Abstract

Instructive feedback (IF) is a strategy for increasing the efficiency of targeted instruction. Previous research has demonstrated the success of IF with learners with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), but limited research exists regarding the efficacy of the intervention with individuals with ASD who engage in vocal stereotypy. The effects of 2 forms of IF were examined with a learner with ASD who engaged in vocal stereotypy. In Study 1, no intervention for vocal stereotypy was implemented. In Study 2, response interruption and redirection (RIRD) was implemented contingent on vocal stereotypy. IF before the praise statement resulted in faster acquisition of secondary targets, but only when RIRD was implemented. These results extend the IF literature by providing evidence that individuals who engage in vocal stereotypy may require concurrent intervention to increase the opportunity for indiscriminable contingencies to be established and the acquisition of secondary targets via IF.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Indiscriminable contingencies, Instructive feedback, Vocal stereotypy

Instructive feedback (IF) is a teaching procedure where nontargeted information (i.e., secondary targets) is presented during direct instruction of explicitly targeted skills (primary targets; Werts, Wolery, Holcombe, & Gast, 1995). For example, if an instructor presents a primary target during a teaching interaction (e.g., labeling a picture of a car), after the learner labels the picture, the instructor may introduce additional information into the consequent event of the teaching trial as a secondary target (e.g., cars have wheels). Previous research has demonstrated positive effects of IF with learners with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Vladescu & Kodak, 2013) in both one-to-one (e.g., Nottingham, Vladescu, & Kodak, 2015) and group (e.g., Leaf et al., 2017) instructional formats across a variety of contexts, including language (Tullis, Frampton, Delfs, & Shillingsburg, 2017), academic skills (Werts, Hoffman, & Darcy, 2011), and play (Grow, Kodak, & Clements, 2017).

Despite the evidence that IF procedures have been effective in improving instructional efficiency, the mechanisms that facilitate the emergence of secondary targets without explicit instruction remain unclear (Albarran & Sandbank, 2018). One hypothesis is that the occurrence of indiscriminable contingencies—environmental events where antecedents or consequences for responses are less salient (Stokes & Osnes, 1989)—may play a role (Nottingham, Vladescu, Kodak, & Kisamore, 2017; Vladescu & Kodak, 2013). Although some evidence exists that is supportive (e.g., Loughrey, Betz, Majdalany, & Nicholson, 2014), these projects have not specifically tested for the presence of indiscriminable contingencies.

In a recent investigation, Tullis, Gibbs, Butzer, and Hansen (2019) investigated the potential for indiscriminable contingencies to be one mechanism at strength during IF procedures with two children diagnosed with ASD. In one condition, the IF statement was presented prior to the praise statement, and in the second, IF was presented after the praise statement. For example in the IF before condition, the participant engaged in a correct response (e.g., “Tiger.”) then the IF stimulus was delivered before the praise statement (e.g., “Tigers have tails. Nice work!”), and in the after condition, the participant engaged in the primary response (e.g., “Tiger.”), then IF was delivered after the praise statement (e.g., “That’s right! Tigers have tails.”). Across conditions, mastered targets were the primary stimulus, and novel stimuli were the secondary targets. This arrangement allowed for greater isolation of the effects of IF placement. For both participants, IF presented prior to the praise statement resulted in faster secondary target acquisition, indicating that indiscriminable contingencies may be one possible mechanism responsible for the effectiveness of IF procedures, because reinforcement did not directly follow the IF statement. This type of procedure is similar to those proposed previously to program for generalization of directly taught responses, where delayed reinforcement that is presented for correct responses facilitates responding to novel targets (e.g., Baer, Williams, Osnes, & Stokes, 1984).

In addition to the lack of information related to mechanisms of IF, questions remain related to the efficacy of this procedure with people with ASD who engage in some intervening responding. Recent studies have hypothesized that the occurrence of vocal stereotypy may impede the effectiveness of IF procedures. For example, Tullis et al. (2017) investigated the effects of IF procedures to teach verbal problem-solving skills to three participants with ASD. For one participant, IF procedures alone resulted in the acquisition of secondary targets. For the remaining participants, more explicit teaching procedures were necessary for the emergence of secondary targets. One source for this difference in acquisition was hypothesized to be the occurrence of vocal stereotypy at differing levels as measured by the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program Barriers Assessment (Sundberg, 2008).

The efficacy of IF procedures with individuals with ASD who also engage in vocal stereotypy is unclear (Tullis et al., 2017), and research with this section of the population of individuals with ASD is limited. Previous research has demonstrated that the presence of stereotypy in children with ASD can interfere with skill acquisition (e.g., Chebli, Martin, & Lanovaz, 2016), and recent research demonstrates that vocal stereotypy may interfere with the emergence of secondary targets via IF procedures (Tullis et al., 2017). Taken together, the presence of vocal stereotypy may prevent learners from acquiring secondary targets because vocal stereotypy prevents indiscriminable contingencies from emerging. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to replicate and extend the Tullis et al. (2019) investigation with a learner with ASD who also engaged in vocal stereotypy.

