Abstract

This Perspectives of the published essential medicinal chemistry of cannabidiol (CBD) provides evidence that the popularization of CBD-fortified or CBD-labelled health products, and associated health claims, lack a rigorous scientific foundation. CBD’s reputation as a cure-all puts it in the same class as other “natural” panaceas, where valid ethnobotanicals are reduced to single, purportedly active ingredients. Such reductionist approaches oversimplify useful, chemically complex mixtures in an attempt to rationalize the commercial utility of natural compounds and exploit the “natural” label. Literature evidence associates CBD with certain semi-ubiquitous, broadly-screened, primarily plant-based substances of undocumented purity that interfere with bioassays and have a low likelihood of becoming therapeutic agents. Widespread health challenges and pandemic crises such as SARS-CoV-2 create circumstances under which scientists must be particularly vigilant about healing claims that lack solid foundational data. Herein, we offer a critical review of the published medicinal chemistry properties of CBD, as well as precise definitions of CBD-containing substances and products, distilled to reveal the essential factors that impact its development as a therapeutic agent.

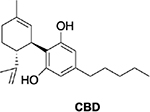

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

CBD is big business. The industry surrounding the use of cannabidiol (CBD) in products from cosmetics and clothing, to food, beverages, and both over-the-counter supplements and prescription pharmaceuticals is staggering. With a global market estimated at $4.6 billion in 20181 and projected CBD sales surpassing $20 billion in the US alone by 2024,2 the rate at which the public is consuming or coming into contact with this chemical has increased steadily. Similar to the expansive literature surrounding another widely used natural product we recently reviewed (curcumin and curcumin-containing products),3 getting a handle on the published knowledge surrounding CBD and CBD-containing products is daunting. The sheer volume and breadth of information on CBD is a challenge for consumers and researchers alike as they seek to understand the true utility and value of both pure CBD and many CBD-labelled products. Hasty conclusions on the human-health impact of CBD, stemming from experiments that are often only remotely connected to biological relevance, add to the confusion. The health emergency presented by SARS-CoV-2 (and purported “cures” thereof), which emerged during the writing of this article, is a stark reminder to the scientific community that we have a serious responsibility to bring clear evidence about product composition and quality as well as the safety and efficacy to any claim for the improvement of human health.

What’s in the Name?

As with many natural products, much conflation and confusion exist between plants (here: cannabis and/or hemp), products derived from them, and a single chemical entity (here: CBD). This semantic reductionism distills one or a few species of plant (here: Cannabis sativa, C. indica, or C. ruderalis) down to two compounds: Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and CBD, creating a damaging assumption that single and/or major ingredients can explain the ethnobotanical use of an entire plant. Such reductionism ignores both the whole-plant aspect of ethno-based biological activity as well as the metabolomic chemistry of the plant, both of which are key tenets of contemporary pharmacognosy. Recent and cutting-edge work highlights the importance of considering polypharmacology and/or synergistic mechanisms of dietary and medicinal plant bioactivity.4–6 Even when only considering cannabinoids (vide infra), the chemodiversity of the CBD-producing plants is expansive, leaving no justification for semantic (or scientific) reductionism.

The widespread promotion of CBD as a quasi-synonym for any Cannabis or hemp product has an interesting analogy in the global dietary supplement market, where the term “curcumin” is widely, and mostly erroneously, used to refer to crude preparations from the rhizome of Curcuma longa.7 Confusion on this level has great potential to interfere with, or even void, the scientific validity of discussions surrounding CBD, as well as other erroneously-promoted natural product isolates. Despite this concern, there are stark differences between the case of Cannabis/THC/CBD and that of Curcuma/curcumin. For example, little evidence exists that the curcumin molecule itself has an in vivo effect after it has been consumed by humans. In comparison, THC has a known, pronounced CNS effect, which is part of the rationale behind its special status and regulation in many countries. CBD, while structurally very similar to THC, does not seem to share its psychoactive properties.8

Aims of this Perspectives

The goal of this work is to summarize the scientific facts known about CBD and provide a useful reference for anyone wishing to understand the hype surrounding CBD. This Perspectives covers: the legal status of CBD in the U.S.; fundamentals of CBD as a natural product and its potential status as an IMP (invalid metabolic panacea); natural sourcing of CBD and the challenges of quality control (the synthetic sourcing of CBD is covered in a companion Perspectives); the fundamental chemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) of CBD; and an indication-guided analysis of human clinical trials. Our work is current up to March 1, 2020, and generally relies on information published within the last five years. We have steered away from in vivo animal studies because they are too numerous, difficult to interpret, and subject to experimental artifacts,9 choosing instead to focus on the evidence for therapeutic utility presented by well-designed human clinical trials.

While the verdict on CBD remains to be decided, our perspective is that it is certainly not the universal panacea that it is touted to be. Nor is it an innocuous natural substance that should be unregulated in the marketplace and/or used to fortify products for credulous human consumption. This Perspectives hopes to clear up some of the smoke clouding the discussion of CBD by providing essential facts that help cut through the media chaos.

Ten Facts about CBD

CBD is a promoter of DDI (drug-drug interactions) and potentiates the action of many drugs (5–10 μM)10

CBD is a membrane interactor: it promiscuously affects ion channels by membrane pressure and direct binding (0.1–5 μM)11,12

CBD has a strong “meaning effect”: individuals expect it to work13

CBD is 6% orally bioavailable by some reports14

CBD’s typical dose in non-medicinal products is much lower than that used in clinical trials and in prescriptions (25 mg in a typical non-medicinal product versus 150–1500 mg/day clinical trials)15

“CBD has the potential to harm you” (similar to other drugs)16

CBD can be converted to THC by chemical means, but appears not to convert to THC under physiological conditions (vide infra)

CBD is currently considered an illegal supplement (“It is currently illegal to market CBD by adding it to a food or labeling it as a dietary supplement”)16

“CBD” is a popular product label, but often misleading: frequently “CBD” products contain many other, chemically complex ingredients in addition to varying, sometimes small amounts of CBD. Valid CBD label-claims require rigorous analytical characterization of its identity, purity and stability (elements of Residually Complexity; vide infra), rather than blanket statements such as “pure” or “natural”.

CBD has not displayed meaningful activity on its own in a double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Trials that underlie claims of a wide range of health have predominantly used CBD as minor ingredient or part of adjunctive therapy schemes that co-administer other substances/preparations, often seeking to leverage “botanical synergy” (also involving Residual Complexity; vide infra). This is also important considering that CBD displays strong DDIs (vide infra).

Natural Product (Bio-)Chemistry Overview

CBD is Just One Molecule in the Vast Chemical Space of Cannabinoids

Formally, CBD can be considered to have a tetrahydro-biphenyl skeleton: a bicyclic core that represents an adduct formed by the monoterpene, p-cymene, and the alkylresorcinol derivative olivetol (Figure 1). CBD can be converted into the tricyclic dibenzopyrane, Δ9-THC (THC), via an acid-catalyzed reaction.17,18 While CBD and THC are prominent members of the cannabinoid family of compounds, they are just a part of the numerous representatives of the chemical subspace of the terpenyl-alkylresorcinol metabolome of plants of the Cannabis genus. Irrespective of their close biogenetic relationships (vide infra, Biosynthetic Pathways), the cannabinoids represent a structurally diverse chemical space. While this diversity has been explored relatively extensively due to the strong general interest in Cannabis phytochemistry, it offers much untapped structural potential - for reasons that become evident from the following chemical and biogenic rationales.

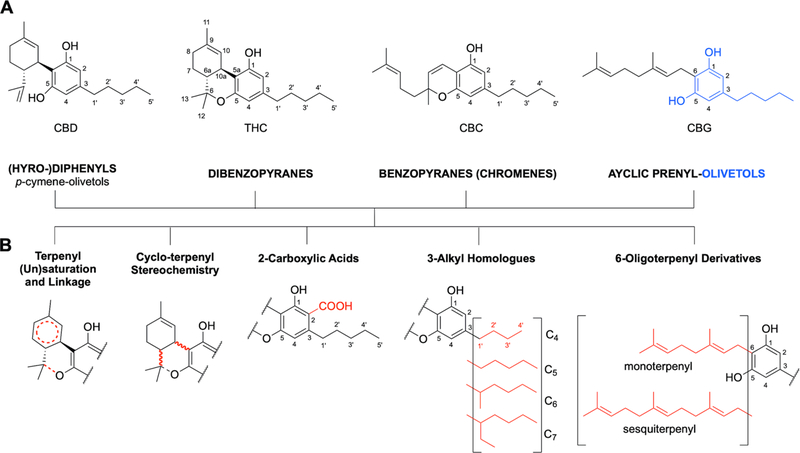

Figure 1.

(A) The tetrahydro-diphenyl skeleton of CBD in the context of the base structures of three other main classes of cannabinoids (dibenzopyranes, benzopyranes, and acyclic prenyl-olivetols); as well as (B) five principal structural variations that occur in all cannabinoid classes. Different combinations of these four classes, with variations such as these presented as well as additional redox-driven metabolic modifications, explain why CBD and THC are just two molecules within the complex metabolome of cannabinoids.

