Abstract

γ-Aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors are key mediators of central inhibitory neurotransmission and have been implicated in several disorders of the central nervous system. Some positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of this receptor provide great therapeutic benefits to patients. However, adverse effects remain a challenge. Selective targeting of GABAA receptors could mitigate this problem. Here, we describe the synthesis and functional evaluation of a novel series of pyrroloindolines that display significant modulation of the GABAA receptor, acting as PAMs. We found that halogen incorporation at the C5 position greatly increased the PAM potency relative to the parent ligand, while substitutions at other positions generally decreased potency. Mutagenesis studies suggest that the binding site lies at the top of the transmembrane domain.

Keywords: GABAA receptor, Cys-loop, positive allosteric modulator, ion channel, pyrroloindoline

Some key mediators of central inhibitory neurotransmission are γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors, and as such these receptors have been drug targets for numerous central nervous system (CNS) disorders.1−3 The GABAA receptor is an anion-selective, pentameric, ligand-gated ion channel that is part of the larger Cys-loop receptor family. A functional receptor results from the assembly of five homologous subunits. A total of 19 homologous subunits exist, and they assemble into at least 30 different functional subtypes in vivo.4 Some types, including those comprised of α1β2γ2 subunits, are predominantly expressed at the postsynaptic termini and mediate phasic inhibition, while others are located at extrasynaptic sites and mediate tonic inhibition.4−6 The large diversity of subtypes and differential localization in the brain emphasize their importance, but also present a challenge, as current GABAA receptor therapeutics modulate a broad range of subtypes, which can result in adverse effects.

Each GABAA subunit consists of an N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD), a transmembrane domain (TMD) that comprises four transmembrane α-helices (M1-M4), an extracellular M2-M3 loop and C-terminus, and an intracellular domain composed predominantly of the M3-M4 loop.7 Receptor activation occurs upon binding of an agonist to the orthosteric site, which is located in the ECD at the β+/α– subunit interfaces. This activation can be modulated by additional binding of other ligands to several allosteric sites on the pentameric complex.8 Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) potentiate the evoked response by an agonist, while negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) inhibit that response.9 Over the years various modulators of GABAA receptors have been identified and several of the positive allosteric modulators are widely used to treat anxiety and panic disorders.9,10

Although GABAA receptor modulators have a proven therapeutic benefit, adverse effects remain a problem.11,12 Additionally, elucidating functions of individual subtypes is crucial for a better understanding of the GABAA receptor’s role in health and disease. Therefore, recent efforts have focused on finding subtype-selective modulators. Various novel modulators have been derived for the α+/β– interface.13,14 For example, a series of pyrazolopyridinones developed by Blackaby et al. showed increased selectivity for α3β3γ2 over α1β3γ2.15 Two different series of pyrazoloquinolinones exhibited selectivity for α6β3γ2 and β1-containing receptors, respectively.16,17

Physostigmine (1, Figure 1), also known as eserine or antilirium, is a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor18 that has been used to treat glaucoma and delayed gastric emptying.19,20 In addition, it has been found to potentiate and inhibit nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, another member of the Cys-loop receptor family.21−23

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of selected pyrroloindolines.

As a result of our interest in the synthesis of pyrroloindoline natural products, we have prepared a number of new, non-natural pyrroloindoline compounds.24−26 Given their structural similarity to other modulators of Cys loop receptors, we screened a representative collection of these structures and found that compounds bearing aryl substitution at C8a can act as PAMs of GABAA receptors.27,28 Here, we report the synthesis of pyrroloindoline (+)-2 (Figure 1) and modification of this scaffold by substitution at N1, C3a, C5, and C8a, yielding a novel series of GABAA receptor ligands. All of the compounds were tested for agonism and allosteric modulation properties at the human α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor, the most abundant GABAA subtype in the adult brain, expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes via two-electrode voltage clamp electrophysiology. Additionally, we performed mutagenesis experiments to identify the binding site of these ligands.

