Abstract

Most abduction-prevention strategies focus on teaching children safe responses to lures from strangers; however, statistics suggest that the majority of nonfamily abductions are conducted by people who are, to some extent, familiar to the child. We evaluated the effects of a safe-word intervention to address this discrepancy and decrease the likelihood that a child will leave with a person not appointed by his or her parents, regardless of whether the person is familiar or unfamiliar to the child. Five children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, aged 4–9 years old, were taught a 4-part response to lures from familiar and unfamiliar adults using a behavioral skills training package with in situ training added as needed. All participants met initial mastery criteria, with 4 of the 5 children requiring the addition of in situ training, and all maintained mastery levels at a 2-month follow-up.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorders, Abduction prevention, Safe-word

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, an estimated 58,200 children are victims of nonfamily abductions each year. Nonfamily abductions are defined as an instance in which a child is taken by the use of physical force, threats, or lure by a nonfamily member such as a friend, acquaintance, or stranger for a period of longer than 1 hr. The majority of these abductions (58%) are conducted by someone familiar to the child, such as a friend or long-term acquaintance, a person of assumed authority, a neighbor, or a babysitter (Finkelhor, Hammer, & Sedlak, 2002). Furthermore, most abductions do not involve the use of force, or threats of force, with children often going willingly with the adult in response to attempts to befriend the child and the presentation of some type of lure (Finkelhor, Hotaling, & Asdigian, 1995; Poche, Brouwer, & Swearingen, 1981). Although it is true that the majority of children will not encounter an abduction situation, those who do so and survive may suffer serious adverse psychological effects (Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor, 1995).

Although some systems have been developed to assist in the recovery of abducted children (e.g., AMBER alert system), some research suggests that estimates of their success may be overestimated or biased and should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, data suggest these systems may be more successful with parental abductions, which are generally considered to be less dangerous situations for the child than nonfamily abductions, and more research in this area is required (Griffin, Miller, Hoppe, Rebideaux, & Hammack, 2007).

Several researchers have approached the issue of child safety by teaching abduction-prevention skills to children. A number of such studies have utilized behavioral skills training (BST), often combined with in situ training (IST), to teach children a three-component response—a verbal response (e.g., to say no or “I have to ask if it’s OK.”) if the perpetrator has asked the child to go with him or her, a motor response (e.g., to move away from the perpetrator toward a parent, trusted adult, or the child’s home or school location), and a reporting response (e.g., to tell a trusted adult)—and have assessed the effectiveness of such training using in situ probes (Johnson et al., 2005, 2006; Miltenberger et al., 2013; Vanselow & Hanley, 2014).

BST is a behavior-based training package with multiple components that incorporate instructions, modeling, role-play, and feedback. IST is often implemented following a failed probe in the natural environment (e.g., the park, grocery store, or front yard) and involves the appearance of a researcher to provide immediate feedback and correction in a manner similar to BST, although often shortened (e.g., Bergstrom, Najdowski, & Tarbox, 2014; Gunby, Carr, & LeBlanc, 2010; Gunby & Rapp, 2014). It is utilized to enhance the generalization of the skills from training simulations to real-life situations. Studies suggest that interventions combining BST with IST are most effective for teaching abduction-prevention safety skills, especially when IST is incorporated immediately following BST (Johnson et al., 2006).

Although effective, BST and IST can be time consuming and require some degree of training to implement effectively. Given this, researchers have examined the effectiveness of video-based interventions (Beck & Miltenberger, 2009; Miltenberger et al., 2013) and computer-based interventions (Vanselow & Hanley, 2014) in teaching abduction-prevention skills. Overall, results suggest that neither video-based interventions nor computer-based interventions alone are effective but that both require the addition of IST to demonstrate safe responding to abduction lures from a stranger. Furthermore, some studies have trained parents (Beck & Miltenberger, 2009; Gross, Miltenberger, Knudson, Bosch, & Brower-Breitwieser, 2007; Miltenberger et al., 2013) to implement IST, and despite some fidelity issues, parents were generally able to implement such procedures effectively.

In assessing the effectiveness of BST and IST, studies often conduct in situ probes in natural settings. These are used to evaluate the extent to which the trained skills are likely to generalize to a possible real-life situation (Miltenberger & Olsen, 1996). Potential perpetrators (confederates of the researchers) typically approach the individual and either remain in proximity (Miltenberger et al., 2013) or present some variation on common lure types such as a simple lure, involving a straightforward request for the child to go with the perpetrator; an authoritative lure, suggesting that the perpetrator was sent by the child’s parent, teacher, or other authority figure; an incentive lure, offering the child some preferred item or activity if he or she goes with the perpetrator; and an assistance lure, asking the child for help that involves going with the perpetrator (Johnson et al., 2005, 2006; Poche et al., 1981).

Although many of these studies have shown the effectiveness of BST and IST in teaching abduction prevention to typically developing children, only a handful have attempted to do so with individuals with developmental and intellectual disabilities, including autism spectrum disorder. This is despite some enduring evidence that individuals with such disabilities are more vulnerable to a variety of types of personal and property crimes (Wilson & Brewer, 1992; Wilson, 2016). Gunby et al. (2010) taught abduction-prevention skills to three children with autism using BST in a classroom setting, with assessment probes conducted in a variety of other settings. Participants were taught to respond correctly to all four common lures (simple, incentive, authority, and assistance) and used the same three-part response (say no, run away, and tell someone). IST was provided, as needed, to two of the three participants, contingent on a failed probe, and the abduction-prevention skills were mastered and maintained for all three participants at a 1-month follow-up.

