectious syphilis (primary) | |||||||

| All | 28 | 24 | 0.86 (0.50–1.48) | .579 | 16 | 0.67 (0.35–1.25) | .209 |

| Males | 27 | 22 | 0.81 (0.46–1.43) | .476 | 16 | 0.73 (0.38–1.38) | .332 |

| Females | 1 | 1 | 1.00 (0.06–15.99) | 1.000 | 0 | - | - |

| Others | 0 | 1 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

| Infectious syphilis (secondary) | |||||||

| All | 9 | 18 | 2.00 (0.90–4.45) | .090 | 11 | 0.61 (0.29–1.29) | .198 |

| Males | 7 | 16 | 2.29 (0.94–5.56) | .068 | 11 | 0.69 (0.32–1.48) | .339 |

| Females | 1 | 2 | 2.00 (0.18–22.06) | .571 | 0 | - | - |

| Others | 1 | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

| Nongonococcal urethritis | |||||||

| All | 349 | 211 | 0.60 (0.51–0.72) | <.001 | 245 | 1.16 (0.97–1.40) | .112 |

| Males | 348 | 208 | 0.60 (0.50–0.71) | <.001 | 243 | 1.17 (0.97–1.41) | .100 |

| Females | 0 | 1 | - | - | 2 | 2.00 (0.18–22.06) | .571 |

| Others | 1 | 2 | 2.00 (0.18–22.06) | .571 | 0 | - | - |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | |||||||

| All | 41 | 39 | 0.95 (0.61–1.47) | .823 | 30 | 0.77 (0.48–1.24) | .280 |

| Males | N/A | N/A | - | - | N/A | - | - |

| Females | 41 | 38 | 0.93 (0.60–1.44) | .736 | 30 | 0.79 (0.49–1.27) | .333 |

| Others | 0 | 1 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

| Urethral gonorrhea | |||||||

| All | 95 | 52 | 0.55 (0.39–0.77) | <.001 | 56 | 1.08 (0.74–1.57) | .700 |

| Males | 90 | 51 | 0.57 (0.40–0.80) | .001 | 54 | 1.06 (1.06–0.72) | .770 |

| Females | 4 | 1 | 0.25 (0.03–2.24) | .215 | 1 | 1.00 (0.06–15.99) | 1.000 |

| Others | 1 | 0 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

Abbreviations: IRR, incidence rate ratio; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

aThe total number of consultations was adjusted by multiplying the weekly number by 5/n, where n is the number of working days, to minimize the bias of public holiday effects.

bAsymptomatic screen was defined as individuals who did not have any symptoms and attended the clinic for HIV/STI screening.

cSymptomatic/urgent case was defined as individuals presented with symptoms related to STI (eg, genital discharge, genital ulcer, and pelvic pain) and/or those requiring urgent attention (eg, accessing postexposure prophylaxis).

dA “sex work certificate” was defined as individuals working in the sex work industry requiring an in-date certificate as evidence of 3-monthly HIV/STI screening (a legal requirement for anyone doing sex work in Victoria).

eContact of infection was defined as individuals reporting contact with sex partners with an STI (including gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and Mycoplasma genitalium).

