Abstract

Increasing diversity and inclusion among organizational membership has become a focus for many professional societies, including the Society for Epidemiologic Research (SER). In this issue of the Journal, DeVilbiss et al. (Am J Epidemiol. 2020:189(10):998–1010) assessed dimensions of diversity and inclusion within SER to provide baseline data for future evaluations of Society initiatives. In our response, we note that diversity in SER appears strong but there is lag with regard to inclusion. We also highlight some of the major weaknesses of this study that hinder efforts to accurately evaluate inclusion within SER. There is a need to more concretely define inclusion and think broadly about how measures of inclusion should be operationalized in future surveys. Additional limitations of the study include its limited generalizability to the wider SER membership and the lack of questions about barriers to inclusion in SER activities. We conclude with recommendations for SER and other professional societies based on prior literature evaluating successful diversity and inclusion efforts. We also propose a conceptual model to assist with operationalizing and directing future analyses of inclusion measures. It is essential that SER move beyond efforts around diversity to focus on measuring and enhancing inclusion.

Keywords: diversity, inclusion, professional organization, representation

Abbreviations

- SER

Society for Epidemiologic Research

Editor’s note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Memberships of professional associations and societies are becoming increasingly diverse. Effectively catering to and leveraging a diverse membership can lead to more robust and rigorous scientific research (1) and opportune innovations (2). Research on the diversification of associations, however, has primarily focused on defining diversity and inclusion (i.e., Diversity 1.0) (3, 4) and less frequently on identifying policies and strategies that successfully increase diversity as well as inclusion within organizations (i.e., Diversity 2.0) (5, 6). Following the first generation of research, DeVilbiss et al. (7) used various measures of diversity to characterize the membership within the Society for Epidemiology Research (SER). They also assessed perceived inclusion by asking members whether they felt welcomed within the association and what activities they had participated in. While this is an important step in understanding the diversity challenges within this organization, DeVilbiss et al. (7), raise a number of points related to issues of inclusion (e.g., disparities in engagement) that warrant additional consideration. In this commentary, we highlight the importance of diversity within SER and provide a series of recommendations regarding measures and practices for improving inclusion (including how to assess engagement) within professional organizations like SER.

MEASURES OF DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION

Diversity and inclusion are often treated as synonymous, but in reality they are distinct concepts that both contribute to the equity climate in an organization. Diversity is defined as having a range of faces in the organization—people from different demographic groups, such as race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, religion, and nationality (8). Increased diversity contributes to the knowledge base that an organization can rely on, or in the case of SER, the broad range of science, ideas, and cultural knowledge owned by its membership (1, 2). Organizations increasingly focus on boosting their diversity, to include new ideas and for ethical, legal, and public relations reasons.

In contrast, inclusion often gets left in the shadow of diversity. Inclusion is whether those who are in an organization experience acceptance of their identities and ideas, feel a part of the system in both formal and informal ways, and sense that their voices and opinions are welcomed at every level of decision making (9). A study of social workers in the United States reported that increased job satisfaction was closely linked to actionable efforts of inclusion in organizational processes, while racial composition of the organization did not predict job satisfaction (10). Thus, while intent to increase diversity is an important first step, efforts that promote inclusion are more impactful in retaining and engaging individuals.

We are encouraged that DeVilbiss et al. (7) operationalized diversity and inclusion separately. Their survey appropriately addressed several dimensions of diversity, including age, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, political affiliation, religion, immigrant origin, family structure, level of academic training, and household income. However, we are concerned that recruitment methods (such as mentioning diversity in the cover letter) might have resulted in oversampling from subgroups of SER members from underrepresented identities such that results cannot be generalized to the wider SER community. This is one of the limitations mentioned by the authors and can be seen in the underrepresentation of survey participants who reported society-initiated participation, suggesting a lack of survey participation from more senior members. In spite of this potential limitation, we believe that DeVilbiss et al. effectively showed various dimensions of diversity among SER members. In doing so, this work advances the mission of its Diversity and Inclusion Committee, which aims to diversify SER’s membership in terms of backgrounds and career stages.

