Abstract

A bivalent compound 1a featuring both a mu opioid receptor (MOR) and a CXCR4 antagonist pharmacophore (naltrexone and IT1t) was designed and synthesized. Further binding and functional studies demonstrated 1a acting as a MOR and a CXCR4 dual antagonist with reasonable binding affinities at both receptors. Furthermore, compound 1a seemed more effective than a combination of IT1t and naltrexone in inhibiting HIV entry at the presence of morphine. Additional molecular modeling results suggested that 1a may bind with the putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer to induce its anti-HIV activity. Collectively, bivalent ligand 1a may serve as a promising lead to develop chemical probes targeting the putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer in comprehending opioid exacerbated HIV-1 invasion.

Keywords: mu opioid receptor, chemokine receptor CXCR4, bivalent ligand, HIV-1 entry inhibition

Drug abuse and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) remain two interrelated epidemics that threat human health with high treatment costs and various related clinical complications. As one type of major abused substances, opioids primarily exert their abusive and addictive abilities through modulating the mu opioid receptor (MOR).1 Meanwhile, mounting studies have shown that chronic exposure of opioids could pose negative impact on the immune system via immunomodulation regulated via actions on the MOR.2 Moreover, opioids appear to exacerbate the central nervous system (CNS) complications of human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) infection.2,3 Even in the advent of combined antiretroviral therapy (ART), opioid coexposure may still cause greater neurologic and cognitive deficits. Although opioid substitution therapy (OST) has tackled this issue in some degree, the overall therapeutic effect is far from satisfactory due to potential drug–drug interactions between substituted opioids and antiretroviral agents.4 Therefore, new approaches aiming to treat opioid abuse and AIDS comorbidities are still highly desirable.

It is perceived that opioids may accelerate HIV-1 infection by up-regulating chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR4, two viral entry coreceptors, in immune and nonimmune cells.5,6 More particularly, studies have shown that MOR agonists, e.g. DAMGO and morphine, significantly enhance CXCR4 expression in lymphoblasts and monocytes,7,8 which supported potentially functional crosstalk between the MOR and CXCR4. In fact, accumulating evidence has revealed that these two G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) may undergo crosstalk via heterodimerization.9,10 As shown in previous studies, bivalent ligands that are able to interact with both receptors simultaneously may help to elucidate the underlying mechanism of GPCR dimerization11,12 as well as serve as therapeutic tools in the treatment of related diseases.13,14 Despite these studies showing the potential on modulation of MOR and CXCR4 dimerization, a bivalent ligand that possesses promising pharmacological and therapeutic effects by targeting this mechanism has never been reported. In this regard, it would be invaluable to develop bivalent ligands targeting putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimers and investigate their role in deleterious opioid and HIV interactions, which can exacerbate the infection, its pathologic consequences, and progression to AIDS. Our preliminary explorations revealed that a bivalent compound featuring both a MOR and a CXCR4 antagonist pharmacophore may preserve acceptable binding affinities and functional activities at both respective receptors.15 In this work, we report our most recent progress on development of a bivalent ligand targeting the putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer with the potential to effectively inhibit opioid enhanced HIV-1 invasion.

