Abstract

Agents targeting the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) are in clinical development, but, despite some initial success of single agents in sarcoma, response rates are low with brief durations. Thus, it is important to identify markers predictive of response, to understand mechanisms of resistance, and to explore combination therapies. In this study, we found that, although associated with PAX3-FKHR translocation, increased IGF1R level is an independent prognostic marker for worse overall survival, particularly in patients with PAX3-FKHR-positive rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS). IGF1R antibody-resistant RMS cells were generated using an in vivo model. Expression analysis indicated that IGFBP2 is both the most affected gene in the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling pathway and the most significantly downregulated gene in the resistant lines, indicating that there is a strong selection to repress IGFBP2 expression in tumor cells resistant to IGF1R antibody. IGFBP2 is inhibitory to IGF1R phosphorylation and its signaling. Similar to antibodies to IGF1/2 or IGF2, the addition of exogenous IGFBP2 potentiates the activity of IGF1R antibody against the RMS cells, and it reverses the resistance to IGF1R antibody. In contrast to IGF1R, lower expression of IGFBP2 is associated with poorer overall survival, consistent with its inhibitory activity found in this study. Finally, blocking downstream Protein kinase B (AKT) activation with Phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases (PI3K)- or mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-specific inhibitors significantly sensitized the resistant cells to the IGF1R antibody. These findings show that constitutive IGFBP2 downregulation may represent a novel mechanism for acquired resistance to IGF1R therapeutic antibody in vivo and suggest various drug combinations to enhance antibody activity and to overcome resistance.

Keywords: IGF1R, IGFBP2, rhabdomyosarcoma, antibody therapy, drug resistance, drug combination

INTRODUCTION

The insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling pathway are highly conserved and critical for carbohydrate metabolism and glucose control1 and for growth and survival in many organisms.2 The IGF system consists of ligands IGF1 and IGF2, tyrosine kinase receptors, including insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R), IGF2R and two isoforms of the insulin receptor (IR-A and IR-B), and a group of IGF-binding proteins (IGFBP1–6) that may negatively regulate the activities of IGFs.3,4 Although both IGF1 and IGF2 are mainly expressed in the liver in response to growth hormone, their abnormal autocrine or paracrine expression, particularly IGF2, is common in many malignancies.5 Although IGFs mostly work through IGF1R in mediating intracellular signal activation, they are known to activate IR-A, and thus, IRs were suggested to have a role in regulating IGF action and to contribute to the resistance to IGF1R-targeted therapies.6 Both IGF1 and IGF2 bind to IGF1R to activate downstream AKT and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) signaling.7,8 The ligand-mediated phosphorylation of IGF1R leads to the recruitment and phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate IRS-1 and IRS-2, which in turn results in the activation of PI3K and AKT signaling for cell proliferation and survival.3,9

There has been an enormous interest in developing agents that target IGF1R for the clinical management of cancer with dozens of trials on-going.10,11 In some phase I and II studies with single agent IGF1R-targeted antibodies, objective responses were seen against Ewing’s sarcoma.12–14 The IGF1R-targeted agents are safer than anticipated, with limited metabolic toxicity, mainly hyperglycemia. However, there are a number of development issues for IGF1R-targeted antibodies, including their limited efficacy, which is mainly restricted to sarcomas, their low response rates, and their short duration of response of about 7 months.14 Several published phase II and III combination studies failed to provide proof of efficacy.15,16 It is clear that several areas require urgent investigation, including predictive biomarkers, mechanisms of resistance and combination therapies.4,17

Activated IGF1R signaling has been implicated in pediatric sarcomas,18 of which rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common soft tissue tumor in children. IGF2 has been shown to be elevated in RMS and serves as an autocrine signal for growth.19 The more aggressive alveolar RMS is associated with a genomic translocation involving PAX3-FKHR. The PAX3-FKHR fusion oncoprotein is capable of enhancing the expression of a range of genes, including IGF1R.20 Increased AKT signaling is also associated with poor RMS prognosis,21,22 which has been shown to be largely dependent on the activity of IGF1R.23 Some RMS cell lines are highly sensitive to IGF1R antibodies that induce apoptotic cell death.24 Thus, RMS may serve as a good model for the analysis of IGF1R-targeted agents.

In this investigation, we mimic clinical studies with a mouse model in which the IGF1R antibody mediated rapid tumor regression. Tumor growth resumed after 3–4 months of continuous treatment, and two cell lines were made from these resistant tumors. Using expression array analysis, we found that IGFBP2 was both the most commonly downregulated gene and the most affected gene specific to IGF signaling in the resistant cell lines. We followed up on the regulation of IGFBP2 and on its function in regulating IGF1R and associated signaling. Further analysis was performed to establish the association of IGF1R and IGFBP2 expression levels with patient survival. Because it might not be feasible to target IGFBP2, we also analyzed agents targeting pathways downstream of IGF1R for their ability to potentiate IGF1R antibody activity against these resistant cells.