General Method

Participant

Luke was an 8-year-old, White male who had been diagnosed with ASD by an independent physician. At the time of the study, Luke received speech and occupational therapy once per week, as well as 9 hr of applied behavior analysis. Since the age of 3, Luke had received between 8 and 10 hr per week of behavioral intervention. Luke communicated vocally using one- to three-word phrases, though he was able to utilize full sentences to make requests given indirect prompts (e.g., an adult looking away and not acknowledging his request until he emitted a full sentence). Based on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition (Sparrow, Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005), Luke’s adaptive behavior composite was low, categorized as a mild deficit. As measured by both the Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition (Martin & Brownell, 2011b), and the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition (Martin & Brownell, 2011a), Luke’s receptive language skills were in the 2nd percentile with an age equivalent of 5 years, and splintered skills ranging from 6 years through 9 years, whereas his expressive language skills were below the 1st percentile with an age equivalent of 3 years, 11 months, and splintered skills ranging from 4 years through 9 years. Upon evaluation with the VB-MAPP (Sundberg, 2008), Luke was classified as a Level 2 learner with established Level 3 listener, visual performance/match to sample, math, reading, and writing skills and emerging Level 3 skills in manding, tacting, and listener responding by function, feature, and class. As measured by the VB-MAPP Barriers Assessment, Luke demonstrated elevations on 19 out of the 24 barriers, with the highest scored barriers being self-stimulation and sensory defensiveness.

Setting and Materials

All sessions were conducted in private treatment rooms within the outpatient clinic where Luke received direct therapy. Rooms were approximately 4.6 m × 3.4 m and were equipped with at least one table, chairs, cabinets of therapeutic materials, and bookcases and/or shelves with therapeutic materials occluded by a cloth cover. During experimental sessions, the experimenter and participant sat at an individual table, though there were occasionally other children who were not participants in the current investigation working with therapists at other tables in the room.

Experimental materials included two sets of 12.7 cm ×10.16 cm stimulus cards. Stimulus cards consisted of a color stimulus mounted on a white background, and multiple exemplars were used for each stimulus. Target stimuli sets were selected in consultation with Luke’s behavior analyst. Each set contained three stimuli that shared a common feature or were members of the same class, and each stimulus had been previously trained as a tact—but not as a receptive function, feature, or class (RFFC) target—within Luke’s therapeutic programming (see Table 1). Additionally, a whiteboard and dry erase marker were used to implement a token system for Luke during sessions. Data collection materials included a paper data sheet, a pencil, and an iPad mini for video recording.

Table 1.

Stimuli and RFFC Designation for Studies 1 and 2

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Set 1 |

IF Before Television |

IF Before Toothbrush |

| Vacuum | Shampoo | |

|

Lamp (Feature: Cord) |

Soap (Class: Toiletry) |

|

| Set 2 | IF After | IF After |

| Apple | Bag | |

| Leaf | Hairbrush | |

| Flower | Saw | |

| (Feature: Stem) | (Feature: Handle) |

Response Definitions and Measurement

Correct primary responses (tacts) were vocal responses that had been directly taught to Luke in the presence of their corresponding stimuli (e.g., saying “hairbrush” in the presence of a hairbrush stimulus card). Correct secondary responses (RFFC) were either physical card touches or vocal responses to receptive instructions (e.g., touching the soap stimulus card or saying “soap” when directed to “find the one that is a toiletry”). Secondary responses were considered correct only if the response matched the IF provided during primary response trials. The percentage of correct independent responses was measured by dividing the number of correct responses by the total number of trials within the session and multiplying by 100. Mastery criteria were three consecutive sessions with 100% responding during secondary target probes.

Vocal stereotypy was defined as any instance of contextually inappropriate vocalization lasting at least 3 s. This included singing, laughing, babbling, or saying words or phrases unrelated to the present situation. An occurrence of vocal stereotypy ended when Luke was quiet and attending or responding to the experimenter for 3 s. Vocal stereotypy was measured from the video footage of the session using duration-per-occurrence recording. Observers activated a stopwatch upon the occurrence of vocal stereotypy and stopped the stopwatch contingent on the absence of stereotypy as previously described. The duration was recorded on a data sheet, and the stopwatch was reset. The duration of each occurrence of vocal stereotypy was recorded in this manner for the entirety of the session video, and the total duration of vocal stereotypy (in seconds) was calculated by summing all individual occurrences together. The proportion of sessions with vocal stereotypy was calculated by dividing the total duration of vocal stereotypy by the total duration of the session and multiplying by 100.