The expression of naturally occurring cannabinoids (phytocannabinoids) undergoes dynamic changes during the course of plant growth19 and consist of four major classes of molecules with distinct skeletons (Figure 1). All of these major classes contain an olivetol core (i.e., a resorcinol) in which one hydroxyl group is replaced by an alkyl chain (C5 in olivetol; with linear and branched C4 to C7 alkyl chains also known to occur). In addition to the bicyclic tetrahydro-diphenyl and tricyclic dibenzopyrane classes, benzopyranes (syn. chromenes; prototype: cannabichromene [CBC]) and acyclic prenyl-olivetols (prototype: cannabigerol [CBG])20 are the other key classes of cannabinoids. Within each, there are a variety of possible metabolomic processes in the plant that effect further structural modifications, expanding the Cannabis metabolome in five major dimensions: (1) the variation of terpenyl saturation and linkage; (2) the terpenyl stereochemistry; (3) the presence vs. absence of C-2 carboxylation (“acids”); (4) the variation of length and branching of the olivetol alkyl chain (e.g., homologous cannabinoids);20 and (5) presence and variation of the monoterpene vs. sesquiterpene moieties. Collectively, this gives rise to a plethora of natural cannabinoid metabolites. The full breadth of the resulting cannabinoid chemodiversity likely remains to be explored. Moreover, cannabinoids are only one family among several phytoconstituent classes in Cannabis plants.

Biosynthetic Pathways

In the living plant and fresh plant material, many cannabinoids are present in the form of carboxylic acids. The underlying biogenic pathways are sufficiently well-characterized to allow for heterologous expression of the overall pathway.21 In plant material, CBD acid and analogous cannabinoids are readily decarboxylated to their neutral forms in the presence of heat and during other mechanical manipulation and/or storage. For example, dried and aged plant material contains both neutral and acidic forms of CBD. The extent of decarboxylation also depends on the extraction method and processing that occurs before the CBD content is measured.

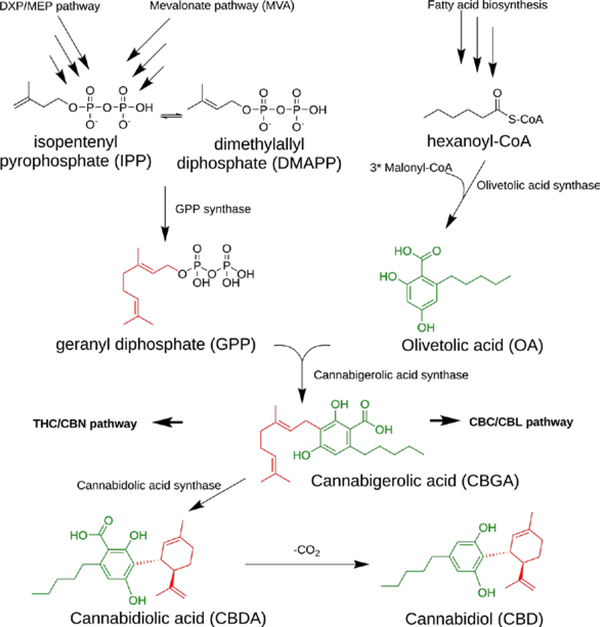

Cannabis sp. are prolific producers of terpenes and terpenoids, a phenomenon that can also be observed in other plants such as Eucalyptus sp. that are known to produce hundreds of these compounds.21,22 It is likely that most of the cannabinoids are produced at the intersection of three major biosynthetic pathways: the DXP (deoxy-xylulose phosphate; also called methyl-erythrol phosphate [MEP]) pathway, the MVA (mevalonic acid) pathway, and the fatty acid pathway that feeds a polyketide synthase (PKS), olivetolic acid synthase (Figure 2).21,23 The diversity of cannabinoids produced by Cannabis sp. is mainly achieved through non-enzymatic modifications occurring after the production of a common precursor.21,23 While predictive studies of the kinds of cannabinoids that could potentially be produced by these plants are unavailable, the diversity of metabolites arising from these pathways is congruent with the already hundreds of identified cannabinoids.

Figure 2.

The biosynthetic pathway of cannabinoids is the result of the intersection of three metabolic pathways in Cannabis sp.

CBD Residual Complexity, Purity, Identity, and Quality Control

When choosing a method of chemical separation of the cannabinoid metabolome, the occurrence of homologous alkyl and prenyl sidechains, single- vs. double cyclized monoterpene rings, and presence vs. absence of pyran/chromene rings (Figure 1) present a chromatographic challenge. These three structural permutations alone produce a mixture of molecules with closely similar polarities and overall molecular shapes. These challenges for the resolution capabilities of current chromatographic systems apply equally to analytical methods that depend on prior separation such as GC- and LC-MS, as well as to preparative methods including adsorbent-based column and countercurrent/centrifugal partition (CCC/CPC) chromatography that are employed for the targeted purification of cannabinoids, such as CBD. Accordingly, when working with Cannabis and related materials, it would be naive to assume that chromatographic peaks arise from pure compounds. Even narrow elution time windows probably contain residual amounts of congeneric cannabinoids and, therefore, represent cases of Residual Complexity (go.uic.edu/residualcomplexity).

Accordingly, CBD, THC, and any other “purified” individual cannabinoids are subject to the principles of Residual Complexity and its analytical implications. This caveat applies even when high purity has been demonstrated by a rigorous method, such as a combination of LC-UV/MS and quantitative NMR (qNMR),24 as the stability of high purity material and/or chemical changes during biological/clinical testing (i.e., Dynamic Residual Complexity) needs to be demonstrated separately. While thermoanalytical (DSC, TGA) purity assays for CBD are unavailable in the literature, they have recently been introduced for cocrystal forms of CBD.25 Extraction methods or synthetic methodologies used in the preparation of CBD products have a significant impact on what constitutes the final preparation labeled with/as “CBD”.

In addition, Residual Complexity can involve phytochemicals or synthetic reagents present in the original preparation that can be carried through to the final step, as well as known (e.g. decarboxylation) or unanticipated chemical transformations that may occur under the conditions used for extraction or purification. Some concern exists that CBD may rearrange to THC, but this transformation, while chemically feasible (vide infra), is not likely to occur during extraction, separation, or purification.26 The unique fingerprints of such residually complex materials can be used to help identify the source and method of production of a CBD product. Chemical fingerprinting methodology, currently used to identify illegal/counterfeit drugs, could be adopted for cannabinoids to aid with the identification of the source (material, origin) of various CBD products.27

Considering the permutational variations and resulting close structural resemblance of natural cannabinoids, authentic CBD, including CBD reference materials, must undergo rigorous characterization involving at least HRMS supporting its molecular formula (C21H30O2), 1D/2D 1H and 13C NMR assignments, as well as physicochemical determination of its properties including UV, IR, melting (66–67 °C, although this is dependent on polymorph) and boiling (189 °C) points, and optical rotation (−125°) (from scifinder.cas.org28). Ideally, the reference material is crystalline, and its quality is supported by X-ray diffraction analysis. Its universal detection, as well as simultaneous qualitative and quantitative capabilities,24,29 makes NMR a highly versatile analytical method that is particularly suitable for CBD and cannabinoids in general. This potential was already recognized in 2004 by Hazekamp, Choi, and Verpoorte,30 who utilized the relatively simple resonances of the uncoupled or meta-coupled aromatic hydrogens as well as that of the olefinic hydrogen in the monoterpene moiety to determine the purity of isolated cannabinoids, as well as their quantity, in extracts. A recently published quantitative NMR (qNMR) method permits the absolute quantitation of CBD using combined external (crystalline CBD) and internal (residual CHCl3 signal) calibration.31

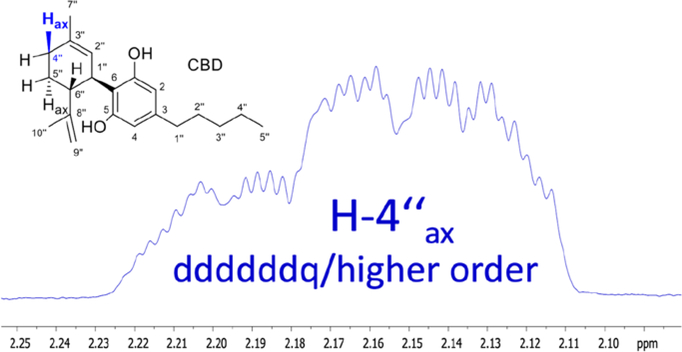

One important feature of the 1D 1H NMR spectra of CBD that has been underutilized to date pertains to the information richness of the underlying 1H,1H spin coupling systems. Considering the cyclic, unsaturated partial structure of CBD, it is anticipated that not only geminal and vicinal (2/3J), but also a wealth of long-range couplings (predominantly 4/5J) are present in the molecule. This gives rise to numerous fine splittings in the apparently simple “singlet” signals that reveal themselves as “multiplet” resonances upon closer inspection. Another complication of interpreting the 1D 1H NMR spectrum of CBD, which actually represents a highly characteristic feature for the identification of the compound, relates to the higher order coupling effects of closely resonating methylene and methine hydrogens. Recent advancement in the quantum mechanics-based computational analysis of 1H NMR spectra has enabled a full interpretation of such spectra, using an approach termed HiFSA (1H iterative Full Spin Analysis),32 leading to the extraction of full sets of chemical shifts (δ) and coupling constants (J).

One major advantage of HiFSA profiles is that they enable the calculation and comparison of 1H NMR spectra at any field strength,32 thus covering all practically available NMR instruments from 40 to 900+ MHz. Another feature of HiFSA is that it can utilize digitally archived raw NMR data, as long as they are maintained and shared among scientists and practitioners using FAIR principles.33,34 This enables the comparison of samples and verification of compound identity over a long period of time, across multiple laboratories, and without the need for authentic reference materials. In order to help leverage the capabilities of HiFSA profiles for future applications and demonstrate the power of raw data sharing, we have performed a retrospective HiFSA analysis of a 2004 CBD raw 1H NMR data (FID; Supporting Information S1). Figure 3 shows how the highly characteristic single 1H NMR resonance of H-4”ax (axial) can serve as a fingerprint signal that represents the entire CBD molecule. This enables the use of routine 1H NMR spectroscopy for unambiguous identity assays via comparison of 1H NMR spectra at any field strength.32 Moreover, due to the inherently quantitative nature of NMR, appropriately acquired qualitative data can be utilized for qNMR-based CBD purity analysis that is independent on identical reference standards.

