Abstract

Background

Lung squamous-cell carcinoma (SqCC) is the second most common histology in non-small-cell lung carcinomas (NSCLCs). The treatment options for advanced lung SqCC are still an unmet medical need. Apatinib, a small-molecule inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2), is beneficial in the therapy of advanced NSCLC patients. This study aimed to preliminarily assess the efficacy and safety of low-dosage apatinib in patients with advanced lung SqCC.

Methods

In this single-arm, open-label, investigator-initiated phase II prospective study (ChiCTR1800019808), we enrolled patients aged 54–80 years with platinum-refractory or chemotherapy rejected advanced lung squamous-cell carcinoma. Key exclusion criteria included major blood vessel involvement and gross hemoptysis with an amount of more than 20 mL. Apatinib at an initial dose of 250 mg was administered to patients once daily until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, withdrawal, or death. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS) in all patients. We assessed the adverse events according to the treatment received.

Results

Thirty-eight patients were enrolled between June 11, 2015 and August 29, 2018. Two patients failed to evaluate treatment efficacy for personal reasons, and thus 36 patients were eligible for evaluation of tumor response to apatinib. Median PFS was 4.9 months (95% CI: 3.0–6.8 months). Six patients achieved partial response (PR); the objective response rate (ORR) was 16.7% (6/36), and the total disease control rate (DCR) was 77.8% (28/36). Followed up to March 2020, 35 of the 38 patients were dead, and the 1-year survival rate was 21.1% (8/38). The median overall survival (OS) was 6.9 months (95% CI: 5.2–8.5 months). The most common adverse events included fatigue (50.0%), hypertension (42.1%), proteinuria (23.7%), loss of appetite (23.1%) and hand-foot reaction (21.1%). No grade 4 adverse effect or drug-related mortality occurred.

Conclusions

Low-dose apatinib monotherapy might be an option for patients with advanced lung squamous-cell carcinoma.

Keywords: apatinib, lung squamous-cell carcinoma, VEGF, efficacy, safety

Introduction

Lung cancer ranks first globally in morbidity and mortality rates among cancers. Lung squamous-cell carcinoma (SqCC), which is included in non-small cell carcinoma (NSCLC), accounts for 25–30% of lung cancer cases.1 Unlike the success obtained in the therapy of adenocarcinoma, the treatment options in advanced lung SqCC are still limited due to the lack of driver mutations and a worse prognosis.2 In patients with advanced lung SqCC, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the first-line standard treatment option. Unfortunately, although the chemotherapy regimen has been updated in the past 30 years, the median survival time is only 1 year for patients with stage IIIB or IV lung SqCC.3

Folkman was the first to propose the theory of tumor angiogenesis and the therapeutic conception and mechanism for anti-angiogenesis.4 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors, especially VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2), are predominantly responsible for angiogenic signaling,5,6 which is an essential step in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis.7 Antibodies against VEGF or VEGFR, bevacizumab and ramucirumab were suggested for addition to chemotherapy for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) without driver mutation.8,9 Of note, bevacizumab is not approved for the treatment of lung SqCC because of the risk of hemorrhage.10,11 To date, scarce evidence exists for the application of monotherapy with antiangiogenesis drugs as second- or further-line therapy for advanced lung SqCC.

As an oral small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) available in mainland China, apatinib, which selectively binds to and inhibits VEGFR-2, has a significant effect on advanced gastric and breast cancers.12–14 Recent studies showed the efficiency of apatinib in advanced NSCLC patients.15,16 In the present pilot investigation, we aimed to explore the efficacy and safety of low-dose apatinib monotherapy in Chinese patients with advanced lung SqCC.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

We conducted a single-arm, open-label, investigator-initiated phase II prospective study at the Affiliated Changzhou No.2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Changzhou, China) and Lianyungang No.2 People’s Hospital (Lianyungang, China). Patients aged 54–80 years, who had platinum-refractory (defined as progression during the initial platinum-based treatment) advanced lung squamous-cell carcinoma (III–IV stage), were eligible to take part in the study. Patients who refused chemotherapy were also eligible.

