Abstract

In the 1930s, maps created by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) nationalized residential racial segregation via “redlining,” whereby HOLC designated and colored in red areas they deemed to be unsuitable for mortgage lending on account of their Black, foreign-born, or low-income residents. We used the recently digitized HOLC redlining maps for 28 municipalities in Massachusetts to analyze Massachusetts Cancer Registry data for late stage at diagnosis for cervical, breast, lung, and colorectal cancer (2001–2015). Multivariable analyses indicated that, net of age, sex/gender, and race/ethnicity, residing in a previously HOLC-redlined area imposed an elevated risk for late stage at diagnosis, even for residents of census tracts with present-day economic and racial privilege, whereas the best historical HOLC grade was not protective for residents of census tracts without such current privilege. For example, a substantially elevated risk of late stage at diagnosis occurred among men with lung cancer residing in currently privileged areas that had been redlined (risk ratio = 1.17, 95% confidence interval: 1.06, 1.29), whereas such risk was attenuated among men residing in census tracts lacking such current privilege (risk ratio = 1.01, 95% confidence interval: 0.94, 1.08). Research on historical redlining as a structural driver of health inequities is warranted.

Keywords: breast cancer, cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, health inequities, historical redlining, lung cancer, residential segregation, stage at diagnosis

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- CT

census tract

- HOLC

Home Owners' Loan Corporation

- ICE

Index of Concentration at the Extremes

- MCR

Massachusetts Cancer Registry

- RR

risk ratio

Surprisingly little research has empirically investigated the contemporary health implications of historical US governmental policies that have structured contemporary residential segregation, including the practice of “redlining” (1–4). The term “redlining” arises from maps produced by the federally sponsored Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) in the 1930s (1, 3), which have only recently been digitized (3). The HOLC maps employed a 4-color schema to designate an area’s merit ranking for mortgages (A/“best” = green, B/“still desirable” = blue, C/“definitely declining” = yellow, and D/“hazardous” = red), with neighborhoods whose residents were Black, disproportionately low-income or foreign-born, or racially integrated being assigned to the last category (see Web Table 1, available at https://academic.oup.com/aje, for examples of the HOLC appraisals). Banks deemed redlined areas risky for business, leading to the denial of mortgages and disinvestment in neighborhoods, with an explicit objective of keeping specific neighborhoods White and constraining where populations of color could live (1–4). Documented sequelae of the 1930s policy of redlining include contemporary residential segregation and its many corollaries: racial/ethnic inequities in home ownership, wealth, education, employment, transportation, and environmental pollution (1–5). Adverse health impacts of contemporary racial segregation across the life course, from infancy to death, are well documented (6–8).

Scant research, however, has examined whether historical redlining continues to structure current health inequities—that is, social group differences in health that are unfair, avoidable, and preventable (7, 9, 10). Not merely of historical interest, such questions are highly relevant to current policy debates about potential remedies (1, 2, 11, 12). To date, 4 published studies, each focused on single cities, have documented associations between historical redlining and health outcomes: tuberculosis incidence in 1951 in Austin, Texas (13); firearm injury rates in 2013–2014 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (14); self-rated health in 2008–2013 in Detroit, Michigan (15); and alcohol outlet clusters in 2016 in Baltimore, Maryland (16), in addition to 2 conference abstracts pertaining to asthma (17, 18).

To build the evidence base, we conducted a multicity analysis of historical redlining and current health inequities involving the 28 municipalities in Massachusetts with digitized redlining maps (1937–1938; Web Appendix and Web Figure 1). Our health outcome comprised 2001–2015 Massachusetts Cancer Registry (MCR) data for stage at diagnosis for primary invasive cervical, breast, lung, and colorectal cancer, with analyses taking into account contemporary neighborhood conditions, based on the cases’ residential census tract (CT) at the time of diagnosis.

We examined cancer registry data for primary invasive cancers’ stage at diagnosis because: 1) well-known racial/ethnic, economic, and geographic inequities exist for late stage at diagnosis (19, 20); 2) although cancers may have long etiological periods, current neighborhood factors, including inability to access health care and inadequate transportation, can affect stage at diagnosis and biological embodiment of risk (19, 20); and 3) cancer registries’ rigorous protocols minimize selection bias via utilizing comprehensive catchment area data on screening, receipt of medical care, and death certificates (with registry certification requiring less than 1.5% cases first reported solely at death) (21, 22). Data on stage distribution are key for cancer surveillance (23), with stage at diagnosis being highly predictive of patient survival (23–26). Guiding our choice of the 4 selected cancer sites were 2 considerations: 1) breast, lung, and colorectal cancer were leading causes of cancer morbidity and mortality in both Massachusetts and the United States (24–26) and 2) within Massachusetts, breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer were the focus of active screening programs intended to reduce health inequities in stage at diagnosis (25, 27).

METHODS

Study population

We obtained cancer data from the MCR (24) for all cases of primary invasive cancer (n = 53,196) diagnosed between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2015, for 4 cancer sites—breast (women only; n = 20,808), cervix (n = 874), colorectum (n = 12,977), and lung (n = 18,537)—among persons who, at the time of diagnosis, lived in one of the 28 Massachusetts municipalities with digitized HOLC maps. Diagnostic codes are provided in Web Table 2. This study was approved as exempt by the institutional review boards of the MCR, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

MCR data

We obtained individual-level MCR data on the cancer patients’ age at diagnosis, sex/gender, and race/ethnicity (see categories in Web Table 2), as well as their residential address at the time of diagnosis. We categorized stage at diagnosis as early (local) versus late (regional or distant).

Geocoding of cases

At the MCR, one of the authors (P.D.W.) geocoded each patient’s residential address at diagnosis using ArcGIS (version 10.4.1) (28), following the rigorous protocols of the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project (29, 30). Per our data-use agreement with the MCR, we appended solely the 2010 CT and city/town geocodes to our analytical file, and we used the CT location to link the HOLC grade.

