Abstract

Acquired resistance to aromatase inhibitors (AIs) is a significant clinical issue in endocrine therapy for estrogen receptor (ER) positive breast cancer which accounts for the majority of breast cancer. Despite estrogen production being suppressed, ERα signaling remains active and plays a key role in most AI-resistant breast tumors. Here, we found that amphiregulin (AREG), an ERα transcriptional target and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligand, is crucial for maintaining ERα expression and signaling in acquired AI-resistant breast cancer cells. AREG was deregulated and critical for cell viability in ER+ AI-resistant breast cancer cells, and ectopic expression of AREG in hormone responsive breast cancer cells promoted endocrine resistance. RNA-sequencing and reverse phase protein array analyses revealed that AREG maintains ERα expression and signaling by activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling and upregulation of Forkhead Box M1 (FoxM1) and Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 3 (SGK3) expression. Our study uncovers a previously unappreciated role of AREG in maintaining ERα expression and signaling, and establishes the AREG-ERα crosstalk as a driver of acquired AI resistance in breast cancer.

Keywords: endocrine resistance, estrogen receptor, mTOR, FoxM1, SGK3

Introduction

Approximately 70% breast cancers are estrogen receptor positive (ER+), and endocrine therapy is the main treatment for ER+ breast cancer patients. Selective ER modulators (e.g. tamoxifen) and aromatase inhibitors (AIs) constitute the two most common endocrine treatments of ER+ breast cancer. Tamoxifen antagonizes the binding of estrogen to ERα, while AIs block estrogen biosynthesis by inhibition of aromatase, the key enzyme that converts androgens into estrogens. Clinical studies have showed that the third-generation AIs [exemestane (EXE), anastrozole (ANA) and letrozole (LET)] are superior to tamoxifen in treatment of postmenopausal women’s breast cancer (Lin and Winer 2008; Paridaens, et al. 2008). However, a proportion of patients develop resistance to AIs after prolonged AI treatment. Although various AI resistance mechanisms have been proposed, including loss of ERα expression, ERα mutation, and increased oncogenic kinase signaling or altered expression of ERα coregulators (Ma, et al. 2015), it is widely accepted that ERα signaling still plays a major role in most AI-resistant breast tumors.

Amphiregulin (AREG) is the primary epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligand in mammary tissue, and is transcriptionally up-regulated by estrogen (Ciarloni, et al. 2007). It is synthesized as a 252-amino acid transmembrane glycoprotein consisting of a signal peptide, a pro-region, a heparin-binding domain, an EGF-like domain, a transmembrane region and a carboxy-terminal cytosolic tail (Berasain and Avila 2014). Due to differential processing and glycosylation, many different sizes of AREG (9–60 kDa) are formed (Shoyab, et al. 1988; Vecchi, et al. 1998; Willmarth and Ethier 2006). AREG is a critical paracrine or autocrine regulator of estrogen action in mammary gland development required for ductal morphogenesis (Ciarloni, et al. 2007). Recent studies have reported that AREG is enriched in ER+ breast tumor cells and required for estrogen-dependent tumor growth (Meier, et al. 2020; Peterson, et al. 2015). Emerging evidence suggests that deregulation of AREG is also associated with drug resistance and metastasis in many cancers (Xu, et al. 2016).

Some breast tumors lose ERα expression thus becoming resistant to AIs, while most AI-resistant breast tumors still express ERα and rely on ERα signaling for growth despite estrogen production being suppressed during AI treatment (Aggelis and Johnston 2019; Ma, et al. 2015). Therefore, maintenance of ERα expression and signaling is important for most AI-resistant tumors. Here, we found that the ERα target AREG is deregulated and crucial for maintenance of ERα expression and signaling in acquired AI-resistant breast cancer cells, and overexpression of AREG promotes endocrine therapy resistance. Our study reveals a previously unappreciated role of AREG in sustaining ERα signaling and establishes the AREG-ERα crosstalk as a driver of acquired AI resistance in breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

MCF7aro, EXE-R, ANA-R, LET-R, and LTEDaro cells were generated and maintained as previously described (Masri, et al. 2008). HCC1428aro, HCC1428aro/LET-R and MCF7aro/tetON/SGK3 cells were generated as previously described (Wang, et al. 2017). T47Daro/LET-R cells were generated by long-term culture of T47Daro cells in phenol red-free MEM medium with 10% charcoal:dextran-stripped (CD) FBS in the presence of 1 nmol/L testosterone plus 200 nmol/L LET. MCF7aro/pMG and MCF7aro/AREG were generated by stable transfection with empty vectors pMG-H2 and AREG expression vector, respectively, and selected at 200μg/ml hygromicin B for one to two months, and the cells were maintained in normal growth medium added with 50 μg/ml hygromicin B. MCF7aro/ERE cells were generated as previously described (Lui, et al. 2008). LET-R/tetON/SGK3 cells were generated by long-term culture of MCF7aro/tetON/SGK3 cells in phenol red-free MEM medium with 10% CD FBS in the presence of 1 nmol/L Testosterone plus 200 nmol/L LET for more than 6 months.

PDXs and organoids

COH-SC31 and COH-SC1 patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) were generated as previously described (Hsu, et al. 2018). For generation of organoids or single cells for primary 2-D culture, we followed the Basic Protocol #1 described in the paper by DeRose Y et al (DeRose, et al. 2013). For 2-D primary culture, a PDX fragment was processed into single cells and directly seeded into cell culture dishes without matrix gel; For 3-D organoid cultured, a PDX fragment was processed into organoids as described in the protocol, and the organoids were seeded on the top of matrix gel of the wells in a 12-well plate or 6-well plate, and added with modified M87 medium (1ml/well for 12-well plate or 2ml /well for 6-well plate).

Generation of AREG inducible cell lines using a retroviral expression system

AREG inducible cell line T47D/tetON/AREG was generated using the Retro-X-Tet-On Advanced inducible expression system (Clontech Laboratories, Inc) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 293T cells cultured in 10-cm dishes were transiently cotransfected with pCMV-GP (gag-pol–expressing vector), a retroviral expression vector (pRetroX-Tet-On Advanced vector for the expression of the tetracycline-controlled transactivator rtTA-Advanced or pRetroX-Tight-Pur-AREG vector for the expression of AREG under the inducible response promoter, PTight), and an envelope (env)-expressing vector (pVSV-G) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 5 hours posttransfection, the culture medium containing DNA and Lipofectamine 2000 was replaced with 8 mL of fresh complete medium, and the cells were continuously cultured for an additional 48 hours before the crude viral supernatant was collected. The virus supernatant was briefly centrifuged and aliquoted, either used immediately or stored at −70°C until use.