Key exclusion criteria were major blood vessel involvement and gross hemoptysis with an amount of more than 20 mL. Patients of any one or more of the following conditions were also excluded: severe liver failure, severe kidney failure, and class III or IV cardiac insufficiency.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Changzhou No.2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, and the patients selected for the study signed consent forms.

Procedures

Patients were administered apatinib at an initial dose of 250 mg once daily and would not stop until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, withdrawal, or death.

Dose modifications, including dose interruptions and dose reductions, were allowed for the management of adverse events. Repeated dose interruptions were permitted as required, for a maximum of 14 days on each occasion.

Two dose reductions were permitted for apatinib (250 mg and 125 mg taken on alternate days, and 125 mg once daily) in the event of toxicity. For grade 4 non-hematological toxicities, apatinib was delayed until recovery to grade 1 or better and then resumed with a reduction of one dose. At the first occurrence of grade 3 non-hematological and grade 3 or 4 hematological toxicities, apatinib was delayed until recovery to grade 1 or below non-hematological and grade 2 or below hematological toxicities, and then treatment was resumed at the same dose. On the second occurrence of grade 3 non-hematological and grade 3 or 4 hematological toxicities, patients underwent one dose reduction (to either 250 mg and 125 mg taken on alternate days or 125 mg once daily, depending on the dose level patients were on when the toxicities occurred). Dose reductions were also recommended for intolerable grade 2 events if investigators considered dose reduction necessary.

Measurable disease was assessed and documented before treatment. Tumor response according to RECIST 1.1 was assessed by investigators using CT scans after 28 days of apatinib monotherapy, and subsequently every 2 months until disease progression was confirmed. Adverse events were evaluated according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 4.0 (CTC 4.0) and were assessed throughout the treatment cycles.

Outcomes

In all patients, the primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS). Secondary endpoints were objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), overall survival (OS), and safety. PFS encompassed the time from the first day of apatinib to documented progression or death. Objective tumor responses included complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). The objective remission rate (ORR) was calculated based on CR + PR. The disease control rate (DCR) was calculated based on CR + PR + SD. OS was defined as the time from the first day of apatinib treatment to death or last follow-up. The follow-up continued until March 2020.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the proportions of patients achieving responses and assessed 95% CIs using the Clopper–Pearson method, and the median duration of response and overall survival, and associated 95% CIs with the Kaplan–Meier method. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0.