Fisher, Burke, and Griffin (2013) extended the prior study by implementing a similar protocol with five young adults with mild intellectual disabilities. BST was also conducted in their classroom, but IST was conducted for all participants in a manner similar to BST (not contingent on a failed probe but as a planned component of the intervention) in a variety of community settings. Once participants had met the mastery criteria during IST, they were exposed to confederate probes in the natural environment, and all participants eventually met mastery criteria and maintained their performance at a 3-month follow-up.

Bergstrom et al. (2014) also utilized BST in the home with children with autism and found it to be effective for two of the male participants, with the third requiring additional incentives and IST components. These skills generalized to novel settings for all participants.

One dominant feature of the prior studies is that many of the in situ probes or assessments were conducted by someone unfamiliar to the participant, and the training focused on the identification of a stranger and not a familiar person. Although an awareness of the danger posed by strangers and the strategies to implement in such situations are undoubtedly useful, the data presented by Finkelhor et al. (2002) suggest that we must also address the role of familiar individuals in abduction prevention and intervention. Specifically, these authors state that we must recognize and address their findings that more than half of all nonfamily abductions involve a perpetrator who is an acquaintance of the victim.

One possible intervention that may address the risk of abduction by familiar people is the use of a safe word. A safe-word intervention involves a word that is not common in the child’s vocabulary but is shared by parents with people who are authorized to collect the child or ask the child to go with them. In addition to addressing the role of familiar people in abductions, a safe-word intervention may provide a clearer discrimination (people who know the safe word and people who do not) than stranger-danger interventions (strangers and nonstrangers) do, particularly for individuals on the autism spectrum, who may apply the discrimination in a literal manner. For example, a stranger may begin by introducing him- or herself to the child, blurring the definition of a stranger, and perhaps leading the child to believe that he or she presents no danger. Moreover, it may not always be socially appropriate for children to run away from a stranger who approaches them and says something innocuous. For example, a stranger may deliver a compliment, or say hello to a child, neither of which present any particular risk (assuming the interaction goes no further). A safe-word intervention may be a more appropriate way to teach children to avoid people who are trying to get them alone or remove them from their current environment.

The purpose of the present study was to address the limitation in the current literature on stranger danger by teaching a safe-word intervention for abduction prevention to children with autism spectrum disorder.

Method

Participants

Five individuals, four males and one female, between 4 and 9 years of age, participated in this study. They all had an independent diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder and were receiving behavior-analytic services, primarily in the area of social skills training. The parents of all participants expressed concern about safety, specifically their children’s willingness to go with a variety of familiar and unfamiliar adults. All procedures were reviewed by the local university’s institutional review board, parents signed an informed consent form, and participants gave verbal assent to a description of the study that was read aloud to them. All participants were assessed using the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP; Sundberg, 2008) to provide an overall measure of various skill domains, including speaker and listener behavior, play skills, social skills, and preacademic skills. The VB-MAPP assesses 170 skills up to those expected of a typical 4-year-old. Participant scores can be seen in Table 1, along with specific ages and preferred items. All participants had either passed all 170 items in the assessment or were close to doing so. Each participant was also assessed to ensure he or she could follow multistep instructions, complete a four-step response chain, and engage in generalized imitation. All participants communicated in full sentences and were familiar with BST from their regular social skills training groups. For safety reasons, one participant with a recent history of elopement was excluded from the study.

Table 1.

Participant age, VB-MAPP score, and five most highly preferred items

| Participants | Age | VB-MAPP scores | Preferred items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nick | 4 | 157 |

Robots Ice cream Dogs SpongeBob Soda |

| Schmidt | 9 | 170 |

Video games Spiderman Legos Spaceship Animals |

| Jessica | 5 | 167 |

Frozen characters Play dough Dress up Books Soda |

| Sam | 7 | 162 |

Video games Ice cream Dogs Trains Oreos |

| Winston | 5 | 155 |

Dogs Scooter Ice cream Lollipops Trains |

Setting

Sessions were conducted across a variety of settings for all participants. For three of the participants, BST was conducted in a small applied research room at a local university, and IST was conducted in a variety of public places around the university campus. For the remaining two participants, BST was conducted in their homes, and IST was conducted in various public locations near their homes. For all participants, probe sessions were conducted in a variety of community settings that they frequently visited with their parents and other family members (e.g., shopping mall, library, front yard, grocery store, school playground, park). For the probe sessions, no location was used more than once. Sessions were conducted throughout the week with BST and IST sessions ranging from 30 to 60 min in duration and probe sessions ranging from 1 to 5 min. Participants required between 13 and 16 sessions to complete the study (including all probes, BST, IST, and follow-up).

Instruments

A small handheld camera was used to record all sessions for data collection. For BST and IST sessions, this was set up on a tripod or held by another person. For all probes, this was concealed on the confederate (e.g., in an outside breast pocket or discretely in his or her hand as a cellular device). In addition, the confederate was fitted with an in-ear Bluetooth device to allow the experimenter to communicate with him or her discretely throughout the probe. Additional research assistants, placed around the community settings, carried two-way radios to allow them to communicate with each other and with the experimenter, as needed.