HOLC measures

We assigned a HOLC grade (A, B, C, D, “mixed,” or “no grade assigned”) to the 474 CTs in the 28 Massachusetts municipalities with HOLC maps (3), based on the percentage of the CTs’ land area included in any 1937–1938 HOLC area (see the Web Appendix for the methods employed, and, for illustration, see the 1938 HOLC map for Boston with 2010 CT boundaries superimposed in Web Figure 2). We assigned a HOLC grade of A–D for 297 (62.7%) CTs, 78 of which had 100% of their land area contained entirely within 1 larger HOLC area. For the 219 CTs with boundaries that crossed HOLC areas, we assigned the HOLC grade comprising ≥50% but <100% of their land area (average percentage of land area in the assigned HOLC grade = 74.4%). We categorized as “mixed” the 39 CTs for which ≥50% of their land was in areas with HOLC grades, with no HOLC grade accounting for ≥50% of the total land area. The remaining 138 CTs, with <50% of their land in HOLC areas, we categorized as “no grade assigned.” Because only 5 CTs were categorized as grade A/“green,” we combined the 2 grades deemed most credit-worthy, A and B (“green + blue”; n = 43 CTs), to serve as the analytical referent group.

Additional CT characteristics

To assess CT characteristics for the 2001–2015 study period (using 2010 normalized boundaries), we used 2000 US decennial census data (31) and the American Community Survey annual 5-year estimates for 2008–2015, using the 2006–2010, 2007–2011, 2008–2012, 2009–2013, 2010–2014, 2011–2015, 2012–2016, and 2013–2017 data sets (32), and interpolated values for the years 2001 through 2007. We conducted all analyses using census data with SAS, version 9.4 (33). We quantified the percentage of persons below the US federal poverty line and generated 5 measures of social spatial polarization, computed using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE), which ranges from −1 to 1 and quantifies the percentage of persons in an area living at either end of designated extremes of distributions (34–36); the relevant formulae and census variables are provided in Web Tables 2–4. The extreme groups for privilege versus deprivation, which we have employed in prior studies for diverse cancer and other health outcomes (35, 36), were: 1) for income polarization, high-income households versus low-income households (the top 20% and bottom 20% of US household incomes, respectively); 2) for racial privilege, persons categorized as non-Hispanic White versus non-Hispanic Black; and 3) for racialized economic segregation, persons in non-Hispanic White high-income households versus non-Hispanic Black low-income households. We also newly computed an ICE for housing tenure, setting the extremes as homeowners versus renters.

Statistical analyses

We used R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), version 3.5.3 (37), to conduct the statistical analyses, with all tests for statistical significance being 2-sided. We descriptively quantified the distribution of the individual-level cancer case data and CT-level variables and examined bivariate associations for all variables within and across levels. Given the high collinearity among the ICE and poverty measures (Web Table 5), as expected, we included these variables in separate regression models. Since results from models with natural cubic splines indicated the presence of nonlinear, nonmonotonic associations between our continuous predictor variables and the risk ratios for late stage at diagnosis, we employed categorical variables: 1) terciles for the ICE measures (based on the overall distribution for each ICE measure for the Massachusetts population) and 2) established poverty cutpoints (<5%, 5%–9.9%, 10%–19.9%, and ≥20%) (29, 30, 38). We also created combined variables to capture interactions between HOLC grade and the current CT metrics, with the referent category set as HOLC “green + blue” by either the CT top ICE tercile or CT low poverty (<5%).

We employed Poisson regression allowing for overdispersion, using the glm( ) function to model the age-standardized risk ratio for late stage at diagnosis versus early stage at diagnosis for each cancer outcome. For these models, we aggregated the data for each calendar year (2001–2015) into strata by cases’ CT of residence at the time of diagnosis, race/ethnicity, and sex/gender and utilized indirect age standardization to compute the number of expected cases in each stratum. We rejected a multilevel approach with random CT-level effects after fitting such models and finding that estimates of the CT-level variance were close to zero. For all analyses, we used cases with complete data because no variable had more than 0.8% missing data. Because of small numbers, we were unable to include in our analytical models separate strata for American Indians/Alaska Natives and the diverse groups classified by the US Census as “other, non-Hispanic”; however, we provide descriptive data for these groups in Web Table 2. We additionally report data for lung and colorectal cancer for women and men, both combined and by sex/gender, to ensure transparency of results relevant to understanding similarities as well as differences between these groups (39).

To inform building our multivariable models, we first conducted univariable analyses for associations, for each cancer site, between stage of diagnosis and the HOLC and current CT characteristics (Web Table 6). On the basis of these results, we used solely the ICE for racialized economic segregation in multivariable models, since this metric consistently displayed the steepest gradient across cancer sites. The age-standardized multivariable models controlled for race/ethnicity and sex/gender (unless sex/gender-stratified) and, separately, each of the CT characteristics. We first estimated adjusted associations for HOLC categories, interpretable as total effects of HOLC, and then considered models with interactions between CT HOLC and the ICE or poverty variables; we interpreted associations only for areas with HOLC grades of A + B, C, and D, but we included ungraded and mixed-grade areas in our analyses to retain complete coverage of the 28 municipalities. We also fitted the same models parameterized with main effects and interactions of HOLC and CT ICE or poverty in order to characterize controlled direct effects—that is, mediator-stratum-specific associations for HOLC grades.