Results

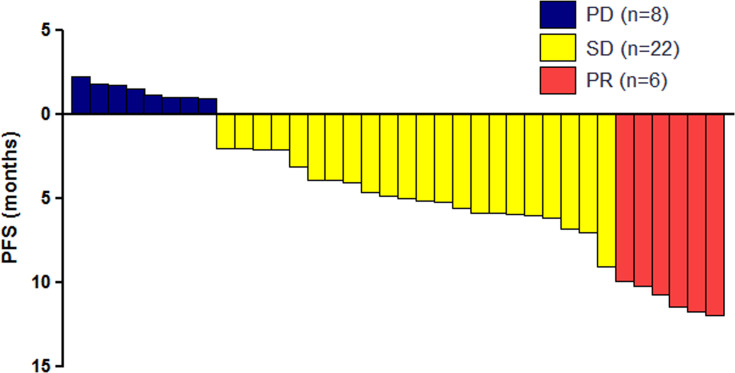

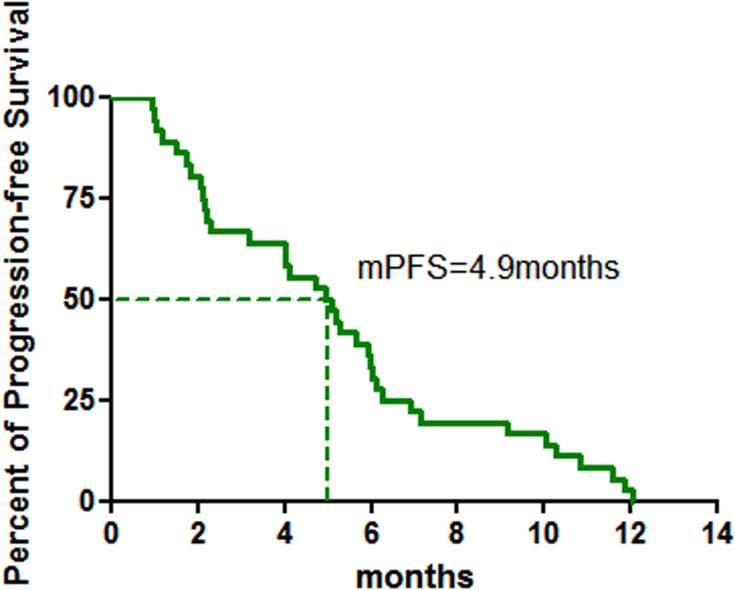

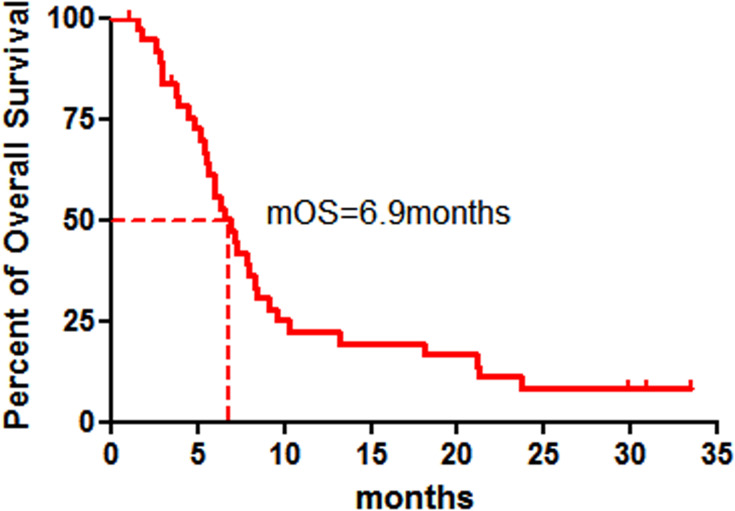

A total of 38 patients were enrolled in the study between June 11, 2015 and August 29, 2018 (Table 1): 97.4% male, 76.3% current/former smokers and 50.0% with ECOG 2–3 performance status. Most patients had received 1 (50.0%) or ≥2 (39.5%) prior lines of therapy. Two patients failed to evaluate efficacy for refusing CT examination, so that 36 patients were eligible for evaluation of tumor response to apatinib (Table 2). After apatinib monotherapy, partial response (PR) was achieved in six patients, stable disease (SD) in 22 patients, and progression disease (PD) in eight patients. The objective remission rate (ORR) was 16.7% (6/36) and the total disease control rate (DCR) was up to 77.8% (28/36). The median PFS of apatinib was 4.9 months (95% CI: 3.3–6.5 months) (Figures 1 and 2). The longest PFS was 360 days in a patient (250 mg/d dosage). Followed up to March 2020, 35 of 38 patients were dead, and the one-year survival rate was 21.1% (8/38). The median OS of apatinib was 6.9 months (95% CI: 5.2–8.5 months) (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean ± SD | (67.5 ± 6.9) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 37 | 97.4% |

| Female | 1 | 2.6% |

| Smoke history | ||

| Yes | 29 | 76.3% |

| No | 9 | 23.7% |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 3 | 7.9% |

| 1 | 16 | 42.1% |

| 2 | 16 | 42.1% |

| 3 | 3 | 7.9% |

| Stage | ||

| IIIA | 1 | 2.6% |

| IIIB | 7 | 18.4% |

| IIIC | 7 | 18.4% |

| IV | 23 | 60.5% |

| Number of prior regimens | ||

| 0 | 4 | 10.5% |

| 1 | 19 | 50.0% |

| ≥2 | 15 | 39.5% |

Table 2.

Treatment Responses

| Evaluation | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| CR | 0 | 0 |

| PR | 6 | 16.7% |

| SD | 22 | 61.1% |

| PD | 8 | 22.2% |

Figure 1.