T47D cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density to produce about 50% confluence 12 to 18 hours after seeding. To generate T47D/TetOn cells that constitutively express the tetracycline-controlled transactivator rtTA-Advanced, the T47D cells in the 6-well plate were infected with the RetroX-Tet-On Advanced virus stock, respectively. In brief, the medium was removed, 1 mL of virus stock was added to each well, and polybrene was added to a final concentration of 4 μg/mL. Twenty-four hours after infection, cells were cultured in the fresh complete medium containing 800 μg/mL G418 for about 2 weeks. The selective medium was replaced every 2–3 days. After G418 selection for 2 weeks, the G418-resistant clones were pooled and were further infected with the RetroX-Tight-Pur-AREG virus stock. Twenty-four hours after infection, the cells were cultured in the medium containing 2 μg/mL puromycin. The stable inducible cell lines were established after puromycin selection for about 2 weeks.

siRNA transfection

siRNA transfection was performed using siPORT NeoFX transfection agent (Ambion, Austin, USA) or RNAi max (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For 2D culture, cells were trypsinized and diluted in the medium at 1×105/ml. For each 6 cm dish, 10 μl siPORT NeoFX transfection agent and 15 μl 10μM AREG siRNA or siRNA negative control were diluted in 250μl OPTI-MEM I medium, respectively. For each well of 24-well plate, 1 μl siPORT NeoFX transfection agent and 1.5 μl 10μM siRNA. After being mixed and incubated for 10 min, the mixtures of siRNA and transfection agent were dispersed into 6cm dishes or 24-well plate. Cell suspensions (1×105/ml) were overlaid onto the transfection complexes at 5 ml cells/dish or 0.5 ml cells/well. For 3D organoids, ~0.5×106/mL live cells were made from PDX as described in 3D organoids culture. 15 μl RNAi max transfection agent and 22.5 μl 10μM AREG siRNA or siRNA negative control were diluted in 250μl OPTI-MEM I medium, respectively. After being mixed and incubated for 10 min, the mixtures of siRNA and transfection agent were mixed with 2ml cell suspension, and then dispersed on the top of Matrix gel of a well in 6-well plate. At 92h posttransfection, the organoids were harvested for Western blotting. Three individual AREG siRNAs (sc-39412a, sc-39412b and sc-39412c), the pooled AREG siRNA (sc-39412), EGFR siRNA (sc-29301), ERα siRNA (sc-29305), and FoxM1 siRNA (sc-270048) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (Santa Cruz, USA).

RNA-sequencing

RNA sequencing was performed as previously described (Wang, et al. 2017). Briefly, LET-R cells were reversely transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA. At 72 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested for RNA extraction. RNA was extracted using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen), and RNA sequencing was run by City of Hope Integrative Genomic Core using Hiseq2500 SE40. The result was analyzed by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

Reverse-phase protein array (RPPA)

LET-R cells were transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA for 72 h. The cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, then lysed in 250 μl lysis buffer [1% Triton X-100, 50 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1.5 nmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 100 mmol/L NaF, 10 mmol/L Na pyrophosphate, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 10% glycerol, containing freshly added protease inhibitor cocktail] for 20 min on ice. After the lysates were centrifuged at 14,000rpm for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatants were collected and measured for protein concentration using Bradford reagent (BioRad Laboratories, Irvine, USA). Each sample was adjusted to the concentration of 1.2 mg/ml, and then mixed with 4× SDS/2-ME sample buffer (40% glycerol, 8% SDS, 0.25 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; with 10% β-mercaptoethanol added before use). The samples were boiled for 5 minutes and then centrifuged for 1 minute at 2,000 rpm. The samples were stored at −80°C and sent to RPPA Core Facility at MD Anderson Cancer Center for analysis.

RT-quantitative PCR

RT-quantitative PCR was performed as described previously (Wang, et al. 2011). The primers used in real-time PCR were the following, for AREG, 5’-AGTAGTGAACCGTCCTCG-3’ and 5’-CACTTTCCGTCTTGTTTT-3’; for ESR1, 5’-CGAGTCCTGGACAAGATCACAG-3’ and 5’-TCTCCAGCAGCAGGTCATAGAG-3’; and for β-actin, 5′-CACCAACTGGGACGACAT-3′ and 5′-GCACAGCCTGGATAGCAAC-3′.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer on ice for 10 min, and then sonicated for 30s. After centrifugation, the supernatants were collected and mixed with 2×SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Protein concentration was quantified using the BioRad Protein Assay. Western blotting was performed as previously described (Wang, et al. 2014).

Clinical data

Gene expression profiles of 75 breast tumors used for analysis of AREG expression in this study were from the breast cancer dataset (NCBI accession number: GSE59515) reported in a previous study (Turnbull, et al. 2015). There were 23 letrozole nonresponders and 52 letrozole responders.

Statistical analysis

Data from MTT and RT-quantitative PCR were from 3 independent experiments, and are expressed as means ± SD. The Student’s t-test was used to analyze the statistical significance. A P value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

AREG/EGFR signaling is deregulated and critical for cell viability in acquired AI-resistant breast cancer cells

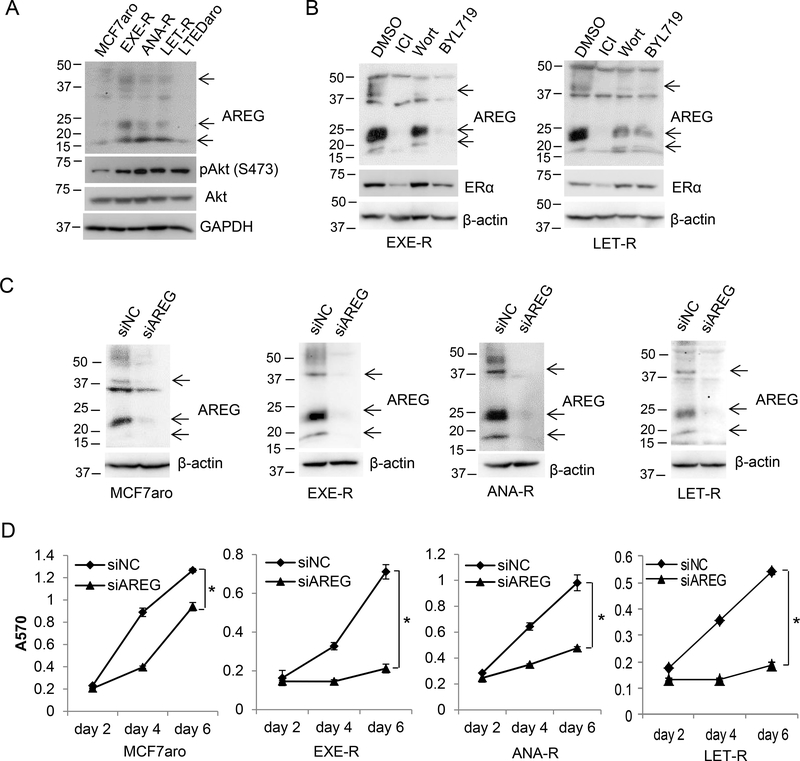

Since there is no ER+ breast cancer cell line with adequate levels of aromatase for studying acquired AI resistance, we generated three acquired AI-resistant breast cancer cell lines designated EXE-R, ANA-R and LET-R by long-term exposure of ER+ breast cancer MCF7 cells stably transfected with aromatase gene (MCF7aro) to EXE, ANA and LET, respectively (Masri, et al. 2008). These three AI-resistant cell lines retain ERα expression and rely on ERα signaling for growth. Our previous study showed that ERα target AREG is induced by steroid AI EXE but not by non-steroid AIs ANA or LET, and that AREG promotes EXE resistance (Wang, et al. 2008). Importantly, we found that AREG protein levels were also elevated in LET-R and ANA-R cells beside EXE-R cells, but not elevated in MCF7aro cells with long-term estrogen deprivation (LTEDaro) (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 1A). Moreover, either selective ER degrader ICI182,280 or phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors (wortmannin and BYL719) suppressed AREG expression in EXE-R and LET-R cells (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 1B), suggesting that both ERα and PI3K signaling are involved in AREG deregulation in all three AI-resistant cell lines.

Figure 1. AREG is deregulated and critical for cell viability in acquired AI-resistant cells.

(A) Western blotting analysis of AREG expression. All the cell lines were cultured in their normal growth media. (B) Western blotting analysis of EXE-R and LET-R cells after treatment with DMSO, 100nM ICI, 0.2μM Wortmannin, or 5μM BYL719 for 72h. (C, D) MCF7aro cells and AI-resistant cells were transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA. Cells were harvested for Western blotting analysis (C) at 72 h post-transfection or measured for cell viability by MTT assay (D) at the time indicated. *, p<0.05.

