Abstract

CPAP is an essential component for centriole formation. Here, we report that CPAP is also critical for symmetric spindle pole formation during mitosis. We observed that pericentriolar material between the mitotic spindle poles were asymmetrically distributed in CPAP-depleted cells even with intact numbers of centrioles. The length of procentrioles was slightly reduced by CPAP depletion, but the length of mother centrioles was not affected. Surprisingly, the young mother centrioles of the CPAP-depleted cells are not fully matured, as evidenced by the absence of distal and subdistal appendage proteins. We propose that the selective absence of centriolar appendages at the young mother centrioles may be responsible for asymmetric spindle pole formation in CPAP-depleted cells. Our results suggest that the neural stem cells with CPAP mutations might form asymmetric spindle poles, which results in premature initiation of differentiation.

Keywords: Spindle pole, CPAP, Centriole maturation, Asymmetric cell division

1. Introduction

The centrosome is a major microtubule-organizing center that consists of a pair of centrioles surrounded by pericentriolar material (PCM). Centrioles duplicate and segregate in tight association with the cell cycle. Procentrioles begin to form next to mother centrioles at the G1/S phase. The procentrioles are elongated, and they eventually disengage from the mother centriole at the end of mitosis. Centriole disengagement is considered important for licensing a new round of centriole duplication [1]. The disengaged centriole becomes a mother centriole when a new procentriole is formed next to it. However, this young mother centriole is still structurally immature. For example, the young mother centriole lacks distal and subdistal appendages until the cell undergoes mitosis [2]. Therefore, it takes one and a half cell cycles for a procentriole to become a fully matured mother centriole.

Genetic analysis in Caenorhabditis elegans identified a number of centriolar proteins that are involved in centriole assembly, such as ZYG-1, a protein kinase, and SAS-4, SAS-5, SAS-6 and SPD-2, which contain coiled-coil domains [3,4]. During centriole biogenesis, these proteins are sequentially recruited to centrioles [5,6]. ZYG-1 recruits SAS-5 and SAS-6, which are required to SAS-4 incorporation [6,7]. It is proposed that the centriole duplication mechanism is evolutionally conserved from C. elegans to human [8]. CPAP, the human homolog of SAS-4, is essential for centriole formation in human cells [9–12].

Primary microcephaly is a rare, recessive genetic disease in which the prenatal brain growth is significantly reduced while the brain structure is left intact [13]. CPAP is one of the causal genes implicated in primary microcephaly [14]. However, it is not understood how the neural cell number is reduced in individuals with CPAP mutations. In this study, we revealed that CPAP depletion results in the asymmetry of spindle pole activity, which probably results in the premature initiation of asymmetric cell division.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Antibodies

We generated antibodies against CPAP [9], CEP135 [15], CP110 [9], pericentrin [16], centrin-2 [17], CEP215 [18] and cenexin1 [19]. Antibodies against γ-tubulin (GTU-88, Sigma or C-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and CENP-B (H-65, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were purchased.

2.2. Cell culture and cell cycle synchronization

HeLa cells were grown at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Mitotic HeLa cells were enriched with the double-thymidine block and release. In the rescue experiments, the cells were arrested at S phase with a single thymidine block and release followed by MG132 treatment.

2.3. Transfection and RNA interference

siCPAP (GGA CUG ACC UUG AAG AGA ATT), siCTL (scrambled sequence for control) (GCA AUC GAA GCU CGG CUA CTT), sicenexin1 (AGA CUA AUG GAG CAA CAA G) were used for RNAi experiments. The siRNAs were transfected into HeLa cells using RNAi MAX reagents (Invitrogen). Plasmids were transfected with FuGENE HD (Roche). For rescue experiments, siRNAs and DNAs were sequentially transfected.

