Abstract

Purpose

In patient education, there is a need for valid and reliable instruments to assess and tailor empowering educational activities. In this study, we summarize the process of producing two parallel instruments for analyzing hospital patients’ expectations (Expected Knowledge of Hospital Patients, EKhp) and received knowledge (Received Knowledge of Hospital Patients, RKhp) and evaluate the psychometrics of the instruments based on international data. In the instruments, six elements of empowering knowledge are included (bio-physiological, functional, experiential, ethical, social, and financial).

Patients and Methods

The original Finnish versions of EKhp and RKhp were tested for the first time in 2003, after which they have been used in several national studies. For international purposes, the instruments were first translated into English, then to languages of the seven participating European countries, using double-checking procedure in each one, and subsequently evaluated and confirmed by local researchers and language experts. International data collection was performed in 2009–2012 with a total sample of 1,595 orthopedic patients. Orthopedic patients were selected due to the increase in their numbers, and need for educational activities. Here we report the psychometrics of the instruments for potential international use and future development.

Results

Content validities were confirmed by each participating country. Confirmatory factor analyses supported the original theoretical, six-dimensional structure of the instruments. For some subscales, however, there is a need for further clarification. The summative factors, based on the dimensions, have a satisfactory internal consistency. The results support the use of the instruments in patient education in orthopedic nursing, and preferably also in other fields of surgical nursing care.

Conclusion

EKhp and RKhp have potential for international use in the evaluation of empowering patient education. In the future, testing of the structure is needed, and validation in other fields of clinical care besides surgical nursing is especially warranted.

Keywords: empowerment, nursing, patient education as topic, patient participation, patient-centered care, surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

The importance of empowering patient education and patient’s own active engagement has been identified internationally at a strategic level.1–4 In the future, its importance will be even greater due to changes in health-care organizations, shorter contacts with professionals, and increasing options for patients to select and influence their care and treatment. Patient and public involvement in health care, such as patient-centeredness, individualized services and participation in decision-making, is emphasized.2–4 Patient education is a key factor in the care of many health problems,2 such as with orthopedic patients as their hospital stays are reduced and their number is increasing.5 Thus, evaluation of patients’ knowledge processed in empowering patient education is well founded, and there is an international need for instruments for this purpose in health care.

Patient education is one of the main nursing actions, and it has been connected with positive health outcomes6–10 and cost-effectiveness.2 Patient education is reciprocal, reflective action.11,12 With patient empowerment being the main goal, the evaluation of actions is mainly based on patients’ preferences.13–15 To support empowerment, multidimensional knowledge is needed.13,16–19

Studies have demonstrated an increase in patients’ knowledge levels through educational sessions.20–25 However, health-care professionals’ skills in empowering patient education still need improvement.5,14,15,26,27 More comprehensive, multidimensional instruments for evaluation of the knowledge processed in empowering patient education are needed.14 For measurement purposes, we have developed parallel instruments to measure the expected knowledge28–30 as well as received knowledge of patients16,31,32 to identify barriers to patient empowerment by indicating the unfulfilled knowledge expectations. We use the concept of knowledge to emphasize the role of patient education as comprising not only distribution of information to patients but also providing information that can be understood and integrated as part of their cognition and actions.15,16,24

Development of the Instruments Used in the Study

The theoretical background of the instruments Expected Knowledge of Hospital Patients (EKhp, ©Leino-Kilpi, Salanterä, Hölttä 2003) and Received Knowledge of Hospital Patients (RKhp, ©Leino-Kilpi, Salanterä, Hölttä 2003) lies in the concept of empowerment as the main goal of patient education. Empowerment can be defined as the experience of control to know, influence and decide over one’s own life – in this case, a healthy life in particular. It enables self-management, such as problem-solving and decision-making, creating an experience of independence and power.17,33–36

Empowerment has several characteristics that are necessary to specify for measurement purposes. Leino-Kilpi et al37 have introduced the elements of empowerment. Based on literature and a questionnaire with open-ended questions (n=226 patients with chronic disease) discovering the meaning of illness, control over one’s own health and means of support, there are six elements of empowerment:13,16,25,37–39 bio-physiological, functional, experiential, ethical, social, and financial element. The bio-physiological element is concerned with aspects such as illness, symptoms and treatment. The cognitive element is about knowledge of one’s own health and health problems, and the ability to gain, use and evaluate that knowledge. The functional element can be defined as functions of one’s own mind and body, eg, mobility, rest, nutrition, and having the strength and ability to act in relation to the health problem. The experiential element is based on earlier experiences of power and management as well as the emotions connected to them. The ethical element is defined as experience of being valued and respected as an individual, and the feeling of the motive behind the care is to ensure one’s safety. The social element is about power of social interaction with families, other patients and patient unions, for example. The financial element includes the costs and benefits of health or illness and their connection with self-management.14,33,37,40 The elements of empowerment have been tested and used in empowering patient education in numerous nursing contexts.41–53 The structure and items of EKhp and RKhp are based on these elements (40 items divided into six elements of empowerment).33,39 The instruments were created to evaluate the knowledge expectations and received knowledge of patients in the context of empowering patient education. The theoretical hypothesis is that received knowledge corresponding to expected knowledge supports and gives potential for the empowerment of the patient.54

For structuring the instruments, in each subscale, items of expected knowledge or received knowledge were formulated, and content validity was established by a variety of subject matter experts (4 nurses, 4 nurse leaders, 4 nurse researchers, and 4 patients). The instruments were originally developed and piloted in surgical hospital care in collaboration with nurses in clinical practice.16,29,55 EKhp is aimed at evaluating the level of expected knowledge on admission to hospital (in wards or outpatient clinics), and RKhp at evaluating the knowledge received by patients, measured at the end or after their hospital stay.29,30 The instruments are completed by patients, significant others, or in some cases, nurses. Response options are on a 4-point Likert scale (1=fully disagree, 2=disagree to some extent, 3=agree to some extent, 4=fully agree), with higher score indicating higher knowledge expectations (EKhp) or fulfillment of received knowledge (RKhp). The option “Not applicable in my case” is also included. In some studies, the Likert scale is inverted (Table 1).16,29,56

Table 1.

Reported Findings of the EKhp and RKhp Instruments

| Study | Instrument | Sample (Response Rate), Country | Pilot | Cronbach’s Alpha: Total Scale, (Subscales) |

Content Validity | Results: Mean (M), Standard Deviation (SD), (Subscales), Likert Scale Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leino-Kilpi et al 200516 | RKhp | n=237 surgical patients (65%), Finlanda | 40 surgical patients | 0.93 (0.80–0.90) | Theoretical literature, expert panel (3 nurses, 2 physicians, 3 researchers) | M 1.96 (1.59–2.46) SD 0.69 (0.55–0.95) 1=fully agree, 4=fully disagree |

| Heikkinen et al 200728 | EKhp, RKhp | n=120 orthopedic patients (73%), Finlandb | 10 surgical patients | EKhp 0.93 (0.77–0.95) RKhp 0.90 (0.76–0.97) |

Theoretical literature, expert panel (3 nurses, 2 physicians, 3 researchers) | EKhp M 3.35 (3.02–3.60), SD 0.60 (0.48–0.87) RKhp M 2.88 (1.95–3.61), SD 0.72 (0.40–1.01) 1=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree |

| Rankinen et al 200729 | EKhp, RKhp | n=237 surgical patients (65%), Finlanda | 40 surgical patients | EKhp 0.91 (0.87–0.90) RKhp 0.93 (0.80–0.90) |

Theoretical literature, expert panel (3 nurses, 2 physicians, 3 researchers) | EKhp M 1.58 (1.28–1.81), SD 0.46 (0.39–0.65) RKhp M 1.96 (1.59-–2.53), SD 0.69 (0.55–0.94) 1=fully agree, 4=fully disagree |

| Leino-Kilpi et al 200931 | RKhp | n=145 ambulatory surgical patients (73%), Finlandb | 40 surgical patients | 0.90 (0.87–0.93) |

Theoretical literature, expert panel (3 nurses, 2 physicians, 3 researchers) | M 2.86 (2.32–3.56), SD 0.73 (0.48–1.01) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Montin et al 201032 | RKhp | n=123 total joint arthroplasty patients, Finland | 0.96 (0.86–0.98) |

M 1.62 (1.36–2.24), SD 0.59 (0.59–1.03) 1=fully agree, 4=fully disagree |

||

| Ryhänen et al 201230 | EKhp, RKhp | Intervention group (IG) n=50, control group (CG) n=48 breast cancer patients, Finland | 20 breast cancer patients | Both instruments >0.80 | Literature review, panel of experts, pre-testing among 20 breast cancer patients | EKhp First visit to hospital: CG: M 1.42 (1.20–1.70), SD 0.44 (0.38–0.65) IG: M 1.47 (1.22–1.73), SD 0.47 (0.40–0.73) Before surgery: CG: M 1.48 (1.27–1.76), SD 0.47 (0.41–0.68) IG: M 1.59 (1.40–185), SD 0.58 (0.55–0.80 RKhp After surgery: CG: M 2.07 (1.66–2.66), SD 0.56 (0.47–1.03) IG: M 2.14 (1.84–2.68), SD 0.61 (0.59–0.90) After radiotherapy: CG: M 1.82 (1.53–2.05), SD 0.68 (0.58–1.03) IG: M 2.17 (1.90–2.40), SD 0.72 (0.70–0.89) 1=fully agree, 4=fully disagree |

| Ingadottir et al 201491 | EKhp, RKhp | n=290 surgical patients, Finland, Iceland, Swedenc | 30 patients/ country |