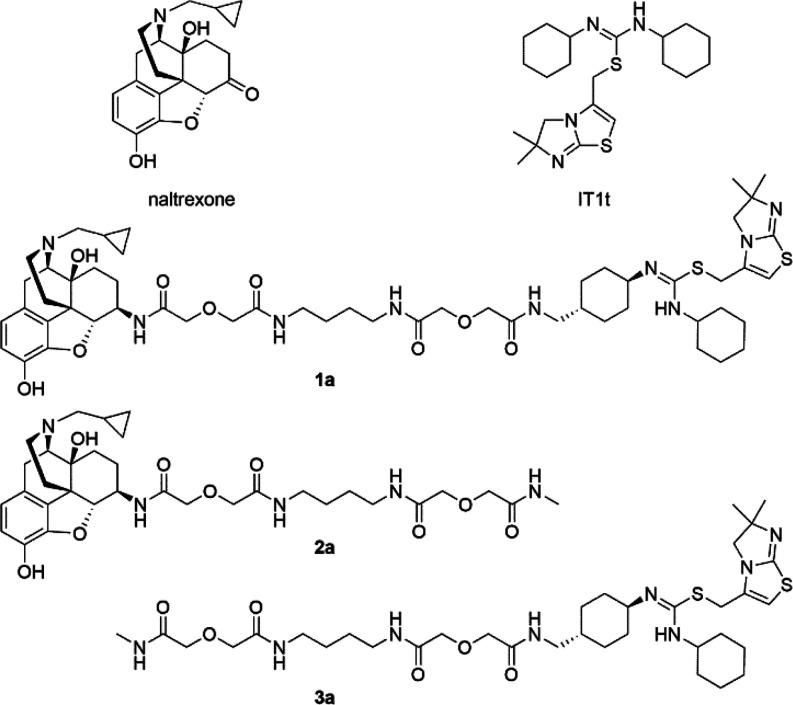

In the rational design of a bivalent ligand, three factors should be considered, i.e. selection of pharmacophores, choices of suitable attachment points of the spacer, and optimal length and chemical composition of the spacers.16 In our case, naltrexone (Figure 1) was adopted as the MOR antagonist pharmacophore considering its previously successful application in studies of dimerization of opioid receptors,17,18 and its desirable effects in treating opioid addiction in clinic.19,20 Based on previous bivalent ligand studies, introduction different spacers to the C6-position of naltrexone appeared to not significantly influence its MOR affinity.14,15,21,22 Moreover, the docking pose of naltrexone in the inactive MOR indicated that the C6-position of naltrexone pointed toward the extracellular end of the transmembrane helix 5 (TM5) and TM6 (Figure 2a). Taken together, the C6-position of naltrexone was selected as the attachment point once transforming its carbonyl group to the 6β-amino group (Figures 2c).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of naltrexone, IT1t, designed bivalent ligand 1a, and monovalent controls 2a and 3a.

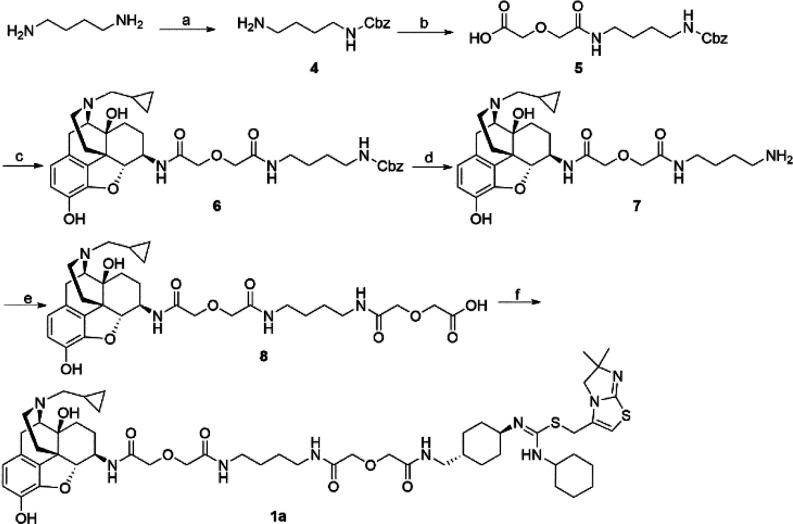

Figure 2.

Designing components of the bivalent ligand 1a: (a) Docking pose of naltrexone within the MOR from docking study (PDB ID: 4DKL(28)); (b) binding mode of IT1t within the CXCR4 from its crystal structure (PDB ID: 3ODU(23)); (c) attachment points.

IT1t (Figure 1) was adopted as the CXCR4 antagonist pharmacophore due to the fact that it is the only ligand cocrystallized with the CXCR4 at present.23 From the binding mode of IT1t in CXCR4 (Figures 2b), one of the cyclohexyl groups attached to the nitrogen atoms of the symmetric isothiourea group pointed upward and toward the extracellular end of TMs 1, 2, and 3, making it a suitable candidate to connect with the spacer. The 4′ position on the cyclohexyl ring was chosen as the attachment point in order to avoid complex stereochemistry by maintaining relative molecular symmetry (Figures 2c). Since the coupling reaction between the carboxylic acid and amine can be easily accomplished, an aminomethyl group was then chosen as the extension group on the cyclohexyl ring to connect IT1t moiety with the spacer. Meanwhile, the trans-conformation at 4′ position was chosen as the cyclohexyl ring would adopt a chair conformation to provide an upward orientation from the receptor binding pocket to ensure the least interference with receptor binding.

Numerous reports have pointed out that the spacer length of a bivalent ligand played critical roles in the binding to GPCR dimers while a spacer with a length between 16 and 22 atoms might be optimal for binding affinities.24,25 In our current study, we incorporated an 18-atom spacer, two atoms shorter than our previously reported one.15 Meanwhile, to complementarily investigate how the spacer length affects activity, another bivalent ligand S1b bearing a longer spacer relative to the previously reported one was also synthesized. Aiming to keep good physicochemical properties such as favorable rigidity, high stability, and low toxicity,13,26,27 a spacer with one alkyldiamine moiety and two diglycolic units was employed (Figure 2c). In addition, their corresponding monovalent ligand controls for both naltrexone (2a and S2b) and IT1t (3a and S3b) pharmacophores were also synthesized for comparison purposes (Figures 1 and S1).

Following our reported procedure,15 the important intermediate aminomethyl-substituted IT1t (Table S2) was obtained with an acceptable yield through eight steps. The synthetic route of bivalent ligand 1a is depicted in Scheme 1. Monoprotected diamine 4 was treated with diglycolic anhydride to form 5. Next, 5 was coupled with prepared 6β-naltrexamine29 using EDCI/HOBt method to afford 6, which was then subjected to hydrogenation to give amine 7. The coupling reaction of 7 and diglycolic anhydride was accomplished to produce 8 with good yield. Finally, 8 and aminomethyl-substituted IT1t were coupled via EDCI/HOBt method to form the bivalent ligand 1a. The monovalent controls 2a and 3a were also synthesized following previously described procedure.15 By adopting similar synthetic routes, bivalent ligand S1b (Scheme S1) and its corresponding monovalent controls S2b and S3b were prepared accordingly.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route of Bivalent Ligand 1a.