Several adult confederates were recruited to assist in the study, and no confederate was used more than once with any given participant. Confederates were recruited through the participants’ parents, behavior-analytic service providers, and the Psychology Department’s master’s degree program via an informational flyer and a description of their potential role in the study. This allowed for the inclusion of adult confederates who were familiar to the child (defined as those who had interacted with the child in the last 2 months, knew the child by name, and believed that the child would know them by name), including friends of parents, relatives, previous therapists, and other clinic staff, and adults who were unfamiliar to the child. Within both categories, some adults knew the safe word, and others did not. Each confederate was provided with a written script, and the procedure was vocally described to him or her. The confederates had the opportunity to ask questions about the procedure and were instructed not to make physical contact with the child at any time during the probe. In addition, each confederate wore an earpiece device that allowed the experimenter to communicate with him or her discreetly at all times. As the confederate approached the child, the experimenter reminded him or her of the procedure, the script, and the specific lure to be used, as well as the excuse to be used, should the child agree to go with them.

Dependent Variable, Data Collection, and Interobserver Agreement

The dependent variable across all training sessions was the participant’s response to the lures and nonexemplars (innocuous statements) presented, and the dependent variable on all probes was the participant’s response to all lures presented by a confederate. All lures were coded using a four-point system. Upon presentation of the lure, one point was awarded for each of the following behaviors: (a) asking for the safe word within 5 s of the lure, (b) providing an appropriate vocal response to the confederate’s knowledge of the safe word (i.e., say OK if the confederate knows the safe word, or say no if the confederate does not know the safe word), (c) providing an appropriate nonvocal response to the confederate’s knowledge of the safe word (either leave with a confederate who knows the safe word or run away from the confederate who does not know the safe word), and (d) and reporting the incident. Each presentation of a lure (during BST, IST, or follow-up probe) received a score from 0 to 4 based on how many of the aforementioned behaviors were observed. A score of 0 was recorded if the participant agreed to leave with the confederate upon presentation of the lure, and the probe was immediately terminated. Nonexemplars were only included during training, and one point was scored for a contextually appropriate response to the comment or question, and a score of 0 was given for any other response, including asking for the safe word (see Table 2 for a representative sample of lures, nonexemplars, and responses). The nonexemplars were included in the training to ensure that participants did not just learn to respond by asking for the safe word on every rehearsal.

Table 2.

Sample representative of lures (exemplars), nonexemplars, and a correct response (one when the confederate knows the safe word, and variations of responses that might be presented for a confederate who does not know the safe word)

| Type of Scenario Presented | Sample Statement Presented | Sample Correct Response |

|---|---|---|

| Simple Lure | “Come with me.” |

Child: “Do you know the safe word?” Confederate: “Skyscraper” (correct safe word) Child: “Okay” and goes with the adult. Tells parent or adult. |

| Incentive Lure | “I have a new video game. Come with me and I’ll show you.” |

Child: “Do you know the safe word?” Confederate: “No” Child: “No” and runs away. Tells parent or adult. |

| Assistance Lure | “I’ve lost my dog. Can you come and help me find her?” |

Child: “I can’t come if you don’t know the safe word.” Confederate: “Is it abracadabra?” Child: “No” and runs away to adult or parent and reports it. |

| Authoritative Lure | “Your mom said it was ok for you to come to my house.” |

Child: “Did mom tell you the safe word” Confederate: “She must have forgotten.” Child: “No” and runs to parent to tell them. |

| Non-example | “I like your hat.” | Child: “Thank you.” and keeps moving along. |

The mastery criterion for BST and IST was 100% correct (i.e., scores of 4 out of 4 on all eight lures and a correct response on both nonexemplars presented in the training session) across two consecutive sessions. Participants were considered to have passed posttraining probes if they scored 100% on three out of four probes.

Video and audio were recorded for 80% of all training sessions and 66% of all probe sessions to allow for the collection of interobserver agreement (IOA) data. All recordings were scored by an undergraduate student in psychology, trained to serve as an independent data collector, and data were compared using a point-by-point system. The agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements on the occurrence of each response by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying this by 100. Agreement across all training and probe sessions was 90% and 95%, respectively. Experimenters were trained to implement procedures at 100% accuracy and were provided with a checklist to review before the start of each training and probe session and to reference throughout training sessions (but not probes). Procedural integrity measures were collected by graduate and undergraduate students in psychology, using the same checklist, for 70% of all training sessions and 100% of probe sessions, and procedures were implemented with 100% and 98% fidelity for training and probe sessions, respectively.

Design

The effects of BST and IST were evaluated using a nonconcurrent multiple-baseline design across participants to teach the safe-word intervention and the effects of this on abduction-prevention skills. Three to five baseline sessions were conducted with each participant, followed by BST until participants met the mastery criterion of 100%, on responses to lures and nonexemplars across two consecutive sessions, and they were then exposed to post-BST probes. Participants were required to score 4 out of 4 points on three consecutive probes, given a total of four opportunities. If they scored less than 4 on more than one of the probes (meaning they missed one of the steps in the safe-word intervention), they began IST. If they obtained a score of 4 across three out of four post-IST probes, they moved on to follow-up probes, which were conducted 1 week, 1 month, and 2 months after completion of the final post-BST or post-IST probe. IST was reimplemented if participants did not obtain a score of 4 on any of the follow-up probes.