To explore the functional significance of AREG deregulation in AI-resistant cells, we first examined the effect of AREG silencing on viability of AI-resistant cells and nonresistant parental MCF7aro cells. Silencing AREG by the pooled siRNA or three individual AREG siRNAs severely impaired cell viability of all three AI-resistant cell lines, and the effect of AREG silencing on cell viability was greater in AI-resistant cells than in the parental cells (Figure 1, C and D, and Supplementary Figure 2, A–C). Similar results were obtained in HCC1428aro cells and HCC1428aro/LET-R cells (Supplementary Figure 2, D and E).

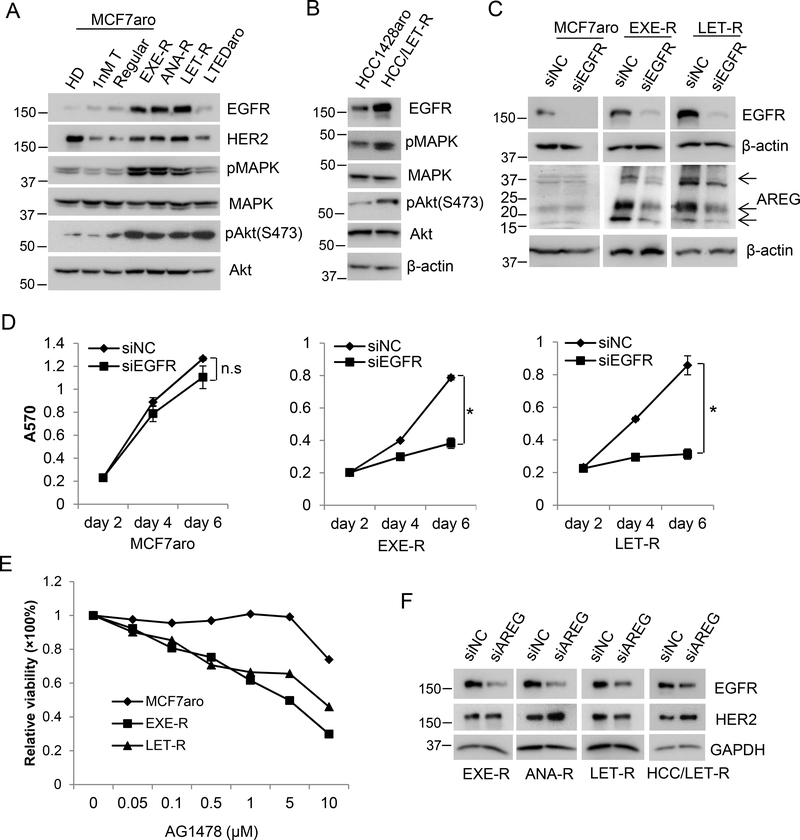

Since AREG is an EGFR ligand, we went on to examine EGFR expression and signaling in AI-resistant cells. All the AI-resistant cell lines had higher levels of EGFR expression than their parental cells (Figure 2, A and B). The levels of EGFR downstream signaling molecules phospho-MAPK, and phospho-Akt were also elevated in AI-resistant cells compared to the parental cells, confirming that EGFR signaling is activated in AI-resistant cells. EGFR silencing had a mild effect on MCF7aro cell viability, while it had a greater inhibitory effect on viability of EXE-R and LET-R cells (Figure 2, C and D), suggesting that EGFR signaling is important in AI-resistant cells. Consistent with siRNA knockdown results, both EXE-R and LET-R cells were more sensitive to EGFR inhibitors AG1478 and ZD1839 (Gefitinib) than parental MCF7aro cells (Figure 2E and Supplementary Figure 3A). Similar data was obtained when compared the effect of EGFR silencing on cell viability in HCC1428aro and HCC1428aro/LET-R cells (Supplementary Figure 3, B and C).

Figure 2. EGFR signaling is deregulated in acquired AI-resistant cells.

(A) Western blotting analysis of EGFR and the related proteins. MCF7aro cells were cultured in the normal growth medium (regular), or hormone deprived for 2 days (HD) and treated with 1nM testerosterone (T) for two days. All the other cell lines were cultured in their normal growth media. (B) Western blotting analysis of HCC1428aro cells and HCC1428aro/LET-R cells. Both cell lines were cultured in their normal growth medium. (C, D) MCF7aro, EXE-R, and LET-R cells were transfected with siRNA negative control or EGFR siRNA, respectively. Cells were harvested for Western blotting analysis (C) at 72 h post-transfection or measured for cell viability by MTT assay (D) at the time indicated. n.s: not significant; *, p<0.05. (E) The inhibition of AG1478 on MCF7aro cells and AI-resistant cells. MCF7aro, EXE-R and LET-R cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of AG1478 for 96h, and cell viability was measured by MTT. The inhibition was calculated compared to solvent treatment. (F) Western blotting analysis of four AI-resistant cell lines after transfection with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA.

A previous study has shown that AREG-stimulated EGFR has a long half-life resulting in overexpression of EGFR (Willmarth, et al. 2009). Therefore, we tested whether elevated AREG levels contribute to higher levels of EGFR expression in acquired AI-resistant cells. As shown in Figure 2F, AREG knockdown significantly reduced expression of EGFR but not HER2 in all four AI-resistant cell lines. Furthermore, silencing of EGFR significantly suppressed AREG expression in EXE-R and LET-R cells but not in MCF7aro cells (Figure 2C), suggesting that AREG and EGFR positively regulate each other and may form a self-sustaining loop in AI-resistant breast cancer cells.