RESULTS

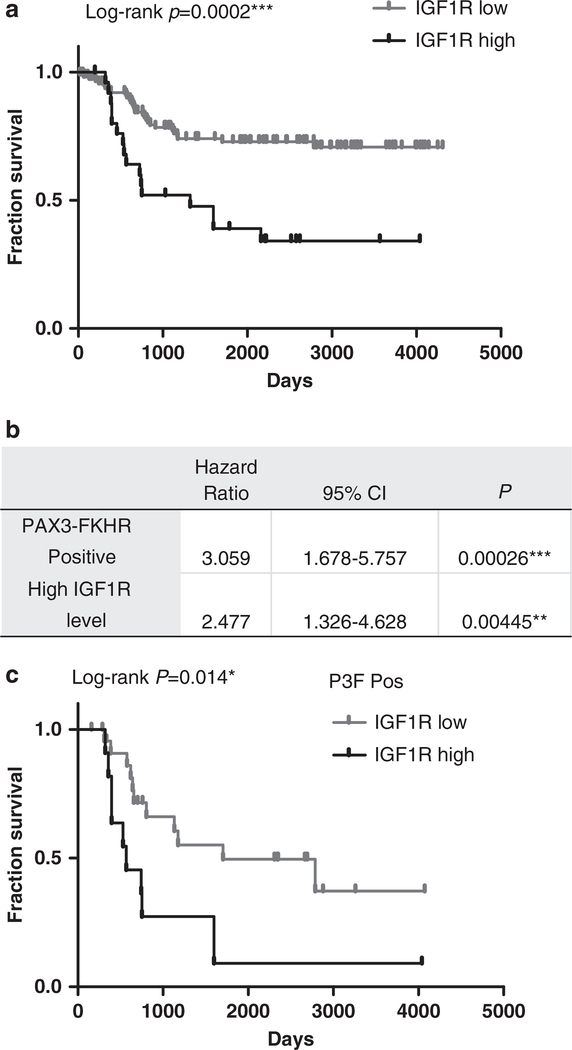

IGF1R is a prognostic biomarker for poor overall survival of RMS patients

To better understand the role of IGF1R in RMS, we examined the association between IGF1R expression and overall survival of patients with RMS using an expression array data set.25,26 For patient partitions, the analysis revealed a clear association (P = 0.0002) between high IGF1R level and poor overall survival in 146 RMS patients (Figure 1a, Supplementary Table S1). Cox-regression analysis reveals that elevated IGF1R expression carries a hazard ratio of 2.477 with 95% confidence interval of 1.326–4.628 (Figure 1b), which is statistically significant (P = 0.0045), indicating that elevated IGF1R is an independent prognostic biomarker for worse overall survival. In comparison, in the same analysis, PAX3-FKHR translocation in RMS patients has a hazard ratio of 3.0588 with P = 0.00026. Interestingly, in patients whose tumors with PAX3-FKHR fusion gene that is an established prognostic biomarker of poor overall survival (n = 35), high IGF1R is associated with worse prognosis (P = 0.014, Figure 1c). Thus, these results suggest that increased IGF1R is a prognostic marker for poor overall survival of RMS patients, and the combination of higher IGF1R expression and PAX3-FKHR predicts the worst survival outcome.

Figure 1.

High IGF1R expression level predicts worse survival in rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) patients. (a) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of 146 RMS patients grouped by IGF1R level (Supplementary Table S1). The cutoff for IGF1R levels was determined using P-value minimization. (b) Cox regression analysis of the RMS patients to determine the hazard ratio of elevated IGF1R on overall survival. (c) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of the effects of IGF1R expression in PAX3-FKHR-positive RMS patients (n = 35). CI, confidence interval. *, significant; **, very significant; ***, extremely significant.

IGFBP2 is the most significantly disregulated gene in IGF1R antibody-resistant Rh41 cells

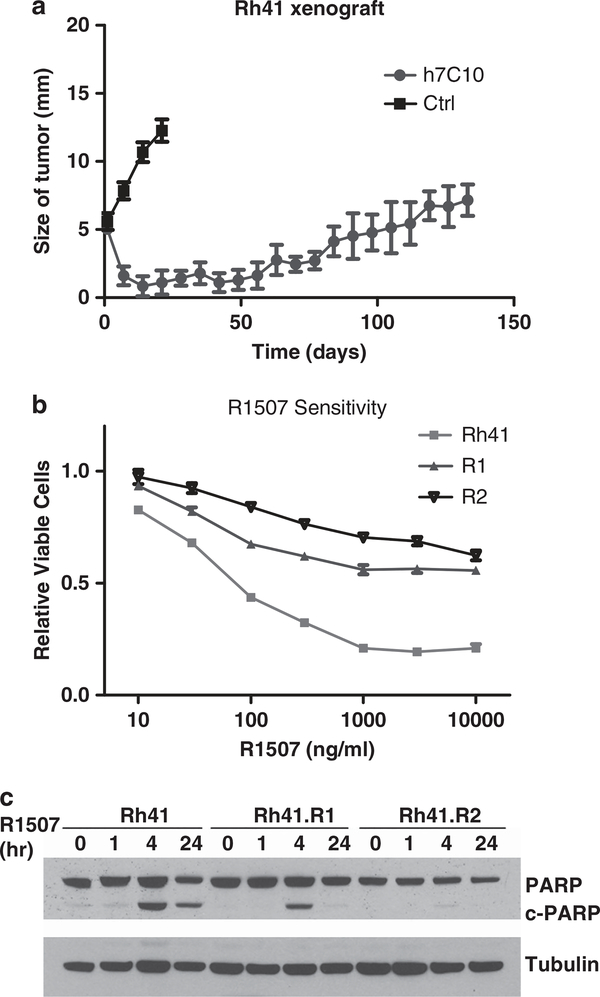

Owing to the difficulty in obtaining human tumor specimens from patients resistant to IGF1R antibody, we sought to model the development of such resistance with intramuscular tumor xenograft mice. Unique aspects of this resistant tumor model system, in comparison with previous studies using drug-resistant cells generated in vitro, are that the in vivo microenvironment may affect drug delivery, tumor response and drug resistance. For instance, a recent study showed that stromal cells secrete hepatocyte growth factor that confers resistance specifically to targeted agents, such as BRAF inhibitors.27 Sensitive RMS Rh41 cells were inoculated intramuscularly into SCID mice. After about 5–6 weeks, when tumors became clearly visible, the mice were treated continuously with h7C10 (MK-0646, Merck) IGF1R antibody once weekly. Although rapid tumor regression was seen initially after treatment, all tumors (n = 10) gradually and invariably became resistant to the antibody (Figure 2a). To explore cellular changes contributing to this resistance, two cell lines, R1 and R2, were derived independently from xenografts of two different mice. Drug sensitivity tests were performed with another IGF1R antibody R1507 (Roche), and the results confirmed their resistance to the antibody treatment (Figure 2b), though R2 was markedly more resistant to R1507 than R1. The analysis of apoptotic marker Poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) cleavage showed that cleaved PARP was markedly reduced in R1 and nearly disappeared in R2 (Figure 2c). Thus, our results indicate that despite initial sensitivity to the antibody, the xenografts become resistant over time, and the cell lines generated show cross-resistance to multiple IGF1R antibodies.

Figure 2.

Generation and characterization of IGF1R antibody-resistant rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) cell lines. (a) IGF1R antibody-sensitive Rh41 cells were inoculated intramuscularly into SCID mice. After about 5 weeks, when tumors became palpable, mice were treated with 200 μg/kg i.p. h7C10 or placebo antibody once weekly. The size of the tumors was measured and is shown (n = 10). Two resistant cell lines, R1 and R2, were generated from h7C10-resistant tumor xenografts. (b) RMS cells were plated into 96-well plates. After attachment, cells were treated with indicated concentrations of R1507 for 72 h and analyzed with the ATPLite assay. (c) Rh41 cells and cells from the two resistant lines were treated with 10 μg/ml R1507 for the indicated times. Cell lysates were made and analyzed for the apoptotic biomarker cleaved PARP. Ctrl, control.