However, we argue that conceptualization and operationalization of inclusion is a weakness in this survey. The authors’ conceptualization of what defines “inclusion” was not articulated throughout the article, and it was unclear whether a standard definition of inclusion was provided in the survey. Compared with the conceptualization of diversity, the concept of inclusion was minimally represented in the survey questions. In particular, we are unsure whether “feeling welcomed” and “participation,” as chosen by the authors, are sufficient measures of inclusion. These measures of participation do not capture different dimensions of influence, power, and leadership within SER. Members from diverse backgrounds might participate in multiple levels but might not feel able to fully contribute, or influence processes, or might feel tokenized or unwelcome, potentially contributing to disengagement and loss of long-term membership. Researchers and practitioners of diversity management have developed several measures of diversity and inclusion that would have given a more complete, yet still potentially limited, measure of inclusion (11, 12). Finally, the survey misses an important opportunity to measure perceived barriers (e.g., time, travel, cost, etc.) to participation in SER and also does not assess structural discrimination in the organization. These measures would provide clear targets for addressing issues of inclusion in the future.

Although many respondents felt that SER was a welcoming space, it might not be an equally inclusive space for everyone. This latter sentiment might be a function of SER operating on a “discrimination and fairness” paradigm, which Ely and Thomas (8) define as an organizational lens that emphasizes equal opportunity (no discrimination) and fair treatment for all diverse members. Organizations that operate within this paradigm are often concerned with assessing and increasing diversity recruitment goals (e.g., demographic compositions of their members) rather than the degree to which employees can leverage their personal assets and perspectives to do their work more effectively within their organizations (i.e., inclusion). Moving toward greater inclusion will require changing professional societies such as SER, not just focusing on making constituencies more diverse. Many organizations succeed at diversity initiatives but struggle with inclusion because the system cannot be inclusive without changing itself. Seeking greater diversity is only the first step—the next is to change the system to create a space where diverse groups feel supported, respected, welcomed, and willing to contribute.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SER AND OTHER PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

As organizations work toward increasing diversity and promoting inclusion, there is a growing body of literature on how best to accomplish this (13–15). A meta-analysis of diversity management studies suggested several steps to build a climate of inclusion. First, organizations should make concrete efforts to continuously assess diversity and recruit underrepresented members. Second, policies and procedures should be instituted to engage every member and promote a sense of being valued and welcomed. Third, organizations should regularly evaluate the climate of inclusion using previously used measures that capture members’ views on policies and practices of diversity and inclusion within the organization. Finally, the authors of the meta-analysis emphasize that organizations should apply inclusion practices at every level of the institution including leadership and management (9).

As mentioned above, many academic institutions and professional organizations focus their initial efforts on creating a diverse trainee population. In fact, this is likely reflected in the diverse group of respondents to the SER survey, most of whom had been part of SER for <10 years. However, recruiting this diverse trainee population is not enough to support and retain them. Access to effective mentorship is strongly linked to the success of underrepresented minority students (16). However, studies have shown that while there has been an increase in the diversity of trainees within academia, there is a pipeline effect that results in less diversity among faculty and senior level positions (17–20). This could mean that within academic and professional organizations, mentors might not be prepared to effectively mentor the diverse mentees that they are matched with. We applaud SER for recently beginning a pilot mentoring program within their organization that matches young investigator members with members in more senior-level positions. We strongly believe that this program could benefit early-stage investigators, although we hope that SER mentors and mentees are supported with resources for culturally competent mentoring such as those available through the National Research Mentoring Network (NRMN).

The authors of this commentary are trainees from diverse ethnic, racial, and income backgrounds, from a variety of disciplines, who approach cancer research utilizing different methodologies. These include common biostatistical and epidemiologic methods but also econometrics, qualitative interviews, focus groups, community-engaged and community-based participatory research (CBPR), and others. Not only have we failed to see ourselves reflected in senior levels of academic institutions and professional organizations, we have also failed to see the type of work we do reflected and supported within organizations like SER. While the variety of approaches and methods we use are taught broadly in public health education systems and training programs across the country, SER has not placed much emphasis on highlighting these diverse methodologies equally.