2.4. Immunoblot analysis

HeLa cells were lysed in the sample buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mM dithiothreitol, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol). Samples were loaded in 8% polyacrylamide gels and then transferred into nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk in TBST (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.3% Triton X-100) for 30 min, incubated with anti-CPAP (1:100), anti-β-tubulin (1:1000) antibodies for 3 h at room temperature. After washing three times with TBST for 5 min, the membranes were incubated with mouse and rabbit secondary antibodies (1:10,000) for 30 min. After the membranes were washed three times with TBST for 5 min, the peroxidase activity was detected using ECL solutions.

2.5. Immunofluorescence and microscopy

For indirect immunocytochemistry, HeLa cells were grown on 12-mm coverslips and fixed with cold 100% methanol for 10 min. The cells were then permeabilized and blocked with 3% BSA in 0.5% PBST for 15 min. Primary antibodies were diluted in 3% BSA in 0.5% PBST, incubated at room temperature for 1 or 2 h and coverslips were washed three times in 0.1% PBST. Secondary antibodies were diluted in 3% BSA in 0.5% PBST, incubated for 30 min at room temperature and washed again three times in 0.1% PBST. For DNA staining, DAPI solution was used at the final step for 4 min. The coverslips were mounted on slides and observed with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX51) equipped with a CCD camera (Qicam fast 1394, Qimaging). Images were processed using ImagePro 5.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc.) and statistic analyzed with Sigma Plot (Systat Software, Inc.).

To measure the length of centrioles, we used a super-resolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM; Nikon N-SIM) equipped with a CFI Apo TIRF 100× oil objective lens (NA1.49) and iXon DU-897 EMCCD camera. The images were taken as Z-stack with distance between planes of 0.1 μm. The center of the signal was determined by intensity profile in NIS-Elements software. The antibodies were conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555 dyes (Molecular Probes).

3. Results

3.1. Asymmetric spindle pole formation in CPAP-depleted cells

To begin our study for mitotic functions of CPAP, we depleted the endogenous CPAP with siRNA transfection. Transfection of a CPAP-specific siRNA (siCPAP) efficiently reduced cellular CPAP levels within 48 h (Fig. 1A). We examined the mitotic progression of CPAP-depleted cells. The phase-contrast microscopic observations revealed that the mitotic index in the CPAP-depleted population increased by 1.5-fold more than that of the control population (Fig. 1B). As reported previously, the number of centrioles was reduced and abnormal spindle formation was accompanied in the CPAP-depleted cells (data not shown) [20]. However, bipolar spindles with intact numbers of centrioles were also observed as a mild phenotype of CPAP depletion. In this work, we investigated mild phenotypes of CPAP depletion during mitosis.

Fig. 1.

Asymmetric spindle poles in CPAP-depleted mitotic cells. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with the control (siCTL) or CPAP (siCPAP) siRNAs and cultured for 48 h. The cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the CPAP and β-tubulin antibodies. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with control (siCTL) or CPAP (siCPAP) siRNAs. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were observed with a phase-contrast microscope. The scale bar represents 100 μm. The mitotic index was determined with more than 3000 cells per experimental group from three independent experiments. The results were presented as means and standard errors *P < 0.05. (C) The CPAP-depleted HeLa cells were coimmunostained with the CPAP (green) and γ-tubulin (red) antibodies. The scale bar represents 10 μm. The relative γ-tubulin intensity between a pair of spindle poles was determined. A difference in intensity greater than 1.5 was defined as an asymmetric distribution. Over 300 cells per group were analyzed from three independent experiments, and the results are presented as means and standard errors. (D) The CPAP-depleted mitotic cells were immunostained with the centrin-2 antibody along with the pericentrin or CEP215 antibody. The scale bar represents 10 μm. Relative intensities of pericentrin and CEP215 were measured in spindle pole pairs with an intact number of centrioles. A difference in intensity greater than 1.5 was defined as an asymmetric distribution. For statistical analysis, over 180 mitotic cells per group were analyzed from two independent experiments. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