Reasons for Attendance

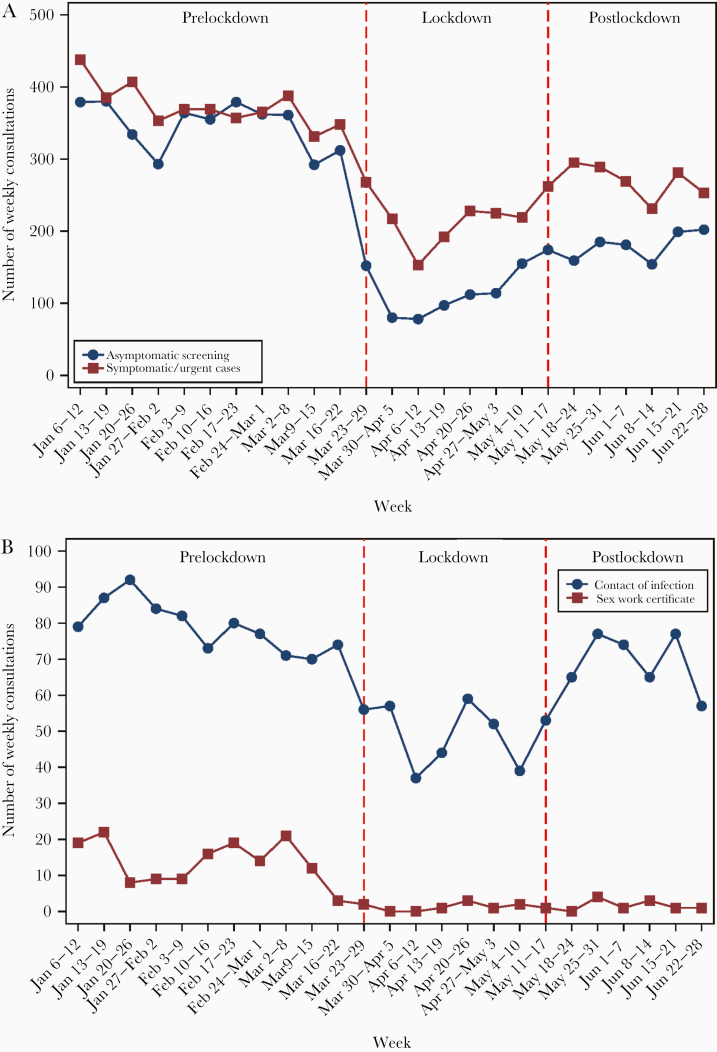

There was a 68% reduction (IRR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.30–0.35) in the number of consultations for asymptomatic screening during lockdown compared with prelockdown, with a 78% reduction (IRR, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.19–0.25) in females, followed by a 67% reduction (IRR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.28–0.40) in MSW, then a 58% reduction (IRR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.38–0.48) in MSM (Table 1). However, there was an increase in the number of consultations for asymptomatic screening in the postlockdown period (IRR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.46–1.76) (Table 1), with about 150–200 consultations each week in May–June, and this number was still lower compared with prelockdown (about 350 consultations each week) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The number of weekly consultations, stratified by (A) asymptomatic screening and urgent cases; and (B) clients who self-reported as a contact of infection and attending for a sex work certificate, between January 6 and June 28, 2020.

Furthermore, there was a 35% reduction (IRR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.57–0.75) in the number of consultations for people reporting as a contact of infection during lockdown (Table 1), with a nadir of 37 in the third week of lockdown, but the number began to rise in May and returned to the level before lockdown (Figure 2). There was also a marked decline in females attending the clinic for a sex work certificate during lockdown, a 91% reduction (IRR, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.04–0.18) (Table 1, Figure 2).