Interobserver Agreement and Procedural Fidelity

Study 1

A second trained observer scored data for an average of 36% (range 33% to 40%) of sessions in all conditions from video recordings. Interobserver agreement (IOA) for primary and secondary targets was calculated by totaling the number of agreements (i.e., trials in which both observers scored the same response), then dividing the number of agreements by the total number of trials and multiplying the quotient by 100. Agreement across both primary and secondary responses was 99% (range 83%–100%). Data on the duration of vocal stereotypy were collected post hoc from session videos, and agreement was 88% (range 78%–95%). Procedural fidelity data were also collected for an average of 36% of sessions in all conditions for Study 1 (range 33%–40%). Fidelity was measured using a structured data sheet to document the occurrence of each implementation step in each condition. Accurate performance was required on all steps for a trial to be correctly implemented. Procedural fidelity for primary and secondary target session procedures was 100% across all conditions.

Study 2

IOA was scored for an average of 35% (range 33%–40%) of sessions across baseline, intervention (including best treatment), and maintenance conditions. The same IOA calculation procedure for primary and secondary targets as used in Study 1 was used during Study 2. IOA for vocal stereotypy was calculated using total duration, in which the smaller duration was divided by the larger duration and multiplied by 100. Agreement for primary responses averaged 99% across all conditions (range 89%–100%) and 99% across all conditions for secondary responses (range 83%–100%). Agreement for vocal stereotypy averaged 93% across all conditions (range 79%–100%). Procedural fidelity data were collected for an average of 35% (range 33%–40%) of sessions in all conditions using the same procedure as used in Study 1. Fidelity was also collected on the implementation of response interruption and redirection (RIRD) when Luke engaged in vocal stereotypy. Procedural fidelity for primary and secondary target session procedures was 100% across all conditions, with RIRD fidelity averaging 96% across all conditions (range 83%–100%).

Experimental Design

An adapted alternating-treatments design (Ledford & Gast, 2014) was used to compare the effects of delivering IF before praise to the effects of delivering IF after praise on the acquisition of secondary targets. Targets were assigned to sets based on logical analysis of syllables, and all sets contained targets that were one to three syllables in length. A best treatment phase was introduced after differentiation was observed between each data path, indicating that one variation resulted in greater skill acquisition.

Study 1

Procedure

This study consisted of two conditions: baseline and intervention. Across all conditions, one session was conducted per day, with sessions taking place 4 days per week, and all sessions were conducted by a doctoral student with a current Board Certified Behavior Analyst certification (second author). During both baseline and intervention, a session included primary target trials and secondary target probes, with 30 min elapsing between session components. During all intervention sessions, IF was delivered during primary target trials. A token system that was previously validated as an effective intervention was used during sessions for compliance with mastered targets interspersed between trials and probes only. Tokens were used as a consequence for engaging in mastered targets alone to prevent token delivery from interfering with the potential effects of IF placement and praise, and were delivered on a variable ratio 3 schedule.

Baseline

Primary and secondary target sessions were conducted separately. Six trials occurred per session. For primary responses, Luke was shown the stimulus card and the experimenter provided the instruction for him to respond (e.g., “What is it?”). Social praise was provided following all responses whether they were correct or incorrect, and mastered targets were interspersed following one to four probes. No IF of any kind was given during baseline primary target sessions. During secondary target sessions, the experimenter placed an array of five mastered and novel stimulus cards in front of Luke and provided an instruction for him to indicate which card was part of a specific class (e.g., “Find the one that is a toiletry.”) or had a specific feature (e.g., “Which one has a handle?”). Social praise was provided following each trial regardless of correct or incorrect responding, and mastered targets (e.g., listener responding, tact, and intraverbal targets) were interspersed following one to four probes. Baseline sessions continued until responding was steady across both sets of stimuli.

IF before

Primary target trials were conducted using the same procedure as was used in baseline; however, contingent on correct responding, IF with the corresponding secondary target information was given, followed by a praise statement (e.g., “What is it?” “Lamp.” “A lamp has a cord. Nicely done!”). If Luke emitted an incorrect response or did not respond, the experimenter vocally delivered the initial instructional cue (e.g., “What is this?”), immediately provided the primary target information (e.g., “It’s a fox.”), and, contingent on the correct response (e.g., Luke stating “fox”), delivered IF followed by a praise statement (e.g., “Foxes have tails. That’s right!”). Three trials were conducted per stimulus for a total of nine primary target + IF trials. At the conclusion of the primary target trials, a timer was set for 30 min, and Luke’s typical therapeutic skill acquisition programs were run. Once 30 min had elapsed, secondary target probes were conducted using the same procedure used during baseline. Three probes were conducted per stimulus for a total of nine secondary target probes.

