Abstract

We conducted a functional analysis to identify the specific features of feet responsible for evoking inappropriate sexual behavior (ISB) by an adolescent male with autism. Results showed that bare female and male feet evoked ISB. We then evaluated a treatment consisting of a rule describing appropriate and inappropriate behavior in the presence of bare feet and a verbal reprimand contingent on ISB; the combination of these was effective. Finally, as an additional treatment option, we evaluated an environmental enrichment procedure, which also reduced ISB to low levels.

Keywords: Autism, Behavioral assessment, Fetish, Inappropriate sexual behavior

A fetishistic disorder is diagnosed when an individual experiences sexual urges focused on a nongenital body part or inanimate object. The individual must then act on these urges and experience some distress due to this action (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Fetishistic disorder should be distinguished from fetishistic behavior that causes no distress to the individual experiencing the fetish or others; in fact, fetishistic behavior may be a harmless form of sexual activity (APA, 2013). Fetishistic behavior may be problematic, however, when it occurs in public and when its focus involves mere acquaintances, as opposed to sexual partners. Behavioral interventions may be the first choice of intervention to treat problematic fetishistic behavior because they produce fewer side effects than medical treatments.

Individuals with autism and related disabilities, who often experience communication and other difficulties, may be more likely than the general population to exhibit inappropriate sexual behavior (ISB; Schöttle, Briken, Tüscher, & Turner, 2017). In some cases, this ISB may involve problematic fetishistic behavior. To date, only one case study has described ISB involving a fetish exhibited by an individual with autism. Dozier, Iwata, and Worsdell (2011) provide a model for assessing and treating problematic fetishistic behavior. These authors first conducted a functional analysis to identify the specific stimuli that evoked ISB in a man with a foot fetish. The results suggested that the sight of women’s feet in sandals evoked public masturbation. The authors then evaluated two treatments, sensory extinction and response interruption / time-out, to reduce ISB. In the sensory-extinction treatment, the participant wore an athletic cup to protect his genitals; the cup minimized sensory stimulation when the participant gyrated his pelvis on the floor (p. 135). In the response interruption / time-out treatment, the participant wore a backpack. Contingent on ISB, the experimenter interrupted the response by lifting up on the backpack straps, which prevented genital contact with the floor. Sensory extinction was ineffective, but response interruption / time-out was effective to decrease the behavior to low levels.

Although response interruption / time-out was effective in Dozier et al. (2011), this treatment may be considered intrusive. In the current study, we replicated Dozier et al. with an adolescent male with autism who exhibited ISB. We first conducted an A-B functional analysis (Carr & Durand, 1985) to identify the specific features of feet that evoked problematic behavior. We then evaluated a rule/reprimand treatment and an environmental enrichment treatment to decrease ISB. We evaluated two separate treatments because each may be most appropriate for different contexts.

Method

Setting and Participant

We conducted the study at a children’s hospital in Central Florida. Larry, the participant, was a 12-year-old boy with a diagnosis of autism. He spoke in short sentences and could follow multiple-step instructions. Larry exhibited sexual behavior in public; this included touching his genitals outside of his clothing and gyrating his genitals against hard surfaces. This behavior had resulted in ridicule from peers, and Larry’s parents and teachers were concerned that his social problems would worsen. Informant assessment and descriptive observations suggested that these behaviors were maintained by automatic reinforcement; they occurred in the absence of social consequences. The specific stimuli that occasioned Larry’s public sexual behavior were unclear, although descriptive observations suggested that he often stared at other people’s feet prior to or when engaging in ISB.

We conducted four to six sessions per day, 2–3 days per week, in therapy rooms at the children’s hospital. All sessions were 5 min in duration. The therapy rooms included a single chair; no toys or other stimuli were available, and nothing was on the walls.

Data Collection and Interobserver Agreement

We collected data on the percentage of intervals with ISB, defined as Larry touching his own genital area or pressing his genital area against the chair or floor. Trained observers recorded the occurrence of ISB on laptop computers while observing live sessions via a camera. We divided each session into 5-min intervals; observers used partial-interval recording to collect data.

To collect interobserver agreement (IOA) data, a second independent observer recorded data for 100% of sessions during the functional analysis, 100% of sessions during the rule/reprimand treatment evaluation, 100% of sessions during the competing-stimulus assessment, and 89% of sessions during the environmental enrichment treatment evaluation. IOA was determined by comparing data from two observers on an interval-by-interval basis. An agreement was scored when both observers recorded the occurrence or nonoccurrence of ISB for a given interval. The number of intervals with agreement was then divided by the total number of intervals (30) in each session. Finally, we calculated a mean agreement score by averaging agreement scores across sessions. Mean IOA was 100% for all assessment and treatment evaluation conditions.