Reagents and conditions: (a) CbzCl, CH2Cl2, MeOH; (b) diglycolic anhydride, THF; (c) 6β-naltrexamine, EDCI, HOBt, TEA, DMF; (d) H2, MeOH, Pd/C, 60 psi; (e) diglycolic anhydride, DMF; (f) aminomethyl-substituted IT1t, EDCI, HOBt, TEA, DMF.

All ligands were first subjected to their binding and functional property tests on the corresponding receptors. From the binding and functional assay results conducted in MOR-CHO cells (Tables 1 and S1), all tested ligands maintained their recognition at the MOR, which supported our original design. The binding affinity at the MOR was considerably improved by either decreasing or increasing linker length as seen for bivalent compounds 1a (Ki = 3.8 ± 0.17 nM) and S1b (Ki = 2.92 ± 0.28 nM) when compared to our previously reported bivalent ligand (Ki = 25.4 ± 3.00 nM),15 while similar binding affinities of monovalent controls 2a and S2b and parent pharmacophore naltrexone indicated that induction of spacers appeared to not significantly interfere with MOR binding. Meanwhile, based on [35S]-GTPγS functional assay results, all tested ligands maintained single-digit to double-digit nanomolar potency and showed no significant agonism compared to the full agonist DAMGO, which was expected based on their design as antagonists. The calcium mobilization assay results showed that all tested ligands acted as potent antagonists, albeit being less potent than the parent antagonist naltrexone. In all, these promising results suggested that our designed bivalent ligands might possess potential to block the effect elicited by morphine to potentiate HIV entry inhibition.

Table 1. MOR Radioligand Binding Assay, [35S]-GTPγS Functional Assay, and Calcium Mobilization Assay Results of Bivalent Ligand 1a and MOR Monovalent Control 2aa.

| [3H]NLX binding | MOR [35S]-GTPγS binding |

Ca2+ flux | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM) | % Emax of DAMGO | IC50 (nM) |

| NTXb | 0.4 ± 0.1 | ND | 7.1 ± 0.9 | 8.9 ± 0.9 |

| 1a | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 50.0 ± 15.0 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 30.5 ± 8.6 |

| 2a | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 12.3 ± 0.9 | 254.0 ± 23.0 |

The values are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Membranes for radioligand binding assays were prepared from mMOR-CHO cells. Calcium mobilization assay was performed on hMOR-CHO cells. NTX, Naltrexone. ND, not determined.

Data adopted from ref (15).

All the synthesized compounds bearing the IT1t pharmacophore were then tested for binding affinity and functional activity at CXCR4 (Tables 2 and S2). In the antibody binding assay with CXCR4-CHO cells, bivalent ligand 1a possessed substantially reduced binding affinity over CXCR4 (IC50 = 3.6 ± 0.3 μM) while it was about 5 times more potent when compared to our previously reported bivalent ligand (IC50 = 17.2 ± 2.7 μM).15 A more significant reduction on the binding affinity of monovalent control 3a than 1a suggested that the spacer was not well tolerated in binding to CXCR4. Meanwhile, we also observed that when only an aminomethyl group was introduced onto the 4′-position of the cyclohexyl ring, the resulting intermediate aminomethyl-substituted IT1t was equipotent to IT1t with an IC50 value of 5.65 ± 0.69 nM (Table S3). These observations revealed that the bulky spacer was likely to interfere with receptor binding and recognition resulting in the binding affinity reduction over the CXCR4 though a relatively smaller substitution seemed tolerable. In calcium mobilization assays with HOS-CXCR4 cells, none of tested compounds showed noticeable agonism and bivalent compound 1a exhibited moderate inhibitory activity against SDF-1induced calcium flux (IC50 = 8.3 ± 2.3 μM). Meanwhile, a similar trend of potency was found when comparing the monovalent control to the bivalent compound (3a vs 1a). This observation seemed in line with the antibody binding affinity results. In addition, the results as seen in Table S2 demonstrated even greater reduction of binding affinity for both bivalent compound S1b and monovalent control S3b having 20-atom spacers. This further corroborated our speculation that the incorporation of bulky spacer was deleterious for the recognition at CXCR4. Nevertheless, the seemingly reasonable observations yet somehow lower potency at CXCR4 provided opportunities to further optimize our molecular design.

Table 2. CXCR4 Antibody Binding Assay and Calcium Mobilization Assay Results of Bivalent Ligand 1a and CXCR4 Monovalent Control 3aa.

| antibody binding | Ca2+ flux | |

|---|---|---|

| compd | IC50 (nM) | IC50 (nM) |

| IT1tb | 7.40 ± 3.80 | 32.5 ± 8.8 |

| 1a | 3600 ± 300 | 8300 ± 2300 |

| 3a | 69000 ± 24000 | 53000 ± 6600 |

The values are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. The CXCR4 antibody-binding assay was performed on CHO-CXCR4 cells. The antagonist calcium assay was conducted on HOS-CXCR4 cells.

