Abstract

We conducted a survey of licensed psychologists at two weeks and again at six months after the declaration of a national emergency related to the COVID-19 pandemic. This article describes the results of the second survey conducted approximately six months after the crisis began. The rapid shift to telepsychological services seen in the first survey in the pandemic has solidified in the second survey. More providers reported delivering a larger percentage of services via telepsychology than early in the pandemic. The majority of respondents do not anticipate resuming in-person services until after a vaccine is made available, although a consistent minority reports ongoing in-person service provision. A majority reported their patients had appropriate access to internet and telepsychological service platforms, although one-fifth of respondents reported their patients had difficulty accessing such services. Early concerns about technological or regulatory problems involved in telepsychology are no longer evident. Most respondents indicated they will continue to use telepsychological services for the delivery of some of their psychological services after the pandemic ends. Forty-five percent knew of individuals who contracted the disease, 13% knew someone who died of the disease, and 2% reported contracted the disease themselves.

Clinical Challenge

On March 20, 2020, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared a national public health emergency in response to infections due to SARS-CoV-2, a novel coronavirus. Six days later, on March 26, 2020, the National Register of Health Service Psychologists (“The Register”) partnered with the American Insurance Trust (“The Trust”) to launch the first national survey of the effects of the burgeoning COVID-19 pandemic on the practices of licensed psychologists in their respective memberships. Those results are detailed in Sammons et al. (2020). In brief, that survey of 3,038 American psychologists found a remarkably rapid shift from in-person practice to telepsychological service provision. We also found significant early effects of the pandemic on psychologists’ caseloads, with 59% reporting a decline in caseload.

At approximately the same time, Marra et al. (2020) surveyed a smaller group (n = 266) of American neuropsychologists who did not work in government settings. As in our survey, the majority of their respondents worked in private practice settings, and the majority of respondents reported reduced workloads or pay. Respondents in that survey reported a wholesale shift to distance service provision, with 62% of their respondents reporting working entirely remotely (those authors also conducted a second survey that enhanced their initial sample size and provided some elaboration; broadly speaking, results were consistent across both surveys).

In mid-May 2020, Pierce et al. (2020) conducted a survey of licensed psychologists in clinical practice in the US. They used a variety of recruitment methods, generally focusing on professional directories or websites. Eligibility was limited to licensed US psychologists with active caseloads. Their final sample comprised 2,619 such psychologists, who possessed an average of 24.22 years in practice, with the majority (70%) in individual or group practice. These researchers found that while 46% of respondents had not used telepsychology before the pandemic, 96% used it to at least some extent after the crisis began. Seventy-eight percent reported using telepsychology for 90–100% of their practice, and 89% stated their intent to continue to use telepsychology after the pandemic ended.

Other surveys in April, May, and June examined the effects of the pandemic on specialty services. These included, as a limited sampling, child custody evaluations (Dale & Smith, 2020), HIV services (Qiao et al., 2020), and intellectual and developmental services (Jeste et al., 2020). Substance abuse treatments were also examined. All found the same pattern for a decrease in available and delivered services in the months immediately after the declaration of the pandemic. Many of these specialized services required more “hands-on” aspects, and alternative means of providing these services remained under development in the early months.