EKhp 0.94 (0.85–0.92) RKhp 0.97 (0.86–0.94) |

Research team in every participating country | EKhp M 3.62 (3.40–3.79), SD 0.42 (0.45–0.69) RKhp M 3.03 (2.30–3.52), SD 0.70 (0.61–1.01) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Johansson Stark et al 201492 | EKhp, RKhp | n=320 surgical patients (72%), Finland, Iceland, Swedenc | 30 patients/ country |

EKhp 0.97 (0.87–0.92) RKhp 0.97 (0.83–0.95) |

Research team in each participating country | EKhp M 3.6 (3.4–3.8) SD 0.4 (0.3–0.7) RKhp M 3.0 (2.2–3.5) SD 0.7 (0.1–1.0) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Vaartio-Rajalin et al 201458 | EKhp | n=332 cancer patients, Finland | Comparison of results to interviews (n=53) | (0.78–0.94) | Not reported. | M (1.5–3.7) 1=totally disagree, 4=totally agree |

| Valkeapää et al 201493 | EKhp | n=1,634 orthopedic surgical patients, Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Lithuania, Sweden, Spainc | 30 patients/country | (0.87–0.94) | Research team in each participating country | M 3.56 (3.43–3.72), SD 0.55 (0.50–0.79) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Eloranta et al 201561 | RKhp | n=207 surgical patients (69%), n=177 family members of patients (59%), n=43 nurses (36%), Finlandc |

30 patients, family, 12 members, 12 nurses | Patients (0.84–0.94), family members (0.93–0.97), nurses (0.81–0.91) |

10 members of patient association | Patients: M 3.04 (2.32–3.59), SD 0.57 (0.44–0.93) Family members: M 2.49 (2.08–2.83), SD 0.88 (0.87–1.05) Nurses: M 2.77 (1.96–3.27) SD 0.53 (0.56–0.70) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Ingadottir et al 201557 | EKhp | n=104 heart failure patients (59%), Iceland | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | M 3.68 (3.50–4.00) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Klemetti et al 201594 | EKhp, RKhp | n=943 surgical patients, Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Lithuania, Spain, Swedenc | 30 patients/country | EKhp (0.87–0.94) RKhp (0.89–0.95) |

Research team in each participating country | EKhp M (3.43–3.72) SD (0.50–0.79) RKhp M (2.56–3.36) SD (0.69–1.14) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Leino-Kilpi et al 201563 | RKhp | n=226 patients (85%), Finland | Not reported. | (0.86–0.96) | Not reported. | M 3.16 (2.50–3.46) SD (0.58–1.05) 1=totally disagree, 4=totally agree |

| Sigurdardottir et al 201564 | EKso, RKso | n=615 significant others of hip or knee arthroplasty patients (61%), Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Spain, Swedenc | 30 significant others/country | EKso 0.98 (0.86–0.93) RKso 0.99 (0.85–0.98) |

Research team in each participating country | EKso M 3.59 (3.42–3.76) SD 0.52 (0.47–0.80) RKso M 2.72 (2.29–3.01) SD 1.03 (1.03–1.21) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Johansson Stark et al 201665 | EKhp, RKhp, EKso, RKso | n=299 hip or knee replacement patients, n=306 significant others (66%), Finland, Iceland, Swedenc | 30 patients and 30 significant others/country | EKhp 0.97 (0.87–0.92) RKhp 0.97 (0.86–0.95) EKso 0.97 (0.77–0.97) RKso 0.99 (0.86–0.95) |

Research team in each participating country | EKhp M 3.6 SD 0.4 EKso M 3.6 SD 0.5 |

| Johansson Stark et al 201695 | EKhp, RKhp | n=865 hip or knee replacement patients (79%), Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Swedenc | 30 patients/country | EKhp 0.98 RKhp 0.98 |

Research team in each participating country | Not reported. |

| Klemetti et al 201656 | RKhp | n=1,446 joint arthroplasty patients, Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Lithuania, Spain, Swedenc | 30 patients/country | (0.89–0.95) | Research team in each participating country | Not reported 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Koekenbier et al 201696 | EKhp, RKhp | n=762 hip or knee replacement patients (59%), Finland, Iceland, Greece, Spain, Swedenc | 30 patients/country | Not reported. | Research team in each participating country | EKhp M 3.6 RKhp M 2.9 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Leino-Kilpi et al 201662 | RKhp | n=238 surgical patients whose family members participated the care, n=182 surgical patients whose family members did not participate in the care, Finlandd | Not reported. | 0.99 (0.91–0.98) | Theoretical literature, expert panel, earlier studies | Patients with participating family members: M 3.27 (2.66–3.52) SD 0.7 (0.6–1.11) Patients with nonparticipating family members: M 3.09 (2.48–3.4) SD 0.77 (0.65–1.1) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Pellinen et al 201659 | EKhp | n=252 knee osteoarthritis patients (61%), Finland | Not reported. | 0.98 (0.84–0.93) | Theoretical literature, expert panel, earlier studies | M 3.32 (3.18–3.52) 1=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree |

| Copanitsanou et al 201797 | EKhp, RKhp (solely financial subscale) | n=1,288 total joint arthroplasty patients, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Spain, Swedenc | 30 patients/country | EKhp 0.95 RKhp 0.95 |

Research team in every participating country | EKhp M 3.55 SD 0.64 RKhp M 2.30 SD 1.06 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Salonen et al 201760 | EKhp | n=53 prostate cancer patients (66%), Finland | Not reported. | 0.96 (0.77–0.96) | Not reported. | M (3.00–3.66) SD (0.40–0.82) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Cano-Plans et al 201854 | EKhp, RKhp | n=263 hip and knee replacement patients, Spainc | 30 patients | EKhp 0.91 Rkhp 0.86, 0.94 |

Research team | EKhp M 3.23 (2.97–3.50) SD 0.73 (0.68–1.10) At discharge: RKhp M 2.91 (2.54–3.17) SD 0.89 (0.85–1.27) 6–7 months after discharge: RKhp M 3.28 (2.45–3.69) SD 0.66 (0.62–1.05) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Charalambous et al 201866 | RKho, RKso | n=1,603 orthopedic patients, n=615 significant others, Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Lithuania, Spain, Swedenc | 30 patients and significant others/country | RKhp 0.98 RKso 0.99 |

Research team in each participating country | RKhp M 3.07 (3.36–2.56) SD 0.80 (0.69–1.14) RKso M 2.84 (2.49–3.11) SD 1.03 (1.00–1.22) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Copanitsanou et al 201867 | EKso, Rkso | n=189 significant others of arthroplasty patients (98%), Cyprus, Greece, Spainc | 30 significant others/country | EKso 0.99 RKso 0.99 |

Research team in each participating country | EKso M 3.65 (3.27–3.94) SD 0.54 (0.23–1.86) RKso M 3.14 (2.63–3.83) SD 0.96 (0.27–1.22) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

| Copanitsanou et al 201968 | RKhp, RKso | n=180 hip or knee arthroplasty patients (86%), n=72 significant others, Greecec | 30 patients and significant others | RKhp 0.99 RKso 0.99 |

Research team | RKhp M 2.05 (1.65–2.38) SD 1.06 (0.82–1.33) RKso M 1.71 (1.57–1.81) SD 1.14 (1.03–1.22) |

| Gröndahl et al 201955 | RKhp | n=480 surgical patients, Finlandd | Not reported. | 0.99 (0.91–0.98) | Earlier studies | M 3.33 (2.58–3.47) SD 0.74 (0.63–1.11) 1=fully disagree, 4=fully agree |

Notes: aData collected in the same study; bData collected in the same study; cEmpowering Surgical Orthopedic Patients Through Education study; dData collected in the same study.

Abbreviations: EKhp, The Expected Knowledge of Hospital Patients; RKhp, The Received Knowledge of Hospital Patients; Ekso, The Expected Knowledge of Significant Others; RKso, The Received Knowledge of Significant Others.

In 2003, the EKhp and RKhp instruments were piloted and tested for the first time with 237 adult surgical patients.16,29 After that, the instruments have been used jointly in Finland for orthopedic28 and cancer patients.30 In studies utilizing the instruments separately, EKhp has been used for heart failure patients scheduled for cardiac resynchronization therapy implantation in Iceland57 and for patients with cancer,58 knee osteoarthritis,59 and prostate cancer in Finland.60 RKhp has been used in Finland for patients in ambulatory surgical nursing,31 total joint arthroplasty,32 surgical nursing,55,61,62 medical wards,63 and for family members and nurses in surgical nursing.61 Two parallel instruments to EKhp and RKhp have been used to discover expected knowledge (EKso) and received knowledge of significant others (RKso) (Table 1).64–68

The respondents in the national studies (n=53–480, Table 2) were adult surgical patients, representing both genders, with a mean age of 44–72 years (SD 9–17), mostly employed (12–77%) or retired (17–85%).16,28–32,57–60,62,63 In all of the studies, validity and reliability of EKhp and RKhp have been evaluated, content validity has been confirmed by experts, and internal consistency of the instruments has been sufficient. Internal consistency of the EKhp instrument has been reported in several studies with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.80 to 0.98 and subscales between 0.77 and 0.96,28–30,58–60 while that of the RKhp instrument has been reported to range from 0.80 to 0.99, and subscales between 0.76 and 0.98 (Table 1).16,28–32,62,63

Table 2.