IF after

Sessions were the same as those during the IF before condition, with the exception of IF delivery. Contingent on a correct response to a primary target trial, a praise statement was given, followed by IF with the corresponding secondary target information (e.g., “What is it?” “A flower.” “That’s right! A flower has a stem.”). If no response was emitted, or the response was incorrect, error correction was initiated as stated previously, and IF was delivered following a correct response. After all primary target + IF trials had been completed, and 30 min had elapsed, secondary target probes were run.

IF + differentiated praise

Procedures remained identical to those during IF before for Set 1 and IF after for Set 2; however, following an incorrect response during a secondary target probe, the experimenter delivered a neutral statement (e.g., “Okay.”), whereas social praise continued to be provided for correct secondary target responses.

Results

Luke’s primary target responses met mastery criteria during baseline and maintained at mastery level throughout intervention (data available upon request). Figure 1 depicts Luke’s percentage of correct secondary target responses during experimental sessions. During baseline probe sessions, Luke demonstrated low accuracy (M = 10%, range 0%–33%). Despite an initial increase upon initiating intervention, Luke’s correct responding exhibited a downward trend across both the IF before (M = 22%, range 11%–33%) and IF after (M = 33%, range 22%–44%) conditions. After implementing the use of differentiated praise during secondary target probes, Luke’s correct responding moderately increased for both conditions (M = 44.2%, range 22%–67% for IF before; M = 46.2%, range 33%–55% for IF after), but differentiation between the data paths did not occur, and mastery criteria were never achieved in either IF condition.

Fig. 1.

Results from Study 1. The percentage of correct secondary responses in the IF before condition are represented by the filled circles, whereas the percentage of correct secondary responses in the IF after condition are represented by the open circles

Figure 2 displays Luke’s proportions of sessions with vocal stereotypy across conditions during Study 1. The proportion of baseline sessions with vocal stereotypy was low (M = 9.01%, range 2.18%–19.46%). Vocal stereotypy decreased slightly during IF after sessions (M = 4.67%, range 0%–9.71%) and increased somewhat during IF before sessions (M = 12.11%, range 3.69%–26.82%). Similar proportions were seen during both conditions following the use of differentiated praise during secondary target probes (M = 10%, range 4.12%–20.01% for IF after; M = 11.08%, range 6.05%–14.79% for IF before).

Fig. 2.

Results from Study 1. The proportions of sessions in the IF before condition with vocal stereotypy are represented by the filled circles, whereas the proportions of sessions in the IF after condition with vocal stereotypy are represented by the open circles

Discussion

The purpose of Study 1 was to determine if secondary targets emerged with IF procedures alone. Some acquisition of secondary targets was observed across IF presentations, but neither condition resulted in mastery. Previous research on vocal stereotypy has demonstrated that the presence of competing vocal responses (i.e., stereotypy) may interfere with the acquisition of directly taught vocal targets (Chebli et al., 2016), and varying levels of intervention may be necessary before skill acquisition occurs (Cook & Rapp, 2020). More recent IF research demonstrates that vocal stereotypy may interfere with the emergence of secondary targets via IF procedures (Tullis et al., 2017).

Although the literature supports the assertion that the presence of stereotypic responses interferes with directly taught targets, little empirical information is available related to the acquisition of secondary targets, or those that are not directly taught. RIRD (Ahearn, Clark, MacDonald, & Chung, 2007) is a consequence-based intervention implemented contingent on the occurrence of vocal stereotypy, in which a learner is required to emit several consecutive vocal responses without engaging in stereotypy, with social reinforcement provided for appropriate vocalizations. RIRD had previously been successful in reducing Luke’s vocal stereotypy and was implemented contingent on the occurrence of stereotypy during his regular therapy sessions. Thus, in Study 2, the procedure comparing the effects of the secondary target location during IF that was implemented in Study 1 was replicated with the addition of RIRD contingent on vocal stereotypy across all conditions.

Study 2

Procedure

During Study 2, all baseline, IF before, and IF after procedures remained identical to those of Study 1, with the following exception. RIRD (Ahearn et al., 2007), which was an established intervention for Luke’s vocal stereotypy, was implemented contingent on Luke engaging in vocal stereotypy during any session across all conditions. A previous functional analysis (Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1994) indicated that vocal stereotypy was maintained by automatic reinforcement (data available upon request). RIRD consisted of immediately interrupting Luke’s vocal response, getting his attention by stating his name while initiating eye contact, and introducing demands to spell three- to four-letter words (e.g., cat, mom, girl). On the infrequent occasions in which motor stereotypy occurred simultaneously with vocal stereotypy, the experimenter issued a brief statement (e.g., “Get control.”) after gaining Luke’s attention to redirect motor stereotypy before introducing vocal demands for RIRD. If 5 s elapsed without a correct response, or Luke continued to engage in vocal stereotypy, the experimenter stated the correct answer and reissued the demand (e.g., “Spell ‘dog.’ [5 s elapses] D-o-g. Spell ‘dog.’”). If Luke again did not emit the correct response or continued to engage in vocal stereotypy, the experimenter issued a new demand. Three consecutive correct responses were required to end the RIRD procedure, at which point Luke was directed back to the task he had been engaged in prior to the occurrence of stereotypy.