Current Survey Method

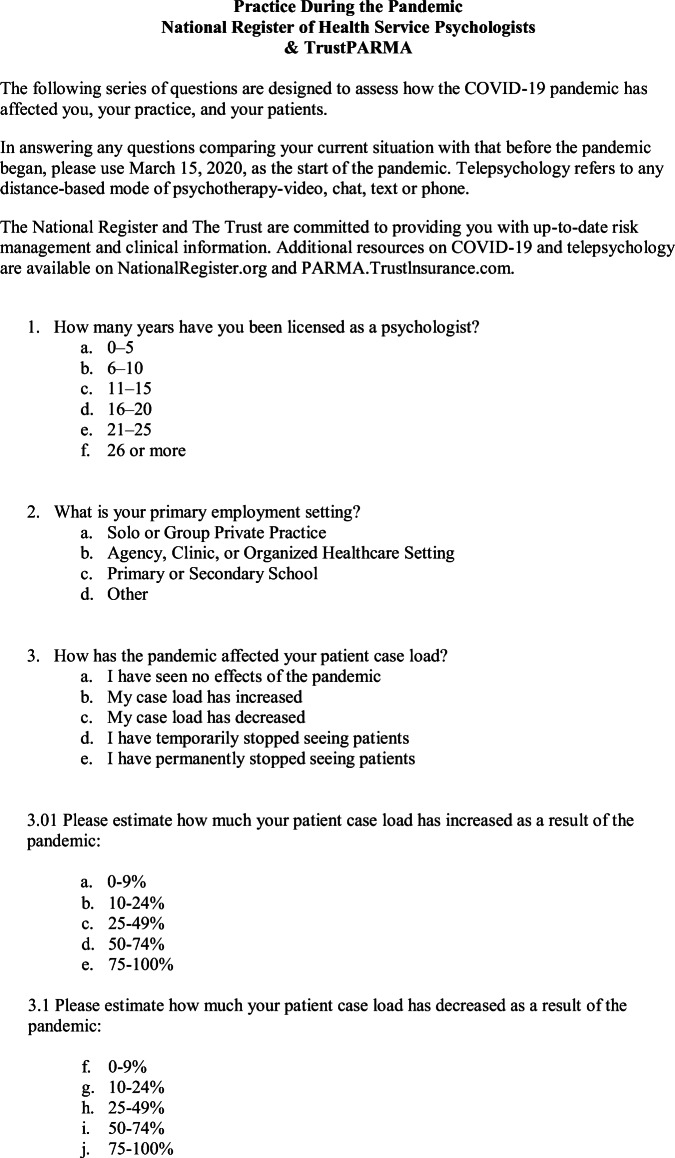

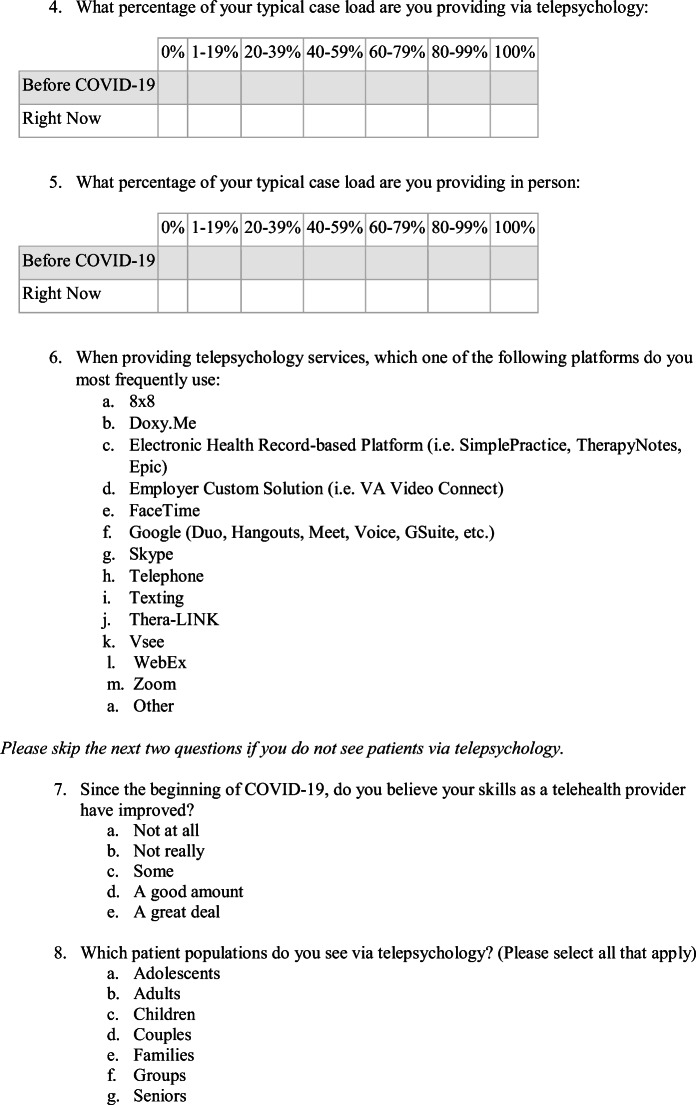

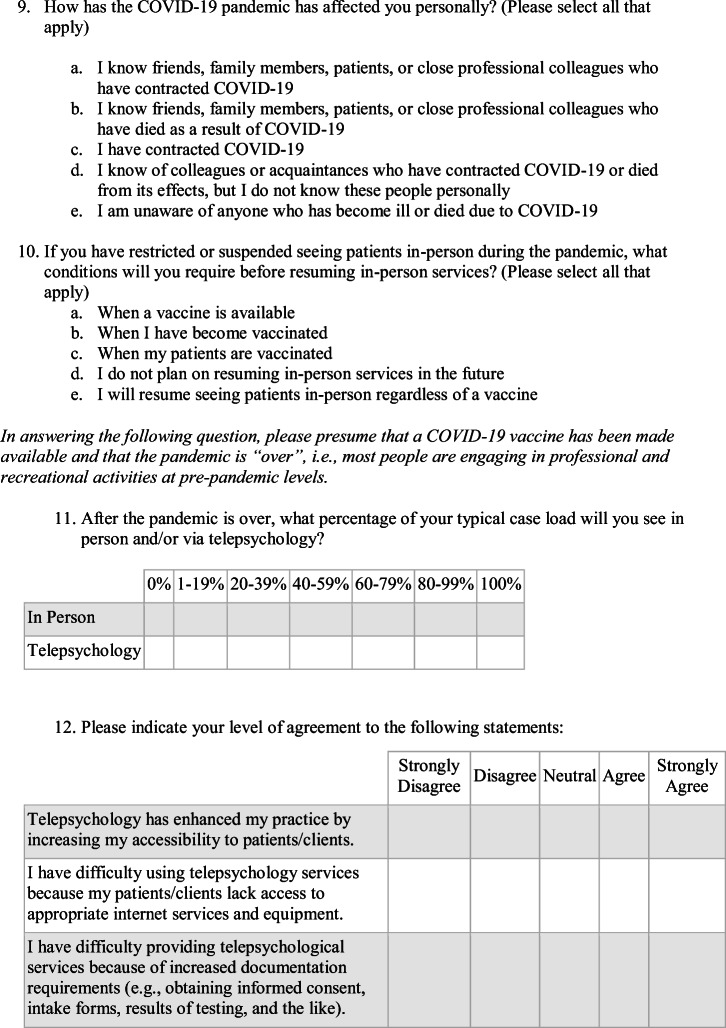

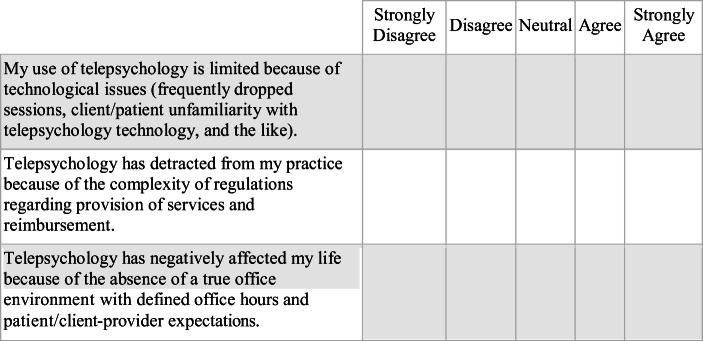

Approximately six months into the pandemic, we desired to further ascertain the ongoing effects of COVID-19 on psychological practice. Accordingly, we again asked members of The Register and The Trust to respond to a brief survey (Appendix A), which was slightly modified from the first one.

The survey was distributed via email solicitation to licensed psychologist members of The Register and policyholders insured by The Trust. The survey was open for 21 days, from August 26 to September 15, 2020. Email solicitations were opened by 23,474 recipients. Of these, 3,209 submitted usable responses, for an overall response rate of 13.6%. Total number of email opens and response rates were close to those observed during our initial survey (22,392 and 13.6%, respectively) and was deemed acceptable for a rapid response email survey of this nature.

The current survey was comprised of 12 questions, one question required a Likert-type response to eight individual stems assessing experiences regarding the use of telepsychology. Because not all respondents answered all questions, response rates to each question are given where applicable, where n = the respondents to any one question, with percentages based on that number. As with our original survey, however, generalizability concerns mandate that caution be used in interpreting data presented herein.

Results of Second Survey

Respondents tended to be more senior practitioners, although a roughly bimodal distribution was observed, with approximately 32% of respondents being in practice for fewer than 15 years and 49% being in practice for more than 26 years. An overwhelming majority of respondents were in private individual or group practice (74%, n = 3,196), with only 22% reporting employment in an agency, clinic, other organized healthcare setting, or primary or secondary school.

