Abstract

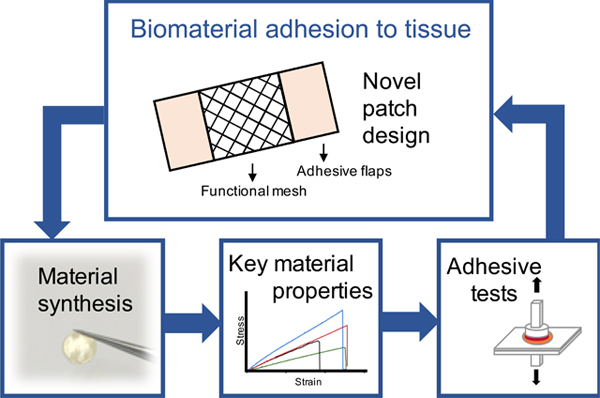

In order to secure biomaterials to tissue surfaces, sutures or glues are commonly used. Of interest is the development of a biomaterial patch for applications in tissue engineering and regeneration that incorporates an adhesive component to simplify patch application and ensure sufficient adhesion. A separate region dedicated to fulfilling the specific requirements of an application such as mechanical support or tissue delivery is also desirable. Here, we present the design and fabrication of a unique patch with distinct regions for adhesion and function, resulting in a biomaterial patch resembling the Band-Aid. The adhesive region contains a novel polymer which we synthesized to incorporate a molecule capable of adhesion to tissue, dopamine. The desired polymer composition for patch development was selected based on chemical assessment and evaluation of key physical properties such as swelling and elastic modulus, which were tailored for use in soft tissue applications. The selected polymer formulation, referred to as the adhesive patch (AP) polymer, demonstrated negligible cytotoxicity and improved adhesive capability to rat cardiac tissue compared to currently used patch materials. Finally, the AP polymer was used in our patch, designed to possess distinct adhesive and non-adhesive domains, presenting a novel design for the next generation of biomaterials.

Keywords: Biomaterials, polymers, patch adhesion, soft tissue, elasticity, patterning, microfabrication

Table of Contents Text

A biomaterial patch that incorporates an adhesive component was designed to address an unmet need in patch technology - patch adhesion. A novel polymer containing dopamine was synthesized and a favourable composition was selected based on key chemical and physical properties. This material demonstrated improved adhesion to tissue and was used in the fabrication of a dual-component patch designed to possess distinct regions for adhesion and function.

1. Introduction

The Band-Aid is a familiar biomedical material that contains several regions designed to perform specific tasks. A barrier region provides a protected or moist environment for healing or for delivery of a therapeutic and two adhesive flaps ensure secure attachment. While this design is very effective, its application is limited to wound healing wherein the material is applied on the surface of the body.

There are, however, a wide range of other medical procedures and applications that require biomedical fixatives such as drug delivery [1], tissue repair and reconnection [2, 3], and device attachment and engraftment [4]. Sutures and staples have been commonly used, especially in surgical procedures, however they suffer from significant limitations. They pierce the surrounding tissue, which can lead to tissue damage and inflammation, and they are time-consuming and challenging to apply, especially in difficult to reach areas [5] – a common recent occurrence given the increase in the number of minimally invasive procedures performed annually [6]. Because of these limitations, there has been a shift towards the use of sealants, designed to generate fluid or air-tight closures, and adhesives, which are used to bind tissue. However, many currently available sealants and adhesives are rigid [7], causing issues especially when used in challenging, dynamic environments such as contracting tissues and organs.

More recently, biomedical applications such as tissue engineering and regeneration, in which biomaterials are used to deliver tissue, cells, bioactive elements, or provide mechanical support to restore function or encourage regeneration, have been established. In these cases, biomaterials must be adequately confined or secured to a desired location. However, these materials often exist as a uniform material, even though the functional requirement of sufficient adhesion may exist. Therefore, it is conceivable that the development of a biomaterial system resembling the Band-Aid would be highly useful due to its ease of application and ability to adhere to sites, while still providing space for its other intended function, such as cell growth. Furthermore, if its mechanical properties are tuned to match native tissue, it could address issues that arise with currently available rigid fixatives. One application for which this design would be highly applicable is in scaffolds for soft tissue engineering.

Here, we describe the design and fabrication of a patch that can be used in biomedical applications where mechanical support or tissue delivery via a patch, as well as adhesion to tissue, is required. We designed a patch which is comprised of two elements: a centre scaffold mesh domain, and two outer adhesive flaps. In order to do this, we required a material that could adhere to tissue surfaces and also be fabricated into a patch of specific geometry. We required a biomaterial that can adhere to tissue surfaces relatively rapidly and in a wet environment and that maintains elastic properties matching those of soft tissues, such as for example the myocardium. We hypothesized that we could make a material with both elastic and adhesive properties, that is also moldable and photocrosslinkable to enable fabrication into a patch of precise geometry controlled at the micron-scale. Specifically, we aimed to develop citrate-based polymers containing dopamine, an amine-derivative of the L-DOPA molecule described for use as a surgical adhesive material [8].

In this work, we selected a desirable adhesive patch material based on chemical assessment and evaluation of key physical properties. We matched the mechanical properties (i.e. elastic modulus) of the polymer patch to that of native cardiac tissue, an example of a soft tissue that would benefit from this scaffold technology, and then tested the adhesive properties and cytotoxicity of the patch. This material was then used in the patch consisting of spatially varied regions of adhesion with our novel polymer acting as an adhesive component, as well as a distinct region that can contain an alternative composition which can be tuned for the intended function and application. To achieve this, we focused on micromolding, using perfusion of two polymers through a mold to form a uniform patch with regions of adhesive polymer flaps and scaffold mesh. To the best of our knowledge, no adhesive biomaterial patch utilizing this design currently exists.