Figure 3.

The axial hydrogen, H-4”ax, is involved not only in multiple J-coupling within the monoterpene moiety, but its 1H NMR resonance is also affected by the close resonance behavior of its coupling partners. The resulting pronounced higher order effects of the ddddddq-type multiplet encode the spin parameters of half of the molecule in such a way that the H-4”ax resonance alone becomes diagnostic for the entire CBD molecule. See S1, Supporting Information, for the detailed results of the underlying 1H iterative Full Spin Analysis (HiFSA).

General identity and purity assays for CBD involve liquid- and gas-chromatographic comparison with authentic reference material. However, product purity can deviate substantially from assumed grades or values, even when quantitatively measured against authentic standards, as the method is only as reliable as the characterization of the reference material. The vastly different abundance of the metabolites in crude cannabinoid mixtures explains why minor components can go undetected unless multiple preparative steps and/or orthogonal separation systems are employed. At the same time, minor components can be the principal or even sole factors for biological outcomes, as shown recently for a 0.24% impurity of an antimycobacterial agent.35 Likewise, a major “pure” component can exhibit only minor or no real effects. As the biological potency of individual compounds spans many orders of magnitude, correlations between compound abundance and observed potency can be counterintuitive when considered from a chemical perspective alone.36 Applied to CBD and the other cannabinoids, the concept of Residual Complexity has to be considered carefully when using materials for preclinical biological studies and/or for clinical interventions, including as nutritional supplements, and is essential for the reproducibility of any studies with such materials. The recent work by Citti et al. on the production and purity of CBD as well as the identification of the 3-butyl homologue as a common impurity confirms the relevance of the Residual Complexity for CBD and other cannabinoids.37 In their article, the authors also highlight the applicability of ICH guidelines (Q3A(R2)), calling for the impurity analysis of APIs to the level of 0.10% and 0.05% for daily doses of below and above 2 g of the API, respectively.37

Regulatory Overview

As of March 2020, the US Federal Drug Administration (FDA) had not approved the marketing of cannabis for the treatment of any disease or condition. The FDA has, however, approved one cannabis-derived product for medicinal use (Table 1), Epidiolex®️, which contains CBD as API and is only available from a licensed healthcare provider with a prescription.14,40 The FDA has not approved any other CBD products currently on the market in the United States. Epidiolex® is an oral solution that contains 100 mg/mL CBD, and the underlying patent refers to CBD from both Cannabis plant extracts and synthesis as potential sources. Inactive ingredients in this formulation include dehydrated alcohol [not less than 98% volume EtOH], sesame seed oil, strawberry flavor, and sucralose.41 Epidiolex® was approved for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut or Dravet syndrome in patients 2 years of age or older.39 Both syndromes are rare forms of treatment refractory epilepsy that represent <5% of all childhood epilepsies. Regarding the various products that contain (or claim to contain42) CBD and are marketed without a prescription, the FDA has published the following guidance, which we quote here for clarity.

Table 1.

Key terms and definitions38

| Material | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cannabis | Plant of the Cannabaceae family that produces biologically active cannabinoids, some of which are controlled under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) since 197039 |

| Marijuana | Cannabis plant that produces THC at 20%+ levels |

| Hemp | The plant Cannabis sativa L., and any part of the plant and all derivatives thereof with a THC content of < 0.3% (dry weight)39. Hemp can contain > 20% CBD |

| Hemp seeds/oil | Whole seeds or oil, containing fatty acid esters, that is expressed or extracted from seeds. These products contain 0% THC and trace levels of CBD |

| Cannabinoids | Family of chemicals that act on the endocannabinoid system. The cannabis plant synthesizes many cannabinoids, such as THC and CBD |

| THC | Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, a cannabinoid used for medicinal purposes and non-medicinally for its intoxicating effects. CAS# 1972-08-3 |

| CBD | Cannabidiol; a cannabinoid with an undefined mechanism; biosynthetically related to THC. Not intoxicating even at high doses. CAS# 13956-29-1 |

| Cannabis-derived products for medicinal use | Medicinal products containing cannabis or cannabinoids derived from the Cannabis plant (e.g., THC and/or CBD in well-defined proportions) |

| Synthetic cannabinoids for medicinal use | Medicinal products containing synthetically produced cannabinoids which typically mimic the effects of THC |

| Non-medicinal CBD products | Products containing CBD that are widely sold as herbal remedies but are not regulated as medicinal products |

| Non-medicinal cannabis | Material from the Cannabis plant that is not regulated as a medicinal product, widely used for its intoxicating effects |

| Non-medicinal synthetic cannabinoids | Synthetic cannabinoids that are typically not structurally related to naturally occurring cannabinoids and are not currently recognized for medicinal use (e.g. synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists, found in products such as “Spice”) |

“Under the FD&C Act [note: Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 1938], any product intended to have a therapeutic or medical use, and any product (other than a food) that is intended to affect the structure or function of the body of humans or animals, is a drug. Drugs must generally either receive premarket approval by the FDA through the New Drug Application (NDA) process or conform to a “monograph” for a particular drug category, as established by FDA’s Over-the-Counter (OTC) Drug Review. CBD was not an ingredient considered under the OTC drug review. An unapproved new drug cannot be distributed or sold in interstate commerce. FDA continues to be concerned at the proliferation of products asserting to contain CBD that are marketed for therapeutic or medical uses although they have not been approved by FDA. Often such products are sold online and are therefore available throughout the country. Selling unapproved products with unsubstantiated therapeutic claims is not only a violation of the law, but also can put patients at risk, as these products have not been proven to be safe or effective. This deceptive marketing of unproven treatments also raises significant public health concerns, because patients and other consumers may be influenced not to use approved therapies to treat serious and even fatal diseases. Unlike drugs approved by FDA, products that have not been subject to FDA review as part of the drug approval process have not been evaluated as to whether they work, what the proper dosage may be if they do work, how they could interact with other drugs, or whether they have dangerous side effects or other safety concerns.”39

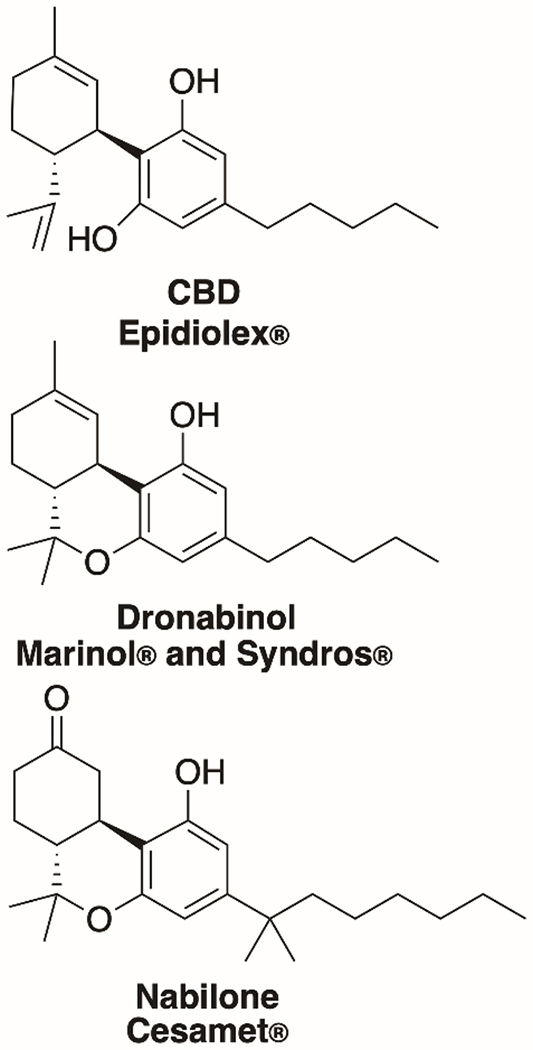

In addition to one CBD product, the FDA has approved three non-CBD cannabis-related drug products (Figure 4). Marinol® and Syndros® have both been approved for therapeutic uses in the United States, including for the treatment of anorexia associated with weight loss in AIDS patients. Both therapies include dronabinol as the active ingredient, a synthetic form of THC, which is considered the psychoactive component of cannabis. Cesamet® is an FDA-approved product that contains nabilone as the active ingredient, which is synthetically derived and has a chemical structure similar to THC.

Figure 4.

Structures of the active ingredients of FDA-approved drugs containing CBD or related compounds.

With these four exceptions, no product containing cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds (either plant-based or synthetic) has been approved as safe and effective for use in any patient population, whether pediatric or adult. Going even farther, CBD containing products are explicitly excluded from being sold as “dietary supplements”. Following section 201(ff)(3)(B) of the FD&C Act [21 U.S.C. § 321(ff)(3)(B)], if a substance (here: CBD) is approved as an active ingredient in a drug product, then products containing that substance are excluded from the definition of a dietary supplement.