Data adopted from ref (15).

Considering that bivalent ligand 1a manifested improved binding affinity and functional activity at the MOR while maintaining reasonable recognition at the CXCR4, it was advanced to be evaluated in HIV-1 infectious assays. As critical viral proteins in the HIV life cycle, the envelope protein gp120 and the viral capsid protein p24 are commonly used as HIV detection markers.30 Thus, we chose reverse transcriptase (RT) and protein Tat as markers in this assay because they are key mediators in the viral life cycle to indicate HIV entry or replication.31

In order to measure the ability of the compounds to inhibit HIV entry, reverse RT activity assay was conducted in GHOST CXCR4 cells. Meanwhile, XTT assays for cell viability and cellular toxicity were also applied in the same cell line. The parent pharmacophore IT1t was adopted as a positive control. As seen in the assay results (Table 3), bivalent ligand 1a potently inhibited HIV entry with submicromolar activity (IC50 = 0.96 ± 0.09 μM) and approximately 150-fold more potent than that of the monovalent control 3a. It was postulated that a more flexible spacer in 3a might alter the binding pose of the pharmacophore and subsequently interfere receptor recognition more significantly. The cytotoxicity results suggested that 1a was not toxic at its IC50 value. Taken together, the relatively high therapeutic index (TI) value of bivalent ligand 1a suggested its potential therapeutic effect in blocking HIV-1.

Table 3. Inhibition of HIV-1IIIB and Cytotoxicity in GHOST CXCR4 Cellsa.

| compd | EC50 (μM) | TC50 (μM) | TI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 0.96 ± 0.09 | 153.3 ± 2.5 | 160 |

| 3a | 144.5 ± 24.7 | 553.4 ± 10.9 | 3.8 |

| IT1t | 0.022 ± 0.0006 | >1.0 | >45 |

EC50: concentration of compound required to achieve 50% inhibition of virus replication in GHOST CXCR4 cells and determined by reverse transcriptase activity assay. TC50: concentration of compound required to achieve 50% reduction in GHOST CXCR4 cells and determined by XTT assay. The values are the mean ± standard deviation (SD). TI: therapeutic index, ratios of TC50/EC50.

Bivalent ligand 1a was then subject to Tat LTR-luciferase assay to measure its inhibitory activity against the HIV regulatory protein Tat. This assay was conducted in X4-tropic virus HIV-1IIIB infected reporter cell line TZM-bl.32 Dose response studies indicated that compound 1a was able to inhibit HIV-1 entry with an IC50 value of 300 nM and inhibit viral entry 100% at the maximum concentration of 30 μM, which was relatively less potent compared to the parent pharmacophore IT1t (IC50 = 164.4 ± 38.8 nM).

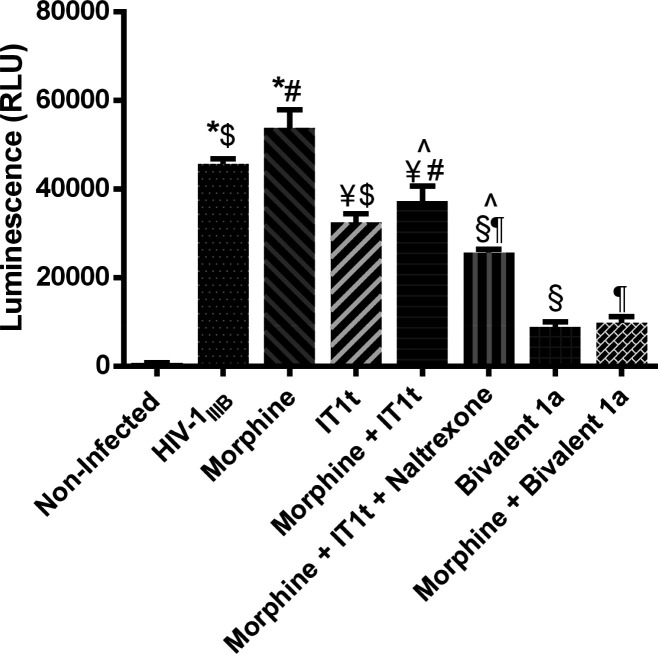

We further examined the viral entry inhibitory effects of the bivalent ligands with that of a mixture of the two pharmacophores naltrexone and IT1t with and without the presence of morphine. As shown in Figure 3, relative expression of Tat was significantly increased in TZM-bl cells after infection with HIV-1IIIB alone while even more increased in the presence of morphine, indicating the enhancement of viral invasion by morphine. On the exposure of IT1t, the amount of Tat protein was significantly reduced compared to the previous two conditions. Although it is unclear how the addition of morphine attenuated the ability of IT1t to inhibit viral entry, the finding was consistent with our previous results on bivalent MOR-CCR5 compounds indicating that morphine decreased the anti-HIV activity of the CCR5 coreceptor antagonist maraviroc.14,21,22 When naltrexone was added together with IT1t in the presence of morphine, decreasing viral entry was observed, which can be explained by naltrexone blocking the effects elicited by morphine. More importantly, bivalent ligand 1a alone was significantly effective in inhibiting viral entry, and this effect was not abolished by the presence of morphine, indicating the potential of 1a as an adjunctive therapy with IT1t in individuals who are subject to high levels of opiate exposure.