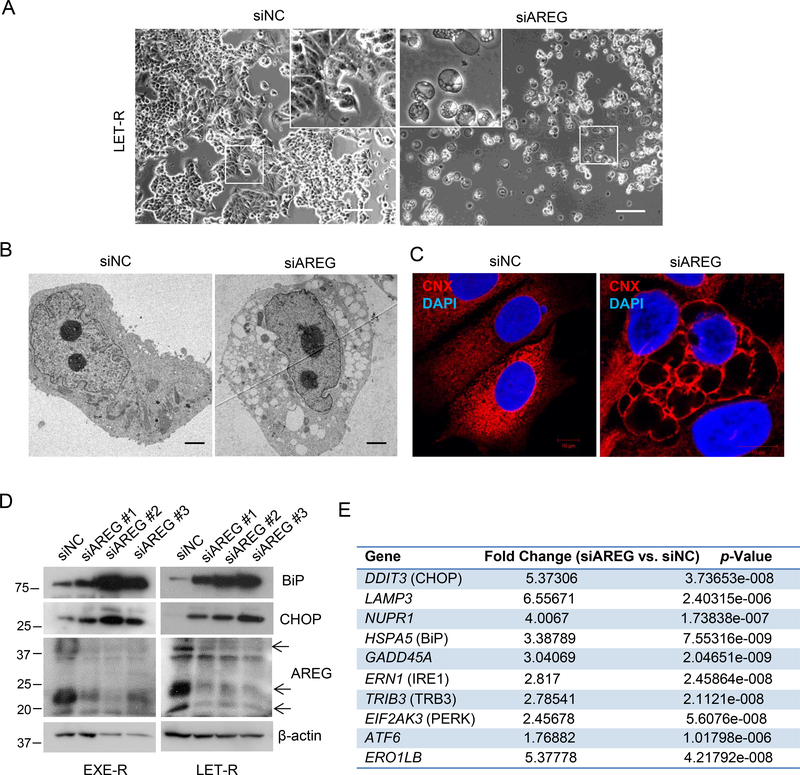

AREG is required for EnR homeostasis of AI-resistant breast cancer cells

Massive cytoplasmic vacuoles were found in AREG knockdown AI-resistant cells (Figure 3A). Transmission electron microscopy showed that the vacuoles in AREG knockdown LET-R cells lacked any visible cytoplasmic materials thus ruling them out as autophagosomes (Figure 3B). Immunofluorescence microscopy by immunostaining for endoplasmic reticulum (EnR) membrane protein Calnexin indicated that the vacuoles were derived from EnR resulting from EnR dilation (Figure 3C), implying that the resistant cells underwent extensive EnR stress upon AREG silencing. Figure 3D showed that silencing AREG by three individual siRNAs in EXE-R and LET-R cells all dramatically induced the expression of Binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) and the transcription factor C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), the markers of EnR stress. In contrast, silencing AREG in parental MCF7aro cells moderately increased the expression of BiP and CHOP (Supplementary Figure 4A), indicating that AI-resistant cells increase dependency on AREG for EnR homeostasis. RNA-sequencing analysis of LET-R cells transfected with AREG siRNA or siRNA negative control also showed that the levels of EnR stress markers including HSPA5 (BiP), DDIT3 (CHOP), ERN1 (IRE1α), EIF2AK3 (PERK) and GADD45A were significant induced in LET-R cells after AREG silencing (Figure 3E). Induction of EnR stress by AREG silencing was also observed in HCC1428aro/LET-R cells (Supplementary Figure 4B).

Figure 3. AREG is required for EnR homoestasis of acquired AI-resistant cells.

(A) Phase contrast microscopy of LET-R cells transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA for 72h. Scale bar: 50μm. (B) Electron microscopy of LET-R cells transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA for 72h. Scale bar: 2μm. (C) Immunofluorescence microscopy of LET-R cells transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA. After transfection for 72 h, cells were fixed and immunostained with anti-calnexin (CNX). After immunostaining, the cells were mounted in DAPI solution and imaged under a confocal microscope. DAPI stained nuclei blue. CNX was shown in red. Scale bar: 10μm. (D) Western blotting analysis of EXE-R and LET-R cells after transfection with siRNA negative control or three individual AREG siRNAs, respectively. (E) The list of EnR stress-related genes upregulated in AREG knockdown LET-R cells in RNA-Sequencing analysis.

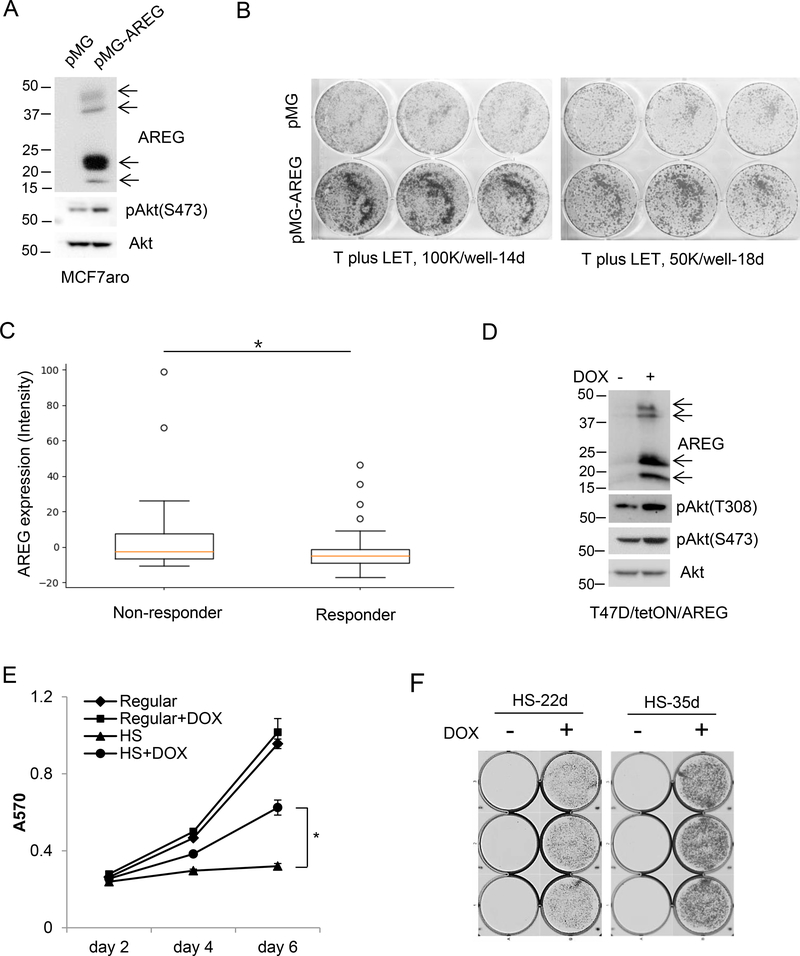

Overexpression of AREG promotes endocrine therapy resistance

Giving that AREG plays a critical role in cell viability of AI-resistant cells, we tested whether overexpression of AREG in hormone-responsive breast cancer cells promotes resistance to AI, we generated MCF7aro cells stably transfected with AREG expression vector (MCF7aro/AREG) or empty vector (MCF7aro/pMG) (Figure 4A). Under normal growth medium, MCF7aro/AREG cells proliferated slightly faster than MCF7aro/pMG control cells (Supplementary Figure 5A). When cultured in hormone-depleted medium in the presence of testosterone plus LET, MCF7aro/AREG cells were less suppressed by LET than MCF7aro/pMG control cells (Figure 4B), indicating that overexpression of AREG promotes relative resistance to LET. Gene profiles of 75 biopsy breast tumors (NCBI accession number: GSE59515) (http://ctgs.biohackers.net/GSE59515/plot-quantities/) showed that AREG expression levels were significantly higher in LET nonresponders than in LET responders (Figure 4C), supporting that high AREG levels could be associated with non-responsiveness of breast tumors to LET treatment.

Figure 4. Overexpression of AREG promotes endocrine therapy resistance.

(A) Western blotting analysis of MCF7aro cells stably transfected with empty vector pMG or AREG expressing vector. (B) MCF7aro/pMG and MCF7aro/pMG-AREG cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 100,000 cells/well or 50,000 cells/well, and cultured in hormone-stripped medium and treated with 1nM testosterone plus 200nM LET for 14 days and 18 days, respectively. Cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. Images were taken using a scanner. (C) Plot of AREG expression vs. clinical response to LET in 75 breast tumors (23 nonresponders and 52 responders) from breast cancer dataset (GSE59515). The mean of AREG expression intensity was 7.413 in nonresponderand and −2.816 in responders. *, p=0.0222 by Student’s t test. (D) Western blotting analysis of T47D/tetON/AREG cells cultured in regular medium in the presence or absence of 100ng/ml DOX for 48h. (E) T47D/tetON/AREG cells were cultured in normal growth medium (regular) or hormone-stripped medium (HS) in the presence or absence of 100ng/ml DOX. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. *, p<0.05. (F) T47D/tetON/AREG cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 50,000 cells/well, and cultured in hormone-stripped medium in the presence or absence of 100ng/ml DOX. After 22 days and 35 days, cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. Image was captured by Cell3 iMager duos system.