Conversion of CBD to THC

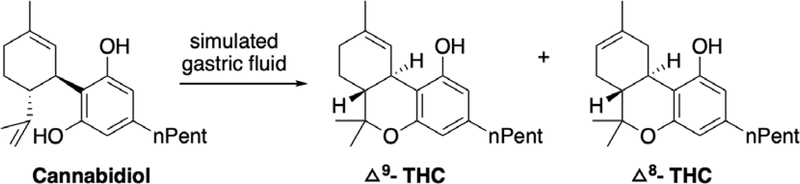

(–)-CBD was the major phytocannabinoid in extracts of Cannabis sativa L. plants from which it was first isolated and structurally characterized in 1940.43,44 Jones subsequently confirmed the chemical structure by x-ray crystallography in 1977.45 CBD is chemically unstable at room temperature, undergoes air oxidation to form cannabidiol hydroxyquinone,46,47 and can isomerize to other cannabinoids in acidic environments. Gaoni and Mechoulam reported the isomerization of CBD to THC and other cannabinoids under aqueous acidic conditions, however this conversion results in a mixture of isomeric THCs in low yields. More recently, in a patented method, CBD was converted to Δ9-THC in quantitative yield using boron trifluoride etherate as a Lewis acid in anhydrous CH2Cl2.48 The sensitivity of CBD to acidic conditions has led to the hypothesis that conversion of CBD to THC under the gastric acidic environment in vivo can cause adverse pharmacological effects from CBD-based marketed products.49 This conversion has been debated in the literature however, and there is no direct evidence of the conversion of CBD to THC in the human gut.50 Two in vitro studies have used simulated gastric fluid to test the plausibility of this conversion. The first study reported the formation of THC in 2.9% yield along with other cannabinoid products in artificial gastric fluid without pepsin.51 In 2016, Zynerba Pharmaceuticals reported the formation of psychoactive cannabinoids (Δ9-THC and Δ8-THC) by exposing CBD to simulated gastric fluid (SGF),49 showing 98% conversion of CBD to these THC products (~49% yield) within 2 h by UPLC-MS analysis (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Acid instability of cannabidiol as reported by Zynerba Pharmaceuticals.47

However, Grotenhermen52 and Nahler50 later refuted the in vivo relevance of this report by pointing out that the SGF protocol differs significantly from the physiological conditions present in the stomach. Furthermore, these follow-up studies reviewed data from previously conducted clinical trials of CBD and found no reports of THC or related metabolites. A recent study by the Lachenmeier group further ruled out the feasibility of CBD to THC transformation.53 They conducted stability studies of pure CBD solutions stored in SGF or subjected to a range of storage conditions, such as heat and light. Mass spectrometric (LC/MS/MS) and ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatographic/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometric (UHPLC-QTOF) analyses could not confirm the formation of THC under any of these conditions.

None of the in vitro experiments reviewed herein represent a sufficiently robust model to predict the in vivo gastric stability of CBD, and the findings in each case may be a product of the various experimental conditions employed. The currently available and always accumulating in vivo data should be used to rule out the possibility of THC formation, especially studies where CBD is dosed at high levels. In the simplest in vivo experiment, if CBD to THC conversion takes place in stomach, one would expect to see THC in feces upon high oral dosing of the CBD. However, this has not yet been reported as both CBD and THC are excreted unchanged in the feces (vide infra).

Bioactivity of Simple CBD Analogs

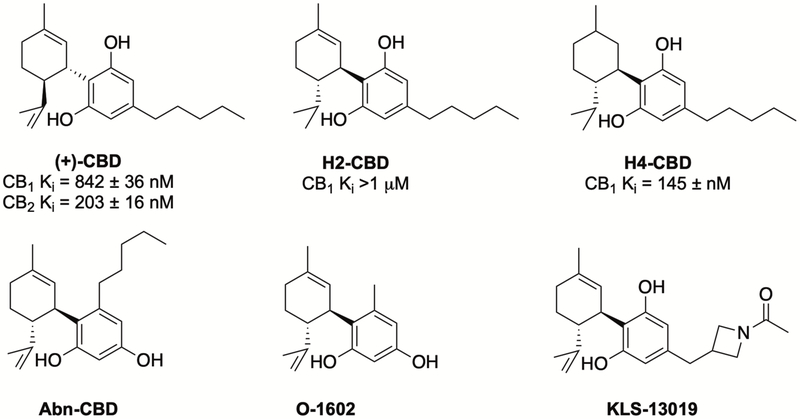

Inspired by the ethnopharmacology of Cannabis extracts, and potentially driven by reductionist research approaches (vide supra), natural (–)-CBD has attracted attention as a drug candidate and as a lead compound for medicinal chemistry campaigns. However, efforts so far have resulted in few new compounds as clinical or preclinical candidates. The large number of such studies make it impossible to review all of the results herein, but an examination of close CBD analogs will put this body of work into context. Extensive first-pass metabolism and the observed polypharmacology of CBD make it challenging to relate its therapeutic effects to a precise molecular target (vide infra). This complicates the optimization of compounds, since no one target can effectively drive structure activity relationship studies. Synthetic analogues of CBD have been targeted based on modification of the C4-alkyl chain, the phenol ring, and the limonene moiety. Biological studies of these compounds led to identification of compounds with interesting pharmacological properties (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Selected bioactive synthetic analogs of cannabidiol

Hydrogenation of the double bonds in CBD resulted in H2-CBD and H4-CBD, with reported anti-inflammatory properties, anticonvulsant properties54 and moderate affinity for the CB1 receptor.55 Unlike the naturally occurring (–)-CBD, the enantiomeric (+)-CBD is not found in nature. (+)-CBD and its analogs have been synthesized and evaluated for CB1/CB2 receptor affinity, showing strong activity below 1 μM.56,57 More interestingly, evaluation of these compounds in the tetrad group of assays58, commonly used for assessing effects on cannabinoid system, suggests that they do not activate CB1 receptors in the brain, but may have potential to selectively target the peripheral CB1 receptors for the management of peripheral pain and inflammation.57 Neuroprotective studies of C-4’ alkyl chain analogs of CBD resulted in the identification of KLS-13019 that was 50-fold more potent (40 nM vs 2 μM for CBD) and > 400-fold less toxic (Therapeutic Index of 7,500 vs 16) than CBD in preventing ammonium acetate and ethanol-induced damage to hippocampal neurons.59 A recently completed preclinical study concluded that KLS-13019 regulates the mitochondrial sodium-calcium exchanger-1 (mNCX-1), which is an important therapeutic target for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN).60 Abn-CBD, a synthetic regioisomer of CBD, and O-1602 have been reported to engage orphan receptors GPR-18 (no EC50 reported) and GPR-55 (EC50 2 nM), respectively, that are involved in diverse physiological processes.61–64

Pharmacology

CBD Receptor Activity

The broad-ranging therapeutic utility claimed of CBD has been attributed to its reported pharmacological activity at a number of receptors. Some of the most frequently highlighted targets of CBD include the following: ligand-gated ion channels (GlyR, NaV, nAch, GABAA), TRP channels (TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPA1, TRPM8), GPCRs (5-HT1A, ɑ1A, μ-OPR, δ-OPR, CB1, CB2, GPR18, GPR55), enzymes (FAAH, CYP450), and nuclear receptors (PPARg).65–67 From a careful inspection of the original publications where these bioactivities are reported, they are almost certainly irrelevant to most non-prescription products given the relatively small dose of CBD that such products contain and the low bioavailability of CBD (vide infra, Absorption). Even in the case of high-dose pharmaceutical products, some in vivo activities of CBD are only supported by brain concentrations that are achieved if CBD is dosed at 120 mg/kg in mice.68 For example, the allosteric effects reported for μ- and δ-opioid receptors was stated by the study authors not to be of significance, because the EC50 values of those interactions are approximately 100-fold higher than those of the plasma concentration of 36 ng/mL (approximately 100 nM) in humans when given a single dose of an oral preparation containing 100 mg of CBD.69 Likewise, CBD only displaced the agonist [3H]-8-OH-DPAT from the 5-HT1A receptor at EC50 8~16 μM and [3H]-ketaserin from 5-HT2A at EC50 ~32 μM.70 In the case of ion channels, it has been noted that the channel modulating effects of CBD are relatively promiscuous and may be explained by a combination of direct interaction of CBD with the channel and the impact of CBD on membrane bilayer flexibility.11,12 This is similar to the membrane disrupting effects seen with many natural products.71,72

Importantly, it is generally accepted that CBD is 50-fold less active at the endocannabinoid receptors (Ki of 4350 nM at CB1, and 2860 nM at CB2) than THC (Ki of 40.7 nM at CB1 and 36.4 nM at CB2).73 This has been used to explain the lack of psychoactive effects of CBD even at high dosing. Ironically, the observed therapeutic utility of CBD may be due to the “meaning effect” activating this placebo pathway (vide infra).74