Characteristics of Respondents in Studies Using the EKhp and RKhp Instruments

| Study | Gender n (%) | Additional Question(s) n (%) | Age in Years (Range, SD) | Professional Education n (%) | Employment Status n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leino-Kilpi et al 200516,a | Female 85 (36) Male 152 (64) |

Discharge: Home (94) Other healthcare (6) |

Mean 53 (16–84, SD 17) |

None (30) Undergraduate/ graduate (70) |

Employed (41) Retired (41) Students/ unemployed (18) Employed in health/social care (16) |

| Heikkinen et al 200728,b | Female 65 (54) Male 55 (46) |

- | Mean 46 (19–83, SD 14) |

None 17 (15) Secondary level 48 (43) Upper secondary 30 (27) University 17 (15) |

Employed 77 (64) Retired 20 (17) Home work 4 (3) Student 6 (5) Unemployed 11 (9) Sick leave 2 (2) |

| Rankinen et al 200729,a | Female 84 (36) Male 151 (64) |

1. Chronic disease: Yes 116 (50) No 115 (50) 2. Hospital admission: Elective 171 (72) Emergency 66 (28) 3. Reason for stay: Investigation 26 (11) Procedure 185 (78) Treatment 15 (7) Check-up 5 (2) Other 4 (2) |

Mean 53 (16–84, SD 17) |

- | Employed 97 (41) Retired 96 (40) House work 8 (3) Student 14 (6) Unemployed 11 (5) Other 11 (5) Employed in health/social care 39 (16) |

| Leino-Kilpi et al 200931,b | Female 77 (53) Male 68 (47) |

1. Previous Ambulatory surgery: Yes (51) No (49) 2. Surgery was: Orthopedic (83) Urological/Plastic (17) |

Mean 48 (19–83, SD 15) |

None 25 (19) Vocational school 58 (43) College education 34 (25) Academic degree 18 (13) |

Employed 87 (60) |

| Montin et al 201032 | Female 85 (69) Male 38 (31) |

1. Chronic disease: Yes 80 (65) No 37 (30) 2. Preoperative visit to nurse: Yes 64 (52) No 53 (43) 3. Discharge: Home 105 (85) Healthcare center 17 (14) 4. Positive evaluation of hospitalization: Yes 116 (94) No 7 (6) 5. Time on waiting list in months: For this hospital 1.5 (Range 0–9, SD 1.5) First for another hospital 8.0 (Range 2–36, SD 5.3) 6. Length of present hospital stay in days: 6.7 (Range 4–13, SD 1.7) |

Mean 68 (38–87, SD 10) |

None 37 (30) Secondary level 25 (20) Upper secondary/college 27 (22) Polytechnic/university 13 (11) |

Employed 15 (12) Retired 104 (85) Home work 1 (1) Unemployed 3 (2) |

| Ryhänen et al 201230 | Control group (CG): Female 43 (100) Intervention group (IG): Female 47(100) |

1. Marital status: CG: Married 30 (70) Single/divorced/widow 13 (26) IG: Married 41 (87) Single/divorced/widow 6 (13) 2. Number of children: Mean 1.6 (range 0–4) 3. Monthly income: CG: None 1 (2) Under 1000€ 12 (28) 1000–2000€ 23 (54) Over 2000€ 7 (16) IG: None 1 (2) Under 1000€ 17 (36) 1000–2000€ 31 (66) Over 2000€ 8 (17) |

CG: n=2: 40–45 n=28: 46–60 n=13: 60–69 IG: n=6: 40–45 n=29: 46–60 n=12: 60–69 |

CG: None 10 (23) Secondary level 10 (23) Upper secondary 13 (30) University 10 (23) IG: None 4 (9) Secondary level 10 (21) Upper secondary 24 (51) University 9 (19) |

CG: Employed 27 (63) Retired 12 (28) Unemployed 3 (7) Other 1 (2) Employed in health care 16 (40) IG: Employed 36 (77) Retired 10 (21) Unemployed 1 (2) Other 1 (2) Employed in health care 20 (43) |

| Ingadottir et al 201491,c | Female 152 (52) Male 137 (47) |

1. Discharge: Home 251 (87) Another care institution 32 (11) Other 3 (1) 2. First arthroplasty: Yes 210 (72) No 80 (28) |

Mean 64 (SD 9) | None 82 (28) Secondary level 74 (26) College level 56 (19) Academic degree 39 (13) Other 19 (7) Missing 20 (7) |

Employed 89 (31) Retired 172 (59) Other 23 (8) Missing 6 (2) Employed in health/social care 76 (26) |

| Johansson Stark et al 201492,c | Female 177 (55) Male 143 (45) |

Earlier Arthroplasty: First 244 (76) Second or more 76 (24) |

Mean 64 (SD 11) |

None 77 (26) Secondary level 71 (24) College level 74 (25) Academic level 53 (18) Other 20 (7) |

Employed 146 (46) Retired 154 (49) Other 16 (5) Employed in health/social care 81 (26) |

| Vaartio-Rajalin et al 201458 | Female 212 (64) Male 120 (36) |

1. Hospital visit: Planned 298 (90) Acute 28 (8) 2 Reason for hospital visit: Outpatient care/intervention 151 (45) Follow up 92 (28) Care on ward 53 (16) Diagnostic intervention 11 (3) Surgical intervention 10 (3) Other 15 (5) 3. Chronic disease: Yes 248 (75) No 78 (23) 4. Earlier experience in this hospital: Yes 248 (94) No 20 (6) |

Median 61 (61–85) |

No education 54 (16) Low (professional courses, no exams) 96 (29) Institute 83 (25) University 87 (26) |

Retired 159 (48) Employed outside home 140 (42) Unemployed 15 (5) Working at home 4 (1) Student 3 (1) Work experience in health/social care 245 (74) |

| Valkeapää et al 201493,c | Female 1007 (62) Male 369 (37) |

1. Chronic disease: Yes 720 (44) No 850 (52) 2. Earlier arthroplasty: First 1103 (67) Second or more 322 (20) |

Mean 67 (25–91, SD 10) |

None 694 (43) Secondary level 329 (20) College level 229 (14) Academic 171 (11) Missing 211 (13) |

Employed 416 (26) Retired 875 (54) Working at home 166 (10) Unemployed 30 (2) Other 57 (4) Missing 90 (6) Employed in health/social care 257 (16) |

| Eloranta et al 201561,c | Patients: Female 114 (55) Relatives: Female 106 (60) |

1. Chronic disease: Patients: Yes 103 (50) Relatives: Yes 71 (40) 2.First arthroplasty: Patients: Yes 158 (76) Nurses 3. Occupation: Registered nurse 34 (79) Practical nurse 9 (21) 4. Permanent employment: Yes 39 (93) 5. Work experience in healthcare in years: Mean 18 (range 1–39) 6. Work experience in current unit in years: Mean 10 (range 1–29) |

Patient: Mean 62 (25–86) Relatives: Mean 57 (17–84) Nurses: Mean 44 (24–61) |

Patients: None 62 (30) Secondary level 44 (21) Upper secondary level or higher 36 (17) Relatives: None 41 (23) Secondary level 41 (23) Upper secondary level or higher 48 (27) |

Patients: Employed 65 (32) Retired 128 (63) Other 11 (5) Employed in health/social care 42 (20) Relatives: Employed 88 (50) Retired 73 (41) Other 16 (9) Employed in health/social care 47 (27) |

| Ingadottir et al 201557 | Male 82 (79) | 1. New York Heart Association’s functional classification: Class I 5 (6) Class II 35 (40) Class III 47 (53) Class IV 1 (1) 2. Comorbidities: Hypertension 48 (47) Myocardial infarction 39 (38) Diabetes mellitus 23 (23) Chronic kidney disease 15 (15) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 11 (11) 3. Medication: Beta-blockers 92 (93) Diuretics 82 (83) Statins 60 (61) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors 54 (55) Antiplatelets 49 (50) Anticoagulants 44 (44) Angiotensin II receptor blockers 40 (40) Vasodilators 32 (32) Digitalis 19 (19) 4. Living with spouse/other person: 81 (79) |

Mean 70 (41–90, SD 10) | Basic education (≤9 years) 45 (44) College level 29 (28) Academic degree 27 (27) Other 1 (1) |

Employed 21 (20) Retired 75 (72) Other 8 (8) History of employment within health care 18 (18) |

| Klemetti et al 201594,c | Female 565 (60) Male 378 (40) |

Chronic disease: Yes 445 (48) No 807 (86) |

Mean 67 (25–91, SD 11) |

No vocational education 493 (52) Secondary vocational education 216 (23) College level 138 (15) Academic degree 96 (10) |

Employed 264 (28) Retired 508 (54) Working at home 117 (12) Unemployed 19 (2) Other 35 (4) Employed in health/social care 136 (14) |

| Leino-Kilpi et al 201563 | Female (53) | 1. Marital status: Single 22 (11) Married 128 (62) Divorced 20 (10) Widow 34 (17) 2. Type of admission: Emergency 136 (60) Elective 90 (40) 3. Times in this hospital: First time 51 (25) Second or more 153 (75) 4. Patient room: Single 16 (7) Double 88 (39) Triple or more 90 (40) Placed in corridor due to lack of room 30 (14) 5. Procedures of visit: Investigation 119 (55) Surgical operation (general anesthesia) 4 (2) Surgical operation (local anesthesia) 44 (21) Medication and/or infusion 39 (18) Counseling visit/patient education 5 (2) Other 4 (2) 6. Current state of health: Excellent 10 (5) Good 83 (38) Fairly good 116 (53) Poor 9 (4) 7. Got enough advance information before hospitalization: Yes 154 (78) No 44 (22) 8. Pain during the hospital visit (scale 0–10): Mean 3.95 (SD 3.07) 9. Strength of pain at present (0–10): Mean 1.58 (SD 1.95) 10. Strength of worst pain during hospital period (0–10): Mean 4.72 (SD 3.30) |