Procedure

Prior to the start of the baseline probes, an indirect preference assessment was conducted by asking parents of participants to provide a list of preferred items. These can be seen in Table 1. Some were incorporated into the relevant lures during probes, and some were used as reinforcers for appropriate session behaviors during BST and IST sessions.

Abduction probes

During all probe sessions (baseline, post-BST, post-IST, and follow-up), participants were brought to a location familiar to them, either in the local community or in their front yard, and were not informed that this was an assessment. Parents were instructed to respond as though it were a normal outing and at some point, when the child seemed occupied, to make an excuse and leave the immediate area (e.g., “You stay here and look at the toys, while I go get something else. I’ll be right back.”). Parents were then out of sight but remained within 15 m of their children and were cued by the experimenter to make themselves visible on the perimeter immediately after their children completed their response to the lure and had begun to move away from the confederate or the confederate left the immediate area. Two to four additional experimenters (unfamiliar to the participant so as not to arouse suspicion) were placed around the perimeter of the area for added safety.

During each probe, a confederate approached the child and delivered one of the four types of lures, selected at random for that probe. If the child agreed to go with the confederate at any point during the lure, the confederate made an excuse and promptly left the area (e.g., if the child agreed to go with the confederate after the presentation of an assistance lure to help find his dog, the confederate would respond by saying, “Oh, never mind. I see my dog over there! Thanks anyway!” and leave the area). This was the case for confederates who knew the safe word, as well as for those who did not. If the participants were asked for the safe word, confederates would either provide the safe word if they knew it, attempt to guess it, or say that they didn’t know it (semirandomly assigned with at least one probe where the confederate knew the safe word). The parent reappeared as soon as the child moved away from the confederate or when the confederate left the vicinity of the child, and made no reference to the incident. If the child reported the incident, the parent provided verbal praise for doing so and continued with the outing. If the child did not report the incident, the parent made no reference to it and continued with the outing. No location or confederate was used more than once for any participant across probes.

BST

Upon completion of all baseline probes, BST was implemented with all participants during individual sessions. Prior to the first session, the parent was asked to decide on a safe word that would not be commonly used in the child’s day-to-day life or be easy to guess. Parents attended the first BST sessions where they informed their children and the experimenters of the safe word they had selected. Parents were not present in subsequent training sessions. BST sessions began with instruction on what a safe word was and descriptions of various scenarios in which it would be used. The participant was asked to state the appropriate safety response pertaining to each scenario: (a) ask for the safe word, say no, move away, and report the lure to a parent or caregiver or (b) ask for the safe word, say OK, leave with the adult, and report the use of the safe word to his or her parent or caregiver. These instructions were taught across multiple exemplars, varying the type of lure and the adults depicted. The experimenters modeled three exemplars and one nonexemplar in a random order during each session. The nonexemplar consisted of a comment about an item or activity and did not involve asking the participant to leave with them. Rehearsal opportunities that followed involved 10 role-play scenarios (two of each of the four lures and two nonexemplars). The experimenters used picture stimuli (photos of known and unknown people) during the modeling and rehearsal portions of the intervention to simulate the presentation of the lures and nonexemplars by various known and unknown people. This was done by the experimenter holding one card close to his or her face and pretending to be that person during role-play rehearsals. Correct responses were reinforced with praise and high-fives throughout training, and corrective feedback provided a model of the correct answer and represented the same lure or nonexample. Following each session, participants had the opportunity to select a small toy to take home based on compliance and appropriate session behaviors (e.g., watching models provided and responding to questions). Participants were exposed to one session per day and continued until they met mastery criterion (100% correct on all rehearsals across two consecutive sessions) without prompts. The participants were informed that they could take a break during any portion of the interventions. Participants were then exposed to post-BST abduction probes, as described previously.

IST

If participants did not pass post-BST probes (i.e., they did not score 4 out of 4 on three consecutive probes), they began IST sessions. IST was conducted in a manner similar to Fisher et al. (2013), and as such, participants were aware that this was a training situation. All procedures were similar to those used in BST except for the setting; IST sessions were conducted in a variety of public places (either around the university campus or the participants’ homes). In addition, the instructions used were briefer than those initially provided in BST. We conducted IST in this manner to ensure that IST was only provided to participants who required it and also to ensure that the confederate probes provided the most stringent measure of generalization possible. IST continued until participants met the mastery criterion (100% correct across two consecutive sessions), and participants were then exposed to post-IST probes that were conducted in the same manner as all other abduction probes, as described previously.

Follow-up probes

After participants met performance criteria during either post-BST or post-IST probes, 1-week, 1-month, and 2-month follow-up probes were conducted for each participant. These followed the same procedures as the baseline, post-BST, and post-IST probes. If participants failed any of the posttraining probes, IST was implemented, or reimplemented, following the same procedures described previously. If participants failed any of the follow-up probes, IST was reimplemented until they demonstrated 100% correct responding on one post-IST probe, and then follow-up probes began again.

Social validity

At the conclusion of the study, the parents of all participants were given a social validity questionnaire to assess their views on the importance of abduction prevention, the methods used in the study, and their satisfaction with the outcomes. This was presented on a Likert scale with a rating of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with eight items on the questionnaire, making for a maximum score (strongly agree with all items) of 40. In addition, parents were provided with written instructions on signs of child distress and suggestions of how to respond to any signs of distress, should they occur. This was developed in collaboration with the university’s psychological services team at the student health center. Parents were also provided with the contact information of the first and second authors to report any concerns.