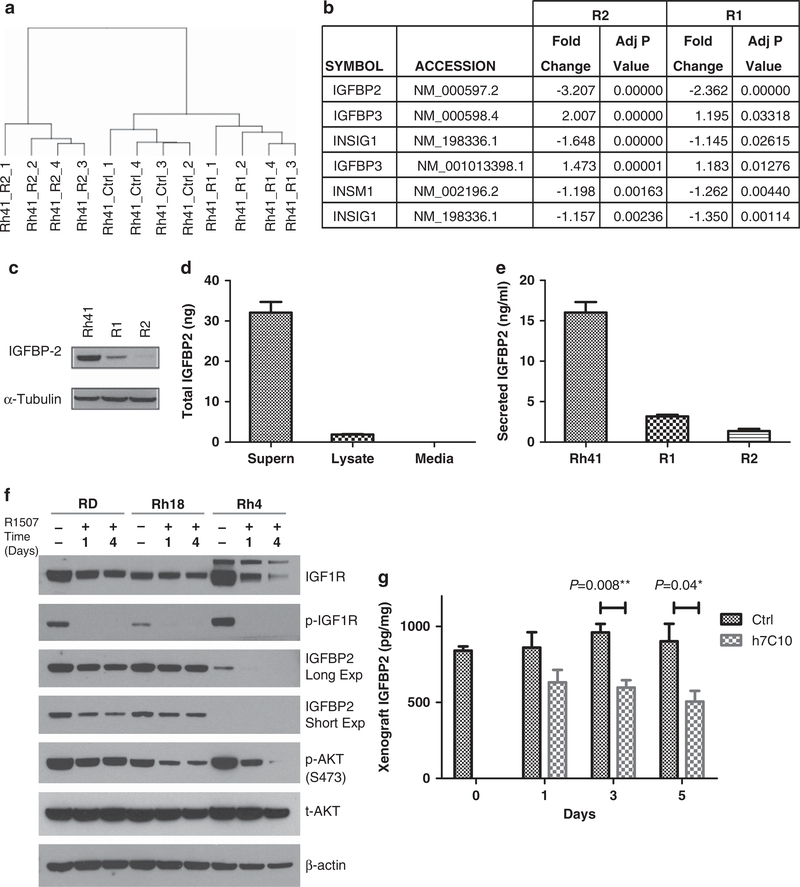

To uncover mechanisms contributing to IGF1R antibody resistance, genome-wide expression analysis was performed with Rh41, R1 and R2 cell lines. Hierarchical clustering analysis showed that Rh41 and R1 were similar to each other than to R2 (Figure 3a). Of the top 1000 genes identified with significantly altered expression from both cell lines based on the adjusted P values, 242 genes were in common (Supplementary Table S2). Visual examination of the top 10 genes with either increased or decreased expression revealed that expression of DSCR and MGP increased, whereas only IGFBP2 expression decreased in both R1 and R2 cells (Supplementary Table S3). To have a more complete understanding of changes in genes specific to IGF signaling and upstream of AKT, we took all 43 known genes and analyzed for those with altered expression in both R1 and R2 cells (Supplementary Table S4). Only four common genes had significantly altered expression when compared with the parental Rh41 cells (Figure 3b, Supplementary Table S5), of which IGFBP2 was the most significantly altered gene in both data sets and had the largest fold change. Thus, the data indicate that IGFBP2 is the most significantly downregulated gene in both resistant cell lines and the most affected gene in the IGF signaling pathway, and there is a unique and strong selection in favor of reduced IGFBP2 expression in the IGF1R antibody-resistant tumor cells.

Figure 3.

Identification of IGFBP2 as the most affected gene specific to IGF signaling and the most downregulated gene in the resistant tumor cells. (a) Hierarchical clustering analysis of expression array data from the Rh41 parental line and the two resistant cell lines, R1 and R2. R2 is more different than Rh41 and R1. (b) IGFBP2 as the most affected gene in the IGF signaling pathway from both R1 and R2. Negative values are indicative of reduced expression when compared with the parental Rh41 cells. (c) Immunoblot analysis of IGFBP2 in cells from the Rh41 line and the resistant R1 and R2 cell lines. (d) Detection of IGFBP2 in cell lysate and 24 h cell culture supernatants of Rh41 cells with electrochemiluminescence (ECL) immunoassay. (e) Reduced IGFBP2 in the culture supernatants of R1 and R2 cells. (f) RMS cell lines were treated with 10 μg/ml of R1507 for the indicated times (days). Cell lysates were made and analyzed for total and phospho-IGF1R (p-IGF1R), total (t-AKT) and phospho-AKT (p-AKT) and IGFBP2 expression with immunoblots. (g) Mice with Rh30 xenografts were treated once with i.p. 200 μg per mouse IGF1R antibody h7C10. Tumors were obtained subsequently at the indicated times. Lysates were analyzed for IGFBP2 protein with an ECL immunoassay (n = 4).

Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates confirmed that IGFBP2 expression was much reduced in both resistant cell lines R1 and R2 (Figure 3c). The reduced protein levels in both resistant cell lines appeared to be greater than two- to threefold as revealed by the expression array data. We further determined the secretion of IGFBP2 from Rh41 cells with a quantitative immunoassay. After 24 h incubation with fresh cell culture media, 95% of the total IGFBP2 was detected in the cell culture media, compared with 5% in the cell lysate (Figure 3d), indicating that IGFBP2 was mostly secreted. The assay was human specific, as the culture media alone gave no detectable signal. The data further showed that there were 5-fold and 12-fold reductions of IGFBP2 from the conditioned media of R1 and R2 cells, respectively (Figure 3e), indicating that the decreased expression led to drastically reduced IGFBP2 secretion from these IGF1R antibody-resistant cells that can bind to free IGFs.

IGF1R antibody induces a short-term and antibody-dependent downregulation of IGFBP2

We further investigated the ability of IGF1R antibody to induce a short-term downregulation of IGFBP2 in vitro and in vivo. Previous studies showed that in mice injected with recombinant IGF1, IGFBP2 was the only IGF-binding protein with increased plasma levels.28 Also, IGFBP2 expression was negatively regulated by Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and positively regulated by activated PI3K/AKT in prostate cancer.29 As Rh41 cells could not be used due to rapid cell death in the presence of IGF1R antibody R1507, we used other RMS cell lines with different sensitivity to IGF1R antibody in cell proliferation assay.23 PAX3-FKHR-positive Rh4, and fusion-negative RD and Rh18 cells. After the treatment with R1507 for 1 or 4 days, decreased IGFBP2 was observed, associated with reduced P-IGF1R (Figure 3f), suggestive of a feedback regulation. In vivo analysis was performed with archived Rh30 RMS xenografts from mice treated with h7C10 for 1, 3 and 5 days.23 The antibody treatment resulted in a small but significant reduction in IGFBP2 in lysates from the xenografts (Figure 3g). These results suggest that IGFBP2 expression may be regulated by IGF1R signaling, in which the reduced signal leads to decreased expression. Interestingly, the IGF1R-resistant R1 and R2 cell lines have constitutively downregulated IGFBP2 (Figure 3c) that is no longer dependent on the inhibition of IGF1R signaling. Thus, our results show that IGFBP2 expression can be rapidly inhibited by an IGF1R antibody that downregulates IGF1R signaling.