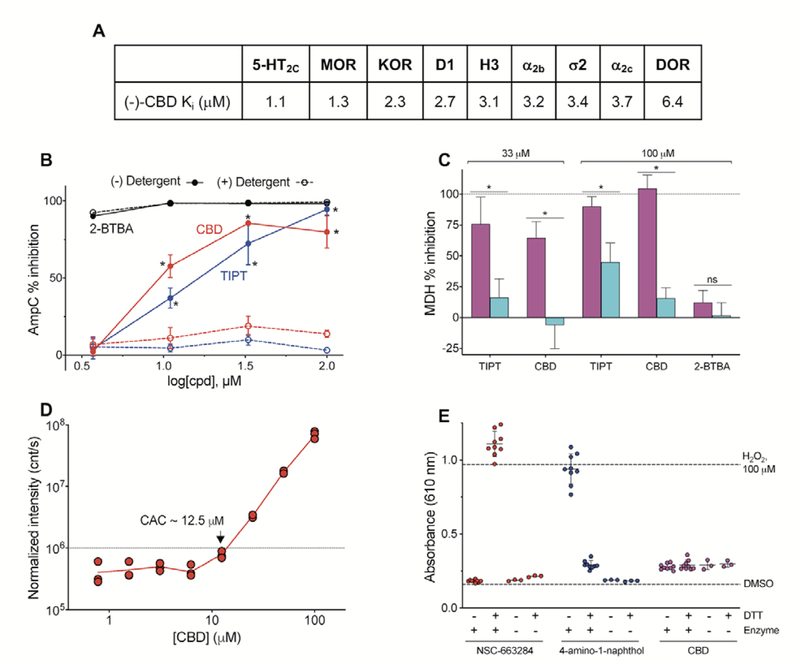

In an attempt to better understand some of the reported receptor activities of CBD, we profiled a broad panel of neurological receptors offered by the Psychoactive Drug Screening Program at UNC (Supporting Information S2). CBD did not show appreciable activity (< 50% inhibition at 10 μM) at 37 of the 45 targets assayed. It displayed measurable, but not significant, inhibition (> 50% inhibition at 10 μM) at the following receptors: 5-HT2C, MOR, KOR, D1, H3, ɑ2b, σ2, ɑ2C, and DOR (Figure 7A). CBD failed to achieve full inhibition at any of these receptors, as evidenced by dose-response curves that do not reach 0% activity at the highest concentrations tested (see Supporting Information S2). The reported Ki values for these nine receptors were all > 1 μM. Considering that pharmacological activity can only be achieved by free or unbound compound in circulation (the free drug principle75), the plasma protein binding of CBD becomes important in relation to these Ki values. CBD is reported as ~90% plasma protein bound,76 meaning that in the presence of serum proteins the Ki may be significantly higher. However, plasma protein binding alone cannot predict the relevant in vivo concentration of a compound.77 Therefore, whether or not these activities are relevant to the in vivo activity of CBD in humans remains to be further investigated.

Figure 7. Interference profiling of CBD.

(A) CBD shows moderate activity at several receptors. Ki values reported from testing by PDSP. Full data in Supporting Information. (B) CBD shows concentration-dependent, detergent-sensitive inhibition of AmpC in a colloidal aggregation counter screen. TIPT, positive aggregation control; 2-BTBA, positive non-aggregator control. Data are mean SD of four intra-run technical replicates. (C) CBD shows detergent-sensitive inhibition of MDH in an orthogonal aggregation counter screen. Compounds were tested at 33 or 100 μM final concentrations in either the presence (blue) or absence (magenta) of buffer containing freshly-added 0.01% Triton X-100 (v/v). Data are mean SD of at least three intra-run technical replicates. (D) CBD forms detectible colloidal aggregates at approximately 12.5 μM by DLS. (E) CBD does not produce detectable H2O2 in a HRP-PR redox-cycling counter screen. Compounds assayed at 250 μM final concentrations 1 mM DTT, enzyme. H2O2, positive control; NSC-663284 and 4-amino-1-naphthol, positive control compounds. Data are mean SD of at least three intra-run technical replicates.

Interaction of CBD with CYPs

The most relevant observed bioactivity of CBD as it relates to current therapeutic utility appears to be its ability to interact with CYPs. This binding has been demonstrated in numerous settings and leads to the best-documented activities of CBD, which are drug-drug interactions (DDIs) or, in the case of herbal products, drug-herb interactions (DHIs). These DDIs/DHIs cause an increase of plasma concentration of drugs that are metabolized by the CYPs, in turn generating a measurable increase in the effect of said drugs. For example, a bi-directional drug interaction occurs with the combination epilepsy medication clobazam and CBD. This results in a 1.7- to 2.2-fold increase in the mean plasma clobazam concentration in patients receiving clobazam concomitantly with 40 mg/kg/day of CBD oral solution compared with 10 mg/kg/day and 20 mg/kg/day.78

In a Phase I, open-label pharmacokinetic trial, dosing CBD concomitantly with clobazam led to an 3.4-fold increase in Cmax and AUC of N-desmethylclobazam, the major active metabolite of clobazam.10 CBD treatment of pediatric patients taking clobazam resulted in higher reporting of side effects that could be ameliorated by clobazam dose reduction.79 Finally, clinical trial simulations of the effect of 20 mg/kg/day CBD on drop-seizure frequency in patients (some of whom were also taking clobazam) with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome showed that the claimed efficacy of CBD may be largely explained by its drug-drug interaction with clobazam.80 Clobazam is primarily metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4, with minor involvement from CYP2C19 and CYP2B6.81 CBD is active at these CYPs at or below 1 μM (vide infra, Toxicology). Therefore, while CBD is an effective part of the therapy, the mechanism of action of CBD may be simply to increase the tissue concentration of another disease-modifying therapeutic. While possessing therapeutically useful properties as an adjuvant, CBD alone has not, to our knowledge, been shown to have disease-modifying effects on epilepsy or any other disease.

Bioassay interferences of CBD

CBD exhibits bioassay promiscuity. This unwanted effect is likely due to CBD’s ability to disrupt membranes and its high lipophilicity, especially when paired with high compound test concentrations in vitro (i.e., micromolar). Table 2 details several relevant physicochemical properties calculated for CBD using ChemDraw Professional 16 (PerkinElmer) and Molinspiration Property Calculation Service (v2018.10).82 Compounds can interfere with assay technologies to produce false-positive readouts, or nonspecifically perturb biological systems by poorly optimizable mechanisms of action such as redox cycling, colloidal aggregation, membrane perturbation, and general cytotoxicity, to name a few.83 This motivated the profiling of CBD for several common sources of biological assay interference as part of this study.

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties of CBD.

| |

|---|---|

| Property | Value |

| MW | 314.47 g/mol |

| Log P | 5.91 |

| ClogP | 6.64 |

| tPSA | 40.46 A2 |

| H-bond donors | 2 |

| H-bond acceptors | 2 |

| Rotatable bonds | 6 |

In our experiments (see experimental details in Supporting Information), CBD showed detergent-sensitive inhibition of two unrelated enzymes, AmpC β-lactamase and malate dehydrogenase (MDH), at low micromolar concentrations, which is consistent with nonspecific inhibition by colloidal aggregation (Figure 7B, C). CBD formed detectable colloidal aggregates by dynamic light scattering (DLS) at approximately 12.5 μM (Figure 7D; n.b. the critical aggregation concentration (CAC) can vary several-fold depending on experimental conditions). By contrast, CBD did not produce detectable levels of H2O2 in a counterscreen for redox-activity (Figure 7E). These data suggest that CBD likely forms colloidal aggregates at low micromolar concentrations, which is significant as aggregators can nonspecifically perturb proteins in both cell-free and cellular assays. Along with the noted effects of CBD on in vitro cellular health (e.g., cytotoxicity, pro-apoptotic), this calls into question how to interpret and practically apply studies that attribute specific bioactivities to CBD when testing concentrations were near the approximate CAC (or within ranges that may adversely perturb cellular health).11,84,85

In our experience with chemical probe validation, tantalizing readouts and pharmacological models produced under these conditions can be reproduced by a variety of bad-acting compounds, pointing to a nonspecific mechanism of action. In addition, these experiments can lack relevance as the in vitro conditions would never be achieved in vivo. Cell-based activity should always be accompanied by biomarker evidence of target engagement. Given its ability to injure cells, we would recommend future in vitro studies characterize the effects of CBD on cellular health in parallel to activity studies.

ADMET: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicology

Due to the diverse nature of the routes of administration by which CBD has been studied, its pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis is more complex than for other therapeutics. In addition to the traditional oral (i.e., capsule) and parenteral (i.e., intravenous) routes, CBD has also been studied as oral sublingual drops, oromucosal spray, or as a component of a food product; and as an inhalation agent through an aerosol, nebulizer, vapor, or cigarettes. All of these varied formulations and routes of administration carry different propensities for adsorption and distribution, which then affects the rest of the measured PK characteristics of the compound.

Absorption

CBD has been studied in a wide variety of formulations, but has generally been administered orally as either a capsule, dissolved in an oil or other organic solvent, or as an oromucosal spray.15 Study doses are commonly a single dose in the 2–20 mg range, with some studies testing doses upwards of 800 mg (Table 3). The plasma Cmax generally increases with increased dose and is slightly increased in the fed vs fasted state; the Tmax is not significantly impacted by dose. Absorption appears highest upon inhalation, whether by smoking or other forms of vaporization. At the time of this article, the only rigorous bioavailability (%F) reported was in a smoking study of five male participants that reported an average bioavailability of 31%.86 When considering the differences seen in plasma concentration from oral dosing, it is expected that oral bioavailability is significantly lower. In an animal study of CBD oral bioavailability, three (3) dogs led to a %F range of 13–19%.87

Table 3.

Average CBD dose, Tmax, and Cmax for human studies of CBD administration.

| Avg dose (mg) | Avg Tmax (hr) | Avg Cmax (ng/mL) | Avg Cmax (nM) | %F (if reported) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low oral dosea | 14 ± 15 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 2.2 | 0.9 | |

| High oral doseb | 525 ± 340 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 131.9 ± 82.5 | 41.5 | |

| Inhalation dosec | 3.5 ± 5.5 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 35.3 ± 41.3 | 11.1 | 31% |

Analysis of 50 reported studies of CBD dosing that included reported plasma levels.

Dose range: 1.5–20 mg

Dose range: 100–800 mg

Dose range: 1.5–20 mg

Distribution

Complete details of bodily distribution of CBD are not readily available. In the same study as cited above on oral bioavailability, the volume of distribution of CBD upon i.v. dosing was 2,520 L.86 Several studies of volume of distribution for oromucosal spray formulations report extremely high volumes of distribution between 26,000–31,000 L.88 This data suggests that any CBD that enters systemic circulation is widely distributed throughout the tissues of the body. In a study of CBD oral dosing in mice, 120 mg/kg resulted in a range of maximum brain tissue concentrations of 4–21 μM.89 Another study looked at the concentration of CBD in the brain of mice after subcutaneous administration at 10 mg/kg and reported a Cmax of 1–2 μM.68 Not surprisingly, the concentration of CBD in brain tissue is always measured as being lower than the correlating plasma concentration. Therefore, CBD levels in human brain tissue are likely to be lower than the reported plasma concentrations in humans (see Table 3, < 50 nM), however there appears to be no significant barrier to brain penetration of CBD.