To assemble evidence regarding the mediation of historical redlining effects by contemporary CT characteristics, we examined differences in the distribution of these CT characteristics across categories of HOLC, and we report both controlled direct effects and estimates of the residual disparity under hypothetical randomized interventions (40, 41) which set the mediator distributions to what were observed for a HOLC grade of A + B (green + blue). We implemented the nonparametric simulation-based approach of Imai et al. (41) and report the residual disparity and bootstrapped 95% confidence limits on the risk ratio scale. In this causal mediation framework, the residual disparity is identified under the assumptions of no unmeasured mediator-outcome confounding and no mediator-outcome confounder that is caused by the exposure (40, 41).

RESULTS

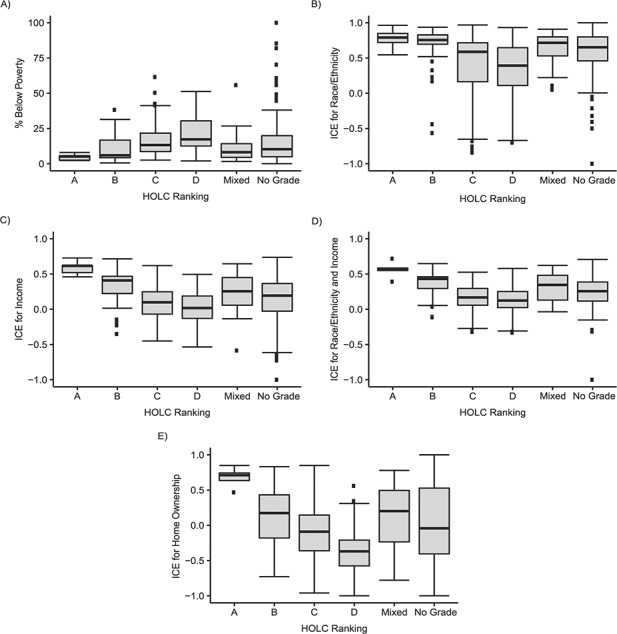

The 28 municipalities in Massachusetts with digitized HOLC maps contained 44.4% of Massachusetts’ total population in 1940 and 29.6% in 2001–2015 and were clustered around the Greater Boston area (Web Figure 3; Web Table 4). In 2001–2015, the 474 CTs in these 28 municipalities comprised 32% of Massachusetts’ 1,478 CTs, and their CT characteristics for the ICE and poverty measures exhibited a HOLC gradient (best for “A/green,” worst for “D/red”), with the mixed and ungraded CTs in the middle range (Figure 1; Web Table 4). These CTs also had more adverse contemporary ICE and poverty characteristics than the Massachusetts CTs in areas without HOLC maps (Figure 1; Web Table 4).

Figure 1.

Boxplots of current characteristics (2001–2015) of census tracts in 28 Massachusetts municipalities with Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps, by HOLC grade in 1937–1938. A) Percentage of persons living below the federal poverty level. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) F statistic (AFS): for all 6 HOLC categories (AFSall), AFS = 1.31 (P = 0.253); for HOLC categories A–D only (AFSA–D), AFS = 39.48 (P < 0.001). B) Index of concentration at the extremes (ICE) for race/ethnicity. AFSall = 4.76 (P = 0.030); AFSA–D = 14.39 (P < 0.001). C) ICE for income. AFSall = 0.25 (P = 0.614); AFSA–D = 55.13 (P < 0.001). D) ICE for race/ethnicity and income. AFSall = 0.59 (P = 0.442); AFSA–D = 45.46 (P < 0.001). E) ICE for home ownership. AFSall = 0.83 (P = 0.362); AFSA–D = 73.30 (P < 0.001). All tests of statistical significance were 2-sided. Operational definition of HOLC categories (x-axis): A, census tracts whose land area is (100% A or (≥50% A and <100% A)); B, census tracts whose land area is (100% B or (≥50% B and <100% B)); C, census tracts whose land area is (100% C or (≥50% C and <100% C)); D, census tracts whose land area is (100% D or (≥50% D and <100% D)); “mixed,” mixed census tracts with ≥50% of land area assigned HOLC grades but with no HOLC grade accounting for ≥50% of the total land area; “no grade assigned,” census tracts whose land area is ≥50% unknown.

With regard to the sociodemographic characteristics of the cases (details in Web Table 2), the average age of the cases at diagnosis ranged from 51.5 years for cervical cancer to 69.2 years for lung cancer. The proportion of cases categorized as persons of color was highest for cervical cancer (42.9%); non-Hispanic Whites comprised over 80% of cases for the other types of cancer. The proportions of cases that were late-stage at diagnosis (regional + distant) equaled 30.3% for breast cancer, 48.1% for cervical cancer, 56.4% for colorectal cancer (women: 57.8%; men: 55.1%), and 74.7% for lung cancer (women: 72.0%; men: 77.5%). Additionally, cervical and breast cancer cases had the most uneven distributions across categories of HOLC and CT characteristics: Cervical cancer cases were most likely (15.9%) and breast cancer cases least likely (11.2%) to live in historically redlined areas, whereas breast cancer cases were the most likely

(11.3%) and cervical cancer cases least likely (7.5%) to live in areas historically deemed credit-worthy (green + blue). Marked differences in CT ICE and poverty distributions by HOLC category occurred among the cancer cases (Web Figure 4). Univariable analyses for cancer stage at diagnosis in relation to HOLC category and current CT characteristics are provided in Web Table 6.

