Abstract

Background:

This study examined the interactive effects of acculturation (host culture acquisition) and enculturation (heritage culture retention) on Latina/o caregivers’ beliefs about their child completing the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine series.

Methods:

Participants were 161 caregiver-child dyads from Florida. Using multiple regression, caregiver knowledge and health beliefs (perceived threat, benefits, barriers, subjective norms, and self-efficacy) about series completion were predicted from caregivers’ scores on acculturation, enculturation, and their interaction, controlling for sociodemographics.

Results:

Acculturation and enculturation interacted to predict knowledge, benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy. Caregivers with high acculturation scores generally supported series completion, regardless of their enculturation score. However, when acculturation was low, caregivers who retained more (vs. less) of their heritage culture were more knowledgeable and held more favorable beliefs about series completion.

Discussion:

Findings highlight the importance of independently assessing acculturation and enculturation in Latina/o immigrant populations. Overlooking enculturation may lead to incomplete conclusions about acculturation and health.

Keywords: acculturation, Hispanic Americans, papillomavirus vaccines, psychosocial factors

Background and Theoretical Framework

Immigrating to another country can have significant effects on people’s health and health behavior [1–4]. Acculturation, or the extent to which people adopt the beliefs, values, and practices of the country to which they immigrate (i.e., the host or receiving country), plays an important role in this process [1, 5]. Among immigrants from Mexico and other Latin American countries living in the United States, for example, acculturation is associated with a variety of health behaviors (e.g., substance abuse, dietary behavior, use of health care services) and health outcomes (e.g., obesity, low birthweight) [1, 2, 6–8].

One central pathway through which acculturation may affect immigrant health is by altering people’s beliefs about health-related behavior [1, 9]. Theories of health behavior propose that people’s decisions about whether to perform a health behavior are rooted in their underlying beliefs about the behavior [10, 11]. Because health beliefs play such an important role in health-related decision making, it is vital to understand how acculturation may shape immigrants’ health beliefs. Nevertheless, relatively little research has examined the relationship between acculturation and health beliefs.

When investigating the relationship between acculturation and health it is important to independently assess both the acquisition of the host culture (i.e., acculturation) and the retention of heritage culture (i.e., enculturation or the extent to which an individual adheres to or retains the beliefs, values, and practices of the heritage culture). Until recently the literature largely ignored the role of enculturation for health and health-related behavior [2, 5, 12]. The nearly exclusive focus on assimilation to the receiving culture may reflect early conceptualizations of acculturation as a unidimensional process in which immigrants were presumed to automatically lose aspects of their heritage culture as they adopted aspects of the host culture [13]. More recent models, however, move beyond defining acculturation as a single continuum with heritage culture retention on one end and host culture adoption on the other end. Rather, acculturation and enculturation are conceptualized as two independent dimensions [5, 14, 15]. Using a two dimensional conceptualization allows researchers to examine whether acculturation and enculturation exert additive or interactive effects on outcomes [9, 15].

Although Latina/o parents are generally quite accepting of childhood vaccination [16–22], little is known about the association between acculturation and Latina/o parents’ beliefs about childhood immunization [23]. A study of Mexican American mothers in Texas found that mothers who scored higher on acculturation reported less favorable attitudes toward immunization, less obligation for keeping their child up-to-date on vaccinations, and higher perceived barriers to vaccination [19]. Nevertheless, because acculturation was assessed as a unidimensional construct, it is impossible to know whether findings were driven by adoption of the host culture, loss of the heritage culture, or some interaction between the two.

The context for the current study was Latina/o parents’ beliefs about vaccination for human papillomavirus (HPV), a common sexually transmitted infection that can cause cancer [24]. HPV vaccination is recommended for all 11 and 12 year-old girls and boys and is effective in preventing HPV infection and reducing HPV-related disease [25]. Nevertheless, rates of HPV vaccine completion in the United Sates are low [25, 26]. Data for the present paper were taken from the baseline assessment of a longitudinal observational study aimed at identifying factors associated with completion of the HPV vaccine series among Hispanic-adolescents [27]. At the time of data collection, series completion was achieved by receipt of three doses over a 6-month period. Currently, adolescents who initiate the HPV vaccine before their 15th birthday need only two doses to complete the series [28].