To further examine whether AREG promotes other endocrine therapy resistance, we used retroviral inducible expression system to generate the AREG-inducible cell lines designated T47D/TetON/AREG, in which AREG expression is inducible by doxycycline (DOX) (Figure 4D). DOX induction of AREG expression in T47D/TetON/AREG cells had no effect on cell proliferation under normal growth medium, but it largely overcame hormone deprivation-induced suppression of cell proliferation (Figure 4, E and F). Induction of AREG expression also rendered T47D/TetON/AREG cells fully resistant to antiestrogen 4-hydroxytamoxifen and partially resistant to ICI182,780 (Supplementary Figure 5, B–D). Together, these data suggest that overexpression of AREG could promote resistance to endocrine therapy agents AI, tamoxifen and fulvestrant (ICI182,780).

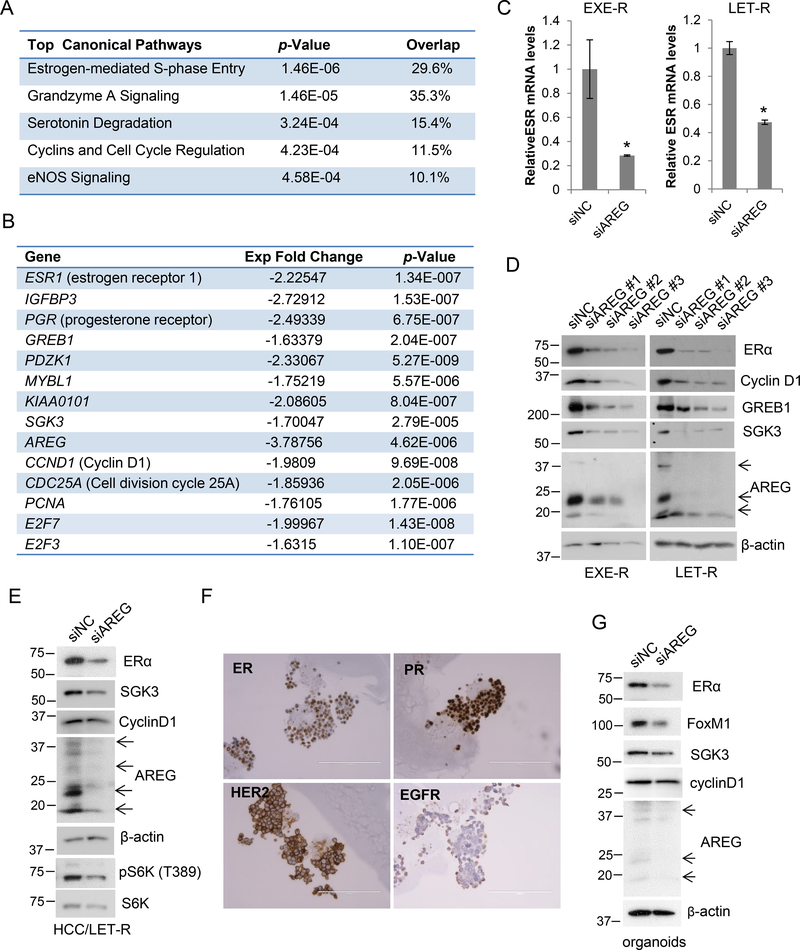

AREG is crucial for ERα expression and signaling

To gain an insight into the molecular basis for the role of AREG in AI-resistant cells, we performed an RNA-sequencing analysis on LET-R cells transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA. Unexpectedly, Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) of RNA-sequencing data revealed that the top pathway suppressed by AREG silencing was estrogen-mediated S-phase entry (Figure 5A). The expressions of ESR1 (the gene coding ERα), CCND1 (the gene coding cyclin D1) and many other well-known ERα target genes such as PGR (the gene coding progesterone receptor), GREB1, IGFBP3, PDZK1, MYBL1 and SGK3 were significantly decreased (Figure 5B). The proliferation-associated genes (e.g., E2F3, E2F7, CCND1, CDC25A and PCNA) were also significantly downregulated. In contrast, ESR2 (the gene coding ERβ) mRNA levels were not significantly changed. Reduction in ESR1 mRNA levels by AREG knockdown was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Figure 5C). Western blotting analysis showed that silencing AREG by three individual AREG siRNAs all dramatically reduced protein levels of ERα and its targets such as GREB1 and SGK3 in EXE-R and LET-R cells (Figure 5D). Downregulation of ERα and SGK3 expression by AREG silencing was also confirmed in HCC1428aro/LET-R cells (Figure 5E).

Figure 5. AREG maintains ERα expression and signaling.

(A, B) RNA-Sequencing analysis of LET-R cells transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA. The top canonical pathways affected by knockdown of AREG analyzed by Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) were shown in (A). The expression changes of ESR1 (the gene coding ERα) and ERα-target genes as well as genes involving cell proliferation were shown in (B). (C) RT-qPCR analysis of ESR1 mRNA levels after transfection with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA in EXE-R and LET-R cells. (D) Western blotting analysis of EXE-R and LET-R cells after transfected with siRNA negative control or three individual AREG siRNAs, respectively. (E) Western blotting analysis of HCC1428aro/LET-R cells transfected with siRNA negative control or the pooled AREG siRNA. (F) Immunohistochemistry staining of COH-SC31 organoids for detection of ERα, PR, HER2 and EGFR. Organoids were similar to the original tumor in expression of ERα, PR, HER2. (G) Western blotting analysis of COH-SC31 organoids transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA for 90h.

To test whether regulation of ERα by AREG is specific to AI-resistant cell lines, we also examined the effect of AREG silencing on ERα expression in non-resistant cell lines. Silencing AREG suppressed ERα expression in MCF7aro and HCC1428aro cells, but the suppression effect was less in the parental cells compared to that in their counterpart AI-resistant cells (Supplementary Figure 6, A and B). To extend this finding to other models outside the established cell lines, we utilized PDXs and organoids, which better recapitulate human cancer histology in vivo (Yang, et al. 2019). Using COH-SC31 and COH-SC1 PDXs which were generated from two different ER+ advanced breast tumors, respectively (Hsu, et al. 2018), we showed that AREG silencing dramatically reduced ERα expression in both 2-D primary culture (Supplementary Figure 6, C and D) and 3-D organoid culture that maintained the feature of the major molecular markers (ER, PR, HER2 and EGFR) of its original PDX (Figure 5, F and G).

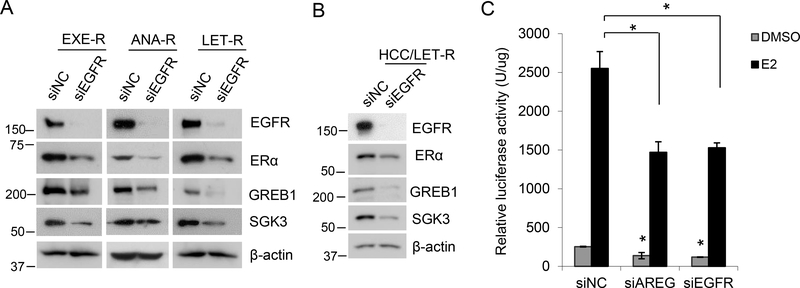

Given AREG is an EGFR ligand, we further investigated whether EGFR regulates ERα expression and signaling. Silencing EGFR reduced expression of ERα and its targets GREB1 and SGK3 in all the AI-resistant cell lines (Figure 6, A and B). Using an estrogen-responsive element luciferase reporter assay, we showed that silencing EGFR or AREG significantly suppressed both estrogen-dependent and -independent ERα activities in MCF7aro cells stably transfected with a promoter reporter plasmid, pGL3-Luc, containing three repeats of estrogen responsive element (ERE) (Figure 6C), further supporting that AREG and EGFR are important for ERα signaling.