Waterfall plot for the progression-free survival (PFS) of the 36 patients enrolled in the study. *The columns above the horizontal axis represent the patients who achieved PD (blue), whereas the below represent the patients who achieved PR (red) and SD (yellow).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier graph for the progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with SqCC (n = 36).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier graph for the overall survival (OS) of patients in the study (n = 38).

All patients were assessed for toxicity. The incidence of adverse events (any grade) regardless of causality was 81.6% (31/38). No patients discontinued the study. The adverse effects of apatinib treatment included hypertension (16/38, 42.1%), proteinuria (9/38, 23.7%), hand-foot reaction (8/38, 21.1%), hemoptysis (7/38, 18.4%), fatigue (19/38, 50.0%), neutropenia (2/38, 5.3%), oral mucositis (4/38, 10.5%), heart dysfunction (1/38, 2.6%), abnormal liver function (1/38, 2.6%), thrombocytopenia (1/38, 2.6%) and loss of appetite (9/38, 23.7%; Table 3). Most adverse effects were from Grade 1 to Grade 2, which were tolerable and manageable. No grade 4 adverse effect or drug-related mortality occurred.

Table 3.

Possible Treatment-Related Adverse Events

| I–II | III | IV | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-hematological | ||||

| Hypertension | 10 (26.3%) | 6 (15.8%) | 0 | 16 (42.1%) |

| Proteinuria | 7 (18.4%) | 2 (5.3%) | 0 | 9 (23.7%) |

| Hand-foot reaction | 8 (21.1%) | 0 | 0 | 8 (21.1%) |

| Oral mucositis | 4 (10.5%) | 0 | 0 | 4 (10.5%) |

| Fatigue | 15 (39.5%) | 4 (10.5%) | 0 | 19 (50.0%) |

| Loss of appetite | 7 (18.4%) | 2 (5.3%) | 0 | 9 (23.7%) |

| Hemoptysis | 7 (18.4%) | 0 | 0 | 7 (18.4%) |

| Heart dysfunction | 0 | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (2.6%) |

| Abnormal liver function | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.6%) |

| Hematological | ||||

| Neutropenia | 2 (5.3%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.3%) |

| thrombocytopenia | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.6%) |

Dose reductions occurred in 5 (13.2%) of 38 patients, of whom 3 (60%) patients required only one dose reduction, and 2 (40%) patients had two dose reductions. Three (60%) of the five patients had the first dose reduction for apatinib at the completion of the first cycle, and the occurrence of the first dose reduction for apatinib was recorded in two (40%) patients during the second cycle.

Discussion

To our knowledge, up to date, there remains no randomized controlled trial focused on apatinib monotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Our study reported, for the first time, the efficacy and safety of apatinib at a low-dosage of 250 or 125 mg daily in patients with platinum-refractory or chemotherapy rejected advanced lung squamous-cell carcinoma. We found that the ORR and DCR were 16.7% and 77.8%, and the median PFS and OS were 4.9 and 6.9 months, respectively. Furthermore, most adverse effects were tolerable and manageable.

As an oral anti-angiogenesis drug, apatinib selectively inhibited VEGFR-2 activation. Apatinib was beneficial to increase survival rate as compared with placebo in chemotherapy-refractory advanced gastric cancer patients in a Phase III trial (6.5 vs 4.7 months, P = 0.0149).13 Apatinib was also reported to be effective for the treatment of metastatic breast carcinoma patients who failed standard treatment (PFS 3.3 months, OS 10.7 months).14 In another study of salvage treatment with apatinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer, DCR and ORR were 61.9% and 9.5%, respectively.15 The values of DCR and ORR in the present investigation were 77.8% and 16.7%, correspondingly, which indicates superior efficacy over docetaxel as second-line chemotherapy in NSCLC.17 Of note, half of the patients in the present examination had PS ≥ 2, which might have an influence on the efficacy of apatinib.