2. Results

2.1. Chemical characterization

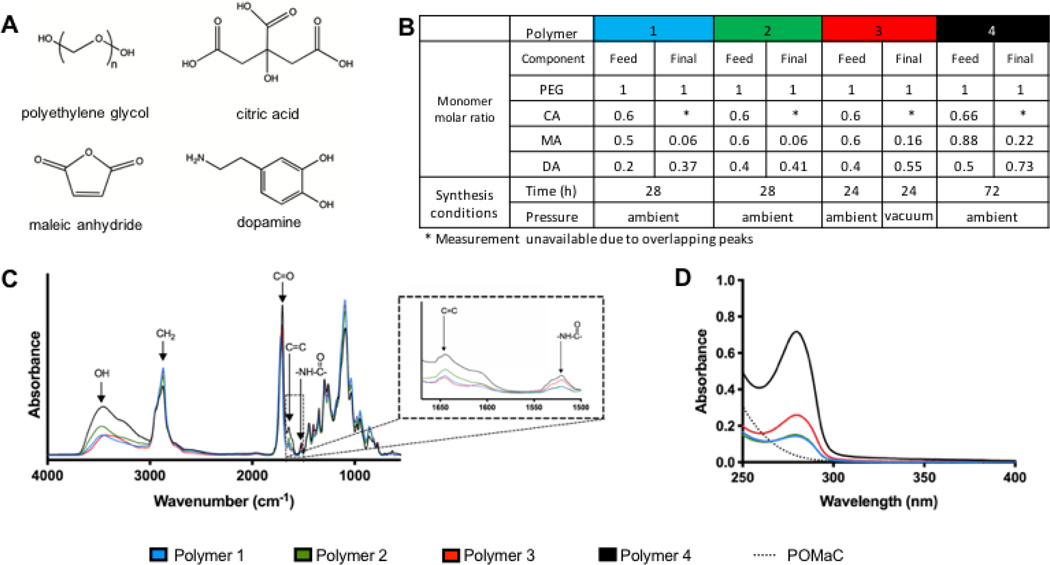

Pre-polymers were synthesized in a reaction between citric acid (CA), polyethylene glycol (PEG), maleic anhydride (MA) and dopamine (DA) (Figure 1A). Polymers of two compositions (Table 1 composition A and B) were synthesized by reacting monomers for the same amount of time (Table 2 condition X). For compositions A and B, the ratio of maleic anhydride to PEG was selected and the amount of dopamine was then calculated to maintain equal ratios of total carboxylic acid groups to total alcohol and amine groups. These two compositions are denoted as polymer 1 and polymer 2 respectively. Analysis of the incorporation of specific monomers completed through integration of 1H NMR peaks associated with those monomers (Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure 1) revealed that the ratio of MA incorporated into the final polymer was low for all of the tested compositions. We sought to increase the reaction of this monomer, thereby also potentially furthering reaction of other monomers as well, by increasing reaction time and introducing a reduction in pressure. This was accomplished by reacting compositions A and B for 24 hours at ambient pressure and 24 hours under vacuum (Table 2 condition Y). Composition A under condition Y resulted in a solid material and was therefore not assessed further, as it could not be used for our application. As evidenced by the 1H NMR analysis, increased integration of MA as well as dopamine was achieved for the polymer synthesized with composition B under condition Y, denoted as polymer 3.

Figure 1. Polymer synthesis conditions and chemical characterization.

A) Chemical structure of monomers. B) Polymer composition and synthesis conditions. Molar ratio of monomers in the initial feed and the molar ratio of monomers determined by 1H NMR analysis of the final product are indicated. C) ATR-FTIR spectra of pre-polymers. D) UV-visible spectrum of pre-polymers.

Table 1.

Ratio of monomers

| Mol ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition | PEG | CA | MA | DA |

| A | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.20 |

| B | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| C | 1.00 | 0.66 | 0.88 | 0.50 |

Table 2.

Reaction conditions

| Condition | Time [h] | Pressure |

|---|---|---|

| X | 28 | ambient |

| Y | 24 | ambient |

| then 24 | vacuum | |

| Z | 72 | ambient |

FTIR confirmed the presence of characteristic functional groups (Figure 1C). The peaks at 1532 cm−1 were assigned to amide groups, which are attributed to the incorporation of dopamine in the polymer. The peaks at 1648 cm−1 were assigned to the carbon-carbon double bond that is present in maleic anhydride. Peaks around 1720 cm−1 were assigned to carbonyl groups and the peaks in the 2860–2935 cm−1 range were assigned to methylene groups. Finally, the peaks around 3500 cm−1 were assigned to hydroxyl groups. The presence of dopamine in the purified pre-polymer solution was further confirmed using UV-visible spectroscopy (Figure 1D). The demonstration of UV light absorption at 280 nm wavelength is characteristic of the unoxidized catechol structure in dopamine [8]. The observed increased dopamine content in polymer 3 (1H NMR) is also seen in the UV-vis spectra.

Since the incorporation of the dopamine molecule was carried out to include an adhesive moiety in the polymer, we sought to increase the dopamine content further, to achieve more potential for adhesion. The ratio of dopamine was increased to 0.5 of the relative PEG molar content, and we incorporated excess total acid content to facilitate its incorporation (Table 1 composition C). MA feed content was increased due to its low incorporation, which we attribute to the need for ring opening reactivity. Furthermore, reaction time was increased (Table 2 condition Z). Chemical analysis of the resulting polymer, polymer 4, indicated a higher dopamine content, as demonstrated through FTIR, 1H NMR and UV-vis analysis. Furthermore, the MA content was also assessed to be higher, and this is shown by both 1H NMR analysis and in carbon-carbon double bond peak in the FTIR spectra.

2.2. Physical characterization

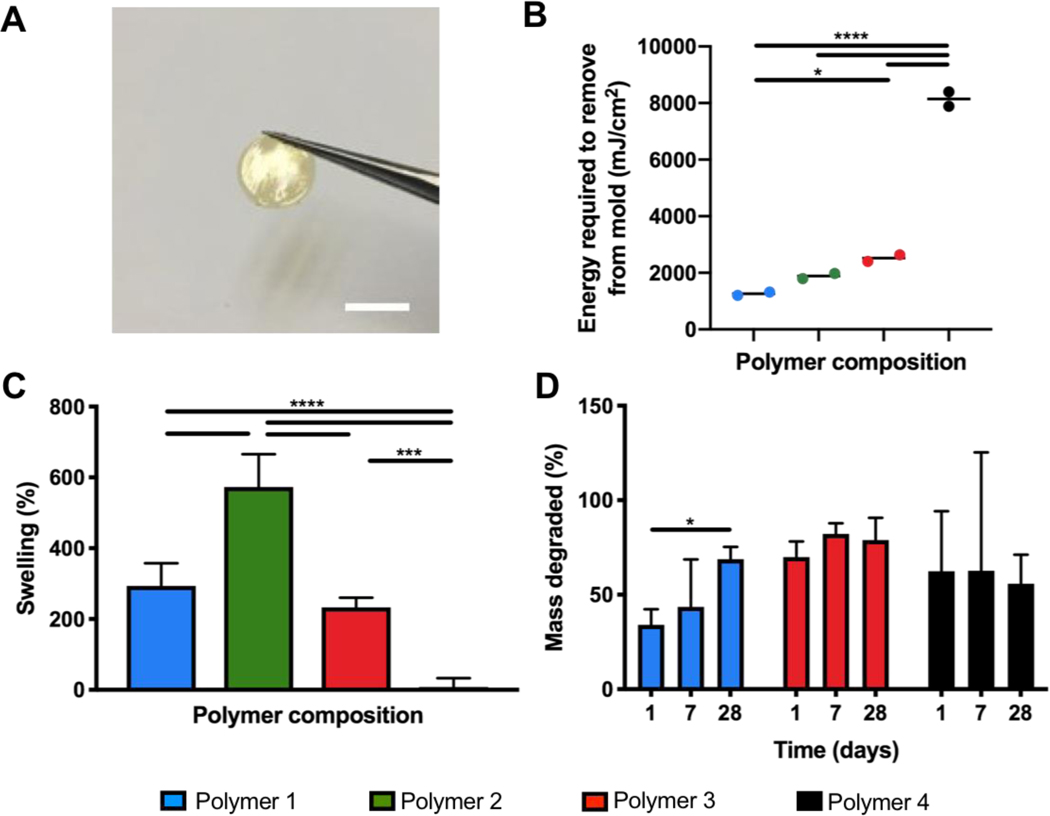

The pre-polymers were easily fabricated into solid films using photocrosslinking of the double bonds present in the polymer chain as a result of the MA incorporation. After exposure to UV light with a photoinitiator, the polymer could be handled in film format (Figure 2A). The UV energy required to generate solid films that could be removed from their molds was evaluated (Figure 2B). Although polymer 4 had a higher ratio of MA than the other polymer compositions, the energy required to generate a solid film was notably higher. Crosslinking behavior can be impacted by a number of factors, including polymer branching, molecular weight, and esterification of molecular groups containing unsaturated bonds [9]. In addition, dopamine is a known antioxidant, and the increased content in polymer 4 may inhibit the efficiency of radical propagation in a more significant manor than heightened MA integration [10]. Given the application that we are interested in using this material in, the UV crosslinking process occurs as a processing step, and a higher energy requirement to crosslink is not an inhibitory factor for selecting this particular polymer composition.

Figure 2. Physical characterization of crosslinked polymers.