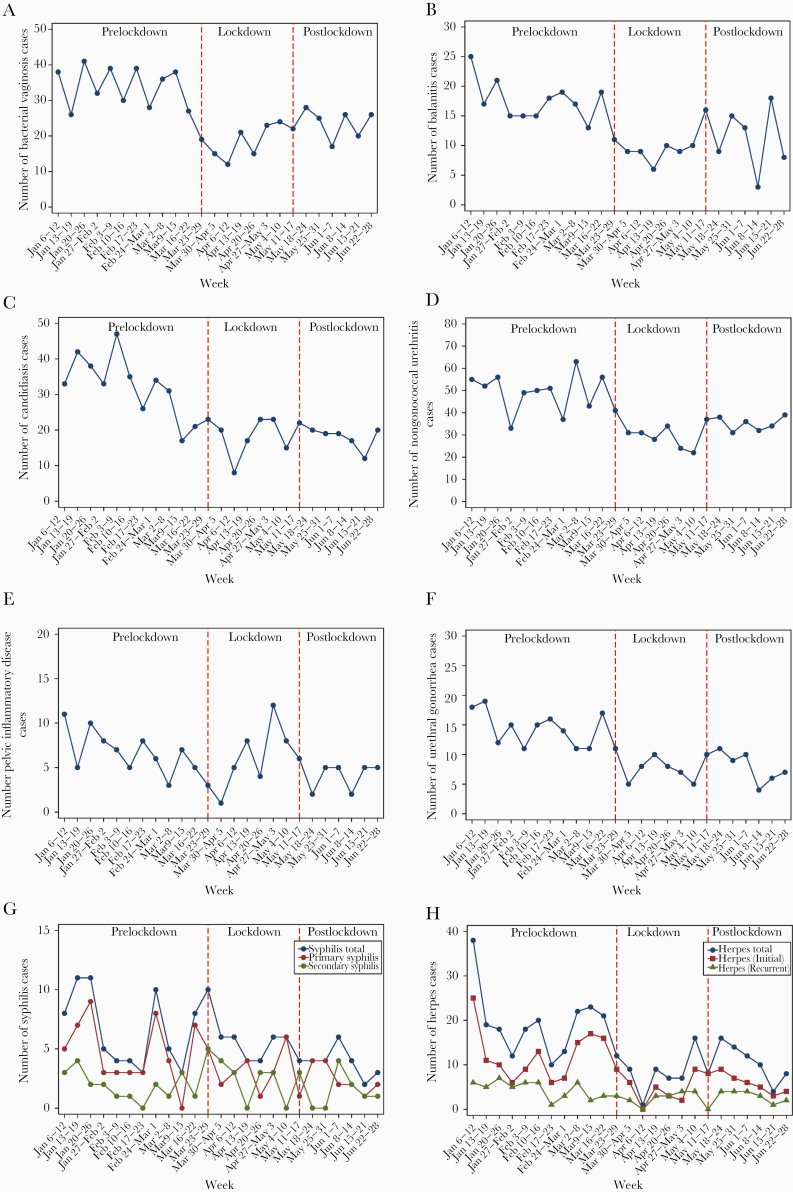

Changes in STI and Genital Infections

There was a 41% reduction in the number of symptomatic/urgent cases (IRR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.56–0.63) in the lockdown period compared with prelockdown, although this was lower than was seen for asymptomatic screening. Symptomatic presentations with more mild symptoms showed a marked reduction, a 45% reduction (IRR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.41–0.75) in balanitis in males, a 46% reduction (IRR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44–0.67) in bacterial vaginosis in females, a 40% reduction (IRR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50–0.71) in NGU in males, and a 38% reduction (IRR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.49–0.77) in candidiasis in females. There was also a significant reduction in conditions with short incubation period; this included a 45% reduction in urethral gonorrhea (IRR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.39–0.77) and a 59% reduction in initial herpes (IRR, 0.41; 95% CI, 27–0.61). However, conditions with more marked symptoms showed a nonsignificant change in the lockdown period: This included PID (IRR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.61–1.47) and infectious syphilis (IRR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.73–1.77). There was no significant change in all STI diagnoses or genital infections in postlockdown compared with during the lockdown period (Table 1, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The weekly number of the diagnoses of (A) bacterial vaginosis; (B) balanitis; (C) candidiasis; (D) nongonoccocal urethritis; (E) pelvic inflammatory diseases; (F) urethral gonorrhea; (G) syphilis; and (H) herpes, between January 6 and June 28, 2020.

Access to Health Care Service Among Symptomatic Individuals

Among those who presented with symptoms and reported the number of days of symptoms, the mean number of days between symptom onset and clinic attendance in lockdown (31.7 [95% CI, 25.2–38.3] days) did not differ compared with prelockdown (28.0 [95% CI, 23.8–32.2] days; P = .330) or postlockdown (37.3 [95% CI, 31.0–43.5] days; P = .231), while the median number of days between symptom onset and clinic attendance was 7 days for all 3 periods.