Mean 59 | Comprehensive basic education 109 (49) Upper secondary education 9 (4) Vocational education 90 (40) Academic degree 15 (7) |

Employed 67 (29) Unemployed 10 (4) Retired 144 (63) Student 5 (2) Other 4 (2) |

| Sigurdardottir et al 201564,c | Female 397 (64) Male 2019 (35) |

1. Relationship to patient: Spouse 359 (59) Children 191 (31) Other 55 (9) 2. Chronic disease: Yes 140 (23) No 463 (76) |

Mean 57 (17–90, SD 14.5) |

None 196 (37) Secondary 129 (24) College level 106 (20) Academic level 103 (19) |

Employed 311 (53) Retired 196 (27) Stay-at-home 47 (8) Student 28 (5) Unemployed 23 (4) Employed in health care 140 (23) |

| Johansson Stark et al 201665,c | Patients: Female 136 (45) Male 166 (55) Spouses or cohabitants: Female 163 (54) Male 139 (46) |

Patients: 1. Type of arthroplasty: Hip replacement 152 (50) Knee replacement 151 (50) 2. Hospital stay in days: 16 (SD 5) Spouses: 3. Chronic disease: Yes 110 (36) No 191 (63) |

Patients: Mean 65 (34–85, SD 9) Spouses: 64 (27–90, SD 10) |

Spouses: None 63 (24) Secondary 84 (32) College level 66 (25) Academic level 52 (20) |

Spouses: Employed 125 (42) Retired 154 (51) Other 22 (7) Employed in health care 84 (28) |

| Johansson Stark et al 201695,c |

Hip replacement: Female 220 (53) Knee replacement: Female 273 (61) |

1. First arthroplasty: Hip 311 (76) Knee 321 (72) Second or more: Hip 98 (24) Knee 122 (28) 2. Hospital stay in days: Mean 8 (SD 6) 3. Hospital stay as expected: Hip: Yes 370 (91) Knee: Yes 407 (92) |

Hip replacement: Mean 65 (28–91, SD 12) Knee replacement: Mean 67 (35–90, SD 9) |

Hip replacement: None 155 (42) Secondary level 86 (23) College level 79 (21) Academic level 53 (14) Knee replacement: None 214 (53) Secondary level 93 (23) College level 57 (14) Academic level 43 (11) |

Hip replacement: Employed 154 (39) Retired 210 (54) Stay at home 20 (5) Unemployed 6 (2) History of employment in social/health care Yes 80 (20) Knee replacement: Employed 109 (26) Retired 252 (60) Stay at home 53 (12) Unemployed 9 (2) History of employment in social/health care Yes 73 (17) |

| Klemetti et al 201656,c | Female 871 (60) Male 555 (38) |

Chronic disease: Yes 656 (45) No 738 (51) |

Mean 67 (25–91, SD 11) |

None 646 (45) Secondary vocational education 266 (18) College level vocational education 209 (15) Academic degree 145 (10) |

Employed 375 (26) Retired 766 (53) Working at home 157 (11) Unemployed 22 (2) Other 43 (3) Employed in health/social care 239 (17) |

| Koekenbier et al 201696,c | Female 463 (61) Male 299 (39) |

1. Current surgery: Hip arthroplasty 303 (40) Knee arthroplasty 457 (60) 2. First arthroplasty: 588 (77) Second or more 176 (23) |

Mean 68 (28–91) | None 318 (47) Secondary vocational degree 154 (23) College level vocational degree 110 (16) Academic degree 91 (14) |

Employed 204 (28) Retired 425 (58) Stay-at-home 72 (10) Unemployed 11 (1) Other 26 (3) |

| Leino-Kilpi et al 201662,d | Patients whose family members participated in the care (FMP): Female 88 (37) Male 149 (63) Patients whose family members did not participate in the care (no FMP): Female 81 (45) Male 100 (55) |

1. Living arrangements: Live alone FMP 50 (21) no FMP 45 (25) Live with family members FMP 185 (79) no FMP 136 (75) 2. Current admission into hospital: Emergency FMP 73 (32) no FMP 49 (28) Scheduled FMP 155 (68) no FMP 126 (72) 3. Main reason for hospitalization: Examination FMP 14 (6) no FMP 0 (0) Surgical treatment FMP 188 (81) no FMP 141 (83) Medical/infusion therapy FMP 25 (11) no FMP 27 (16) 4. Chronic disease: FMP 120 (52) no FMP 85 (48) 5. Current state of health: FMP: Excellent 16 (7) Good 95 (41) Fairly good 107 (46) Poor 14 (6) No FMP: Excellent 13 (7) Good 77 (43) Fairly good 86 (48) Poor 2 (1) 6. Average length of hospital stay: FMP 4.7 (range 1–30, SD 4.1) no FMP 3.7 (SD 3.1) |

FMP: Mean 61 (16–93, SD 17) no FMP: Mean 55 (18–88, SD 16.5) |

- | - |

| Pellinen et al 201659 | Female 164 (66) Male 83 (34) |

1. Chronic disease: Yes 177 (74) No 63 (26) 2. Knee osteoarthritis counseling: Yes 122 (51) No 116 (49) |

Mean 68 (25–89) | None 84 (40) Lower secondary level 62 (30) Upper secondary level 44 (21) University level 18 (9) |

Employed/home work 28 (12) Retired 186 (82) Unemployed 14 (6) |

| Copanitsanou et al 201797,c | Female 772 (60) Male 486 (38) |

1. Chronic disease: Yes 591 (46) No 637 (49) 2. Reason for hospital stay: Hip arthroplasty 507 (39) Knee arthroplasty 744 (58) 3. First hip/knee arthroplasty 979 (76) Second or more 284 (22) 4. Previously in this hospital: Yes 916 (71) No 329 (26) |

Mean 68 (25–91, SD 10) |

None 547 (42) Secondary vocational education 227 (18) College level vocational education 192 (15) Academic degree 135 (10) Missing 187 (15) |

Employed 336 (26) Retired 671 (52) Working at home 140 (11) Unemployed 17 (1) Other 36 (3) Missing 88 (7) Employed in health or social care 225 (18) |

| Salonen et al 201760 | Male 53 (100) | Marital status: Living alone: 10 (19) Married/Living together 43 (81) |

Mean 67 (32–79, SD 9) |

None 9 (18) Lower secondary level 17 (33) Upper secondary level 9 (18) Academic level 16 (31) |

Employed 15 (28) Retired 38 (72) |

| Cano-Plans et al 201854,c | Female 187 (74) Male 66 (26) |

1. Length of hospital stay in days: Mean 7.6 (SD 1) 2. Chronic disease: Yes 138 (55) No 111 (45) 3. Previous hospital contact: Yes 208 (80) No 52 (20) 4. Operative procedure: Hip arthroplasty 6 (3) Knee arthroplasty 237 (97) 5. Discharge: Home 203 (94) Different care organization 12 (6) |

Mean 70 (38–87, SD 9) |

Education: Basic or less 150 (61) Primary school 53 (22) Secondary school 42 (17) Academic degree: None 170 (81) Vocational education 23 (11) Diploma 9 (4) University degree 8 (4) |

Employed 30 (13) Retired 125 (56) Working at home 64 (28) Unemployed 4 (2) Other 2 (1) Employed in health/social care 18 (7) |

| Charalambous et al 201866,c | Patients: Female (62) Significant others: Female (64) |

1. Chronic disease: Patients (52) Significant others (40) Patients: 2. Knee arthroplasty (61) 3. First knee or hip arthroplasty (67) Significant others: 4. Relationship to patient: Spouses (59) Children (31) |

Patients: Mean 67 (SD 11) Significant others: Mean 57 (17–90, SD 14.5) |

Patients: Lower educational level (54) Significant others: None (32) |

Patients: Retired (47) Significant others: Employed (51) Retired (21) |

| Copanitsanou et al 201867,c | Female (69) Male (31) |

1. Relationship: Spouse (34) Child (53) Other (friend, neighbor) (13) 2. Chronic disease: Yes (27) No (73) |

Mean 53 (19–90, SD 15) |

None (58) Secondary vocational education (19) College-level vocational education (13) Academic degree (10) |

Employed (55) Retired (23) Working at home (housekeeping) (15) Unemployed (7) Other (1) Employed in health/social care (10) |

| Copanitsanou et al 201968,c | Patients: Female 131 (77) Male 49 (27) Significant others: Female 58 (81) Male 13 (18) |

- | Patients: Mean 72 (46–91, SD 8) Significant others: Mean 51 (20–90, SD 15) |

Patients: None 146 (81) Secondary vocational education 17 (9) College level vocational education 8 (4) Academic degree 5 (3) Significant others: None 33 (46) Secondary vocational education 13 (18) College level vocational education 10 (14) Academic degree 11 (15) |

Patients: Employed 7 (4) Retired 108 (60) Working at home 53 (30) Unemployed 3 (2) Other 1 (1) Significant others: Employed 23 (54) Retired 10 (14) Working at home 18 (25) Unemployed 2 (3) Other 1 (1) |

| Gröndahl et al 201955,d | Female 200 (42) Male 277 (58) |

1. Living arrangement: Live alone 115 (24) Live with family member 359 (76) 2. Type of admission into hospital: Emergency 135 (29) Elective 323 (71) 3. First time at hospital generally: Yes 50 (11) No 420 (89) 4. First time in current hospital: Yes 177 (38) No 286 (62) 5. Days spent in this hospital: Mean 4.4 (range 1–42, SD 4.2) 6. Reason for hospitalization: Examination 28 (3) Surgical treatment 373 (39) Medication/infusion therapy 60 (6) Guidance/counseling 481 (51) Other 6 (1) 7. Chronic disease: Yes 228 (49) No 234 (51) 8. Current state of health: Excellent 34 (7) Good 196 (42) Fairly good 216 (47) Poor 17 (4) |

Mean 59 (16–93, SD 17) |

Comprehensive school 169 (36) Matriculation examination 19 (4) Vocational qualification 237 (50) University degree 48 (10) |

Employed 173 (36) Unemployed 24 (5) Retired 255 (53) Stay-at-home mom/ dad 7 (1) Student 18 (4) |

Notes: aData collected in the same study; bData collected in the same study; cEmpowering Surgical Orthopedic Patients Through Education study; dData collected in the same study.