The present study examined the potentially interactive effects of acculturation and enculturation on parents’ health beliefs about HPV vaccine series completion. Guided by the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Health Belief Model [10, 11], we assessed five health beliefs: perceived threat of HPV infection for their child, and perceived benefits, perceived barriers, subjective norms, and self-efficacy for vaccine series completion. Because knowledge can inform health beliefs [29], we also assessed parents’ HPV-related knowledge. The purpose of this study was to examine how parents’ scores on acculturation, enculturation, and their interaction were associated with their a) knowledge about HPV vaccination and b) health beliefs about their child completing the series. This approach allowed us to assess whether adoption of the host culture, retention of the heritage culture, or some interaction between the two shapes parents’ knowledge and beliefs about protecting their child from HPV infection through vaccination.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

A detailed description of the procedure is available elsewhere [27]. Briefly, caregiver-child dyads (N=161) were recruited from a Federally Qualified Health Center in rural southwest Florida. Because the study was designed to assess factors associated with series completion, we recruited dyads the day the child received the first dose of HPV vaccine (baseline assessment). Additional eligibility criteria for youth included being 11–17 years old, identifying as Hispanic/Latina/o, and being able to read or understand English and/or Spanish. The caregiver accompanying the child had to identify as Hispanic/Latina/o and be able to read or understand English and/or Spanish. All study materials were available in English and Spanish and assessments were conducted in the participant’s preferred language. Caregivers provided informed consent before being interviewed. Data collection took place between July 2014 and May 2016. The study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Acculturation and Enculturation

Acculturation and enculturation were assessed with the 42-item Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale, which has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure [30]. The scale includes three subscales (identity, language competence, cultural competence) each of which are assessed for the host country (United States) and heritage country (i.e., country of origin such as Mexico). U.S./American identity was assessed with six items (“I feel good about being U.S. American” 1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree). Six parallel items assessed ethnic identity (“I feel good about being [Mexican]”). English language competence was assessed with nine items (“How well do you speak English… at school or work?” 1=not at all to 4=extremely well). Nine parallel items assessed Spanish or other native language competence. U.S./American cultural competence was assessed with six items (“How well do you know popular American television shows?” 1=not at all to 4=extremely well). Six parallel items assessed ethnic cultural competence. Means were computed for each subscale. The subscales were then averaged to create two composite scores, representing acquisition of U.S. culture (acculturation; α=.96) and retention of Latina/o culture (enculturation; α=.93), respectively. Composite scores could range from 1.0 to 4.0, with higher values representing greater orientation toward U.S./American and Latina/o culture, respectively. Acculturation and enculturation were uncorrelated, r(132)=.01, p=.90.

Health Beliefs

Items assessing parental health beliefs about their child completing the three-dose HPV vaccine series were adapted from previous research [31] and accompanied by a 4-point response scale (e.g., 1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree). Perceived threat of HPV was assessed as a function of caregivers’ perceptions of the likelihood (“If my child doesn’t get all three HPV vaccine shots, there is a good chance that he/she will get HPV in his/her life”) and seriousness of HPV infection (“HPV infection would be a serious health problem for my child”). Perceived likelihood and seriousness were assessed with two items each. Perceived benefits were assessed with five items reflecting caregivers’ perceived benefits of completing the series (“Getting all three HPV vaccine shots would be good for my child’s health”). Perceived barriers were assessed with three items (“It would be hard for my child to find time to get all three HPV vaccine shots”). To assess subjective norms, we measured caregivers’ perceptions of a) the extent to which other people who are important to them (“referents”) think their child should complete the series (‘normative beliefs’) and b) the extent to which they tend to follow the recommendations of those referents (‘motivations to comply’). Referents included a) the caregiver’s family and b) the child’s health care provider. Normative beliefs were assessed with one item for each referent (“My family would want my child to get all three HPV vaccine shots”). Likewise, motivations to comply were assessed with one item for each referent (“I do what my family thinks I should do”). Self-efficacy to complete the series was assessed with four items (“I feel confident in my ability to get my child all of the HPV vaccine shots even if it is difficult to get my child to the clinic three separate times”).

HPV-Related Knowledge

Knowledge about HPV infection (e.g., “You can have HPV without knowing it”) and vaccination (e.g., “The HPV vaccine helps protect against cervical cancer”) was assessed with ten and five true/false items, respectively, adapted from previous research [23]. Participants were asked to respond “don’t know” if they were not sure of the correct answer.