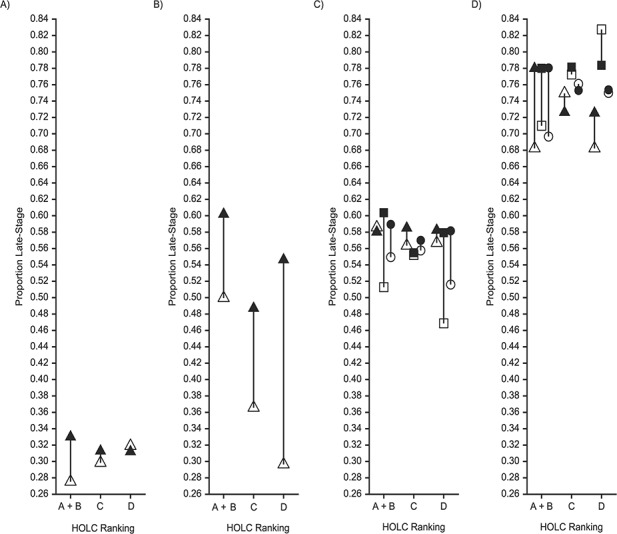

Models for the total effect of HOLC grade, adjusted for race/ethnicity and sex/gender (where appropriate), showed a pattern of increased risk of late-stage diagnosis in redlined and yellow areas for women with breast cancer (risk ratio (RR)red = 1.07, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.98, 1.17; RRyellow = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.99, 1.15) and men with lung cancer (RRred = 1.07, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.13; RRyellow = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.11) (Tables 1 and 2). Similar patterns were seen for total lung cancer cases. Controlled direct effects from multivariable models including HOLC × ICE interactions show that within ICE category T1 (tercile 1), HOLC disparities were generally larger than the total HOLC effects, with substantially elevated risk of late-stage diagnosis seen for women with breast cancer in redlined and yellow areas (RRred = 1.15, 95% CI: 0.95, 1.39; RRyellow = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.97, 1.22) and men with lung cancer (RRred = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.29; RRyellow = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.17), with similar patterns for total lung cancer cases. Correspondingly, HOLC disparities within ICE category T2 + T3 (terciles 2 and 3) were attenuated or even reversed relative to the total effects, though we note that baseline risks of late-stage diagnosis were substantially higher in green + blue areas in ICE category T2 + T3 (i.e., previously credit-worthy areas that now had higher extreme levels of low-income non-Hispanic Black households) relative to ICE category T1 (see Tables 1 and 2 and Web Table 6). Figure 2 displays the ICE inequities, by HOLC group, for the proportion of late-stage tumors.

Table 1.

Total Effect and Controlled Direct Effect of Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Ranking on Lung and Colorectal Cancer Stage at Diagnosis and Residual Disparity, Using Census Tract Index of Concentration at the Extremes for Racialized Economic Segregation as a Mediator, Massachusetts, 2001–2015a

| Lung Cancer | Colorectal Cancer | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Women | Men | Total | Women | Men | |||||||

| Comparison | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI |

| Total Effect b | ||||||||||||

| HOLC ranking | ||||||||||||

| Green + blue (best; referent) | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yellow | 1.04 | 1.00, 1.07 | 1.02 | 0.97, 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.01, 1.11 | 1.01 | 0.96, 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.93, 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.95, 1.11 |

| Red | 1.03 | 1.00, 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.95, 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.02, 1.13 | 1.02 | 0.96, 1.09 | 0.99 | 0.91, 1.09 | 1.05 | 0.96, 1.16 |

| Mixed HOLC grades | 1.02 | 0.98, 1.06 | 1.01 | 0.96, 1.07 | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.09 | 0.97 | 0.91, 1.04 | 1.00 | 0.91, 1.10 | 0.94 | 0.85, 1.04 |

| No grade assigned | 1.02 | 0.98, 1.05 | 0.99 | 0.94, 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.00, 1.10 | 1.00 | 0.95, 1.06 | 0.98 | 0.91, 1.06 | 1.02 | 0.94, 1.11 |

| Controlled Direct Effect c | ||||||||||||

| HOLC ranking by CT ICE tercile | ||||||||||||

| ICE tercile 1 | ||||||||||||

| Green + blue | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yellow | 1.09 | 1.03, 1.15 | 1.10 | 1.01, 1.18 | 1.09 | 1.01, 1.17 | 1.02 | 0.93, 1.12 | 0.96 | 0.85, 1.09 | 1.08 | 0.94, 1.24 |

| Red | 1.08 | 1.00, 1.16 | 1.00 | 0.89, 1.12 | 1.17 | 1.06, 1.29 | 0.95 | 0.82, 1.11 | 0.97 | 0.79, 1.20 | 0.92 | 0.74, 1.15 |

| Mixed | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.09 | 1.02 | 0.94, 1.11 | 1.04 | 0.96, 1.13 | 0.99 | 0.91, 1.09 | 0.95 | 0.84, 1.08 | 1.04 | 0.90, 1.19 |

| No grade | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.09 | 1.02 | 0.95, 1.09 | 1.06 | 0.99, 1.13 | 1.03 | 0.96, 1.11 | 0.95 | 0.85, 1.05 | 1.12 | 1.00, 1.26 |

| ICE terciles 2 and 3 | ||||||||||||

| Green + blued | 1.12 | 1.05, 1.19 | 1.14 | 1.04, 1.24 | 1.10 | 1.01, 1.19 | 1.08 | 0.97, 1.19 | 0.99 | 0.86, 1.13 | 1.19 | 1.02, 1.38 |

| Green + blue | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yellowe | 0.97 | 0.92, 1.02 | 0.94 | 0.87, 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.94, 1.07 | 0.97 | 0.89, 1.05 | 1.01 | 0.90, 1.14 | 0.92 | 0.81, 1.04 |

| Rede | 0.97 | 0.92, 1.02 | 0.94 | 0.87, 1.01 | 1.01 | 0.94, 1.08 | 0.99 | 0.90, 1.08 | 1.00 | 0.89, 1.14 | 0.96 | 0.84, 1.10 |

| Mixede | 0.98 | 0.92, 1.04 | 0.97 | 0.89, 1.05 | 1.00 | 0.92, 1.08 | 0.94 | 0.84, 1.04 | 1.05 | 0.91, 1.21 | 0.82 | 0.70, 0.96 |