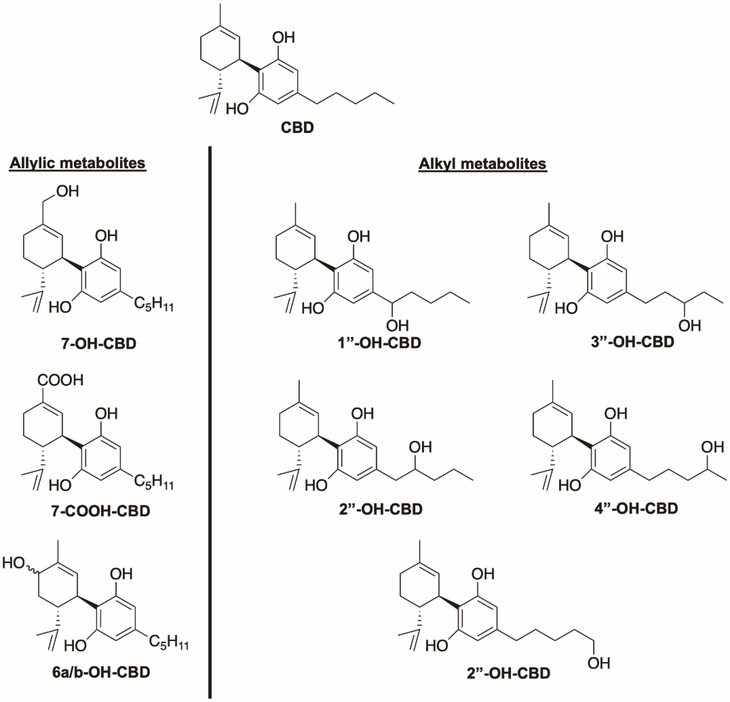

Metabolism

In general, CBD shows similar metabolism to that of THC, which aligns with their structural similarity (Figure 1A). CBD is subject to a high first-pass effect, similar to THC.90 CBD is affected by extensive oxidative metabolism, with the most prominent metabolites being allylic hydroxylation products at the 6- and 7-positions, followed by alkyl hydroxylation products at all positions along the alkyl chain (Figure 8).91,92 Several of these metabolites have been identified in human plasma,93 and at least one report of the analysis of human urine identifies these and the glucuronides of the phenolic oxygen species.94 Several in vitro studies have investigated which cytochrome P450 enzymes are primarily responsible for these transformations. The allylic hydroxylations are primarily performed by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, while the alkyl hydroxylations can be produced by a wider variety of enzymes: CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, and CYP2D6. Recent in vitro evidence showed the formation of decarbonylated metabolites via CYP3A4 activity in human liver microsomes.95 To date, no literature suggests significant receptor activity for any of these identified CBD metabolites.

Figure 8.

Major metabolites of cannabidiol.

Of great interest is the question of whether CBD can be converted to THC after dosing. While there is some contested evidence that highly acidic environments can facilitate this transformation (vide supra), no evidence in the current literature suggests that CBD is metabolized into THC in vivo.96,97,98

Excretion

The half-life of elimination (t1/2) of CBD is variable and depends especially on its route of administration. Generally, oral administration via oil, oromucosal spray, or nebulizer/aerosol leads to a t1/2 of about 2 h.99,100 Administration via i.v., smoking, or chronic oral administration leads to a significantly longer t1/2 of 24 h, 31 h,86 or 2–5 days,101 respectively.

While CBD and THC are both subject to a strong first-pass effect, a significant portion of both cannabinoids are excreted unchanged in the feces.102 This suggests that a large portion of a CBD dose is not absorbed, which matches the reports of low bioavailability.14 The families of oxidized and glucuronidated metabolites are largely excreted by the kidneys and can be identified in the urine.

The overall plasma clearance of CBD varies depending on the fed vs. fasted state. Oromucosal spray administration of doses ranging from 5–20 mg yields apparent plasma clearance (CL’) ranging from 2,500–4,700 L/h.88,103,104 This decreases to 533 L/h for the same concentration range in a fed state.103 In contrast, the mean elimination rate (Kel) does not change significantly between the fed and fasted states. There is some variation in elimination rate depending on the route of administration. Oromucosal spray administration results in Kel (1/h) values ranging from 0.12–0.17. Nebulizer or aerosol administration, however, result in Kel values of of 0.98 and 0.43, respectively.99

Toxicology

CBD appears to generally be safe upon administration via several routes at low doses (< 100 mg). However, studies of CBD use in combination with other drugs, and animal toxicological studies, raise concerns of DDIs and other potential adverse effects.

As the metabolism of CBD has been well-studied (vide supra), the administration of CBD when taking drugs that are known to inhibit or activate relevant cytochrome P450s will alter the overall plasma concentration and/or half-life of CBD in the plasma. In addition, CBD has been shown to inhibit some cytochrome P450 enzymes at physiologically achievable levels (Table 4).105 Importantly, CBD interferes with the metabolism of both hexobarbital106 and, as presented earlier, clobazam79 if given concomitantly, raising concerns for drug-drug interactions (DDIs).

Table 4.

In vitro inhibition of CYP activity by CBD.105

| CBD Ki (μM) | |

|---|---|

| CYP1A1 | 0.16 |

| CYP1A2 | 2.69 |

| CYP1B1 | 3.63 |

| CYP2A6 | 55.0 |

| CYP2B6 | 0.69 |

| CYP2C9 | 5.60 |

| CYP2C11 | 20.7 |

| CYP2C19 | 0.79 |

| CYP2D6 | 2.42 |

| CYP3A4 | 1.00 |

| CYP3A5 | 0.19 |

| CYP3A7 | 12.3 |

| CYP17 | 124 |

More recently, several studies have been published warning about potential adverse effects of CBD administration, as determined through cellular or animal studies. In 2017, the hypothesis that CBD can be neuroprotective in neonatal hypoxic-ischemia was tested in pigs. High-dose (25 or 50 mg/kg) CBD resulted in significant hypotension (mean arterial blood pressure drop below 70% of baseline), including death by fatal cardiac arrest in at least one animal. In addition, no neuroprotective effect was observed in this model as measured by neuropathology, astrocytic markers, and other plasma markers.107 In 2018, the pattern of DNA methylation in the sperm of cannabis users was found to be significantly altered, and overall sperm concentration was significantly lower as compared to non-users.108 These changes were similar to the shift in epigenetic patterns seen in THC-exposed rats, which raises the concern for possible inheritable epigenetic changes related to cannabis use.109 It is not known whether chronic use of CBD alone can lead to epigenetic changes.

Research into the reproductive toxicity of chronic CBD exposure in male mice corroborates the potential reproductive toxicity.110 The authors report that 34 days of 15 or 30 mg/kg daily dosing resulted in significant changes in several measures of reproductive health, including: testosterone levels, spermatogenesis, daily sperm production, and increased abnormal sperm morphology. A 2019 study aimed at determining the potential hepatotoxicity of CBD evaluated gene expression arrays in mice after oral dosing of a single high dose (246–2460 mg/kg) or chronic lower dose (61.5–615 mg/kg for 10 days) of CBD.111 In this study, gene expression arrays showed alteration of > 50 genes following CBD dosing, relating to oxidative stress responses, lipid metabolism pathways, and drug metabolizing enzymes. Finally, a study of CBD exposure in two human-derived cell lines showed nuclear aberrations and DNA damage consistent with single and double strand breaks and apurinic sites.112 This cellular damage was observed at CBD concentrations (0.22 μM) that are relevant to reported CBD exposure in humans.

Clinical trials

From a thorough analysis of the literature, it appears that CBD has not shown efficacy as a single substance in any Phase II or III clinical trials. In Phase I trials, CBD has been shown to be generally well-tolerated at single doses up to 6000 mg and multiple doses up to 1500 mg twice daily.93 The most common side-effects were gastrointestinal disorders, headaches, and somnolence. CBD has advanced to Phase III clinical trials in certain rare forms of epilepsy. In the pivotal Phase III clinical trials (multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled) that led to the approval of Epidiolex®, all patients were typically taking at least three other seizure medicines along with CBD: clobazam (47–51%), valproate (all forms, 37–39%), levetiracetam (30–32%), lamotrigine (26–33%), or rufinamide (26–34%) (name of the medication, percent of patients taking the drug across all arms of the trial).113 In this trial, the median percent reduction from baseline in drop-seizure frequency was 42% in the 20 mg/kg/day group (the average age of study participant was 15 y.o., ~1000 mg/day) and 17% in the placebo group.