Results and Discussion

The synthesis of the pyrroloindoline framework commenced with protection of tryptamine (3) to provide carbamate 4 (Scheme 1). Pd-catalyzed C2 arylation with iodobenzene under microwave conditions gave 2-phenyl tryptamine 5 in 77% yield.29 Various approaches were investigated for effecting oxidative cyclization of 5.30 Although there are many examples of related cyclizations of tryptamine and tryptophan derivatives,24,31−35 we found that many of these conditions were unsuitable for tryptamine 5, presumably due to the phenyl substituent at C2. After extensive experimentation, it was found that oxidative cyclization of 5 by treatment with N-chlorosuccinimide followed by water afforded C3a-hydroxy pyrroloindoline (±)-6 in 85% yield. Reduction of carbamate (±)-6 with Red-Al provided the N1-methyl pyrroloindoline (±)-2.31 Attempts to render the cyclization of 5 to 6 enantioselective have thus far been unsuccessful;35 however, the enantiomers of both compounds (±)-6 and (±)-2 can be resolved using preparative SFC with a chiral stationary phase. X-ray crystallography confirmed the structure and absolute stereochemistry of (+)-2.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the Pyrroloindoline Scaffold.

In a preliminary screen, five pyrroloindoline compounds, including (±)-2, were tested for modulation of eight pentameric ligand-gated ion channels (pLGICs): muscle type nAChR, α4β2 nAChR, α7 nAChR, 5-HT3A receptor, α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor, α1β2 GABAA receptor, GluR2, and the glycine receptor. This assay identified pyrroloindoline (±)-2 as a potent PAM of the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor (Table S1 and Figure S1).27,28 Although no GABAA receptor activity has been previously reported for physostigmine, compound (±)-2 appears to selectively potentiate α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors over other Cys-loop receptors.

Based on the selective PAM profile of (±)-2, we decided to further characterize this ligand. We set out to determine if both enantiomers are active at the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor. Enantiomer-specific effects would imply a specific drug–receptor interaction, rather than some more generic effect such as altering membrane properties. To assess functional effects, we used a similar two-electrode voltage clamp protocol to one previously described by Marotta et al.28 Briefly, the current responses of three identical EC50 doses of GABA were recorded, followed by a dose of the test-ligand at 40 μM. After a 30 s incubation, a dose was applied containing both GABA at its EC50 and the test-ligand at 40 μM. Finally, two doses of GABA EC50 were applied. The first three GABA doses establish a baseline of the GABA response at that concentration, and the purpose of the last two GABA doses is to verify proper functioning of the receptor post modulation and control for independent rise in current amplitude. Of the two (±)-2 enantiomers, only (+)-2 showed a meaningful potentiation of the EC50 GABA dose, with a mean of 16 ± 4.1%, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2.

Functional effects of pyrroloindoline (±)-2 on the α1β2γ2 and α1β2 GABAA receptor subtypes. (A) Wave forms of the α1β2γ2 current responses from a GABA EC50 only dose, a 40 μM (±)-2 only dose, and coapplication of GABA EC50 and 40 μM (±)-2. (B) Relative modulation of a GABA EC50 response of the α1β2γ2 and α1β2 GABAA receptor subtypes by (±)-2 and the individual enantiomers. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA).

To determine activity at the α1β2 subtype and consequent involvement of the γ2 subunit in potentiation, we performed the same experiment for this subtype. For (±)-2 a mean potentiation of 28 ± 5.2% was observed (Figure 2). Similar to the observations for the α1β2γ2 subtype, (+)-2 showed increased potentiation over (−)-2 with mean values of 17 ± 2.6% and 9.2 ± 1.1%, respectively (Figure 2B and Table S2). These results demonstrate that the γ2 subunit is not required for potentiation of the α1β2γ2 receptor by (±)-2.

The amplitude of potentiation is dependent on several factors, among which are both the PAM concentration and the GABA concentration at which we tested the modulation. Next, we determined the effect of 40 μΜ (±)-2 on the GABA EC50 (ΔEC50((±)-2)) at the α1β2γ2 receptor. The observed (±)-2-induced shift in GABA EC50 is 13 μM as shown in Figure 3A and Table S3. This shift is comparable to the induced shift seen for this subtype by the benzodiazepine Triazolam, 16–50 μΜ.36 Moreover, we wanted to determine the potency of the pure enantiomer (+)-2. Well-studied modulators, such as flurazepam and zolpidem, have EC50s in the nanomolar range when coapplied with GABA EC2–5, being 270 nM and 340 nM, respectively.37 The PAM tested here, (+)-2, appears to be less potent with an EC50 of 110 μΜ when coapplied with GABA EC5, as shown in Figure 3B and Table S3.

Figure 3.