| No gradee | 0.97 | 0.92, 1.02 | 0.93 | 0.86, 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.94, 1.08 | 0.95 | 0.87, 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.89, 1.13 | 0.89 | 0.78, 1.02 |

| Residual Disparity f | ||||||||||||

| HOLC ranking | ||||||||||||

| Green + blue (best; referent) | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yellow | 1.04 | 1.00, 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.00, 1.11 | 1.00 | 0.94, 1.06 | 0.98 | 0.91, 1.07 | 1.01 | 0.91, 1.12 |

| Red | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.08 | 0.97 | 0.90, 1.05 | 1.10 | 1.03, 1.17 | 0.96 | 0.87, 1.06 | 0.99 | 0.84, 1.14 | 0.94 | 0.80, 1.08 |

| Mixed HOLC grades | 1.01 | 0.97, 1.05 | 1.00 | 0.94, 1.06 | 1.02 | 0.96, 1.10 | 0.97 | 0.90, 1.04 | 0.99 | 0.90, 1.09 | 0.95 | 0.84, 1.06 |

| No grade assigned | 1.01 | 0.98, 1.04 | 0.98 | 0.93, 1.03 | 1.04 | 0.98, 1.09 | 1.00 | 0.94, 1.06 | 0.97 | 0.90, 1.05 | 1.03 | 0.94, 1.12 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CT, census tract; HOLC, Home Owners’ Loan Corporation; ICE, index of concentration at the extremes; RR, risk ratio.

aMassachusetts Cancer Registry data (2001–2015) for the 28 municipalities with HOLC rankings (1937–1938).

bTotal effect of HOLC ranking estimated using quasi-Poisson models with indirect age standardization and adjustment for sex/gender and race/ethnicity. All models used HOLC categories weighted by land area. All tests for statistical significance were 2-sided.

cControlled direct effect estimated using quasi-Poisson models with indirect age standardization and adjustment for sex/gender and race/ethnicity. Results represent the CT ICE stratum for racialized economic-segregation–specific HOLC effects, sex/gender- and race/ethnicity-adjusted. All models used HOLC categories weighted by land area. Tercile cutpoints based on the total distribution of CT ICE for race/ethnicity + income for the Massachusetts population (2001–2015) were 0.17 and 0.34.

dRelative to green + blue in CT ICE category T1 (tercile 1). This reminds us that the baseline risk of late-stage diagnosis is substantially elevated in green + blue areas in CT ICE category T2 + T3 (terciles 2 and 3).

eRelative to green + blue in CT ICE category T2 + T3. These are controlled direct effects.

fResidual disparity estimated using logistic regression for ICE for race/ethnicity + income (mediator) and quasi-Poisson models for the outcome. All models adjusted for race/ethnicity and sex/gender and used indirect age standardization. This residual disparity was estimated using the nonparametric simulation approach described by Imai et al. (41) and can be interpreted as the health disparity between persons in CTs with HOLC grades of yellow, red, or mixed or no grade and persons in CTs with HOLC grades of green + blue, if the ICE distribution of the persons in HOLC yellow, red, mixed, or no-grade CTs were set to a random draw from the distribution among HOLC green + blue CTs.

Table 2.

Total Effect and Controlled Direct Effect of Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Ranking on Women’s Breast and Cervical Cancer Stage at Diagnosis and Residual Disparity, Using Census Tract Index of Concentration at the Extremes for Racialized Economic Segregation as a Mediator, Massachusetts, 2001–2015a

| Breast Cancer | Cervical Cancer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI |

| Total Effect b | ||||

| HOLC ranking | ||||

| Green + blue (best; referent) | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yellow | 1.07 | 0.99, 1.15 | 0.90 | 0.69, 1.19 |

| Red | 1.07 | 0.98, 1.17 | 0.98 | 0.73, 1.33 |

| Mixed HOLC grades | 1.02 | 0.93, 1.11 | 0.76 | 0.54, 1.09 |

| No grade assigned | 1.03 | 0.96, 1.11 | 0.88 | 0.66, 1.17 |

| Controlled Direct Effect c | ||||

| HOLC ranking by CT ICE tercile | ||||

| ICE tercile 1 | ||||

| Green + blue | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yellow | 1.09 | 0.97, 1.22 | 0.76 | 0.44, 1.33 |

| Red | 1.15 | 0.95, 1.39 | 0.57 | 0.23, 1.40 |

| Mixed | 0.98 | 0.87, 1.10 | 0.89 | 0.48, 1.64 |

| No grade | 1.04 | 0.94, 1.14 | 0.75 | 0.48, 1.17 |

| ICE terciles 2 and 3 | ||||

| Green + blued | 1.23 | 1.08, 1.40 | 1.22 | 0.73, 2.01 |

| Green + blue | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yellowe | 0.94 | 0.84, 1.05 | 0.83 | 0.57, 1.21 |

| Rede | 0.94 | 0.83, 1.06 | 0.92 | 0.62, 1.37 |

| Mixede | 1.02 | 0.88, 1.17 | 0.67 | 0.42, 1.07 |

| No gradee | 0.94 | 0.84, 1.06 | 0.87 | 0.59, 1.29 |

| Residual Disparity f | ||||

| HOLC ranking | ||||

| Green + blue (best; referent) | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yellow | 1.03 | 0.95, 1.12 | 0.80 | 0.54, 1.11 |

| Red | 1.07 | 0.93, 1.21 | 0.72 | 0.00, 1.13 |

| Mixed HOLC grades | 0.99 | 0.90, 1.09 | 0.78 | 0.46, 1.15 |

| No grade assigned | 1.00 | 0.93, 1.09 | 0.80 | 0.62, 1.10 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CT, census tract; HOLC, Home Owners’ Loan Corporation; ICE, index of concentration at the extremes; RR, risk ratio.