Changes in the Number of Sex Partners in the Preceding 3 Months

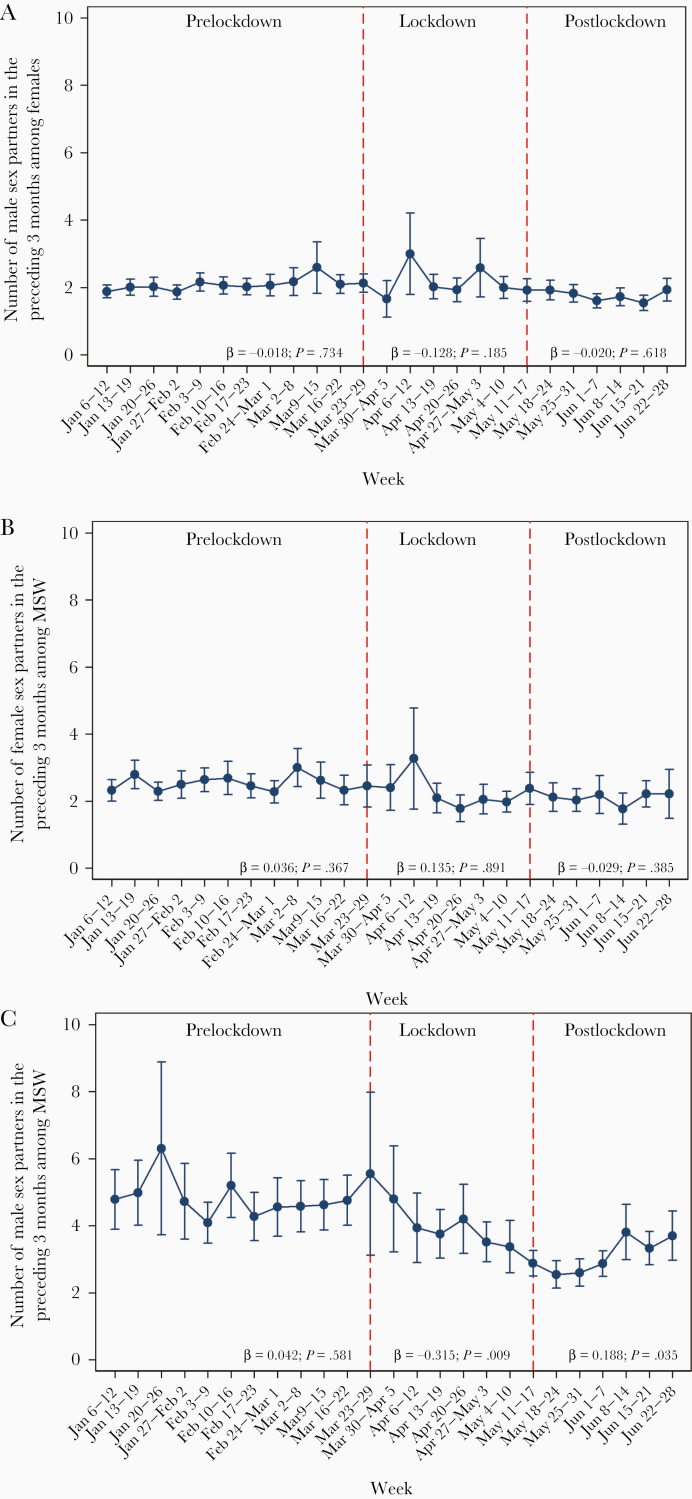

The number of sex partners in the preceding 3 months among MSM did not change in the prelockdown period (β = 0.042; P = .581), with an overall mean (SD) of 4.6 (6.6) men, and the mean number of sex partners declined in the lockdown period (β = –0.315; P = .009), with an overall mean (SD) of 4.2 (8.6) men, but it started to increase in the postlockdown period (β = 0.188; P = .035), with an overall mean (SD) of 3.1 (3.5) men in postlockdown. However, there was no change in the mean number (SD) of sex partners in the preceding 3 months among females (2.2 [2.9], 2.1 [2.5], 1.8 [1.6]) and MSW (2.6 [2.8], 2.2 [2.6], 2.1 [2.5]) during the prelockdown, lockdown, and postlockdown periods, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mean number of sex partners in the preceding 3 months, stratified by calendar week, among (A) females; (B) men who have sex with women only (MSW); and (C) men who have sex with men (MSM). Beta coefficient from the linear regression and its P value were presented for the prelockdown (February 3 to March 22), lockdown (March 23 to May 10), and postlockdown (May 11 to June 28) periods. A positive beta coefficient represents an increasing trend in the number of partners, while a negative beta-coefficient represents a decreasing trend in the number of partners.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on STI diagnoses and access to sexual health services during lockdown in Australia and one of few internationally. We found dramatic reductions in attendance particularly for low-risk reasons such as asymptomatic screening. There were less marked reductions for symptomatic individuals and no significant reductions among some more symptomatic and important clinical conditions such as pelvic inflammatory disease or syphilis. Interestingly, attendance for asymptomatic screening rose quickly in the postlockdown period, but no significant increases were seen for symptomatic conditions, suggesting possibly that the lockdown may have also caused a reduction in the incidence of these conditions in addition to discouraging attendance to our clinical service. The number of sex partners almost halved among MSM during the study period, with some suggestion of a recovery in the postlockdown period, a finding that is consistent with the failure of STI diagnoses to rise in the postlockdown period despite marked rises in asymptomatic screening. Given the important contribution that clinical services make to STI control, it may be that a public health campaign is needed to encourage screening of those at risk, and more importantly to encourage symptomatic individuals to seek health care promptly.

The reduction in asymptomatic screening at the beginning of lockdown is not unexpected, as all health services including cancer screening programs have reported reductions in attendance [14]. However, some reductions may also be explained by changes in sexual practices during the lockdown [4]. An Australian online survey conducted in April–May 2020 revealed that Australians reported fewer casual hook-ups during lockdown (8%) compared with 2019 (31%) [3]. In August 2020, the Terrence Higgins Trust in the United Kingdom recommended some safe sex practices during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as