Key Findings

Pandemic Effects on Respondents

COVID-19 has had remarkable personal and professional effects on respondents. Almost half (45%, n = 3,164) of respondents knew of friends, family members, or patients who had contracted the disease, and 13% reported knowing someone in these categories who had died as a result of COVID-19. Sixty-one respondents (2%) revealed that they had contracted the disease.

Shift to Telepsychology

In our initial survey in the spring, we noted a rapid shift among all provider groups to telepsychological service provision (Fig. 1). Pre-pandemic, a high percentage of psychologists provided no or very few services via telepsychology. A full 89% of respondents saw no patients via telepsychology; only 11% saw any patients via telepsychology. A few weeks into the pandemic, the situation was almost completely reversed. Seventy-five percent of all respondents saw at least half of their patients via telepsychology and over half (53%) were providing the entirety of their services via telepsychology.

Fig 1.

March: Percent of psychologists' caseload seen via telepsychology over time

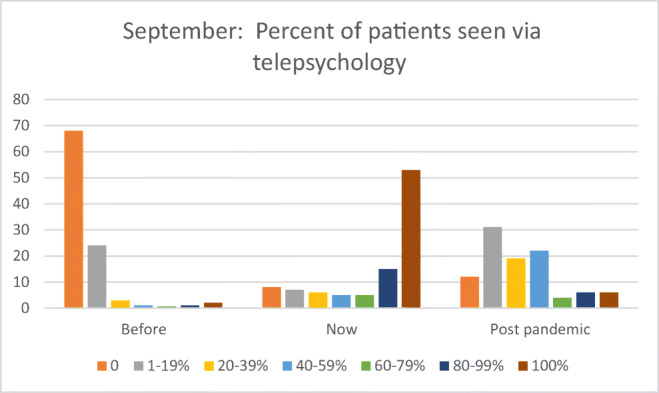

We saw a somewhat different picture regarding telepsychological service provision six months later (Fig. 2). In our September survey, 68% of respondents reported a rapid shift from seeing no patients via telepsychology pre-pandemic to seeing all or almost all via telepsychology. In fact, 53% of respondents stated seeing their entire caseload via telepsychology. Sixteen percent of respondents reported seeing up to one-fifth of their caseload in person; and a very small minority (5%) of respondents have continued to see their entire caseload in person. Further quintile breakdowns are provided in Fig. 2.

Fig 2.

September: Percent of patients seen via telepsychology

Future Practice Plans

Looking ahead to an eventual post-pandemic time, our respondents indicated that the shift to telepsychological services is likely to be permanent to some degree. While few respondents anticipated seeing 100% of their caseloads via telepsychology after the pandemic (6%, n = 3,002), 16% anticipated seeing the majority of patients via telepsychology in the future, and almost 90% of respondents anticipated at least some telepsychological service provision after the pandemic. These results were in keeping with a similar question posed during our March survey, when 84% of respondents anticipated seeing as many as half of their future caseload via telepsychology.

Return to In-Person Care

The majority (77%, n = 2,657) of respondents reported that they will not resume in-person services until a vaccine is available and they or their patients have become vaccinated. Sixteen percent of respondents reported they would resume in-person services regardless of availability of a vaccine. This number may in part reflect the responses of those who have continued to see patients in-person throughout the pandemic.

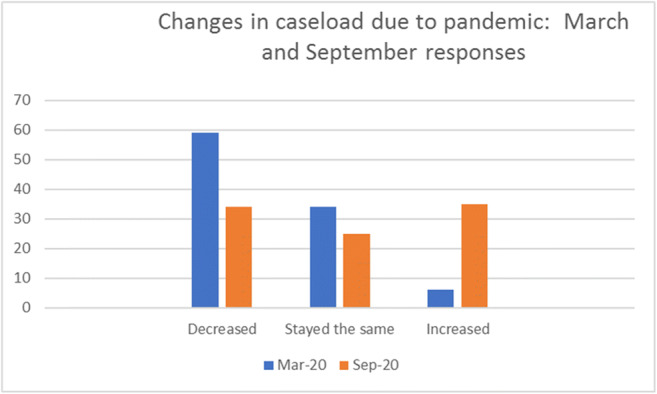

Changes in Caseloads

Psychologists’ caseloads have been variably affected by the pandemic. For some, the changes have been dramatic, particularly for those experiencing a drop in caseload. In March, 59% of respondents noted a drop in caseload (Fig. 3). By September, the pattern was substantially different. Similar numbers of respondents reported pandemic-related increases in caseload (34%, n = 1,070) or a pandemic-related decrease in caseload (35%, n = 1,107). Twenty-five percent of respondents noted no change in caseload.