aMassachusetts Cancer Registry data (2001–2015) for the 28 municipalities with HOLC rankings (1937–1938).

bTotal effect of HOLC ranking estimated using quasi-Poisson models with indirect age standardization and adjustment for sex/gender and race/ethnicity. All models used HOLC categories weighted by land area. All tests for statistical significance were 2-sided.

cControlled direct effect estimated using quasi-Poisson models with indirect age standardization and adjustment for sex/gender and race/ethnicity. Results represent the CT ICE stratum for racialized economic-segregation–specific HOLC effects, sex/gender- and race/ethnicity-adjusted. All models used HOLC categories weighted by land area. Tercile cutpoints based on the total distribution of CT ICE for race/ethnicity + income for the Massachusetts population (2001–2015) were 0.17 and 0.34.

dRelative to green + blue in CT ICE category T1 (tercile 1). This reminds us that the baseline risk of late-stage diagnosis is substantially elevated in green + blue areas in CT ICE category T2 + T3 (terciles 2 and 3).

eRelative to green + blue in CT ICE category T2 + T3. These are controlled direct effects.

fResidual disparity estimated using logistic regression for ICE for race/ethnicity + income (mediator) and quasi-Poisson models for the outcome. All models adjusted for race/ethnicity and sex/gender and used indirect age standardization. This residual disparity was estimated using the nonparametric simulation approach described by Imai et al. (41) and can be interpreted as the health disparity between persons in CTs with HOLC grades of yellow, red, or mixed or no grade and persons in CTs with HOLC grades of green + blue, if the ICE distribution of the persons in HOLC yellow, red, mixed, or no-grade CTs were set to a random draw from the distribution among HOLC green + blue CTs.

Figure 2.

Proportions of persons with late cancer stage at diagnosis (Massachusetts Cancer Registry data) in 28 Massachusetts municipalities with Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) rankings, by 1930s HOLC ranking and current census-tract index of concentration at the extremes (ICE) for terciles (T) of racialized economic segregation, 2001–2015. Proportions were indirectly standardized to the overall distribution of age, sex/gender, and race/ethnicity in the sample. A) Breast cancer; B) cervical cancer; C) colorectal cancer; D) lung cancer. Sex/gender and ICE tercile: △ female and T1; ▲ female and T2 + T3; □ male and T1; ■ male and T2 + T3; ○ total and T1;

total and T2 + T3. Operational definition of HOLC categories (x-axis): A + B, census tracts whose land area is ((100% A or (≥50% A and <100% A)) or (100% B or (≥50% B and <100% B))); C, census tracts whose land area is (100% C or (≥50% C and <100% C)); D, census tracts whose land area is 100% D or (≥50% D and <100% D). T1, tercile 1 (best); T2, tercile 2; T3, tercile 3 (worst).

total and T2 + T3. Operational definition of HOLC categories (x-axis): A + B, census tracts whose land area is ((100% A or (≥50% A and <100% A)) or (100% B or (≥50% B and <100% B))); C, census tracts whose land area is (100% C or (≥50% C and <100% C)); D, census tracts whose land area is 100% D or (≥50% D and <100% D). T1, tercile 1 (best); T2, tercile 2; T3, tercile 3 (worst).

Analyses that estimated the residual disparity additionally suggested that differences in risk of late-stage cancer by HOLC area would persist after a hypothetical intervention that set the CT ICE distribution in HOLC categories to a random draw from the CT ICE distribution among the green + blue HOLC areas. Noting that the residual disparity is a weighted average of mediator-stratum-specific controlled direct effects weighted to the distribution of CT ICE in the green + blue areas, for lung cancer among men, the residual disparity for men living in redlined areas increased to 1.10 (95% CI: 1.03, 1.17), reflecting the larger effect of living in a red HOLC area for men in T1 CTs. In contrast, for breast cancer, the point estimate for women in the yellow HOLC areas decreased to 1.03 (95% CI: 0.95, 1.12).

DISCUSSION

Our novel multicity investigation of HOLC regarding cancer inequities indicated that for the 28 Massachusetts municipalities with HOLC maps, risk of late stage at diagnosis for both breast and lung cancer during 2001–2015 was associated with historical redlining, independently from and also partly mediated by CT characteristics at the time of diagnosis. The results also suggest that, net of age, sex/gender, and race/ethnicity, residing in a previously redlined area imposed an elevated risk of late stage at diagnosis even for residents of CTs that contained a higher proportion of people with present-day economic and racial privilege, whereas the best historical HOLC grade was not protective for residents of CTs without such current privilege.

One limitation of our study is that estimates of associations may have been conservative, for 2 reasons: 1) our reliance on CT data and grouping of CTs homogenous for the given HOLC grade with those with ≥50% and <100% of this grade and 2) stage of diagnosis being conditional on having the disease, raising the possibility of collider bias due to unmeasured and unknown interactive effects of HOLC and other determinants of stage of diagnosis on cancer incidence. Our ICE metric for housing tenure had not been used previously, and results for this measure cannot be compared with those from other studies. Additionally, although we were able to include data for several potential individual-level confounders (age, race/ethnicity, and sex/gender), we lacked data on the cancer cases’ health insurance status, health facility at diagnosis, household- or individual-level socioeconomic position, and lifetime residential history. The relatively small number of cervical cancer cases, however, meant that our HOLC analyses for this site were underpowered, even though we could detect gradients using the contemporary ICE measures.