Abbreviations: EKhp, The Expected Knowledge of Hospital Patients; RKhp, The Received Knowledge of Hospital Patients; SD, standard deviation.

The instruments have also been used for multiple purposes. For example, EKhp has been utilized in the development of an inter-professional screening instrument for cancer patients’ education process69 and in a project evaluating patients’ expected knowledge by hospital patients themselves (n=547) and by nurses (n=155) in several different medical wards.70 Moreover, several modified instruments have been made and used based on EKhp and RKhp,71–76 and an instrument assessing the content of provided patient education (EPNURSE) includes parts of EKhp and RKhp.66,68,77 The instruments and their variations have also been used in academic master’s theses in various nursing contexts78–88 and in numerous bachelor’s theses.

For international purposes, the instruments were translated from Finnish to English by native language experts using a standard double-checking translation procedure.89,90 The English version was confirmed by the research team and was then used as original version for international use and for translations in participating countries. The translation procedures in every participating country were also conducted according to standard forward-back translation procedure and were evaluated and confirmed by local researchers in each country. Possible differences and problems were discussed and any amendments accepted by the international research team partners.

In this study, we analyze the psychometrics of the EKhp and RKhp instruments based on international data collected in seven countries. The ultimate goal is to develop the instruments to support international researchers in the field of patient education to find tested, valid instruments for their purposes, and finally, to support the availability of tailored education for patients in different countries.

Patients and Methods

Data Collection

Data for the project Empowering Surgical Orthopedic Patients Through Education (ESOPTE) were collected in countries from the southern (Cyprus, Greece, Spain), northern (Finland, Iceland, Sweden) and central (Lithuania) parts of Europe. Participating countries were chosen to represent a large geographical area and various types of health-care systems.66 The data were collected in one to five hospitals in each country. The inclusion criterion for hospitals was general or university hospital performing surgical orthopedic knee or hip replacement procedures. Health-care professionals provided patient education according to the educational model of each country consisting of similar content consisting of a) the upcoming surgery, b) patients’ self-management and symptom management, c) recovery, and d) health-related quality of life.

The instruments, with cover letters to respondents as well as informed consent forms, were piloted in each country in a corresponding group of patients (30 patients per country). The partners agreed to collect the data from orthopedic patients by using the EKhp and RKhp according to the shared protocol. Designated contact persons in every hospital supported the data collection, ie, distributed the instruments and returned them. EKhp was given to patients prior to the patient’s admission, and RKhp at the end of hospital care. Completed questionnaires were returned to the mailboxes placed on the wards or sent back by mail in a prepaid envelope. Data collection was performed during the years 2009–2012 and results have been reported in 15 international studies (Table 1).54,56,61,64–68,91–97 In this paper, the combined results of all countries form the basis of the analysis.

Sample

The required international sample size was at least 1,540 patients from all participating countries together, based on power calculation of the instruments with a power level of 0.9 and 0.8 differences of mean scores with 0.95 standard deviation within groups at the significance level 0.01.93 Minimum was 220 patients per country. Inclusion criteria for patients attending orthopedic knee or hip replacement surgery for their osteoarthritis disease were 1) ability to understand Finnish/Greek/Icelandic/Lithuanian/Spanish/Swedish, 2) ability to complete the questionnaires independently (or with help of significant others), 3) 18 years of age or older, 4) no diagnosed cognitive disorders, and 5) volunteer to participate in the study.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 22 (IBM Corporation Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, mean, standard deviation, range) were calculated to describe the sample characteristics and main variables. Sum-variables were formulated based on the six theoretical elements of empowerment in the instruments. Internal homogeneity of the scales was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (with the criterion of α ≥ 0.70).

Furthermore, data were also imported to Mplus version 7.1198 for modeling the expected knowledge and received knowledge scale associations using structural equation analysis. First, to determine whether the data fit the hypothetical model, values of the Chi-Square Test of Model Fit, with degrees of freedom (df) and p-value, were calculated. This statistic assesses the model by comparing the Χ2 value of the model to the Χ2 of the null model.99 Chi-square “assesses the magnitude of discrepancy between the sample and fitted covariances matrices”,100 and there should be an essence of a statistical significance.99 As this parameter is known to be influenced by large sample size,99 alternative incremental fit indices were also used for the evaluation of the model fit: comparative fit index (CFI, with the criterion of CFI ≥ 0.95),100 Tucker–Lewis index (TLI, with the criterion of ≥0.95), root-mean-square error of the approximation (RMSEA, with the criterion of <0.06,100 or a stringent upper limit of 0.07)101 and the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR; criterion <0.08). Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), used to assess the suitability of the model if several models are estimated with the same data, indicates to the researcher which of the models is the most parsimonious.102

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 1,595 (76%) hospital patients completed EKhp and 1,343 (64%) completed RKhp. The respondents comprised Icelandic (n=273, 17%), Swedish (n=268, 17%), Spanish (n=260, 16%), Finnish (n=253, 16%), Greek (n=207, 13%), Lithuanian (n=170, 11%) and Cypriot patients (n=164, 10%). The mean age of the respondents was 67 years (SD 10.6, range 25–91). Most of the respondents were female (62%) with vocational education (51%) in addition to primary school as basic education (51%). Over half of the respondents were retired (57%) and nearly a third were employed (27%), with 16% having employment history in health care or social services. Most respondents were admitted to hospital for knee arthroplasty (knee 63%, hip 37%) and had a history of treatment in the same hospital (73%). Forty-six percent of the respondents had a chronic illness, and a minority had had previous arthroplasty or arthroplasties (22%).

Content Validity

The content validity of the EKhp and RKhp instruments was judged with structured criteria including assessment of the instruments’ and subscales’ sufficiency of concreteness for measurement, focus on the expected and received knowledge, similarity to other subscales, items belonging to the subscale, importance in the expected or received knowledge, relevance to the expected or received knowledge, and clarity, coverage, and uniqueness of the instruments.103 Content validity was assessed in every country by expert panels set up by the countries themselves. EKhp and RKhp were evaluated as decent and no changes to the instruments were proposed.

Structural Validity

Confirmatory Factor Analysis in Countries

Data from every participating country were used to test the structural validity of the instruments with confirmatory factor analysis. One latent variable model was built for each country to find out the R-square of each subscale (Table 3). For EKhp, the lowest R-squares were achieved for bio-physiological and financial subscales while the highest were achieved for ethical, functional and social subscales. For RKhp, the lowest R-squares were achieved for bio-physiological, functional and financial subscales, and the highest for ethical subscale.

Table 3.

R-Squares of Subscales of the EKhp and RKhp Instruments

| EKhp | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Countries (n=1595) | Cyprus (n=164) | Finland (n=253) | Greece (n=207) | Iceland (n=273) | Lithuania (n=170) | Spain (n=260) | Sweden (n=268) | |||||||||

| R-square | p-value | R-square | p-value | R-square | p-value | R-square | p-value | R-square | p-value | R-square | p-value | R-square | p-value | R-square | p-value | |

| Bio-physiological | 0.583 | <0.001 | 0.818 | <0.001 | 0.542 | <0.001 | 0.809 | <0.001 | 0.333 | <0.001 | 0.561 | <0.001 | 0.616 | <0.001 | 0.481 | <0.001 |

| Functional | 0.685 | <0.001 | 0.854 | <0.001 | 0.695 | <0.001 | 0.729 | <0.001 | 0.476 | <0.001 | 0.801 | <0.001 | 0.779 | <0.001 | 0.624 | <0.001 |

| Experiential | 0.686 | <0.001 | 0.698 | <0.001 | 0.628 | <0.001 | 0.676 | <0.001 | 0.696 | <0.001 | 0.759 | <0.001 | 0.724 | <0.001 | 0.613 | <0.001 |

| Ethical | 0.794 | <0.001 | 0.814 | <0.001 | 0.797 | <0.001 | 0.887 | <0.001 | 0.642 | <0.001 | 0.844 | <0.001 | 0.697 | <0.001 | 0.679 | <0.001 |

| Social | 0.747 | <0.001 | 0.817 | <0.001 | 0.801 | <0.001 | 0.859 | <0.001 | 0.700 | <0.001 | 0.613 | <0.001 | 0.719 | <0.001 | 0.613 | <0.001 |

| Financial | 0.540 | <0.001 | 0.659 | <0.001 | 0.671 | <0.001 | 0.397 | <0.001 | 0.447 | <0.001 | 0.500 | <0.001 | 0.450 | <0.001 | 0.333 | <0.001 |