It is critical to institute concrete policies and procedures within organizations that give every member a sense that their voices and participation are valued at all levels of decision-making. One such example, already established at the annual SER meetings, is offering sessions that highlight diverse research topics (e.g., health disparities) and methodologies hosted by the chair(s) of the Diversity and Inclusion Committee. While this is to be commended, a larger repertoire of inclusion strategies must be assessed, employed, or made more transparent within SER.

CONCLUSION

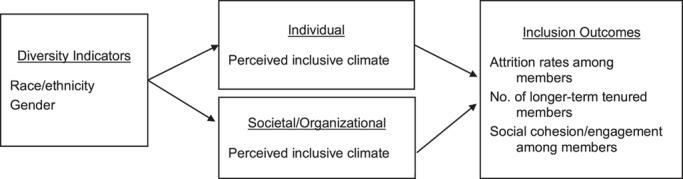

In order for SER to grow more inclusive, it is important to focus on improving the presence, power, and influence of diverse members. SER should engage and evaluate reported inclusion of diverse members in the planning and organization of the society, especially positions of power that determine the shape of SER and its content. We suggest that in addition to measuring the makeup of the SER membership, the Diversity and Inclusion Committee also make publicly available the makeup of its committees and leadership to determine whether the power of planning and shaping SER is shared, and create transparency in these outcomes. In addition, due to low response rates of those who indicated society-initiated event participation, we suggest that SER pull internal data of society-initiated events to determine the inclusivity of more prestigious and prominent participation. This might be a follow-up study or a report made available to society members. To that end, we suggest a conceptual model directing future analyses regarding measures of inclusion, including: 1) parsing out measures of inclusion by individual and societal/organizational levels to develop a more nuanced understanding of individual agency and organizational climate that facilitates or impedes inclusion within SER; and 2) increasing emphasis on measures of “societal/organizational” factors and “inclusion outcomes” (see Figure 1). Collecting measurements on inclusion outcomes, such as social cohesion/engagement among SER members, will help to codify endpoints that assess the impact of inclusive strategies employed within SER. Many validated scales assessing group social cohesion, which have also been used to predict retention, are widely available and can be modified for the context of SER (21–23). Furthermore, conducting a mediation analysis of which inclusion domains/mediators (e.g., individual, societal/organizational) have a greater influence on remaining engaged/included (e.g., retention) might help focus efforts on strategies and practices within SER to increase inclusion.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model directing future analyses regarding measures of inclusion, including: 1) parsing out measures of inclusion by individual and societal/organizational levels to develop a more nuanced understanding of individual agency and organizational climate that facilitates or impedes inclusion within the Society for Epidemiologic Research; and 2) increasing emphasis on measures of societal/organizational factors and inclusion outcomes.

We believe that continuing to measure diversity and inclusion in future surveys, as posited in the conceptual model, will contribute valuable information in assessing the longitudinal diversity and equity climate in SER. In future surveys, we also suggest efforts to boost response rates, especially from long-term members (≥10 years) and those with society-initiated participation. This might be achieved through a letter targeting all members, by providing a small incentive, or by using multiple modes (such as an in-person version of the survey administered at SER’s annual meeting). We also recommend hosting a panel to determine community response to DeVilbiss et al. (7). This panel could include the authors of the original paper, authors of invited commentaries, and others who are interested in expanding SER’s diversity and inclusion.

Finally, SER’s Diversity and Inclusion Committee should continue to use and share information gained from the survey (including the open-ended questions soliciting recommendations for improving diversity and inclusion within SER), additional membership analyses (including those described above), and commentaries and reactions to the results from DeVilbiss et al. as it moves forward with its mission. It is now incumbent on SER to follow suit with the second generation of research in diversity and inclusion, and move beyond just diversity to focus on measuring and improving inclusion among its members long-term.

Acknowledgments

Author affiliations: Program in Health Disparities Research, Department of Family Medicine & Community Health, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Kristin J. Moore, Gabriela Bustamante); Division of Epidemiology & Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Serena Xiong, Collin Calvert); and Department of Health Policy and Management, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Manami Bhattacharya).