Additionally, despite the strength of analyzing HOLC maps for multiple cities, these cities nevertheless were geographically clustered around Massachusetts’ largest city, and results cannot be generalized to the rest of the state, including more rural areas. Nor can we offer a strictly causal interpretation of our results, given the implausibility of the stringent assumptions of no unmeasured confounding required for formal causal interpretation of mediation analyses (40, 41), but our results do offer a useful heuristic. Specifically, the different evidence we have assembled—regarding the HOLC total effects, effect modification by CT ICE, the differential distributions of current CT characteristics by HOLC grade, and the residual disparities—offers a starting point for analyzing causal pathways leading from the original HOLC designations to both current CT characteristics and health inequities.

Three lines of evidence lend credibility to our findings. First, among the small number of studies examining risk of late stage at diagnosis for cancer in relation to adverse racial segregation, elevated risk has been reported for breast, colorectal, and lung cancer (19, 20, 42, 43). Second, the relatively modest associations observed between current adverse CT characteristics and late stage at cancer diagnosis is compatible with evidence indicating 1) effective program implementation by Massachusetts initiatives to increase cancer screening for cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer and to reduce racial/ethnic health inequities in such screening (25, 27, 44), coupled with 2) policies to increase access to health-care insurance in Massachusetts, which have rendered Massachusetts the state with the lowest proportion of persons uninsured since 2006 (44–47)—and thus an apt locale in which to examine HOLC effects independent of insurance status.

Also lending support to our findings are the 4 extant empirical public health studies on historical redlining. The first, a 2017 cartographic analysis for Austin, Texas, juxtaposed the 1934 HOLC map with a 1951 map of tuberculosis incidence and 1950 US CT data on housing conditions (13). The authors reported higher concentrations of cases—and dilapidated housing—in the redlined areas (13). The second, a 2018 study which used the 1937 HOLC map for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and firearm violence data for 2013–2014, found higher incidence rate ratios for contemporary firearm violence when comparing redlined and other less “credit-worthy” areas to areas rated “best” by HOLC (incidence rate ratio = 13.1, 95% CI: 3.8, 47.4); the excess rate persisted (incidence rate ratio = 8.7, 95% CI: 2.2, 36.3) even after adjustment for 1940 CT sociodemographic characteristics (14). Among the 2 studies from 2019, 1 used longitudinal data from Michigan’s Detroit Neighborhood Health Study (2008–2013); those authors reported that for each 10-percentage-point increase in the land area of participants’ neighborhoods that had been historically redlined, people’s risk of poor self-rated health tended to increase, even after adjustment for individual-level age, sex/gender, race/ethnicity, and educational level and also neighborhood foreclosure rate (risk difference = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.06, 0.57) (15). The other study found that historical redlining in Baltimore, Maryland, more powerfully predicted clusters of alcohol outlets in 2016 than did contemporary census block-group demographic and economic characteristics; the odds ratio for such clusters for HOLC grade D (redlined) versus no HOLC grade was 9.37 (95% CI: 5.25, 16.71) (16).

In summary, our study’s findings add impetus for research investigating the long-term health implications of historical redlining and, by extension, other historical inequitable policies (7, 11, 12, 48). Such research is consonant with epidemiology’s longstanding focus on “person, time, and place” (49–53). The policy relevance of this type of research is high: In the case of historical redlining, data showing its contribution to contemporary health inequities, above and beyond current neighborhood conditions, can help inform debates over policy and resource allocation relevant to affirmatively furthering fair housing (1–3, 4, 11, 12, 48). Such data are also germane to new public exhibitions, videos, and journalism revealing the origins and continued impact of historical redlining on current societal inequities in health, housing, and well-being, which are promoting new public discussion and action about societal accountability and policy solutions (54–56). Epidemiologists can fruitfully investigate how past and present policy decisions can have spatial and social ramifications with long-lasting impacts on health inequities.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts (Nancy Krieger, Emily Wright, Jarvis T. Chen, Pamela D. Waterman); and Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts (Eric R. Huntley, Mariana Arcaya).

This work was funded by the American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor Award (to N.K.).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rothstein R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Metzger MW, Webber HS, eds. Facing Segregation: Housing Policy Solutions for a Stronger Society. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nelson RK, Winling L, Marciano R, et al. Mapping inequality: redlining in New Deal America, 1935–1940 In: Nelson RK, Ayers EL, eds. American Panorama: An Atlas of United States History. Richmond, VA: Digital Scholarship Laboratory, University of Richmond; 2019. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=4/36.71/-96.93&opacity=0.8. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aaronson D, Hartley DA, Mazumder B. The Effects of the 1930s HOLC “Redlining” Maps. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2017. (FRB of Chicago Working Paper no. WP-2017-12) https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3038733. Last revised October April 29, 2020. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Omi M, Winant H. Racial Formation in the United States. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kramer M. Residential segregation and health In: Duncan D, Kawachi I, eds. Neighborhoods and Health. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018:321–356. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krieger N. Discrimination and health inequities In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour M, eds. Social Epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014:63–125. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Services. 1992;22(3):429–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(4):254–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ellen IG, Steil J, eds. The Dream Revisited: Contemporary Debates About Housing, Segregation, and Opportunity. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harris AP, Pamukcu A The civil rights of health: a new approach to challenging structural inequality [published online ahead of print April 24, 2019]. UCLA Law Rev. (doi: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3350597). Accessed March 16, 2020.