Analysis

To compute scale scores for perceived benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy, we averaged the items for each construct. To compute a perceived threat scale score, we averaged the perceived likelihood items and the perceived seriousness items, and then computed the product of those two scores [11]. To compute a subjective norms scale score, we multiplied ‘normative beliefs’ by ‘motivations to comply’ for each referent and then took the average of the two products. Composite scores for each knowledge domain (HPV infection and vaccination) were computed by assigning one point for each correct response. Participants who had never heard of HPV or HPV vaccination received a score of zero on the respective domain. A total knowledge score was computed by summing the two domain scores.

Descriptive statistics were computed for caregiver and child sociodemographic and background characteristics, caregiver acculturation and enculturation, and the six primary outcome variables (health beliefs and HPV-related knowledge; See Tables 1 and 2). To provide an initial conservative test that takes into account correlations among outcome variables, we performed one multivariate regression analysis in which all six outcome variables were simultaneously predicted from acculturation, enculturation, and their interaction (the product of the centered acculturation and enculturation scores), while controlling for caregiver sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., centered age, gender, education, income, and insurance status). We then conducted a series of independent multiple regression analyses in which each outcome variable was predicted from caregiver acculturation, enculturation, and their interaction, while controlling for caregiver sociodemographic characteristics. For each predictor, we report the unstandardized regression coefficient, standard error, standardized regression coefficient, and semi-partial correlation (Table 3). If a statistically significant interaction was observed, we examined the effect of enculturation on the outcome at high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1 SD below the mean) levels of acculturation while controlling for sociodemographics [32]. Reported p-values are not adjusted for multiplicity.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Background Characteristics for Caregivers (CG) and their Children

| N (%) or Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Caregiver (CG) Characteristics | |

| CGage in years | 37.84 (6.33) |

| C Grace | |

| Other or unknowna | 131 (81) |

| White | 30(19) |

| CG gender | |

| Male | 4(3) |

| Female | 157 (98) |

| CG is child’s mother | |

| No | 7(4) |

| Yes | 154 (96) |

| CG education | |

| No formal education | 18(11) |

| Some elementary school | 65 (41) |

| Some middle school | 31 (19) |

| Some high school | 22(14) |

| High school graduate or GED | 7(4) |

| Vocational school or AA degree | 8(5) |

| Some college | 6(4) |

| College degree | 3(2) |

| CG health insurance | |

| None | 124 (78) |

| Public or private insurance | 35 (22) |

| CG relationship status | |

| Married | 79 (49) |

| Living with partner | 49 (30) |

| Divorced | 10(6) |

| Single | 23 (14) |

| CGborn in U.S. | |

| No | 136(85) |

| Yes | 25 (16) |

| CG region of birthb | |

| Mexico | 96 (60) |

| Central America | 37 (23) |

| Other (e.g., Cuba) | 3(2) |

| Number of years in U.S.b | 18.01 (6.76) |

| CG interview language | |

| Spanish | 128 (80) |

| English or English & Spanish | 33 (21) |

| Migrant farm work | |

| Entire family | 37 (23) |

| Parent and/or other member | 34(21) |

| No one in family | 88 (55) |

| Child Characteristics | |

| Child age at first dose | 11.82(1.58) |

| Child racea | |

| Other or unknown | 134 (83) |

| White | 27(17) |

| Child gender | |

| Male | 86 (53) |

| Female | 75(47) |

| Child eligible for free school mealsc | |

| No | 2(1) |

| Yes | 139(86) |

| Unknown | 20(12) |

| Child health insurance | |

| None | 10(6) |

| Public or private insurance | 150(94) |

| Child born in U.S. | |

| No | 5(3) |

| Yes | 156 (97) |

Most participants described their race and their daughter or son’s race as “Hispanic” or “Latina/o.” Such responses were coded as “unknown.”

Assessed among foreign-born caregivers only.