stopping kissing, wearing a face mask during sex, and changing sexual positions so that there is no face-to-face contact [15], although it is not clear how widely these recommendations have been adopted. Further studies will be required to examine whether individuals have changed their practices as per these recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Another explanation of the reduction in asymptomatic screening could be due to the fear of catching COVID-19 when visiting clinics [2], and individuals might have delayed their regular HIV/STI screening. Our data has also shown that the number of asymptomatic screenings gradually increased in the postlockdown period; this is either because the COVID-19 epidemic in Melbourne began to be under control in May–June or because individuals began to resume having sex. This increase in presentations fits with a similar pattern seen among individuals reporting as a contact of infection.

We also observed that there was a significant reduction in the number of sex work certificates issued. This is likely to due to the closure of brothels in Victoria since March 2020 and there being no need for sex workers to obtain certificates, which are required under Victorian law to work in brothels. Some sex workers might have changed their services from in-person to virtual (eg, webcamming and phone sex) [16]. Sex workers in Victoria have low HIV/STI prevalence, and hence they do not drive STI rates in Victoria [17, 18]. A previous study showed that sex workers acquire most STIs from their nonpaying private partners, not from their clients [19]. Further research is needed to examine the impact COVID-19 restrictions have had on sex workers in Victoria.

There was a marked reduction in most but not all STI or genital infections. Milder conditions (eg, bacterial vaginosis, balanitis) had moderate reductions of about 45%, but some conditions (eg, infectious syphilis, PID) did not reduce virtually at all despite large reductions in other conditions. It is not possible to determine why this difference occurred; however, one could postulate that the seriousness or nature of the symptoms contributed to the continued attendance for some conditions. The failure to see a resurgence in all STI diagnoses may in part relate to a reduction in the incidence of some conditions, a finding that is consistent with the reduction in the number of sex partners observed in some groups.

There are limited studies examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on STIs, and we can only identify 2 similar studies. Latini and colleagues reported that even though there was a 3-fold rise of syphilis cases in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the same period in 2019 (68 vs 25 cases) in Rome, only 15 cases were diagnosed in March 2020, and all of these were during the first week of March [20]. Cusini and colleagues reported the number of HIV/STI diagnoses in Italy between March 15, 2020, and April 14, 2020 (during lockdown), and compared it with the same period in 2019 [21]; they concluded that there was a reduction in nonacute conditions (eg, warts [72 cases in 2019 vs 18 cases in 2020] and molluscum [18 cases in 2019 vs 2 cases in 2020]), but this was not the case for acute conditions (eg, secondary syphilis [30 cases in 2019 vs 33 cases in 2020]), which is consistent with our findings.