When we immunostained the CPAP-depleted cells with a γ-tubulin antibody, we repeatedly observed that the γ-tubulin intensities in a spindle pole pair were significantly different to each other (Fig. 1C). We quantified asymmetry of the spindle pole pair by counting the number of cells in which the γ-tubulin intensity difference between the spindle pole pair was larger than 1.5-fold. The results showed that more than 50% of the CPAP-depleted cells had asymmetric spindle poles, whereas less than 10% of the control cells displayed asymmetric spindle poles (Fig. 1C). We examined the asymmetric distribution of other PCM proteins between the spindle pole pair of CPAP-depleted cells. To avoid any complication, we examined only the spindle pole pairs with an intact number of centrioles. The results showed a significant increase of spindle pole pairs with asymmetric distribution of pericentrin and CEP215 in the CPAP-depleted cells (Fig. 1D). These observations suggest that PCM is asymmetrically distributed between the spindle pole pair of CPAP-depleted cells.

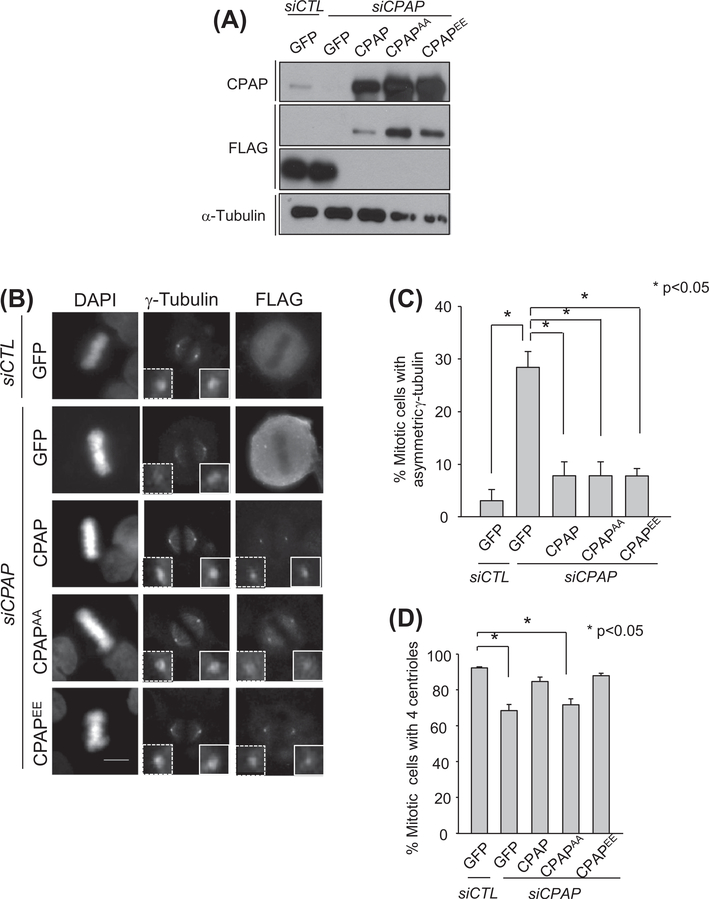

We performed rescue experiments with ectopic Flag-CPAP proteins to confirm the importance of CPAP in spindle pole symmetry. The immunoblot analysis revealed that a sufficient amount of the ectopic Flag-CPAP was expressed in the CPAP-depleted cells (Fig. 2A). Flag-CPAP was properly localized at the spindle poles (Fig. 2B). At the same time, the wild type Flag-CPAP significantly reduced the number of CPAP-depleted mitotic cells with asymmetric spindle poles (Fig. 2C). The spindle pole asymmetry was also rescued with both Flag-CPAPAA and Flag-CPAPEE in which point mutations were introduced into the PLK2 phosphorylation sites S589 and S595 to become alanines and glutamates, respectively (Fig. 2C in [9]). We counted the number of centrioles in the same experimental groups. Both wild-type Flag-CPAP and Flag-CPAPEE rescued the number of centrioles to the control level (Fig. 2D). However, as reported previously, the centriole duplication activity was not rescued with Flag-CPAPAA (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that spindle pole asymmetry in CPAP-depleted mitotic cells is independent of CPAP function for procentriole assembly.