Functional characterization of pyrroloindoline (±)-2 at the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor. (A) (±)-2-induced shift in GABA EC50. A 40 μM concentration of (±)-2 was used here. (B) (+)-2 EC50 coapplied with GABA EC5 doses. The peak current at GABA EC5 was subtracted from all responses.

Having established that pyrroloindoline (+)-2 acts as a PAM on the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor, further potentiation experiments used the GABA EC10–15 instead of EC50. Using the EC10–15 allows for a larger potentiation window than EC50, which enables the detection of more subtle functional differences between GABAA mutants or pyrroloindoline analogues. Figures 2B and 4C illustrate this difference in modulation potency for (±)-2. For the α1β2γ2 subtype, (±)-2 causes a 62% potentiation of the GABA EC10 response, while at the GABA EC50 this is only 17%.

Figure 4.

Functional effects of pyrroloindoline (±)-2 on α1β2γ2 and α1β2 GABAA receptor mutants. (A) Side view of the human α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor with the probed residues highlighted in pink (PDB ID: 6D6T). (B) Extracellular view into the pore with GABA and BZ sites indicated with arrows. (C) Relative modulation of GABA10–15 responses by (±)-2. ECD mutants and TMD mutants of α1β2γ2 are in blue and dark red, respectively. TMD mutants of α1β2 are in light red. **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA).

GABA activates the GABAA receptor through binding in the ECD at the interface of the β+/α– subunits. Besides this orthosteric site, several allosteric binding sites have been established, of which the benzodiazepine site (BZ) in the ECD at the α+/γ– interface is the most well-known.38 More recently, a distinct binding site in the ECD at the α+/β– interface has been identified for the ligand CGS9895.39,40 In addition to binding sites in the ECD, several anesthetics and neurosteroids affect channel activity through binding in the TMD. Recent X-ray crystal structures and cryo-EM structures have shed light on the TM residues involved in binding.41,42

In order to determine the binding site for the PAM (±)-2, we performed mutagenesis on residues that have been implicated in binding of known modulators. For the first screen we selected α1(H129R)38 and α1(Y209Q)40,43 to probe the BZ-site, β2(Q88C) to probe the α+/β– site,39 and triple mutant α1(S297I)β2(N289I)γ2(S319I) to probe for anesthetic sites in the TMD.40,44 All three ECD mutants were potentiated to a similar extent as the WT receptor (mean 62 ± 6.1%). However, the triple TMD mutant was not affected by (±)-2 (mean 1.0 ± 3.0%) as shown in Figure 4C and Table S4. These results indicate that (±)-2 does not assert its potentiating affects through binding at the interfaces in the ECD but on one or more interfaces in the TMD.

To determine which specific interfaces are involved in binding in the TMD, we performed potentiation experiments for the single and double mutants of α1β2γ2, as well as the α1β2 subtype (Figure 4B). The mean potentiation in both mutants with single mutations in the α1 and γ2 subunits resembles that of the α1β2γ2 WT receptor. Only the single and double mutant receptors that contain a mutation in the β2 subunit demonstrate greatly reduced potentiation, suggesting involvement of the β2 subunit in binding. For the α1β2 subtype, greater variability among the mutants has been observed, but the same general trend appears. The β2(N289I) mutation is located in the TMD, close to the top of TM2, at the β+/α– interface (Figure 4A). This residue has been implicated in the binding of several anesthetics, such as etomidate, propofol, and loreclezole.40,45

We performed potentiation experiments on these GABAA mutants similarly as described in Figure 2; however, here we coapplied the 40 μM PAM with an EC10–15 dose of GABA. To verify the EC10–15 values of the constructed mutant receptors, we determined the full dose–response relationships and found EC50 values similar to those reported previously (Table S5).40,44

Having characterized lead compound (+)-2, we aimed to optimize the potency of this ligand family by way of exploring substitutions at N1, C3a, C5, and C8a. Derivatization of the pyrroloindoline scaffold was undertaken with enantioenriched compounds 2 and 6 (Scheme 2). For each of the analogues synthesized, both enantiomers were prepared for evaluation of their ability to modulate GABAA receptors; however, for simplicity, the chemistry is depicted on the (+) enantiomers of 2 and 6 in Scheme 2. From carbamate (+)-6, Pd-catalyzed deprotection of the Cbz group afforded the N1-H pyrroloindoline (+)-7. Derivatization of C3a was examined to interrogate the possibility of the C3a hydroxyl group acting as a hydrogen bond donor. Deoxyfluorination of (+)-6 using diethylaminosulfur trifluoride followed by carbamate reduction with Red-Al furnished tertiary fluoride (+)-9. Methylation of the C3a hydroxy group of (+)-2 under standard conditions gave C3a-methoxy pyrroloindoline (+)-10.