Figure 6. EGFR regulates ERα expression and signaling.

(A) Western blotting analysis of AI-resistant cells transfected with siRNA negative control or EGFR siRNA for 72h. (B) Western blotting analysis of HCC1428aro/LET-R cells transfected with siRNA negative control or EGFR siRNA for 72h. (C) Luciferase reporter assay for ERα transactivity. MCF7aro/ERE cells were cultured in hormone-deprived medium and transfected with siRNA negative control, AREG siRNA or EGFR siRNA. Meanwhile, cells were treated with or without 10nM E2. At 48h posttreatment, cells were harvested for luciferase activity assay. Luciferase activity was normalized to protein concentration. *, p<0.05 vs. siRNA NC, n=3.

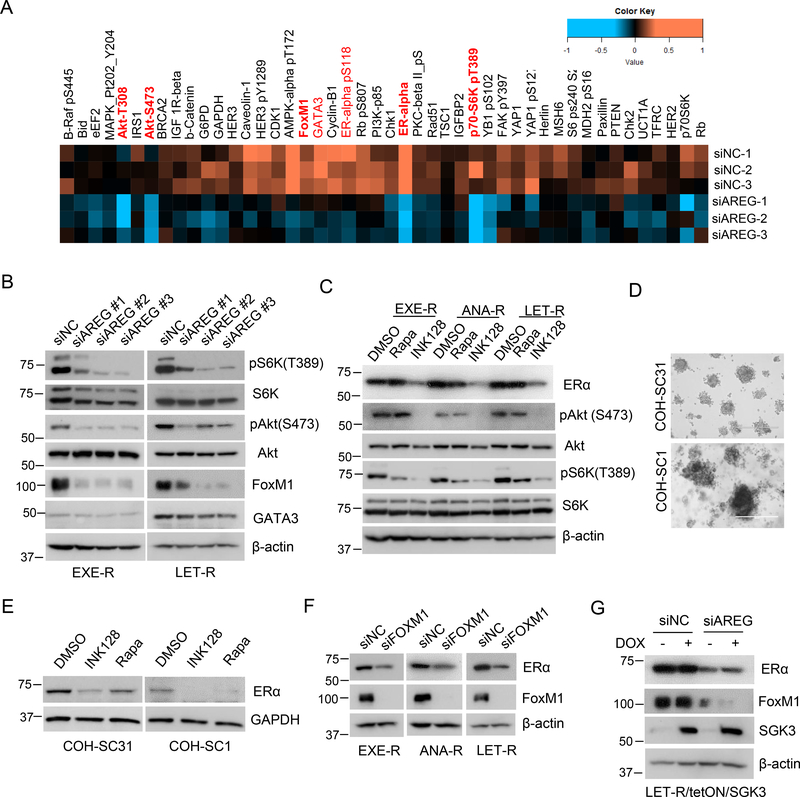

AREG sustains ERα signaling by activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling and upregulation of FoxM1 and SGK3 expression

To investigate the mechanism for maintenance of ERα expression and signaling by AREG in AI-resistant cells, we performed an RPPA analysis with LET-R cells transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA (Supplementary Figure 7A). Consistent with RNA-sequencing data, RPPA data showed that ERα protein levels were significantly decreased in AREG knockdown cells. The levels of phospho-Akt at both Ser473 and Thr308 sites were also decreased (Figure 7A). Akt is a critical PI3K downstream kinase, and its phosphorylations at Thr308 site and Ser486 sites are mediated by PDK1 and mTORC2 (mTOR Complex 2), respectively (Manning and Toker 2017). Akt activates mTORC1 (mTOR Complex 1) which phosphorylates p70S6K at Thr308. The levels of phospho-p70S6K (T389) were also decreased in AREG knockdown cells in our RPPA data (Figure 7A). These findings, together with our results that ectopic expression of AREG resulted in elevated phospho-Akt levels in MCF7aro and T47D cell lines (Figure 4, A and D), strongly suggest that AREG sustains PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling. We confirmed those RPPA data with individual Western blots (Figure 7B). Our data indicate that both mTORC2 and mTORC1 signaling are inhibited in AREG knockdown AI-resistant cells, since silencing AREG decreased both pAkt (S473) and pS6K(T308) levels (Figure 7B). Previously, we observed that mTOR dual inhibitor MLN (INK128) decreases ERα expression in two PDXs COH-SC31 and COH-SC1 (Hsu, et al. 2018), implying that mTOR signaling regulates ERα expressions in vivo. Downregulation of expression ERα by INK128 was confirmed with all four AI-resistant cell lines and the organoids from COH-SC31 and COH-SC1 PDXs (Figure 7, C–E, and Supplementary Figure 7B), implying that activation of mTOR signaling by AREG might be one of the mechanisms for AREG sustaining ERα expression and signaling.

Figure 7. AREG sustains ERα signaling by activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling and upregulation of FoxM1 and SGK3 expression.

(A) The partial heatmap of RPPA of LET-R cells transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA, which highlights most of downregulated proteins in AREG knockdown cells. The full heatmap was shown in supplementary Fig.7A. (B) Western blotting analysis of AI-resistant cells transfected with siRNA negative control or 3 individual AREG siRNAs, respectively. (C) Western blotting analysis of AI-resistant cells treated with 0.5μM rapamycin or 0.5μM INK128. (D) Light microscopy of the organoids generated from COH-SC31 and COH-SC1 PDXs. (E) Western blotting analysis of COH-SC31 and COH-SC1 organoids treated with 0.5μM rapamycin or 0.5μM INK128. (F) Western blotting analysis of AI-resistant cells transfected with siRNA negative control or FoxM1 siRNA. (G) Western blotting analysis of LET-R/TetON/SGK3 cells transfected with siRNA negative control or AREG siRNA in the presence or absence of doxycycline.

In our RPPA data, the levels of ERα pioneer factors GATA Binding Protein 3 (GATA3) and Forkhead Box M1 (FoxM1) were also decreased in AREG knockdown cells ( Figure 7A). Both GATA3 and FoxM1 are ERα targets and also regulate ERα expression and transcriptional activity (Eeckhoute, et al. 2007; Madureira, et al. 2006; Sanders, et al. 2013). We confirmed that FoxM1 levels were dramatically decreased after AREG silencing in all the AI-resistant cell lines (Figure 7B and Supplementary Figure 7C), COH-SC31 organoids (Figure 5G) and the 2D primary cultures of COH-SC31 and COH-SC1 PDXs (Supplementary Figure 6, C and D). Moreover, ectopic expression of AREG could block ICI182,780-induced FoxM1 depletion (Supplementary Figure 7D), suggesting that FoxM1 is a real AREG target. In contrast, GATA3 levels were decreased, not altered or increased after AREG silencing depending on cell contend (Figure 7B, and Supplementary Figure 6C and Figure 7C). Consistent with the previous report showing FoxM1 is a physiological regulator of ERα expression in breast cancer cells (Madureira, et al. 2006), silencing FoxM1 caused a significant reduction in ERα expression in AI-resistant cells (Figure 7F). The data suggest that FoxM1 is also an important AREG target mediating maintenance of ERα expression and signaling in AI-resistant breast cancer cells.

Recently, we have reported that SGK3, a PI3K downstream kinase, sustains ERα signaling in acquired AI-resistant cells (Wang, et al. 2017). Given silencing AREG reduced SGK3 levels in all the tested cell lines and organoids, we tested whether SGK3 is involved in AREG maintenance of ERα signaling. Using SGK3-inducible LET-R cells, we showed that DOX induction of SGK3 expression moderately attenuated AREG silencing-induced ERα downregulation (Figure 7G), indicating that SGK3 might also be partially involved in AREG sustaining ERα expression and signaling in acquired AI-resistant cells.