Results

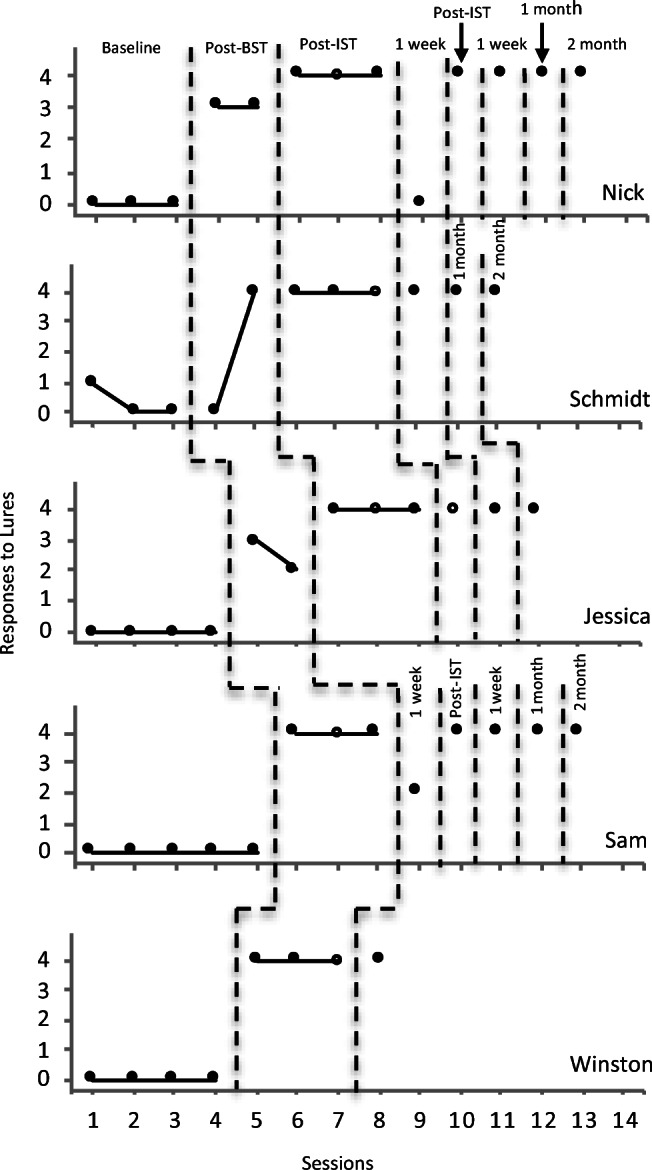

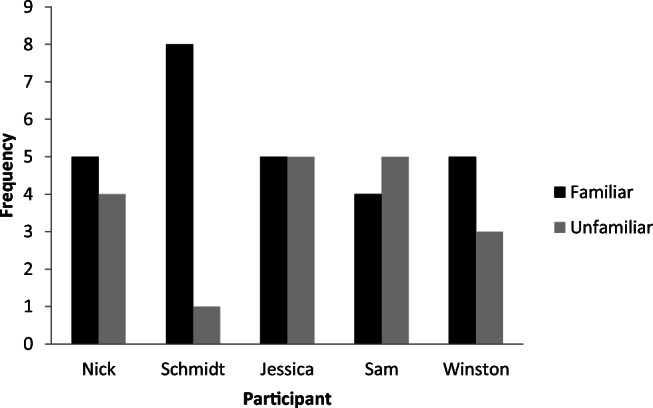

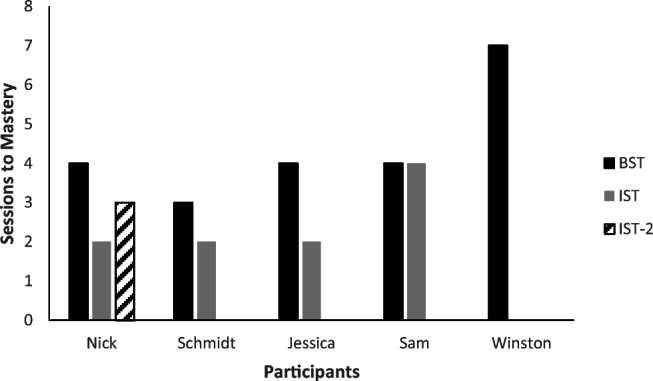

All five participants met the mastery criterion at posttraining and maintained accurate responding during follow-up probes. More specifically, three participants required both BST and IST to meet the mastery criterion in posttraining probes, one participant met the mastery criterion in posttraining probes with just BST but subsequently failed the 1-week follow-up probe and was exposed to IST before further posttraining and follow-up probes, and one participant met mastery and 1-week follow-up with BST alone but moved out of state and was unable to complete the additional follow-up probes at 1 and 2 months. Figure 1 depicts the performance of all five participants across baseline, posttraining, and follow-up probes. Figure 2 shows the distribution of familiar and unfamiliar adults for each participant, and Figure 3 shows the number of sessions required for each participant to meet the mastery criterion in each phase. Session-by-session training data are not presented but are available upon request.

Fig. 1.

Responses of all participants across baseline, post-BST (behavioral skills training), post-IST (in situ training), and follow-up probes. Open circles represent probes where the confederate knew the safe-word

Fig. 2.