Figure 3.

Viral inhibition effects of bivalent compound 1a with coexposure to morphine. HIV-1IIIB infectivity in TZM-bl was determined based on the relative amount of Tat protein expressed by the virus using a luciferase-based assay. Morphine, 500 nM; IT1t, 60 nM (see Figure S5 for dose–response curve); Bivalent compound 1a,1000 nM; Naltrexone, 1500 nM.14 Values are from one experiment run at 3 days postinfection. All compounds or their combinations applied have been studied for their dose responses. Data are presented as mean% inhibition values ± SD [*p = > 0.05 X4 virus vs morphine; $p < 0.05 X4 virus vs IT1t; #p < 0.05 morphine vs morphine + IT1t; ¥p > 0.05 morphine + IT1t vs IT1t; p̂ < 0.05 M + I vs M + I + NTX; ¶p < 0.05 M + I + NTX vs Bivalent 1a + M; §p < 0.05 M + I + NTX vs Bivalent 1a].

As one of HIV entry coreceptors, CXCR4 is to bind with the V3 loop of glycoprotein subunit gp120 to facilitate viral entry in the first step of HIV life cycle.33,34 In addition, morphine exposure is suggested to up-regulate the expression of CXCR4 in human host cells,8 leading to more entry sites for viral entry. Based on this evidence, we speculated that our bivalent ligand 1a bearing both a MOR and a CXCR4 antagonist pharmacophore might simultaneously block MOR activation elicited by morphine as well as inhibit CXCR4 binding with gp120 to contribute its significant HIV entry inhibition. It is worth noting that only one concentration of IT1t (60 nM) was utilized as a positive control in this study. Thus, we may need to be more prudent to conclude that bivalent ligand 1a would be more potent in viral inhibition compared to even higher concentrations of IT1t in the presence of morphine. To summarize, these results supported our hypothesis that a rationally designed bivalent ligand may effectively block HIV-1 enhanced invasion by morphine by targeting the putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer.

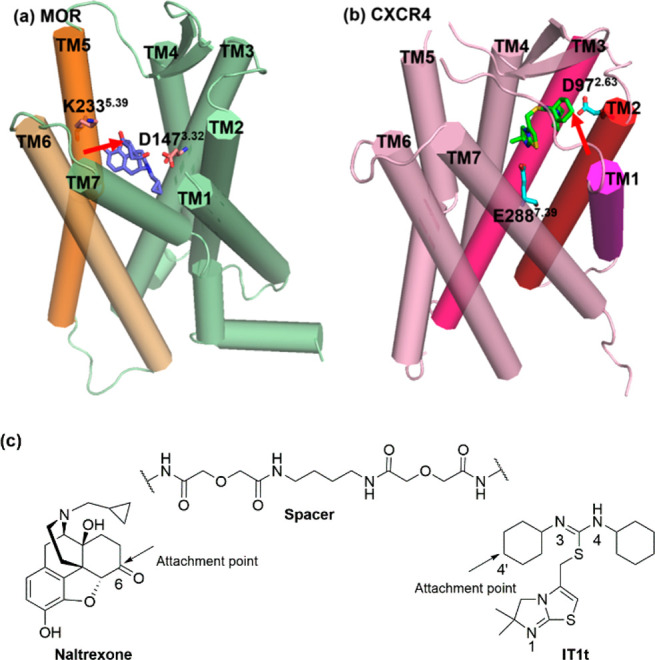

Further molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was conducted to help understand the interaction between bivalent ligand 1a and the putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer and explore a plausible mechanism of action in blocking HIV-1 invasion. (For details of computational studies, please refer to the Supporting Information.) The binding mode of the MOR-CXCR4_1a complex after 100 ns MD simulations and the crystal structure of the CXCR4 complexing with IT1t (CXCR4_IT1t) and the docking pose of the MOR complexing with naltrexone (MOR_naltrexone) after energy minimization are displayed in Figures 4 and S4.

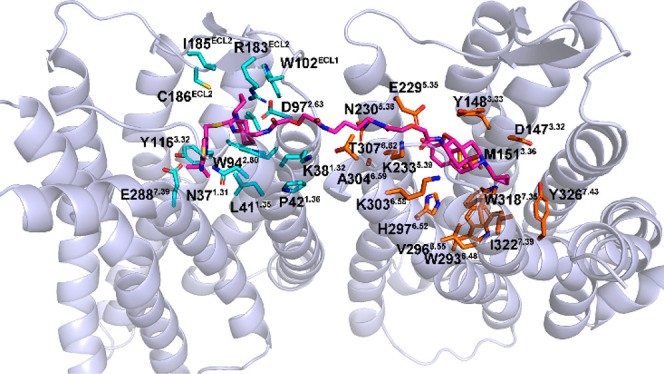

Figure 4.