Fig. 2.

Rescue experiments with ectopic FLAG-CPAP proteins. (A) The CPAP-depleted HeLa cells were transfected with the FLAG-tagged expression vectors (pFLAG-GFP, pFLAG-CPAP, pFLAG-CPAPAA and pFLAG-CPAPEE). Expression of the endogenous and ectopic CPAP proteins was confirmed with the immunoblot analysis. (B) The CPAP-rescued cells were enriched at mitotic phase with a thymidine block and release, followed by the MG132 treatment for 1 h. The cells were immunostained with antibodies specific for FLAG and γ-tubulin. The scale bar represents 10 μm. (C) The mitotic cells with asymmetric distribution of γ-tubulin were determined by comparing relative γ-tubulin intensities between the spindle pole pair. More than 300 cells per group were analyzed from four independent experiments, and the results are presented as means and standard errors *P < 0.05. (D) The CPAP-rescued cells were immunostained with the antibodies specific to FLAG and centrin-2 to determine the centriole number at the mitotic spindle poles. For statistical analysis, more than 200 mitotic cells per group were analyzed from three independent experiments.

3.2. Centriole lengths in CPAP-depleted cells

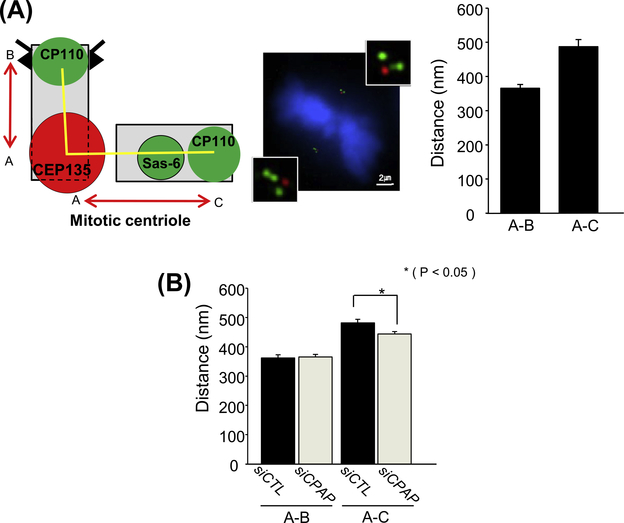

C. elegans SAS-4 is essential for centriole elongation as sas-4 mutants include variable sizes of centrioles [10]. Ectopic expression of human CPAP lengthens centrioles, suggesting that CPAP is also involved in centriole elongation [10–12]. To test whether centriole length determines PCM asymmetry of CPAP-depleted cells or not, we examined the centriole size using a super-resolution microscope. Metaphase centrioles of control HeLa cells were immunostained with the CEP135 and CP110 antibodies as proximal and distal end markers, respectively, and the distance between two markers were determined. SAS6 was also immunostained to distinguish the procentriole from the mother centriole. Average distance of the CEP135 and CP110 signals in mother and procentriole were 360 and 480 nm, respectively (Fig. 3A). These numbers are smaller than actual length of mother (513 nm) and daughter (400 nm) centrioles as determined by electron microscopes [21]. We reasoned that the distance between the centers of the distal and proximal markers should be smaller than actual size of the centriole. With the same reason, the distance between CEP135 and procentriolar CP110 should be larger, due to the intercentriole gap and the CEP135 signaling center toward the mother centriole (Fig. 3A) [22].

Fig. 3.