- 13. Huggins JC. A cartographic perspective on the correlation between redlining and public health in Austin, Texas—1951. Cityscape. 2017;19(2):267–280. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jacoby SF, Dong B, Beard JH, et al. The enduring impact of historical and structural racism on urban violence in Philadelphia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McClure E, Feinstein L, Cordoba E, et al. The legacy of redlining in the effect of foreclosures on Detroit residents’ self-rated health. Health Place. 2019;55:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Trangenstein PJ, Gray C, Rossheim ME, et al. Alcohol outlet clusters and population disparities. J Urban Health 2020;97:123–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nardone A, Thakur N, Balmes JR Historic redlining and asthma exacerbations across eight cities of California: a foray into how historic maps are associated with asthma risk [abstract] Presented at the American Thoracic Society 2019 International Conference, Dallas, Texas, May 17–22, 2019 10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2019.199.1_MeetingAbstracts.A7054. Accessed March 16, 2020. [DOI]

- 18. Musser B. Sick and segregated: the association between childhood asthma and historic housing discrimination in Kansas City [abstract] Presented at the American Public Health Association 2019 Annual Meeting and Expo, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November 2–6, 2019 https://apha.confex.com/apha/2019/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/439309. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Landrine H, Corral I, Lee JGL, et al. Residential segregation and racial cancer disparities: a systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(6):1195–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zahnd WE, McLafferty SL. Contextual effects and cancer outcomes in the United States: a systematic review of characteristics in multilevel analyses. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(11):739–748.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. White MC, Babcock F, Hayes NS, et al. The history and use of cancer registry data by public health cancer control programs in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123(suppl 24):4969–4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. North American Association of Central Cancer Registries Standards for Completeness, Quality, Analysis, Management, Security and Confidentiality of Data . Springfield, IL: North American Association of Central Cancer Registries; 2008. https://www.naaccr.org/standards-for-completeness-quality-analysis-and-management-of-data/. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; Cancer Trends Progress Report: Stage at Diagnosis. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2019. (Data up to date as of February 2019). https://progressreport.cancer.gov/diagnosis/stage. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Massachusetts Cancer Registry Massachusetts Cancer Registry Boston, MA: Massachusetts Cancer Registry; 2020. https://www.mass.gov/massachusetts-cancer-registry. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Massachusetts Cancer Registry Data Brief: Trends in Cancer Incidence (2003–2013) and Mortality (2003–2014) for Four Major Cancers. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Cancer Registry; 2015. https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2018/03/16/registry-trends-incid-2003-13-mort-2003-14.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, et al. , eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975–2015. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2017. (Based on November 2017 SEER data submission) https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/. Updated September 10, 2018 Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sabik LM, Bradley CJ. The impact of near-universal insurance coverage on breast and cervical cancer screening: evidence from Massachusetts. Health Econ. 2016;25(4):391–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. ESRI ArcGIS, Release 10.4.1 Redlands, CA: ESRI; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter? The Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(5):471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Painting a truer picture of US socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health inequalities: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):312–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bureau of the Census, US Department of Commerce Census 2000. Summary File 3 Dataset. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2002. https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2000/dec/summary-file-3.html. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bureau of the Census, US Department of Commerce American Community Survey (ACS). 5-Year Estimate Releases for 2008–2015. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2011–2018. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. SAS Institute, Inc. SAS, Version 9.4 Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 2019. https://www.sas.com/en_us/software/sas9.html. Accessed November 16, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Massey DS. The prodigal paradigm returns: ecology comes back to sociology In: Booth A, Crouter A, eds. Does It Take a Village? Community Effects on Children, Adolescents, and Families. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krieger N, Waterman PD, Spasojevic J, et al. Public health monitoring of privilege and deprivation using the index of concentration at the extremes (ICE). Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):256–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krieger N, Feldman JM, Kim R, et al. Cancer incidence and multilevel measures of residential economic and racial segregation for cancer registries. JNCI Cancer Spectrum. 2018;2(1):pyk009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Release 3.5.3) Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bureau of the Census, US Department of Commerce Statistical Brief: Poverty Areas. (Report no. SB/95-13) Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 1995. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1995/demo/sb95-13.html. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Office of Research on Women’s Health, National Institutes of Health Sex & Gender. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2020. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40. VanderWeele T. Explanation in Causal Inference: Methods for Mediation and Interaction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods. 2010;15(4):309–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scally BJ, Krieger N, Chen JT. Racialized economic segregation and stage at diagnosis of colorectal cancer in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2018;29(6):527–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Smith BP, Madak-Erdogan Z. Urban neighborhood and residential factors associated with breast cancer in African American women: a systematic review. Horm Cancer. 2018;9(2):71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Clark CR, Soukup J, Riden H, et al. Preventive care for low-income women in Massachusetts post-health reform. J Womens Health. 2014;23(6):493–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Blue Cross/Blue Shield Foundation of Massachusetts A History of Promoting Health Coverage in Massachusetts . Boston, MA: Blue Cross/Blue Shield Foundation of Massachusetts; 2018. https://bluecrossmafoundation.org/publication/history-promoting-health-coverage-massachusetts. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Center for Health Information and Analysis, Commonwealth of Massachusetts Massachusetts Health Insurance Survey (2017). Boston, MA: Center for Health Information and Analysis; 2019. http://www.chiamass.gov/massachusetts-health-insurance-survey/. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barnett JC, Berchick ER. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2017. (US Census report no. P60-264) Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2018. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-264.html. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kelleher K, Reece J, Sandel M. The Healthy Neighborhood, Healthy Families initiative. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):pii: 201802621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sydenstricker E. Health and Environment. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1933. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Morris JN. Uses of Epidemiology. 1st ed. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: E&S Livingston; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lilienfeld A. Foundations of Epidemiology. 1st ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Krieger N. Epidemiology and the People’s Health: Theory and Context. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weiss N, Koepsell TD. Epidemiologic Methods: Studying the Occurrence of Illness. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Designing the WE Undesign the Red Line. New York, NY: WE; 2019. https://www.designingthewe.com/undesign-the-redline. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lopez M, Rothstein R, YouToCanWoo. Segregated by Design [video] Austin, TX: Silkworm Studio; 2019. https://www.segregatedbydesign.com/. Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Badger E. Self-fulfilling prophecies: how redlining’s racist effects lasted for decades New York Times. August 24, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/24/upshot/how-redlinings-racist-effects-lasted-for-decades.html. Accessed March 16, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.