Distribution of familiar and unfamiliar adult confederates

Fig. 3.

Number of sessions to mastery criterion across BST, IST, and repeated IST (IST-2)

Nick

During baseline, Nick scored 0 across all three probes and required four sessions of BST to meet the mastery criterion. During the post-BST probes, Nick failed to meet criterion twice, scoring 3 out of 4 on both probes by failing to ask for the safe word on one and failing to report the lure to his parents on the other. It should be noted that although he failed both of these probes, he did not agree to go with the confederate at any point. Nick subsequently met the mastery criterion again following two sessions of IST, scoring 4 across both sessions. He then maintained this performance across the post-IST probes, failed the 1-week follow-up probe involving a familiar adult, had one additional session of IST before meeting the criterion across post-IST probes, and maintained this at 1-week, 1-month, and 2-month follow-up probes. Nick’s probes involved five familiar and four unfamiliar confederates.

Schmidt

Schmidt scored 1 out of 4 on his first baseline probe as he refused to go with the unfamiliar adult. He received a score of 0 on the second and third probes with familiar adults. Schmidt met the mastery criterion after three sessions of BST but failed the post-BST probes, leaving with the familiar adult confederate. He then began IST and met the mastery criterion after two sessions, maintaining accurate responding at 1-week, 1-month, and 2-month follow-ups. Schmidt’s probes involved eight familiar and one unfamiliar adult confederate (see discussion).

Jessica

During baseline probes, Jessica obtained a score of 0 across all four probes. She met the mastery criterion after four sessions of BST and failed the first and second post-BST probes by failing to ask the adult confederate for the safe word on the first and failing to ask for the safe word and failing to report the lure to her parents during the second. It should be noted that although she failed both probes, she did not agree to leave with the confederate at any point during these probes. Jessica then received IST and scored 4 out of 4 on both sessions, entering into post-IST probes, where she maintained performance across three probes at 1-week, 1-month, and 2-month follow-ups. Jessica’s probes involved five familiar and four unfamiliar adults.

Sam

During baseline, Sam scored 0 out of 4 for all five probes. He met the mastery criterion after four sessions of BST and maintained this performance across post-BST but not at a 1-week follow-up. IST training was conducted, after which he met criteria for the post-IST probes at 1-week, 1-month, and 2-month follow-ups. Sam’s probes involved four familiar and five unfamiliar adult confederates.

Winston

During baseline probes, Winston scored 0 out of 4 across all four probes and required seven sessions of BST to meet the mastery criterion. This was noticeably more sessions than other participants; he frequently came close to meeting 100%, and when he did the first time, he then dropped below again, so it took him more training sessions to meet the criteria of two consecutive sessions at 100% correct responding during BST. He then scored 4 out of 4 on the subsequent post-BST probes, and his performance maintained at a 1-week follow-up. It may be that the greater number of sessions in BST reduced the need for IST, although we cannot be sure of this, as he was only assessed at a 1-week follow-up. Winston moved out of state before he could complete further follow-up probes. His probes involved five familiar and three unfamiliar adults.

Social Validity

The average social validity score across the parents of all participants was 36.4 out of 40, indicating that parents saw the issue of abduction prevention as very important, were happy with the methods used in this study, and thought this should be used with other children. The statement that was consistently rated lower involved parents’ belief that they could implement a similar intervention themselves. The average score for each statement can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Social validity questions and average parental scores

| Question | Average Rating and Range (1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree) |

|---|---|

| It is important for children to feel safe when out in their community. | 5 (5 to 5) |

| In general, children do not know enough about abduction prevention. | 3.8 (3 to 5) |

| My child enjoyed participating in the study. | 4.7 (4 to 5) |

| I observed positive increases in my child’s awareness of his/her surroundings. | 4.6 (4 to 5) |

| I believe the methods in this study may be used to encourage other families to use a safe-word intervention. | 5 (5 to 5) |

| I am happy my child was able to participate in this study. | 4.8 (4 to 5) |

| I would be willing to continue to practice the safe-word after this study. | 4.3 (4 to 5) |

| I believe that I could accurately implement this intervention on my own. | 2.3 (2 to 3) |

Discussion

Overall, results from this study support the findings from previous studies, showing that BST and IST are effective in teaching safety responses to children with autism (Bergstrom et al., 2014; Fisher et al., 2013; Gunby et al., 2010; Gunby & Rapp, 2014). All five participants achieved the mastery criterion with either BST or BST and IST, and all participants showed maintenance of skills and generalization across environments, adult confederates, and lure types. This study extended current research by addressing the issue of abduction by familiar adults and was the first, to our knowledge, to utilize a safe-word intervention.

The participants in this study did show mastery and maintenance of this safety response in relatively few sessions, and although duration data were not collected, the number of sessions is reported, and sessions ranged in duration from 30 to 60 min. Participants completed all BST and IST sessions that were required to pass posttraining probes in an average of seven sessions (with a range of five to nine). The number of each type of training session for each participant is displayed in Figure 3. Given this, the current procedure may be a viable method to address the role of familiar people or acquaintances in abductions, and variations may allow for more widespread and low-effort implementation of the safe-word procedure.