Determination of centriole lengths in CPAP-depleted mitotic cells. (A) Mitotic HeLa cells were coimmunostained with antibodies specific to CEP135 (red), CP110 (green) and SAS-6 (green), and the spindle poles were observed with a super-resolution microscope. Distance between red (CEP135) and green (CP110) dots were determined. Procentrioles were identified with two consecutive green dots. Nineteen centrioles were analyzed and the data were presented as means and standard errors. (B) The distance between CEP135 (red) and CP110 (green) signals was determined in CPAP-depleted mitotic cells. Over 60 centrioles per group were analyzed in three independent experiments *P < 0.05. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We compared the distance between CEP135 and CP110 signals of CPAP-depleted cells with that of the control cells. The results showed that the sizes of mother centrioles in CPAP-depleted mitotic cells are identical to those of the control cells (Fig. 3B). The distance in procentrioles was slightly smaller in the CPAP-depleted cells (Fig. 3B). However, we do not observe any difference in centriole sizes between a pair of spindle poles within a cell (data not shown). These results suggest that asymmetry in the bipolar spindles of CPAP-depleted mitotic cells are not stemmed from the difference in centriole sizes. Our results with HeLa cells are in contrast with the sas-4 mutants in which the amount of PCM is proportionally reduced with respect to the centriole length [24].