There are several limitations to this study. First, this study was conducted in one urban sexual health clinic in Melbourne. Our findings may not be generalizable to other Australian states or countries due to the different levels of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures. Second, some individuals were worried about catching COVID-19 when visiting clinics and might have delayed seeking health care during the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. Although the time from symptom onset to clinic attendance did not differ before and after lockdown in our study, we were unable to stratify these data by different STI diagnoses due to the small sample size, as not all individuals reported the number of days with symptoms. Third, we collected the number of sex partners 3 months preceding the date of attendance, and therefore it might have underestimated the impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on sexual practices. In addition, we only collected the number of sex partners, and this may not represent the frequency of sexual encounters over the period, which is an important factor for STI transmission. Fourth, we were unable to compare the STI diagnoses at our clinic with state-wide or nation-wide surveillance data, as most of these conditions were not notifiable in Australia.

By the end of June, the COVID-19 epidemic in most Australian states and territories was under control, except for Victoria [22]. The number of daily COVID-19 cases began to rise in late June in Victoria and peaked at 700 cases reported on August 5 [23]. Victoria recorded a total of 12 600 cases (66% of the cases in Australia) by the end of July [24]. From 11:59 pm July 1, 2020, Stage 3 restrictions were applied to 10 postcodes in Victoria, and the restrictions further expanded to metropolitan Melbourne and Mitchell Shire on July 8, 2020, as well as the introduction of compulsory face masks in public on July 22, 2020. From 6 pm on August 2, 2020, Stage 4 restrictions (including a curfew between 8 pm and 5 am) were applied to metropolitan Melbourne and Mitchell Shire, and Stage 3 restrictions were applied to regional Victoria. All sex work is banned under stage 3 and 4 restrictions. Further studies will be required to examine the impact of these new restrictions during lockdown on STIs and to potentially compare the STI rate with other Australian states where restrictions are eased.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Afrizal Afrizal at the Melbourne Sexual Health Centre for his assistance in extracting the data.

Financial support. E.P.F.C. and C.K.F. are each supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator Grant (GNT1172873 for E.P.F.C. and GNT1172900 for C.K.F.). J.J.O. is supported by an NHRMC Early Career Fellowship (GNT1104781). J.S.H. is supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (GNT1136117).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Author contributions. E.P.F.C. and C.K.F. conceived and designed the study. J.S.H. and J.J.O. assisted with the study design. E.P.F.C. oversaw the study, prepared the ethics application, performed data analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in data interpretation and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Patient consent. Informed consent was not required because this was an analysis of retrospective clinical data. This study was approved by the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee, Melbourne, Australia (301/20).