It should be noted that there was some variation across participants. In particular, Schmidt differed in that he only experienced an unfamiliar adult confederate once in the baseline probes, and confederates were familiar in all other probes. During postintervention probes, two unfamiliar adult confederates attempted to approach him to deliver the lure, but the probes were terminated as he quickly moved away from the unfamiliar confederate before the lure could be delivered. Parents reported that Schmidt had previously experienced a stranger-danger program, and this had heavily reinforced the behavior of walking or running away from any stranger. From this point on, only familiar adult confederates were used with Schmidt as he seemed to already have a repertoire for escaping and avoiding unfamiliar adults.

Sam was exceptional in his baseline probes in that he initiated a conversation with both familiar and unfamiliar adult confederates during two of his five probes. During two baseline probes, when Sam agreed to leave with the confederate, and the confederate made an excuse to terminate the trial, Sam provided specific information as to where the confederate could find him upon return and also took the confederate’s hand to lead the person to the room that the confederate was trying to locate.

Although the majority of participants failed at least one postintervention probe, only one participant agreed to leave with the confederate at any point after intervention training. The other four participants failed the probe for not asking for the safe word and/or not reporting the lure to their parents. Schmidt was the exception to this; he agreed to leave with a familiar adult who was a former instructor at his current social skills training program and whom Schmidt had a long history of rapport and compliance with. Future studies may consider teaching exceptions to these procedures for particular adults such as instructors or teachers, as children are frequently expected to comply with their instructions, at least within appropriate settings. It should also be noted that we did not collect demographic information on the confederates, and given the wide variety of individuals involved (university students, family friends, etc.), this may be important to ensure the generality of the findings and applicability to the broader literature.

Another limitation of the current study is that the confederates did not attempt to persuade the participant to tell them the safe word, nor did we assess the participants’ ability to keep a secret. Confederates did occasionally ask for the safe word or answer with an incorrect guess at the safe word. None of the participants responded by giving the confederate the safe word, although they may have done so if the confederate had persisted or asked in more subtle ways. Given that this would be a possible scenario in any real-life situation, future research should assess these skills and include various requests of the participant to tell the confederate the safe word throughout the training. This would ensure that the safe word is kept between parents and the child and is only shared by parents with relevant, trusted people.

A further limitation of the probe sessions is that they did not include nonexemplars. These were included in training to ensure that participants did not just learn to respond to the experimenters with a request for the safe word but made the appropriate discrimination based on the statement provided (i.e., the participant only asked for the safe word in response to a lure to go with the experimenter but did not ask for the safe word in response to any other comment or greeting). It may also have been beneficial to include the nonexemplars in probe sessions to ensure that participants responded similarly outside of training. In addition, it should be noted that only one probe was conducted with a confederate who knew the safe word, except for with Jessica, who received two of this type of probe. It may have been beneficial to include more of these types of probes to ensure accurate responding to confederates who knew the safe word across a variety of nontraining situations.

Although this study included four common types of lures (simple, authoritative, incentive, and assistance), it did not include the use of high-probability and low-probability request sequences, where the confederate asks the child other questions first before asking the child to leave the area. Gunby and Rapp (2014) demonstrated that the use of these types of request sequences was an effective way to deliver a lure. In the current study, nonexemplars (comments or questions that did not involve asking the child to leave the area) were included throughout training but not included in probes. Future research should include high-probability and low-probability request sequences to ensure that participants continue to engage in the trained response chain even with this type of lure presentation. Another method of presentation that was not examined in this study is the knock-on-the-door method described by Beck and Miltenberger (2009), and future studies may want to include this to ensure that training covers a wide range of nonforceful lure types.

It should also be noted that we did not directly assess participants for adverse reactions to the procedures used in the study. We did provide parents with information on possible signs of child distress and suggestions on how to respond, and parents, informally, reported that their children did not show any signs of distress or adverse reactions to the procedures at any time throughout the study or follow-up. In addition, parents responded favorably to the social validity statements about the procedures used and reported that they were happy with their children’s participation in the study. Despite this, future studies may want to explicitly ask parents or assess participants for any adverse reactions to the procedures.

Previous studies have also examined the inclusion of parents in the IST component of training and showed that all participants acquired the relevant abduction-prevention skills following parent-implemented IST (Miltenberger et al., 2013). Given the results of the social validity questionnaire, which indicated that parents were not confident that they could implement this procedure, it may also be helpful to examine methods and modifications that would allow parents to teach this intervention to their children.

Future studies may investigate the use of this procedure with various age groups, with and without autism. It may be particularly important to investigate the use of these procedures with younger children and to examine modifications that may be needed to simplify the safe-word intervention for younger children or those with more limited language abilities. It should be noted that Winston, one of the younger participants in the study, and also the participant with the lowest VB-MAPP score, required noticeably more sessions to meet the initial BST mastery criteria. A number of other studies have successfully used BST and IST to teach a variety of safety skills to preschool children (e.g., Johnson et al., 2005; Poche et al., 1981); however, there may be some complexities associated with this procedure (e.g., keeping the safe word a secret) that limit its use with younger children or those with more a limited understanding of the instructions. Future researchers should investigate the utility of this procedure for abduction prevention in children with autism who have more pronounced skill deficits and language impairments. Alternative methods may be needed to provide instruction in BST and to allow the participant to respond appropriately (i.e., to ask for the safe word, to respond with no or OK, and to report it to a parent or caregiver). Visual aids may be needed, and the methods to teach children to use these will likely be more intensive and may require more individualized prompting and reinforcement procedures.