Best treatment phase

Once steady, differentiated responding indicated that one IF variation was resulting in greater skill acquisition than the other, a best treatment phase was implemented for the primary target + IF trials with both sets of stimuli, utilizing the procedure associated with the more effective form of IF. During this condition, if Luke engaged in echoic behavior during primary target trials (e.g., “What is it?” “A bag has a handle.”), a correction was provided, though the trial was still considered to be correct.

Maintenance probes

Once Luke reached mastery criteria for one set of stimuli, the set entered maintenance. A maintenance session consisted of three secondary target probes utilizing the same procedure used during baseline sessions. The maintenance probes for each set spanned 16 to 17 weeks, and the length of time between each probe increased according to a set schedule (i.e., four probes/week [Set 2 only], three probes/week, two probes/week, one probe/week, biweekly probe, probe every 3 weeks, probe once per month). Ten maintenance probes were conducted for Set 1, and 14 maintenance probes were conducted for Set 2.

Social Validity

At the conclusion of the intervention, Luke’s mother was given a description of the intervention, viewed labeled graphs, and was shown video clips of Luke during baseline and intervention. She then filled out a Treatment Evaluation Inventory (TEI; Kelly, Heffer, Gresham, & Elliot, 1989) for the IF variation that resulted in greater skill acquisition. The questionnaire was composed of a set of statements that Luke’s mother responded to using a Likert scale, with 1 equaling strongly disagree and 5 equaling strongly agree, and mean acceptability was calculated from her responses, with the score given to Item 6 adjusted to address the issue of reverse scoring (e.g., if Item 6 was rated a 1, strongly disagree, this was reversed to a 5 for calculating mean acceptability).

Results

Luke’s primary target responses met mastery criteria during baseline probes. However, during the IF comparison phase, he demonstrated variability in his responding. Once the best treatment condition was implemented, Luke’s primary responses immediately reached and remained at 100% for the entirety of the condition and throughout maintenance (data available upon request).

Figure 3 depicts Luke’s percentage of correct secondary target responses during experimental sessions and maintenance probes. Prior to intervention, Luke demonstrated stable responding with low accuracy across both sets of stimuli (M = 17%). Once intervention was initiated, correct responding immediately increased for Set 1 during the IF before condition (M = 67%, range 22%–78%). In contrast, correct responding for Set 2 in the IF after condition never improved (M = 15%, range 0%–22%). Despite Set 1 not reaching mastery criteria during the comparison phase, the best treatment phase with the IF before procedure was implemented following six sessions in each condition based on the level of differentiation between the two data paths. During the best treatment phase, Set 1 reached mastery criteria within three sessions, and the percentage of correct responding for Set 2 quickly increased, meeting mastery criteria within six sessions. Luke maintained correct responding at 100% for the entirety of the maintenance phase for Set 1 and correct responding at an average of 97.6% (range 67%–100%) for Set 2.

Fig. 3.

Results from Study 2. The percentage of correct secondary responses in the IF before condition are represented by the filled circles, whereas the percentage of correct secondary responses in the IF after condition are represented by the open circles

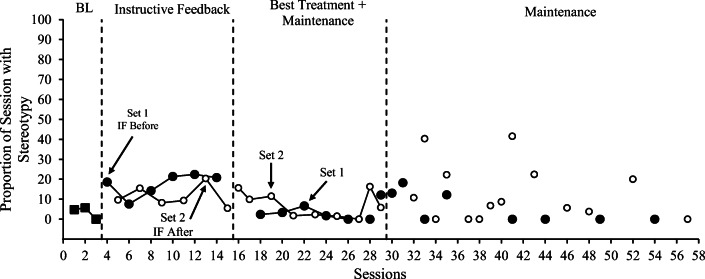

Figure 4 displays Luke’s duration of vocal stereotypy across conditions. Stereotypy was brief during baseline sessions (M = 3.55%, range 0%–5.78%). Upon initiating the IF comparison phase, the proportion of sessions with stereotypy increased above baseline levels, with larger proportions seen during the IF before condition for Set 1 (M = 17.55%, range 7.6%–22.44%) as compared to the IF after condition for Set 2 (M = 11.44%, range 5.46%–20.39%). Once both sets of stimuli entered the best treatment phase, the proportions of sessions with vocal stereotypy for Set 1 immediately decreased and remained low for the duration of the phase (M = 2.85%, range 0%–6.65%). The proportions of sessions with vocal stereotypy for Set 2 also decreased, but at a slower rate (M = 7.21%, range 0%–16.36%). Throughout the maintenance phase, proportions of sessions with vocal stereotypy during probes for Set 1 remained low (M = 5.58%, range 0%–18.31%) but was highly variable during probes for Set 2 (M = 13.04%, range 0%–41.58%).