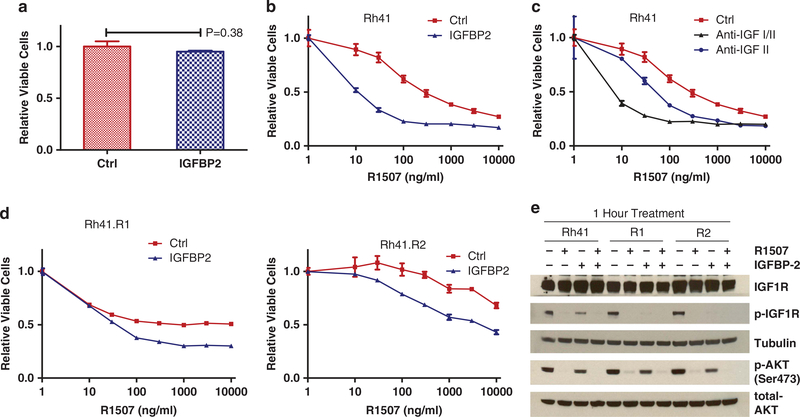

IGFBP2 inhibits IGF1R phosphorylation and its signaling, and enhances the activity of IGF1R antibody to target Rh41 and the antibody-resistant cells

Prior studies show that IGFBP2 can bind to both IGF1 and IGF2, with a greater potency of 2- to 10-fold for IGF2.30,31 IGFBP2 potently reduced cell proliferation in stably transfected 293 cells with high IGFBP2 secretion and the negative effects were completely abolished upon the addition of exogenous IGF1 or IGF2.32 As the antibody-resistant cells have reduced IGFBP2, we expect that the addition of exogenous IGFBP2 could have growth inhibitory effect on Rh41 cells and in part reverse the antibody-resistant phenotype. We examined the effects of purified recombinant IGFBP2 that had an inhibitory ED50 of about 60 ng/ml against 14 ng/ml IGF2-induced cell growth (manufacture data sheet). When used alone, the recombinant IGFBP2 exhibited little growth inhibitory activity against Rh41 cells (Figure 4a). However, the presence of IGFBP2 at a physiological level (300 ng/ml)33 in culture media significantly sensitized Rh41 cells to IGF1R antibody R1507 (Figure 4b), suggesting that IGFBP2 may enhance the activity of IGF1R-targeted antibodies, likely mediated through binding and inhibition of IGF1/2. Similarly, enhanced sensitivity to R1507 was also observed with Rh41 cells that were treated with monoclonal antibodies specific for IGF2 or IGF1/2 ligands (Figure 4c), supporting a similar mechanism of action to IGFBP2. Moreover, the presence of exogenous IGFBP2 partially reversed the resistant phonotype of R1 cells to R1507 (Figure 4d), indicating that the reduced IGFBP2 may contribute to cellular resistance to R1507.

Figure 4.

IGFBP2 inhibits IGF1R and potentiates IGF1R antibody activity against parental and resistant cell lines. (a) Lack of detectable effect on cell growth with IGFBP2. The effects of 0.3 μg/ml recombinant IGFBP2 on Rh41 cells after 3 days incubation. (b) The effects of 0.3 μg/ml of IGFBP2 on Rh41 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of R1507 for 3 days. (c) The effects of 1 μg/ml of anti-IGF1 or anti-IGF1/2 antibody on Rh41 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of R1507 for 3 days. (d) R1 and R2 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of R1507 and 0.3 μg/ml IGFBP2 for 3 days, followed by cell viability analysis. (e) The effects of IGFBP2 (0.3 μg/ml) on phospho-IGF1R (p-IGF1R) and phospho-AKT (p-AKT), either alone or in combination with 10 μg/ml of R1507 for 1 h. Ctrl, control.

We evaluated the role of IGFBP2 in regulating IGF1R and its signaling. By using recombinant IGFBP2, we showed that, at a physiological level (300 ng/ml), IGFBP2 alone inhibited the phosphorylation of IGF1R in Rh41, R1 and R2 cells (Figure 4e), demonstrating a direct inhibitory activity against IGF1R. Although IGFBP2 alone led to a small reduction of phospho-AKT, its combination with IGF1R antibody R1507 was effective in downregulating AKT signaling. These results indicate that IGFBP2 has a role in negatively regulating IGF1R activation in RMS cells.

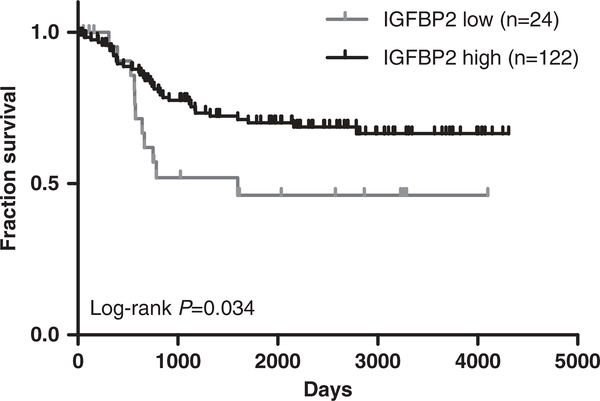

Reduced IGFBP2 expression is associated with worse prognosis for RMS patients

As our data suggested that IGFBP2 could have a role in dampening the activity of IGF1R signaling, we sought to better understand the role of IGFBP2 in RMS patients by examining an expression array database of 146 RMS patients.25,26 It appeared that the lower expression of IGFBP2 was associated with poor overall survival with P = 0.034 (Figure 5, Supplementary Table S6), which is in agreement with our observation that IGFBP2 is inhibitory to IGF1R signaling in RMS cells. Therefore, these results suggest that IGFBP2 expression level is inversely associated with overall survival in RMS.

Figure 5.

High IGFBP2 level associated with better survival in rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) patients. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of 146 RMS patients grouped by IGFBP2 level (Supplementary Table S6).