Scheme 2. Derivatization of the Pyrroloindoline Framework.

Recognizing that physostigmine (1) possesses oxidation at C5, we also sought to derivatize this position of the pyrroloindoline framework with both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents. Electrophilic aromatic substitution of (+)-2 with N-iodosuccinimide afforded aryl iodide (−)-11 (Scheme 2). Cu-catalyzed trifluoromethylation of the iodoarene gave (+)-12.46 Bromination was also feasible using N-bromosuccinimide to furnish (+)-13. From the aryl bromide, Cu-catalyzed methoxylation provided methoxy analogue (+)-14.47 Additionally, Buchwald–Hartwig coupling of aryl bromide (+)-13 gave morpholine (−)-15.48

We also sought to introduce structural variations on the C8a aryl group. Using 1-bromo-4-iodobenzene, Pd-catalyzed C2 arylation of protected tryptamine 4 gave an aryl bromide analogue that was advanced to pyrroloindoline (±)-16 (see Scheme S1 for synthetic details).

Functional evaluation of the series of pyrroloindoline derivatives was conducted using two-electrode voltage clamp electrophysiology as described earlier for (±)-2. General trends will be discussed first. Most of the derivatives do not demonstrate agonist behaviors, except for compounds (−)-11 and (+)-13, which only activated the receptor with very low efficacy (Figure 6A). Generally, all derivatives demonstrate a similar activity pattern for the two enantiomers as we have observed for (±)-2, with only the S,S-enantiomer demonstrating activity. One exception to this is the aryl bromide 16, for which both enantiomers show substantial potentiation. It is also worth noting that morpholines (+)-15 and (−)-15, and aryl iodide (+)-11 and (−)-11, have reversed signs for their optical rotations as compared to all other derivatives.

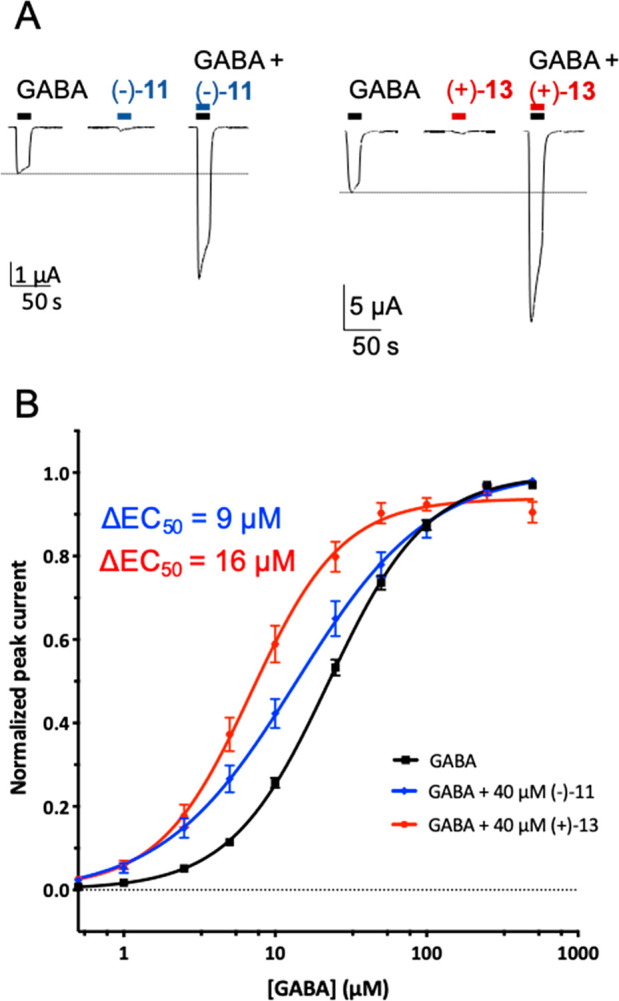

Figure 6.

Functional characterization of pyrroloindoline (−)-11 and (+)-13 at the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor. (A) Wave forms of the α1β2γ2 current responses from a GABA EC10 only dose, 40 μM (±)-11 or (+)-13 only dose, and coapplication of GABA EC10 and 40 μM PAM. (B) PAM-induced shift in GABA EC50. A 40 μM concentration of (−)-11 and (+)-13 was used here.