Fig. 4.

Results from Study 2. The proportions of sessions in the IF before condition with vocal stereotypy are represented by the filled circles, whereas the proportions of sessions in the IF after condition with vocal stereotypy are represented by the open circles

Table 2 contains the questions and ratings from Luke’s mother on the TEI (Kelly et al., 1989) for IF before, as this was the IF variation that resulted in increased skill acquisition. Luke’s mother rated the intervention favorably and expressed interest in the application of IF within Luke’s typical skill acquisition programming, as well as interest in participation in future studies evaluating the use of IF with children who engage in stereotypy.

Table 2.

TEI Questions and Parent Ratings for IF Before Procedures

| Question | Rating |

|---|---|

| 1. I find this intervention to be an acceptable way of addressing my child’s skill acquisition. | 5 |

| 2. I would be willing to use this intervention at home to address my child’s skill acquisition. | 5 |

| 3. I believe that it would be acceptable to use this intervention without my child’s consent. | 5 |

| 4. I like the procedures used in this intervention. | 5 |

| 5. I believe this intervention is effective for my child. | 5 |

| 6. I believe that my child experiences discomfort during this intervention. | 1 |

| 7. I believe this intervention is likely to result in permanent improvement in my child’s learning. | 5 |

| 8. I believe that it would be acceptable to use this intervention with children who cannot choose interventions for themselves. | 5 |

| 9. Overall, I have a positive reaction to this intervention. | 5 |

Note. Items were rated on a Likert-type scale of 1–5 with 1 indicating strongly disagree, 3 indicating neutral, and 5 indicating strongly agree. Item 6 was reverse scored.

Discussion

During Study 2, a decrease in stereotypic behavior was observed consistent with previous research on RIRD procedures (e.g., Ahearn et al., 2007), and a clear differentiation in acquisition was observed in the IF before and after conditions. The interruption of vocal stereotypy may have increased the likelihood that the primary target response came under the control of the contingencies present in the teaching context, and a collateral effect may have been an increase in the salience of the IF stimuli. The acquisition of secondary targets via IF may have been the result of stimuli being presented without a response requirement, similar to how reducing stereotypy may result in increases in other responses when noncontingent reinforcement is delivered (Lanovaz, Robertson, Soerono, & Watkins, 2013), which led to an indiscriminable contingency being formed.

General Discussion

In the current investigation, results from Tullis et al. (2019) were replicated and extended to a learner who engaged in vocal stereotypy. During Study 1, IF alone was unsuccessful for the participant to acquire secondary responses, supporting previous research that demonstrated that the presence of vocal stereotypy can interfere with the acquisition of secondary targets via IF procedures (Tullis et al., 2017). In Study 2, when RIRD was implemented contingent on vocal stereotypy, IF provided before the praise statement resulted in faster acquisition of secondary responses, replicating the findings of Tullis et al. (2019).

One possibility for this finding is that the presence of competing responses minimized the acquisition of secondary targets when IF procedures alone were implemented without also intervening on vocal stereotypy (Chebli et al., 2016; Cook & Rapp, 2020). During Study 1, vocal stereotypy was not directly addressed during intervention sessions. However, during Luke’s regular skill acquisition programs outside of IF sessions, RIRD was implemented contingent on Luke engaging in vocal stereotypy. This may have created a situation in which IF intervention sessions came to function as an establishing operation for vocal stereotypy (Lanovaz, Rapp, Long, Richling, & Carroll, 2014). However, this seems unlikely, as Luke’s proportions of sessions with stereotypy during Study 1 were similar to those seen in Study 2.

A more likely possibility is that the effect of multiple contingencies during Study 2 played a role in Luke’s responding. Lanovaz et al. (2013) reported that the combination of differential reinforcement and a punishment contingency may not only reduce engagement in stereotypy but also increase engagement in appropriate behaviors. During Study 1, reinforcement for correct responses was provided via vocal praise, whereas vocal stereotypy was ignored. During Study 2, Luke continued to receive reinforcement for correct responses via vocal praise, with the addition of punishment via RIRD contingent on engaging in vocal stereotypy. This potentially created a situation in Study 2 in which Luke’s responding came under the control of the differential consequences that were present. RIRD has been demonstrated to increase the occurrence of appropriate vocalizations (Ahearn et al., 2007; Ahrens, Lerman, Kodak, Worsdell, & Keegan, 2011), and there exists the possibility that this had a facilitative effect on secondary target acquisition in Study 2.