References

- 1. COVID-19 National Incident Room Surveillance Team. COVID-19, Australia: epidemiology report 20 (fortnightly reporting period ending 5 July 2020) Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2020; 44. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chow EPF, Hocking JS, Ong JJ, et al. Changing the use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men during the COVID-19 pandemic in Melbourne, Australia. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:ofaa275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coombe J, Kong FYS, Bittleston H, et al. Love during lockdown: findings from an online survey examining the impact of COVID-19 on the sexual practices of people living in Australia [published online ahead of print November 17, 2020]. Sex Transm Infect 2020. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hammoud MA, Maher L, Holt M, et al. Physical distancing due to COVID-19 disrupts sexual behaviours among gay and bisexual men in Australia: Implications for trends in HIV and other sexually transmissible infections. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020; 85:309–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Sousa AFL, Oliveira LB, Schneider G, et al. Casual sex among MSM during the period of social isolation in the COVID-19 pandemic: nationwide study in Brazil and Portugal. medRxiv 2020.06.07.20113142 [Preprint]. 23 September 2020. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.07.20113142. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanchez TH, Zlotorzynska M, Rai M, Baral SD. Characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on men who have sex with men across the United States in April, 2020. AIDS Behav 2020; 24:2024–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chow EPF, Hocking JS, Ong JJ, et al. Postexposure prophylaxis during COVID-19 lockdown in Melbourne, Australia. Lancet HIV 2020; 7:e528–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Junejo M, Girometti N, McOwan A, Whitlock G; Dean Street Collaborative Group HIV postexposure prophylaxis during COVID-19. Lancet HIV 2020; 7:e460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sanchez-Rubio J, Velez-Diaz-Pallares M, Rodriguez Gonzalez C, et al. HIV postexposure prophylaxis during the COVID-19 pandemic: experience from Madrid [published online ahead of print July 17, 2020]. Sex Transm Infect 2020. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cornelisse VJ, Chow EP, Chen MY, et al. Summer heat: a cross-sectional analysis of seasonal differences in sexual behaviour and sexually transmissible diseases in Melbourne, Australia. Sex Transm Infect 2016; 92:286–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chow EPF, Bradshaw CS, Williamson DA, et al. Changing from clinician-collected to self-collected throat swabs for oropharyngeal gonorrhea and chlamydia screening among men who have sex with men. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58:e01215-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chow EP, Fehler G, Chen MY, et al. Testing commercial sex workers for sexually transmitted infections in Victoria, Australia: an evaluation of the impact of reducing the frequency of testing. PLoS One 2014; 9:e103081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buckingham-Jeffery E, Morbey R, House T, et al. Correcting for day of the week and public holiday effects: improving a national daily syndromic surveillance service for detecting public health threats. BMC Public Health 2017; 17:477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Australian Government Cancer Australia. Cancer won’t wait during the COVID-19 pandemic Sydney, Australia: Cancer Australia 2020. Available at: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/about-us/news/cancer-wont-wait-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 25 August 2020.

- 15. Terrence Higgins Trust. New advice on sex while managing COVID-19 risk released London, United Kingdom: Terrence Higgins Trust 2020. Available at: https://www.tht.org.uk/news/new-advice-sex-while-managing-covid-19-risk-released. Accessed 23 August 2020.

- 16. Callander D, Meunier E, DeVeau R, et al. Investigating the effects of COVID-19 on global male sex work populations: a longitudinal study of digital data [published online ahead of print June 26, 2020]. Sex Transm Infect 2020. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chow EP, Williamson DA, Fortune R, et al. Prevalence of genital and oropharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhoea among female sex workers in Melbourne, Australia, 2015–2017: need for oropharyngeal testing. Sex Transm Infect 2019; 95:398–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Turek EM, Fairley CK, Bradshaw CS, et al. Are genital examinations necessary for STI screening for female sex workers? An audit of decriminalized and regulated sex workers in Melbourne, Australia. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0231547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tang H, Hocking JS, Fehler G, et al. The prevalence of sexually transmissible infections among female sex workers from countries with low and high prevalences in Melbourne. Sex Health 2013; 10:142–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Latini A, Magri F, Dona MG, et al. Is COVID-19 affecting the epidemiology of STIs? The experience of syphilis in Rome [published online ahead of print July 27, 2020]. Sex Transm Infect 2020. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cusini M, Benardon S, Vidoni G, et al. Trend of main STIs during COVID-19 pandemic in Milan, Italy [published online ahead of print August 12, 2020]. Sex Transm Infect 2020. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blakely T, Thompson J, Carvalho N, et al. The probability of the 6‐week lockdown in Victoria (commencing 9 July 2020) achieving elimination of community transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2. Med J Aust 2020; 213:349–351.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vicotira State Government. Coronavirus update for Victoria - 5 August 2020 Melbourne, Australia: Department of Health and Human Services, State Government of Victoria, Australia 2020. Available at: https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/coronavirus-update-victoria-5-august-2020. Accessed 23 August 2020.

- 24. Australian Government Department of Health. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Health 2020. Available at: http://www9.health.gov.au/cda/source/cda-index.cfm. Accessed 23 August 2020.