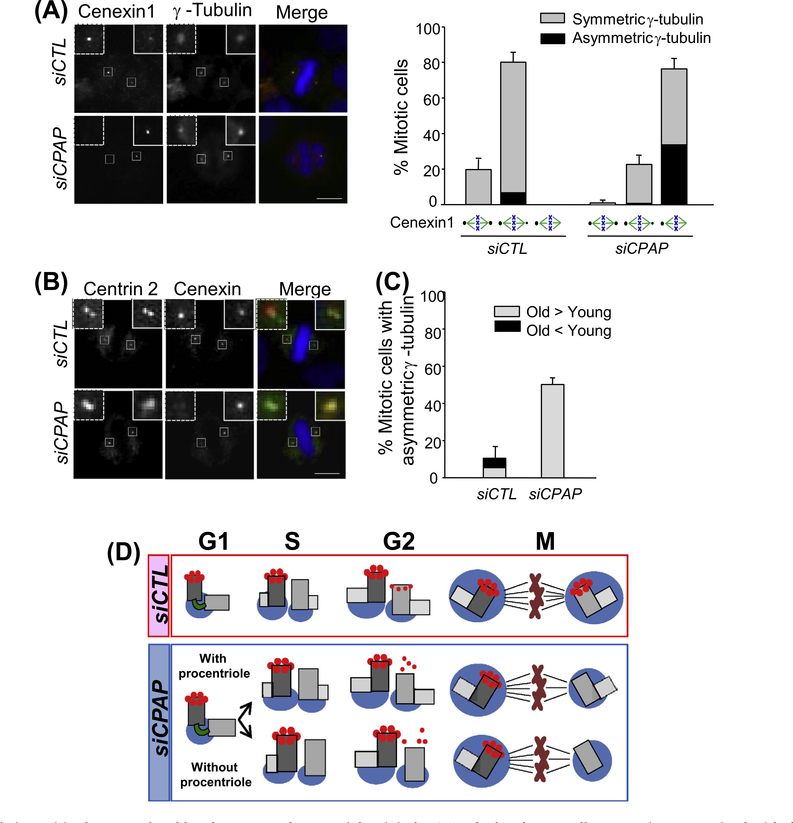

3.3. Centriole maturation defects in CPAP-depleted cells

A daughter centriole is disengaged from its mother centriole at the end of mitosis and becomes a young mother centriole once a nascent procentriole is formed next to it at the G1/S phase. However, the young mother centriole is structurally immature until the end of the cell cycle. For example, the young mother centriole initially lacks distal and subdistal appendages. Cenexin1 is a subdistal appendage protein at the mother centriole [19]. It is known that the young mother centriole still has a weak cenexin1 signal even during the M phase [19]. In fact, we observed that more than 80% of the control cells had an unequal cenexin1 signal distribution in their spindle poles (Fig. 4A). Most of the CPAP-depleted cells also had uneven cenexin1 signal distribution in their spindle pole pairs but the signal intensities at the young mother centriole were much weaker or hardly detectable (Fig. 4A). This suggests that maturation of the young mother centriole is significantly delayed in CPAP-depleted cells. An uneven distribution of γ-tubulin was observed in the spindle poles with immature young mother centrioles (Fig. 4A). It is of note that even the spindle poles with no cenexin1 signal include the centriole pairs (Fig. 4B). Importantly, weaker γ-tubulin signals were exclusively detected at the spindle poles of no cenexin1 signal in CPAP-depleted cells (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that the spindle pole with old mother centriole includes more PCM than that with young mother centriole in an asymmetric spindle pole pair of CPAP-depleted cells.

Fig. 4.

Relative spindle pole intensities between the old and young mother centrioles. (A) The CPAP-depleted HeLa cells were coimmunostained with the cenexin1 (green) and γ-tubulin (red) antibodies. The cenexin1 staining patterns at the spindle poles were categorized into equal pair, unequal pair and a single dot. Asymmetric γ-tubulin signal (black bar) was also determined within the experimental groups. Over 300 cells per group were analyzed from three independent experiments, and the results are presented as means and standard errors. (B) The CPAP-depleted cells were coimmunostained with antibodies specific to centrin-2 (green) and cenexin (red). DNA was stained with DAPI and merged with the immunostained images. The scale bar represents 10 μm. (C) The CPAP-depleted cells were coimmunostained with the cenexin1 and γ-tubulin antibodies. Gray and black bars indicate the cells with a strong γ-tubulin signal at the spindle poles with old and young mother centrioles, respectively. Over 300 cells per group were analyzed from three independent experiments. (D) Model Depletion of CPAP may result in defects in centriole duplication. In addition, the young mother centriole in CPAP-depleted cells is still immature even in the M phase, irrespective of the presence of procentriole. The immaturity of young mother centriole results in the absence of distal and subdistal appendages in the young mother centriole, which may cause an asymmetric spindle pole in CPAP-depleted cells. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated CPAP functions in bipolar spindle formation during mitosis. Prolonged depletion of CPAP resulted in centriole loss and monopolar spindle formation [20,24]. At the same time, asymmetry was observed even in bipolar spindle poles with intact number of centrioles. C. elegans SAS-4 is also known to be critical for spindle pole formation as well as for centriole duplication. The sas-4 mutants contain small centrioles, and the amount of PCM is proportionally reduced with respect to the centriole length [23]. In HeLa cells, the mother centriole lengths in CPAP-depleted cells are more or less identical to those of control cells. Therefore, the spindle pole asymmetry is not likely due to the size difference of mother centrioles in CPAP-depleted cells. Rather, we propose that the mother centrioles are not fully matured in the CPAP-depleted cells and, as a result, the microtubule organizing activity of the spindle pole with an immature mother centriole is not sufficiently extended (Fig. 4D). We believe that spindle pole asymmetry in CPAP-depleted cells is independent of procentriole assembly, because the PLK2 phosphorylation-resistant CPAP mutant did not rescue the centriole duplication activity but did rescue the phenotype of asymmetric spindle pole formation (Fig. 2D).

This is the first report that CPAP is required for mother centriole maturation in mammalian cells, as evidenced by the absence of distal and subdistal appendage proteins in CPAP-depleted cells. The distal and subdistal appendages are believed to have roles in microtubule anchorage and in primary cilia formation [25–27]. The selective absence of centriolar appendages at the young mother centrioles may be responsible for asymmetric spindle pole formation in CPAP-depleted cells (Fig. 4D). It remains to be determined whether CPAP directly participates in appendage formation or not. It was reported that Drosophila SAS-4 scaffolds the preassembled cytoplasmic complexes of PCM and tethers them to the centrosome [28,29]. Therefore, it is possible that CPAP is indirectly involved in the appendage formation by recruiting PCM components which are essential for appendage formation in the young mother centriole.