Changes at N1 resulted in decreased potentiation relative to the enantiomerically pure parent ligand (+)-2 (125 ± 15%), with the N1-protio compound (+)-7 and the N1-Cbz compound (+)-6 giving potentiation values of 41 ± 3.0% and 9.6 ± 5.2%, respectively (Figure 5A and Table S6). Substitution of the C3a hydroxyl with fluorine ((+)-9) gives similar potentiation (100 ± 11%) to (+)-2, whereas methylation of the hydroxyl group ((+)-10) results in a substantial reduction in activity (21 ± 3.0%).

Figure 5.

Functional effects of pyrroloindoline derivatives at the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor. (A) N1, C2, C3-substituted derivatives. (B) C5-substituted derivatives. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA).

Next, we looked at the C5-substituted derivatives (Figure 5B and Table S6). The presence of a methoxy ((+)-14) or morpholino ((+)-15) substituent at C5 drastically reduced the potentiation efficacy to 17 ± 3.2% and −4.8 ± 1.8%, respectively. Potentiation by trifluoromethyl compound (+)-12 resembled that of (+)-2 at 108 ± 9.5%. Surprisingly, introduction of a halogen (Br or I) at C5 greatly increased potentiation with a modulation of 213 ± 21% for (+)-13 and 231 ± 24% for (−)-11, respectively (Figure 5B and 6A). This structure–activity relationship could indicate the presence of a halogen bonding binding interaction. These two ligands appear to have the largest potentiation effects on the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor at 40 μΜ of all the derivatives evaluated here. Therefore, we attempted to determine a full dose–response relationship for these two PAMs; however, solubility problems at concentrations greater than 100 μΜ prevented this (Figure S2). Additionally, we determined the GABA ΔEC50 shift due to 40 μΜ (−)-11 or (+)-13 at the α1β2γ2 receptor; we observed a 9 μM and 16 μM shift for (−)-11- and (+)-13, respectively (Figure 6B and Table S2). These values are similar to that observed for (±)-2.

Comparing the different effects of C5 substitution and structural variations at the C8a aryl group, recall that methoxy analogue (+)-14 did not exhibit any PAM properties, nor did methoxyarene (±)-SI-5 (Table S5). However, bromide (+)-13 demonstrated increased PAM properties relative to (+)-2. Considering the spatial positioning of the bromine at C5, we asked whether a ligand with a 4-Br-Ph at C8a would also possess PAM properties. Indeed, both aryl bromides (+)-16 (98 ± 8.3%) and (−)-16 (155 ± 11%) showed comparable potency to (+)-2 (Figure 5B and Table S6). It is surprising that both enantiomers of 16 are active, and we hypothesize that the R,R-enantiomer (−)-16 might be able to bind in an “upside down” orientation, in which the bromine occupies the same position as the bromine of ligand (+)-13. Figure 7 depicts an overlay of the two chemical structures, (+)-13 and (−)-16, to illustrate this. (−)-16 is shown at a slightly rotated orientation (looking down C3a and C8a instead of C2) to mimic the orientation of (+)-13, which indeed resembles this structure. These results indicate that not only is the para-position of the C8a-phenyl substituent permissive to halide substitution, but it is possible that (−)-16, the R,R-enantiomer, is able to fit the binding pocket in the upside down orientation, unlike the other ligands tested in this study.

Figure 7.

Overlay of chemical structures of (+)-13 and (−)-16.

Conclusion

In this work, we described the synthesis of a series of pyrroloindoline compounds and functional evaluation for positive allosteric modulation at the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor. First, we characterized the lead positive allosteric modulator (±)-2, which has an EC50 of 110 μM and causes a 13 μΜ shift in GABA EC50. Second, we performed mutagenesis studies to elucidate the binding site of this PAM. We found that the TMD triple mutant α1(S297I)β2(N289I)γ2(S319I) completely lost sensitivity to (±)-2, while ECD mutants displayed no meaningful change. This strongly suggests that the binding site is located in the TMD at the top of TM2.