A) Crosslinked polymer film (scale bar = 5mm). B) UV crosslinking energy required to form solid film (n=2). C) Percent swelling in water for polymer films crosslinked with UV energy: Polymer 1–3 = 2500 mJ cm−2, Polymer 4 = 7200 mJ cm−2. (n=5). D) Degradation of crosslinked polymers in PBS (n=3 to 5). Significant differences from one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test are defined as *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Swelling test measurements indicated that all but one of the polymer compositions generated in this work swelled to over 200% of their initial volume (Figure 2C). Because PEG, a very hydrophilic polymer, is a significant component of this polymer, a high degree of swelling is understood by its presence in the polymer chain, allowing water to penetrate and surround the polymer network. Polymer 4, which possessed a relatively lower ratio of PEG than all other polymer compositions, demonstrated significantly lower swelling capacity as well, with no swelling observed. While the feed ratios indicate that polymer 2 has a relatively lower PEG content than polymer 1, the final ratios excluding CA are quite close between these two compositions. Differences in monomer feed ratios is likely to result in differences in chain branching and varying polymer fragments, some of which are shown in Supplemental Figure 2. These differences can alter the overall properties of the polymers. Furthermore, swelling also relates to crosslinking behaviour, which varied between the compositions. While for application as a soft tissue scaffold we require a material that retains its shape and precise dimensions, a bulking material could be useful to a certain extent in applications such as cardiac tissue engineering as it could ultimately help preserve the structure of the ventricle wall that experiences substantial thinning after myocardial infarction.

Polymers demonstrated rapid mass loss upon exposure to solution, as uncrosslinked polymer chains are washed from the film (Figure 2D). Notable degradation in PBS was observed after one day, following which degradation slowed. Of the compositions assessed, only one, polymer 1, continued to show a reduction in mass after a period of four weeks. For the other two selected compositions (polymer 3 and 4) insignificant degradation was observed after one week.

2.3. Mechanical properties

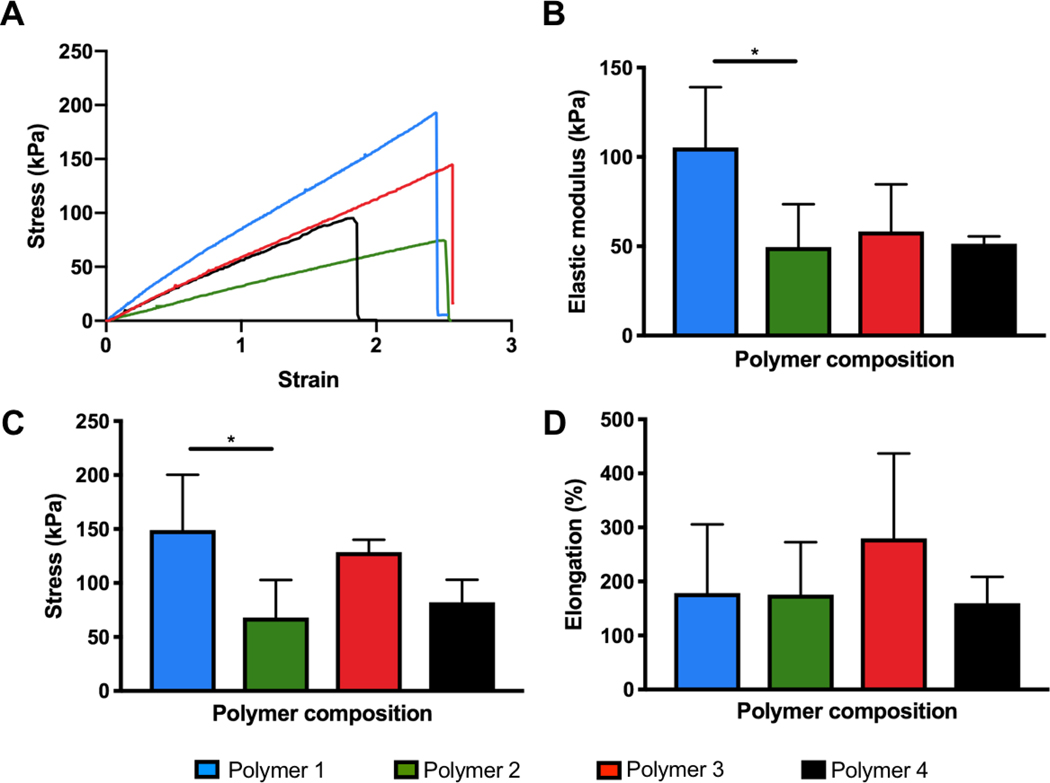

Mechanical properties were assessed through tensile testing. Strips of polymer 1, 2 and 3 were crosslinked using 2500 mJ cm−2 of UV energy while polymer 4 was crosslinked at 7200 mJ cm−2 UV energy. These energies were selected based on values near the measured energies required to generate a solid film easily removable from the mold.

Results demonstrate that all of the polymer compositions produced films with elastic properties (Figure 3). Like swelling ratio and UV energy required to crosslink, significant differences exist between polymer 1 and 2 in terms of elastic modulus and ultimate tensile strength, despite having similarities in final feed composition. The difference in composition resulting in the different mechanical properties could be due to polymer chain branching occurring at different junctions and to varying extents, resulting in overall different mechanical properties. Additionally, we observed that the UV energy required to generate a stable film is slightly different between these two polymers, indicating that polymer 1 crosslinks with less energy. This supports the idea that even though the composition of these two polymers may be similar, the arrangement of polymer chains is likely different. Polymer 2, 3 and 4 exhibited an elastic modulus closely matching the native rat myocardium, which is around 43 ± 9 kPa in the long direction [11]. Elongation at break greatly surpassed the strain that one could expect physiologically in vivo, and therefore it and failure stress were not considered to be critical properties for selection of our polymer composition. These tests were performed in dry conditions.

Figure 3. Mechanical properties of crosslinked polymers under dry conditions.

A) Representative stress-strain curves. B) Elastic modulus. C) Ultimate tensile strength. D) Elongation at break. Polymers 1–3 were crosslinked with 2500 mJ cm−2 UV energy (n=5) and polymer 4 was crosslinked with 7200 mJ cm−2 UV energy (n=3). Significant differences from one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test are defined as *p < 0.05.

Tests were also performed in wet conditions (submerged in PBS) for polymer 3 and revealed that elastic modulus remains unchanged but failure stress and elongation at break were significantly lower for the wet samples (Supplemental Figure 3). The most important consideration for our application is the elastic modulus, since the elongation at break is well beyond the physiologically relevant values – physiologic strain regime of 15–20% in applications such as cardiac tissue engineering [12]. Furthermore, given that swelling of the samples takes place in solution and sample area is involved in the measurements, assessment in dry condition is preferred to ensure accuracy.

Polymer 4, with an elastic modulus of 51.4 ± 4.1 kPa, exhibited favourable mechanical properties for soft tissue application, swelling properties, and a high content of the molecule intended to impact adhesive properties. Based on this, this particular polymer composition was assessed further for adhesive properties. This selected polymer composition will be referred to as the adhesive patch (AP) polymer going forward.