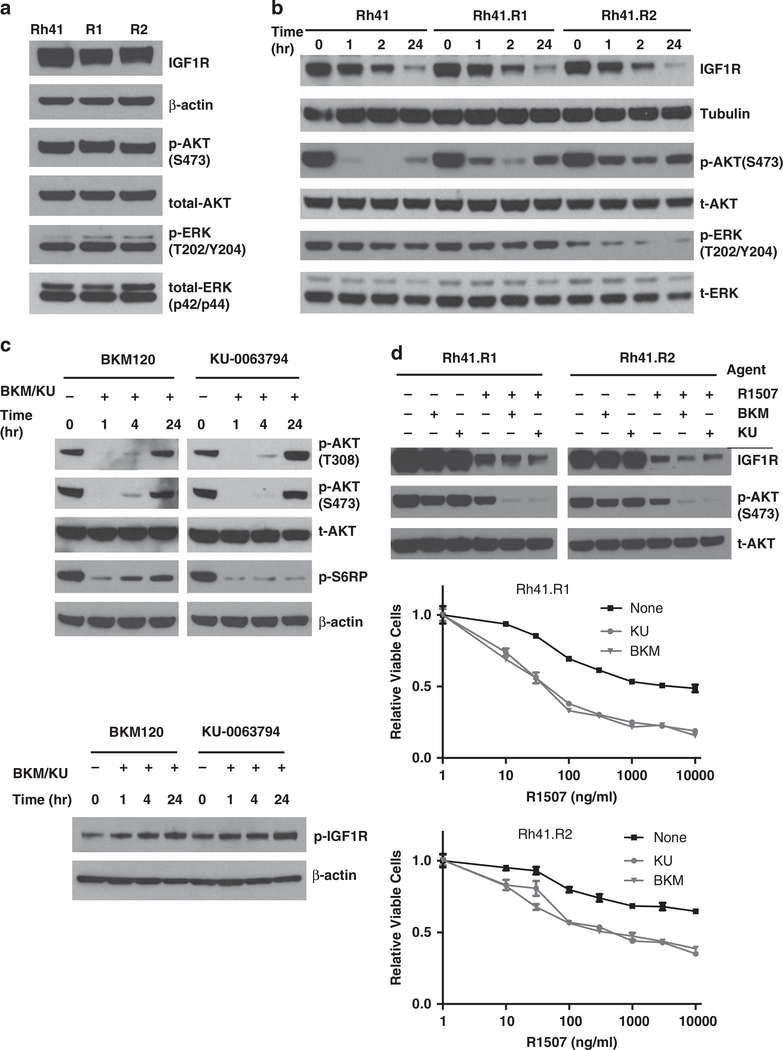

Combining IGF1R antibody with inhibitors to AKT-activating kinases restores the inhibition of AKT signaling and overcomes antibody resistance

To explore the cellular signaling of RMS cells resistant to IGF1R antibody, we examined the effects of the antibody on downregulating AKT and ERK pathways. Although both resistant cell lines show little difference in the steady-state phospho-ERK and phospho-AKT (Figure 6a), their responses to anti-IGF1R antibody blockage is rather different. The IGF1R downregulation had minimal effect on phospho-ERK, indicating the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway was not substantially affected. In contrast, the addition of R1507 significantly inhibited phospho-AKT in Rh41 cells. In comparison, R1507 only modestly inhibited phospho-AKT in both resistant cell lines with the more resistant R2 cells showing less downregulation (Figure 6b). Thus, IGF1R antibody is less effective in suppressing IGF1R-mediated AKT activation in the antibody-resistant cell lines.

Figure 6.

Effects of PI3K and mTOR inhibitors on IGF1R and AKT signaling in RMS cells. (a) Rh41, R1 and R2 cells were analyzed for IGF1R, total (t-AKT) and phospho-AKT (p-AKT) and total and phospho-ERK (p-ERK). (b) The cell lines were treated with 10 μg/ml of IGF1R antibody R1507 for the indicated times. Lysates were analyzed with immunoblots for IGF1R receptor downregulation, and for inhibition of AKT signaling (p-AKT). (c) Rh41 cells were treated with 0.3 μM PI3K inhibitor BKM120, 0.3 μM mTOR inhibitor KU0063794 for the indicated time. Lysates were made and analyzed for p-AKT, S6RP and IGF1R. (d) Resistant R1 and R2 cells were treated with 0.3 μM PI3K inhibitor BKM120, 0.3 μM mTOR inhibitor KU0063794, or IGF1R antibody R1507 alone or in combination as indicated for 24 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for IGF1R, and t-AKT and p-AKT. R1 and R2 cells were treated with increasing concentration of R1507, with or without 0.3 μM BKM120 or KU0063794. Cell viability was determined after 3 days.

The recent development of novel agents targeting protein kinases that phosphorylate AKT provides the possibility of inhibiting AKT activation in these antibody-resistant RMS cells. BKM120 is a class I PI3K-specific inhibitor that is in clinical studies, and KU0063794 is a potent mTORC1/2-specific inhibitor. When Rh41 cells were treated either agent alone at 0.3 μM, despite a rapid initial inhibition of phospho-AKT, it was restored by 24 h (Figure 6c, upper panel). KU0063794, for instance, was still effective in inhibiting phospho-S6RP, a target downstream of mTORC1, suggesting a bypass mechanism for the feedback reactivation of AKT. It was noticeable that there was an small increased phosphor-IGF1R induced by either compound (Figure 6c, lower panel), which could contribute to such feedback activation of phospho-AKT.34 However, the combination of either agent with R1507 significantly enhanced the ability of R1507 to downregulate phospho-AKT in the resistant RMS cells (Figure 6d, upper panel). Cell survival analysis showed that the addition of BKM120 or KU0063794 to the antibody-resistant cells substantially increased the sensitivity of both resistant RMS cell lines to IGF1R antibody R1507 (Figure 6d, lower two panels). Thus, inhibiting kinases phosphorylating AKT significantly increases the sensitivity of IGF1R antibody-resistant RMS cells to R1507, and potentially overcomes their resistance to this antibody.

DISCUSSION

Several previous studies revealed that the activation of alternative receptor tyrosine kinases may serve as a bypass mechanism for IGF1R blockage using in vitro established antibody-resistant cells.35–37 In the study reported here, we used an in vivo tumor model to generate resistant tumor cells. Such a model takes into the consideration of drug availability in tumors and the tumor microenvironment. In two resistant cell lines derived from independent tumors, there was no difference in the antibody target, IGF1R. Instead, IGFBP2 is not only the most dis-regulated gene in the IGF-signaling process but also the most significantly downregulated gene. Further, the more resistant tumor cell line produces the lower amount of IGFBP2. Thus, unlike the intrinsic resistance to IGF1R antibody in RMS where the cell lines with the minimal IGF1R expression are resistant to the antibody, our results indicate that there is a strong selection to constitutively downregulate IGFBP2 expression in the development of acquired resistance to IGF1R antibody in vivo, and raise the issue of potential influence of IGFBP2 on the effectiveness of IGFR1-targeted therapies.