Next, we explored substitution of 2 at various positions to increase efficacy. Like the parent compound, most ligands demonstrated PAM properties only for the S,S-enantiomer. The most potent PAMs tested here contain a bromine or iodine at C5, (+)-13, and (−)-11 respectively. Ligand (±)-16 demonstrated increased potentiation efficacy relative to the parent ligand (±)-2 for both enantiomers. We suspect that the (−) enantiomer, which is generally inactive for other compounds, may be able to fit into the binding pocket in an upside-down orientation due to its 4-Br-Ph substitution at C2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alex Maolanon and Katie Chan for early synthesis efforts, as well as Chris B. Marotta and Kristina Daeffler for performing the preliminary Cys-loop screen. We are grateful to Scott Virgil and the Caltech Center for Catalysis and Chemical Synthesis for access to analytical equipment and assistance with performing preparative chiral HPLC and SFC resolutions. S.E.R. is a Heritage Medical Research Institute Investigator. Financial support from the NIH (S.E.R. R35GM118191-01) is gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- GABAA

γ-aminobutyric acid type A

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- pLGIC

pentameric ligand-gated ion channel

- BZ

benzodiazepine

- SEM

standard error of the mean.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00340.

Detailed experimental procedures, compound characterization data, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra (PDF)

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rudolph U.; Möhler H. GABAA Receptor Subtypes: Therapeutic Potential in Down Syndrome, Affective Disorders, Schizophrenia, and Autism. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 54, 483–507. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braat S.; Kooy R. The GABAA Receptor as a Therapeutic Target for Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Neuron 2015, 86 (5), 1119–1130. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens D. N.; King S. L.; Lambert J. J.; Belelli D.; Duka T. GABAA Receptor Subtype Involvement in Addictive Behaviour. Genes Brain Behav 2017, 16 (1), 149–184. 10.1111/gbb.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen R. W.; Sieghart W. International Union of Pharmacology. LXX. Subtypes of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid(A) Receptors: Classification on the Basis of Subunit Composition, Pharmacology, and Function. Update. Pharmacol. Rev. 2008, 60 (3), 243–260. 10.1124/pr.108.00505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley S. G.; Mody I. Extrasynaptic GABA(A) Receptors: Their Function in the CNS and Implications for Disease. Neuron 2012, 73 (1), 23–34. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M.; Nusser Z. Variations on an Inhibitory Theme: Phasic and Tonic Activation of GABA(A) Receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6 (3), 215–229. 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S.; Noviello C. M.; Teng J.; Walsh R. M.; Kim J. J.; Hibbs R. E. Structure of a Human Synaptic GABAA Receptor. Nature 2018, 559 (7712), 67–72. 10.1038/s41586-018-0255-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller P. S.; Smart T. G. Binding, Activation and Modulation of Cys-Loop Receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2010, 31 (4), 161–174. 10.1016/j.tips.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W. Allosteric Modulation of GABAA Receptors via Multiple Drug-Binding Sites. Adv. Pharmacol. 2015, 72, 53–96. 10.1016/bs.apha.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloos J.-M.; Ferreira V. Current Use of Benzodiazepines in Anxiety Disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2009, 22 (1), 90–95. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32831a473d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atack J. R. Anxioselective Compounds Acting at the GABAA Receptor Benzodiazepine Binding Site. Curr. Drug Targets: CNS Neurol. Disord. 2003, 2 (4), 213–232. 10.2174/1568007033482841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin C. E.; Kaye A. M.; Bueno F. R.; Kaye A. D. Benzodiazepine Pharmacology and Central Nervous System–Mediated Effects. Ochsner J. 2013, 13 (2), 214–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama N.; Ritter B.; Neubert A. 2-Arylpyrazolo[4,3-c]Quinolin-3-Ones: Novel Agonist, Partial Agonist, and Antagonist of Benzodiazepines. J. Med. Chem. 1982, 25 (4), 337–339. 10.1021/jm00346a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D. Pharmacology of the Pyrazolo-Type Compounds: Agonist, Antagonist and Inverse Agonist Actions. Physiol. Behav. 1987, 41 (3), 241–245. 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90360-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackaby W. P.; Atack J. R.; Bromidge F.; Lewis R.; Russell M.; Smith A.; Wafford K.; McKernan R. M.; Street L. J.; Castro J. L.. Pyrazolopyridinones as Functionally Selective GABAA Ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15 ( (22), ), 4998–5002. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone X.; Siebert D. C. B. C.; Bampali K.; Varagic Z.; Treven M.; Rehman S.; Pyszkowski J.; Holzinger R.; Steudle F.; Scholze P.; Mihovilovic M. D.; Schnürch M.; Ernst M. Molecular Tools for GABAA Receptors: High Affinity Ligands for Β1-Containing Subtypes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7 (1), 5674. 10.1038/s41598-017-05757-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treven M.; Siebert D. C. B. C.; Holzinger R.; Bampali K.; Fabjan J.; Varagic Z.; Wimmer L.; Steudle F.; Scholze P.; Schnürch M.; Mihovilovic M. D.; Ernst M. Towards Functional Selectivity for Α6β3γ2 GABAA Receptors: A Series of Novel Pyrazoloquinolinones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175 (3), 419–428. 10.1111/bph.14087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolognesi M.; Andrisano V.; Bartolini M.; Minarini A.; Rosini M.; Tumiatti V.; Melchiorre C. Hexahydrochromeno[4,3-b]Pyrrole Derivatives as Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44 (1), 105–109. 10.1021/jm000991r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby H. I.Gastric Emptying. In Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences; Elsevier, 2017. 10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.64921-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiroma L. O.; Costa V. P.. 56 - Parasympathomimetics. In Glaucoma, 2nd ed.; Shaarawy T. M., Sherwood M. B., Hitchings R. A., Crowston J. G., Eds.; W.B. Saunders, 2015; pp 577–582. [Google Scholar]