Although this result was in part responsible for the approval of Epidiolex® in these hard-to-manage forms of epilepsy, the significance of this result with respect to the pharmacological action of CBD has been called into question. This is because of known DDIs between CBD and other anti-epileptic drugs,114 which is especially relevant in the case of clobazam and its active metabolite, N-desmethylclobazam. CBD doses of 20 mg/kg/day (as were used in the Epidiolex® trial) are known to increase the exposure of N-desmethylclobazam 2- to 6-fold in children with refractory epilepsy despite clobazam dose reductions.79 This, and other evidence, led Groeneveld to propose that the effect of CBD on drop-seizure frequency may be explained solely on this DDI, without the need to invoke any special epilepsy-treating pharmacology to CBD.80,115 The American Epilepsy Society had the following to say about these clinical trials (quoted here for clarity):

“Recently, there have been several scientifically rigorous, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials of one specific pharmaceutical-grade, purified, highly concentrated CBD for patients with refractory epilepsy that have been published. Studies evaluating the pharmacokinetics and potential drug-drug interactions with this formulation have also been published or presented at epilepsy congresses. These trials demonstrated that this one pharmaceutical-grade CBD is moderately effective in the treatment of patients with seizures in both Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS) and Dravet syndrome. However, these studies also showed that CBD has more side effects than placebo and revealed previously unrecognized drug-drug interactions.”116

We found several examples of CBD being touted as a remedy for addiction,117 aging,118 anxiety, arthritis,119 concussion,120 depression, nausea, obesity,121 pain, Parkinson’s disease,122 post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychiatric disorders (among others).117 However, no evidence of double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trials that supported these claims could be located. One double-blinded trial, albeit not placebo-controlled, in patients with schizophrenia reported a clinically-significant reduction in PANSS scores (Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale) of patients treated with 800 mg/day. In this case, the quality of the CBD used in the trial was not reported.123

Anecdotal claims of CBD therapeutic utility often arise from what are actually inconclusive studies. For example, some claims of the therapeutic utility of CBD are based on studies where the substance being tested was actually cannabis (extract) rather than CBD; in other studies the size of the trial was too small to make any conclusive judgements; and in still others the patients were taking other medications that may be subject to CBD DDIs. Therefore, it remains blurred whether any clinical trials have shown CBD alone to be effective for therapeutic use. Claims to the contrary must ensure the relevance of the referenced clinical trial by qualifying the following points:

What was the exact identity and purity of the CBD used? Note that APIs are distinct from crude preparations (such as plant extracts), and that Residual Complexity (including significant content in, e.g., THC; vide supra) is relevant and will confound the study results.

Was the trial placebo-controlled?

Was the trial double-blinded?

Was the statistical analysis plan published before the trial?124

Did the authors claim significance of the results?

If CBD was used in combination, was the possibility of DDIs considered? Is the co-administered agent metabolized by CYPS?

It is also important to note that the effective CBD doses used in most reported clinical trials are typically 800–1000 mg/day. Putting this into the perspective, commercial “tinctures” or “oils” commonly found in the marketplace consist of less than 20 mg CBD per serving. A typical consumer-sized bottle of CBD oil (30 mL) might contain 1000 mg total CBD and cost on the order of $50–60.125

With respect to anecdotal reports of efficacies of CBD oils and tinctures, such CBD “personal trials” may be subject to a “placebo” response based on the cachet of CBD as a well-known component of (medical) cannabis. The intricate influence of the placebo effect on the testing of cannabis and cannabinoids has been discussed; e.g. Gertsch wrote recently:13 “Unlike with other medicinal plants that have rather questionable efficacies and unknown mechanisms of action, nobody seems to doubt a priori the therapeutic effectiveness of cannabis. Accordingly, patients who use medical cannabis products have high expectations of beneficial effects (i.e., the plant is meaningful to them).” and “Rather than being either a placebo or drug, cannabis might be a drug both conveying and inducing a meaning response.” The anthropologist, David Moerman, referred to this effect of the conveyed meaning embodied in the placebo as the “meaning response”.126 Therefore, because CBD has been so conflated with cannabis, even if CBD has no direct pharmacological effect, its associated “meaning effect” may activate a secondary pharmacological effect. Ironically, this meaning effect in CBD trials may occur via the endocannabinoid CB1 and CB2 pathways, receptors for which CBD has no intrinsic activity, though are the primary mediators of THC’s effects.13,127 Clinical trials of botanical preparations fail to reject the placebo-based null hypothesis128 and report unexpectedly pronounced placebo effects129,130 more commonly than API-based trials, which further supports the relevance of “meaning responses” and “meaning effects”.

Summary

Cannabis is a useful therapeutic and source of lead compounds. At the same time, the reductionist tendencies of Western medicine have seen certain Cannabis preparations reduced to the pure compound, CBD. While this study could not find evidence supporting the numerous and broad health claims associated with CBD, evidence suggests that CBD can affect biological systems in the following ways: (a) through a strong, physiologically-relevant interaction with metabolizing enzymes, thereby modulating the activity of other substances; (b) via a strong “meaning effect”, and (c) by means of a weak, promiscuous, and low-level modulation of membrane-bound proteins.

The recent FDA approval of CBD as a drug excludes it from being used as a dietary supplement in the U.S. If used at low doses, e.g., as one (minor) constituent of supplements, which often carry the potentially misleading “CBD” label, CBD most likely cannot produce any therapeutic effect. When used at high doses, any therapeutic effect is likely due to either the strong interaction of CBD with metabolic enzymes, its likely “meaning effect”, or a result of other components contained in products labeled as “CBD”. Additionally, at the highest doses, negative side-effects are likely to become more pronounced, thereby limiting the utility of this substance.

Unless the purity of CBD is assessed rigorously, or whenever a chemically complex (crude) material is the component of a product bearing the “CBD” label, Residual Complexity can become a major disruptor in the logical chain that connects CBD as an API and pharmacological agent with its role as the key active component of the preparation: residually complex materials have a much increased chance of containing other, especially minor and/or more potent bioactives.

While many claims have been made about a large variety of potential health benefits of CBD, the present work uncovers a lack of scientific foundation to most of these claims. While CBD can enter systemic circulation at potentially physiologically relevant levels, there is no clear understanding of the receptor activity of CBD, and an even greater deficiency in terms of potentially harmful adverse effects. Whereas an FDA-approved therapeutic regimen containing CBD does exist, the efficacy of the treatment appears to be related to its DDI mechanisms. Importantly, unless new biological targets for antiviral and/or health resilience can be discovered and validated, product claims that CBD has health effects for treatment or alleviation of SARS-CoV-2 and analogous viral pathogens should be considered unsubstantiated and misguided.131

Widely available products with chemically complex ingredients containing various amounts of CBD are a major confounding factor in distinguishing sound experimental evidence, including clinical trials and other in vivo outcomes, from unsubstantiated or anecdotal health claims. This observation reflects a concerning global trend of obscuring the lack of quality control parameters and objective health outcomes of freely available products by associating them with the word “natural” and similarly implicative terms. More rigorous work needs to be done to determine what, if any, specific efficacy CBD may have as a therapeutic agent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Ki determinations, receptor binding profiles, agonist and/or antagonist functional data, HERG data, MDR1 data, etc. as appropriate was generously provided by the National Institute of Mental Health’s Psychoactive Drug Screening Program, Contract # HHSN-271-2018-00023-C (NIMH PDSP), directed by Dr. Bryan L. Roth at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Project Officer Jamie Driscoll at NIMH, Bethesda MD, USA. The authors acknowledge the following financial support: JLD through grant T32 HL007627 from NHLBI/NIH; JB, JGG, SNC, and GFP through grants U41 AT008706 and P50 AT000155 jointly from ODS/NIH and NCCIH/NIH. Furthermore, the authors acknowledge the collegial spirit of Drs. Young-Hae Choi and Rob Verpoorte, University of Leiden, for kindly sharing their historic raw NMR data. JLD gratefully acknowledges Drs. Parnian Lak and Brian Shoichet for performing DLS experiments. Finally, the authors thank Ms. M Backmann for help in creating the figure for the graphical abstract.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The opinions or assertions contained herein belong to the authors and are not necessarily the official views of the funders.

Abbreviations Used

- CBD

cannabidiol

- DDI

drug-drug interaction

- DHI

drug-herbal interaction

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- HiFSA

1H iterative full spin analysis

- IMPs

invalid metabolic panacea

- OTC

over-the-counter

- THC

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

Biographies

Kathryn M. Nelson is a Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Institute for Therapeutics Discovery & Development (ITDD) at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. After obtaining a PhD in Medicinal Chemistry from the University of Minnesota, she was a postdoctoral associate before becoming a Research Assistant Professor in Medicinal Chemistry at the ITDD. Her work has focused on target discovery, validation, and lead molecule development for new targets in neurodegenerative diseases. She has also expanded her expertise to the development of biomarker assays for new targets in anticipation of preclinical evaluation.

Jonathan Bisson obtained an M.S. degree in structural biochemistry and started his phytochemistry journey under the mentorship of Dr. Vincent Dumontet at the Institut de Chimie des Substances Naturelles, Gif-sur-Yvette, France. He then obtained a PhD in Science, Technology and Health from the University of Bordeaux, France under the mentorship of Dr. Pierre Waffo-Téguo, specializing in methodology at the chemistry-biology interface and practicing liquid-liquid chromatography, NMR spectroscopy, and hyphenated techniques. In 2013, he joined the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he is currently a Visiting Research Assistant Professor, developing software tools, ontologies and preparative and analytical methods for natural products research in interdisciplinary programs.

Gurpreet Singh is a Senior Scientist at the Institute for Therapeutics Discovery and Development (ITDD) at the University of Minnesota (UMN), USA. He received his Master’s degree in chemistry from Guru Nanak Dev University (GNDU) at Amritsar (India), and joined Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Limited at Hyderabad (India) as a medicinal chemist where he contributed to the anti-infective program. In 2015, he obtained his PhD in Medicinal Chemistry from the University of Kansas (KU) at Lawrence, Kansas (USA). During his doctoral research, he developed alkaloid natural product-inspired libraries for the discovery of biological probes, and synthetic routes for the synthesis of enantioenriched cyclic-1,3-diols. Currently his research is focused on the discovery of new chemical probes and drugs for neurodegenerative diseases.