Discussion

Although a number of mechanisms have been suggested for AI resistance, in most situations, ERα is still the key player in AI resistance (Ma, et al. 2015). It is known that ERα signaling remains active through mutations or cross-talk with growth factor signaling pathways in AI-resistant breast cancer cells. Active ERα can transcriptionally upregulate AREG expression. In this study, AREG was found to maintain ERα expression and signaling via multiple mechanisms such as PI3K/Akt/mTOR, FoxM1 and SGK3. Therefore, our study suggests that AREG is a key ERα target that sustains ERα signaling to drive acquired AI resistance of ER+ breast cancer cells.

Compared to EGF, AREG has lower affinity with EGFR but stabilizes EGFR (Willmarth, et al. 2009), which might account for the functional difference between these two ligands. EGF downregulates ERα expression, and EGFR expression is usually reversely correlated with ERα expression in breast cancer (Jeong, et al. 2019). However, high expression of EGFR in ER+ breast cancer patients is associated with poor prognosis and overall survival (Jeong, et al. 2019; Quintela, et al. 2005). EGFR signaling activates PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MAPK pathways, and activation of either pathway could result in ligand-independent activation of ERα via phosphorylation of ERα and/or the ERα coregulators, and thus confer endocrine therapy resistance (Campbell, et al. 2001; Miller, et al. 2011; Osborne, et al. 2005). We found that all the AI-resistant cell lines have elevated levels of EGFR and its downstream signaling molecules pMAPK and pAkt, and silencing of AREG or EGFR significantly inhibits AI-resistant cell proliferation and suppresses ERα expression and signaling, suggesting that AREG/EGFR signaling is important for maintaining ERα signaling. Because AREG and EGFR can form a positive self-sustaining autocrine loop in AI-resistant cells, and both are deregulated in acquired AI-resistant cells, AREG/EGFR signaling becomes very important to AI-resistant cells. In contrast, in nonresistant ER+ breast cancer cells or tumors, EGFR levels are usually low thus limiting AREG function in these cells.

Deregulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling is a characteristic of endocrine resistant breast cancer (Araki and Miyoshi 2018; Miller, et al. 2011). Significantly, we found that PI3K signaling positively regulates AREG expression while AREG activates PI3K signaling. There are intensive cross-talks between ERα and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling. Akt, mTOR and its direct target S6K can directly phosphorylate and activate ERα (Alayev, et al. 2016; Campbell, et al. 2001; Yamnik, et al. 2009). Clinically, combination of endocrine therapy inhibitors (e.g. AI or fulvestrant) with mTORC1 inhibitor (e.g. everolimus) has resulted in significant improvement in relapse free survival of advanced breast cancer patients (Baselga, et al. 2012; Kornblum, et al. 2018), confirming the critical role of both ERα and mTOR signaling in breast cancer. Our study showed that AREG activates mTOR signaling, and the latter sustains ERα expression and signaling in AI-resistant cells, although the detailed mechanism by which mTOR regulates ERα expression remains to be determined. Therefore, AREG is an important molecule connecting ERα and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathways in AI-resistant breast cancer cells.

Estrogen/ERα signaling is a major driver for ER+ breast cancer. Both FoxM1 and SGK3 are transcriptionally upregulated by ERα and also regulate ERα expression and transcriptional activity in breast cancer cells (Madureira, et al. 2006; Millour, et al. 2010; Sanders, et al. 2013; Wang, et al. 2011; Xu, et al. 2009; Xu, et al. 2012). Here, we found that AREG is important for FoxM1 and SGK3 expression, and silencing AREG could disrupt the loops between them and ERα. FoxM1 is a key regulator of cell cycle and plays an important role in ERα signaling (Madureira, et al. 2006; Sanders, et al. 2013), and it has also been reported to mediate tamoxifen resistance (Bergamaschi, et al. 2014; Millour, et al. 2010). A recent study has reported that FoxM1 is an AREG target (Stoll, et al. 2016). We found that silencing AREG depletes FoxM1 expression in all the tested cell lines and organoids, and ectopic expression of AREG blocks ICI182,780-induced FoxM1 depletion. Our study confirms that FoxM1 is a bona fide AREG target and may mediate AREG maintenance of ERα expression and signaling. SGK3 is a PI3K downstream kinase and has been found to play a critical role in Akt-independent signaling downstream of oncogenic PIK3CA mutation in cancers including breast cancer (Vasudevan, et al. 2009). Same as AREG, SGK3 is also well positively correlated with ERα expression in breast tumors, and is overexpressed in AI-resistant breast cancer cells (Wang, et al. 2011; Wang, et al. 2017; Xu, et al. 2012). AREG regulates SGK3 expression, and overexpression of SGK3 can partially attenuate AREG silencing-induced ERα depletion, suggesting that SGK3 partially mediates AREG sustaining ERα signaling in AI-resistant cells.

In summary, our current study reveals that AREG is a key ERα target that sustains ERα signaling when estrogen production is suppressed by AI, and the AREG-ERα positive feedback loop is a driver of acquired AI resistance in breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jinhui Wang and Charles Warden for assistance with RNA-Seq, Dr. Xiwei Wu for microarray analysis, and Dr. Aimin Li for assistance with immunohistochemistry staining. We also thank the RPPA core at the MD Anderson Cancer Center for RPPA analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by Carr Baird grant (to YW) and Hope Idol 2012 (to SC), the ThinkCure grant (to SC) and the NIH grant CA44735 (to SC). The Analytical Cytometry Core, Bioinformatics core, Electron Microscope Core, Light Microscope Core, and Integrative Genomics core were supported by the National Cancer Institute of the NIH under award P30CA33572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Data availability: RNA-seq data are deposited in GEO (NCBI accession number: GSE148800). All the remaining data are contained in this article.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