Binding mode of MOR-CXCR4_1a complex after 100 ns MD simulation. Heterodimer MOR-CXCR4 is shown as a cartoon model in light-blue. Compound 1a is shown as stick and sphere models in magentas. Key residues of the CXCR4 and MOR are shown as stick models in cyan and orange, respectively.

In the MOR-CXCR4_1a complex, the CXCR4 pharmacophore IT1t formed similar interactions compared to that of IT1t in the crystal structure of CXCR4 (Figures 4 and S4a). The most significant difference is that, due to the spacer connected with one cyclohexyl group next to the N3 nitrogen atom of the isothiourea group, the symmetrical isothiourea groups of the CXCR4 pharmacophore IT1t may not be able to flip as IT1t in the CXCR4. Hence, two interactions, an ionic interaction with D972.63 (superscript numbers follow the Ballesteros–Weinstein numbering method for GPCRs35) and a polar interaction with C186ECL2 barely formed for 1a at the same time while these two interactions did exist in CXCR4_IT1t complex (see the Supporting Information). This may provide a putative explanation to the lower CXCR4 binding affinity of compound 1a relative to IT1t.

Meanwhile, the MOR pharmacophore naltrexone portion in compound 1a also formed similar interactions with the MOR to that of naltrexone in the MOR_naltrexone complex (Figures 4 and S4b). However, due to the spacer linked at the C-6 position of the MOR pharmacophore naltrexone, it can be observed that the MOR pharmacophore naltrexone shifted in some degree from its original binding position when compared with the docking pose of naltrexone in the MOR (Figure S4b). This may be further supported by the distance analyses shown in Table S4. Consequently, the binding affinity of compound 1a at the MOR was slightly lower than that of naltrexone.

As mentioned above, CXCR4 has been identified as one of the critical coreceptors required for HIV-1 entry.34 It has been suggested that ECL1 and ECL2 of CXCR4 may interact with the V3 loop of gp120 and further induce HIV attachment to the host cell membrane.36,37 Particularly, the residues, D182ECL2, R183ECL2, Y184ECL2, and D187ECL2, located at ECL2 of CXCR4 may be involved in such an interaction.38 The CXCR4 pharmacophore IT1t in the bivalent ligand 1a similarly formed hydrophobic interactions with residues, R183ECL2, I185ECL2, and C186ECL2, from ECL2 of CXCR4. Therefore, potentially bivalent ligand 1a may prevent HIV entry through inhibiting the interaction between the V3 loop of gp120 and the ECL2 of CXCR4. Moreover, as bivalent ligand 1a acted as a potent MOR antagonist (Table 1), the CXCR4 enhancement elicited by morphine in human host cells may also be blocked due to the fact that the MOR pharmacophore naltrexone may effectively compete with morphine for the same binding pocket in the MOR.8,39,40 This further conferred its significant HIV entry inhibitory activity even in the presence of morphine.

In conclusion, targeting the putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer may be a plausible approach to treat opioid abuse and HIV-1 comorbidities. Bivalent ligand 1a has proven to be a MOR and CXCR4 dual antagonist with reasonable binding affinities at both receptors. Further anti-HIV studies indicated that 1a potently inhibited HIV-1 entry with low cytotoxicity. More importantly, it seemed potent in HIV entry inhibition with the presence of morphine through inhibiting both the MOR and CXCR4. Molecular modeling results suggested that 1a may bind with the putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer in an acceptable manner. Moreover, the binding of CXCR4 pharmacophore IT1t with the specific domain of CXCR4 that involved in gp120 and CXCR4 recognition revealed that 1a may block the interaction between gp120 and CXCR4 to further prevent HIV entry. We also recognized the possibly intrinsic shortcomings in our original molecular design considering the low binding affinity of the first series of bivalent ligands at the CXCR4. Thus, a more comprehensive study is ongoing to further optimize our molecular design. As a proof-of-concept, bivalent ligand 1a appears to serve as a promising lead to develop more potent chemical probes in order to investigate the interactions between the MOR and CXCR4 in opioid exacerbated HIV-1 invasion.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AIDS

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- OST

opioid substitution therapy

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- MOR

mu opioid receptor

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- TI

therapeutic index

- CNS

central nervous system

- RT

reverse transcriptase

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00444.

Synthetic procedures, analytical data of final compounds, biological results of compounds S1b–3b and aminomethyl-substituted IT1t, biological protocols, modeling procedure and results (PDF)

Author Contributions

Y. Zhang conceived and oversaw the project and finalized the manuscript. H. Ma and H. Wang drafted the manuscript. B. Reinecke, G. Kang, H. Ma, and R. Gunta conducted the chemical synthesis, M. Li and Y. Zheng conducted the calcium flux assays, and H. Wang finished the docking studies under the supervision of Y. Zhang. N. Nassehi conducted radioligand binding assays under the supervision of D. E. Selley. H. Zhang conducted antibody binding assays under the supervision of J. An. B. Reinecke and V. Barreto-de-Souza conducted the anti-HIV assays under the supervision of K. Hauser.