Procedure

Functional Analysis

We conducted an A-B functional analysis (i.e., we manipulated antecedents only) to identify features of feet that evoked Larry’s ISB. We used a multielement design to compare six conditions during the functional analysis; each condition was conducted five times. The conditions were (a) woman with shoes, (b) woman without shoes, (c) man with shoes, (d) man without shoes, (d) alone in the room with shoes, and (e) alone in the room. During all conditions, the therapist was seated on the floor with his or her legs extended before Larry entered the room. The therapist wrote long pants that exposed only the ankles and feet. When Larry entered the room, the therapist said, “Hi, Larry. I need to finish some work on my phone. You can do whatever you like while you wait for me.” The therapist did not look at Larry or respond to Larry after this statement. During the woman (or man) with shoes conditions, a woman (or man) was in the room with Larry; the woman (or man) wore shoes that completely covered her (or his) feet. In the conditions without shoes, the same woman (or man) was in the room with bare feet. During the alone in the room with shoes condition, Larry was alone with a pair of gender-neutral shoes, which were placed on the floor in the center of the room. The therapist told Larry, “I need you to wait in this room while I talk to someone for a few minutes. I will get you when we finish.” Larry confirmed that he understood the contingency by saying “okay” and walking into the room. During the alone in the room condition, Larry was in the room by himself with no shoes present, and the therapist said the same statement described in the alone in the room with shoes condition. Larry had met the woman and man who were present in the sessions, which included another person, but did not interact with them regularly.

Rule/Reprimand Treatment Evaluation

We used a concurrent multiple-baseline design across therapists (female and male) to evaluate two interventions. Baseline sessions were identical to the woman (or man) without shoes conditions described previously. The same therapists who conducted the functional analysis conducted this evaluation. The first intervention was a rule, which took the form of the following statement: “If you touch your privates or press your privates against the floor, then I will be very unhappy.” The rule was given once by each therapist at the beginning of the first session of the rule intervention condition. It was not given in subsequent sessions during this phase. The therapist said nothing else to Larry during sessions. The second intervention consisted of the reprimand “No touching (or pressing) privates” and was delivered in a sharp tone by the therapist on a fixed ratio 1 schedule. At the beginning of the first session of this phase (but never thereafter), each therapist also delivered the rule described previously. The therapist said nothing else to Larry during any session.

Competing-Stimulus Assessment

Larry’s parents were uncomfortable instructing some of Larry’s peers to deliver the reprimand described previously. They requested an alternative intervention that could be used in situations in which Larry’s peers were present. Thus, we conducted an assessment to determine tangible items that might compete with ISB (Fisher, DeLeon, Rodriguez-Catter, & Keeney, 2004). Three items were evaluated: an iPad (on which Larry watched age-appropriate videos), a book, and a toy snake. These items were first identified by Larry’s parents as preferred, and a subsequent paired-stimulus preference assessment (Fisher et al., 1992) confirmed that they were Larry’s three most preferred items (data not shown). During the competing-stimulus assessment, a female therapist with no shoes on was in the room with Larry (the same therapist conducted all sessions). The therapist was not the same person who conducted the functional analysis or treatment evaluation described previously. The therapist did not interact with Larry. One of the three items described previously was also in the room, but no other stimuli were available. We collected data on the percentage of intervals with ISB and appropriate item interaction during each session. We conducted five sessions per condition.

Environmental Enrichment Treatment Evaluation

To further evaluate the effects of competing stimuli and to compare exposure of these items to a baseline condition, we conducted a brief environmental enrichment treatment evaluation. During these sessions, the same female therapist who conducted the competing-stimulus assessment was in the room with Larry but did not interact with him. The therapist wore no shoes. Baseline sessions were identical to baseline sessions in the rule/reprimand treatment evaluation described previously. After baseline, we provided noncontingent access to the toy snake, the book, and the iPad (one per condition) in a multielement format. We also conducted an additional baseline probe.