| RKhp | ||||||||||||||||

| All Countries (n=1353) | Cyprus (n=161) | Finland (n=186) | Greece (n=186) | Iceland (n=212) | Lithuania (n=157) | Spain (n=227) | Sweden (n=224) | |||||||||

| Bio-physiological | 0.584 | <0.001 | 0.587 | <0.001 | 0.330 | <0.001 | 0.773 | <0.001 | 0.469 | <0.001 | 0.541 | <0.001 | 0.679 | <0.001 | 0.551 | <0.001 |

| Functional | 0.606 | <0.001 | 0.624 | <0.001 | 0.561 | <0.001 | 0.603 | <0.001 | 0.517 | <0.001 | 0.733 | <0.001 | 0.732 | <0.001 | 0.565 | <0.001 |

| Experiential | 0.793 | <0.001 | 0.680 | <0.001 | 0.723 | <0.001 | 0.943 | <0.001 | 0.813 | <0.001 | 0.686 | <0.001 | 0.784 | <0.001 | 0.737 | <0.001 |

| Ethical | 0.890 | <0.001 | 0.836 | <0.001 | 0.836 | <0.001 | 0.989 | <0.001 | 0.883 | <0.001 | 0.760 | <0.001 | 0.886 | <0.001 | 0.819 | <0.001 |

| Social | 0.746 | <0.001 | 0.742 | <0.001 | 0.678 | <0.001 | 0.914 | <0.001 | 0.737 | <0.001 | 0.698 | <0.001 | 0.779 | <0.001 | 0.663 | <0.001 |

| Financial | 0.629 | <0.001 | 0.664 | <0.001 | 0.638 | <0.001 | 0.884 | <0.001 | 0.464 | <0.001 | 0.587 | <0.001 | 0.537 | <0.001 | 0.613 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: EKhp, The Expected Knowledge of Hospital Patients; RKhp, The Received Knowledge of Hospital Patients.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Seven Countries Together

The confirmatory factor analysis of EKhp was performed by first fitting the hypothetical model in the sample of 1,595 patients. The hypothetical model proposed for this study did not demonstrate a good fit with data derived from the sample of patients in seven European countries. Chi-square was 372.006 (df 9) and was statistically significant (p <0.001) not reaching the requirement.99 RMSEA was 0.159 (p <0.001), and CFI of 0.950 and TLI of 0.916 were found. Thus, all of the fit indices demonstrated a need for improvement of the model.

A revised model of EKhp included error covariance between bio-physiological and functional subscales. The model fit improved markedly and fitted fairly (Table 4). The Chi-Square Test of Model Fit was 135.66 (df 8) and was significant (p <0.001) not reaching the criteria.99 CFI of 0.982 and TLI of 0.967 indicated a good fit of the data to the slightly revised model. RMSEA was 0.100 (p <0.0001), not indicating not a good fit (stringent upper limit of 0.07).101

Table 4.

Modeling of the EKhp and RKhp Instruments

| EKhp | RKhp | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothetical Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Hypothetical Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| N of observations | 1595 | 1595 | 1595 | 1595 | 1343 | 1343 | 1343 | 1343 |

| N of dependent variables | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| N of continuous latent variables | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chi-Square Test of Model Fit | 372.061 | 135.661 | 51.728 | 22.779 | 640.999 | 190.283 | 91.120 | 34.393 |

| Degrees of freedom | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 |

| p-value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| RMSEA Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (90% CI) | 0.159 (0.145–0.173) |

0.100 (0.086–0.115) |

0.063 (0.048–0.080) |

0.042 (0.025–0.061) |

0.228 (0.213–0.243) |

0.130 (0.115–0.147) |

0.095 (0.078–0.112) |

0.059 (0.041–0.079) |

| Probability RMSEA ≤ 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.077 | 0.739 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.0000 | 0.187 |

| CFI Comparative Fit Index | 0.950 | 0.982 | 0.994 | 0.998 | 0.910 | 0.974 | 0.988 | 0.996 |

| TLI Tucker-Lewis Index | 0.916 | 0.967 | 0.987 | 0.994 | 0.850 | 0.951 | 0.974 | 0.990 |

| SRMR | 0.030 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.051 | 0.027 | 0.019 | 0.012 |

| AIC | 11700.061 | 11465.661 | 11383.728 | 11356.780 | 14568.924 | 14123.208 | 14026.045 | 13971.318 |

Abbreviations: Ekhp, The Expected Knowledge of Hospital Patients; RKhp, The Received Knowledge of Hospital Patients; SRMR, standardized root-mean-square residual; AIC, Akaike Information Criteria.

The second revised model of EKhp included error covariance between bio-physiological and functional subscales as well as between experiential and functional subscales. The model fit improved markedly and fitted fairly (Table 4). The Chi-Square Test of Model Fit was 51.73 (df 7) and was significant (p <0.001) not reaching the criteria.99 CFI of 0.994 and TLI of 0.987 indicated a good fit of the data to the slightly revised model. RMSEA was 0.063 (p =0.08) indicating a good fit (stringent upper limit of 0.07).101

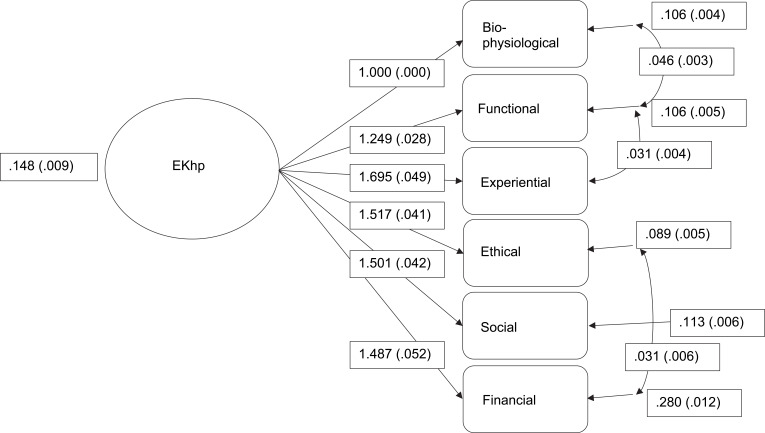

The third revised model of EKhp (Figure 1) included error covariance between bio-physiological and functional subscales, between experiential and functional subscales, as well as between ethical and financial subscales. The model fit improved markedly and fitted well (Table 4). The Chi-Square Test of Model Fit was 22.78 (df 6) and was significant (p <0.001) not reaching the criteria.99 CFI of 0.998 and TLI of 0.994 indicated a good fit of the data to the slightly revised model. RMSEA was 0.042 (p =0.739) indicating a very good fit (stringent upper limit of 0.07).101

Figure 1.

The third revised model of EKhp.

Confirmatory factor analysis of RKhp was performed by first fitting the hypothetical model in the sample of 1,343 patients. The hypothetical model proposed for this study did not demonstrate a good fit with data derived from the sample of patients in seven European countries. Chi-square was 650.00 (df 9) and was statistically significant (p <0.001) not reaching the requirement.99 RMSEA was 0.228 (p <0.001), and CFI of 0.910 and TLI of 0.850 were found. Thus, all of the fit indices demonstrated a need for improvement of the model.

The revised model of RKhp included error covariance between bio-physiological and functional subscales. The model fit improved markedly and fitted fairly (Table 4). The Chi-Square Test of Model Fit was 190.23 (df 8) and was significant (p <0.001) not reaching the criteria.99 CFI of 0.974 and TLI of 0.951 indicated a good fit of the data to the slightly revised model. RMSEA was 0.130 (p <0.0001) indicating not a good fit (stringent upper limit of 0.07).101

The second revised model of RKhp included error covariance between bio-physiological and functional subscales as well as between social and financial subscales. The model fit improved markedly and fitted fairly (Table 4). The Chi-Square Test of Model Fit was 91.120 (df 7) and was significant (p <0.001) not reaching the criteria.99 CFI of 0.988 and TLI of 0.974 indicated a good fit of the data to the slightly revised model. RMSEA was 0.095 (p <0.0001) indicating not a good fit (stringent upper limit of 0.07).101

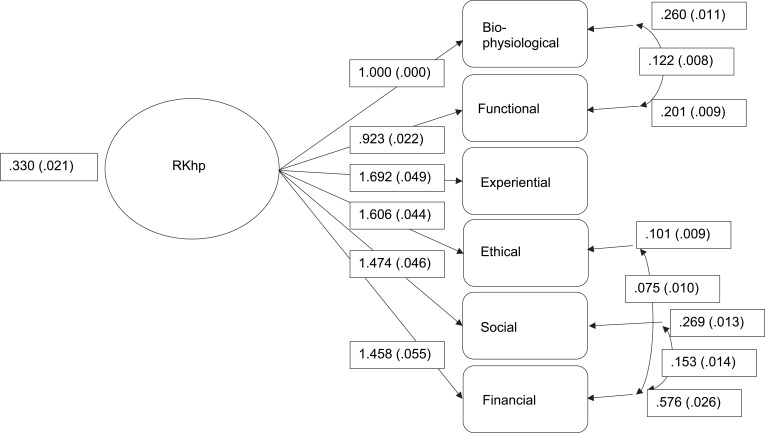

The third revised model of RKhp (Figure 2) included error covariance between bio-physiological and functional subscales, between financial and ethical, as well as between social and financial subscales. The model fit improved markedly and fitted well (Table 4). The Chi-Square Test of Model Fit was 34.393 (df 6) and was significant (p <0.001) not reaching the criteria.99 CFI of 0.996 and TLI of 0.990 indicated a good fit of the data to the slightly revised model. RMSEA was 0.059 (p =0.187) indicating a good fit (stringent upper limit of 0.07).101

Figure 2.