Fig 3.

Changes in caseload due to pandemic: March and September responses

Of those reporting an increase in caseload, most (56%) saw an increase of up to 25%, although a minority (14%) reported caseload increases of up to 50%. Only 5% reported increases of more than 50%.

Of those reporting a decrease, the majority (45%) saw a decrease of 10–24% in their patient load. Fewer respondents (28%) noted a decrease of 25–49% of patients, and 15% reported decreases of between half and three-quarters of their previous caseload.

Means of Telepsychology Delivery

Doxy.me and Zoom continue to be the most commonly used telepsychology platforms. Thirty percent of respondents (n = 3,041) use Doxy.me, 25% use Zoom, and 10% used a telepsychology platform integrated into an electronic health record. The remainder are relatively evenly divided between various platforms.

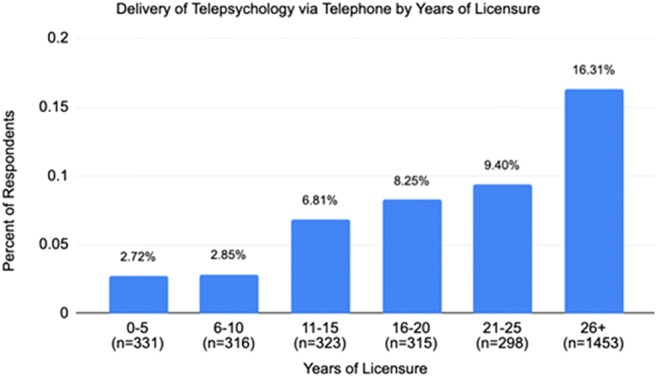

One finding of interest is that provision of services via telephone (e.g., audio only) increased as a function of years in practice. Figure 4 illustrates that psychologists with 26 or more years of experience were significantly more likely to report that they most frequently use a telephone to provide telepsychological services compared to their earlier career peers (χ2(5, n = 331) = 727.5, p < .01).

Fig 4.

Delivery of telepsychology via telephone by years of licensure

Likewise, psychologists with 26 or more years of experience were significantly more likely to report that they most frequently use FaceTime to provide telepsychological services compared to their more early career peers (χ2(5, n = 156) = 319.6, p < .01). Psychologists earlier in their careers appeared more likely to report using electronic health record platforms such as SimplePractice or TherapyNotes (2(5, n = 298) = 28.8, p < .01).

Confidence in Use of Technology

The overwhelming majority of respondents believed that their skills in using telepsychology had improved to at least some degree since the pandemic began. Only 11% of respondents did not report an improvement in skills, and 60% reported that their skills had improved a good amount or a great deal.

Fifty-two percent of respondents (n = 3,120) agreed or strongly agreed with a statement that their patients were as accepting of telepsychological provision of services as they were of in-person services, but 24% noted disagreement or strong disagreement with this statement. Twenty-two percent of respondents also believed that the absence of an in-office environment had negatively affected their lives (n = 3,096), though the majority (58%) disagreed or strongly disagreed with this observation.

Many respondents, however, did not feel comfortable providing telepsychological services to patients deemed at a higher risk for suicidal behavior (Fig. 5). Sixty-four percent (n = 3,120) disagreed or disagreed strongly to a survey item stating, “I feel comfortable providing telepsychological services to patients who are at higher risk for suicidal behavior.” Only 4% of respondents reported strongly agreeing with comfort at providing telepsychology services to such patients.

Fig 5.

I feel comfortable providing telepsychological services to patients who are at higher risk for suicidal behavior

Discussion

For most psychologists, practice has rebounded and telepsychology has become an enduring component of the practice landscape since the national emergency was declared in March 2020. In March, three of out five respondents reported a decline in caseload, with only 6% reporting an increase. In September, one third of respondents reported an increase in caseload, while one third also reported a decline. Since almost all respondents have shifted to telepsychological service provision since the pandemic began, the disparity in caseloads is likely not ascribable to difficulty in establishing virtual connectivity with patients. It may, however, reflect varying levels of proficiency or provider comfort in using telepsychology.

The pandemic has definitively reshaped the future of practice landscape. In March, 73% of psychologists anticipated using telepsychology for at least some of their patients in one year; in September, 88% reported their intent to continue to use telepsychology after the pandemic. Most respondents believe that telepsychology will be an enduring component of their practices, even after the current pandemic ends. While we can no longer presume the pandemic will be over in one year, we can use this as a rough marker to describe ‘post-pandemic’ intention.