- Militante J.; Ma B.-W. W.; Akk G.; Steinbach J. H. Activation and Block of the Adult Muscle-Type Nicotinic Receptor by Physostigmine: Single-Channel Studies. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74 (3), 764–776. 10.1124/mol.108.047134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda A. K.; Kimm T.; Cohen J. B. Physostigmine and Galanthamine Bind in the Presence of Agonist at the Canonical and Noncanonical Subunit Interfaces of a Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33 (2), 485–494. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3483-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X.; McCollum M. M.; Germann A. L.; Akk G.; Steinbach J. H. The E Loop of the Transmitter Binding Site Is a Key Determinant of the Modulatory Effects of Physostigmine on Neuronal Nicotinic Α4β2 Receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2017, 91 (2), 100–109. 10.1124/mol.116.106484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repka L. M.; Ni J.; Reisman S. E. Enantioselective Synthesis of Pyrroloindolines by a Formal [3 + 2] Cycloaddition Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (41), 14418–14420. 10.1021/ja107328g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer M. E.; Chuang K. V.; Reisman S. E. Copper-Catalyzed Diastereoselective Arylation of Tryptophan Derivatives: Total Synthesis of (+)-Naseseazines A and B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (15), 5557–5560. 10.1021/ja4023557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Reisman S. E. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (−)-Lansai B and (+)-Nocardioazines A and B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53 (24), 6206–6210. 10.1002/anie.201402571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeffler K. N.-M.Functional Evaluation of Noncovalent Interactions in Neuroreceptors and Progress Toward the Expansion of Unnatural Amino Acid Methodology. Dissertation (Ph.D.), California Institute of Technology, 2014. 10.7907/ST7S-DB65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta C. B.Structure-Function Studies of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Using Selective Agonists and Positive Allosteric Modulators. Dissertation (Ph.D.), California Institute of Technology, 2015. 10.7907/Z9V122Q9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Rodríguez J.; Albericio F.; Lavilla R. Postsynthetic Modification of Peptides: Chemoselective C-Arylation of Tryptophan Residues. Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16 (4), 1124–1127. 10.1002/chem.200902676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repka L. M.Enantioselective Synthesis of Pyrroloindolines and Tryptophan Derivatives by an Asymmetric Protonation Reaction. Dissertation (Ph.D.), California Institute of Technology, 2014. 10.7907/Y8MS-J286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry E. C.; Rono L. J.; Hale M. E.; Matsuura R.; Knowles R. R. Enantioselective Synthesis of Pyrroloindolines via Noncovalent Stabilization of Indole Radical Cations and Applications to the Synthesis of Alkaloid Natural Products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (9), 3394–3402. 10.1021/jacs.7b13616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden S. P.; Depew K. M.; Danishefsky S. J. Stereoselective Total Syntheses of Amauromine and 5-N-Acetylardeemin. A Concise Route to the Family of “Reverse-Prenylated” Hexahydropyrroloindole Alkaloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116 (24), 11143–11144. 10.1021/ja00103a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse T.; Baran P. S. Total Synthesis of (±)-Psychotrimine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130 (33), 10886–10887. 10.1021/ja8042307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T.; Seki T.; Yakura T.; Takeuchi Y. Useful Procedures for Fluorocyclization of Tryptamine and Tryptophol Derivatives to 3a-Fluoropyrrolo[2,3-b]Indoles and 3a-Fluorofuro[2,3-b]Indoles. J. Fluorine Chem. 2014, 165, 7–13. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2014.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolundzic F.; Noshi M. N.; Tjandra M.; Movassaghi M.; Miller S. J. Chemoselective and Enantioselective Oxidation of Indoles Employing Aspartyl Peptide Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (23), 9104–9111. 