In Study 2, greater proportions of vocal stereotypy were recorded during sessions in the IF comparison phase as compared to Study 1, decreasing once the best treatment phase was initiated. Previous research suggests that skill acquisition may have an indirect effect on vocal stereotypy (Colón, Ahearn, Clark, & Masalsky, 2012; Pierce & Schreibman, 1994). As the best treatment phase was initiated once the IF before condition resulted in greater target acquisition, vocal stereotypy may have decreased as a positive collateral effect of skill acquisition in combination with the suppressive effects of RIRD (Colón et al., 2012). Although these findings are interesting and deserving of additional investigation, they are beyond the scope of the current study, which sought to evaluate the effect of secondary target location during IF procedures. Future research should look more closely at the combined effects of IF and RIRD on secondary target acquisition in learners with vocal stereotypy.

Previous investigations in the IF literature have hypothesized that a generalized imitative repertoire, among other mechanisms, may facilitate secondary target acquisition (Nottingham et al., 2015; Tullis et al., 2017), and the occurrence of echoic behavior during instruction with IF procedures (e.g., restating the IF stimulus) has been reported in several studies (Haq, Zemantic, Kodak, LeBlanc, & Ruppert, 2017; Vladescu & Kodak, 2013). In the current investigation, Luke did not emit any echoic responses during Study 1. During Study 2, echoic responses did occur, but only during sessions in the IF after condition, and this had a suppressive effect on skill acquisition. Once the best treatment phase was initiated, echoic behavior during primary target trials resulted in a correction, which decreased the occurrence of echoic responses, and an increase in correct responding. Although overt echoic behavior during IF had a negative impact on secondary target acquisition, this does not exclude the potential occurrence of covert echoic responding, in which Luke (the listener) covertly echoed what he heard, making future responses more probable (Schlinger, 2008). Further explanation of the potential effects of covert verbal behavior is presented in previous work (e.g., Tullis et al., 2017; Tullis, Marya, & Shillingsburg, 2018) and will not be discussed here, but these data provide further support for the utility of additional research into the effects of covert and overt verbal repertoires on emergent learning.

In the current investigation, the results of Tullis et al. (2019) were replicated in part and extended to a learner who engaged in vocal stereotypy, but three main limitations warrant consideration and may serve as areas of further research. First, the mechanisms responsible for secondary target acquisition are not fully known (Nottingham et al., 2015; Werts et al., 1995). The current study provides some additional support for the consideration of indiscriminable contingencies playing a role in acquisition, but additional sources, such as the role of the demand context, cannot be ruled out. In the current investigation, all sessions occurred in Luke’s typical intervention context with therapists who were familiar to him and who had a history of reinforcing his attending and responding. A full discussion of the potential mechanisms underlying IF procedures has been presented elsewhere (e.g., Nottingham et al., 2015) and is beyond the scope of the current article, but future research should seek to further isolate the proposed mechanisms underlying acquisition via IF for evaluation alone and in combination.

Second, the current study presented expansion IF, as opposed to parallel or novel IF (Werts et al., 1995). Expansion IF may create conditions where the primary and secondary targets become related as a function of acquisition via indiscriminable contingencies. In comparison, other forms of IF (i.e., novel IF) may be due to other potential mechanisms (e.g., demand context). Previous work has demonstrated that a relation between stimuli is not necessary for secondary target acquisition (Werts, Caldwell, & Wolery, 2003). It is unknown if this process would yield the same results for stimuli that are not as clearly related. Future research should compare the acquisition of secondary targets before and after the praise statement in a learning trial when using parallel or novel IF.

Third, generalization to novel stimulus arrangements was not tested in the current investigation. Additional stimulus relations may emerge following mastery of primary and secondary targets. For example, following acquisition of a tact (e.g., “Saw.”), then acquiring a receptive skill by feature as a secondary target (e.g., “It has a handle.”), a novel relation (e.g., intraverbal fill-in) may emerge. In the current investigation, therapists working with Luke reported generalization anecdotally, but the lack of explicit evaluation of the emergence of untaught relations is an area deserving of future inquiry.

Overall, the results of the current investigation are supportive of the efficacy of IF procedures with learners with ASD and extend the literature to a learner who engages in vocal stereotypy. These results provide further preliminary support for indiscriminable contingencies potentially being one of several processes (e.g., demand context, incidental learning) resulting in secondary target acquisition from IF. Further research is necessary to fully explore these mechanisms in individuals with ASD with and without vocal stereotypy to more fully account for the processes underlying effective learning via IF procedures and to better understand how vocal stereotypy affects these processes.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Research Highlights

• Highlights the utility of instructive feedback for learners with ASD and vocal stereotypy;

• Demonstrates the necessity of treating vocal stereotypy if skill acquisition is impeded;

• Provides support for at least one mechanism underlying the effectiveness of IF, but only if competing responses are reduced; and