The addition of bevacizumab, a representative for anti-angiogenesis drugs, to chemotherapy was beneficial to OS in advanced nonsquamous NSCLC.8 However, it has not been approved for the treatment of squamous-cell carcinoma due to severe hemoptysis.10,11 Lung SqCC has been a restricted area for anti-angiogenic drugs for a long time. Until 2014, the subgroup analysis in the REVEL study had shown that patients with SqCC seemed to have derived similar benefit from treatment with ramucirumab plus docetaxel without an increase in toxicity, particularly respiratory tract hemorrhage, when compared with the placebo group and non-squamous disease group.9 The reason that the authors concluded might be that bevacizumab was a monoclonal antibody against VEGF and ramucirumab especially against VEGFR2, which localized to tumor blood vessels.

The combination of ramucirumab and docetaxel had more pronounced beneficial effects than simple chemotherapy in the REVEL study (4.5 vs 3.0 months, P < 0.01).9 Few investigations have been focused on the efficiency of anti-angiogenic drugs as monotherapy in advanced lung SqCC. Two clinical cases were reported of NSCLC patients treated with apatinib, with PFS of 4.6 and 6 months.18 Another study found that the median PFS for advanced NSCLC patients by using oral apatinib alone as post-second-line therapy was 4.4 months. In our investigation, the use of apatinib as monotherapy in advanced lung SqCC patients contributed to achieving a median 4.9-month PFS. Previous evidence showed that apatinib exerted its anti-cancer effect not only via cytotoxicity but also via inhibition of migration and invasion by suppressing the RET/Src signaling pathway.19 However, further research on the precise mechanism of action in lung cancer is still required.

Several findings of our study are different from those of previous ones. First, all our patients were with lung SqCC, rather than non–small-cell lung cancer. Thus, our results would be more convincing for the usage of apatinib in advanced lung SqCC treatment. Second, we used apatinib at an initial dose of 250 mg/d, lower than the amount of apatinib applied in previous clinical trials. Zeng et al reported the efficacy of apatinib (250–425 mg/d) in SCC patients with a median PFS of 3.1 months,20 which was significantly less than PFS of our patients. As seen from the results, our patients achieved a median 4.9-month PFS and suffered less adverse effects. Interestingly, in the study of Hu et al,14 where the recommended dose was 500 mg daily, the rate of grade 3/4 toxicity was significantly decreased, but the efficacy was similar to that of the daily regimen of 850 mg in breast carcinoma. Therefore, we suggested that the dosage of apatinib had little effect on its efficacy but was related to the severity of side effects. Further investigation remains to be done to confirm the most suitable dosage of apatinib in patients with lung SqCC. Third, our study reported the median OS simultaneously, which might be a more valuable endpoint than PFS.

The toxicity profile was basically similar to that reported in earlier clinical trials,12–14 including hypertension, proteinuria, hand-foot skin reaction, hematological toxicities, fatigue, etc., most of which were grade 1 and 2. A phase III clinical trial showed that anti-angiogenesis side effects, such as hypertension, proteinuria and hand-foot syndrome, often indicated better clinical efficacy among patients with gastric cancer administered with apatinib.13 A retrospective cohort study of 269 patients with gastric cancer receiving apatinib in two phase III clinical trials further demonstrated that patients with side effects including hypertension, proteinuria, and hand-foot syndrome had a longer overall survival, progression-free survival, and disease remission rate.21 Therefore, these adverse reactions can be used as a basis for the establishment of a prognostic scoring system to predict the efficacy of apatinib. In our study, all six patients achieved PR had one of the three side effects, and none of the patients achieved PD had the above side effects.

However, there are several limitations to our study. First, 38 patients were included in our study, and the efficacy of the treatment could be evaluated in only 36 patients. The results of a larger-scale multicenter study would be more convincing. Second, the patients were treated with apatinib as first to fifth-line therapy based on their different status and willingness. Moreover, herein, we conducted a single-arm, phase II prospective cohort study, not a randomized controlled trail, which would have produced more persuasive results. A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial needs to be conducted to further validate the efficiency and safety of apatinib in the treatment of lung SqCC patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study indicated that apatinib might be a therapeutic option in advanced lung squamous-cell carcinoma patients and confirmed that anti-angiogenic therapy is feasible in lung squamous-cell carcinoma. However, further elucidation is needed for the determination of the optimal dosage, patients, and number of treatment lines.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Research Fund from Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology-Hengrui (Grant No. Y-HR2015-034), the Research Fund from Jiangsu Health and Family Planning Commission (Grant No. Z201615), and the Research Fund from Changzhou Health and Family Planning Commission (Grant No. ZD201711), the Young Scientists Foundation of Changzhou No.2 People’s Hospital (Grant No. 2018K004), the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81874230), Jiangsu Social Development Project (Grant No. BE2018726), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grants No. BK20171484), the Project of Invigorating Health Care through Science, Technology, and Education (Grant No. Jiangsu Provincial Medical Youth Talent QNRC2016856) and the Summit of the Six Top Talents Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. 2017-WSN-179).