IGFBP2 is one the most abundant IGF-binding proteins. IGFBP2 is generally considered an inhibitory factor via direct binding to IGFs, particularly IGF2,31 which is an autocrine factor significantly overexpressed in RMS.19 Although IGFBP2 knockout mice presented with only a subtle phenotype, transgenic mice overexpressing it have a significant reduction in postnatal body weight gain,38 a phenotype opposite that of transgenic mice expressing IGF1,39 suggesting a growth inhibitory role of IGFBP2. Our data demonstrate a very strong selection for drastic and constitutive reduction of IGFBP2 expression in the antibody-resistance RMS cells. The results show that the sensitive RMS cells become resistant to long-term IGF1R antibody treatment that is not associated with a change in IGF1R expression, but rather the downregulation of IGFBP2. In fact, IGFBP2 is the only constitutively downregulated gene of those specific to IGF signaling and the most commonly downregulated gene of all (Figure 3b and Supplementary Table S3).

The investigation further reveals a straightforward mechanism for resistance in which 95% IGFBP2 is secreted and the antibody-resistant cell lines have 5- to 12-fold reduction of secreted IGFBP2. In addition to binding to IGFs, recombinant IGFBP2 protein is a potent inhibitor of IGFII-induced proliferation of MCF7 cells (Product Sheet, R&D Systems), and is capable of inhibiting IGF1R phosphorylation and activation in RMS cells. Moreover, IGFBP2 protein cooperates with IGF1R antibody to inhibit Rh41 RMS cell growth and survival, with an inhibitory curve very similar to that of a monoclonal antibody against IGFI/II. Thus, with less IGFBP2, a higher concentration of IGF1R antibody is required to achieve the same inhibitory effect. Finally, the addition of IGFBP2 protein partially reverses IGF1R antibody resistance of the established cell lines. Therefore, by drastically and constitutively reducing the production of IGFBP2 that binds and inhibits IGFs, the tumor cells escape IGF1R antibody blockage.

Although the physiological regulation of IGFBP2 expression is still not fully understood, a recent study showed that IGFBP2 is upregulated by leptin, and its overexpression reduces blood glucose.40 Rapid twofold elevated serum levels of IGFBP2 have been reported with mice infused with IGF1,28 which may be dependent on the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway.41 Although IGFBP2 was found to be overexpressed in various malignancies,42 the roles and the mechanism through which IGFBP2 affects tumorigenesis are still unclear. The fact that high expression of IGFBP2 is associated with PTEN mutation and activated PI3K/AKT in glioblastoma and prostate cancer, and is induced by activated PI3K/AKT raised the issue of increased IGFBP2 as a passenger biomarker for this activated pathway.29 Our finding that IGF1R antibody can lead to a small and transient downregulation of IGFBP2 is in agreement with this hypothesis, and provides evidence on negative regulation of IGFBP2 expression by inhibiting IGF1R-AKT signaling. In comparison, the IGF1R antibody-resistant tumor cells have stably and more significantly downregulated IGFBP2, which is independent of IGF1R inhibition. Future work is required to understand the mechanism of IGFBP2 downregulation.

Our analysis confirms the association between increased IGF1R expression and PAX3-FKHR translocation in RMS patients, as we previously suggested based on the whole-genome target identification of the fusion oncoprotein.20 However, it was not expected that increased IGF1R expression would be an independent prognostic biomarker for overall survival. The RMS patients with high IGF1R and PAX3-FKHR have the worst prognosis with a 5-year survival of 8%, far lower than the 70% expected for RMS patients today. This finding strengthens the need for developing IGF1R-targeted combination therapies for this cancer, and raises the possibility that these double positive patients would be the most likely to benefit from them. In contrast, we observed that reduced IGFBP2 is associated with a worse prognosis for RMS patients. This finding is in agreement with our results that IGFBP2 is inhibitory to IGF1R and its signaling and that reduced IGFBP2 may decrease cellular sensitivity to the antibody-mediated blockage of receptor signaling.

Although some studies suggest that IGFBP2 can be a therapeutic target for cancer,43 both IGF1 and IGFBP2 have plasma levels of 100–500 ng/ml, a level that is at least 1000 × higher than plasma vascular endothelial growth factor, which has been successfully managed with a therapeutic antibody, bevacizumab. The much higher abundance of IGF1 and IGFBP2 may make it more difficult to manage therapeutically. However, as more agents targeting downstream kinases become available, such as PI3K and mTORC2 inhibitors, combinations with some of these agents could potentiate the activity of an IGF1R antibody in inhibiting AKT signaling. In two instances, we found that the combination of R1507 with selective inhibitors for either PI3K (BKM120) or mTOR (KU0063794) substantially inhibited AKT signaling. This is consistent with previous findings of feedback regulation that is partially mediated through active IGF1R in RMS.34 Consequently, the addition of a low level of PI3K or mTOR inhibitor partially reverses the resistant phenotype of both IGF1R antibody-resistant cell lines.

In summary, we report here that IGF1R is an independent prognostic marker for survival in patients with RMS. RMS patients with PAX3-FKHR and increased IGF1R have a significantly worse prognosis and are, therefore, most likely to benefit from IGF1R-targeted combination therapies. To uncover factors contributing to the resistance to IGF1R antibodies, expression array analysis reveals that IGFBP2 is the most affected gene in the IGF signaling process and the most significantly downregulated gene in both antibody-resistant cell lines generated with an in vivo model. Interestingly, recombinant IGFBP2 is capable of inhibiting IGF1R activity and its downstream signaling, and enhancing the activity of IGF1R antibody R1507 against the parent and resistant RMS cells. Consistent with its inhibitory role in IGF1R signaling, the results show that IGFBP2 expression is inversely associated with overall survival. Finally, the data show that inhibitors to PI3K and mTOR can collaborate with IGF1R antibody R1507 to both downregulate AKT signaling and reverse the resistance of the RMS cells. We propose that the reduced IGFBP2 is a novel and in vivo mechanism for resistance to IGF1R antibody treatment and suggest that combinations with agents targeting ATK-activating kinases may overcome the resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and reagents

Human RMS cell lines Rh4, Rh18, Rh30 and Rh41 were maintained in RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Anti-IGF1R antibodies h7C10 and R1507 were kindly provided by Merck (Rahway, NJ, USA) and Roche (Nutley, NJ, USA), respectively. Recombinant IGFBP2 was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Monoclonal antibodies specific for IGF2 (M610.27), and against IGF1 and 2 (M708.5) were kindly provided by Dr Dimiter Dimitrov at National Cancer Institute (NCI). PI3K inhibitor BKM120 and mTOR inhibitor KU0063794 were purchased from Sell-eckchem (Houston, TX, USA). Both IGF1R antibody-resistant cell lines, R1 and R2, were generated from two independent IGF1R antibody-resistant tumors. Tumors were dissected and treated with trypsin to release tumor cells, followed by culturing in RPMI-containing medium.