HOS.CXCR-4 (Dr. Nathaniel Landau) was obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program. We thank funding from the NIMH Translational Research in NeuroHIV and Mental Health Pilot Grant R25MH080661 and the NIDA grant R01DA044855 and DA024022 (Y. Z.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Fiellin D. A.; Kleber H.; Trumble-Hejduk J. G.; McLellan A. T.; Kosten T. R. Consensus statement on office-based treatment of opioid dependence using buprenorphine. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2004, 27, 153–159. 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser K. F.; Fitting S.; Dever S. M.; Podhaizer E. M.; Knapp P. E. Opiate drug use and the pathophysiology of neuroAIDS. Curr. HIV Res. 2012, 10, 435–452. 10.2174/157016212802138779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser K. F.; El-Hage N.; Buch S.; Berger J. R.; Tyor W. R.; Nath A.; Bruce-Keller A. J.; Knapp P. E. Molecular targets of opiate drug abuse in neuroAIDS. Neurotoxic. Res. 2005, 8, 63–80. 10.1007/BF03033820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Rao P. S.; Earla R.; Kumar A. Drug-drug interactions between anti-retroviral therapies and drugs of abuse in HIV systems. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2015, 11, 343–355. 10.1517/17425255.2015.996546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M.; Zheng J.; Okamoto S.; Gendelman H. E.; Lipton S. A. HIV-1 infection and AIDS: consequences for the central nervous system. Cell Death Differ. 2005, 12 (Suppl 1), 878–892. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre V. S.; Marozsan A. J.; Albright J. L.; Collins K. R.; Hartley O.; Offord R. E.; Quinones-Mateu M. E.; Arts E. J. Variable sensitivity of CCR5-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates to inhibition by RANTES analogs. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 4868–4876. 10.1128/JVI.74.10.4868-4876.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happel C.; Steele A. D.; Finley M. J.; Kutzler M. A.; Rogers T. J. DAMGO-induced expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors: the role of TGF-beta1. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2008, 83, 956–963. 10.1189/jlb.1007685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele A. D.; Henderson E. E.; Rogers T. J. Mu-opioid modulation of HIV-1 coreceptor expression and HIV-1 replication. Virology 2003, 309, 99–107. 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsadaniantz S. M.; Rivat C.; Rostene W.; Goazigo A. R.-L. Opioid and chemokine receptor crosstalk: a promising target for pain therapy?. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 69–78. 10.1038/nrn3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo I.; Chen X. H.; Xin L.; Adler M. W.; Howard O. M.; Oppenheim J. J.; Rogers T. J. Heterologous desensitization of opioid receptors by chemokines inhibits chemotaxis and enhances the perception of pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 10276–10281. 10.1073/pnas.102327699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubner H.; Schellhorn T.; Gienger M.; Schaab C.; Kaindl J.; Leeb L.; Clark T.; Moller D.; Gmeiner P. Structure-guided development of heterodimer-selective GPCR ligands. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12298. 10.1038/ncomms12298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berque-Bestel I.; Lezoualc’h F.; Jockers R. Bivalent ligands as specific pharmacological tools for G protein-coupled receptor dimers. Curr. Drug Discovery Technol. 2008, 5, 312–318. 10.2174/157016308786733591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akgun E.; Javed M. I.; Lunzer M. M.; Powers M. D.; Sham Y. Y.; Watanabe Y.; Portoghese P. S. Inhibition of Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain by Targeting a Mu Opioid Receptor/Chemokine Receptor5 Heteromer (MOR-CCR5). J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8647–8657. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnatt C. K.; Falls B. A.; Yuan Y.; Raborg T. J.; Masvekar R. R.; El-Hage N.; Selley D. E.; Nicola A. V.; Knapp P. E.; Hauser K. F.; Zhang Y. Exploration of bivalent ligands targeting putative mu opioid receptor and chemokine receptor CCR5 dimerization. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 5969–5987. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke B. A.; Kang G.; Zheng Y.; Obeng S.; Zhang H.; Selley D. E.; An J.; Zhang Y. Design and synthesis of a bivalent probe targeting the putative mu opioid receptor and chemokine receptor CXCR4 heterodimer. RSC Med. Chem. 2020, 11, 125–131. 10.1039/C9MD00433E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B. S.; Onge C. M. S.; Ma H. G.; Zhang Y.. Design of Bivalent Ligands Targeting GPCR Putative Dimers. Drug Discovery Today 2020, resubmitted after minor revision request. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese P. S. From models to molecules: Opioid receptor dimers, bivalent ligands, and selective opioid receptor probes. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 2259–2269. 10.1021/jm010158+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y.; Akgun E.; Harikumar K. G.; Hopson J.; Powers M. D.; Lunzer M. M.; Miller L. J.; Portoghese P. S. Induced association of mu opioid (MOP) and type 2 cholecystokinin (CCK2) receptors by novel bivalent ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 247–258. 10.1021/jm800174p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer S. D.; Sullivan M. A.; Hulse G. K. Sustained-release naltrexone: novel treatment for opioid dependence. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 2007, 16, 1285–1294. 10.1517/13543784.16.8.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adi Y.; Juarez-Garcia A.; Wang D.; Jowett S.; Frew E.; Day E.; Bayliss S.; Roberts T.; Burls A. Oral naltrexone as a treatment for relapse prevention in formerly opioid-dependent drug users: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol. Assess. 