In a similar fashion, levels of patient current acceptance and comfort with telepsychological interventions, as reported by their psychologists, seem to have grown, at least as estimated by psychologists’ use of telepsychology. In March, 86% of respondents believed that 50% or more of their patients did not like telepsychology. In September, 52% of respondents reported that half or more of their patients were accepting of telepsychology. Similarly, regarding respondents’ acceptance, 89% of those responding in September reported increasing comfort with their own telepsychology skills, with 63% of these estimating that their telepsychology skills had improved a good amount or a great deal. In contrast, only 58% of March respondents described feeling somewhat or extremely prepared to use telepsychology. We are not surprised by the rapid acceptance of telepsychology by patients, as earlier studies (Kruse et al., 2017) suggested that patients are both accepting of distance modalities and are less concerned about potential privacy breaches than providers.

We are equally unsurprised at provider acceptance of telepsychology. We earlier speculated that extensive discussion of telepsychology over the past two decades has made this shift palatable to psychologists, and provision of additional training since the start of the pandemic has likely been valuable in providing support. At six months, we remain unaware of a significant increase in telepsychology-related malpractice actions. We are hopeful that this suggests that despite the rapidity with which psychologists embraced distance service provision, they have benefitted from prior discussions of risks associated with telepsychology and have been characteristically prudent in adopting this new technology.

Some of the areas of concern in using telepsychology platforms we discovered in our earlier survey persist. Certain types of evaluation are still difficult or impossible to perform using virtual means, and numerous standardized testing instruments are still not amenable to distance administration, either due to their nature or to an ongoing lack of normed data. Also, in spite of broad acceptance, some patients and providers may continue to be either unwilling to engage in telepsychological service provision or lack the means or training to do so. Since most of our respondents expressed discomfort in providing telepsychology to high suicide risk patients, and since such patients are undoubtedly likely to seek telepsychological services, we believe that future training efforts should be focused on effective clinical and risk management interventions for suicidal patients. We are also concerned about our finding that a sizable minority of those who have been in practice for over 26 years were significantly more likely to use Apple’s FaceTime as a telepsychology medium. Controversy exists as to whether FaceTime is a HIPAA-compliant platform, as Apple does not enter into Business Associate’s Agreements with providers. We encourage caution for those using telepsychology platforms that may not be HIPAA-compliant.

Our findings are remarkably similar to those of another large survey of psychologists (Pierce et al., 2020). Although our recruitment methods differed, both sets of respondents tended to be more senior psychologists working in individual or group private practice settings, and the response rates for the two surveys were roughly the same. Striking similarities were apparent in their findings of a rapid shift to telepsychological services, being essentially identical to those in our first study (collected approximately two months earlier). Likewise, the percentage of respondents indicating they would continue to use telepsychology after the pandemic was essentially identical (87.73% in our study in March versus 89.19% in Pierce study). The similarity of these findings lend confidence to our supposition that our respondents were broadly representative of practicing psychologists in the US and that their practice patterns also reflected those of most practitioners.

We did not survey patients directly regarding their experiences using telepsychology, nor did we survey patients directly regarding their access to and fluency with virtual psychological care. We are keenly aware of numerous studies describing a “digital divide” limiting access to virtual healthcare services during the pandemic. Ramsetty and Adams (2020) noted that while they developed pandemic-related web-based access at clinics serving economically disadvantaged patients, lack of digital access required continuation of in-person services. Analyses of such divides often focus on ethnicities and socioeconomic status, but at least some have reported an age-related digital divide separating geriatric from younger patients (Uchechi et al., 2019). Health literacy, income, and social isolation have also been found to predict electronic access to healthcare information (Estacio et al., 2019).

That said, 69% of our provider respondents reported that telepsychology enhanced their access to patients. Conversely, 21% reported difficulty using telepsychology because of lack of patient access to internet services and equipment. Thus, while perhaps not as striking as gaps noted in other surveys, a digital divide does seem to be a factor limiting telepsychological service provision to a substantial minority of patients.

Our survey was limited by a nonrandom sampling method. We used a convenience sample of members of the sponsoring organizations. Findings, however, are consistent with the results of another survey using a different recruitment method, so we believe our results may represent the opinions of the field at large. Our surveys were designed as rapid response instruments, so they were limited in scope and in the ability of respondents to include free text fields. Responses to the March and September surveys are often not directly comparable, as questions were phrased differently in order to accommodate the need for brevity.