Animal study

Female 4- to 6-week-old SCID mice (code 250) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). The animal study was done as previously described23 except that h7C10 treatment was initiated once tumors reached about 5 mm (subtracted that of the uninoculated leg) to determine its ability to induce tumor regression. The drug was given at 200 μg/mouse i.p. once weekly for the duration of the study. Tumors were measure by caliper weekly. The animal protocol was approved by the NCI Animal Care and Use Committee. At the end of the study, mice were killed and resistant tumors were dissected and treated with trypsin to release cells to establish cell lines.

Cell viability assays

Cell proliferation assays were performed with ATPLite reagent as previously described.23 For cell proliferation assays performed with crystal violet, cells were fixed with 4–8% glutaraldehyde for 15 min, stained with 0.1% crystal violet in 1% EtOH overnight, washed and dried. 10% acetic acid was used for dye extraction that was measured using a Victor 3 plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at 560 nm. Clonogenic assays were performed with 0.5% crystal violet.24

Gene expression array analysis

Cell RNA was isolated with TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) following manufacture manual. Probes were made from the RNA and hybridization was performed with Illumina Expression Beadchip as per manufacturer’s protocols (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Microarray data were extracted with Illumina BeadStudio software and were processed and analyzed with the lumi and limma packages in R/Bioconductor software for differentially expressed genes (http://www.bioconductor.org). Benjamini and Hochberg method was used to adjust the P-values for multiple testing.44 The top 1000 differentially expressed genes were selected by adjusted P-values. The dendrogram was generated with distance calculated by euclidean method and hierarchical cluster by average method.

Immunoblots and electrochemiluminescence assays

Cell and tissue lysates were prepared as previously described.23 The antibodies against IGF1R, phospho-IGF1R, ERK, phospho-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), AKT and phospho-AKT (Ser473), IGFBP2, PARP, β-actin and tubulin were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). The IGFBP2 immunoassay was developed and performed on Meso-Scale Discovery (MSD, Rockville, MD, USA) electrochemi-luminescence assay platform using both detection and capture antibodies from R&D Systems. Briefly, 5 μl of 36 μg/ml anti-IGFBP2 capture antibody was coated per well of MSD standard binding plates overnight at 4 °C. Blocking and sample incubation were performed similar to that previously described for IGF1R quantification.23 For detection, 25 μl of 800 ng/ml anti-IGFBP2 detection antibody was added per well in 5% Tween-20 and 2% normal goat serum and detected with Sulfo-Tag streptavidin with a MSD Sector instrument (Meso Scale Discovery).23

RMS patient gene expression and survival analysis

The expression data on IGF1R and IGFBP2, as well as the survival data, were obtained from Dr Tim Triche from previous reports.25,26 All the normalized intensity data for the microarrays for 203628_at probe (IGF1R) were log2 transformed then median centered. The samples were ordered according to expression levels low to high. Log-rank test was performed for each ranked express level value across samples and the P-value was determined at each threshold and plotted (Supplementary Figure S1). A threshold of 0.826 was selected for the minimization of P-value, which resulted in 26 patients having a higher expression level, and 120 with a lower expression level (Supplementary Table S1). Similar analysis was performed for 202718_at probe (IGFBP2) with results shown in Supplementary Table S6. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of specific groups of patients was performed with GraphPad to determine the log-rank P-values. Cox regression analysis was performed with RCASPAR soft package (http://www.bioconductor.org) with binary IGF1R data using cutoff value described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). All cell-based studies were done in triplicate (n = 3). Data were presented as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical comparisons were determined with Fisher’s exact test using Prism. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Merck and Roche for providing h7C10 and R1507 antibodies to IGF1R, Dimiter Dimitrov for antibodies against IGF2 and IGF1/2, Yuxin Zhang for assistance in Cox regression analysis, Sven Bilke for advice on statistical analysis, Javed Kahn for help with RMS patient expression database analysis and minimization of P value for cutoff selection, Arnulfo Mendoza for animal study, David Petersen for pyrosequencing and Jennifer Crawford for reading the manuscript.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the US National Cancer Institute (NCI). This project was also funded in part with federal funds from the NCI, NIH, under contract N01-CO-12400.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