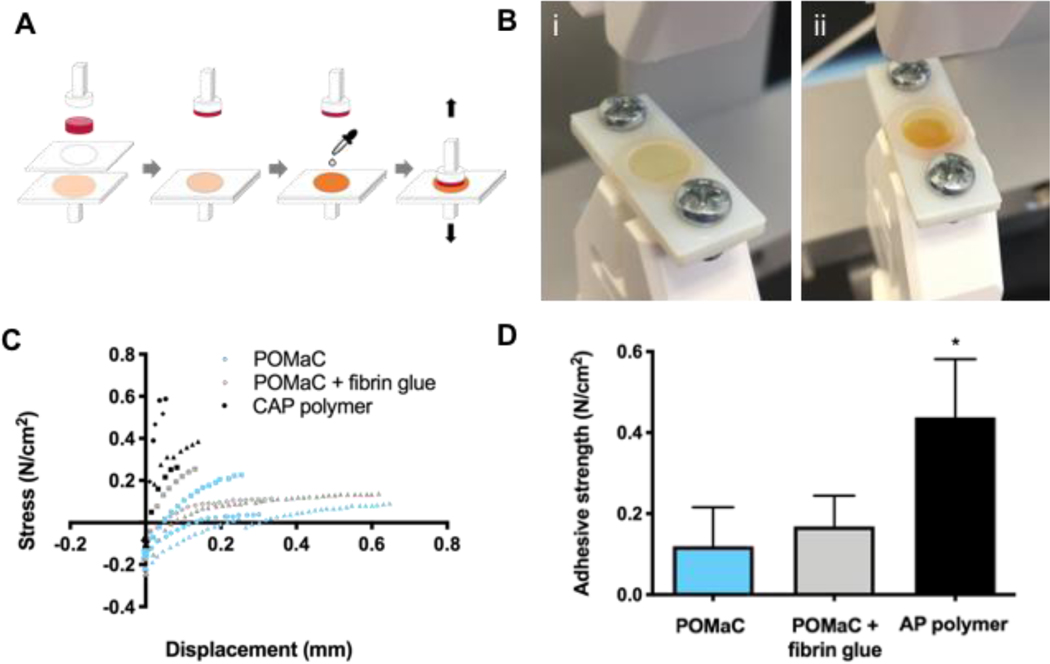

2.4. Adhesive properties

The adhesive properties of crosslinked AP polymer films with 40 wt% porogen prior to leaching was assessed. Porogen was added to impart a nanoporous structure according to previous work [11, 13]. Porogen concentrations within the range of previous work (i.e. 20 to 60 wt%) were attempted and a final porogen concentration of 40 wt% was selected based on ease of perfusion into the moulds while maintaining a high polymer content. The polymer samples were affixed to cardiac tissue and adhesive strength was assessed in a pull-off test wherein tissue samples placed onto polymer films were pulled apart at a constant rate (Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure 4). The AP polymer film was compared with a crosslinked film comprised of poly(octamethylene maleate (anhydride) citrate (POMaC), a commonly used citric acid polymer used as a material for many soft tissues such as blood vessels [13] and cardiac patches [11], which was applied to the heart here with the addition of fibrin glue. The adhesive strength of the AP polymer, oxidized with sodium periodate, was found to be 0.44±0.14 N cm−2 (Figure 4C,D). This is 3.7 times greater than the measured adhesive strength of POMaC films, and 2.6 times greater than that of fibrin glue on POMaC films. The fibrin glue administered on top of the POMaC film had an adhesive strength of 0.17±0.08 N cm−2.

Figure 4. Adhesive test of AP polymer.

A) Schematic of experimental set up for adhesive tests of AP polymer films. Minimal amount of sodium periodate is applied to polymer films prior to assembly onto rat heart tissue samples. B) i) AP polymer film in test grips. ii) Oxidized AP polymer film in test grips. C) Stress versus displacement curves for pull-off adhesive test. D) Adhesive strength of polymer films (n=3 for POMaC and POMaC + fibrin glue, n=4 for AP polymer). The effect of polymer films on adhesive strength was assessed using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. The asterisk denotes a significant (p<0.05) difference from other polymer groups.

Patches comprised of POMaC and AP polymer were fabricated according to previous work [11]. These patches were placed on the surface of rat hearts, and the AP polymer patch was sprayed with a solution of sodium periodate, then washed vigorously with PBS to evaluate adhesion to the tissue in the presence of external force in a wet environment. The POMaC patch moved from its original placement position while the AP polymer patch remained affixed to the tissue, demonstrating improved adhesive capabilities to the heart surface (Supplemental Figure 5 and Supplemental Movie 1 and 2).

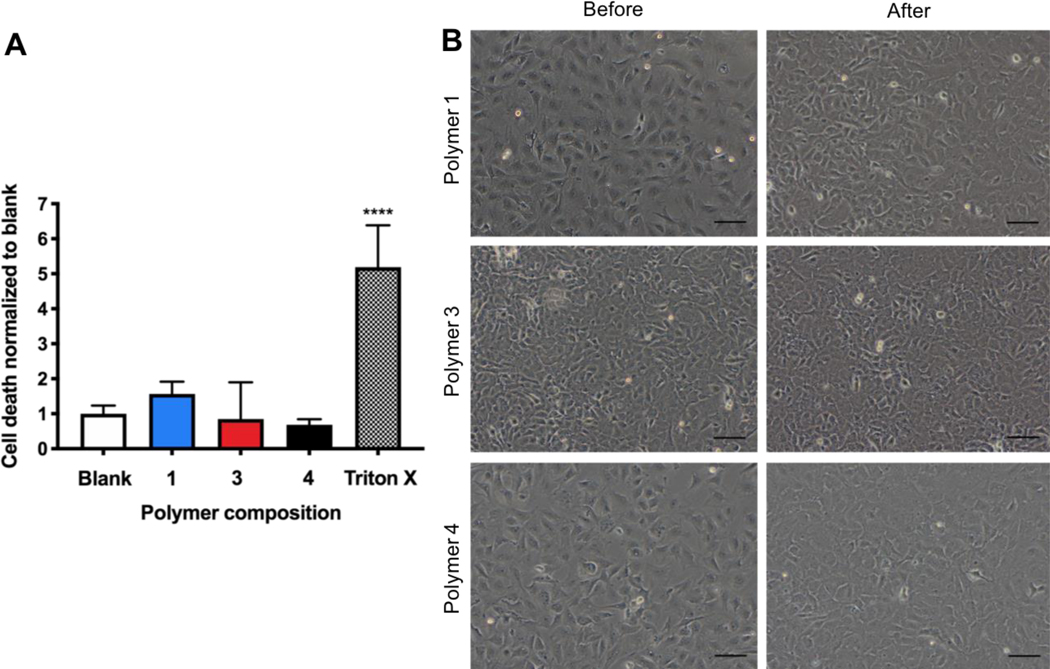

2.5. Cytotoxicity assessment

Evaluation of the leachable fraction of polymers using an LDH assay did not demonstrate cytotoxicity relative to the blank control (Figure 5A). Each composition evaluated behaved similarly in this respect, with insignificant measurements of cell death. Visible confirmation of cell viability after exposure to media containing polymer leachable fraction was evident (Figure 5B). Cardiac fibroblasts were used here, as an example of a cell abundant in this soft tissue. It was estimated that over 50% of cells in the heart are cardiac fibroblasts [14]. In addition, fibroblasts are present in many soft tissues the AP patch could be used for.

Figure 5. Cell viability using leachable fraction of crosslinked polymer in media.

A) Cytotoxicity evaluation relative to blank control and positive Triton X control using LDH assay (n=4). Significant differences from one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test defined as **** p < 0.0001. B) Representative images of rat cardiac fibroblasts before and 24 hours after culture with media containing polymer leachable fraction. (Scale bars: 100 μm).