Results and Discussion

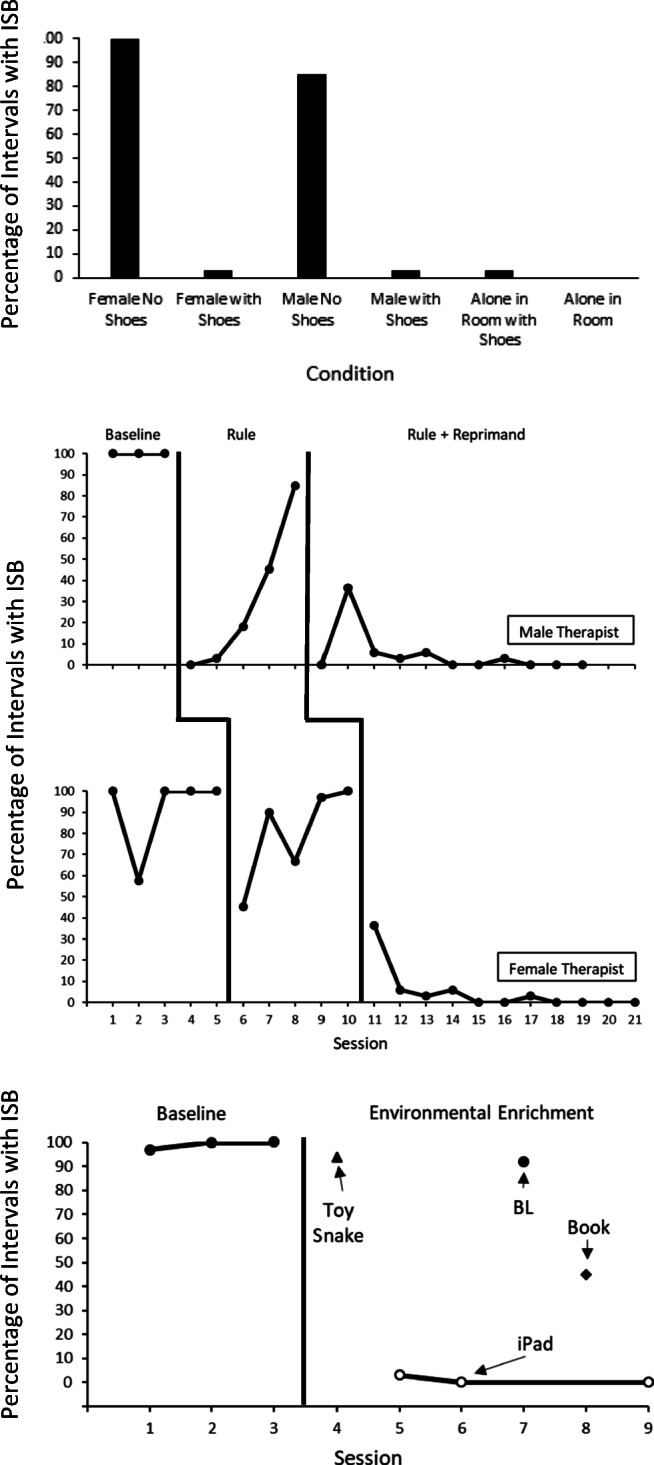

The top panel of Fig. 1 depicts the results of the functional analysis. Larry’s ISB occurred most often in the presence of the female with bare feet (M = 100%) and the male with bare feet (M = 85%). It occurred much less often in the presence of the female with shoes on (M = 3%), the male with shoes on (M = 3%), when Larry was alone in the presence of a pair of shoes (M = 3%), and when Larry was alone in the absence of shoes (M = 0%). Thus, these data suggest that ISB was evoked by the bare feet of individuals of either gender.

Fig. 1.

Results of the A-B functional analysis (top panel); results of the treatment evaluation, depicting inappropriate sexual behavior (ISB) during baseline (BL), rule, and rule plus reprimand conditions across therapists (middle panel); and results of the environmental enrichment treatment evaluation (bottom panel)

The middle panel of Fig. 1 depicts the results of the rule/reprimand treatment evaluation. During baseline with the male therapist (top panel of the treatment evaluation), ISB occurred for 100% of all intervals during each session. During the rule phase, Larry’s ISB initially occurred at low levels but steadily increased (M = 30%). Thus, we added the reprimand, which reduced ISB to low levels. ISB remained at low levels throughout this phase (M = 5%). During baseline with the female therapist (lower panel of the treatment evaluation), ISB was frequent (M = 92%). During the rule phase, Larry’s ISB decreased initially but then increased (M = 80%). During the reprimand phase, ISB decreased to low levels (M = 5%).

Data from the competing-stimulus assessment are not depicted in Fig. 1 but are described here. When the iPad was present, Larry interacted with it for a mean of 95% of intervals and exhibited ISB during a mean of 5% of intervals. When the book was present, Larry interacted with it during a mean of 7% of intervals and exhibited ISB during a mean of 93% of intervals. When the toy snake was present, Larry never interacted with it; he exhibited ISB during 100% of intervals.