James G. Graham is a Research Assistant Professor in the Department Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy. After obtaining a PhD in Pharmacognosy in Chicago, he received an NIH postdoctoral fellowship in Miami and worked as Technical Officer at the World Health Organization in Geneva. In 2007 he returned to Chicago to work as a protege of Norman R. Farnsworth on his NAPRALERT (NAtural PRroduct ALERT) database, of which he is currently editor, as well as serving as Assistant Program Director, Program for Collaborative Research in the Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Shao-Nong Chen obtained his Ph.D. in Organic Chemistry from Lanzhou University, then undertook two years of post-Ph.D. training at the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica (SIMM) before joining Dr. Sydney Hecht’s group at the University of Virginia in 1999 as a research fellow. He moved to UIC in 2000, where he currently is an Associate Research Professor, working on botanical standardization and integrity in the UIC/NIH Botanical Center, as well as on method development for the analysis of bioactive natural products in interdisciplinary programs. He developed “chemical subtraction”, NMR-based Natural Product Mining methods, and “dynamic residual complexity” concepts. He co-authored 140+ peer-reviewed articles and two book chapters.

J. Brent Friesen is a professor of chemistry in the Rosary College of Arts and Sciences at Dominican University. He earned his PhD in natural products chemistry at the University of Minnesota with Eddie Leete. He is the author or co-author of nearly 50 scientific publications. His role in the development of countercurrent separation methodologies and technologies has helped to revolutionize the practice of countercurrent separation. These methodologies include pioneering work in elution-extrusion countercurrent chromatography, reciprocal symmetry plots, the Generally Useful Estimation of Solvent Systems (GUESS), optimization of countercurrent separation parameters, and the development of the phase metering apparatus. Currently, he is involved with biomedical research that will advance the application of countercurrent separation technologies to improve the isolation and characterization of bioactive compounds.

Jayme L. Dahlin is currently a Clinical Fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. He earned his B.A. (chemistry) from Carleton College (MN), his Ph.D. in Molecular Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics from Mayo Graduate School, and his M.D. from Mayo Medical School. He recently completed a clinical residency in clinical pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where he also served as Chief Resident. He is now board-certified in clinical pathology and is currently performing chemical biology research in the laboratories of Stuart L. Schreiber and Bridget K. Wagner at the Broad Institute. His current research interests include high-throughput screening and assay development.

Matthias Niemitz is a serial entrepreneur with more than 25 years of experience in quantum mechanical NMR spectral analysis, grew up in Germany and received his chemistry degree at the Free University Berlin. He joined the NMR group at the University of Kuopio, Finland and established the PERCH NMR Software project. In 2001 he incorporated PERCH Solutions, a company that was bought by Bruker BioSpin in 2009. After Bruker closed PERCH Solutions, the former management and employees of PERCH incorporated a new company, NMR Solutions.

Michael A. Walters is a Research Associate Professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Minnesota (UMN). He began his academic career in the Department of Chemistry at Dartmouth College and then worked at Parke-Davis and Pfizer. He is currently the Director of the Lead and Probe Discovery Group in the Institute for Therapeutics Discovery and Development at the UMN. This institute serves as a mini-biotech for the development of the ideas of biomedical researchers at the UMN and Mayo Clinic. His research interests currently focus on the investigation of compound reactivity as it applies to assay interference mechanisms, the development of Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics, and cheminformatics and computer assisted drug design.

Guido F. Pauli is a pharmacist with a doctoral degree in natural products chemistry and pharmacognosy. As Norman R. Farnsworth Professor of Pharmacognosy and Distinguished Professor at UIC, Chicago (IL), he directs and collaborates in various interdisciplinary natural product-driven research projects. He develops bioanalytical methodology for active principles from complex natural products from plant and microbial metabolomes, with applications in anti-TB drug discovery, dental health, dietary supplements, and pharmaceutical quality control. Scholarly activities involve the education of the next generation of pharmac(ognos)ists; service on pharmacopoeial expert, federal agency and NGO panels; journal board functions; international collaborations and exchange; and active dissemination with currently 220+ peer-reviewed journal articles.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting information is available free of charge and includes: quantum-mechanical 1H NMR characterization of CBD using HiFSA, psychoactive drug screening program activity of CBD, and pharmacological methods for evaluation of CBD.

References

- (1).Cannabidiol Market Size Analysis | CBD Industry Growth Report, 2025 https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/cannabidiol-cbd-market (accessed Apr 22, 2020).

- (2).Dorbian I CBD Market Could Reach $20 Billion By 2024, Says New Study. Forbes Magazine Forbes May 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Nelson KM; Dahlin JL; Bisson J; Graham J; Pauli GF; Walters MA The Essential Medicinal Chemistry of Curcumin. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60 (5), 1620–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Dietz BM; Chen S-N; Alvarenga RFR; Dong H; Nikolić D; Biendl M; van Breemen RB; Bolton JL; Pauli GF DESIGNER Extracts as Tools to Balance Estrogenic and Chemopreventive Activities of Botanicals for Women’s Health. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 2284–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Yang Y; Zhang Z; Li S; Ye X; Li X; He K Synergy Effects of Herb Extracts: Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamic Basis. Fitoterapia 2014, 92, 133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Caesar LK; Cech NB Synergy and Antagonism in Natural Product Extracts: When 1 + 1 Does Not Equal 2. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36, 869–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Friesen JB; Liu Y; Chen S-N; McAlpine JB; Pauli GF Selective Depletion and Enrichment of Constituents in “Curcumin” and Other Curcuma longa Preparations. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 621–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zuardi AW; Crippa JAS; Hallak JEC; Moreira FA; Guimarães FS Cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa Constituent, as an Antipsychotic Drug. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2006, 39, 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Mogil JS Laboratory Environmental Factors and Pain Behavior: The Relevance of Unknown Unknowns to Reproducibility and Translation . Lab Anim. 2017, 46, 136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Morrison G; Crockett J; Blakey G; Sommerville K A Phase 1, Open-Label, Pharmacokinetic Trial to Investigate Possible Drug-Drug Interactions Between Clobazam, Stiripentol, or Valproate and Cannabidiol in Healthy Subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug. Dev. 2019, 8, 1009–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ghovanloo M-R; Shuart NG; Mezeyova J; Dean RA; Ruben PC; Goodchild SJ Inhibitory Effects of Cannabidiol on Voltage-Dependent Sodium Currents. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 16546–16558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Watkins AR Cannabinoid Interactions with Ion Channels and Receptors. Channels 2019, 13, 162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Gertsch J The Intricate Influence of the Placebo Effect on Medical Cannabis and Cannabinoids Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2018, 1, 60–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).WHO CBD Report May 2018 CANNABIDIOL (CBD) Critical Review Report https://www.who.int/medicines/access/controlled-substances/WHOCBDReportMay2018-2.pdf?ua=1 (accessed Oct 25, 2019).

- (15).Millar SA; Stone NL; Yates AS; O’Sullivan SE A Systematic Review on the Pharmacokinetics of Cannabidiol in Humans. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Office of the Commissioner. What to Know About Products Containing Cannabis and CBD https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/what-you-need-know-and-what-were-working-find-out-about-products-containing-cannabis-or-cannabis (accessed Apr 23, 2020).

- (17).Gaoni Y; Mechoulam R Hashish—VII: The Isomerization of Cannabidiol to Tetrahydrocannabinols. Tetrahedron 1966, 22, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Gutman AL; Etinger M; Fedotev I; Khanolkar R Methods for Purifying Trans-(−)-Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Trans-(+)-Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol. U.S. Patent 8,383,842, 2006.

- (19).Aizpurua-Olaizola O; Soydaner U; Öztürk E; Schibano D; Simsir Y; Navarro P; Etxebarria N; Usobiaga A Evolution of the Cannabinoid and Terpene Content during the Growth of Cannabis sativa Plants from Different Chemotypes. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Basas-Jaumandreu J; de Las Heras FXC GC-MS Metabolite Profile and Identification of Unusual Homologous Cannabinoids in High Potency Cannabis sativa. Planta Med. 2020, 86, 338–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Luo X; Reiter MA; d’Espaux L; Wong J; Denby CM; Lechner A; Zhang Y; Grzybowski AT; Harth S; Lin W; Lee H; Yu C; Shin J; Deng K; Benites VT; Wang G; Baidoo EEK; Chen Y; Dev I; Petzold CJ; Keasling JD Complete Biosynthesis of Cannabinoids and Their Unnatural Analogues in Yeast. Nature 2019, 567, 123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kumari S; Pundhir S; Priya P; Jeena G; Punetha A; Chawla K; Firdos Jafaree Z; Mondal S; Yadav G EssOilDB: A Database of Essential Oils Reflecting Terpene Composition and Variability in the Plant Kingdom. Database 2014, 2014, bau120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Degenhardt F; Stehle F; Kayser O The Biosynthesis of Cannabinoids In Handbook of Cannabis and Related Pathologies. Biology, Pharmacology, Diagnosis, and Treatment; Preedy VR, Ed.; Elsevier: London, 2017; pp 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Pauli GF; Chen S-N; Simmler C; Lankin DC; Gödecke T; Jaki BU; Friesen JB; McAlpine JB; Napolitano JG Importance of Purity Evaluation and the Potential of Quantitative 1H NMR as a Purity Assay. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9220–9231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Martin Emanuele R; Shattock-Gordon T; Williford T; Andres M; Andres P New Solid Forms of Cannabidiol and Uses Thereof. World Intellectual Property Organization. WO2019118360A1, 2019.

- (26).Mechoulam R; Hanuš L Cannabidiol: An Overview of Some Chemical and Pharmacological Aspects. Part I: Chemical Aspects. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2002, 121, 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]