The third revised model of RKhp.

Reliability

Reliability of the instruments was demonstrated with internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha values. In the total EKhp instrument, Cronbach’s alphas between the countries ranged from 0.87 (Iceland) to 0.99 (Lithuania). Subscales ranged between 0.8 and 0.98 in all countries, with the exception of the ethical subscale in Iceland, which was 0.57. Iceland had the lowest values in every subscale (0.57–0.83) except for the financial subscale (0.9).

Between the countries, the Cronbach’s alpha for the total RKhp ranged from 0.97 (Finland and Lithuania) to 0.99 (Greece). In subscales, the lowest values were seen in the functional subscale (in Finland, Greece, Iceland and Sweden, range in all countries 0.83–0.95) and the highest in the financial subscale, being the highest value in several countries: Finland, Greece, Spain and Sweden (range in all countries 0.87–0.99).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the psychometrics of the EKhp and RKhp instruments. This is the first parallel international use of EKhp and RKhp and the evaluation of their psychometrics. Our basic assumption is that instruments for assessment of patient education are necessary due to the current and increasing importance of empowering patient education on European level.1,4 Meeting the knowledge expectations of patients in education is crucial for patient empowerment. Results of earlier studies using EKhp and RKhp suggest discrepancies between the expected and received knowledge, giving rise to concern about individually tailored empowering patient education.94

EKhp and RKhp are parallel instruments: development of such types of instruments is rather complicated, and they are not very common in nursing. EKhp and RKhp were developed based on the theoretical assumption of correspondence between patients’ expectations and received knowledge giving more potential for patient education to be empowering for individual patients. This assumption has received support,9,104 but the connection still needs further testing, especially the connection between expected and/or received knowledge and their relationship with nursing outcomes. This kind of testing would require both narrative designs analyzing patients’ experiences and randomized clinical trials in patient education. Furthermore, we also need more studies based on evidence analyzing the ethical element of empowering knowledge, especially the connection between patient’s right to know and empowering patient education.

Based on the results, EKhp and RKhp are proposed as international instruments with satisfactory psychometric qualities for the evaluation of empowering patient education. In confirmatory factor analyses, some error covariances were found. These relationships were also found in the Spanish versions.105 However, R-square values of subscales were satisfactory, the instruments enabled data collection in all seven countries, and the instruments have been tested with numerous respondents before this international study. However, it is clear that we need to be aware of the constant changes in patients’ responsibilities for their care and treatment in order to enable support to the empowerment of patients, and the structure of the instruments must be modified accordingly. Furthermore, this study was the first one using EKhp and RKhp in most of the participating countries, and potential country-specific factors need further investigation for drawing country-specific conclusions. For instance, in Spain, the financial subscale in both instruments obtained good psychometric values; however, the healthcare context in Spain is mainly based on the public health-care system where patients are not aware of direct costs and therefore, patients do not expect to receive information on financial issues. Nevertheless, both instruments demonstrated ability to capture the expected and received knowledge in orthopedic patients regardless of any country-specific confounding factors. Therefore, our aim to develop and test the instruments for the common European health-care market was successful, and the instruments seem promising for that purpose.

In this study, the instruments demonstrated sufficient internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha. Few alpha values of 0.99 were rather high, indicating that the instruments could be shortened in the future.106 Based on the analysis, however, no specific item in the current form of the instruments could be identified. In the Icelandic data, the ethical subscale in EKhp received a lower alpha (0.57). The Iceland data set is rather small, and due to the possible cultural reasons behind this finding, testing needs to continue. The ethical subscale of EKhp demonstrated sufficient consistency in other Nordic countries (Finland and Sweden) which are culturally fairly similar to Iceland.107

International comparison of empowering patient education presents many challenges. Patient education differs between countries and cultures due to numerous national factors. For example, in some countries, patient education is done with the use of rather static information material in the form of leaflets while in others, this training takes a more structured face-to-face format. Other differing factors might include the points in time when and to what extent the training is delivered. In this study, the assumption is that there is correspondence between countries in the care of orthopedic patients and their education. The earlier published results from this study data have demonstrated similarities internationally; for example, in patient education provided by nurses66 and in differences between the expected and the received knowledge in patient education.94 It is clear, however, that even though the items of the instruments are the same, the patients in different countries could interpret and understand them differently. Nevertheless, international research is important especially in the European region where patients travel across countries, health-care professionals are in the common labor market, and health strategies are shared.1 Thus, it is beneficial to continue to produce information about patient education broadly, across national boundaries. Furthermore, the generation of high-quality cross-border information ensures that the level of training is kept at a high standard. In the future, concept analysis of empowering patient education could provide additional information on this matter. EKhp and RKhp can be advantageous premises for such research.

Instrument development is a long, systematic, and multi-phase process.108,109 Psychometric evaluation of EKhp and RKhp on national and international levels has demonstrated validity and reliability of the instruments. However, further testing of the instruments is warranted due to the constant changes in health care. International research communities are invited to join in the testing of EKhp and RKhp to improve empowering patient education globally.

Limitations

This study has limitations in terms of generalization. Generalization of the results can be applied to hip and knee arthroplasty patients in Europe. The patients were from seven different countries and from many hospitals across the Europe; with caution, the results can thus be applied more generally to arthroplasty patients. Patient education in surgical care contexts is assumed to have many similarities;66 the results may therefore be applicable to other surgical patient groups as well. Outside the context of surgical patients, the instruments have been used successfully in national studies; for example, with patients with cancer or cardiac disease. In the future, international testing of the instruments will need to be applied to other patient groups.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, EKhp and RKhp are promising instruments for international use by researchers and practitioners in the field of hospital care, especially in the field of surgical care. When the instruments are used jointly, they can produce unique information regarding the results of patient education from patients’ perspective: EKhp indicates expected knowledge, that is, the initial situation before patient education, while RKhp uncovers received knowledge. Information provided by the instruments gives potential to support the empowerment of patients. The instruments can be applied in multiple ways in nursing, health care, and research to discover, for example, the effectiveness, quality, or patient-centeredness of patient education.

Recommendations

For empowering patients with educational activities, validated instruments for measuring patients’ expectations (EKhp) and received (RKhp) knowledge are useful. They can be used internationally both in clinical work and research. Instruments are fitting particularly for hospital care, and testing within other contexts in future is needed.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this paper was presented at the STTI (Sigma) 5th Biennial European Conference as a poster presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in Sigma repository: http://hdl.handle.net/10755/20777

Funding Statement

Design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data and writing the manuscript were financially supported by the Academy of Finland. There were also other funding sources: Cyprus: the Cyprus University of Technology; Finland: University of Turku, the Finnish Association of Nursing Research, the Finnish Foundation of Nursing Education; Greece: Faculty of Nursing, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens; Iceland: the Landspitali University Hospital Research Fund, the Akureyri Hospital Science Fund, the University of Akureyri Science Fund, the KEA fund, Akureyri, the Icelandic Nurses’ Association Science Fund; Lithuania: University of Klaipeda; Spain: Colegio Oficial de Enfermeria de Barcelona; and Sweden: the Swedish Rheumatism Association, and the County Council of Östergötland.

Abbreviations

EKhp, The Expected Knowledge of Hospital Patients; RKhp, The Received Knowledge of Hospital Patients; ESOPTE, Empowering Surgical Orthopedic Patients Through Education; CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker–Lewis index; SRMR, standardized root-mean-square residual; AIC, Akaike Information Criteria.

Data Sharing Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this and other published articles [54,56,61,64-68,91-97] (Table 1).

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In all phases of the development of the instruments, principles of research ethics have been followed, and ethical approvals and permissions for data collection have been obtained. In the international data reported in this article, the respondents were informed of the purpose of the study and principles of anonymity and confidentiality. Every participant gave a written informed consent. All data have been stored and coded, and identification of individual respondents in reports is not possible. Ethical approvals were given in each participating country according to their national standards by regional ethical authorities (Cyprus: Ministry of Health Research and Ethics Committee, Republic of Cyprus, Y.Y.15.6.17.9(2); Finland: Ethics Committee of Hospital District of Southwest Finland, ETMK: 102/180/2008; Greece: Ethics Committee of the Department of Nursing, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 3029/17.08.2010; Iceland: the National Bioethics Committee, 09-084-SI; Lithuania: Ethical Research Committee, Klaipeda University, Sv-14, 17/04/2009; Spain: Ethical and research committee of International University of Catalonia, 2010/5955, and Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, ref # 2010/5955 * 2010/5915; Sweden: Regional ethical committee of Linköping University, Dnr. M69-09), as well as permissions for data collection.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Health 2020 - A European policy framework and strategy for the 21st century. World Health Organization, Regional office for Europe; 2013. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/199532/Health2020-Long.pdf. Accessed December18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Caring for quality in health: lessons learnt from 15 reviews of health care quality. 2017. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Caring-for-Quality-in-Health-Final-report.pdf. Accessed December18, 2019.