Wrapping Up & Reflection

Our findings from two sampling times in the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate a consistent shift from in-person to distance psychological service provision. This shift has been in place for six months and is likely to be permanent. Provider acceptance of telepsychological services has increased. Not surprisingly, psychologists’ comfort with using telepsychological service has increased, likely as a result of familiarity with the technology, additional training, and practice adaptations. Most of our respondents indicated that after the pandemic, they expect to provide a mix of both in-person and distance services. Our findings are consistent with those of other snapshot surveys taken at various points during the pandemic.

Healthcare delivery in the future will include a mix of telehealth services along with in-person services. We will next begin the process of understanding the limits of remote service delivery and the comparative advantages and disadvantages of remote care versus in-person care. This will include the elements that are critical for patient access to and acceptance of given forms of service. The factors in the provision of both in-person and remote care which are most essential to safe and effective services will be an important next step in developing our knowledge for providing optimal care for all.

Biographies

Morgan T. Sammons

, PhD, ABPP, is the executive officer of the National Register of Health Service Psychologists. He is a retired Navy captain and was formerly the U.S. Navy’s specialty leader for clinical psychology.

Gary R. VandenBos

, PhD, is the senior professional consultant at the National Register of Health Service Psychologists. He previously served as the publisher of the American Psychological Association for over 30 years. He is the coauthor of Leaving It at the Office: A Guide to Psychotherapist Self-Care, Second Edition.

Jana N. Martin

, PhD, is the CEO of The Trust. Previously, she was a cochair of the Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists and a coeditor of A Telepsychology Casebook: Using Technology Ethically and Effectively in Your Professional Practice.

Daniel M. Elchert

, PhD, is a professional consultant at the National Register of Health Service Psychologists. He is a licensed clinical psychologist and statistician who completed his doctoral training at the University of Iowa and his postdoctoral fellowship at the American Statistical Association. He hosts the National Register’s podcast series, The Clinical Consult.

Appendix

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Dale, M. D. & Smith, D. (2020). Making the case for videoconferencing and remote child custody evaluations (RCCEs): The empirical, ethical, and evidentiary arguments for accepting new technology. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. Advance online publication. 10.1037/law0000280

- Estacio EV, Whittle R, Protheroe J. The digital divide: Examining socio-demographic factors associated with health literacy, access and use of internet to seek health information. Journal of Health Psychology. 2019;24:1668–1675. doi: 10.1177/1359105317695429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste, S., Hyde, C., Distefano, C., Halladay, A., Ray, S., Porath, M., Wilson, R. B., & Thurm, A. (2020). Changes in access to educational and healthcare services for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities during covid-19 restrictions. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. Advance online publication. 10.1111/jir.12776 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, Tran L, Vela J, & Brooks M. (2017). Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open. 7(8):e016242. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marra DE, Hoelzle JB, Davis JJ, & Schwartz ES. (2020). Initial changes in neuropsychologists clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study. Clinical Neuropsychology.29:1–16. 10.1080/13854046.2020.1800098. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pierce, B. S., Perrin, P. B., Tyler, C. M., McKee, G. B., & Watson, J. D. (2020). The COVID-19 telepsychology revolution: A national study of pandemic-based changes in US mental health care delivery. American Psychologist, published online at 10.1037/amp0000722 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Qiao, S., Li, Z., Weissman, S., Li, X., Olatosi, B., Davis, C., & Mansaray, A. B. (2020). Disparity in hiv service interruption in the outbreak of covid-19 in south carolina. AIDS and Behavior.27:1–9. 10.1007/sl0461-020-03013-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ramsetty A, Adams C. Impact of the digital divide in the age of COVID-19. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2020;27:1147–1148. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammons MT, VandenBos GR, Martin JN. Psychological Practice and the COVID-19 Crisis: A Rapid Response Survey. J Health Serv Psychol. 2020;46:51–57. doi: 10.1007/s42843-020-00013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchechi, A., P Chebli, P., Ruggiero, L., & Muramatsu, N. (2019). The Digital Divide in Health-Related Technology Use: The Significance of Race/Ethnicity. The Gerontologist, 59, pp. 6–14, 10.1093/geront/gny138 [DOI] [PubMed]