Abbreviations

Squamous-cell carcinoma (SqCC); non-small cell carcinoma (NSCLC); Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2); tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI); progression-free survival (PFS); objective response rate (ORR); disease control rate (DCR); overall survival (OS); complete response (CR); partial response (PR); stable disease (SD); progressive disease (PD).

Data Sharing Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author Hua Jiang upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Changzhou No.2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. All participants provided written informed consent and the procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The abstract of this paper was presented at the WCLC Conference with the name “Efficacy of low-dosage apatinib monotherapy in treatment of advanced lung squamous cell carcinoma as a poster presentation with interim findings” and was published in “ASCO Abstracts” in JCO Journal with the name “Efficacy and safety of low-dosage apatinib monotherapy in advanced lung squamous cell carcinoma” (DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.e21170).

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dela Cruz C, Tanoue L, Matthay R. Lung cancer: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32:605–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li T, Kung HJ, Mack PC, Gandara DR. Genotyping and genomic profiling of non-small cell-lung cancer: implications for current and future therapies. J Chin Oncol. 2013;31:1039–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itsudomi T. Advances in target therapy for lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:101–106. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hicklin DJ, Ellis LM. Role of the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1011–1027. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen LS. VEGF-targeted therapy: therapeutic potential and recent advances. Oncologist. 2005;10(6):382–391. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-6-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falcon BL, Chintharlapalli S, Uhlik MT, Pytowski B. Antagonist antibodies to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) as anti-angiogenic agents. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;164:204–225. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxelcarboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garon EB, Ciuleanu TE, Arrieta O, et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second-line treatment of stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy (REVEL): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised Phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384:665–673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60845-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson DH, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny WF, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2184–2191. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandler AB, Schiller JH, Gray R, et al. Retrospective evaluation of the clinical and radiographic risk factors associated with severe pulmonary hemorrhage in first-line advanced, unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel plus bevacizumab. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1405–1412. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Qin S, Xu J, et al. Apatinib for chemotherapy-refractory advanced metastatic gastric cancer: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3219–3225. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.8585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Qin S, Xu J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1448–1454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu X, Zhang J, Xu B, et al. Multicenter phase II study of apatinib, a novel VEGFR inhibitor in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1961–1969. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song ZB, Yu XM, Lou GY, Shi X, Zhang YP. Salvage treatment with apatinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:1821–1825. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S113435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng DX, Wang CG, Lei W, Huang JA, Jiang JH. Efficiency of low dosage apatinib in post-first-line treatment of advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(39):66248–66253. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(10):2095–2103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding L, Li QJ, You KY, Jiang ZM, Yao HR. The use of apatinib in treating nonsmall-cell lung cancer: case report and review of literature. Medicine. 2016;95(20):e3598. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin C, Wang S, Xie W, Zheng R, Gan Y, Chang J. Apatinib inhibits cellular invasion and migration by fusion kinase KIF5B-RET via suppressing RET/Src signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2016;7:59236–59244. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng DX, Lei W, Wang CG, Huang JA, Jiang JH. Low dosage of apatinib monotherapy as rescue treatment in advanced lung squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;83:439–442. doi: 10.1007/s00280-018-3743-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Qin S, Wang Z, et al. Early presence of anti-angiogenesis-related adverse events as a potential biomarker of antitumor efficacy in metastatic gastric cancer patients treated with apatinib: a cohort study. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0521-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]