20 participants are missing a response to this question because it was added to the interview after data collection had already begun. This variable was used as a proxy for family income.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Caregiver Acculturation, Enculturation, Knowledge, and Health Beliefs

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Acculturationa | 2.31 (0.75) |

| Enculturationa | 3.20 (0.46) |

| HPV-related knowledgeb | 5.01 (4.36) |

| Perceived threatc | 11.15 (4.26) |

| Perceived benefitsa | 3.79 (0.33) |

| Perceived barriersa | 1.69 (0.73) |

| Subjective normsc | 12.43 (3.23) |

| Self-efficacya | 3.83 (0.33) |

Note. SD = standard deviation.

Scores could range from 1–4 with higher values indicating more endorsement.

Scores could range from 1–15 with higher values indicating higher knowledge.

Scores could range from 1–16 with higher values indicating more endorsement.

Table 3.

Results from Regression Analyses Predicting Caregiver Knowledge and Health Beliefs while Controlling for Caregiver Age, Gender, Education, Income, and Health Insurance

| Age b (SE) β(r) |

Gender b (SE) β(r) |

Education b (SE) β(r) |

Income b (SE) β(r) |

Insurance b (SE) β(r) |

Acculturation b (SE) β(r) |

Enculturation b (SE) β(r) |

A x E Interactiona b (SE) β(r) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | −.00 (.05) | −1.24(1.96) | .68* (.27) | 3.71 (2.71) | 2.81* (.97) | −.13 (.61) | 2.44* (.78) | −2.55* (1.00) |

| −.01 (−.01) | −.05 (−.05) | .27 (.21) | .11 (.11) | .28 (.23) | −.02 (−.02) | .26 (.25) | −.21 (−.21) | |

| Perceived threat | −.04 (.07) | .70 (2.33) | −.05 (.34) | −1.89(3.21) | 2.15(1.21) | −.51 (.77) | .99(1.00) | −.30(1.33) |

| −.07 (−.07) | .03 (.03) | −.02 (−.02) | −.06 (−.06) | .20 (.18) | −.09 (−.07) | .10 (.10) | −.02 (−.02) | |

| Perceived benefits | .01 (.01) | −.01 (.17) | .00 (.02) | −.26 (.23) | −.17* (.08) | .13* (.06) | .12 (.07) | −.18* (.09) |

| .10 (.09) | −.00 (−.00) | .02 (.01) | −.10 (−.10) | −.22 (−.19) | .29 (.22) | .16 (15) | −.19 (−.18) | |

| Perceived barriers | .01 (.01) | −.13 (.36) | −.05 (.05) | −.53 (.50) | −.34 (.18) | −.13 (.11) | −.26 (.14) | .36* (.18) |

| .08 (.08) | −.03 (−.03) | −.12 (−.09) | −.10 (−.09) | −.20 (−.17) | −.13 (−.10) | −.16 (−.16) | .18 (.17) | |

| Subjective norms | .00 (.05) | −.11 (1.66) | −.03 (.23) | −1.09 (2.29) | −1.58 (.82) | .39 (.52) | .92 (.67) | −.92 (.86) |

| .00 (.00) | −.01 (−.01) | −.02 (−.01) | −.05 (−.05) | −.22 (−.18) | .10 (.07) | .13 (.13) | −.11 (−.10) | |

| Self-efficacy | −.00 (.01) | −.09 (.17) | .05* (.02) | −.08 (.23) | .01 (.08) | .01 (.05) | .16* (.07) | −.25** (.09) |

| −.06 (−.06) | −.05 (−.05) | .24 (.19) | −.03 (−.03) | .01 (.01) | .02 (.01) | .22 (.22) | −.27 (−.26) |

Note. For each predictor variable we report the following statistics: Upper row: Unstandardized regression coefficient (b) and standardized error (SE) in parentheses. Lower row: Standardized regression coefficient (β) and the semi-partial correlation (r) in parentheses (a measure of effect size). Variables were coded as follows: Gender: 1 = Male; 2 = Female; Income: 0 = Child not eligible for free or reduced price school meals; 1 = Child eligible for free or reduced price school meals; Insurance: 0 = No insurance; 1 = Private or Public insurance. Age and education were treated as continuous variables.

Acculturation by Enculturation Interaction

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

Results

Sample Characteristics

On average, caregivers were 38 years old and most (96%) were the child’s mother. Eleven percent reported having no formal education and nearly 80% had no health insurance. The large majority were born in Mexico or Guatemala and responded to the interview in Spanish. Most youth were 11 years old when they received the first dose of HPV vaccine. The sample included slightly more male (53%) than female children. The large majority of children received public health insurance and were eligible for free school meals. About 45% had at least one family member engaged in migrant farm work. See Table 1 for additional details.