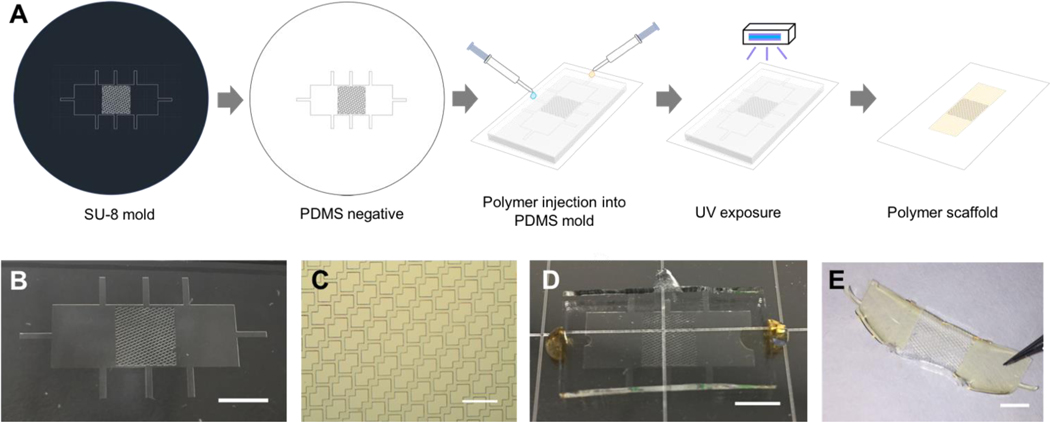

2.6. Fabrication of a scaffold with distinct adhesive and non-adhesive domains

A novel patch design was used to generate PDMS molds and then polymer patches (Figure 6A). The polymer patch included a centre section with an accordion-like honeycomb mesh design, which is favourable for the culture and formation of physiologically relevant cardiac tissue [12], and two outer sections for adhesion. Photolithography and soft lithography were used to generate the PDMS mold (Figure 6B) with 50 μm wide struts (Figure 6C). POMaC was perfused into the top centre section, and AP polymer with porogen was perfused into both sides of the PDMS mold (Figure 6D). After UV crosslinking, the resulting patch (Figure 6E), composed of both polymers, was removed from the mold and manually manipulated. The scaffold mesh section adequately resembled the PDMS mold, and the integration of the two polymers, which is required for formation of a uniform patch, was accomplished here (Supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 6. Two-component adhesive patch design.

A) Schematic representation of polymer patches fabricated using microfabrication technology. B) Adhesive patch PDMS mold. C) Mesh section of the adhesive patch PDMS mold. D) POMaC and AP polymer perfusion into the PDMS mold. E) Adhesive patch comprised of POMaC and AP polymer to form a middle mesh section and two adhesive flaps. (Scale bars: B = 5mm, C = 500um, D = 5mm, E = 3mm).

3. Discussion

In this work, polymers were synthesized for use as an elastic biomaterial with a spatially varying adhesive design. To achieve the objective of generating a suitable polymer composition for this application, several key criteria were upheld. Specifically, the polymer should include a molecule capable of imparting adhesive properties, it should exist as a liquid that can be molded into a patch and crosslinked, and once crosslinked, it should possess physiologically relevant elastomeric properties. Several synthesis conditions for the reaction of four monomers were used and one particular condition resulted in a material that satisfactorily met our requirements. This material was then assessed for its ability to adhere to a tissue.

A polymer composition, polymer 4 or AP polymer, was found to be a favourable composition for cardiac patch applications. Possible fragments containing various junctions between monomers that, together, comprise the polymer and contribute to its overall properties are indicated (Supplemental Figure 2). The AP polymer possessed relatively high content of the catechol molecule intended to impart adhesiveness. The presence of vinyl groups to impart photocrosslinkability, a necessary feature for formation into patch shapes using microfabrication techniques, was confirmed through chemical characterization. A low swelling ratio was also achieved, which is favourable for formation into a patch to be used in wet environments. We expect that the rapid initial mass loss occurs due to the uncrosslinked material leaching out initially. As shown in Figure 2D, the mass loss that occurs over 7 and 28 days is substantially lower. Specifically, for polymer composition 4, AP polymer, the mass loss following the first 24 hours does not significantly increase. Due to this and the sterilization step required before use with cells or in vivo work, a leaching step in solvents (PBS followed by 70% ethanol for sterilization) is undertaken, which should ensure that any uncrosslinked polymer is removed and that the remaining polymer is stable for use as a patch.

The elastic properties of this material were demonstrated to be in a relevant range for cardiac tissue applications where cyclic contraction takes place. Specifically, the AP polymer film demonstrated an elastic modulus very close to rat myocardium, an example of a soft tissue. Furthermore, it’s modulus is comparable to the injectable cardiac patch we described in recent work with an elastic modulus of 69.3 ± 17.4 kPa (x direction) and 14.7 ± 1.56 kPa (y direction)[11]. Thus, this polymer composition is favourable for the future cardiac patch application.

The oxidized polymer film fabricated in this work demonstrated higher adhesive strength in pull-off tests than the material currently used by our group for cardiac tissue patches, POMaC, and POMaC with the addition of fibrin glue. While the value of the adhesive strength reported is lower than some reported in literature, it is important to note that our patch demonstrates 2.6 times greater adhesive strength than the materials that are currently used to adhere patches to tissue surfaces (i.e. fibrin glue). A notable difference between other adhesive strength analyses reported in literature is the method of testing. While a lap-shear adhesive test is sometimes performed, the pull-off test of adhesive strength, which was used in this report, is another option, but may result in different adhesive strength outcomes. For example, Lang et al. demonstrated adhesive strengths in the range of ~0.5 to 2 N/cm2 for their surgical glue when tested in a similar pull-off adhesion testing, and this material was considered a successful glue option for surgical applications [3]. It is important to note that their analysis of commercially available fibrin glue (TissuSeal) demonstrated an adhesive strength in a similar range to our report, below 1 N/cm2. The relative improvement in adhesive strength from our controls is more important than the exact adhesive strength given the differences in experimental analysis. The fibrin adhesive concentrations used in our experiment were the same as that used in recent work to attach a cardiac patch [11] and is therefore used as a standard with which to compare our new adhesive polymer. Furthermore, the oxidized AP polymer patch performed better as an adhesive cardiac patch when compared to a POMaC control upon an in vivo application.

The enhanced adhesion of the oxidized AP polymer is expected due to the ability of catechol groups to bind with tissue in a number of ways. Adhesion of catechols can occur through metal complexation and hydrogen bonding. Furthermore, when oxidized to the quinone form, using an oxidizing agent such as sodium periodate, reactions can occur with functional groups present on biological surfaces (–NH2, –SH, –OH and –COOH) through Schiff base reactions and Michael addition reactions, or alternatively, quinones can form free radicals which are then able to crosslink to other groups in the polymer [4, 8, 15].

The improved adhesion we measured for our polymer film is promising. Many bioadhesive glues have been developed that utilize the mussel inspired DOPA/dopamine chemistry. Notably, a film composed of rose bengal-chitosan, blended with L-DOPA to impart adhesion when activated with a photosensitizer and green light, was developed as a tissue support patch in surgical applications [16]. While this work involved simple synthesis procedures in a favourable approach, the chitosan film is suitable for some, but not all applications. In particular, one area that we focus on is the use in cardiac tissue engineering, and this is the application for which our mechanical properties were tailored. The synthesis steps involved in generating our polymers allow for the tuning of the mechanical properties of the patch. While chitosan film has many favourable properties as a biomaterial patch such as biodegradability, flexibility, and porosity [17], synthetic polymers do offer some advantages for certain applications such as reduced batch-to-batch variability and increased control over physical properties and degradation rates [18]. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, no other scaffold materials that utilize the DOPA/dopamine chemistry for adhesion to tissue in a spatially prescribed way currently exists. The addition of a photocrosslinkable molecule allows us to fabricate the material into a patch form easily. It also opens up the option of using this material as a photocrosslinkable bioadhesive glue.