REFERENCES

- 1.Clemmons DR. Modifying IGF1 activity: an approach to treat endocrine disorders, atherosclerosis and cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007; 6: 821–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurmasheva RT, Houghton PJ. IGF-I mediated survival pathways in normal and malignant cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2006; 1766: 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Insulin Pollak M. and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat Rev 2008; 8: 915–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollak M The insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptor family in neoplasia: an update. Nat Rev 2012; 12: 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Zhou W, Velculescu VE, Kern SE, Hruban RH, Hamilton SR et al. Gene expression profiles in normal and cancer cells. Science (New York, NY) 1997; 276: 1268–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendrickson AW, Haluska P. Resistance pathways relevant to insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor-targeted therapy. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2009; 10: 1032–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yee D Targeting insulin-like growth factor pathways. Br J Cancer 2006; 94: 465–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuen JS, Macaulay VM. Targeting the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor as a treatment for cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2008; 12: 589–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baserga R The insulin-like growth factor-I receptor as a target for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2005; 9: 753–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olmos D, Basu B, de Bono JS. Targeting insulin-like growth factor signaling: rational combination strategies. Mol Cancer Ther 2010; 9: 2447–2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gualberto A, Pollak M. Emerging role of insulin-like growth factor receptor inhibitors in oncology: early clinical trial results and future directions. Oncogene 2009; 28: 3009–3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olmos D, Postel-Vinay S, Molife LR, Okuno SH, Schuetze SM, Paccagnella ML et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary activity of the anti-IGF-1R antibody figitumumab (CP-751,871) in patients with sarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma: a phase 1 expansion cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 129–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tolcher AW, Sarantopoulos J, Patnaik A, Papadopoulos K, Lin CC, Rodon J et al. Phase I, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic study of AMG 479, a fully human monoclonal antibody to insulin-like growth factor receptor 1. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 5800–5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pappo AS, Patel SR, Crowley J, Reinke DK, Kuenkele KP, Chawla SP et al. R1507, a monoclonal antibody to the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, in patients with recurrent or refractory Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: results of a phase II Sarcoma Alliance for Research through Collaboration study. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 4541–4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reidy DL, Vakiani E, Fakih MG, Saif MW, Hecht JR, Goodman-Davis N et al. Randomized, phase II study of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor inhibitor IMC-A12, with or without cetuximab, in patients with cetuximab- or panitumumab-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 4240–4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramalingam SS, Spigel DR, Chen D, Steins MB, Engelman JA, Schneider CP et al. Randomized phase II study of erlotinib in combination with placebo or R1507, a monoclonal antibody to insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor, for advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 4574–4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yee D Insulin-like growth factor receptor inhibitors: baby or the bathwater? J Natl Cancer Inst 2012; 104: 975–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helman LJ, Meltzer P. Mechanisms of sarcoma development. Nat Rev 2003; 3: 685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Badry OM, Minniti C, Kohn EC, Houghton PJ, Daughaday WH, Helman LJ. Insulin-like growth factor II acts as an autocrine growth and motility factor in human rhabdomyosarcoma tumors. Cell Growth Differ 1990; 1: 325–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao L, Yu Y, Bilke S, Walker RL, Mayeenuddin LH, Azorsa DO et al. Genome-wide identification of PAX3-FKHR binding sites in rhabdomyosarcoma reveals candidate target genes important for development and cancer. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 6497–6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crist WM, Anderson JR, Meza JL, Fryer C, Raney RB, Ruymann FB et al. Intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study-IV: results for patients with nonmetastatic disease. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3091–3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petricoin EF 3rd, Espina V, Araujo RP, Midura B, Yeung C, Wan X et al. Phosphoprotein pathway mapping: Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin activation is negatively associated with childhood rhabdomyosarcoma survival. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 3431–3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao L, Yu Y, Darko I, Currier D, Mayeenuddin LH, Wan X et al. Addiction to elevated insulin-like growth factor I receptor and initial modulation of the AKT pathway define the responsiveness of rhabdomyosarcoma to the targeting antibody. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 8039–8048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayeenuddin LH, Yu Y, Kang Z, Helman LJ, Cao L. Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor antibody induces rhabdomyosarcoma cell death via a process involving AKT and Bcl-x(L). Oncogene 2010; 29: 6367–6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davicioni E, Anderson MJ, Finckenstein FG, Lynch JC, Qualman SJ, Shimada H et al. Molecular classification of rhabdomyosarcoma--genotypic and phenotypic determinants of diagnosis: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Am J Pathol 2009; 174: 550–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davicioni E, Anderson JR, Buckley JD, Meyer WH, Triche TJ. Gene expression profiling for survival prediction in pediatric rhabdomyosarcomas: a report from the children’s oncology group. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 1240–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature 2012; 487: 500–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhat RV, Engber TM, Zhu Y, Miller MS, Contreras PC. Identification of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 as a biochemical surrogate marker for the in vivo effects of recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-1 in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997; 281: 522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehrian-Shai R, Chen CD, Shi T, Horvath S, Nelson SF, Reichardt JK et al. Insulin growth factor-binding protein 2 is a candidate biomarker for PTEN status and PI3K/Akt pathway activation in glioblastoma and prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 5563–5568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arai T, Busby W Jr, Clemmons DR. Binding of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) I or II to IGF-binding protein-2 enables it to bind to heparin and extracellular matrix. Endocrinology 1996; 137: 4571–4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Firth SM, Baxter RC. Cellular actions of the insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Endocr Rev 2002; 23: 824–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoflich A, Lahm H, Blum W, Kolb H, Wolf E. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-2 inhibits proliferation of human embryonic kidney fibroblasts and of IGF-responsive colon carcinoma cell lines. FEBS Lett 1998; 434: 329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shariat SF, Lamb DJ, Kattan MW, Nguyen C, Kim J, Beck J et al. Association of preoperative plasma levels of insulin-like growth factor I and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins-2 and −3 with prostate cancer invasion, progression, and metastasis. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 833–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wan X, Harkavy B, Shen N, Grohar P, Helman LJ. Rapamycin induces feedback activation of Akt signaling through an IGF-1R-dependent mechanism. Oncogene 2007; 26: 1932–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potratz JC, Saunders DN, Wai DH, Ng TL, McKinney SE, Carboni JM et al. Synthetic lethality screens reveal RPS6 and MST1R as modifiers of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor inhibitor activity in childhood sarcomas. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 8770–8781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang F, Hurlburt W, Greer A, Reeves KA, Hillerman S, Chang H et al. Differential mechanisms of acquired resistance to insulin-like growth factor-i receptor antibody therapy or to a small-molecule inhibitor, BMS-754807, in a human rhabdomyosarcoma model. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 7221–7231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garofalo C, Manara MC, Nicoletti G, Marino MT, Lollini PL, Astolfi A et al. Efficacy of and resistance to anti-IGF-1R therapies in Ewing’s sarcoma is dependent on insulin receptor signaling. Oncogene 2011; 30: 2730–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoeflich A, Wu M, Mohan S, Foll J, Wanke R, Froehlich T et al. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-2 in transgenic mice reduces postnatal body weight gain. Endocrinology 1999; 140: 5488–5496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathews LS, Hammer RE, Behringer RR, D’Ercole AJ, Bell GI, Brinster RL et al. Growth enhancement of transgenic mice expressing human insulin-like growth factor I. Endocrinology 1988; 123: 2827–2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedbacker K, Birsoy K, Wysocki RW, Asilmaz E, Ahima RS, Farooqi IS et al. Antidiabetic effects of IGFBP2, a leptin-regulated gene. Cell Metab 2010; 11: 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin JL, Baxter RC. Expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 by MCF-7 breast cancer cells is regulated through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Endocrinology 2007; 148: 2532–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoeflich A, Reisinger R, Lahm H, Kiess W, Blum WF, Kolb HJ et al. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2 in tumorigenesis: protector or promoter? Cancer Res 2001; 61: 8601–8610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore LM, Holmes KM, Smith SM, Wu Y, Tchougounova E, Uhrbom L et al. IGFBP2 is a candidate biomarker for Ink4a-Arf status and a therapeutic target for high-grade gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 16675–16679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med 1990; 9: 811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.