K.J.M. and S.X. contributed equally to this work.

This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32CA163184 (PI: Michele Allen, MD, MS).

We sincerely thank Drs. Kathleen Call, Susan Everson-Rose, Michele Allen, and other faculty members on our T32 training program for their support and guidance in writing this commentary and in pursuing our individual research paths.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Campbell LG, Mehtani S, Dozier ME, et al. Gender-heterogeneous working groups produce higher quality science. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e79147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Østergaard CR, Timmermans B, Kristinsson K. Does a different view create something new? The effect of employee diversity on innovation. Res Policy. 2011;40(3):500–509. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pitts DW, Wise LR. Workforce diversity in the new millennium: prospects for research. Rev Public Pers Adm. 2010;30(1):44–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shore LM, Chung-Herrera BG, Dean MA, et al. Diversity in organizations: where are we now and where are we going? Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2009;19(2):117–133. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kulik CT. Working below and above the line: the research-practice gap in diversity management. Hum Resour Manag J. 2014;24(2):129–144. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mundy DE. Diversity 2.0: how the public relations function can take the lead in a new generation of diversity and inclusion (D&I) initiatives. Res J Inst Public Relations. 2015;2(2):1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7. DeVilbiss EA, Weuve J, Fink DS, et al. Assessing representation and perceived inclusion among members of the Society for Epidemiologic Research. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189(10):998–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ely RJ, Thomas DA. Cultural diversity at work: the effects of diversity on work group processes and outcomes. Adm Sci Q. 2001;46(2):229–273. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mor Barak ME, Lizano EL, Kim A, et al. The promise of diversity management for climate of inclusion: a state-of-the-art review and meta-analysis. Hum Serv Organ Manag Leadersh Gov. 2016;40(4):305–333. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Acquavita SP, Pittman J, Gibbons M, et al. Personal and organizational diversity factors’ impact on social workers’ job satisfaction: results from a national internet-based survey. Adm Soc Work. 2009;33(2):151–166. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mor Barak ME. Managing Diversity: Toward a Globally Inclusive Workplace. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nishii LH. The benefits of climate for inclusion for gender-diverse groups. Acad Manag J. 2013;50(6):1754–1774. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gonzaga AMR, Appiah-Pippim J, Onumah CM, et al. A framework for inclusive graduate medical education recruitment strategies. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):710–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferdman BM. The practice of inclusion in diverse organizations In: Ferdman BM, Deane BR, eds. Diversity at Work: The Practice of Inclusion. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2014:3–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development and Office of the Under Secretary Advancing diversity and inclusion in higher education. . https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/research/pubs/advancing-diversity-inclusion.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2020.

- 16. Martinez LR, Boucaud DW, Casadevall A, et al. Factors contributing to the success of NIH-designated underrepresented minorities in academic and nonacademic research positions. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2018;17(2):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoppe TA, Litovitz A, Willis KA, et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/Black scientists. Sci Adv. 2019;5(10):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aldrich MC, Cust AE, Raynes-Greenow C. Gender equity in epidemiology: a policy brief. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;35(2019):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krupnick M. Divided we learn: After colleges promised to increase it, hiring of Black faculty declined. https://hechingerreport.org/after-colleges-promised-to-increase-it-hiring-of-black-faculty-declined/. Accessed March 8, 2020.

- 20. Dutt-Ballerstadt R. In our own words: institutional betrayals. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/03/06/underrepresented-faculty-members-share-real-reasons-they-have-left-various. Accessed March 8, 2020.

- 21. Hansen MH, Morrow JL, Batista JC. The impact of trust on cooperative membership retention, performance, and satisfaction: an exploratory study. Int Food Agribus Manag Rev. 2002;5(1):41–59. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rice S, Fallon B. Retention of volunteers in the emergency services: exploring interpersonal and group cohesion factors. Aust J Emerg Manag. 2011;26(1):18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Treadwell T, Lavertue N, Kumar V, et al. The group cohesion scale-revised: reliability and validity. Int J Action Methods. 2001;54(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]