Evaluation of the leachable fraction of polymers did not demonstrate cytotoxicity relative to the blank control. Future tests should include cytotoxicity analysis and in vivo biocompatibility assessments of polymer films adhered in the presence of the oxidizing agent. For applications such as cardiac patch technology, the patch should remain intact long enough to provide structural support after a heart attack, and thus a material that does not fully degrade over the long term, like our AP polymer, is favourable. Long-term biocompatibility assessments should be performed on this work going forward to ensure this material is adequate and safe for this purpose.

Similar materials have been shown to demonstrate low cytotoxicity and have also been used in vivo with degradation and absorption without significant inflammatory response [8]. Based on work using similar synthesis methods and composition (i.e. PEG, dopamine, citric acid), we expect that the degradation products of our material will not demonstrate significant cytotoxicity and that cell proliferation and morphological assessment would demonstrate viability [8, 19]. Moreover, in vivo experiments with materials containing these similar components indicated improved wound healing [8, 19] and minimal inflammatory response [8, 20]. Our own previous published work using polymers containing the other similar components (i.e. maleic anhydride, citric acid) indicate biocompatibility [11, 21].

In terms of the oxidizing agent, sodium periodate, numerous papers report its use in similar approaches [8, 20, 22, 23]. In vivo experiments using a polymer with 8 wt% sodium (meta) periodate indicated that only minor acute inflammation resulted, and improved wound healing of the wounds treated with this approach [8]. It is reasonable to expect that in small concentrations, this oxidizing agent will not cause issues of cytotoxicity given that in the oxidation reaction of dopamine, electrons will be consumed by the periodate ion, forming the reduction product iodate ion (IO3−), which can be again reduced to the non-toxic iodide ion (I−) [22, 24].

The patch design established here is novel in two ways: 1) a patch that contains both flaps for adhesion and sections designed to mimic soft tissue elasticity and where in future, cells could be grown; and 2) a patch that integrates two distinct polymers through perfusion into microfabricated molds and integrated by photocrosslinking. The stability of the patch during manual manipulation indicates that both polymers were adequately crosslinked within and between themselves. This demonstrates that this is a realistic fabrication approach to continue using in future experiments.

A related cardiac patch design from previous reports possessed a scaffold and flap sections to aid in the culturing of tissues around the scaffold in a custom-designed bioreactor [11]. This design was used for different elastomeric polymers and viable, beating cardiac tissue around the scaffold mesh between polymer flaps was established in both cases [9, 11]. However, these patches lacked adhesive capability, leading to the development of the novel design reported here. Another cardiac patch comprised of a distinct centre region to impart a given function – in that case, conductivity – was developed by Mawad et al. [25]. This work demonstrated that a conductive centre could be incorporated into a chitosan film backing layer that was able to adhere to tissue upon the addition of a photoactivated dye and green laser. Here, we strived to generate a patch that also possess distinct regions, but with a focus on achieving desired mechanical properties and a centre mesh scaffold. An anticipated future direction is to use our dual-component adhesive patch to culture cardiac tissue around the scaffold mesh while maintaining the AP polymer flaps for use to secure the entire system to the tissue surface. It is important to note that selection of a polymer for the centre mesh section can be made to support culture of specific cell types, such as POMaC for culture of cardiac tissue. In vivo assessment will be required in future work to evaluate its efficacy and effect on cardiac function.

4. Conclusion

A novel polymer was synthesized to possess photocrosslinking capability, elastic properties matching cardiac tissue, and a molecule to impart adhesive capability. Based on assessments of polymer chemical and physical properties, a favourable adhesive patch polymer composition was selected and used in evaluations of adhesive strength. The AP polymer in oxidized form achieved greater adhesive strength to cardiac tissue than previously used cardiac patch polymers and fibrin glue, as an example of soft tissue application. Finally, the AP polymer was used in the fabrication of a dual-component patch containing adhesive polymer flaps and scaffold mesh sections, resembling the familiar Band-Aid. This novel design is tailored towards use as a cardiac tissue patch that can adhere to the outer surface of the epicardium, with the goal of replacing the need for additional glue and sutures. In future studies, this material and patch design can be incorporated into future iterations of cardiac patches, or biomaterial patches in general, aimed to support or regenerate damaged tissue.

5. Experimental Section

5.1. Materials

Polyethylene glycol (Mn 400 g mol−1), maleic anhydride, citric acid, dopamine hydrochloride, 1,8-octanediol (OD), 1,4-dioxane, chloroform-d, 2-hydroxy-4′-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone (Irgacure 2959), poly(ethylene glycol) dimethyl ether (PEGDM, Mn ~ 500), thrombin from bovine plasma, fibrinogen from bovine plasma, and sodium (meta)periodate were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dialysis membrane (Spectra/Por Dialysis Membrane MWCO 1000) was purchased from Thomas Scientific (Swedesboro, NJ). Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184) was purchased from Dow Chemical (Midland, MI). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin, N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethane sulfonic acid (HEPES), GlutaMax supplement, and Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). All materials were used as received unless otherwise described.

5.2. Pre-polymer synthesis

Polymers were first synthesized by reacting PEG (Mn 400 g mol−1), MA, CA, and dopamine hydrochloride. The molar ratios of monomers are detailed in Table 1. CA, PEG and MA were added to a 250 mL triple-neck flask and heated to 140˚C. At 5 minutes, dopamine was added, and the reaction was maintained under nitrogen for the entire duration. The reaction was continued for a set time, at which point the pre-polymer was dissolved in 50 mL DI water and dialyzed for 1 day. Snap-freezing and 3 days of lyophilization were performed to obtain the purified pre-polymer solution.

For comparison, POMaC, was similarly prepared [11, 13, 26, 27]. POMaC was synthesized through a polycondensation reaction of OD, MA and CA. An equimolar amount of carboxylic acid groups to hydroxyl groups was maintained and a molar ratio of citric acid to maleic anhydride was kept at 1:4. The reactants were added to a 250 mL triple-neck flask and the reaction vessel was heated at high temperature until the reactants were melted. The vessel was transferred to an oil bath where the sample was held at temperature of 140°C and under nitrogen purge for 3 hours. The pre-polymer was dissolved in 1,4-dioxane and purified by drop-precipitation into deionized water, followed by drying under air flow.

5.3. Chemical Characterization

Pre-polymer samples were characterized using ATR-FTIR (Perkin Elmer Spectrum One). 32 scans were taken from 4000 to 550 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1. Corrections for ATR, baseline and smoothing were performed. We sought to analyze the pre-polymer properties for the material and used a drop of the pre-polymer to cover the entire ATR-FTIR probe. While there is a penetration depth limitation, we do not expect any differences in the bulk properties compared to the surface properties of a well-mixed polymer gel. The dissolved polymer material was also characterized by UV-vis and 1H NMR to elucidate the chemical composition further.

UV-visible spectroscopy (Lambda 25 UV/Vis Spectrometer) was used to determine the presence of dopamine in the pre-polymers. All pre-polymers were dissolved at 0.125 mg mL−1 in water except for POMaC pre-polymers which were dissolved in 1,4-dioxane, and spectra measured across a wavelength of 200–700 nm.

1H NMR (Agilent DD2 600 MHz spectrometer) was performed to confirm polymer structure. Pre-polymer samples were dissolved at 10 mg mL−1 in deuterated chloroform and chemical shifts were tested against the resonance of protons in TMS. Integration of peaks associated with specific protons in the monomers based on predictive software (CS ChemDraw Ultra) was performed to assess compositional ratios of the monomers within the pre-polymers (PEG: 4.16–4.42 ppm, MA: 6.35–6.58 ppm, DA: 6.61–6.91 ppm). CA did not have distinct peaks and was therefore not assessed.