Many stem cells divide symmetrically to increase their own population and subsequently initiate asymmetric division to produce differentiated cells. Switching from symmetric to asymmetric division should be a tightly controlled process for the production of differentiated cells from stem cells at the right moment. Centriole maturation is considered an important factor for stem cell differentiation as shown in a report that ninein knockdown results in the premature depletion of progenitors during cortex development in mice [30]. Here, we observed that the spindle poles in CPAP-depleted cells become asymmetric and the young mother centrioles in CPAP-depleted cells are structurally immature even until mitosis. Our results predict that neural stem cells in CPAP mutant individuals might prematurely initiate asymmetric division, which causes a reduction in the stem cell population and subsequent reduction of the differentiated cell population. Our results suggest that defects in mother centriole maturation may be a reason why microcephaly is derived from CPAP mutations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the BioImaging Research Center at GIST; the Basic Research Program (2012R1A2 A201003512); the Science Research Center Program (Grant No. 2011-0006425) of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. M. Lee is supported by the BK-Plus Project.

Abbreviation:

- PCM

pericentriolar material

References

- [1].Tsou MF, Stearns T, Mechanism limiting centrosome duplication to once per cell cycle, Nature 442 (2006) 947–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Loncarek J, Khodjakov A, Ab ovo or de novo? Mechanisms of Centriole Duplication, Mol. Cells 27 (2009) 135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Leidel S, Gönczy P, SAS-4 is essential for centrosome duplication in C. elegans and is recruited to daughter centrioles once per cell cycle, Dev. Cell 4 (2003) 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].O’Connell KF, Caron C, Kopish KR, Hurd DD, Kemphues KJ, Li Y, White JG, The C. elegans zyg-1 gene encodes a regulator of centrosome duplication with distinct maternal and paternal roles in the embryo, Cell 105 (2001) 547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Delattre M, Canard C, Gönczy P, Sequential protein recruitment in C. elegans centriole formation, Curr. Biol. 16 (2006) 1844–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pelletier L, O’Toole E, Schwager A, Hyman AA, Müller-Reichert T, Centriole assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans, Nature 444 (2006) 619–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dammermann A, Muller-Reichert T, Pelletier L, Habermann B, Desai A, Oegema K, Centriole assembly requires both centriolar and pericentriolar material proteins, Dev. Cell 7 (2004) 815–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kleylein-Sohn J, Westendorf J, Le Clech M, Habedanck R, Stierhof YD, Nigg EA, Plk4-induced centriole biogenesis in human cells, Dev. Cell 13 (2007) 190–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chang J, Cizmecioglu O, Hoffmann I, Rhee K, PLK2 phosphorylation is critical for CPAP function in procentriole formation during the centrosome cycle, EMBO J. 29 (2010) 2395–2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kohlmaier G, Loncarek J, Meng X, McEwen BF, Mogensen MM, Spektor A, Dynlacht BD, Khodjakov A, Gönczy P, Overly long centrioles and defective cell division upon excess of the SAS-4-related protein CPAP, Curr. Biol. 19 (2009) 1012–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schmidt TI, Kleylein-Sohn J, Westendorf J, Le Clech M, Lavoie SB, Stierhof YD, Nigg EA, Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110, Curr. Biol. 19 (2009) 1005–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tang CJ, Fu RH, Wu KS, Hsu WB, Tang TK, CPAP is a cell-cycle regulated protein that controls centriole length, Nat. Cell Biol. 11 (2009) 825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Thornton GK, Woods CG, Primary microcephaly: do all roads lead to Rome?, Trends Genet 25 (2009) 501–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bond J, Roberts E, Springell K, Lizarraga SB, Scott S, Higgins J, Hampshire DJ, Morrison EE, Leal GF, Silva EO, Costa SM, Baralle D, Raponi M, Karbani G, Rashid Y, Jafri H, Bennett C, Corry P, Walsh CA, Woods CG, A centrosomal mechanism involving CDK5RAP2 and CENPJ controls brain size, Nat. Genet. 