Multivariate Regression Analysis

In addition to main effects of caregiver insurance, F(6,84)=3.15, p=.008, and Latina/o enculturation, F(6,84)=2.43, p=.033, we observed a statistically significant interaction between acculturation and enculturation, F(6,84)=2.47, p=030. No other statistically significant effects were observed.

Independent Multiple Regression Analyses

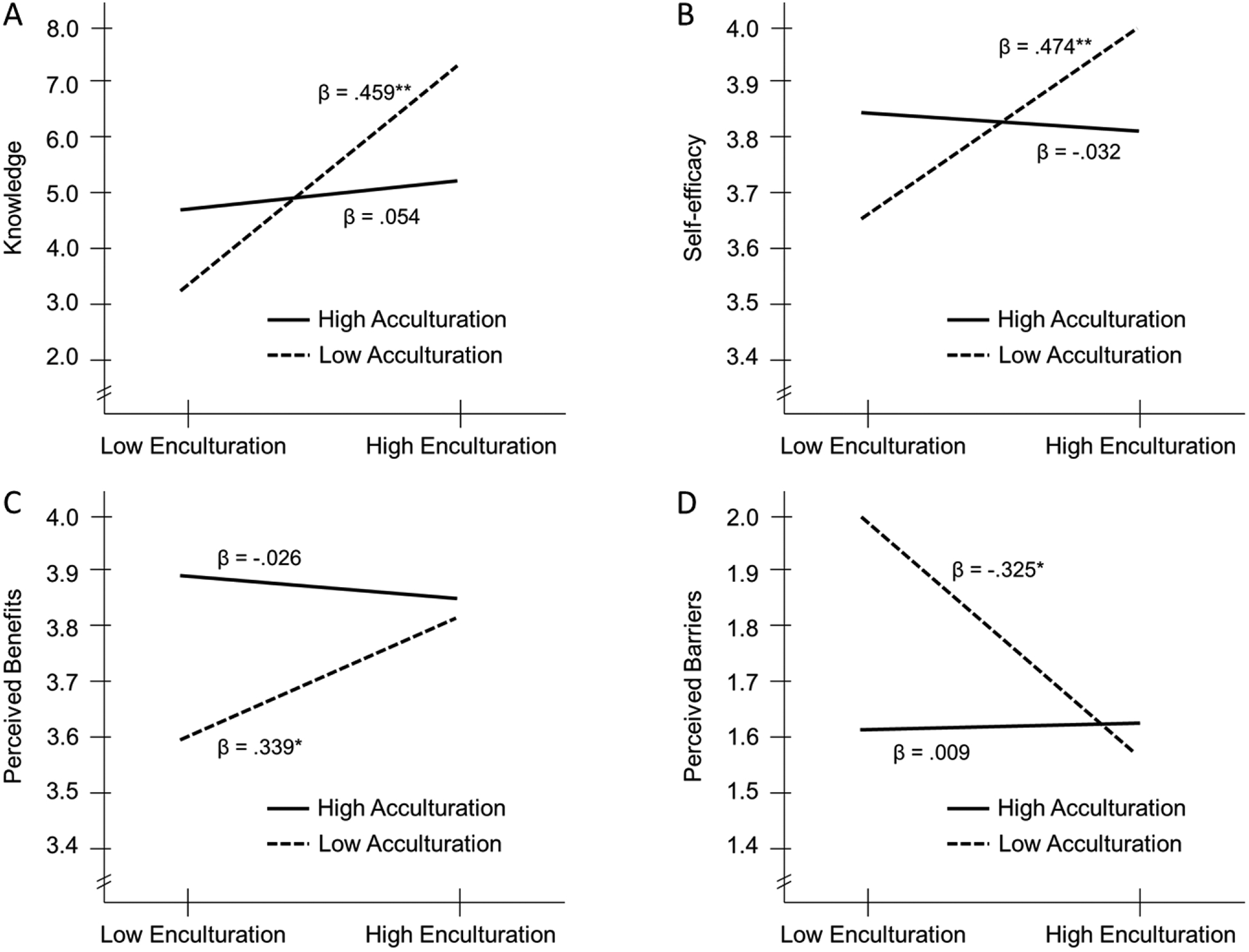

A statistically significant interaction between acculturation and enculturation was observed for four of the six outcome variables: HPV-related knowledge, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy (Table 3). No effects of acculturation, enculturation, or their interaction were observed for perceived threat or subjective norms. Although the direction of the interaction effect differed depending on the nature of the outcome variable, the meaning of the interaction was consistent across the four outcome variables (Figure 1). When acculturation was high, caregivers tended to have relatively high knowledge and favorable beliefs about HPV vaccine completion, regardless of their score on enculturation. That is, enculturation (retention of heritage culture) was not associated with HPV-related knowledge, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, or self-efficacy among caregivers who scored relatively high on acculturation. However, when acculturation was low, enculturation was related to both knowledge and health beliefs such that caregivers who scored higher on enculturation tended to have higher knowledge and more favorable beliefs than caregivers who scored lower on enculturation.

Figure 1.

Effects of acculturation, enculturation, and their interaction on caregivers’ HPV-related knowledge and health beliefs associated with their child completing the 3-dose HPV vaccine series, controlling for caregiver sociodemographics. Panel A: HPV-related Knowledge. Panel B: Self-efficacy. Panel C: Perceived Benefits. Panel D: Perceived Barriers. For all four outcome variables we observed an interaction between acculturation and enculturation such that caregivers who acquired more U.S. culture (i.e., scored relatively high on acculturation) reported higher knowledge and more favorable health beliefs associated with series completion regardless of their score on enculturation. However, among caregivers who acquired less U.S. culture (i.e., scored relatively low on acculturation), those with higher (vs. lower) enculturation scores reported higher knowledge and more favorable health beliefs about series completion. Standardized regression coefficients from the simple effects tests are reported. **p ≤ .001. * p ≤ .01.

See Figure 1 for the acculturation by enculturation interaction for each of the four outcome variables. Consider, for example, the pattern for self-efficacy (Panel B, Figure 1). When acculturation was high, enculturation had little effect on self-efficacy; levels of self-efficacy were favorable among caregivers who had acquired more U.S. culture regardless of the extent to which they had retained their heritage culture. However, when acculturation was low, enculturation was positively associated with self-efficacy such that caregivers who scored higher (vs. lower) on enculturation also reported higher self-efficacy. Caregivers who scored low on acculturation but high on enculturation demonstrated levels of self-efficacy for series completion that were similar to caregivers with high acculturation scores. The lowest levels of self-efficacy were observed among caregivers with low scores on both acculturation and enculturation.