5.4. Film sample preparation

To generate crosslinked polymer films, 5wt% photoinitiator (PI), Irgacure 2959, was added to the pre-polymer to generate a pre-polymer-PI mixture. In specified cases, 40 wt% PEGDM was added to act as a porogen, resulting in a pre-polymer-PI-porogen mixture. The mixtures were stored at 4˚C under nitrogen in the dark. The pre-polymer mixtures were perfused into custom molds fabricated by generating PDMS negatives from 3D-printed molds and assembling the PDMS molds onto glass slides. Molds of the following three dimensions were used: 1) 6 mm diameter by 0.3 mm thick circular discs, 2) 10 mm diameter by 0.3 mm thick circular discs, and 3) 10 by 4 by 0.3 mm rectangle strips. Once perfused with pre-polymer mixtures, the filled molds were exposed to UV light. The PDMS molds were removed from the glass and the film sample was placed in PBS for 15 minutes to wash out porogen and PI and to facilitate removal of the sample from the glass slide.

5.5. Physical characterization

The pre-polymer-PI mixtures described in section 5.4 were perfused into 6 mm diameter, 0.3 mm thick PDMS molds assembled on glass slides. Samples were exposed to varying amounts of UV energy and the minimum energy required to generate a solid film that could be peeled off the glass and remain intact was assessed.

Swelling tests were performed on polymer strips, exposed to UV energy (2500 or 7200 mJ cm−2), and cut into rectangles of 2.5 × 4 × 0.3 mm. Samples were submerged in water for 24 hours. Swelling was determined by equation (1) where m is the mass of the sample after 24 hours in water and mi is the initial dry mass of the sample.

| (1) |

5.6. Degradation analysis

The pre-polymer-PI mixtures were perfused into 6 mm diameter, 0.3 mm thick PDMS molds assembled on glass slides. Samples were exposed to 5000 mJ cm−2 UV energy, weighed and placed in PBS at 37°C with. At a specified time, PBS was removed, and samples were lyophilized for 2 days to remove any residual liquid. Final mass after degradation was measured. Degradation was determined by equation (2) where m is the mass of the sample after degradation in PBS and mi is the initial mass of the sample.

| (2) |

5.7. Mechanical properties

Pre-polymer-PI mixtures were perfused into rectangular molds (10 × 4 × 0.3 mm) and crosslinked using with UV energy (2500 or 7200 mJ cm−2). Custom-designed 3D printed sample holders affixed to the Myograph (Kent Scientific) were used to hold samples at a starting distance of 1.000 mm apart. Samples were placed onto a layer of double-sided tape on the sample holder, and subsequently affixed with epoxy glue (Fast Setting Epoxy, Permatex). Care was taken to ensure that the epoxy was spread thinly and did not contact the section of the polymer to be stretched. The procedure outlined in previous work [11, 28] was carried out to evaluate the mechanical properties of the samples. Briefly, the sample holders affixed to the Myograph with polymer strip samples attached were separated at a strain rate of ~1 mm min−1 until material failure. Force transducer and displacement readings were recorded and converted into values of strain and engineering stress, from which Young’s Modulus was determined. For assessment in wet conditions, samples fixed onto the holders were submerged in PBS for 5 minutes prior to testing.

5.8. Adhesive tests

Five adult female Sprague-Dawley rats were humanely euthanized according to a protocol approved by the University of Toronto Animal Care Committee. Rat hearts were extracted, washed with PBS, and placed in a rat heart slicer with 1 mm coronal slice intervals. Slices were made on the four outer sides of the heart using a razor blade to create 2 mm thick tissue samples. A 6 mm diameter bore was subsequently used to cut tissue slices into small circular samples. Extracted tissue samples were kept in PBS at 4°C and prior to testing, tissue samples were maintained at room temperature on PBS soaked gauze for at least 15 minutes.

A modified method based on the ASTM standard test for the assessment of strength properties of tissue adhesives in tension (F2258-05(2015)) was employed. The grip size was reduced based on the distinct characteristics of our material [3] and custom-designed holders were 3D printed and used for securing the polymer and tissue samples. Tissue samples were glued onto the tissue holder using cyanoacrylate glue. Although cyanoacrylate glues have strong adhesion properties, they have toxic degradation products, are brittle and solidify in the presence of water, and result in inflammatory response and tissue necrosis [7, 29], eliminating them as a desirable option for in vivo applications.

The pre-polymer-PI-porogen mixture was perfused into 10 mm diameter PDMS molds described in section 2.4 and exposed to 7200 mJ cm−2 UV energy. The polymer film disc was soaked in PBS and placed on a bottom sample holder with the use of double-sided tape. A top sample holder was screwed on top to further secure the polymer sample. The polymer-containing holder was then placed into the equipment grips and the tissue sample was placed on top and fastened into the grips.

Three sample conditions were evaluated. For testing of the dopamine polymer, prior to placement of the tissue sample to the polymer sample, 5 μL of 4.8 wt% sodium (meta)periodate, a common oxidizing agent, in distilled water was pipetted onto the polymer and left for 1 minute before the tissue sample was attached (Figure 4A). Control samples of POMaC film (Supplemental Figure 4A) and POMaC film with fibrin glue (Supplemental Figure 4B) were also evaluated. Customized fibrin glue was generated by combining 110.5 mg mL−1 fibrinogen and 500 IU mL−1 thrombin with the gelation time of 5–10s. One drop of fibrinogen was applied through a 25-gauge needle onto the polymer followed by one drop of thrombin. After 30 seconds, tissue samples were placed on top of the gel.

Tissue samples in holders were placed securely onto polymer samples in holders for 10 minutes prior to separation. Samples whose placement shifted in the grips were discarded resulting in sample sizes of three or four for each condition. For each test, the samples were separated at a crosshead speed of 2 mm min−1. The maximum initial load sustained was recorded and divided by the bond area to find the adhesive strength.

Polymer material adhesion to heart tissue was also assessed in vivo. Scaffold molds were fabricated according to previous work [11]. POMaC and AP polymers were perfused into each mold to generate scaffolds composed of each polymer for application to the heart. All procedures were performed according to a protocol approved by the University of Toronto Animal Care Committee. Adult Lewis rats (~250 g, Charles River, USA) were selected and assigned randomly an AP polymer or POMaC scaffold. The animals were anesthetised by isofluorane inhalation (3% v/v) and after thoracotomy a scaffold was placed over the left ventricle with tweezers, followed by administration of a sodium periodate solution (8 wt% in ddH2O) to oxidize the scaffold material. This was followed by the vigorous administration of PBS (~ 1mL) to the heart surface in attempt to dislodge the scaffold.

5.9. Cytotoxicity

Fibroblasts were isolated from the hearts of one litter of ten neonatal rats according to previous reports [26] and seeded in a 12 well plate at a density of 100,000 cells per well. Pre-polymer-PI mixtures were perfused in 6 mm diameter molds described in section 2.4 and crosslinked with 8000 mJ cm−2 UV energy. Samples were removed from the molds and soaked in PBS for 3h, soaked in 70% ethanol overnight to sterilize, and then washed in PBS for at least 3 hours. Polymer samples were placed into 12-well plates with 5 mL phenol red-free DMEM containing glucose (4.5 g L−1), 10% (v/v) FBS, 1% (v/v) HEPES buffer, 1% (v/v) GlutaMAX-I and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Conditioned media, 1mL, was then used to culture cells. After 24 hours, cells were imaged, and media was removed for viability assessment using an LDH assay.