The bottom panel of Fig. 1 depicts the results of the environmental enrichment treatment evaluation. During baseline, mean ISB was 99%. When the toy snake was present, Larry exhibited ISB during 94% of intervals. When the iPad was present, Larry exhibited ISB during a mean of 1% of intervals across sessions. During the baseline probe, ISB increased to 92%. When the book was present, ISB occurred during 45% of intervals.

The results of this study replicate the findings of Dozier et al. (2011) by illustrating the use of an A-B functional analysis to identify the specific features of feet that evoke ISB. Based on descriptive observations and parent report, Larry’s ISB was maintained by automatic reinforcement; it occurred in the absence of social consequences. Nevertheless, the A-B functional analysis was useful in that it enabled us to identify the specific features of feet (e.g., male vs. female, bare vs. shoes on) that evoked ISB. In this case, this was important, as it enabled us to identify situations in which extra vigilance and consistent use of an intervention may be required (e.g., at the pool, beach).

The results of this study extend Dozier et al. (2011) in that they provide an example of other interventions that may be used to decrease ISB evoked by a foot fetish. In contrast to the intervention identified as effective by Dozier et al. (2011)—response interruption / time-out—a rule/reprimand and environmental enrichment are relatively easy to deliver and may be more socially valid. Although the reprimand was punishment based, a function-based intervention would have likely been socially invalid or ineffective. Before they evaluated the response interruption / time-out, Dozier et al. (2011) evaluated a sensory-extinction procedure in which an athletic cup was placed over their participant’s genitals to decrease public masturbation. This intervention proved ineffective, perhaps because the participant increased the force with which he engaged in public masturbation. In our study, Larry’s mother did not approve of the use of an athletic cup.

It should be noted that masturbation when observing feet or other body parts may not be considered inappropriate when it occurs in private. Thus, other intervention components, such as providing access to pictures or videos of feet in private, may be an option for some individuals with foot fetishes. We suggested this as an intervention component, but Larry’s parents were concerned that allowing private masturbation in the presence of pictures or videos of feet would make public masturbation in the presence of feet more likely. We volunteered to teach Larry to discriminate between public and private contexts, but his parents declined. Of course, pictures or videos of feet may not have been stimulating to Larry. An intermediate step might have required us to transfer control over the response from actual feet to pictures or videos of feet.

To treat public masturbation, clinicians might also consider a multiple-schedule-based procedure, in which masturbation is permitted in the presence of a salient stimulus (e.g., a green card or wristband) but not in the presence of a different salient stimulus (e.g., a red card). Attempts to masturbate in the presence of the red card would be reprimanded or blocked. In contrast, clinicians might make the green card environment (e.g., a private room) conducive to healthy masturbation by providing access to erotic pictures, videos, or other stimuli. Masturbation is a healthy activity when done safely in a private setting (Levin, 2007); individuals with autism and related disabilities who choose to engage in this activity should be able to do so, just like the general population.

One limitation of this study is that we only used one male’s and one female’s feet in the functional analysis. Thus, it is possible that these specific feet, and not feet in general, evoked ISB. However, Larry’s parents reported that he had a history of ISB in the presence of a variety of people, so it is unlikely that the feet to which Larry was exposed in the functional analysis were the only feet that evoked his ISB. Another limitation is that we do not know if the reprimands by themselves (i.e., without a rule) would have been effective to decrease ISB.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Research Highlights

• According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), a fetishistic disorder is diagnosed when an individual experiences sexual urges focused on a nongenital body part or inanimate object and acts on those urges, which causes distress.

• Fetishistic behavior is often a harmless form of sexual activity, but it can be socially inappropriate, particularly when it occurs in public.

• In some cases, the specific stimuli that evoke inappropriate sexual behavior (ISB) can be identified via a functional analysis.

• Behavioral interventions including rules, reprimands, and environmental enrichment can be effective to reduce ISB.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

- Carr EG, Durand VM. Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18:111–126. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier CL, Iwata BA, Worsdell AS. Assessment and treatment of a foot-shoe fetish displayed by a man with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:133–137. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, Hagopian LP, Owens JC, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, DeLeon IG, Rodriguez-Catter V, Keeney KM. Enhancing the effects of extinction on attention-maintained behavior through noncontingent delivery of attention or stimuli identified via a competing stimulus assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:171–184. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin RJ. Sexual activity, health and well-being—the beneficial roles of coitus and masturbation. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2007;22(1):135–148. doi: 10.1080/14681990601149197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schöttle D, Briken P, Tüscher O, Turner D. Sexuality in autism: Hypersexual and paraphilic behavior in women and men with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2017;19(4):381–393. doi: 10.3390/jcm8040425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]