Discussion

In evaluating the relationship between culture and health beliefs, the present study advances the literature by underscoring the importance of independently assessing acculturation and enculturation. We observed interactive effects of acculturation and enculturation for four outcome measures associated with HPV vaccine series completion while controlling for caregiver sociodemographic characteristics. Caregivers who had adopted U.S. culture (i.e., had high acculturation scores) were more knowledgeable and held more favorable health beliefs about series completion, regardless of the extent to which they retained their heritage culture. However, among caregivers who had not adopted U.S. culture, the extent to which they retained their heritage culture was of importance. Higher knowledge and more favorable health beliefs were observed among caregivers who had largely retained their heritage culture, as compared to those who had not. Caregivers scoring low on both enculturation and acculturation tended to be the least knowledgeable and held the least favorable health beliefs about their child completing the series. Rates of HPV vaccine completion are currently higher among Latina/o adolescents (57%) than non-Hispanic white adolescents (48%) [26], yet little research has investigated what might account for this difference. The current findings begin to provide some insight into this issue and highlight the benefits of considering both host culture acquisition and heritage culture retention when examining health-related outcomes in immigrant populations.

Favorable HPV knowledge and beliefs among those with high acculturation scores could be explained by the fact that such individuals tend to display high engagement with the health care system, particularly preventive health services [2]. In such individuals, retention of their heritage culture may exhibit little additional benefit over and above their already high levels of engagement. But what might explain the positive relationship between enculturation and support for HPV vaccination among caregivers who had not adopted U.S. cultural practices? Exposure to robust immunization programs in their countries of origin provides one possible explanation. In the early 1980s Mexico implemented a highly successful immunization program that resulted in large decreases in child mortality [33, 34]. Continued support for childhood immunization is evident in Mexico’s nationwide school-based HPV vaccine program [35]. Studies also suggest high acceptance of childhood vaccination-including HPV vaccination-among Latin American parents [22, 36, 37] and Latina/o immigrants living in the United States [16–22]. In sum, enthusiastic support for HPV vaccine completion among caregivers with high enculturation and low acculturation may stem in large part from the strong commitment to childhood immunization in their native countries.