2007, 11, 1–85. 10.3310/hta11060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnatt C. K.; Zhang Y. Bivalent ligands targeting chemokine receptor dimerization: molecular design and functional studies. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 1606–1618. 10.2174/1568026614666140827144752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y.; Arnatt C. K.; El-Hage N.; Dever S. M.; Jacob J. C.; Selley D. E.; Hauser K. F.; Zhang Y. A Bivalent Ligand Targeting the Putative Mu Opioid Receptor and Chemokine Receptor CCR5 Heterodimers: Binding Affinity versus Functional Activities. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 847–851. 10.1039/c3md00080j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B.; Chien E. Y.; Mol C. D.; Fenalti G.; Liu W.; Katritch V.; Abagyan R.; Brooun A.; Wells P.; Bi F. C.; Hamel D. J.; Kuhn P.; Handel T. M.; Cherezov V.; Stevens R. C. Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science 2010, 330, 1066–1071. 10.1126/science.1194396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook Y.; Schmidtke K. U.; Gaube F.; Schepmann D.; Wunsch B.; Heilmann J.; Lehmann J.; Winckler T. Bivalent beta-Carbolines as Potential Multitarget Anti-Alzheimer Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 3611–3617. 10.1021/jm1000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumeyer J. L.; Zhang A.; Xiong W.; Gu X. H.; Hilbert J. E.; Knapp B. I.; Negus S. S.; Mello N. K.; Bidlack J. M. Design and synthesis of novel dimeric morphinan ligands for kappa and mu opioid receptors. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 5162–5170. 10.1021/jm030139v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akgun E.; Javed M. I.; Lunzer M. M.; Smeester B. A.; Beitz A. J.; Portoghese P. S. Ligands that interact with putative MOR-mGluR5 heteromer in mice with inflammatory pain produce potent antinociception. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 11595–11599. 10.1073/pnas.1305461110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Yekkirala A.; Tang Y.; Portoghese P. S. A bivalent ligand (KMN-21) antagonist for mu/kappa heterodimeric opioid receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 6978–6980. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manglik A.; Kruse A. C.; Kobilka T. S.; Thian F. S.; Mathiesen J. M.; Sunahara R. K.; Pardo L.; Weis W. I.; Kobilka B. K.; Granier S. Crystal structure of the micro-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature 2012, 485, 321–326. 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayre L. M.; Portoghese P. S. Stereospecific Synthesis of the 6-Alpha-Amino and 6-Beta-Amino Derivatives of Naltrexone and Oxymorphone. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 3366–3368. 10.1021/jo01304a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Earl P. L.; Doms R. W.; Moss B. Oligomeric structure of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990, 87, 648–652. 10.1073/pnas.87.2.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W. S.; Hughes S. H. HIV-1 reverse transcription. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006882. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarzotti-Kelsoe M.; Bailer R. T.; Turk E.; Lin C. L.; Bilska M.; Greene K. M.; Gao H.; Todd C. A.; Ozaki D. A.; Seaman M. S.; Mascola J. R.; Montefiori D. C. Optimization and validation of the TZM-bl assay for standardized assessments of neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1. J. Immunol. Methods 2014, 409, 131–146. 10.1016/j.jim.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilen C. B.; Tilton J. C.; Doms R. W. HIV: cell binding and entry. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006866. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto C. D.; Wyatt R.; Hernandez-Ramos N.; Sun Y.; Kwong P. D.; Hendrickson W. A.; Sodroski J. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science 1998, 280, 1949–1953. 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros J. A.; Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Neurosci. 1995, 25, 366–428. 10.1016/S1043-9471(05)80049-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brelot A.; Heveker N.; Montes M.; Alizon M. Identification of residues of CXCR4 critical for human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor and chemokine receptor activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 23736–23744. 10.1074/jbc.M000776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doranz B. J.; Orsini M. J.; Turner J. D.; Hoffman T. L.; Berson J. F.; Hoxie J. A.; Peiper S. C.; Brass L. F.; Doms R. W. Identification of CXCR4 domains that support coreceptor and chemokine receptor functions. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 2752–2761. 10.1128/JVI.73.4.2752-2761.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchanski A.; Lapidot A. Prediction of HIV-1 entry inhibitors neomycin-arginine conjugates interaction with the CD4-gp120 binding site by molecular modeling and multistep docking procedure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2007, 1768, 2107–2119. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C. J.; Li Y.; Tian S.; Wang X.; Douglas S. D.; Ho W. Z. Morphine enhances HIV infection of human blood mononuclear phagocytes through modulation of beta-chemokines and CCR5 receptor. J. Invest. Med. 2002, 50, 435–442. 10.1097/00042871-200211010-00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaserer T.; Lantero A.; Schmidhammer H.; Spetea M.; Schuster D. Mu Opioid receptor: novel antagonists and structural modeling. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21548. 10.1038/srep21548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.