References

- Aggelis V & Johnston SRD 2019. Advances in Endocrine-Based Therapies for Estrogen Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. Drugs 79 1849–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alayev A, Salamon RS, Berger SM, Schwartz NS, Cuesta R, Snyder RB & Holz MK 2016. mTORC1 directly phosphorylates and activates ERalpha upon estrogen stimulation. Oncogene 35 3535–3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki K & Miyoshi Y 2018. Mechanism of resistance to endocrine therapy in breast cancer: the important role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR in estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer 25 392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, Burris HA 3rd, Rugo HS, Sahmoud T, Noguchi S, Gnant M, Pritchard KI, Lebrun F, et al. 2012. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 366 520–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berasain C & Avila MA 2014. Amphiregulin. Semin Cell Dev Biol 28 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschi A, Madak-Erdogan Z, Kim YJ, Choi YL, Lu H & Katzenellenbogen BS 2014. The forkhead transcription factor FOXM1 promotes endocrine resistance and invasiveness in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer by expansion of stem-like cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res 16 436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RA, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Patel NM, Constantinidou D, Ali S & Nakshatri H 2001. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT-mediated activation of estrogen receptor alpha: a new model for anti-estrogen resistance. J Biol Chem 276 9817–9824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarloni L, Mallepell S & Brisken C 2007. Amphiregulin is an essential mediator of estrogen receptor alpha function in mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 5455–5460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRose YS, Gligorich KM, Wang G, Georgelas A, Bowman P, Courdy SJ, Welm AL & Welm BE 2013. Patient-derived models of human breast cancer: protocols for in vitro and in vivo applications in tumor biology and translational medicine. Curr Protoc Pharmacol Chapter 14 Unit14 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhoute J, Keeton EK, Lupien M, Krum SA, Carroll JS & Brown M 2007. Positive cross-regulatory loop ties GATA-3 to estrogen receptor alpha expression in breast cancer. Cancer Res 67 6477–6483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PY, Wu VS, Kanaya N, Petrossian K, Hsu HK, Nguyen D, Schmolze D, Kai M, Liu CY, Lu H, et al. 2018. Dual mTOR Kinase Inhibitor MLN0128 Sensitizes HR(+)/HER2(+) Breast Cancer Patient-Derived Xenografts to Trastuzumab or Fulvestrant. Clin Cancer Res 24 395–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Y, Bae SY, You D, Jung SP, Choi HJ, Kim I, Lee SK, Yu J, Kim SW, Lee JE, et al. 2019. EGFR is a Therapeutic Target in Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem 53 805–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblum N, Zhao F, Manola J, Klein P, Ramaswamy B, Brufsky A, Stella PJ, Burnette B, Telli M, Makower DF, et al. 2018. Randomized Phase II Trial of Fulvestrant Plus Everolimus or Placebo in Postmenopausal Women With Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer Resistant to Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy: Results of PrE0102. J Clin Oncol 36 1556–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin NU & Winer EP 2008. Advances in adjuvant endocrine therapy for postmenopausal women. J Clin Oncol 26 798–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui K, Tamura T, Mori T, Zhou D & Chen S 2008. MCF-7aro/ERE, a novel cell line for rapid screening of aromatase inhibitors, ERalpha ligands and ERRalpha ligands. Biochem Pharmacol 76 208–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma CX, Reinert T, Chmielewska I & Ellis MJ 2015. Mechanisms of aromatase inhibitor resistance. Nat Rev Cancer 15 261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madureira PA, Varshochi R, Constantinidou D, Francis RE, Coombes RC, Yao KM & Lam EW 2006. The Forkhead box M1 protein regulates the transcription of the estrogen receptor alpha in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 281 25167–25176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BD & Toker A 2017. AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating the Network. Cell 169 381–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masri S, Phung S, Wang X, Wu X, Yuan YC, Wagman L & Chen S 2008. Genome-wide analysis of aromatase inhibitor-resistant, tamoxifen-resistant, and long-term estrogen-deprived cells reveals a role for estrogen receptor. Cancer Res 68 4910–4918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier DR, Girtman MA, Lofgren KA & Kenny PA 2020. Amphiregulin deletion strongly attenuates the development of estrogen receptor-positive tumors in p53 mutant mice. Breast Cancer Res Treat 179 653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TW, Balko JM & Arteaga CL 2011. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29 4452–4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millour J, Constantinidou D, Stavropoulou AV, Wilson MS, Myatt SS, Kwok JM, Sivanandan K, Coombes RC, Medema RH, Hartman J, et al. 2010. FOXM1 is a transcriptional target of ERalpha and has a critical role in breast cancer endocrine sensitivity and resistance. Oncogene 29 2983–2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne CK, Shou J, Massarweh S & Schiff R 2005. Crosstalk between estrogen receptor and growth factor receptor pathways as a cause for endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11 865s–870s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paridaens RJ, Dirix LY, Beex LV, Nooij M, Cameron DA, Cufer T, Piccart MJ, Bogaerts J & Therasse P 2008. Phase III study comparing exemestane with tamoxifen as first-line hormonal treatment of metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women: the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol 26 4883–4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson EA, Jenkins EC, Lofgren KA, Chandiramani N, Liu H, Aranda E, Barnett M & Kenny PA 2015. Amphiregulin Is a Critical Downstream Effector of Estrogen Signaling in ERalpha-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancer Res 75 4830–4838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintela I, Corte MD, Allende MT, Vazquez J, Rodriguez JC, Bongera M, Lamelas M, Gonzalez LO, Vega A, Garcia-Muniz JL, et al. 2005. Expression and prognostic value of EGFR in invasive breast cancer. Oncol Rep 14 1655–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders DA, Ross-Innes CS, Beraldi D, Carroll JS & Balasubramanian S 2013. Genome-wide mapping of FOXM1 binding reveals co-binding with estrogen receptor alpha in breast cancer cells. Genome Biol 14 R6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoyab M, McDonald VL, Bradley JG & Todaro GJ 1988. Amphiregulin: a bifunctional growth-modulating glycoprotein produced by the phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-treated human breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85 6528–6532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll SW, Stuart PE, Swindell WR, Tsoi LC, Li B, Gandarillas A, Lambert S, Johnston A, Nair RP & Elder JT 2016. The EGF receptor ligand amphiregulin controls cell division via FoxM1. Oncogene 35 2075–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull AK, Arthur LM, Renshaw L, Larionov AA, Kay C, Dunbier AK, Thomas JS, Dowsett M, Sims AH & Dixon JM 2015. Accurate Prediction and Validation of Response to Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 33 2270–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan KM, Barbie DA, Davies MA, Rabinovsky R, McNear CJ, Kim JJ, Hennessy BT, Tseng H, Pochanard P, Kim SY, et al. 2009. AKT-independent signaling downstream of oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in human cancer. Cancer Cell 16 21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchi M, Rudolph-Owen LA, Brown CL, Dempsey PJ & Carpenter G 1998. Tyrosine phosphorylation and proteolysis. Pervanadate-induced, metalloprotease-dependent cleavage of the ErbB-4 receptor and amphiregulin. J Biol Chem 273 20589–20595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Masri S, Phung S & Chen S 2008. The role of amphiregulin in exemestane-resistant breast cancer cells: evidence of an autocrine loop. Cancer Res 68 2259–2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xu W, Zhou D, Neckers L & Chen S 2014. Coordinated regulation of serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 3 by a C-terminal hydrophobic motif and Hsp90-Cdc37 chaperone complex. J Biol Chem 289 4815–4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhou D, Phung S, Masri S, Smith D & Chen S 2011. SGK3 is an estrogen-inducible kinase promoting estrogen-mediated survival of breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol 25 72–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhou D, Phung S, Warden C, Rashid R, Chan N & Chen S 2017. SGK3 sustains ERalpha signaling and drives acquired aromatase inhibitor resistance through maintaining endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114 E1500–E1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmarth NE & Ethier SP 2006. Autocrine and juxtacrine effects of amphiregulin on the proliferative, invasive, and migratory properties of normal and neoplastic human mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 281 37728–37737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmarth NE, Baillo A, Dziubinski ML, Wilson K, Riese DJ, 2nd, & Ethier SP 2009. Altered EGFR localization and degradation in human breast cancer cells with an amphiregulin/EGFR autocrine loop. Cell Signal 21 212–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Liao L, Qin J, Xu J, Liu D & Songyang Z 2009. Identification of Flightless-I as a substrate of the cytokine-independent survival kinase CISK. J Biol Chem 284 14377–14385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Wan M, He Q, Bassett RL Jr, Fu X, Chen AC, Shi F, Creighton CJ, Schiff R, Huo L, et al. 2012. SGK3 is associated with estrogen receptor expression in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 134 531–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Chiao P & Sun Y 2016. Amphiregulin in Cancer: New Insights for Translational Medicine. Trends Cancer 2 111–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamnik RL, Digilova A, Davis DC, Brodt ZN, Murphy CJ & Holz MK 2009. S6 kinase 1 regulates estrogen receptor alpha in control of breast cancer cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 284 6361–6369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Yang S, Li X, Li B, Li Y, Zhang X, Ma Y, Peng X, Jin H, Fan Q, et al. 2019. Tumor organoids: From inception to future in cancer research. Cancer Lett 454 120–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.