10.1021/ja202706g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baburin I.; Khom S.; Timin E.; Hohaus A.; Sieghart W.; Hering S. Estimating the Efficiency of Benzodiazepines on GABAA Receptors Comprising Γ1 or Γ2 Subunits. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 155 (3), 424–433. 10.1038/bjp.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson S. M.; Czajkowski C. Structural Mechanisms Underlying Benzodiazepine Modulation of the GABA(A) Receptor. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28 (13), 3490–3499. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5727-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland H.; Lüddens H.; Seeburg P. A Single Histidine in GABAA Receptors Is Essential for Benzodiazepine Agonist Binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267 (3), 1426–1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramerstorfer J.; Furtmüller R.; Sarto-Jackson I.; Varagic Z.; Sieghart W.; Ernst M. The GABAA Receptor Α+β– Interface: A Novel Target for Subtype Selective Drugs. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31 (3), 870–877. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5012-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldifassi M. C.; Baur R.; Sigel E. Molecular Mode of Action of CGS 9895 at Α1 Β2 Γ2 GABAA Receptors. J. Neurochem. 2016, 138 (5), 722–730. 10.1111/jnc.13711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverty D.; Thomas P.; Field M.; Andersen O. J.; Gold M. G.; Biggin P. C.; Gielen M.; Smart T. G. Crystal Structures of a GABAA-Receptor Chimera Reveal New Endogenous Neurosteroid-Binding Sites. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24 (11), 977. 10.1038/nsmb.3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masiulis S.; Desai R.; Uchański T.; Serna Martin I.; Laverty D.; Karia D.; Malinauskas T.; Zivanov J.; Pardon E.; Kotecha A.; Steyaert J.; Miller K. W.; Aricescu A. GABAA Receptor Signalling Mechanisms Revealed by Structural Pharmacology. Nature 2019, 565 (7740), 454–459. 10.1038/s41586-018-0832-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhr A.; Schaerer M.; Baur R.; Sigel E. Residues at Positions 206 and 209 of the Alpha1 Subunit of Gamma-Aminobutyric AcidA Receptors Influence Affinities for Benzodiazepine Binding Site Ligands. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997, 52 (4), 676–682. 10.1124/mol.52.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters R.; Hadley S.; Morris K.; Amin J. Benzodiazepines Act on GABAA Receptors via Two Distinct and Separable Mechanisms. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3 (12), 1274–1281. 10.1038/81800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingrove P. B.; Wafford K. A.; Bain C.; Whiting P. J.. The Modulatory Action of Loreclezole at the Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptor Is Determined by a Single Amino Acid in the Beta 2 and Beta 3 Subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994, 91 ( (10), ), 4569–4573. 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonda Z.; Kovács S.; Wéber C.; Gáti T.; Mészáros A.; Kotschy A.; Novák Z. Efficient Copper-Catalyzed Trifluoromethylation of Aromatic and Heteroaromatic Iodides: The Beneficial Anchoring Effect of Borates. Org. Lett. 2014, 16 (16), 4268–4271. 10.1021/ol501967c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashimori A.; Bachand B.; Calter M. A.; Govek S. P.; Overman L. E.; Poon D. J. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Quaternary Carbon Centers. Exploratory Studies of Intramolecular Heck Reactions of (Z)-α,β-Unsaturated Anilides and Mechanistic Investigations of Asymmetric Heck Reactions Proceeding via Neutral Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120 (26), 6488–6499. 10.1021/ja980787h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garlapati R.; Pottabathini N.; Gurram V.; Chaudhary A. B.; Chunduri V. R.; Patro B. Pd-Catalyzed Amination of 6-Halo-2-Cyclopropyl-3-(Pyridyl-3-Ylmethyl) Quinazolin-4(3H)-One. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53 (38), 5162–5166. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.07.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.