- 3.European Commission. Blocks: tools and methodologies to assess integrated care in Europe. Report by the expert group on health systems performance assessment. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Commission. Sweeping changes to upgrade Europe’s health systems – EU support for health system efficiency. Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency, European Commission; 2019. Available from: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/e6c91cd7-e952-11e8-b690-01aa75ed71a1/language-en?WT.mc_id=Selectedpublications&WT.ria_c=19980&WT.ria_f=3171&WT.ria_ev=search. Accessed December18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eloranta S, Katajisto J, Leino-Kilpi H. Orthopaedic patient education practice. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2016;21:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijotn.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson K, Nuutila L, Virtanen H, Katajisto J, Salanterä S. Preoperative education for orthopaedic patients: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(2):212–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03381.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klemetti S, Kinnunen I, Suominen T, et al. Active preoperative nutrition is safely implemented by the parents in pediatric ambulatory tonsillectomy. Ambulatory Surg. 2010;16(3):75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klemetti S, Kinnunen I, Suominen T, et al. The effect of preoperative fasting on postoperative thirst, hunger and oral intake in paediatric ambulatory tonsillectomy. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(3–4):341–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siekkinen M, Kesänen J, Vahlberg T, Pyrhönen S, Leino-Kilpi H. Randomized, controlled trial of the effect of e-feedback on knowledge about radiotherapy of breast cancer patients in Finland. Nurs Health Sci. 2015;17(1):97–104. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao FF, Suhonen R, Koskinen S, Leino-Kilpi H. Theory-based self-management educational interventions on patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(4):812–833. doi: 10.1111/jan.13163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svavarsdóttir MH, Sigurðardóttir ÁK, Steinsbekk A. How to become an expert educator: a qualitative study on the view of health professionals with experience in patient education. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:87. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0370-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Posma ER, van Weert JC, Jansen J, Bensing JM. Older cancer patients’ information and support needs surrounding treatment: an evaluation through the eyes of patients, relatives and professionals. BMC Nurs. 2009;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-8-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson K, Leino-Kilpi H, Salanterä S, et al. Need for change in patient education: a Finnish survey from the patient’s perspective. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):239–245. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00223-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaartio-Rajalin H, Huumonen T, Iire L, et al. Patient education process in oncologic context: what, why, and by whom? Nurs Res. 2015;64(5):381–390. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heli V-R, Helena L-K, Liisa I, Kimmo L, Heikki M. Oncologic Patientsʼ knowledge expectations and cognitive capacities during illness trajectory. Holist Nurs Pract. 2015;29(4):232–244. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leino-Kilpi H, Johansson K, Heikkinen K, Kaljonen A, Virtanen H, Salanterä S. Patient education and health-related quality of life: surgical hospital patients as a case in point. J Nurs Care Qual. 2005;20(4):307–318. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200510000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Virtanen H, Leino-Kilpi H, Salanterä S. Empowering discourse in patient education. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(2):140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koponen L, Rekola L, Ruotsalainen T, Lehto M, Leino-Kilpi H, Voipio-Pulkki LM. Patient knowledge of atrial fibrillation: 3-month follow-up after an emergency room visit. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61(1):51–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakellari E, Athanasopoulou C, Kokkonen P, Sourander A, Leino-Kilpi H. Validation of the youth efficacy/empowerment scale - mental health Finnish version. Psychiatriki. 2019;30(3):235–244. doi: 10.22365/jpsych.2019.303.235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson K, Salanterä S, Katajisto J. Empowering orthopaedic patients through preadmission education: results from a clinical study. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klemetti S, Kinnunen I, Suominen T, et al. The effect of preoperative nutritional face-to-face counseling about child’s fasting on parental knowledge, preoperative need-for-information, and anxiety, in pediatric ambulatory tonsillectomy. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(1):64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryhänen AM, Siekkinen M, Rankinen S, Korvenranta H, Leino-Kilpi H. The effects of Internet or interactive computer-based patient education in the field of breast cancer: a systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salonen A, Ryhänen AM, Leino-Kilpi H. Educational benefits of internet and computer-based programmes for prostate cancer patients: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(1):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kesänen J, Leino-Kilpi H, Lund T, Montin L, Puukka P, Valkeapää K. The knowledge test feedback intervention (KTFI) increases knowledge level of spinal stenosis patients before operation-a randomized controlled follow-up trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):1984–1991. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kesänen J, Leino-Kilpi H, Lund T, Montin L, Puukka P, Valkeapää K. Increased preoperative knowledge reduces surgery-related anxiety: a randomised clinical trial in 100 spinal stenosis patients. Eur Spine J. 2017;26(10):2520–2528. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-4963-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rantanen M, Johansson K, Honkala E, Leino-Kilpi H, Saarinen M, Salanterä S. Dental patient education: a survey from the perspective of dental hygienists. Int J Dent Hyg. 2010;8(2):121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2009.00403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Virtanen H, Leino-Kilpi H, Salanterä S. Learning about a patient-empowering discourse: testing the use of a computer simulation with nursing students. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2015;5(6):15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heikkinen K, Leino-Kilpi H, Hiltunen A, et al. Ambulatory orthopaedic surgery patients’ knowledge expectations and perceptions of received knowledge. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60(3):270–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04408.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rankinen S, Salanterä S, Heikkinen K, et al. Expectations and received knowledge by surgical patients. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(2):113–119. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzl075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryhänen AM, Rankinen S, Siekkinen M, Saarinen M, Korvenranta H, Leino-Kilpi H. The impact of an empowering internet-based breast cancer patient pathway programme on breast cancer patients’ knowledge: a randomised control trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(2):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leino-Kilpi H, Heikkinen K, Hiltunen A, et al. Preference for information and behavioral control among adult ambulatory surgical patients. Appl Nurs Res. 2009;22(2):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2007.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montin L, Johansson K, Kettunen J, Katajisto J, Leino-Kilpi H. Total joint arthroplasty patients’ perception of received knowledge of care. Orthop Nurs. 2010;29(4):246–253. doi: 10.1097/NOR.0b013e3181e51868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leino-Kilpi H, Luoto E, Katajisto J. Elements of empowerment and MS patients. J Neurosci Nurs. 1998;30(2):116–123. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199804000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuokkanen L, Leino-Kilpi H. Power and empowerment in nursing: three theoretical approaches. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(1):235–241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01241.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoberer D, Leino-Kilpi H, Breimaier HE, Halfens RJ, Lohrmann C. Educational interventions to empower nursing home residents: a systematic literature review. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1351–1363. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S114068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pekonen A, Eloranta S, Solt M, Virolainen P, Leino-Kilpi H. Measuring patient empowerment – a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(4):777–787. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leino-Kilpi H, Mäenpää I, Katajisto J. Empowerment of Patients with Longterm Disease. Development of the Evaluation Basis for the Quality of Nursing Care. 1st ed. Helsinki: STAKES; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siekkinen M, Salanterä S, Rankinen S, Pyrhönen S, Leino-Kilpi H. Internet knowledge expectations by radiotherapy patients. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(6):491–498. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000339245.53077.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kesänen J, Leino-Kilpi H, Lund T, Montin L, Puukka P, Valkeapää K. Spinal stenosis patients’ visual and verbal description of the comprehension of their surgery. Orthop Nurs. 2019;38(4):253–261. doi: 10.1097/NOR.0000000000000572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leino-Kilpi H, Mäenpää I, Katajisto J. Nursing study of the significance of rheumatoid arthritis as perceived by patients using the concept of empowerment. J Orthop Nurs. 1999;3(3):138–145. doi: 10.1016/S1361-3111(99)80051-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johansson K, Salanterä S, Katajisto J, Leino-Kilpi H. Patient education in orthopaedic nursing. J Orthop Nurs. 2002;6(4):220–226. doi: 10.1016/S1361-3111(02)00094-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johansson K, Salanterä S, Heikkinen K, Kuusisto A, Virtanen H, Leino-Kilpi H. Surgical patient education: assessing the interventions and exploring the outcomes from experimental and quasiexperimental studies from 1990 to 2003. Clin Eff Nurs. 2004;8(2):81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cein.2004.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johansson K, Salanterä S, Katajisto J, Leino-Kilpi H. Written orthopedic patient education materials from the point of view of empowerment by education. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(2):175–181. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00036-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryhänen AM, Johansson K, Virtanen H, Salo S, Salanterä S, Leino-Kilpi H. Evaluation of written patient patient educational materials in the field of diagnostic imaging. Radiography. 2008;15(2):e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2008.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heikkinen K, Suomi R, Jääskeläinen M, Kaljonen A, Leino-Kilpi H, Salanterä S. The creation and evaluation of an ambulatory orthopedic surgical patient education web site to support empowerment. Comput Inform Nurs. 2010;28(5):282–290. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181ec23e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heikkinen K, Salanterä S, Suomi R, Lindblom A, Leino-Kilpi H. Ambulatory orthopaedic surgery patient education and cost of care. Orthop Nurs. 2011;30(1):20–28. doi: 10.1097/NOR.0b013e318205747f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heikkinen K, Salanterä S, Leppänen T, Vahlberg T, Leino-Kilpi H. Ambulatory orthopaedic surgery patients’ emotions when using different patient education methods. J Perioper Pract. 2012;22(7):226–231. doi: 10.1177/175045891202200703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryhänen AM, Rankinen S, Tulus K, Korvenranta H, Leino-Kilpi H. Internet based patient pathway as an educational tool for breast cancer patients. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(4):270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siekkinen M, Leino-Kilpi H. Developing a patient education method - the e-Knowledge Test with feedback. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;180:1096–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryhänen AM, Rankinen S, Siekkinen M, Saarinen M, Korvenranta H, Leino-Kilpi H. The impact of an empowering Internet-based breast cancer patient pathway program on breast cancer patients’ clinical outcomes: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(7–8):1016–1025. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]