• Demonstrates a method for probing for maintenance of both primary and secondary targets.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahearn WH, Clark KM, MacDonald RP, Chung BI. Assessing and treating vocal stereotypy in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:263–275. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.30-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens, E. N., Lerman, D. C., Kodak, T., Worsdell, A. S., & Keegan, C. (2011). Further evaluation of response interruption and redirection as treatment for stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 95–108. 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Albarran SA, Sandbank MP. Teaching non-target information to children with disabilities: An examination of instructive feedback literature. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2018;28:107–140. doi: 10.1007/s10864-018-9301-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Williams JA, Osnes PG, Stokes TF. Delayed reinforcement as an indiscriminable contingency in verbal/nonverbal correspondence training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1984;17:429–440. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1984.17-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chebli SS, Martin V, Lanovaz MJ. Prevalence of stereotypy in individuals with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;3:107–118. doi: 10.1007/s40489-016-0069-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colón CL, Ahearn WH, Clark KM, Masalsky J. The effects of verbal operant training and response interruption and redirection on appropriate and inappropriate vocalizations. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45:107–120. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J. L., & Rapp, J. T. (2020). To what extent do practitioners need to treat stereotypy during academic tasks?. Behavior Modification, 44, 228–264. 10.1177/0145445518808226. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grow LL, Kodak T, Clements A. An evaluation of instructive feedback to teach play behavior to a child with autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2017;10:313–317. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0153-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq SS, Zemantic PK, Kodak T, LeBlanc B, Ruppert TE. Examination of variables that affect the efficacy of instructive feedback. Behavioral Interventions. 2017;32:206–216. doi: 10.1002/bin.1470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M. F., Slifer, K. J., Bauman, K. E., & Richman, G. S. (1994). Toward a functional analysis of self???injury. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 27, 197–209. 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kelly ML, Heffer RW, Gresham FM, Elliot SN. Development of a modified treatment evaluation inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1989;11:235–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00960495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lanovaz MJ, Robertson KM, Soerono K, Watkins N. Effects of reducing stereotypy on other behaviors: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013;7(1234):1243. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lanovaz MJ, Rapp JT, Long ES, Richling SM, Carroll RA. Preliminary effects of conditioned establishing operations on stereotypy. The Psychological Record. 2014;64:209–216. doi: 10.1007/s40732-014-0027-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf JB, Cihon JH, Alcalay A, Mitchell E, Townley-Cochran D, Miller K, et al. Instructive feedback embedded within group instruction for children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2017;50:304–316. doi: 10.1002/jaba.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledford, J. R., & Gast, D. L. (Eds.). (2014). Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences. New York: Routledge.

- Loughrey TO, Betz AM, Majdalany LM, Nicholson K. Using instructive feedback to teach category names to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47:425–430. doi: 10.1002/jaba.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin NA, Brownell R. Expressive one-word picture vocabulary test. 4. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Martin NA, Brownell R. Receptive one-word picture vocabulary test. 4. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nottingham CL, Vladescu JC, Kodak TM. Incorporating additional targets into learning trials for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48:227–232. doi: 10.1002/jaba.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottingham CL, Vladescu JC, Kodak T, Kisamore AN. Incorporating multiple secondary targets into learning trials for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2017;50:653–661. doi: 10.1002/jaba.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KL, Schreibman L. Teaching daily living skills to children with autism in unsupervised settings through pictorial self-management. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:471–481. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger HD. Listening is behaving verbally. The Behavior Analyst. 2008;31:145–161. doi: 10.1007/BF03392168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., & Balla, D. A. (2005). Vineland adaptive behavior scales (Vineland II): Survey interview form/caregiver rating form. Livonia, MN: Pearson Assessments.

- Stokes TF, Osnes PG. An operant pursuit of generalization. Behavior Therapy. 1989;20:337–355. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(89)80054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML. Verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program: The VB-MAPP. Concord, CA: AVB Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tullis CA, Frampton SE, Delfs CH, Shillingsburg MA. Teaching problem explanations using instructive feedback. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2017;33:64–79. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullis CA, Gibbs AR, Butzer M, Hansen SG. A comparison of secondary target location in instructive feedback procedures. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2019;3:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s41252-018-0090-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vladescu JC, Kodak TM. Increasing instructional efficiency by presenting additional stimuli in learning trials for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:805–816. doi: 10.1002/jaba.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werts MG, Wolery M, Holcombe A, Gast DL. Instructive feedback: Review of parameters and effects. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1995;5:55–75. doi: 10.1007/bf02110214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werts MG, Caldwell NK, Wolery M. Instructive feedback: Effects of a presentation variable. Journal of Special Education. 2003;37:124–133. doi: 10.1177/00224669030370020601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werts MG, Hoffman EM, Darcy C. Acquisition of instructive feedback: Relation to target stimulus. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2011;46:134–149. [Google Scholar]