The lowest levels of knowledge and least favorable beliefs about HPV vaccine completion were observed among caregivers scoring relatively low on both acculturation and enculturation. These participants may reflect Berry’s [14] concept of “marginalization” in the sense that they may not identify strongly with - or even actively reject - aspects of their host and heritage cultures. Scholars have argued that culturally marginalized individuals may experience “cultural identity confusion,” which can undermine active engagement with either culture [38, 39]. Marginalization could also be a strategy for dealing with acculturative stress or a response to perceived discrimination or rejection from the host culture. Although 37% of the current sample scored below 2.0 on acculturation (indicating lack of engagement with U.S. culture), none had an enculturation score below 2.0 and only 10% scored below 2.5. This suggests that even those caregivers who scored relatively low on enculturation retained at least some elements of their heritage culture. It will be important for future research to identify effective intervention strategies for empowering this group that may be “in between” or confused about their cultural identity, as they may miss out on important opportunities to protect their child’s health.

Study limitations provide important directions for future research. First, findings are limited to HPV vaccination and thus may not generalize to other health behaviors. Second, although perceived threat, benefits and barriers, subjective norms, and self-efficacy represent core constructs from central theories of health behavior, they may not capture the full range of health beliefs important to different cultural groups. Third, the sample was limited to Latino/a caregivers, most of whom had emigrated from Mexico and Guatemala. Future research should examine joint effects of acculturation and enculturation for other immigrant groups in the United States. Finally, all caregivers in the present study allowed their child to receive the first dose of HPV vaccine and thus may view HPV vaccination more favorably than caregivers with children who have not initiated the series.

In sum, acculturation and enculturation interacted to predict Latina/o parents’ knowledge and beliefs about HPV vaccination. Findings suggest that failing to account for heritage culture retention may lead to incomplete conclusions about the relationship between acculturation and health. The current findings have important implications for the development of interventions promoting HPV vaccine series completion among Latina/o adolescents and for the broader literature on acculturation and health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the health care providers and staff in the Pediatrics Clinic in Immokalee, FL for their assistance with this study. We are also indebted to the many families who contributed to this project. This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R21CA178592. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Contributor Information

Mary A. Gerend, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Social Medicine, College of Medicine, Florida State University (FSU), Tallahassee, FL; Dr. Gerend was on the faculty at Northwestern University, Chicago, IL when portions of this research were conducted.

Yesenia P. Stephens, College of Medicine, FSU, Tallahassee, FL.

Michelle M. Kazmer, School of Information, College of Communication and Information, FSU, Tallahassee, FL.

Elizabeth H. Slate, Department of Statistics, College of Arts & Sciences, FSU, Tallahassee, FL.

Elena Reyes, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Social Medicine, College of Medicine, FSU, Tallahassee, FL..