37 (2005) 353–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kim K, Lee S, Chang J, Rhee K, A novel function of CEP135 as a platform protein of C-NAP1 for its centriolar localization, Exp. Cell Res. 314 (2008) 3692–3700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee K, Rhee K, Separase-dependent cleavage of pericentrin B is necessary and sufficient for centriole disengagement during mitosis, Cell Cycle 11 (2012) 2476–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kim S, Kim S, Rhee K, Nek7 is essential for centriole duplication and centrosomal accumulation of pericentriolar material proteins in interphase cells, J. Cell Sci. 124 (2011) 3760–3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lee S, Rhee K, CEP215 is involved in the dynein-dependent accumulation of pericentriolar matrix proteins for spindle pole formation, Cell Cycle 9 (2010) 774–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Soung NK, Kang YH, Kim K, Kamijo K, Yoon H, Seong YS, Kuo YL, Miki T, Kim SR, Kuriyama R, Giam CZ, Ahn CH, Lee KS, Requirement of hCenexin for proper mitotic functions of polo-like kinase 1 at the centrosomes, Mol. Cell. Biol. 26 (2006) 8316–8335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kitagawa D, Kohlmaier G, Keller D, Strnad P, Balestra FR, Flückiger I, Gönczy P, Spindle positioning in human cells relies on proper centriole formation and on the microcephaly proteins CPAP and STIL, J. Cell Sci. 124 (2011) 3884–3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chrétien D, Buendia B, Fuller SD, Karsenti E, Reconstruction of the centrosome cycle from cryoelectron micrographs, J. Struct. Biol. 120 (1997) 117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sonnen KF, Schermelleh L, Leonhardt H, Nigg EA, 3D-structured illumination microscopy provides novel insight into architecture of human centrosome, Biol. Open 1 (2012) 965–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kirkham M, Müller-Reichert T, Oegema K, Grill S, Hyman AA, SAS-4 is a C. elegans centriolar protein that controls centrosome size, Cell 112 (2003) 575–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tang CJ, Lin SY, Hsu WB, Lin YN, Wu CT, Lin YC, Chang CW, Wu KS, Tang TK, The human microcephaly protein STIL interacts with CPAP and is required for procentriole formation, EMBO J. 30 (2011) 4790–4804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ibi M, Zou P, Inoko A, Shiromizu T, Matsuyama M, Hayashi Y, Enomoto M, Mori D, Hirotsune S, Kiyono T, Tsukita S, Goto H, Inagaki M, Trichoplein controls microtubule anchoring at the centrosome by binding to Odf2 and ninein, J. Cell Sci. 124 (2011) 857–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ishikawa H, Kubo A, Tsukita S, Tsukita S, Odf2-deficient mother centrioles lack distal/subdistal appendages and the ability to generate primary cilia, Nat. Cell Biol. 7 (2005) 517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mogensen MM, Malik A, Piel M, Bouckson-Castaing V, Bornens M, Microtubule minus-end anchorage at centrosomal and non-centrosomal sites: the role of ninein, J. Cell Sci. 113 (2000) 3013–3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gopalakrishnan J, Mennella V, Blachon S, Zhai B, Smith AH, Megraw TL, Nicastro D, Gygi SP, Agard DA, Avidor-Reiss T, Sas-4 provides a scaffold for cytoplasmic complexes and tethers them in a centrosome, Nat. Commun. 2 (2011) 359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gopalakrishnan J, Chim YC, Ha A, Basiri ML, Lerit DA, Rusan NM, Avidor-Reiss T, Tubulin nucleotide status controls Sas-4-dependent pericentriolar material recruitment, Nat. Cell Biol. 14 (2012) 865–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang X, Tsai JW, Imai JH, Lian WN, Vallee RB, Shi SH, Asymmetric centrosome inheritance maintains neural progenitors in the neocortex, Nature 461 (2009) 947–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]