5.10. Patch design and fabrication

A patch was designed using AutoCAD software. Standard SU-8 photolithography techniques were used to fabricate the silicon wafer. Laser printer generator (Heidelberg uPG 501) was used to generate a chrome photomask with the desired pattern from a CAD design. SU-8 photoresist was spin-coated on a silicon wafer according to the manufacturer’s guidelines for a 45 μm-thick film and subsequently exposed to 365-nm UV using a mask aligner (OAI model 30), through the chrome photomask. Pre-exposure bakes and post-exposure bakes were performed according to manufacturer’s guidelines. The silicon wafer was submersed in SU-8 developer solution to dissolve the unexposed photoresist. A negative PDMS mold was created pouring PDMS elastomer and curing agent (1:10 ratio) over the wafer, degassing, and baking for 1hr at 80°C. POMaC with 5 wt% Irgacure 2959 and dopamine polymer with 40 wt % PEGDM and 5 wt% Irgacure 2959 were perfused into the mold in separate inlet channels and allowed to exit from outlet channels to generate a two-component patch. Molds containing the polymer mixtures were exposed to 7200 mJ cm−2 UV light. The PDMS was removed from the glass and the film sample was placed in PBS for 15 minutes. Images were obtained using optical microscopy (Olympus CKX41).

5.12. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. All data are shown as the average ± the standard deviation and differences with p < 0.05 were considered significant. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test method were used to assess statistical differences. Sample size for each measurement was in the range of n=2 to 5 and it is clearly indicated in the caption of each figure.

Supplementary Material

A POMaC patch was placed on the rat heart and subsequent rinsing with PBS resulted it its displacement.

An AP polymer patch was placed on the heart and oxidized by spraying sodium periodate solution onto the patch. The patch was rinsed with PBS and remained fixed in place.

6. Acknowledgements

We thank R. Civitarese for his assistance with tissue collection. This work was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation Grant-in-Aid (G-16-00012711), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (RGPIN 326982-10), NSERC-CIHR Collaborative Health Research Grant (CHRP 493737-16) and National Institutes of Health Grant 2R01 HL076485. MR was supported by NSERC Steacie Fellowship and Canada Research Chair.

Contributor Information

A. Dawn Bannerman, Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 3G9; Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Toronto General Research Institute, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Locke Davenport Huyer, Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 3G9; Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Toronto General Research Institute, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Miles Montgomery, Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 3G9; Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Toronto General Research Institute, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Nicholas Zhao, Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Claire Velikonja, Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 3G9.

Timothy P. Bender, Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 3G9

Milica Radisic, Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 3G9; Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Toronto General Research Institute, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

7 References

- [1].Li J, Mooney DJ, Nat. Rev. Mater 2016, 1, 16071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sharma B, Fermanian S, Gibson M, Unterman S, Herzka DA, Cascio B, Coburn J, Hui AY, Marcus N, Gold GE, Sci. Transl. Med 2013, 5, 167ra6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lang N, Pereira MJ, Lee Y, Friehs I, Vasilyev NV, Feins EN, Ablasser K, O’Cearbhaill ED, Xu C, Fabozzo A, Sci. Transl. Med 2014, 6, 218ra6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mehdizadeh M, Yang J, Macromol. Biosci 2013, 13, 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sanders L, Nagatomi J, Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng 2014, 42, 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tsui C, Klein R, Garabrant M, Surg. Endosc 2013, 27, 2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bouten PJM, Zonjee M, Bender J, Yauw STK, van Goor H, van Hest JCM, Hoogenboom R, Prog. Polym. Sci 2014, 39, 1375. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mehdizadeh M, Weng H, Gyawali D, Tang L, Yang J, Biomaterials 2012, 33, 7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Davenport Huyer L, Bannerman AD, Wang Y, Savoji H, Knee‐Walden EJ, Brissenden A, Yee B, Shoaib M, Bobicki E, Amsden BG, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2019, 8, 1900245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yen GC, Hsieh CL, Biosci. Biotech. Bioch 1997, 61, 1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Montgomery M, Ahadian S, Davenport Huyer L, Lo Rito M, Civitarese RA, Vanderlaan RD, Wu J, Reis LA, Momen A, Akbari S, Pahnke A, Li RK, Caldarone CA, Radisic M, Nat. Mater 2017, 16, 1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Engelmayr GC Jr., Cheng M, Bettinger CJ, Borenstein JT, Langer R, Freed LE, Nat. Mater 2008, 7, 1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang B, Montgomery M, Chamberlain MD, Ogawa S, Korolj A, Pahnke A, Wells LA, Masse S, Kim J, Reis L, Momen A, Nunes SS, Wheeler AR, Nanthakumar K, Keller G, Sefton MV, Radisic M, Nat. Mater 2016, 15, 669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Baudino TA, Carver W, Giles W, Borg TK, Am. J. of Physiol. - Heart C 2006, 291, H1015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Camelliti P, Borg TK, Kohl P, Cardiovasc. Res 2005, 65, 40; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ieda M, Fu J-D, Delgado-Olguin P, Vedantham V, Hayashi Y, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D, Cell 2010, 142, 375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Chan Choi Young, Suk Choi Ji, Jae Jung Yeon, Cho YW, J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 201; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kord Forooshani P, Lee BP, J. Polym. Sci. Pol. Chem 2017, 55, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ruprai H, Shanu A, Mawad D, Hook JM, Kilian K, George L, Wuhrer R, Houang J, Myers S, Lauto A. Acta Biomater. 2020, 101, 314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Di Martino A, Sittinger M, Risbud MV Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Reis LA, Chiu LL, Feric N, Fu L, Radisic M. J. Tissue Eng. Regener. Med 2016, 10, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang R, Li J, Chen W, Xu T, Yun S, Xu Z, Xu Z, Sato T, Chi B, Xu H. Adv. Funct. Mater 2017, 27, 1604894. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Liu Y, Meng H, Konst S, Sarmiento R, Rajachar R, Lee BP ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 16982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Davenport Huyer L, Zhang B, Korolj A, Montgomery M, Drecun S, Conant G, Zhao Y, Reis L, ACS Biomater M. Sci. Eng 2016, 2, 780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang H, Bré LP, Zhao T, Zheng Y, Newland B, Wang W. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brubaker CE, Kissler H, Wang LJ, Kaufman DB, Messersmith PB Biomaterials 2010, 31, 420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Burke SA, Ritter-Jones M, Lee BP, Messersmith PB Biomed. Mater 2007, 2, 203e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mawad D, Mansfield C, Lauto A, Perbellini F, Nelson GW, Tonkin J, Bello SO, Carrad DJ, Micolich AP, Mahat MM, J. Furman. Sci. Adv 2016, 2, e1601007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang B, Montgomery M, Davenport-Huyer L, Korolj A, Radisic M, Sci. Adv 2015, 1, e1500423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tran RT, Thevenot P, Gyawali D, Chiao JC, Tang L, Yang J, Soft Matter 2010, 6, 2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Montgomery M, Davenport Huyer L, Bannerman D, Mohammadi MH, Conant G, Radisic M, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2018, 4, 3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].a) Mizrahi B, Stefanescu CF, Yang C, Lawlor MW, Ko D, Langer R, Kohane DS, Acta biomater. 2011, 7, 3150; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Vinters H, Galil K, Lundie M, Kaufmann J, Neuroradiology 1985, 27, 279; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lin X, Liu Y, Bai A, Cai H, Bai Y, Jiang W, Yang H, Wang X, Yang L, Sun N, Gao H, Nat. Biomed. Eng 2019, 3, 632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A POMaC patch was placed on the rat heart and subsequent rinsing with PBS resulted it its displacement.

An AP polymer patch was placed on the heart and oxidized by spraying sodium periodate solution onto the patch. The patch was rinsed with PBS and remained fixed in place.