References

- [1].Abraido-Lanza AF, Echeverria SE, Florez KR. Latino immigrants, acculturation, and health: Promising new directions in research. Ann Rev Public Health 2016;37:219–36. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, et al. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Ann Rev Public Health 2005;26:367–97. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Salant T, Lauderdale DS. Measuring culture: a critical review of acculturation and health in Asian immigrant populations. Soc Sci Med 2003;57(1):71–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yoon E, Chang CT, Kim S, et al. A meta-analysis of acculturation/enculturation and mental health. J Couns Psychol 2013;60(1):15–30. DOI: 10.1037/a0030652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. Am Psychol 2010;65(4):237–51. DOI: 10.1037/a0019330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ayala GX, Baquero B, Klinger S. A systematic review of the relationship between acculturation and diet among Latinos in the United States: implications for future research. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108(8):1330–44. DOI: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Delavari M, Sonderlund AL, Swinburn B, et al. Acculturation and obesity among migrant populations in high income countries--a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013;13:458 DOI: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Park J, Myers D, Kao D, Min S. Immigrant obesity and unhealthy assimilation: alternative estimates of convergence or divergence, 1995–2005. Soc Sci Med 2009;69(11):1625–33. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schwartz SJ, Unger JB. Acculturation and health: State of the field and recommended directions In: Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, editors. The Oxford handbook of acculturation and health New York: NY: Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr 1974;2:328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Abraido-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Florez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. Am J Public Health 2006;96(8):1342–6. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gordon M. Assimilation in American life. New York: NY: Oxford University Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Berry JW. Conceptual approaches to understanding acculturation In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. p. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fox M, Thayer Z, Wadhwa PD. Assessment of acculturation in minority health research. Soc Sci Med 2017;176:123–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Constantine NA, Jerman P. Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination among Californian parents of daughters: a representative statewide analysis. J Adolesc Health 2007;40(2):108–15. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Luque JS, Castaneda H, Tyson DM, et al. Formative research on HPV vaccine acceptability among Latina farmworkers. Health Promot Prac 2012;13(5):617–25. DOI: 10.1177/1524839911414413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Luque JS, Raychowdhury S, Weaver M. Health care provider challenges for reaching Hispanic immigrants with HPV vaccination in rural Georgia. Rural Remote Health 2012;12(2):1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Prislin R, Suarez L, Simpson DM, Dyer JA. When acculturation hurts: the case of immunization. Soc Sci Med 1998;47(12):1947–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sanderson M, Coker AL, Eggleston KS, et al. HPV vaccine acceptance among Latina mothers by HPV status. J Womens Health 2009;18(11):1793–9. DOI: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Scarinci IC, Garces-Palacio IC, Partridge EE. An examination of acceptability of HPV vaccination among African American women and Latina immigrants. J Womens Health 2007;16(8):1224–33. DOI: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wentzell E, Flores YN, Salmeron J, Bastani R. Factors influencing Mexican women’s decisions to vaccinate daughters against HPV in the United States and Mexico. Family and Community Health 2016;39(4):310–9. DOI: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gerend MA, Zapata C, Reyes E. Predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among daughters of low-income Latina mothers: the role of acculturation. J Adolesc Health 2013;53(5):623–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recommendations and Reports 2014;63(RR-05):1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Markowitz LE, Gee J, Chesson H, Stokley S. Ten years of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United States. Acad Pediatr 2018;18(2S):S3–S10. DOI: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68(33):718–23. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gerend MA, Stephens YP, Kazmer MM, et al. Predictors of human papillomavirus vaccine completion among low-income Latina/o adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2019;64(6):753–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-Dose Schedule for Human Papillomavirus Vaccination - Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2016;65(49):1405–8. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fishbein M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Commun Theor 2003;13(2):164–83. DOI: DOI 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00287.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zea MC, Asner-Self KK, Birman D, Buki LP. The abbreviated multidimensional acculturation scale: empirical validation with two Latino/Latina samples. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2003;9(2):107–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mullins TL, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, et al. Adolescent perceptions of risk and need for safer sexual behaviors after first human papillomavirus vaccination. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166(1):82–8. DOI: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Frenk J, Sepulveda J, Gomez-Dantes O, Knaul F. Evidence-based health policy: three generations of reform in Mexico. Lancet 2003;362(9396):1667–71. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14803-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mexico’s immunization programme gets results. CVI Forum 1994(6):4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward implementation of human papillomavirus vaccination--the Americas, 2006–2010. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2011;60(40):1382–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lazcano-Ponce E, Rivera L, Arillo-Santillan E, et al. Acceptability of a human papillomavirus (HPV) trial vaccine among mothers of adolescents in Cuernavaca, Mexico. Arch Med Res 2001;32(3):243–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lee FH, Paz-Soldan VA, Carcamo C, Garcia PJ. Knowledge and attitudes of adult peruvian women vis-a-vis Human Papillomavirus (HPV), cervical cancer, and the HPV vaccine. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2010;14(2):113–7. DOI: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3181c08f5e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Berry JW, Kim U. Acculturation and mental health In: Dasen P, Berry JW, Sartorius N, editors. Health and cross-cultural psychology London: Sage; 1988. p. 207–36. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL. Testing Berry’s model of acculturation: a confirmatory latent class approach. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2008;14(4):275–85. DOI: 10.1037/a0012818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]