Finally, the design of this study was a nonconcurrent multiple-baseline design across participants. This allowed for easier recruitment and implementation of the intervention with this population, especially given the parental concern and socially valid nature of the target behaviors. Having said that, a concurrent multiple-baseline design would have demonstrated stronger experimental control. The nonconcurrent design does not require that all participants be evaluated within the same period and can only control for maturation and exposure to the baseline procedures (Carr, 2005). Future studies may strengthen the demonstration of experimental control by using a concurrent multiple-baseline design.

Despite the widespread use of stranger-danger abduction-prevention programs and their clear utility in preventing abduction by strangers, we believe this study is an important addition to the abduction-prevention literature. It addresses the role of familiar people in nonfamily abductions and avoids any confusion or manipulation of the meaning of a stranger by a potential abductor. In addition, this approach may avoid negative reactions of the child to any known person in their environment. Future research may investigate the preferences of parents for such a procedure in comparison to a typical stranger-danger program. The widespread belief that strangers are the most common source of danger may result in a preference for a program that retains the well-known response to unknown people. Future research may also examine the combination of both procedures (move away from strangers and implement the safe-word procedure with any known person), as this would address the role of familiar people in abductions but also retain the well-known responses to strangers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Shayne Gazmin, Bhawandeep Bains, Rocio Nuñez, Alex Jones, Blain Hockridge, Geoff Browning, Michelle Avila, and Givan Bznuni for their assistance with this project.

This study is based on a thesis submitted by the first author, under the supervision of the second author, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the master of arts degree in psychology at California State University, Fresno.

Funding

This research was supported, in part, by a Faculty Sponsored Student Research Award from the College of Science and Mathematics at California State University, Fresno.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (California State University, Fresno, Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, protocol #774 ) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Research Highlights

• Safety skills, such as abduction prevention, are important skills to teach to children, including those with autism spectrum disorder.

• Previous studies have focused on stranger danger; however, data suggest that familiar people are often the perpetrators in child abductions.

• Behavioral skills training and in situ training were used to teach children with autism spectrum disorder a safe-word response to familiar and unfamiliar confederates.

• A four-part response was mastered and maintained for all participants.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Beck KV, Miltenberger RG. Evaluation of a commercially available program and in situ training by parents to teach abduction prevention skills to children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:761–772. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom R, Najdowski AC, Tarbox J. A systematic replication of teaching children with autism to respond appropriately to lures from strangers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47:861–865. doi: 10.1002/jaba.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boney-McCoy S, Finkelhor D. Psychosocial sequelae of violent victimization in a national youth sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:726–736. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.63.5.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JE. Recommendations for reporting multiple-baseline designs across participants. Behavioral Interventions. 2005;20:219–224. doi: 10.1002/bin.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor, D., Hammer, H., & Sedlak, A. J. (2002). Nonfamily abducted children: National estimates and characteristics. Retrieved from https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/library/publications/nonfamily-abducted-children-national-estimates-and-characteristics

- Finkelhor D, Hotaling G, Asdigian N. Attempted non-family abductions. Child Welfare. 1995;34:941–955. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher MH, Burke MM, Griffin MM. Teaching young adults with disabilities to respond appropriately to lures from strangers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:528–533. doi: 10.1002/jaba.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin T, Miller MK, Hoppe J, Rebideaux A, Hammack R. A preliminary examination of AMBER alert’s effects. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2007;18:378–394. doi: 10.1177/0887403407302332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, Miltenberger R, Knudson P, Bosch A, Brower-Breitwieser C. Preliminary evaluation of a parent training program to prevent gunplay. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:691–695. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.691-695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunby KV, Carr JE, LeBlanc LA. Teaching abduction prevention skills to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:107–112. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunby KV, Rapp JT. The use of behavioral skills training and in situ feedback to protect children with autism from abduction lures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47:856–860. doi: 10.1002/jaba.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BM, Miltenberger RG, Egemo-Helm K, Jostad CM, Flessner C, Gatheridge B. Evaluation of behavioral skills training for teaching abduction-prevention skills to young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:67–78. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.26-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BM, Miltenberger RG, Knudson P, Egemo-Helm K, Kelso P, Jostad C, Langley L. A preliminary evaluation of two behavioral skills training procedures for teaching abduction-prevention skills to schoolchildren. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:25–34. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.167-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger RG, Olsen LA. Abduction prevention training: A review of findings and issues for future children. Education and Treatment of Children. 1996;19:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger RG, Fogel VA, Beck KV, Koehler S, Shayne R, Noah J, et al. Efficacy of the stranger safety abduction-prevention program and parent conducted in situ training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:817–820. doi: 10.1002/jaba.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poche C, Brouwer R, Swearingen M. Teaching self-protection to young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14:169–176. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML. Verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program. Concord, CA: AVB Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vanselow NR, Hanley GP. An evaluation of computerized behavioral skills training to teach safety skills to young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47:1–19. doi: 10.1002/jaba.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C. Victimization and social vulnerability of adults with intellectual disability: Revisiting Wilson and Brewer (1992) and responding to updated research. Australian Psychologist. 2016;51:73–75. doi: 10.1111/ap.12202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C, Brewer N. The incidence of criminal victimization of individuals with an intellectual disability. Australian Psychologist. 1992;27:114–117. doi: 10.1080/00050069208257591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]